On Location with Deliverance

AC’s editor ropes his way down into a 1,200' chasm to observe filming of a stark and violent tale that is a real “cliff-hanger” for cast and crew and, hopefully, will be for the audience, too.

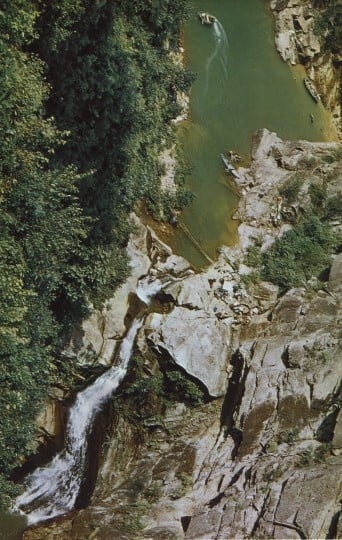

Tallulah Falls, Georgia. I’ve ended up in some odd places in my never-ending quest for interesting data to pass on to American Cinematographer readers, but the spot in which I find myself at the moment is one of the most unusual yet. At this writing, I am at the bottom of 1,200'-deep Tallulah Gorge, a magnificent chasm through which flows a river with rapids and a spectacular falls that can be turned on and off as needed — just like at Disneyland.

How I got here and what I’m doing in this place bears some explanation. It all started at the Atlanta Film Festival. As one of the finalist judges, required to sit through screenings of all the nominated films (60 hours of them this year) I was in my usual front-row-center seat in the darkened Symphony Hall blissfully watching away, when someone sat down beside me.

“Another candidate for a white cane,” I thought, absently, without taking my eyes off the screen. When the lights came up at intermission, I discovered that my front-row companion was Hollywood cinematographer Vilmos Zsigmond. Though I had met him only once before on the West Coast (when he came to visit me with his fellow Hungarian colleague, cameraman Laszlo Kovacs), I was well aware of his work, the latest of which included the photography of Red Sky at Morning, McCabe and Mrs. Miller and Peter Fonda’s The Hired Hand.

