The Phantom of the Opera: A Silent-Era Masterpiece

Lon Chaney returns in this haunting Universal Pictures horror drama, executed with opulence and attention to detail.

When Carl Laemmle Sr., President of Universal Pictures, gave the go-ahead to begin production on The Phantom of the Opera in 1924, he firmly saw the new film as a designed sequel to the studio's runaway hit The Hunchback of Notre Dame, which had opened in September 1923 to critical acclaim and financial success. Lon Chaney's portrayal of the deformed bellringer, Quasimodo, skyrocketed him to major stardom and Universal reasoned correctly that Chaney was the key to the success of Hunchback. Within the month, story material was being sifted for a follow-up Chaney picture.

The first treatment of The Phantom of the Opera, from Gaston Leroux's 1910 novel, was submitted on October 12, 1923, by studio writers Bernard McConville and James Spearing.

Leroux's narrative was a complex mystery that melded Svengali and Beauty and the Beast. A young singer, Christine Daaé, accepts the tutelage of a mysterious, charismatic voice that issues from behind her dressing room wall. It imparts to her the measure of its art and she attains artistic heights.

She spurns her lover, Raoul de Chagny, in accordance with the selfish demands of her unseen tutor. Then the voice takes on flesh: it is the legendary Opera Ghost, a hideous living corpse that now demands her love. An Eastern police agent, the Persian, reveals that the Phantom is actually Erik, a brilliant but hideously disfigured mortal. He assists de Chagney in rescuing Christine from the Phantom's lair in the subcellars of the Opera House, where Erik dies of unrequited love for the girl.

Having purchased a mystery/horror property, Universal began to doubt those very elements. Even in the initial readers' reports planted seeds of doubt that would bear dismal fruit for the production. "The mystery angle is no asset," claimed Mel Brown, noting that few if any mystery pictures did well at the box office. "The romance needs to be emphasized," echoed Edward T. Lowe, head of the story department. His opinion meant something, as he had written the screenplay for Hunchback.

In May 1924, James Spearing reviewed the treatment of Phantom that he and McConville had prepared in the Fall. Chaney had been secured for one picture from the newly formed Metro-Goldwyn company, and now a vehicle had to be selected. Though it would be an expensive picture, Spearing felt Phantom could be magnificent and, most importantly, it offered "a perfect role for Lon Chaney." In a memo Spearing cautioned, "If we do it, for God's sake let's not botch it."

One week later, on May 17, at Universal's New York sales conference, it was announced that Chaney had been secured for an as-yet-unnamed follow-up to Hunchback, news that was jubilantly received by the attending salesmen and exchange owners. Chaney's participation in a new film automatically meant box office dollars. The choice of the proper vehicle would be critical.

