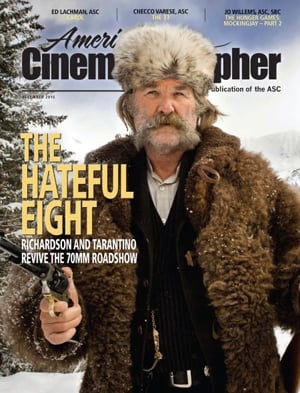

Wide Wide West: The Hateful Eight

Robert Richardson, ASC helps Quentin Tarantino revive, shoot and present a classic 70mm format for this Western tale.

Quentin Tarantino’s crew is reconfiguring the set of Minnie’s Haberdashery, which has been transferred from a location in Colorado to a bone-cold soundstage at Red Studios Hollywood — artificially chilled to 30° Fahrenheit and 80% humidity to make the cast’s exhaled breaths visible. Snug in a parka that’s been pinned with a sheriff’s badge, the director cheerfully greets visitors from American Cinematographer to the set of The Hateful Eight with a hearty, “Welcome to our super film set!”

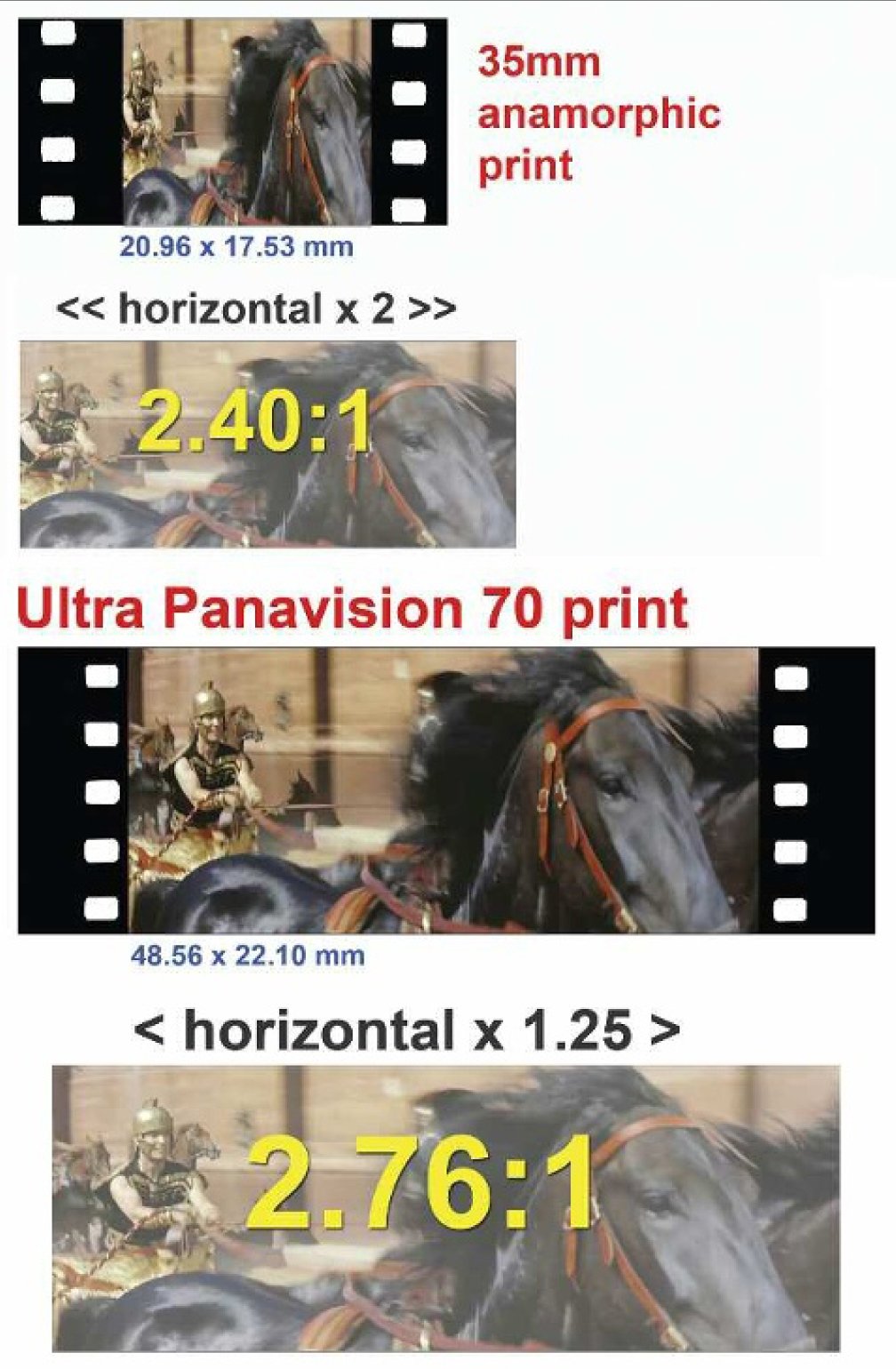

He and cinematographer Robert Richardson, ASC proceed to discuss how their team managed to pull off shooting the entire movie in a widescreen film format not used in almost 50 years. The director refers to Ultra Panavision 70, with its 2.76:1 aspect ratio, as “the widest format there is, outside of three-screen Cinerama.”