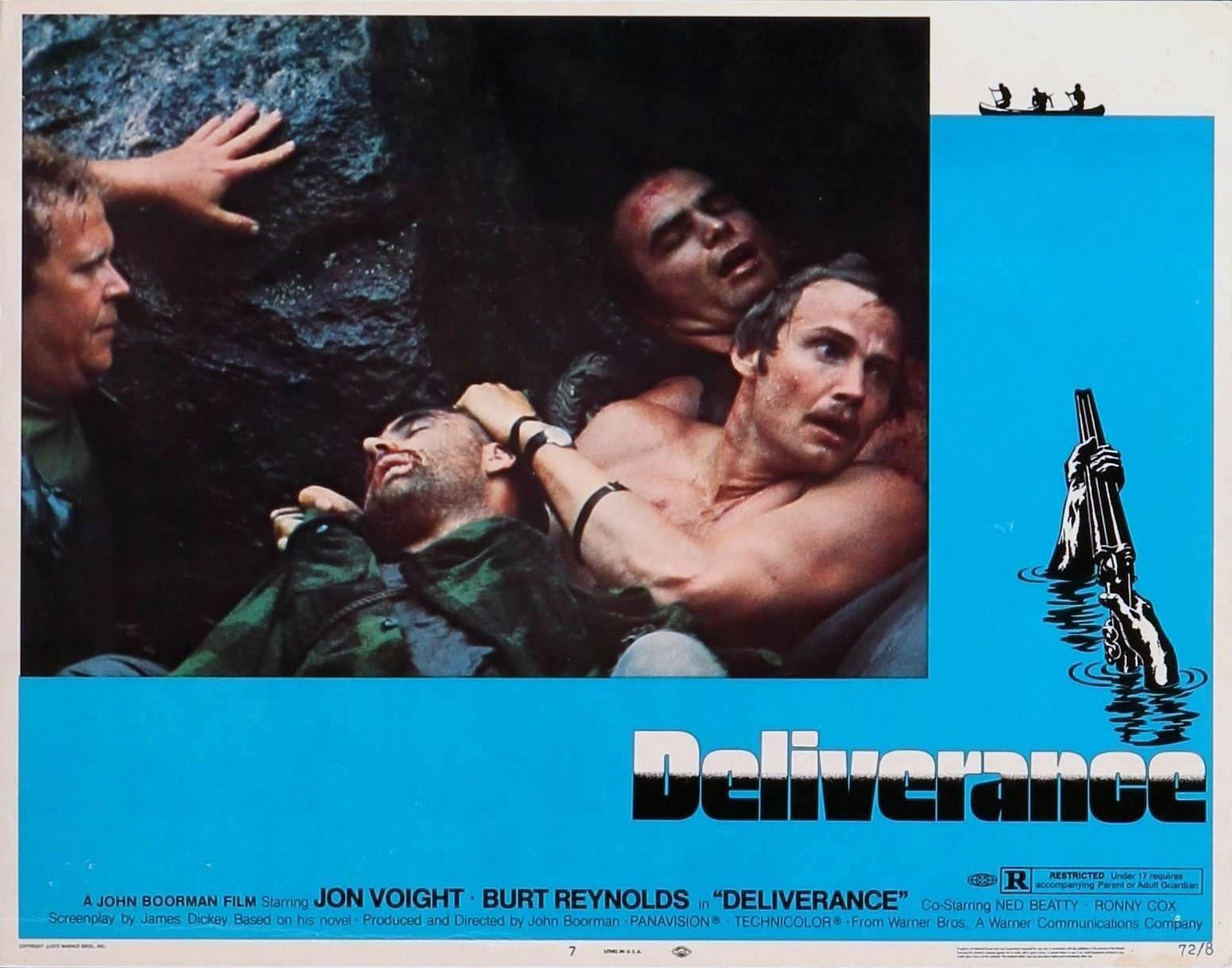

Zsigmond explained to me that he had come to Atlanta on this, his one day off from a six-day-a-week shooting schedule, primarily to invite me to visit the location site approximately 100 miles north of Atlanta where, as director of photography, he was working on the Warner Bros, production, Deliverance, adapted from the best-selling first novel by famed Atlanta poet James Dickey. The picture, starring Jon Voight and Burt Reynolds, was being produced and directed by the gutsy English director, John Boorman (Point Blank, Hell in the Pacific).

“We are trying to shoot this picture in a very realistic and modern style — which means, basically, that we want it to have a lot of contrast, but no harsh colors.”

I thanked Zsigmond for the invitation and told him I would be most happy to accept, just as soon as I had done my duty to the Atlanta Film Festival. He called me from the location a few mornings later, according to plan, and arrangements were made for Warner Bros., to send a car and driver to pick me up and take me to the location.

Arriving on schedule after I had finished an evening screening, the driver got lost five or six times trying to orbit free of the Atlanta city limits and finally headed north toward our destination. On the way I reviewed in my mind what I had learned about the story of Deliverance. It is a weird adventure yarn built around the premise that ordinary peace-loving people can sometimes, through accidents of Fate, find themselves entangled in a nightmarish situation from which there is no escape, except by means of violence or even murder.

Briefly, the storyline concerns four thirtyish solid citizens from suburbia who decide to make a canoe trip down the wild Cahulawassee River before a federal dam project, already underway, buries the river forever under a gigantic artificial lake. Along the way, two of the weekend adventurers are taken prisoner by a couple of sinister mountain types who rape one of them and kill a third member of their party. Finally, the three surviving peaceful types are forced to kill the mountain men and hide their bodies in order to escape from the nightmare that has descended upon them.

We arrive at our destination in the high back country of northern Georgia around midnight. It is a wide spot in the road called Tallulah Falls, about 10 miles from the nearest real town, Clayton. Here, in a couple of motels perched on the edge of spectacular Tallulah Gorge, are quartered the 50-odd cast and crew members of Deliverance. Zsigmond, who, as it turns out, is a night-owl type like myself, has been waiting for me and we spend the next three or four hours sipping red wine and discussing the photographic challenges inherent in a project such as this. Since the story is no Rover Boys romp, but rather a tale of terror and suspense, the main problem is to keep the photography from looking too pretty — which is not at all easy when the scenery is so beautiful.

“We are trying to shoot this picture in a very realistic and modern style — which means, basically, that we want it to have a lot of contrast, but no harsh colors,” Vilmos explains. “We thought, at first, that we might desaturate the colors and get the effect we wanted by flashing the film, just as was done on my previous assignment, McCabe & Mrs. Miller. On that picture, we used a certain percentage of flashing for each sequence, depending upon whether it was sunny or overcast. We got nice desaturated color and a certain softness, which went very well with a story that takes place around the year 1900. But the story of this picture, Deliverance, takes place today, and it has to have a completely different look, with everything sharp and contrasty. That’s why we decided not to flash the film or use any fog filters. But there was still the problem of toning down the colors.

