Panavision at 70

A focus on the filmmaker continues to drive innovation and evolution at the industry stalwart.

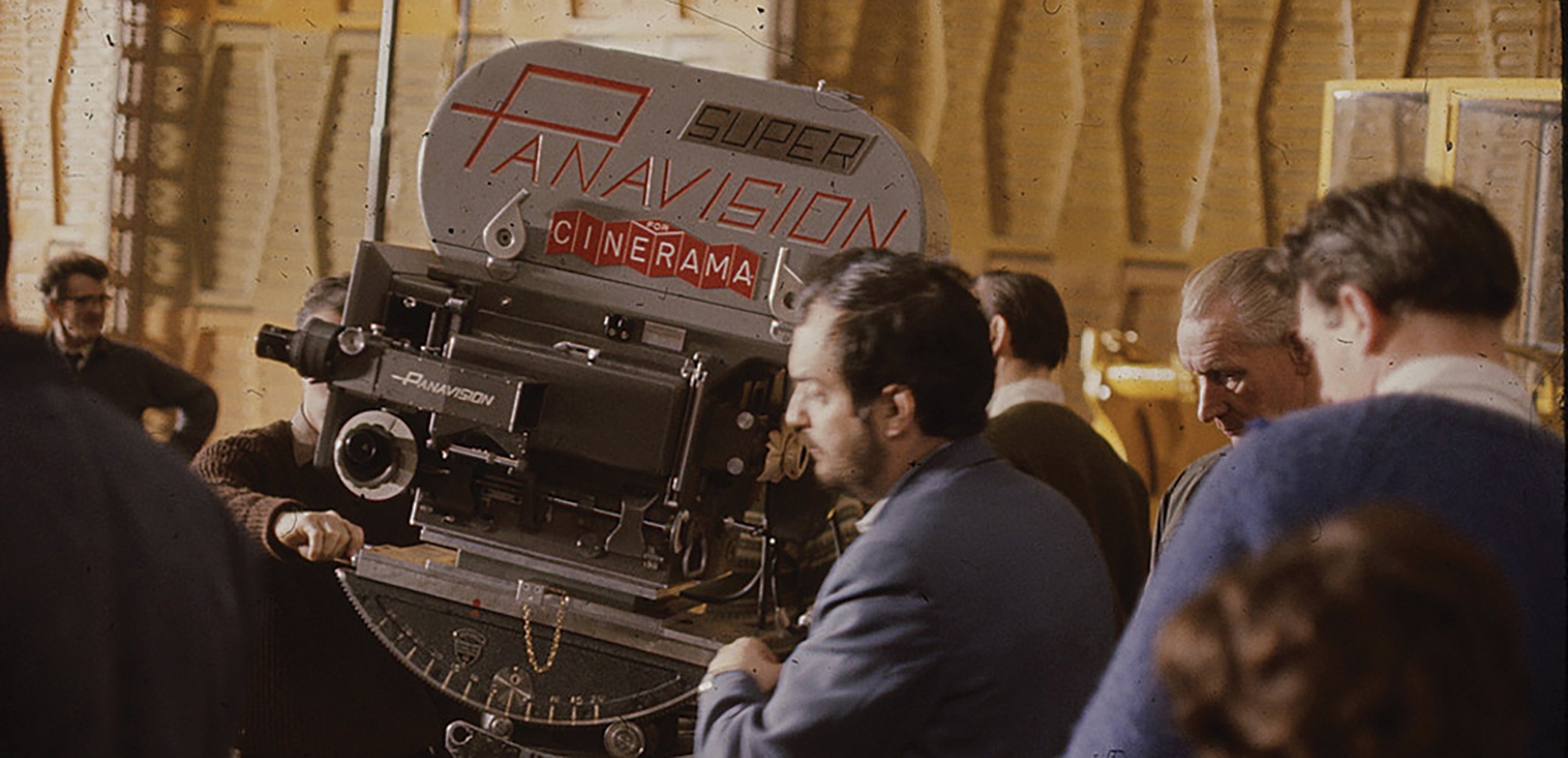

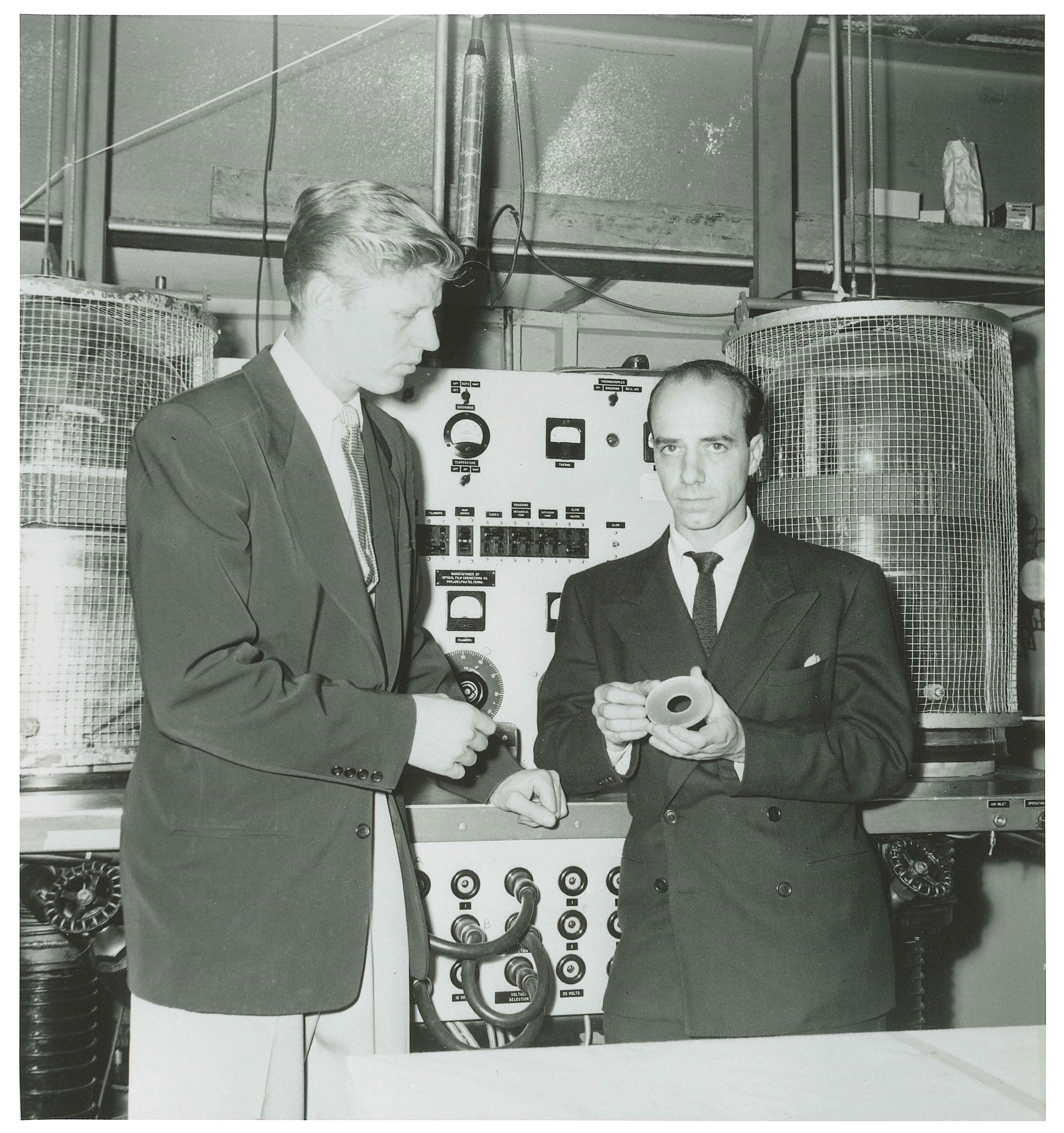

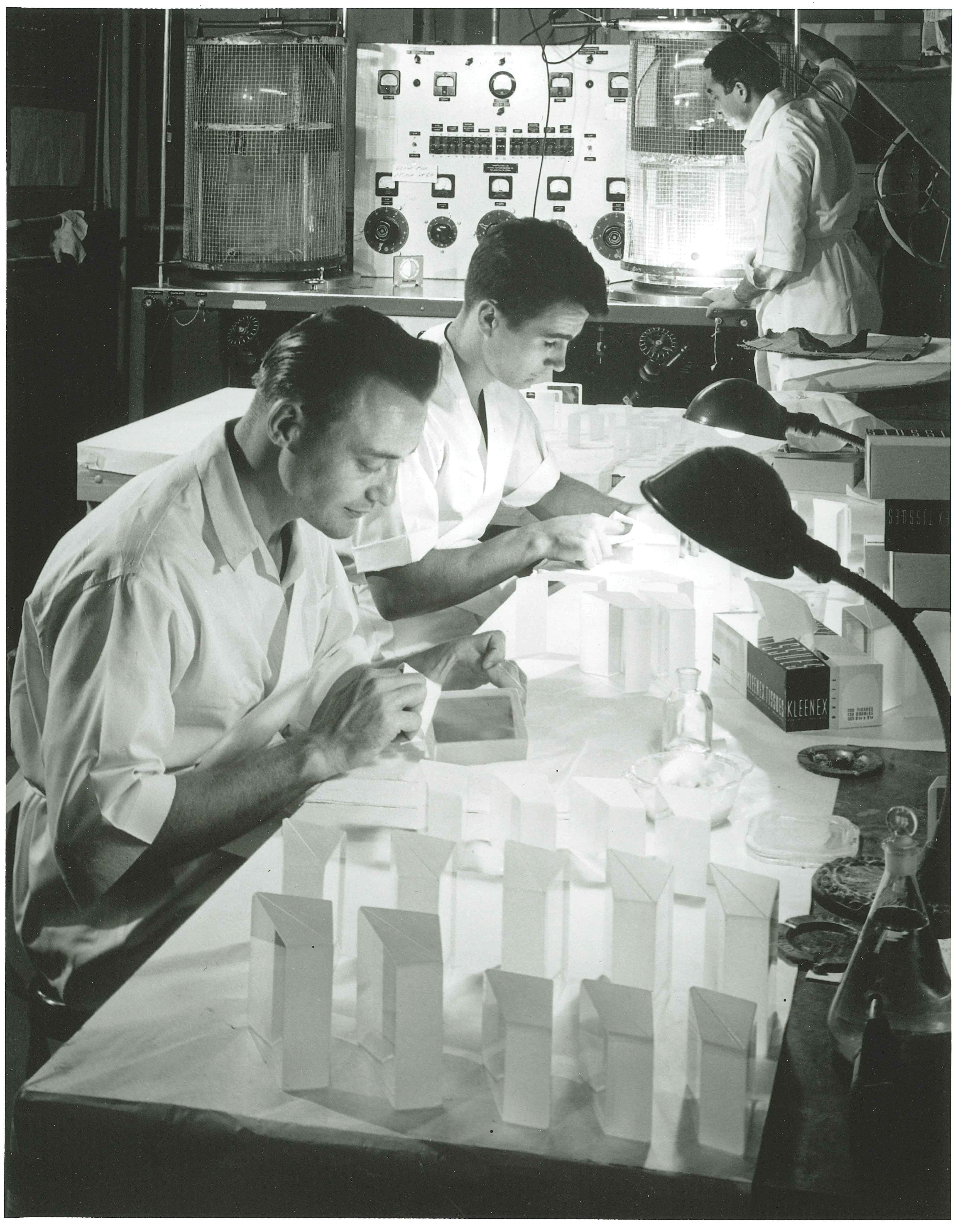

Panavision was founded on Feb. 18, 1954, by Robert Gottschalk and Richard Moore, along with William Mann, Walter Wallin, Meredith Nicholson and Harry Eller, and the company’s name has since become synonymous with motion-picture production around the world. Its first goal was to design and manufacture anamorphic projection lenses for the then-new CinemaScope format. Its first offering, the Super Panatar, was introduced the following month.