As Tarantino explains, he fell madly in love with Ultra Panavision 70, which during its heyday was responsible for giving the world just 10 features, including Ben-Hur and Mutiny on the Bounty. The last Ultra Panavision 70 feature, Khartoum, debuted in 1966, when the more financially feasible anamorphic 35mm had already entered the fray. Richardson adds that the format works beautifully for intimate close-ups, and lauds its ability to capture the “landscape” of the human face.

Cameras soon roll as Samuel L. Jackson’s character, Major Marquis Warren, sets upon Bruce Dern’s General Sandy Smithers with a slow-burn, progressively indecorous monologue, during which Warren takes great relish in telling Sanders a sadistic story that’s certain to provoke the older man.

Some weeks later, as the movie nears completion, Tarantino, Richardson and a handful of their colleagues discuss their Hateful Eight adventures in more detail. The film is Tarantino’s second Western, following Django Unchained (AC Jan. ’13); the plot concerns eight strangers holed up in a cabin in the Colorado mountains in the middle of a blinding snowstorm, with hate, revenge and betrayal on their minds. The movie’s launch is being produced, packaged and sold as a “roadshow” event, beginning its life exclusively as a 70mm film presentation — including a program, musical overture and intermission — in a special two-week engagement limited to approximately 100 theaters. The plan is designed “to hearken back to the romantic days of cinema,” explains producer Shannon McIntosh.

“I thought maybe I could shoot it in a format that would demand that they release it on film. If [the studio] is going to spend the money to shoot on 70mm, they’d want some sort of bang for their buck.”

— Quentin Tarantino

A digital-cinema version, slightly shorter in length and without all the bells and whistles, will subsequently go out in wide release to the rest of the world, but Tarantino’s virtually singular goal from day one has been to make a splash with a high-profile, large-format, projected-film extravaganza. Foreseeing the inevitable uphill battle for studio approval, he sold the large-format idea to the Weinstein Co. based on the notion that while exhibiting the movie might be a complicated and costly affair — involving the retrofitting of 100 or so digital theaters across the country — he could make the movie good enough and cost-efficient enough that “we could end up [recouping] a third of our budget and paying for the operating expenses in just two weeks in 100 theaters.”

“I thought maybe I could shoot it in a format that would demand that they release it on film,” Tarantino continues. “If [the studio] is going to spend the money to shoot on 70mm, they’d want some sort of bang for their buck. So I figured we’d propose the big roadshow thing and see where we were after that. But then, the weird part was that I felt maybe we could show that 70mm wasn’t a lost cause. The excitement of the whole thing is that we might have accidentally bumped into a really good idea — the saving of film [for a theatrical exhibition].”

Assuming they would shoot 70mm in the spherical format, Tarantino and Richardson asked Panavision to show them various options. Fate intervened last summer, however, when Richardson and his 1st AC, Gregor Tavenner, met with the company’s vice president of optical engineering and lens strategy, ASC associate Dan Sasaki, and made a discovery that turned the project on its ear. Deep in the bowels of Panavision’s headquarters in Woodland Hills, Calif., Richardson discovered a shelf of what he calls “some very unusual-looking lenses,” which turned out to be the original long-forgotten Ultra Panavision 70s. They had not been used in decades. The cinematographer was instantly enamored.

“That’s when the avalanche started,” Sasaki says. At Richardson’s request, Sasaki clamped one of the old heavy lenses to his projection bench and imaged it at 10’. As Sasaki recalls, “Bob’s and Gregor’s eyes went when they looked at the nice warmth and the organic roll-off”

“I made the decision then,” Richardson says. He makes it clear, however, that the initial undertaking was in essence a feasibility study as he continued to develop a spherical backup plan. Success in rejuvenating the Ultras was far from guaranteed.

A protocol was arranged whereby Sasaki’s team would restore enough of the lenes for Richardson to go to Colorado and test them. If Richardson felt comfortable with the results, he would show the footage to Tarantino. As it happened, the cinematographer was more than pleased; he was ecstatic. And so, with the assurances from Panavision that they could make the lenses work with morern Panaflex System 65 Studio and High-Speed Spinning Mirror Reflex cameras, and Tavernner’s confidence that he could pull focus with the optics, the filmmakers committed themselves to producing the 11th Ultra Panavision 70 movie — the first since 1966.