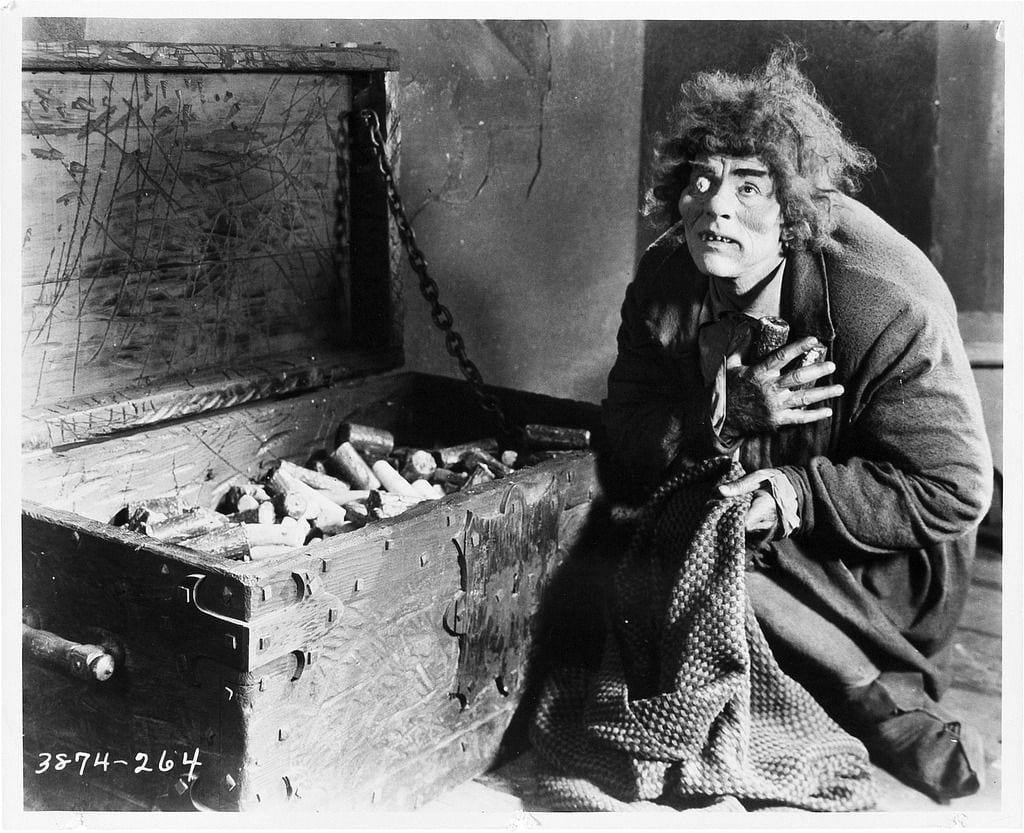

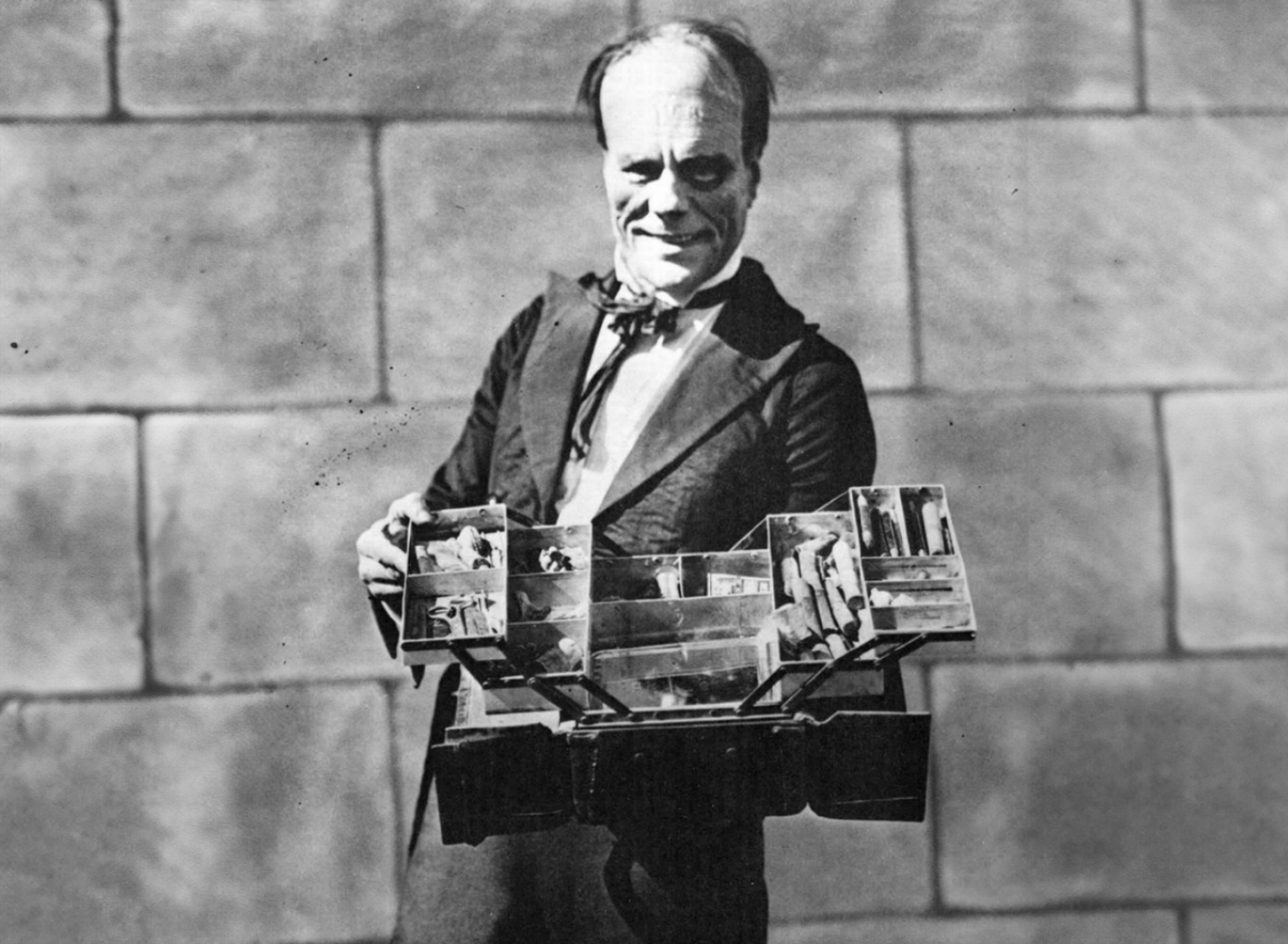

Chaney's performances were as cadenced as a dance and as communicative as classical mime. The son of deaf-mute parents, he transformed the necessary mime of his youth into exquisite pantomime in his performances. Every part of his body registered the passion of his characters. His skill with make-up and his willingness to endure torturous distortions of his own body in aid of his roles was unparalleled. If there were defined limits to his range, they had more to do with his choice of roles than his method of portraying them. Chaney had one basic portrait in him: the twisted outcast betrayed by life whose physical suffering and isolation from society force him into evil acts of violence that contradict his innate longing for love.

"I'd worked with Lon for years experimenting with one make-up after another," recalled cameraman Virgil Miller, who had photographed Chaney in several pictures prior to Phantom, and who would subsequently handle retakes on the production. "He'd say, 'Virg, make me look frightening and repulsive, but at the same time make the audience love me.' He always wanted to be loved."

If Chaney had an artistic credo, it was to convey emotion in succinct, relevant gestures and he tried to impart this belief to fellow performers. "I remember Lon telling me in the torture scene in Hunchback to not just go all out," said Patsy Ruth Miller, his co-star in that film, "because what you want to do is make the people feel what you are going through, not all of this wasted motion. Lon said, 'Never forget that acting is making the audience feel your emotion... Feeling it yourself, crying and carrying on, isn't good enough. Always remember you are acting the part and you make the audience feel it. You don't have to cry real tears,' he said, 'That's nonsense.'"

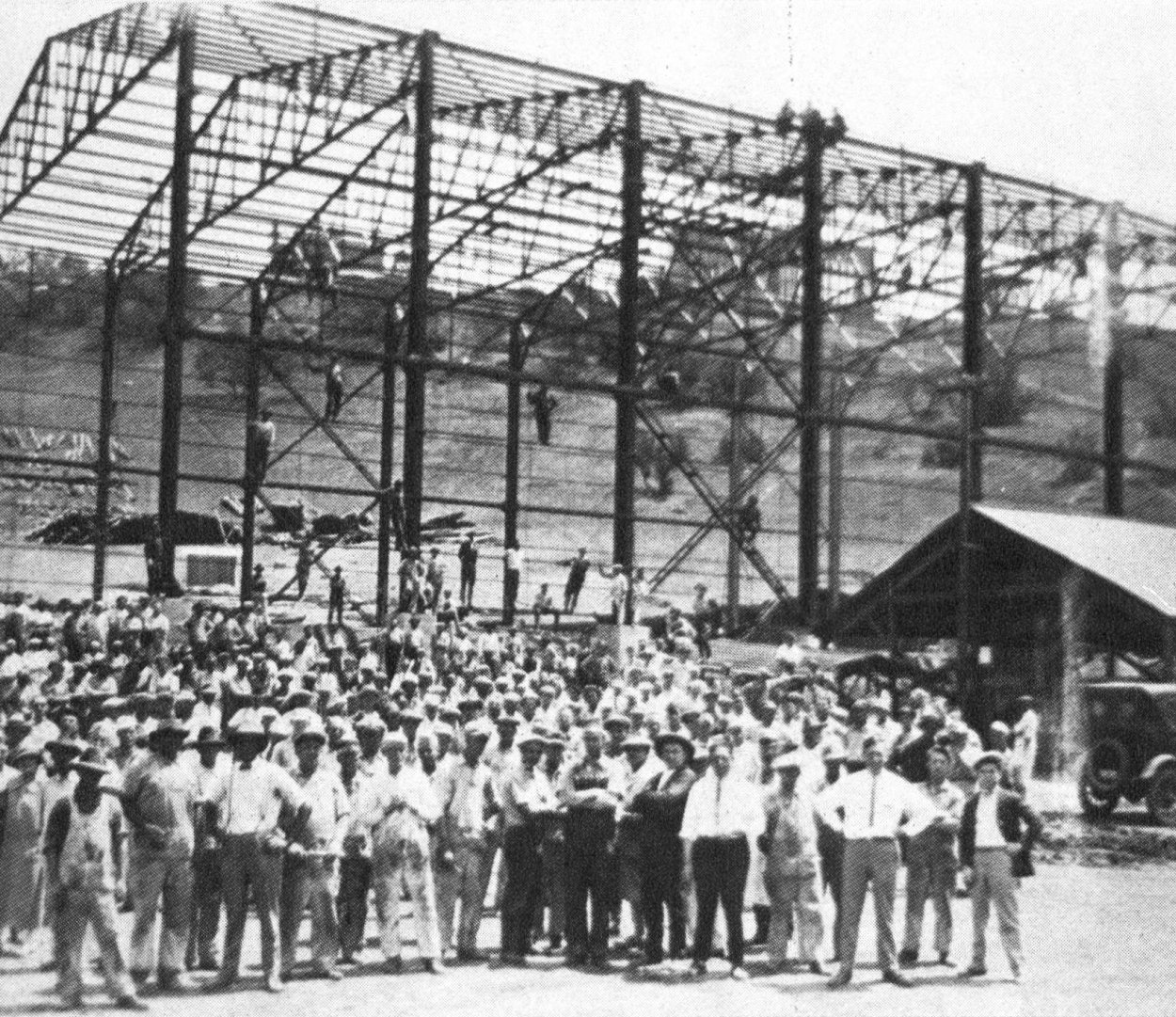

In July 1924, Universal announced that The Phantom of the Opera starring Lon Chaney would be their next super jewel, starting production on August 1. Simultaneously construction began on a full-scale replica of the Paris Opera auditorium and stage. No existing stage could house the set, so one was built. A steel frame set in a poured concrete foundation reared up on the backlot courtesy of the Llewellyn Steel Company. The Hammond Lumber Company, handling the largest order any lumberyard in Los Angeles had ever expedited, was directed to dispatch their trucks through Los Angeles en route to the Hollywood Hills; each truck, of course, was draped with a banner announcing the coming film.

Rupert Julian was chosen to direct. Born in New Zealand, his real name was Percival T. Hayes. He had been working at Universal since 1915 as an actor and director, achieving his greatest notoriety in the title role for The Kaiser, the Beast of Berlin in 1918. His career as a director had been stable and routine until 1923 when Eric von Stroheim's lavish production of Merry-Go-Round seemed headed for the same rocks that had wrecked his Foolish Wives. Stroheim had shot only 25 percent of the script and already spent $250,000. Stroheim was sent packing and, overnight, Rupert Julian was brought in to mop up.