In recognition of Panavision’s 70th anniversary, AC recently spoke with four executives at the company’s headquarters in Woodland Hills, California, to get their take on the company’s current strategy and vision for the future: president and CEO Kim Snyder, COO Michael George, senior vice president of client relations and business development David Dodson and senior vice president of optical engineering and lens strategy Dan Sasaki. All are associate members of the ASC.

American Cinematographer: Kim, let’s start with you. Where do you see Panavision heading?

Kim Snyder: Panavision has long been dedicated to bringing tools to the industry for our customers — namely, cinematographers — and when I think about the future, I certainly see that continuing. There’s a lot of evolution with respect to technology that’s changing the way we make movies. Our objective is to invest in innovation focused on technology so that we can provide a wide [array] of toolsets for filmmakers to deliver their creative intent. That’s the foundation of what we do, and that underpins the brand, along with our focus on customer service and a global footprint.

We’re now focusing our efforts across the imaging chain more than we have done historically. We invested in postproduction with Light Iron, but our intent is not to replicate the big post houses, which do a great job, but rather to have a post-services business of scale. That allows us to think about what tools we could bring to bear from a services perspective that will complement the equipment, tools and services we [already] provide. It’s about bringing post closer to production. Our key strategic pillar is optics. We’ve always invested in that space, and we will continue to do so. It’s not our intent to become a camera manufacturer again.

Our focus is on optics and accessories that will improve the experience on set. We’re investing in software and services to optimize the point of capture and how you manage that image asset.

Dan Sasaki: The biggest change now is that we’re no longer just supplying a lens — we’re integrating with both previs and post. Many shows now are heavily visual-effects driven, so we’re working in collaboration with those teams as well. We’re speaking to the previs teams; we’re speaking to the visual-effects teams; we’re speaking to the colorist who’s developing the LUT. We’re finding out that we can’t stay isolated in our own silo anymore. Everything has to come together — especially on visual-effects-heavy shows where they’re asking for very stylized lenses, because if we make it too stylized, then the visual-effects companies likely underbid their abilities to match the lenses. So, it’s become a very collaborative process. There’s so much power in post that affects the image and the lens. We’re asking the colorists: How much of this is going to be HDR? How much are you going to process? Are you going to crush the blacks? All of that makes a difference in the quality we provide the cinematographer in the lens.

Snyder: We often say we’d like to be a provider of equipment and services on an end-to-end basis. That doesn’t mean we’re going to touch every single thing that happens in the workflow, but we’re going to pick the ones that are relevant to capture and then collaborate early. We feel we can position our customers to be more successful and efficient in achieving their aesthetic if we do that kind of collaboration upfront. In the meantime, we’re going to continue innovations in the core of optics, spherical and anamorphic.

Sasaki: The inception of anamorphic was kind of ‘the poor man’s 70mm.’ The 2x anamorphic squeeze was designed to maximize the area of the 35mm frame. Now, we have this fluidity anywhere from Imax down to Super 16 and no hard-fast standards anymore. Streamer producers want maximum visual acuity or resolution. You don’t necessarily get that with spherical. By changing the squeeze ratio to fit the commonality of the native capture format, we can maximize resolution plus give you the artistic artifacts. It’s an ever-evolving world. With optics, we’ve seen more innovation in the last two years than I’ve seen in my entire life. We’ve got to keep up with technological advancements of production as well.

An example of that is the work you did on Avatar: The Last Airbender, customizing lenses to reduce LED-wall moiré.

Sasaki: Exactly. What we learned with [executive producer/producing director/cinematographer] Michael Goi [ASC, ISC] is something that can be applied to any show. Michael came in here and asked how we could get rid of the moiré, so we brought a wall in here, studied it, learned the sampling error and figured it out.