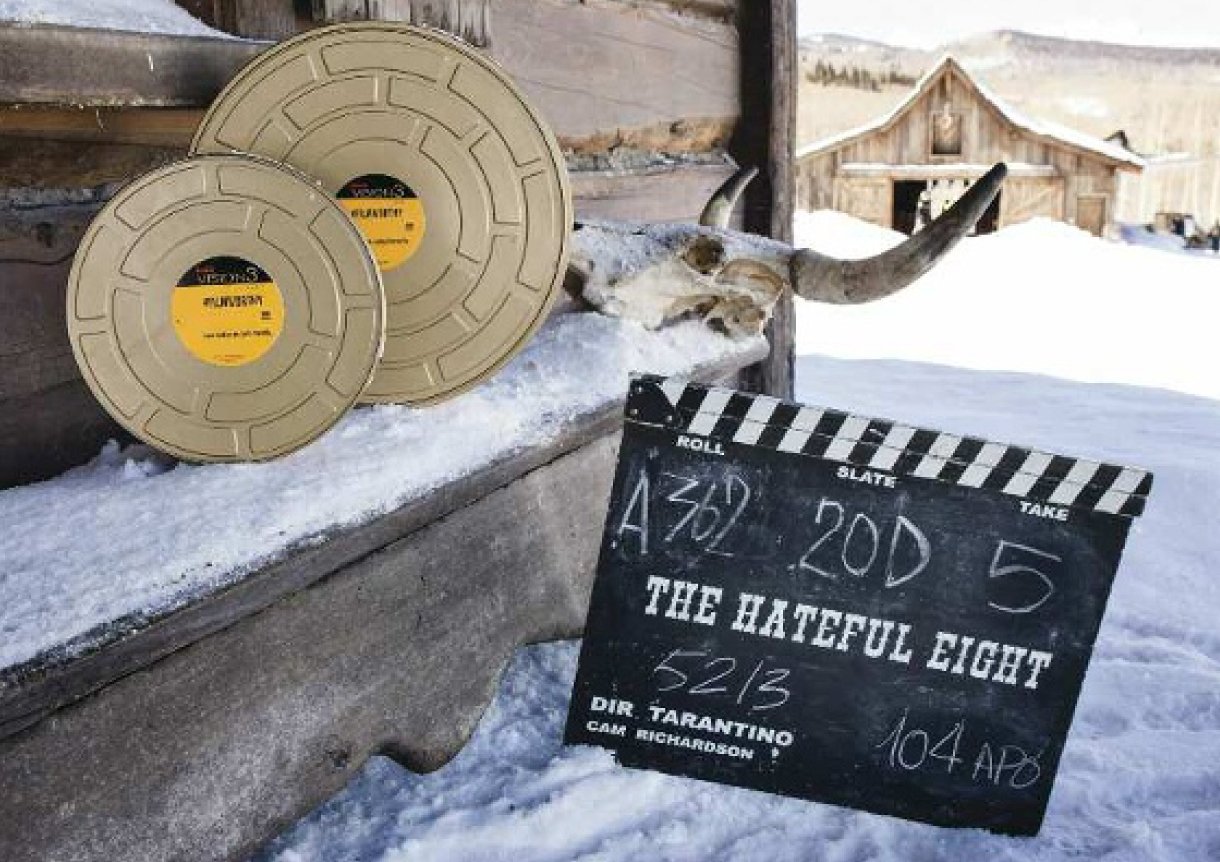

Over the course of three different test runs, Richardson and Tarantino learned not only about the lenses, but about “the durability and functionality of the camera systems and the quality of the film stock, and also the viability of the processing chain,” Tavenner notes. “Our laboratory, FotoKem, was in top form, because they have been developing and printing 70mm Imax film for years.”

The commitment to the Ultra Panavision 70 lenses, however, led to “layers of other complications,” as Sasaki puts it. Central to the equation, of course, was Panavision’s lens modification project. The endeavor involved “first getting two focal lengths to work,” Sasaki adds. “The mounts had to be modified and we had to change the spherical components to clear the camera. In an attempt to get those [initial] lenses to move, we were soaking them in chemicals.

“We were worried they would disintegrate when we took them down to their base components,” he continues, “but fortunately, back then, they made everything out of brass, aluminum and steel, so they were basically bulletproof and we got them to work mechanically. We found suitable primes, readjusted them, made new mounts, and sure enough, they actually worked.”

Through the course of the modification process, coatings, cylinders and all sorts of mechanical components were fixed, adjusted or completely replaced. A few focal lengths did have to be built from scratch with newer glass, in cases where the older glass was irreparably damaged or those focal lengths did not exist in the Ultra 70 era. But for the vast majority of the lenses, Richardson says, “the essence of the Ultras was not changed. We asked Dan to not alter the prisms because the sheer joy was that the nature of those lenses can’t be duplicated with other pieces of glass.

“I really didn’t need any diffusion with these lenses,” he adds.“There was no purpose putting anything in front of them other than NDs or 81 EFs for exterior work.”

The production carried a wide range of focal lengths, “with our widest lens being 35mm,” Tavenner states. “We did some close-ups on a 50mm that were just glorious, and some on a 200mm that were equally so. I’d say we had a good range between 40mm and 135mm, with 50mm, 75mm and 100mm serving as our workhorse focal lengths.”