Julian completed Merry-Go-Round in an efficient manner and close to budget. It made money and appeared on many "Ten Best Pictures" lists of 1923. Julian's reward was to be elevated as Universal's prestige director and with The Phantom of the Opera, he was assigned to the most ambitious production the studio had ever undertaken.

In some ways, Julian bore a superficial resemblance to Von Stroheim, dressing impeccably and conducting himself like a martinet. "He looked very severe," recalled actress Ruth Clifford. "He was extremely dignified, and that little waxed mustache — it wasn't caricature, it was really a stunning mustache. He was always beautifully groomed, a little flower in his buttonhole, and he was very, very strict."

Elliott J. Clawson, Julian's scenario writer since 1916, began the screenplay by discarding the rubbish that had crept into the Spearing-McConville treatment. They had chosen to make the story revolve around a flirtatious Christine, fickle and vain, with the Phantom seemingly just another troublesome suitor. Clawson stuck to Leroux, but was hampered by his ignorance of the specific geography of the labyrinthine Paris Opera House. C. Richard Wallace, assigned to the picture to develop incidental comedy, remembered an acquaintance who had worked at the Opera, a Frenchman named Ben Carré who was now an art director in Hollywood.

Carré knew Leroux's book well and had been trying to interest director Marshall Neilan in filming it. Carre answered Wallace's summons for help and discovered Julian and his writers at loggerheads in a story conference. In his unpublished memoirs Carre writes, "after a long talk my descriptions did not advance them any more than the suggestions in the book." This may have been due to the fact that Carre never mastered English, and his brazen Franglais was frequently unintelligible.

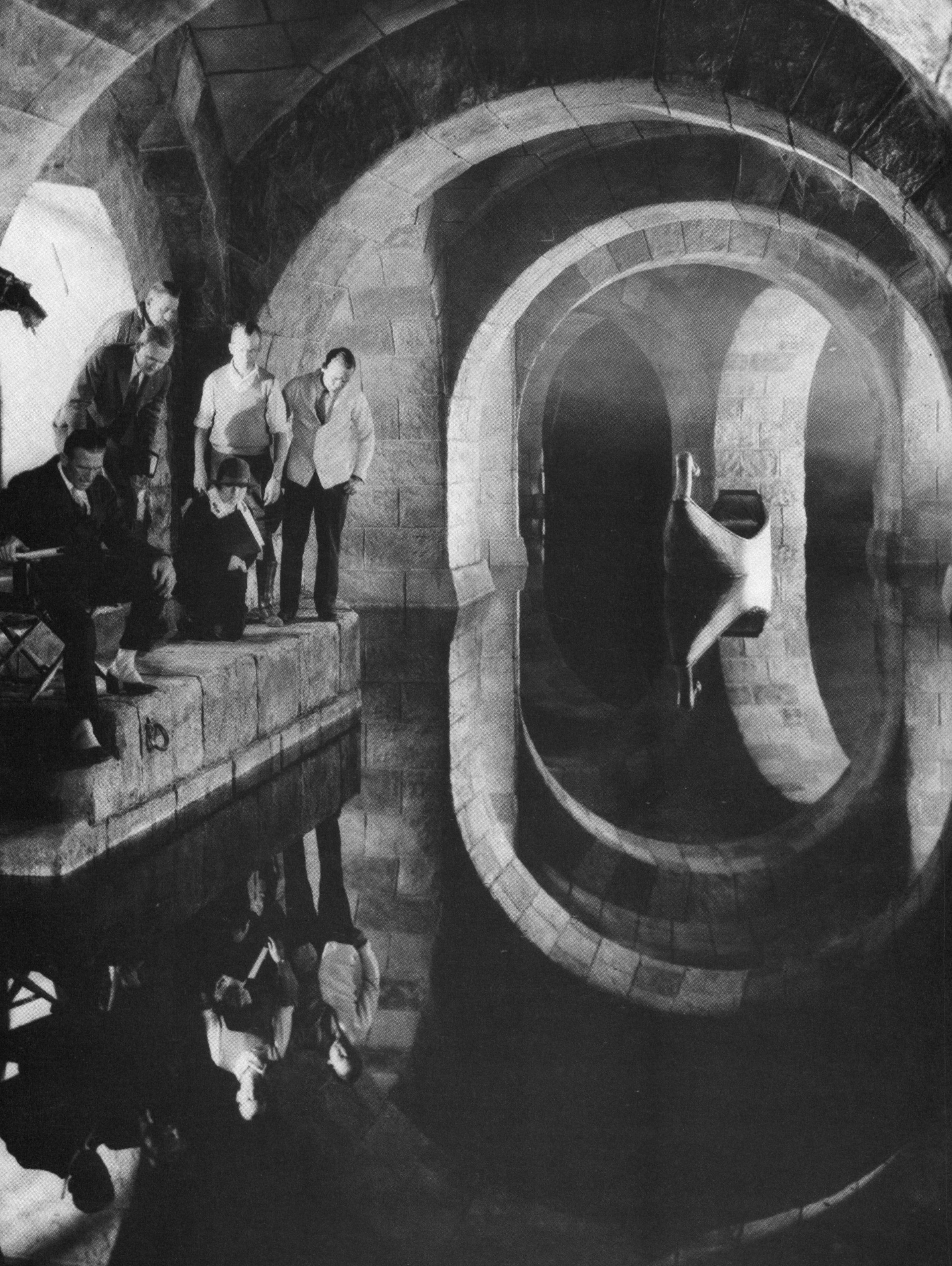

Aware that Leroux had created his descriptions of the Opera cellars from whole cloth, Carré did likewise, assuring Julian that not one in a million had ever seen beneath the stage. Carré furnished 24 finely detailed charcoal sketches highlighted with white chalk, illustrating specific locales from the novel. The writers now had a guidebook to the Phantom's underworld. The movie also had, unofficially, a production designer.

Carré departed, expecting to be recalled later to supervise construction of the sets. When the film went into production he was in Europe, and it was not until he was shown a print in the 1970s that Carré was aware that his designs had been incorporated into the film. Clawson's debt to Carré is evident in the script. Time and again he notes "This is a Ben Carré set," or, "Carré is working out the details."

The practical design of the Opera House and all other sets in the "real" world were handled by Elmer E. Sheeley and his assistant, Sidney Ullman. There is no basis for the endlessly repeated myth that Charles "Danny" Hall was the art director on Phantom. In fact, Hall was off with Chaplin on The Gold Rush the entire time Phantom was in production.

There was a Hall in the Phantom art department. Danny's brother, Archie, was responsible for overseeing the physical construction of the sets, a function he had also performed on Hunchback.

The Opera House was the "money set" and the big marketing gimmick that Laemmle was counting on to put over the advertising. Clawson was aware of this and submitted page upon page of reverential data noting every aspect of the building's history. Studio researcher Meta Claire Stern had uncovered the esoterica in an 1879 issue of Scribner's magazine, and the incorporation of this research in the scenario was a signal to the front office that the huge investment in the sets was understood. Until Ben Carré came to their aid, it also obscured the fact that the writers didn't have a clue to the building's layout.

The reconstruction of the auditorium (the stage that houses it is 360 feet long by 145 feet wide and still stands today at Universal City [rather it did, until 2014]) proved impossible to photograph. "When they built it, the damn thing wasn't large enough," recalled Phantom director of photography, Charles Van Enger, ASC. "For the long shots, we had to take the camera out of the stage and halfway up the hill."