“When you’re working on location, there is no way to control outdoor colors, so we decided to have Technicolor do the desaturation at a later time by adding an extra tint of black to the color balance. We made some tests of that method and they really look exciting. You actually have the feeling of looking at a black-and-white picture — until you see the people. Their skin tones look so realistic that I'm sure everyone will wonder how we got a black-and-white look without changing the skin color at all.

“Last week I had an interesting experience. We were going down the river when a storm came up. The sky became very overcast and it started to rain. I looked at the landscape and the water and they appeared exactly the same as in the tests we made, with Technicolor adding about 25% black to the color balance. That convinced me that we were doing the right thing with the photography of this film.”

“It’s about a man, an ordinary guy, who’s just living a quiet life until he’s thrust into a situation where he has to use emotional and physical resources that he didn’t even know he possessed.”

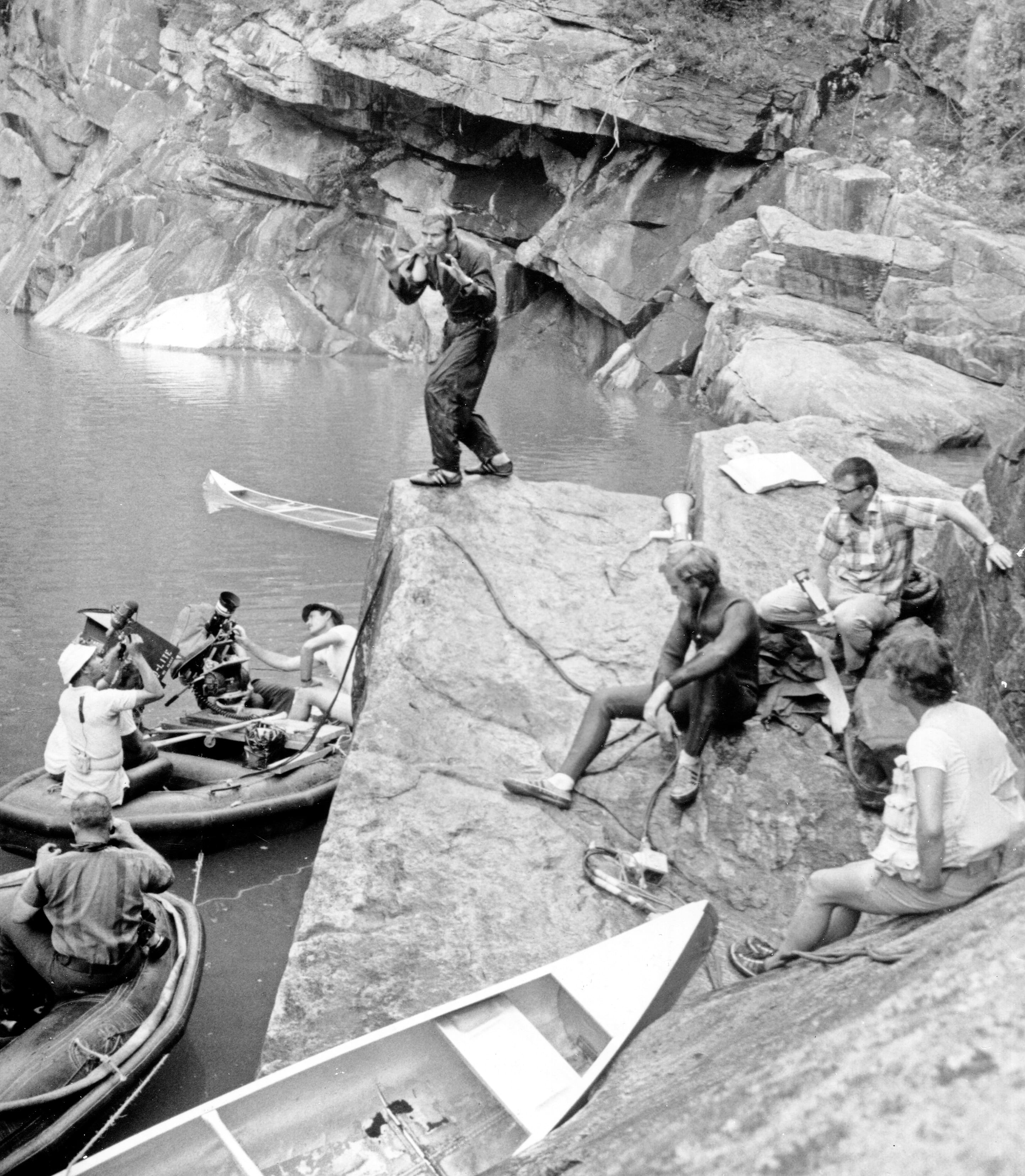

The next morning — crack of dawn, and all that — we make our way to the edge of the gorge, which is practically right outside the door. The only way to get to the bottom, where the company is shooting, is to rope your way down a 1,200' almost-vertical cliff. I wouldn't mind tackling it on skis, if the slope were snow-covered, but it's simply very muddy and I have visions of losing my grip on the rope and ending up as a mud-pie at the bottom. What the hell — you only die once!

The descent is as hairy as it promised to be, but with much slipping and sliding and involuntary pirouettes around the rope, I make it to the bottom. I pity the cast and crew members who have to do this act twice a day, but I'm informed that they have been selected as much for their physical agility as for technical skill. Even so, there have been accidents, though no fatalities as yet.