As the only remaining laboratory in the world capable of processing 65mm/70mm film, FotoKem was uniquely situated to take charge of processing the production’s 65mm negative, printing 70mm film dailies, and conducting the final photochemical color-timing work.

The company used its 65mm Millennium telecine and a custom color pipeline, which incorporated their proprietary nextLab and Cineviewer systems, to provide digital dailies to editorial that emulated 70mm print film. Those digital dailies also served as a location-reference-matching tool for Richardson while he worked onstage in Los Angeles.

“In terms of shooting 65mm, we had the infrastructure,” explains Andrew Oran, vice president of operations for FotoKem’s large-format division. “For shooting 65mm on a large scale and coming up with a pipeline to emulate film [for the DCP version], we needed some refinement to make sure that it was perfect. We had worked in Ultra Panavision 70 twice before because we created new HD masters for Khartoum and It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World. So we knew the format, and we’d done 70mm prints on those titles as well. But we obviously hadn’t done an Ultra Panavision show from scratch.

“The 2.76:1 aspect ratio was not a challenge for us,” Oran continues. “With the right lens, it does it itself on the projector, and the same tools we have in digital to produce dailies that unsqueeze a ’Scope image work to unsqueeze an Ultra Panavision image.”

Kodak, meanwhile, provided reams of four different Kodak Vision3 65mm stocks: 500T 5219, 250D 5207, 200T 5213 and 50D 5203. The company made the 5219 in longer 2,000' and 1,800' rolls, as compared to the standard 1,000' rolls, so that Tarantino could film long-running dialogue scenes. That in turn necessitated Panavision’s creation of three customized 2,000' 65mm magazines. The 1,800' rolls were ultimately deemed the most efficient and were the preferred option for production. Since producing this special order, Kodak has added the longer rolls to its standard offerings.

Panavision provided special oversized matte boxes and sunshades designed to accommodate the extra-wide format. The company also collaborated with Schneider Optics to design and produce 100 Ultra Panavision projection lenses — which would ultimately be needed for the roadshow theaters across the country — in addition to a specially designed print lens for the eventual film-print master.

“None of it could have been done without these great partners,” McIntosh relates. “We were doing 70mm, but didn’t have a giant, luxurious wallet, and yet they were good about [tackling the projects] that allowed us to apply Quentin’s vision. Panavision didn’t just do rentals — they took equipment out of deep storage and brought it back to life. Quentin likes great dialogue scenes, and they are not short, so if we can print 2,000' loads, why can’t we shoot 2,000' loads? Those kinds of things were instrumental.”