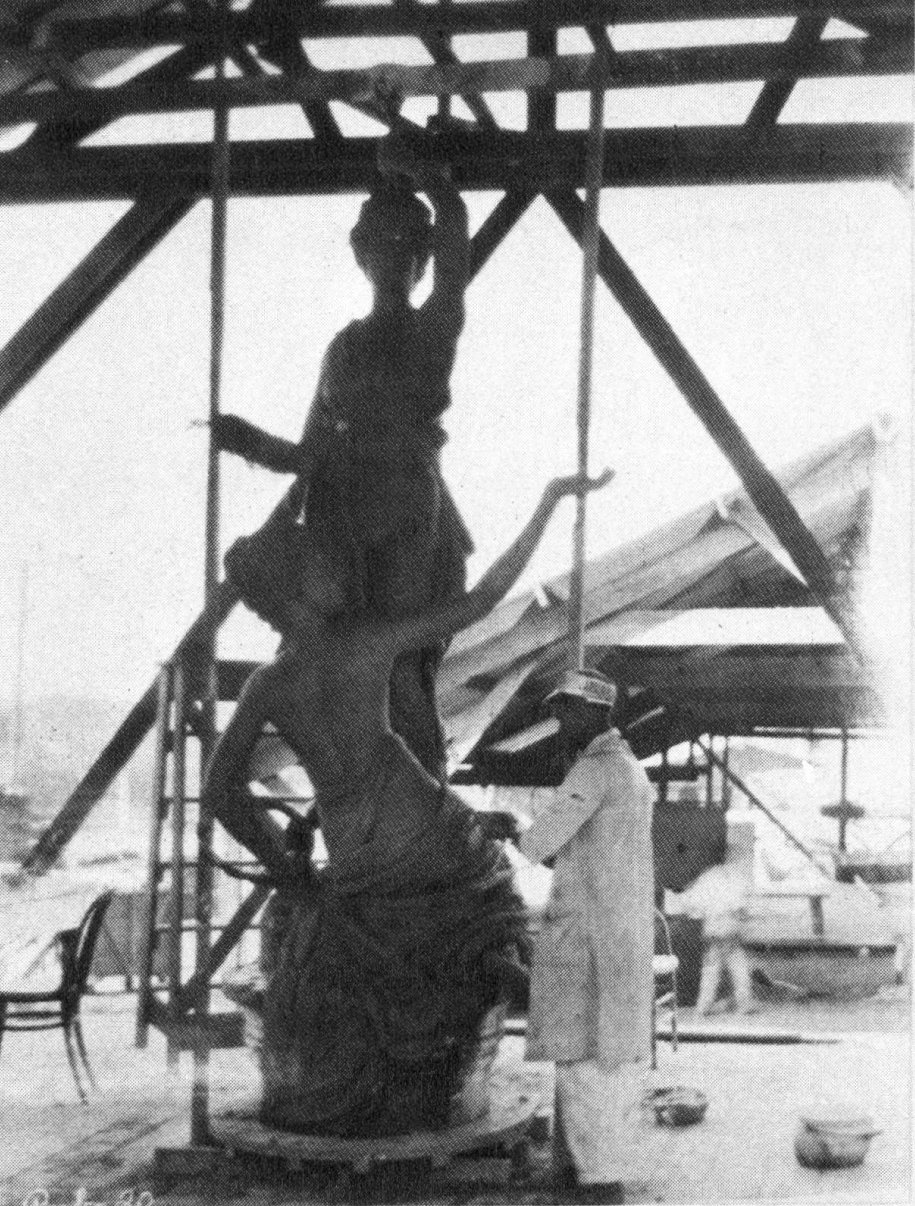

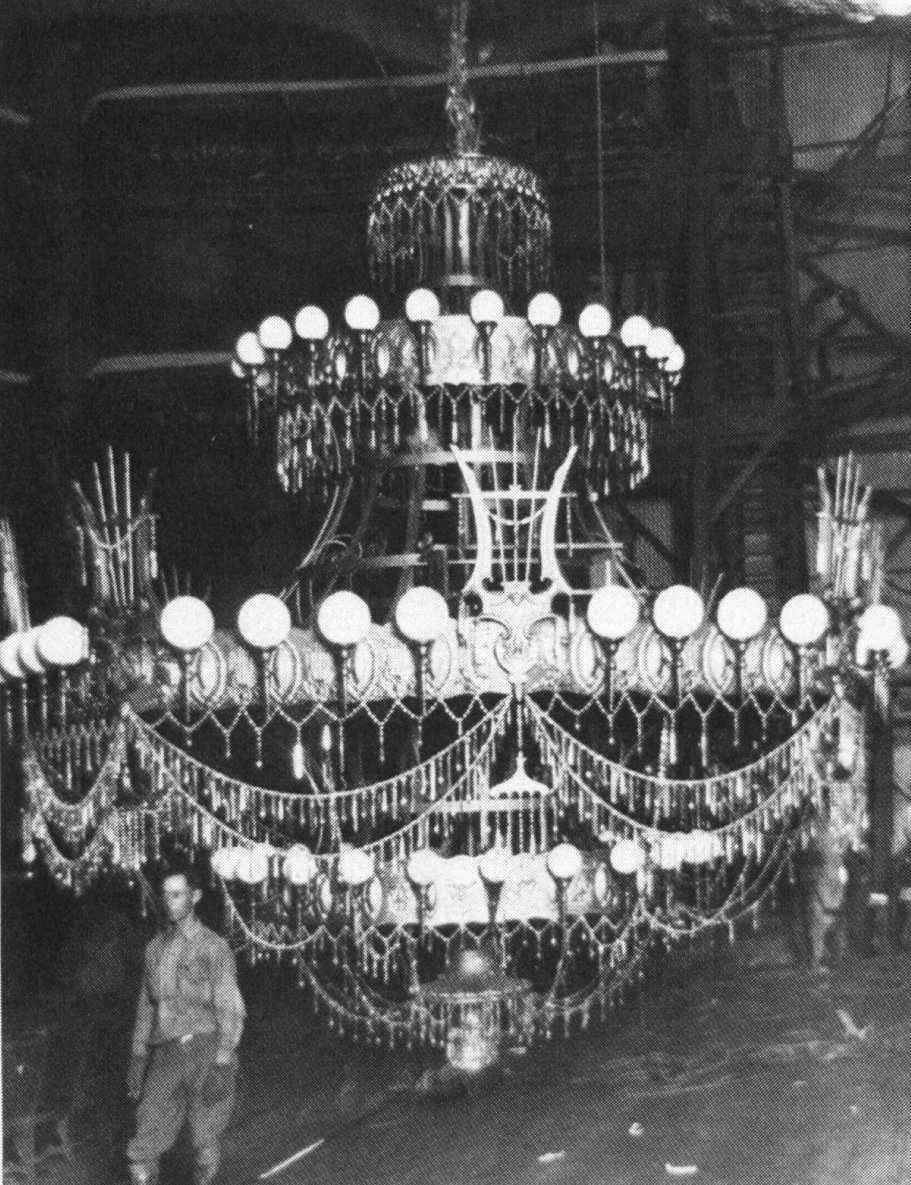

Laemmle was going to play his investment in these grand sets for all it was worth. Sequences in the auditorium and on the Grand Staircase were all noted in the scenario as "Prizma," a natural color process developed by William Van Doren Kelly, which was enjoying a brief commercial life. Production supervisor Benny Zeidman authorized the hiring of eleven sculptors and scenic artists who labored six weeks creating sculptures and interior decorations, including a full-scale copy of the statue of Apollo that adorns the roof of the Opera, and the central chandelier which, in Leroux's story, is cut loose by the Phantom during a performance. Studio manager Julius Bernheim sent scouting parties to Europe to procure Fin de siècle furnishings and operatic props.

One prop returned from this scavenger hunt solved a sticky moment in the script. In describing the decor of the apartment the Phantom prepares underground for Christine, Clawson had effused over a bed: “This is an extraordinary bed, a dramatized bed, something which does not exist." Actually, it did. A fanciful and wholly surreal bed, like a gilded gondola or slipper, was purchased at an auction of the effects of the notorious European entertainer Gaby Deslys. Its fanciful appearance was made to order, and its contrariness obviated Clawson's nervous suggestion in later drafts to make it more of a couch to placate carnally-minded censors. Twenty-five years later it saw service again in Norma Desmond's bedroom in Sunset Boulevard.