Once on terra firma, Vilmos introduces me to director John Boorman, who welcomes me aboard with warm cordiality. “Vilmos and I spent a lot of time beforehand planning the picture and trying to give it an individual look of its own, which would help tell the story,” he tells me. “I’ve always tried to get a color unity into my pictures and Vilmos and I spent a lot of time visiting locations and discussing how we could do this. He was full of very marvelous ideas and we eventually decided to keep everything black and green, using a lot of contrast, and this is what we’ve done. It's a problem for Vilmos, because I'm asking him to get a really very stylish look, while shooting under conditions in which it's extremely difficult to impose style upon the environment. We have so many sequences that must be shot where you really can't get much equipment into the area, but somehow he manages to get the effect. I feel that through working with xenon lights and crystal-sync motors and the fast film stock and so on, we've been able to get footage that would have been impossible to get two or three years ago.

“We did one whole 10-minute sequence in the deep woods on an overcast day. It was shot almost entirely with the Panavision 55mm lens wide open at F/1.4, and the effect was marvelous. It had a very, very strange feeling — which is what we were after. This is a very strange and fierce and violent story, and we want to give the whole film the feeling of being somewhat in another world — the world of a dream, a nightmare. That’s really, fundamentally, what it is — but it's also a kind of initiation story. It’s about a man, an ordinary guy, who’s just living a quiet life until he’s thrust into a situation where he has to use emotional and physical resources that he didn't even know he possessed. And so, the river is very representative in the story, symbolizing the deep underground flow of the unconscious. That’s why we want to get this dark strange feeling into it.”

Boorman excuses himself to supervise the next set-up and I'm introduced to the stars of this dark drama, Jon Voight and Burt Reynolds. They are a very rugged pair of lads — and need to be because, I'm told, they're doing most of their own stunts in this picture.

“I slid down a 40' waterfall the other day,” Reynolds tells me. “It looked simple enough, but I lit right on my tailbone, on a submerged rock, and bounced about five feet in the air. Man, did that hurt. I could hardly move for several hours afterward.”