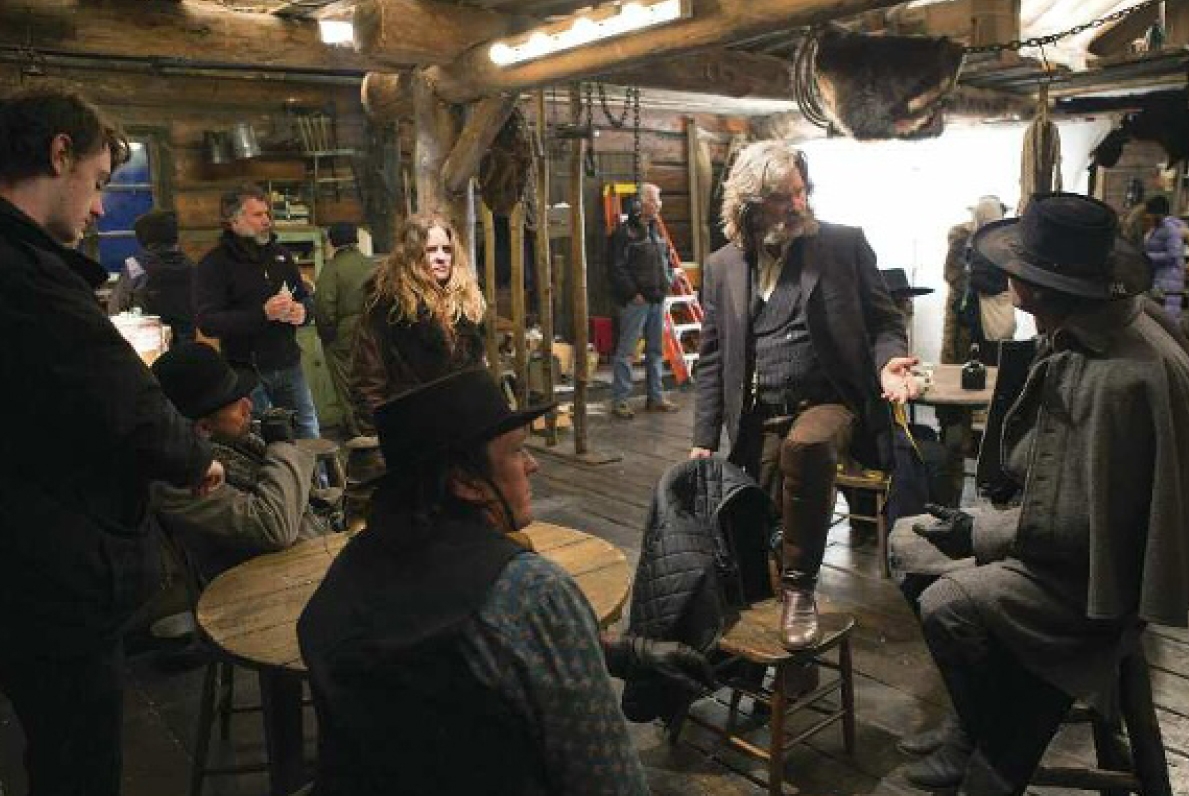

The 91-day shoot captured all exteriors at Schmid Ranch on Wilson Mesa, Colo., near Telluride. It was there that production designer Yohei Taneda and crew built Minnie’s Haberdashery cabin, a barn and an outhouse. Landscapes for horse and stagecoach sequences were shot nearby. Richardson estimates that 60 to 75 percent of the interior material was shot on location, as well.

Colorist Yvan Lucas collaborated with lab timers Dan Muscarella and Kristen Zimmerman on FotoKem’s print dailies, which were screened on location in Telluride at a small theater that was specially configured for the project, with a larger screen and 70mm film projector. When the production was in Los Angeles, dailies were screened in a retrofitted viewing area that FotoKem created for both dailies and release-print approval. FotoKem also set up a 70mm projector at Red Studios for interim viewing with the crew. Lucas also supervised the final color grade.

Tarantino says he studied It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World (shot by Ernest Laszlo, ASC) to understand how multiple lead characters could be framed on such wide lenses in the cramped quarters of an interior like the haberdashery. Both he and Richardson insist the complications were worth it.“I think this format works well in a one-room situation because you can really utilize the stage and make it a ‘thing,’ creating a complete level of intimacy,” Tarantino says. “And if you have eight or nine characters all trapped in one room, while I’m watching the people in the foreground where the scene is going on, I’m also seeing other people in the background. I’m always able to keep tabs on the characters in an almost theatrical blocking sense.”

Richardson worked exclusively with a crane and dolly, using no Steadicam or handheld techniques. Minnie’s Haberdashery was essentially divided into sections — a bar area, corner-table area, dining area, kitchen, fireplace and front room — and both camera and lighting had to travel and adapt to the different spaces while capturing all manner of action and dramatic confrontations, which were shot nearly entirely in-sequence.

“Quentin has very specific ideas about where the camera goes,” says Richardson, “and he made sure the movie was extraordinarily well-rehearsed in terms of positioning the characters inside the room. There was one moment when we had to do a little adjusting with lenses and camera to remove someone from the background so that you would not know where everyone was in the room. We altered perspective by choosing a longer lens and a slightly different angle.”

As gaffer Ian Kincaid notes when shooting with wide lenses on the tight set, “a close-up is more like a medium shot, in the sense that with the width of those lenses, you see nearly half the set — no matter where the person is within it unless they are up against a wall. That meant we had to see a lot of territory, and we, therefore, had to illuminate a lot more than we would for normal coverage. We were constantly dancing around that room, sometimes maybe three or four rounds in a day.

Richardson notes that the set also had a low ceiling, and emphasizes that “the lenses would handicap my ability to put lights where I would ordinarily want them.

“We did hard-gel the windows to try to keep them matching from shot to shot,” he adds. “That wasn’t always the easiest thing, but as the weather changed so radically with cloud cover blowing in and out, we would have [key grip] Herb Ault and his [crew] moving rapidly to put gels up in the windows as we needed them.”

Options were easier on the L.A. stage, thanks to its removable posts, beams, walls and ceiling sections. For the stage and the Colorado location, Kincaid’s team built identical overhead lighting rigs that consisted of six 6K soft boxes and strands of household bulbs stapled between the ceiling rafters and covered with bleached muslin. “Fifty 300-watt Teflon-wrapped bulbs and six of our 6K soft boxes provided a beautiful, warm and quiet glow,” Kincaid says

These rigs frequently had to come down — if they couldn’t be disguised — for low-angle shots that included the ceiling. For this reason, Kincaid explains, LEDs played a central role in maintaining the appropriate ambiance for Minnie’s Haberdashery. “We built 4-foot-long LiteGear LiteRibbon strips, [which were] about 4 inches wide, and crammed as many LEDs as we could into various small spaces — both tungsten- and daylight-balanced ones,” the gaffer says. “The haberdashery is constructed of beams, so we hid them behind upright horizontal beams, and often used them in wider shots because traditional motion-picture lights would have been [visible in the frame]. LEDs were also used in the traveling-stagecoach sequences.”