The initial scenario was a faithful transcription of the novel that retained the personal histories that allowed the Phantom and Christine to be drawn together. Their imperatives lie in their pasts. For Christine, it is the memory of a loving father. For the Opera Ghost, it is the mother, repulsed by his deformity, who withheld her love. Human links to their respective pasts appear. Christine's aged aunt, Mama Valerius, rekindles Christine's childhood, while the Phantom is pursued by the Persian, a former associate with a score to settle.

Clawson pared Mama Valerius down to a few brief scenes that constituted mere chaperonage and illustrated her bourgeois home life; without these scenes, Christine has no life beyond the Opera. Through Mama Valerius, we also learn the reason for Christine's faith in her unseen master. Her father, an itinerant musician, had spoken to his child of the Angel of Music. Christine believes that her dead father in heaven has interceded and sent the Angel, the voice in her dressing room. Knowing this, the Phantom strengthens his hold on her imagination by instructing the girl to be at the lonely graveyard in Brittany at midnight where he plays "The Resurrection of Lazarus" upon a violin at her father's grave.

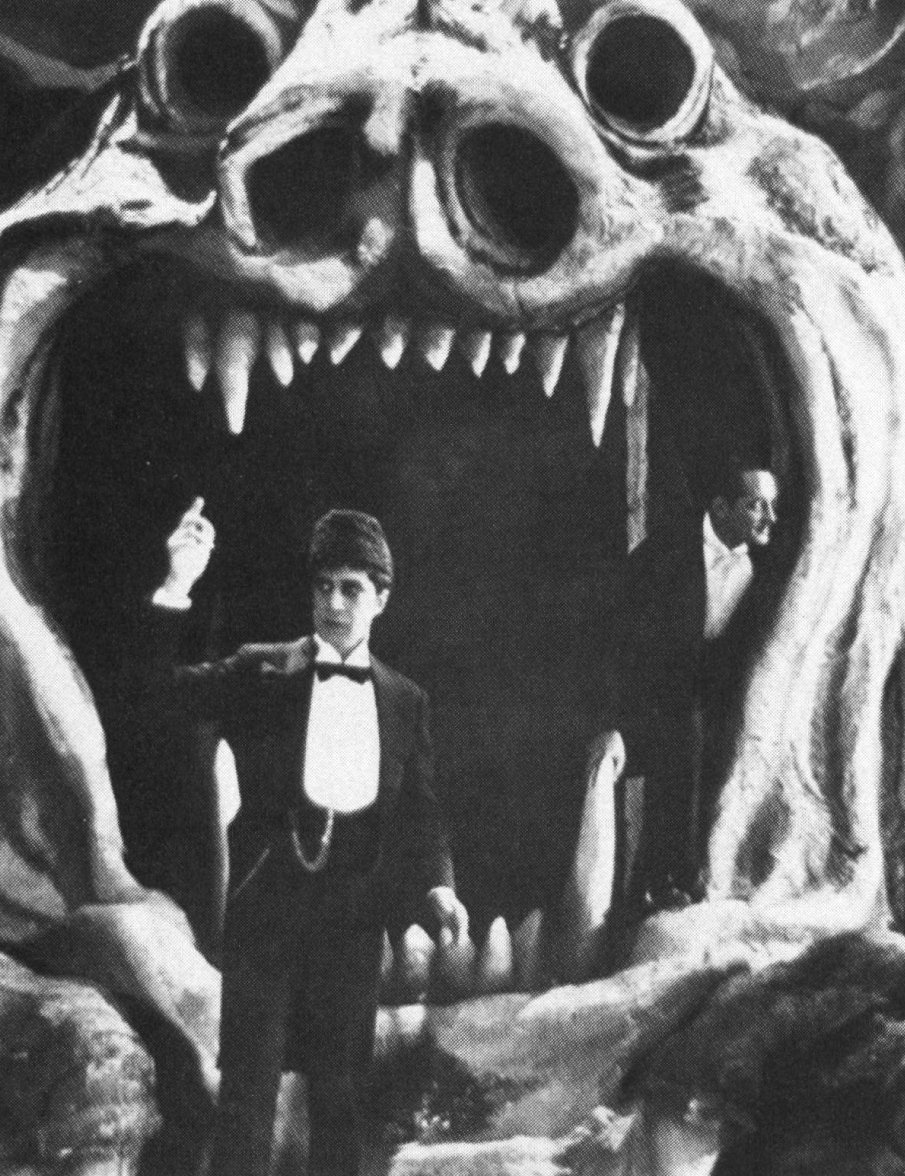

The character of the Persian wanders about the edges of Leroux's narrative until the mid-point where he explains himself and the Phantom. "I first knew Erik in Mazanderan," he explains, and Clawson seized the opportunity for a lengthy flashback in which the Persian is seen as the "daroga," or chief of police. Erik — the Phantom — is depicted as a conjurer and executioner in the Sultan's court where his skill with the strangler's lasso is useful in throttling condemned prisoners for the amusement of the Sultan's wicked daughter. His artful manner with the rope verges on the fantastic, and Clawson suggested trick work or cartooning to display the effortless grace with which Erik pulls down his victims.

Erik falls from favor with the Sultan and is sentenced to be eaten alive by ants. Under cover of night, the daroga steals out to his friend and discovers Erik, still alive, manacled face down on the anthill. Freeing him, the daroga is seized with horror as he turns Erik over revealing the unhappy results of the insects' work. "Later," concludes the Persian, "he took refuge in the Opera to be near the music he loved, to hide his ugliness, to carry on his worthless life."

Gaston Leroux had placed Erik in Persia at the Sultan's court, but had him born a misshapen genius whose tragedy was the entrapment of his inner gifts within a hideous body, as in the Beauty and the Beast fairy tale. The anthill was Clawson's own contrivance.

By rationalizing the disfigurement, Clawson was attempting to bring day-to-day logic to a fairy tale. Its gruesomeness actually was in keeping with the thread of grim details he had retained from the novel: the manifestation of Erik's fiery eyes in de Chagney's bedroom; the illusions of Erik's torture chamber that confront the heroes with wild animals and walls of fire; and the pivotal Perros graveyard scene where de Chagney follows Christine to the graveyard and confronts the Phantom in the moonlight as Erik pitches skulls from a disinterred bone heap at Raoul's feet.

But the studio had always desired to reduce the macabre quality of the narrative and increase its romantic values. In 1924, there was no tradition of horror films to build on, and Chaney's grotesque character in Hunchback was just one of three key ingredients, the others being spectacular settings and a strong love story. Clawson's script was mauled in subsequent story conferences. The torture chamber was retained but the scene in de Chagney's bedroom was manually slashed from the next draft, along with the graveyard scene. A handwritten note from Clawson, amended to the revised script page, laments, “Sequence in the graveyard at Perros is eliminated as a result of the decision at the story conference. It seems unfortunate that the pictorial value of the graveyard should be lost."

Clawson must have fought mightily for the scene. A drastically revised version of it was reinstated in the third revised script. The Phantom's shadow was to be seen on the wall playing the violin while Raoul looked on, baffled. This was still too grim, and the scene was changed to Raoul, concealed, watching solemnly as Christine sobbed at her father's grave in the moonlight.

At this time the entire Persian flashback was also jettisoned. Budget may have been a consideration as deleting it removed several sets, actors, process shots and numerous shooting days. Dramatically it was a wise decision as the story already had one lengthy flashback, Christine's recitation of her experience in the Phantom's lair. The Persian was given an unwieldy chunk of intertitled dialogue to explain the days in Mazandaran, and Minnie, a five-ton circus elephant and former mascot of the Kansas City Shriners, never got to don her gold and velvet howdah for her proposed screen debut in the Persian sequence. (Minnie had been purchased specifically for the picture — ah, cruel fate!)