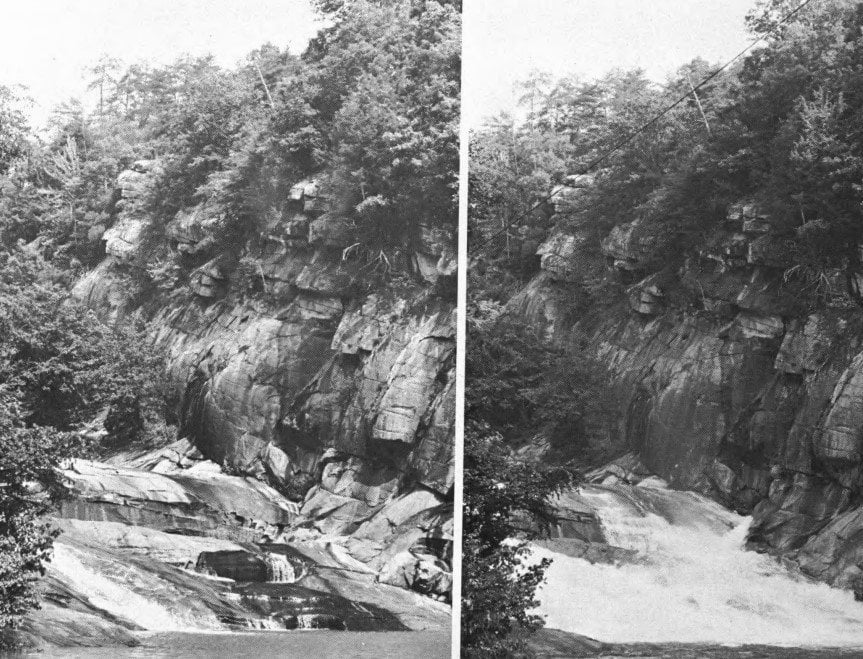

The river just now looks very tame indeed, a veritable pussycat of a waterway, but I'm told that's because it's been dammed upstream to provide hydroelectric power. The authorities, however, are extremely cooperative and will open the dam whenever turbulence is needed for the cameras.

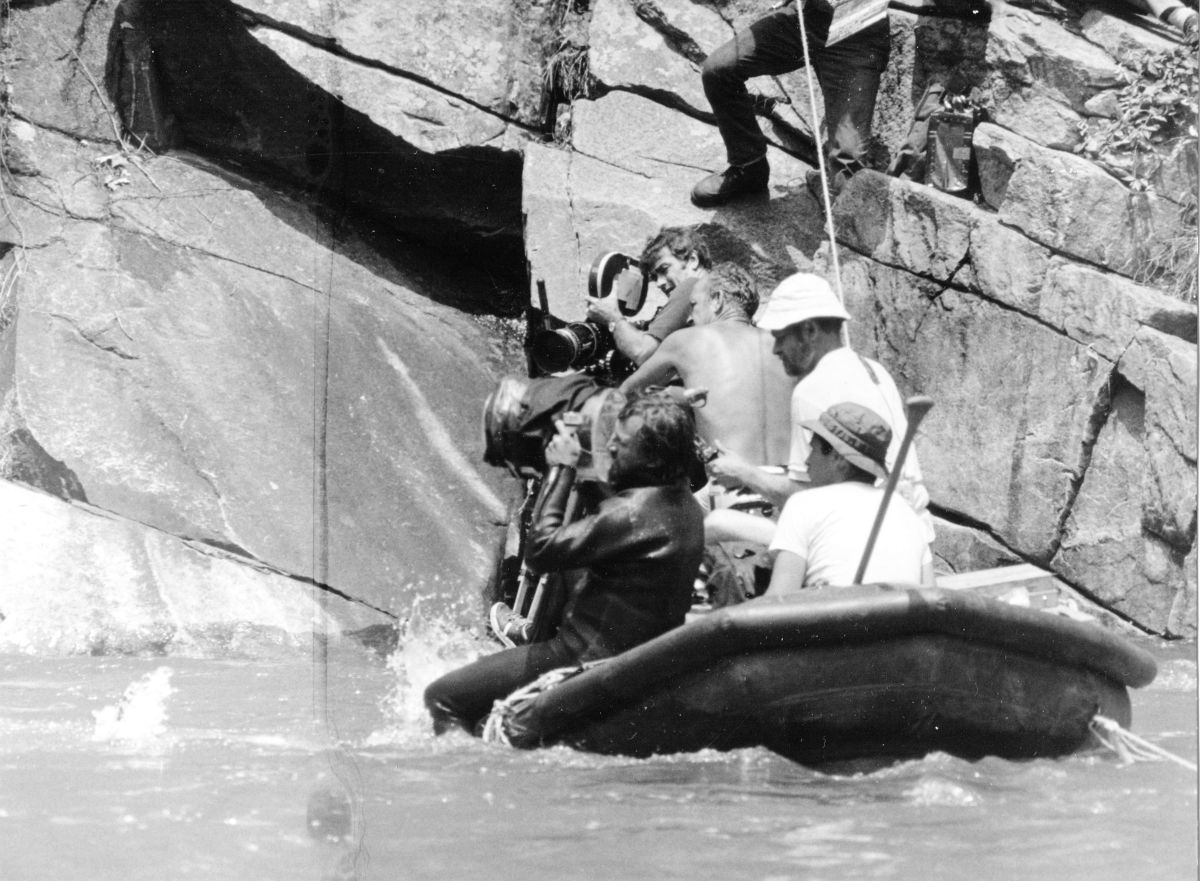

I get a chance to see this effect in action very shortly. Vilmos and his crew are now in wet suits and have the camera mounted on a rubber boat. The scene calls for Voight to dive into the raging river in a frantic effort to locate one of the foursome who is missing.