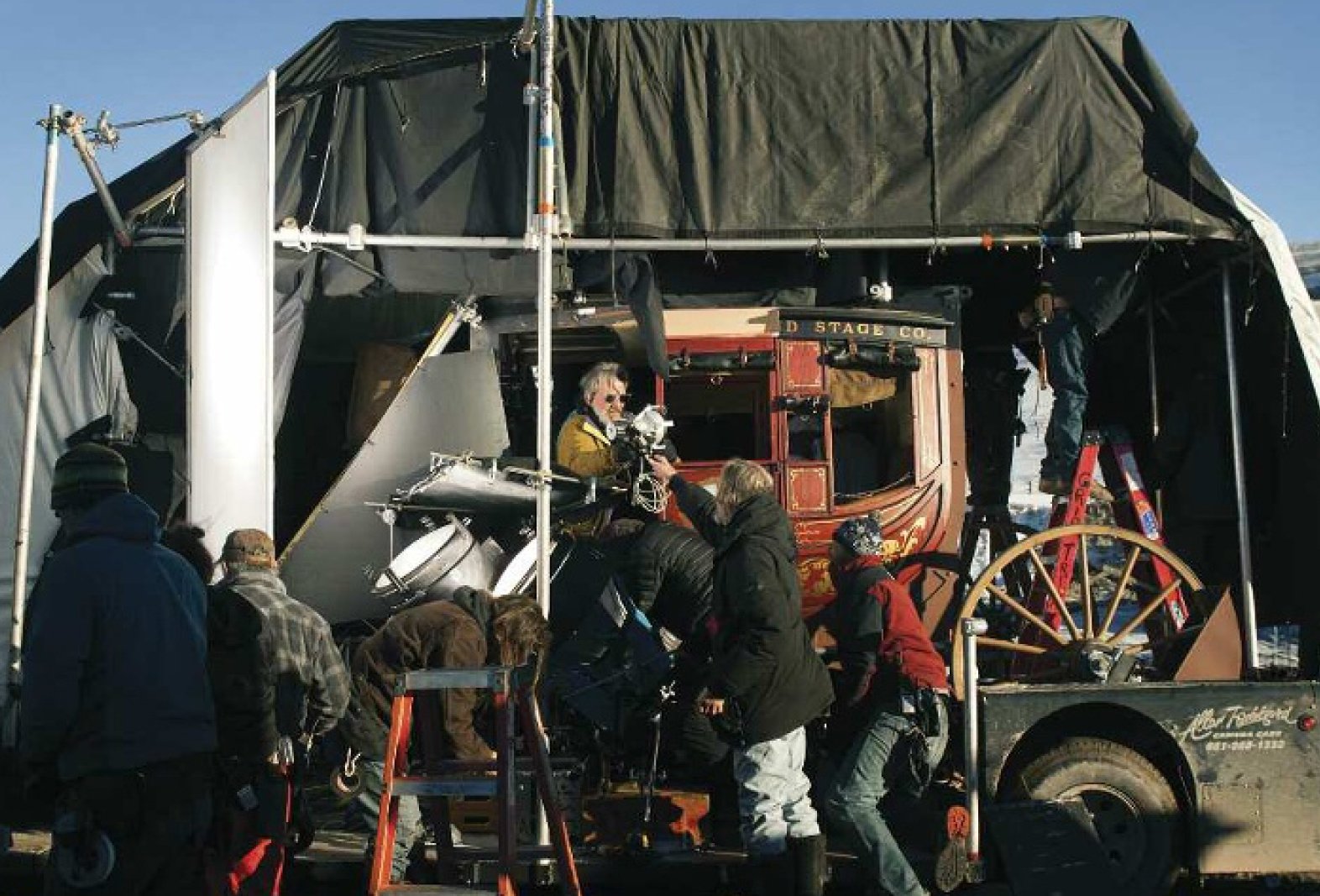

Exteriors were a constant challenge given the remote location, snow on the ground, shifting skies, and the unique format. “We couldn’t get Condors to the location with the snow so deep, so we had to use [Gradall and Pettibone telescopic construction forklifts] to lift equipment, and they were our shadow-makers [on and around the cabin],” Kincaid says. “Whenever there was sunlight hitting the windows, Herb Ault would run one of those vehicles out to put a big shadow around the cabin.”

For night exteriors, Kincaid says the production relied on two large moon boxes — each containing 16 6K space lights and filtered through a Full Blue Grid Cloth — which the filmmakers used for a gentle overhead ambiance. These units were suspended from large construction cranes around the cabin structure, as needed.

Besides Minnie’s Haberdashery, the only other significant interior was the stagecoach, where many of the characters first meet each other early in the story. The production used both a practical stagecoach as well as a stagecoach rig on a gimbal system designed by Ault and stunt driver/vehicle designer Allan Padelford. The latter set was necessary to accommodate the actors, operator, and oversized camera while maintaining the width necessary for both front and side angles.

“The [rig] had removable sides, and the camera was positioned outside the coach on its own gimbal, matching the coach’s movements,” Ault details. “This enabled us to get wide enough for the 70mm anamorphic format. Of course, this needed to be tented to control the bright sunshine. We then shot through oversized hard gels to obtain balance, while bouncing light inside the coach.”