Universal was probably delighted to be rid of Clawson's anthill episode and returned to Leroux's premise of biological deformity. As an afterthought, a stray line of dialogue placed Erik as chief inquisitor in charge of torture during the revolutionary period of the Second Commune when the Opera was used as a prison. This detail was drawn from Leroux and explained Erik's presence in and remarkable knowledge of the Opera House.

The ending was a problem. Leroux had written a protracted diminuendo of anguish and pain. As the Phantom forces Christine to become his bride in exchange for sparing Raoul's life, she bestows a compassionate kiss on his hideous face that shakes Erik to his soul. He weeps that he has never known a woman's kiss, that his own mother would shrink from him in horror and toss him his mask. Her kiss, born of pity for his suffering, destroys the Phantom. He sends the lovers away and dies quietly, alone, in the bowels of the Opera.

Such an ending, no matter how properly motivated dramatically, would not send Universal's patrons home happy. The studio already had the sour experience of a morbid ending with the expensive failure of Foolish Wives, and McConville and Spearing had at the very first changed the ending to a traditional rescue with the Phantom shot dead by the Persian. Commercial tastes demanded a dynamic finish and Clawson now obliged, at the same time trying to salvage fragments of the sad majesty of Leroux's ending.

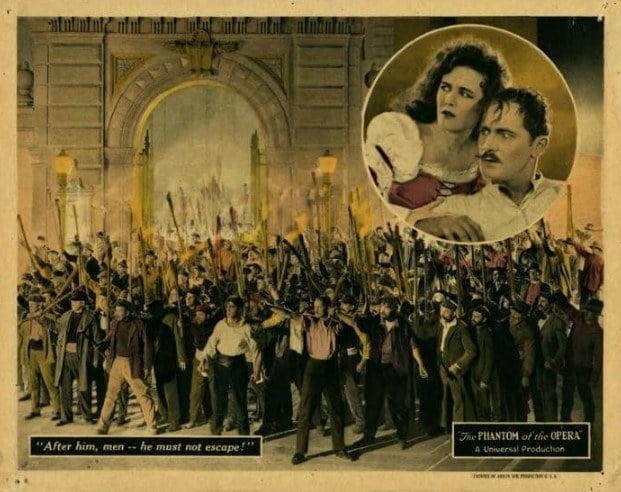

An early incident in the novel has a stagehand murdered by the Opera Ghost. Clawson or Wallace seized on this and created the character of his brother, Simon, also a stagehand and bent on avenging the death. Simon was woven through the narrative demanding satisfaction, to be brought forward at the climax as the leader of an avenging mob. Paired with another new character, mincing propman Florine Papillion, Simon also became a comic straight man, scattered throughout the story with his partner to provide comic relief.

Clawson's very first ending had Christine sit passively as Erik planted a kiss on her forehead. By the third revised script, she took the initiative, with the Phantom reacting to her selfless gesture like a wounded animal. "Even my own mother would never kiss me," he moans. With this glancing salute to Leroux's pathos, the mob approaches. Erik scoops up the girl and flees through the Opera House to the street, allowing free production value from the standing sets for Hunchback ("It is understood," notes the screenplay, "that all Notre Dame sets will be so modernized as to conform to the period of 1890.").

The Phantom commandeers a barouche and drives recklessly through the street. The carriage overturns and Erik springs to the nearest building and crawls upward like a bat. As he is trapped between two factions of the mob, he produces a black satchel and withdraws his strangler's lasso. He twirls the rope and it catches on a bridge ornament. Erik swings diagonally over the street to another building where he laughs down in triumph at his pursuers.

Simon appears in a window behind him, forcing the Phantom to swing out into the street. With the mob waiting on the other building, Erik begins to climb up to the bridge, hand over hand. Simon gains the bridge and waits for Erik's ascent, cutting the rope with a clasp knife. The Phantom plummets to the street below. As Raoul and Christine embrace, the Persian pushes through the crowd to where Erik lies mortally wounded.

"All I wanted was to have a wife like anybody else," whispers the dying Phantom, "...and to take her out on Sundays." Florine Papillion appears, carrying one of Christine's lost shoes to add a comic touch for the fadeout.

This seemed to provide the popular appeal the studio wanted, but it wasn't left at that. Another ending was ordered. This time, as Erik and Christine flee the mob, they pass by her home. She indicates they should take refuge there. Erik cringes on the threshold "as Satan before the cross." As he enters her rooms, he is overcome by the sense of her life that the rooms impart. He tells her he is dying, asks if she will kiss him, and presents her with a wedding ring. "It will be my gift to the little chap you love."

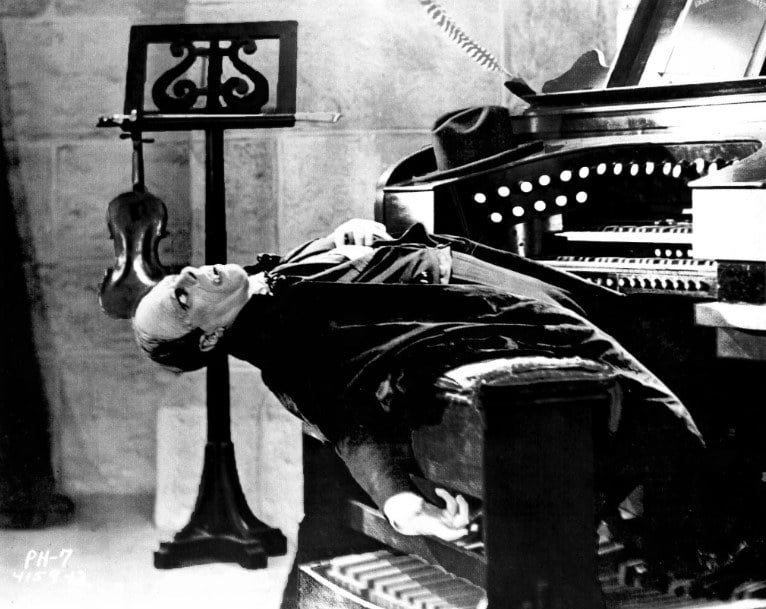

Simon, Raoul and the Persian break in. Christine pleads protectively that Erik is ill, but the wedding ring rolls across the carpet as the Phantom slumps to the floor, dead. Sobbing, Christine flees to her garden where Raoul consoles her. The problem of the ending did not go away. Whether of his own determination or with front office approval, Julian ultimately filmed yet another, unscripted ending where the Phantom died at his organ, just as he filmed the Perros graveyard scene as initially written. Neither sequence survived into the general release print.