When everything is in readiness, an assistant contacts the people at the dam by radio. “Okay, let ’er rip!” he bawls. About five minutes later a torrent of white water comes roaring down the gorge, bursting over cataracts, churning into rapids and filling out the waterfall quite impressively. Neat! Voight dives into the boiling rapids and does his thing, while the rubber boat, with camera crew and director aboard, struggles to keep him zeroed in with the lens. After several takes, including a few for which the camera is submerged just below the water level in an open-topped glass box, the scene is in the can. Voight clambers onto the shore, wriggles out of his sodden jumpsuit, and sits shivering on the bank in his long-johns. The assistant bawls, “Turn ’er off!” and soon the river is flowing gently again, like sweet Afton.

been dammed upstream. But when a dam is opened for filming a scene, the Gorge begins to

boil with a torrent of raging white water. Dam authorities obligingly turned water on and off as

needed during the shooting.

But it isn’t that way in other sections where the dams don’t contain the water. “This is a very wild river,” Boorman tells me. “The most difficult stuff we’ve done so far has been the canoeing sequences in rough water. We’ve worked out a system where we put six or seven people and the equipment in rubber boats. The actors are in canoes, and we just go down river until we find a place where we want to shoot. We film everything with dialogue and it’s rather special, because you see the principals going down really fast water. They’ve all learned canoeing to an extent where they are capable of taking hazards, and they can ride through anything that an open canoe can navigate. They’re going through stuff which even very good, highly experienced canoeists wouldn’t try. And, of course, we have to go through it, too. It's hazardous and very trying, and you don’t have the luxury of an expeditor around to help you out.”

Lunch is called, and that turns out to be a production,too. There’s no such thing as a commissary truck in these here parts. The food, prepared by loving hands in local kitchens, is trucked to the edge of the gorge. Getting it down to the hungry cast and crew is something else again. It has to be lowered by means of a jerry-rigged system of cables and pulleys. Then the trick is to find a place among the rocks to set up a buffet, where there is no level land. The next question is, where do you perch to eat your lunch? You pick out a rock and squat down on it with the plate in your lap, hoping you won’t end up with a crotchful of hot country gravy and grits. It’s a good thing I used to be a Boy Scout.