Throughout production, Tavenner was charged with keeping the lenses safe and warm — a key responsibility, as The Hateful Eight was using the only known workable set in the entire world. Indeed, the 1st AC helped design the optics’ heated cases; he also traveled back and forth to Panavision several times to get individual focal lengths repaired or tweaked by Sasaki, on a one- to two-day turnaround when occasional problems arose.

“These lenses were a giant leap of faith,” Tavenner says. “We were taking lenses that had not been out of the warehouse in 40 years up into the mountains of Telluride at 10,000 feet in the wintertime. I had no clear idea how they would respond. We kept them within certain temperature ranges so that the expansion-contraction variables were minimized.”

The focus-pulling challenge was as complex as any Tavenner had ever dealt with.“It just came down to getting to know each lens and its physicality and mechanical adaptations,” he says, “to understand the quality of each particular lens so I could make it work during shooting. Each lens had its own individual configuration demanding certain mobility on set to achieve the same speed as modern systems. When you get to know a lens — and once you get it calibrated to where you know it is focusing where you want it to focus — then it is just a matter of keeping that system functioning that way for a 100-day show.”

In fact, everyone on the filmmaking team had to adjust their preferred ways of doing certain things in order to get maximum value out of the Ultras. Tarantino and Richardson, for example, had to revise shots due to the fact that the Panavision Ultra 70 system did not include zoom lenses. Forgoing zooms was his “biggest loss,” Tarantino says, but he feels the sacrifice was more than worth it. “I had gotten really comfortable and really facile using a zoom lens,” he says. “Then we didn’t have it. But after a while, I kind of looked at it as a good thing. Maybe I had been too facile with the zoom. Maybe I had gotten too comfortable with it. So I started looking at it as a neat thing — a fun challenge.

“We also didn’t use any Steadicam,” Tarantino continues. “But we had [already been moving away from] Steadicam before this film. For one thing, the Steadicam is too modern to use for a Western, but also, Bob has been steering me toward the use of the crane more and more. He loves the crane, and we used it a lot on Inglourious Basterds [AC Sept. ’09] and Django Unchained. But here we went even further, to the point where we basically used the crane like it was a dolly.”

Richardson adds that there are always solutions for every change in method or style. Without a zoom, he explains, “we did camera moves instead — such as crane moves. We would start at the same spot and crane to where the move was supposed to be. One of those shots is an early shot on Jesus Road — near the opening titles — where there is a statue on the road. We didn’t need a fast zoom, but something that could creep us out from a closer position, and we solved it with that move. [Tarantino] didn’t want snap zooms in this film, anyway — he didn’t want that style. But there are lots of small creeps, which we did with a dolly.

Other issues involved things like sometimes flaring the lens in an ‘overcast way, to the point where the contrast was no longer working,” Richardson adds. “When I saw that in a couple takes, I wondered if we would have to increase contrast in printing or push [the negative in processing]. I ended up pushing a fair portion of this movie by a half stop to increase the level of contrast in the lenses.”

At press time, the 70mm answer print for The Hateful Eight was being prepared at FotoKem, with Lucas working in partnership with Muscarella. “I work in the lab with the timer on the answer prints, and we take notes shot by shot about the corrections we want to make,” Lucas explains. “Then, in a few days, we see the reprint. We work roll by roll, so we watch 10 minutes at a time, instead of the traditional DI where you can make changes instantly. Here, you don’t see results until a few days later.

“But the DI [for the digital release] will also be different since it needs to match [the film print],” he continues. “I supervise the answer print for the film release first, and then I will finish the DI at my new facility [Shed in Santa Monica]. I will work with a new [FilmLight] Baselight Two [color corrector] and a Christie 4K projector projecting onto a 26-foot screen, but we have also installed a 70mm projector to screen the [film] print any time, in order to make sure the digital version retains the look and contrast of the film. This will not be a traditional DI, because we won’t be making any [power windows]. The whole idea is to stay as close to the print as we possibly can.”

With production of The Hateful Eight behind him, would Tarantino, in retrospect, have liked a crack at the Panavision Ultra 70 lenses on earlier projects like Reservoir Dogs (AC Nov. ’92) — which also featured an ensemble cast packed into a claustrophobic, single set for extended scenes? “I wouldn’t have been ready to shoot that movie with these lenses,” he says. “It was my first movie! That was challenge enough. But having said that, people did question back then why I was shooting Reservoir Dogs in ’Scope, and for almost the same reasons.”

Another Vintage Tool

Ultra Panavision 70 lenses were not the only technology literally pulled out of mothballs in order to make The Hateful Eight. To meet director Quentin Tarantino’s demand for 70mm print dailies, the production faced a dilemma regarding how to efficiently add Fostex DV40 audio-sync playback during dailies production at FotoKem. After a lengthy search, producer Shannon McIntosh located a decommissioned 70mm Officine Prevost Milano flatbed editing table that was wrapped in cellophane and stored in a warehouse of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. FotoKem technicians determined that they could, with some significant effort, modify the machine — which had been donated to the Academy by the now-defunct Boss Film Studios — to enable it to physically sync audio tracks with picture for the film dailies.