Michael George: That’s a great example of Panavision as the filmmaker’s partner. Now, we can incorporate that same remedy into future optics as well. We rise to the occasion and try to figure out how to support filmmakers the best we can. It’s been an interesting journey, and technology has evolved so rapidly over the past 10 years. During the pandemic, when everyone had to be isolated in zones [on set], we developed the Wi-Fiber system that allowed video village to be 1,000 feet away. That was a game-changer, too.

David Dodson: When we get asked to do something, we put the engineers to work. The team gets really excited about it. For Quentin Tarantino and Robert Richardson [ASC] on The Hateful Eight, Quentin wanted to shoot a 15- or 16-minute take on 65mm without cutting. No one had ever made a 65mm film magazine that big, but it was important for Quentin, so we took on the rather monumental task of making that happen. It wasn’t just making a larger magazine, it was also making sure the motors could handle the torque of all that film and not be a greater draw on power, and so many other factors. But we put the R&D into it and made it happen.

Snyder: We also feel a responsibility to nurture young and underserved filmmakers, those who perhaps have had limitations in terms of being able to succeed. Some characterize us as a luxury brand, but we’re accessible to everyone.

Dodson: We also have the New Filmmaker Program. And we’ve had such a good time meeting a lot of directors.

Sasaki: Directors often feel there’s this ‘black art’ mystery in cinematography that they don’t fully understand, and when they come in and see the actual process, they feel a bit more involved with the whole imaging part of it. We’ve noticed it really pays off; the director is more freely explaining what they want, and it becomes much more collaborative with the cinematographer.

Some of the directors and new students that come in have never been told, ‘No, that can’t be done.’ So, they’re asking us for ideas we’ve never even thought of! They may not know that you can’t make a lens faster than an f/0.5, so they ask, ‘Can I go faster?’ And that inspires us to come up with a possible solution.

[When approached recently for a wide anamorphic lens that could focus close,] I said, ‘We can do that.’ So, we gave them a 29mm that focused down to a half inch from the front element. Because of that, we’ve developed a new technique in anamorphics that integrates a secondary method of focus that brings the lenses closer without making the faces look bad. That’s where innovation comes from: requests from the artists. We’re inspired by these customers.

How does the company’s emphasis on optical innovation impact your day-to-day, Dan?

Sasaki: Well, it’s not just me. I’m like the chef, but there are a lot of other great professionals in the kitchen. I’ve got great teams. Right now, we have 12 lenses being built that have to be shipped out by tomorrow. So, I have three people in my office working, four in service and I’m borrowing people from manufacturing. I’m relying on who’s best at what. All of Panavision is a huge team.

Snyder: Dan has an extremely talented team, and we work hard to try to add to it as much as we can. It sounds obvious, but it’s about talent and skills, passion and commitment. These people will not leave until it’s done. This company is full of people that love the industry and their customers so much.