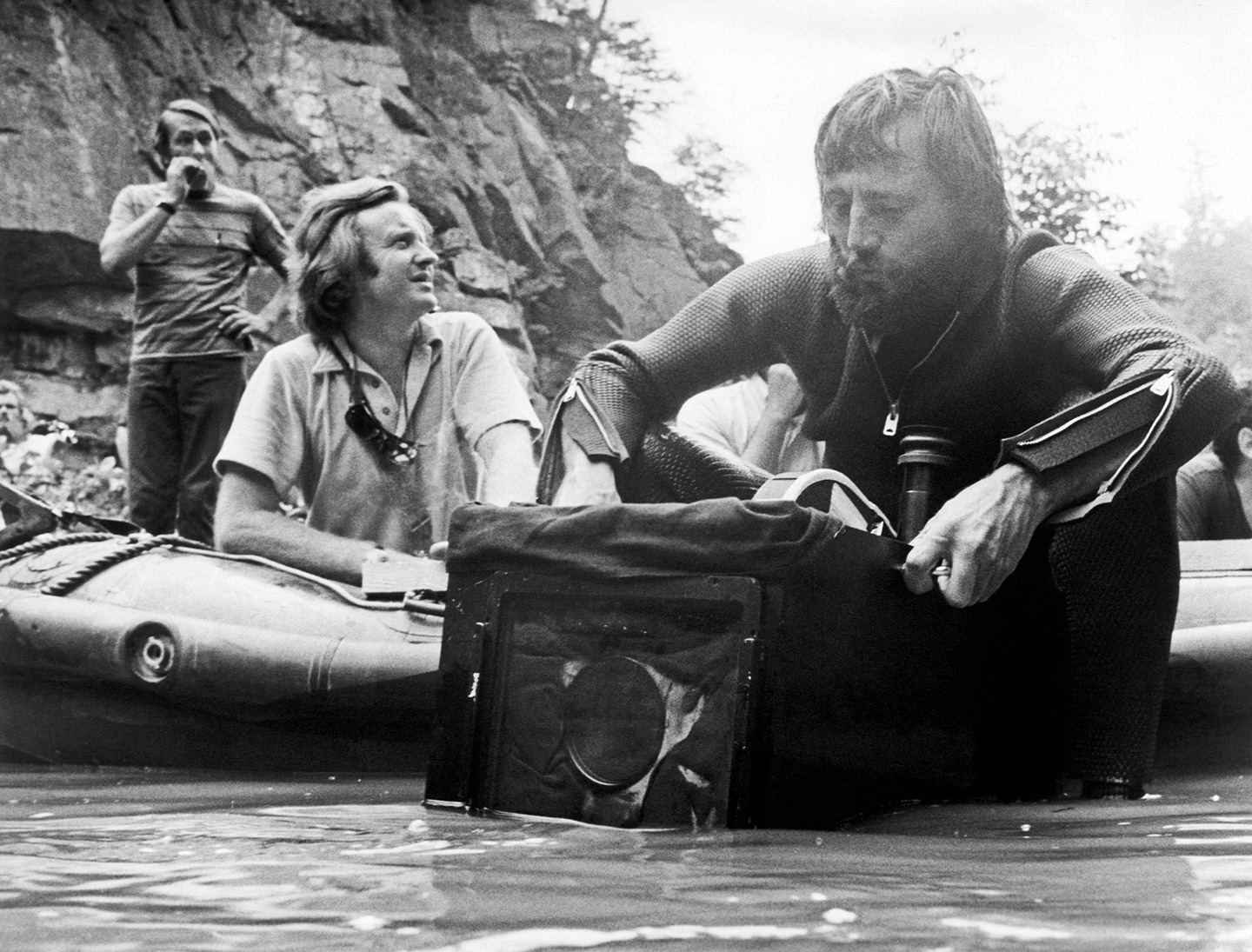

Vilmos, still in his wet suit, pulls up a rock and joins me for lunch. Despite the fact that he’s had only about three hours of sleep (How well I know!) and has been clambering about the rocks like a mountain goat all morning, he is bright-eyed, bushy-tailed and rarin’ to go.

“I like working with John Boorman very much, because he depends on everybody in the cast and in the crew,” he tells me. “John wants everybody to work very hard at his job, but, on the other hand, he’s like an orchestra conductor who brings the best out of everybody.

“John knows a lot about photography, which makes it very easy for me to work on this picture. He knows, for example, that a scene shot on an overcast day cannot match a shot that was filmed on a sunny day. You can match closeups easily enough, but not long shots. It's really fantastic to work with John because he understands this. It’s very interesting to realize how much English directors know about weather. It’s probably because they have more problems of that kind in making their pictures than we do in California. They really have to struggle sometimes to get that look of visual continuity into their films. Other directors don’t seem to have the same feeling for continuity of weather. They want you to shoot if it's sunny or overcast, or even if it’s raining. I think this is wrong, because there are certain things you just can't do in matching light.”

After lunch, it's up and at ’em again. They’re shooting scenes now in which Burt Reynolds, supposedly disabled with a broken leg, is lying on a rock ledge next to the water, while Voight prepares to scale the cliff. Reynolds likes this because he gets to rest his sore tailbone.

In order to get the effect of water ripples reflecting onto his face, a Xenotech Sunbrute lamp is beamed into a shallow pan of water, on the bottom of which are shards of broken mirror. When the water is agitated slightly, the reflection is most realistic. This is an old cinematic trick, but I've never seen it done with a xenon arc before.

“These xenon arcs are really helping us a lot,” Vilmos observes. “It’s a light-weight unit that one man can handle easily — even holding it while standing in the water. We brought them along, basically, because I knew we wouldn't be able to use Brute arcs on this show. Even if we had twenty more electricians we couldn't use the Brutes, because it's very hard to get them into position. Even the lighter Brutes are too heavy for us — and, of course, you couldn’t put them into the water. It would be impossible.”