According to Vince Roth, FotoKem’s 70mm technical director, although the Prevost was intact, it needed a complete overhaul to fit the project’s needs. The work on restoring the unit was performed by Roth, projection technician Cal Orr and audio technician Brad Johnson. “It had been adapted previously to a different drive system,” Roth explains. “Initially, we thought we would have to buy a whole new controller for the synchro motor, but then our projection engineer came up with a brilliant idea to put in what is called a bridge rectifier [circuitry to convert AC to DC output] and then a big potentiometer — a voltage control system. Then we had to tear the entire thing apart and clean every single roller — everything on it — and do some rewiring for the [new voltage]. We adjusted the lamps, cleaned everything, checked the drive system, fixed a large control knob, and added an encoder for DV40 that would output time code for that sound system. But it was worth the effort, because it has excellent resolution — better than current 70mm [editing tables] I have seen — with a really nice prism block. By a miracle, we made it work.”

— Michael Goldman

Reviving Ultra Panavision 70

“Projects like The Hateful Eight are what we at Panavision relish,” says ASC associate Bob Harvey, Panavision’s executive vice president of global sales and marketing. “We listened to the filmmakers’ desires and needs and did our best to honor their vision. [Panavision’s vice president of optical engineering and lens strategy] Dan Sasaki led an entire team from technical to manufacturing to make this happen. Dan redesigned a set of 65mm anamorphic lenses to bring this format into the 21st century. When Quentin [Tarantino] and Bob [Richardson, ASC] talked about long takes, our engineers, led by John Rodriguez, rapidly designed and manufactured 2,000-foot magazines for 65mm film.”

The Hateful Eight was shot with Ultra Panavision 70 lenses on 65mm negative, and transferred to 70mm printsfor projection. (The extra 5mm print width was used in the past for soundtracks). As illustrated, Ultra Panavision optics create a mild 1.25 anamorphic squeeze of the 2.20:1 image area, which is three times the area of 35mm anamorphic. The projected image has an ultra-wide 2.76:1 aspect ratio.

As Sasaki explains, Ultra Panavision lenses were first used in 1957 with non-reflex 65mm cameras. Some of the lenses used on The Hateful Eight had to be reworked to clear the mirror shutters of the modern Panaflex System 65 Studio and High Speed (HS) Spinning Mirror Reflex cameras, which were also fitted with new motors, electronics and heaters, as well as an improved reflex viewing system.

Sasaki provided the filmmakers with 15 Ultra Panavision lenses, with eight focal lengths ranging from 35mm to 400mm. Some lenses were simply refurbished, some were recoated, and some had their spherical components swapped, while others — the 40mm, 50mm, 135mm, 180mm and 190mm — were brand-new builds.

“We kept as much of the vintage optics as we could,” says Sasaki. “The older lenses are not perfect, but they aren’t soft, either — they offer a unique quality in between. For the new builds, we would degrade the optics by changing the air gaps of the lens to induce circle aberrations, matching the visual theme of the older optics.”

Sasaki explains that circle aberrations in the Ultra lenses create “a gentle focusroll-off, a gradual blurring that tends to blend things, and enhances visual depth cues.It’s like shading the drawing of a flat circle to make it look like a sphere.” Artistically, he describes the resulting image as having a uniquely “dappled, impressionistic look.”

Producer Shannon McIntosh notes that the Weinstein Co. hired Chapin Cutler, principal and co-founder of Boston Light & Sound, to help prepare 100 movie theaters for a Hateful Eight national opening that will present the film in its native Ultra Panavision 70mm format. McIntosh states that Cutler was “brought on board before we shot one frame of film,” to allow sufficient time to source and prepare all the needed equipment.

The year-long project involved purchasing and upgrading 120 used 70mm projectors — ensuring the availability of spares. Cutler expected that about 90 percent of the theaters running the film would require a full installation that would include platters, bulbs, splicers and audio DTS playback.“The process has been mammoth. Every projector has been stripped down, put back together again, and put through tests. We replaced the bearings, gears, drive systems and motors. We retrofitted and rebuilt the lamp houses. We tried to make this ‘Murphy-proof.’”

The production commissioned Schneider Optics to design and manufacture 100 projection lenses for the short throws of multiplexes and purchased used lenses for the longer distances of older theaters. Cutler explains that they chose to use large 2K or 3K xenon bulbs “to get more light spread on the big 70mm rectangle,” adding that the roadshow lenses will be stopped down to f2.8 or f3.2 to increase the depth of focus.

— Benjamin B

TECHNICAL SPECS

2.76:1

Anamorphic 65mm

Panavision Panaflex System 65 Studio, High Speed (HS) Spinning Mirror Reflex

Ultra Panavision 70

Kodak Vision3 500T 5219, 250D 5207, 200T 5213, 50D 5203

Digital Intermediate

If you enjoy archival and retrospective articles on classic and influential films, you'll find more AC historical coverage here.

Access the every issue of AC and every story from more than the last 100 years with our Digital Edition + Archive subscription.