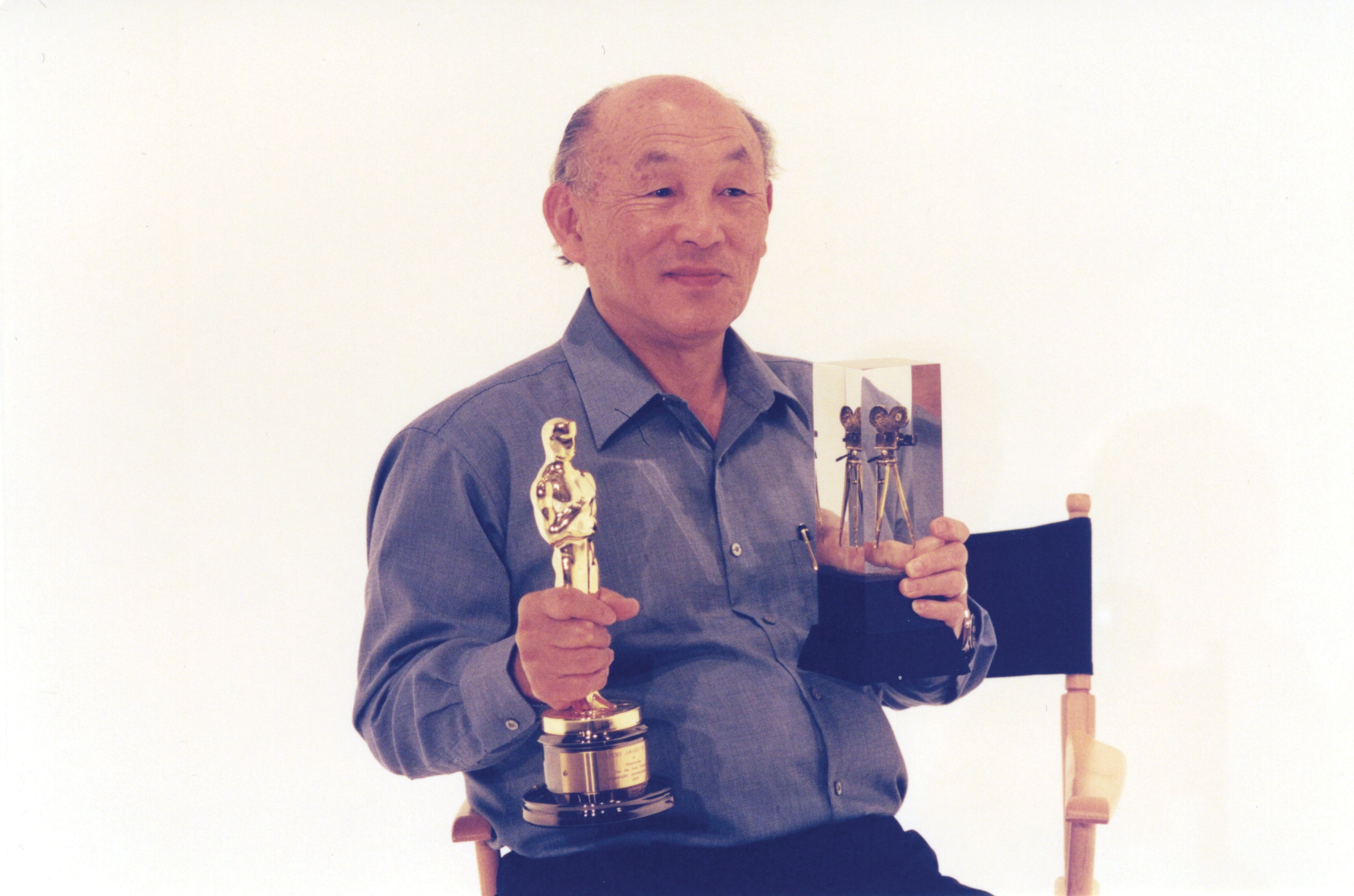

Sasaki: We’re built on good roots. Look at [former senior vice president of engineering] Tak [Miyagishima] and [former vice president of optics] George [Kraemer] and my dad [former vice president of operations Ralph Sasaki] — these are the guys who taught me. Right now, ‘special optics’ is a hot term, but it’s what this company has always done, going back to the Lawrence of Arabia [‘mirage’] lens George Kraemer made. Optics has always defined Panavision and how we serve this community.

Some might be surprised to learn that you don’t charge the customer for the R&D you put into special products — you just rent the result.

Snyder: Absolutely. I think that’s part of our differentiation.

George: It’s those challenges that really bring out the innovation. And once that product is introduced into the market, there’s this awareness that it exists, and that drives more business. So, the value proposition is word of mouth, and every new innovation goes into inventory for the next filmmaker to use. Then we look back, and we’ve built an impressive precision tool that serves the industry and helps creatives achieve their vision. That’s what Panavision is about.

Snyder: And that’s what we’ll keep doing