The Phantom of the Opera — Part II

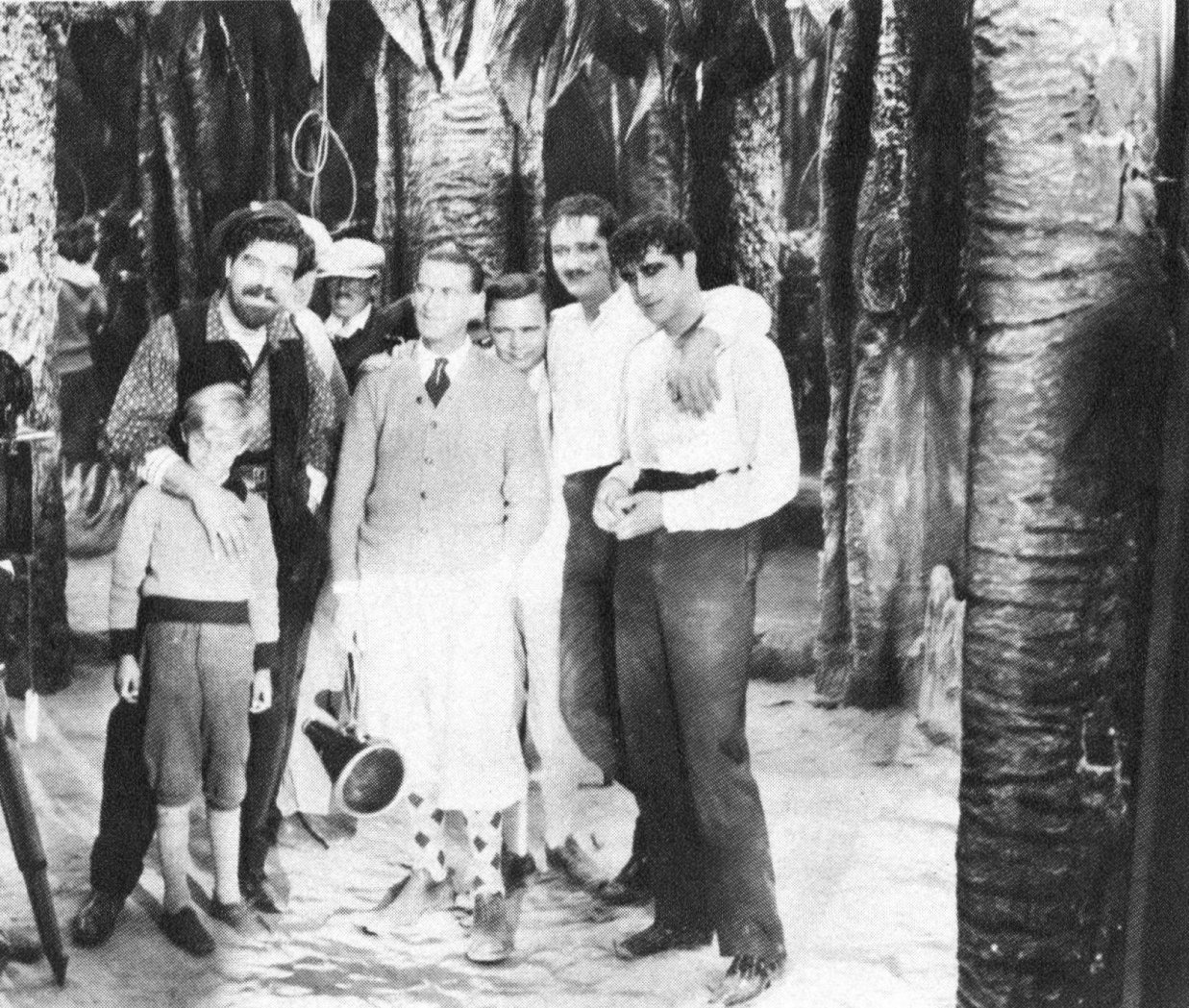

The Phantom's planned August 1 start date came and went as construction of the sets lagged behind. After a September publicity stunt fingering every top female star as a candidate for Christine, the studio finally announced in October that Mary Philbin, a 19-year-old ingenue being groomed for stardom, would co-star with Norman Kerry. They had already teamed with Julian for Merry-Go-Round (Kerry, too, had been the romantic lead in Hunchback).

The Phantom of the Opera would be Universal's prestige release of 1925, and the public would be kept aware of it for nearly a year before its opening as a high-priced roadshow attraction.

In line with the desire to recapitulate Hunchback's success, the setting would be historical Paris with the action centered around a slavishly duplicated copy of a famous landmark. Chaney would be recast as a hideous but pathetic outsider whose actions interfere with the love affair between Philbin and Kerry, and he would unveil yet another remarkable make-up.

Chaney's make-up was as carefully measured as his performances. He had a thorough understanding of make-up as it related to cinematography and he experimented aggressively with cameraman friends like Virgil Miller to master his understanding of lenses, viewing distance and color sensitivity. He was keenly aware that his make-up had to be a flexible extension of his own face that gave him full range of expression. That he achieved such conviction with the humble materials of the time only increases respect for his craft.

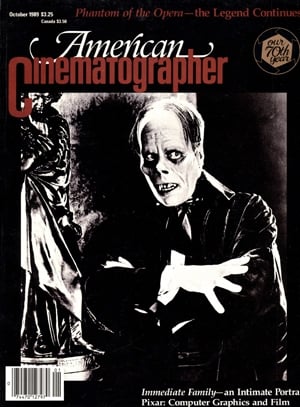

“I'm supposed to have evolved some magic process of malforming my features and limbs," Chaney observed in a rare testament of his craft. “It's an art, not magic. In The Phantom of the Opera, people exclaimed at my weird make-up. I achieved the Death's head of that role without wearing a mask. It was the use of paints in the right shades and the right places — not the obvious parts of the face — which gave the complete illusion of horror. My experiments as a stage manager, which were wide and varied before I jumped into films, taught me much about lighting effects on the actor’s face and the minor tricks of deception. It's all a matter of combining paints and lights to form the right illusion.”

To create the Opera Ghost, Chaney had to transform his features into those of a living skull, using a color plate by Andre Castaigne from the book as a model. The contours of his cheekbones were raised from within by stuffing wadding inside his cheeks and an exaggerated skullcap raised the height of his forehead several inches to enhance the dome of the skull, its bald crown encircled with limp wisps of hair pressed flat. Carefully drawn pencil lines embellished the furrows of his brow and masked where the skullcap met his own forehead. His ears were glued flat to his head.

The sockets of his eyes were painted black with white highlights under the eye to suggest the turning of the bone into the socket. Small prongs attached to a set of decaying teeth created the perpetual grin of a skull and held the mouth open. The grin was enhanced with greasepaint which altered the contours of Chaney's own lips. Putty sharpened the angle of the nose with the nostrils painted black to resemble the nose holes of a skull. Two loops of wire were finally inserted in the nostrils and guide wires hidden under the putty actually pulled his nostrils painfully upward, flaring and upturning Chaney's own broad nose.

“He suffered, you know," recalled Charles Van Enger, the principal cinematographer on The Phantom of the Opera. “He had two wires on his nose that pulled it up and sometimes it would bleed like hell. We never stopped shooting. He would suffer with it."

But the Death's head needed a corollary: the mask it hides behind. Leroux was of no help here. Chaney's original design was ingenious: a half-mask with sad painted eyes like a porcelain doll, a tentative wisp of linen trailing down to conceal the mouth.

Chaney's value to the film gave him almost limitless power, and with directors like Tod Browning and Wally Worsley, Chaney had little trouble imposing his will. Unfortunately, his director for The Phantom was not a crony who could be told what to do, but the difficult Rupert Julian, who was not about to defer to anyone, even his star.

Apart from his assistant, Robert Ross, Julian's entourage invariably included his highly vocal Australian wife, Elsie Jane Wilson, herself a former actress and director. She had definite ideas about what was transpiring before the cameras and had no qualms about voicing her opinion. Chaney was already disagreeing with Julian about how Erik should be portrayed. Now, it seemed he had two directors.

There was also Julian's dog to contend with, padding about the stage after its master. Julian even engineered a cameo appearance for the big mongrel, extant in some prints today, where it lopes into frame to bury a bone "in a garden near the Opera House!"

The schedule was laid out to accomplish Chaney's work at the outset as he had other commitments pending. His first MGM film, He Who Gets Slapped, would be released in November, and Roland West had already signed Chaney for The Monster, slated to film as soon as Phantom wrapped.

Production hadn't proceeded far beyond its mid-October start when the inevitable clash of two intractable egos occurred.

"It was a terrific strain," said Charles Van Enger, "because Chaney and Julian wouldn't talk to each other. I had to be the messenger boy. Rupert would say, 'Tell Lon to do this,' and I'd go over and tell Lon, 'He wants you to do this,' and Lon would say, 'Tell him to go to hell.' I'd go back and I'd say, 'He says to go to hell.' So Lon did whatever he wanted.