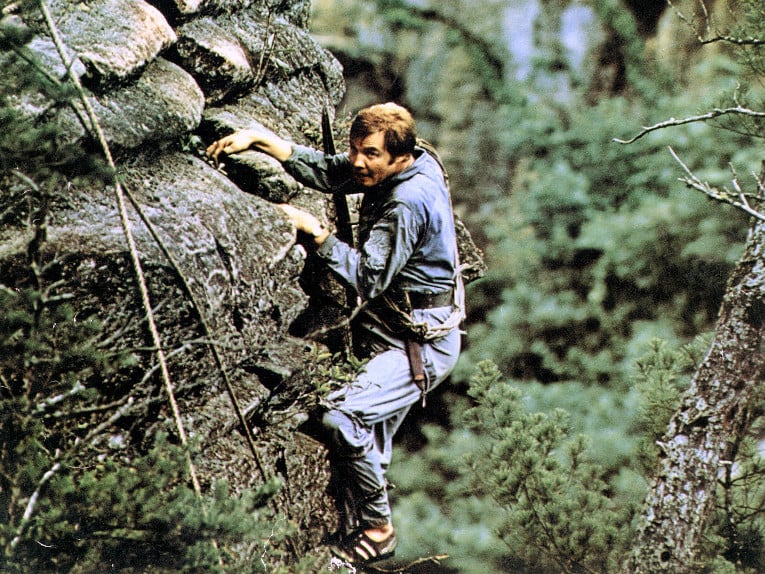

The next sequence concentrates on Voight climbing the cliff. Though there is a stunt double available, he elects to do it himself — which will be a hairy adventure, because this is a vertical rock precipice about 200' high, with hand-holds few and far between. The camera, on a tripod, is set up on a rock ledge that can’t be more than 18" wide and Vilmos clambers up to operate it himself.

The shot is made without incident and the crew shifts things around for the next setup. It would be hard to describe just how difficult this is to do on terrain where there is hardly a square foot of level ground. It’s a kind of grim ballet, scaling wet rocks and trying to keep from falling into the river, while stepping gingerly around the cables which seem to be stretched everywhere.

“Working in this gorge is pretty tough,” Boorman concedes. “The rocks are treacherous and slippery and people are falling all the time and bruising themselves. We’ve been very lucky not to have anything more serious. The actors and crew are in and out of the water continually. They’re wet all day long. I don’t remember when my feet were dry last. When you take your shoes off at night, you see this sort of soft, white, rough skin. Then you wake up in the morning and your shoes are still wet — so you grit your teeth and put them on again, and you put on your wet suit, which is cold, and you shiver for a little while. Then you come down to the water, and as soon as you’ve made that first plunge in, you’re into another day and you don't think about it anymore.

“But the crew we've got is handpicked and is made up of types that like this kind of thing. They love it. They’re a terrific bunch — always in the water, helping out with the shots. We've really got a very good spirit.”

Inevitably, the time comes when I must leave this rocky paradise. The question arises as to how I'm going to be able to do that hand-over-hand scene up 1,200' of rope, while carrying my 45 pounds of cameras, recorders, etc. Someone suggests that I send it up on the Rube Goldberg pulley-and-cable goodie, but I’ve just dropped my Hasselblad on the rocks (something now rattles around inside and I can’t see anything through the viewfinder), so I’m a little bit wary of that scheme.

“It’s fairly safe,” I’m told, “even though we did lose a Panavision zoom lens off of it the other day. It fell into the drink — but there’s nothing wrong with it that a couple of thousand dollars worth of repairs can’t make right.”

Reassuring!

In the end, I decide to risk the equipment on the cable thing, rather than buck for a heart attack while hauling all that gear by hand.

Up on top, the driver is waiting to take me back to Atlanta — back to civilization, with its crowded freeways, hints of smog, and overpowering skyscrapers. Somehow, compared to all this natural magnificence, it doesn’t seem too appealing.

I take one last look down from the rim of Tallulah Gorge. Far below I can see the cast and crew of Deliverance getting ready for the next setup along the river. They look like ants — very busy ants. But happy ones.

Zsigmond would later be invited to join the ASC, and go on to photograph numerous films including The Long Goodbye, Scarecrow, The Sugarland Express, Close Encounters of the Third Kind, Heaven's Gate and The Deer Hunter.