"Can you imagine Julian telling Lon Chaney how to act?"

Elsie Jane stepped into the fray and tried to lighten the tension of the set with jokes, many of them at Julian's expense. She would refer to him in front of the crew (who, by now, had turned against him) as "the Australian barber." The absurdity gave cheer and comfort to the harried technicians. "Shave-or-haircut?" they mercilessly called him. At the end of one particularly difficult scene, someone shouted out, "Next!" — throwing the entire company into a state of suppressed hysteria.

There was no love lost among the supporting cast, either. Norman Kerry was on horseback for a set-up when he lost patience with Julian's pomposity. As Van Enger remembered it, Kerry abruptly turned his horse and charged straight at the director's platform, riding down the cameras in the process.

"I told Rupert," said Van Enger, "that if he wasn't careful, someone was going to drop a lamp on him. Well, it's lunchtime. We walk on the stage and there's not a soul about. And as he walked in, it was just like fate: a piece of board fell down from one of the sets, hit him on the head and scratched his face."

Julian's handling of the sequence in which the Phantom causes the great chandelier to fall during a performance confirmed to Van Enger the director's deficiencies. Rigged to a rope and pulley system, the full-size chandelier would be lowered slowly into the auditorium while the cameramen undercranked their cameras. Projected at normal speed the chandelier would appear to plummet into the orchestra loge.

"I had the whole top of the stage covered with Cooper-Hewitts [mercury-vapor lights]. Then I lit the set," recalled Van Enger. "When the chandelier fell, all the lights would go out except the Cooper-Hewitts, which would supply a soft glow. Julian said he wanted everything to go black when the chandelier fell. Well, you know what would happen if you dropped the chandelier on all those people and you don't see it!"

"We used to have a blue glass we looked through to judge contrast. And somewhere I had found a blue poker chip, and I was playing with it like you'd play with a bunch of keys. Julian is saying, 'You've got too much light on this — it's supposed to go black! Let me see your blue glass!' I handed him this poker chip, and he put it to his eye and said, 'Just what I wanted!'

"He couldn't see a goddam thing."

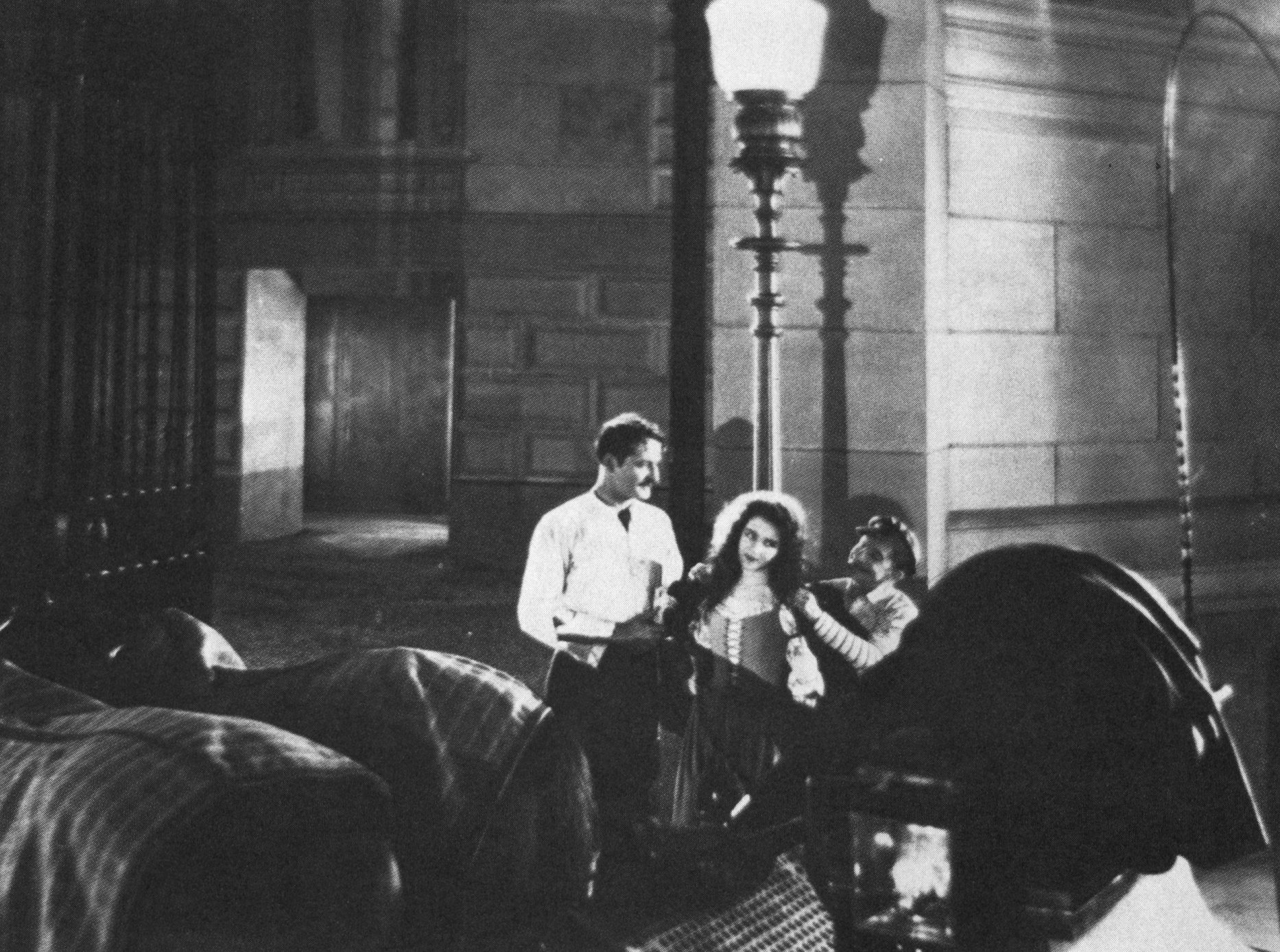

Van Enger's patience wore thin when he saw a pattern developing that was putting them behind schedule. Julian was endlessly taking and retaking Mary Philbin's scenes and the front office was blaming Van Enger for the delays.

"He'd fix her dress and we'd take it again, and he'd fix her leg and take it again — and we did this about 30 times." Convinced that Julian was acting out of an attraction to the girl, Van Enger confronted him. “Finally, I said, 'Rupert, what the hell are you doing? One take's exactly like the other, and if the scene is three feet long on the screen, that's a lot.'

"'Well,' he said, 'I don't like the lighting.'

"I said, 'You've liked the lighting the last 30 times, and that's the way it's going to be. I'm not going to take it again. We waste time and at the end of the day they come up to me and say, 'What makes you so slow?'"

''So we went to the office of the studio manager [Julius Bernheim] and we had it out. 'All right,' he says to Julian, 'We'll run it on the screen and if it's no good, we'll take it again.'

'Well, we didn't take it again.'

Phantom's shooting schedule dragged on for 10 miserable weeks. The majority of Chaney's scenes were completed by mid-November and Julian moved on to lengthy excerpts from the opera Faust, exterior garden scenes, night exteriors of the mob, and assorted pick-ups.

By the time principal photography wrapped, just before the new year, Julian had exposed 350,000 feet of negative.

Universal had more than $500,000 invested in Phantom thus far, and though only half of what the studio had poured into Foolish Wives in 1922, it was considerably more than the $390,000 expended on Merry-Go-Round. Phantom was really an extraordinary proposition for a studio like Universal, where five-reel westerns were routinely made in two weeks on budgets of $12,000.

Technicolor, superior to the intended Prizma process, had been utilized to reproduce the spectacle of the elaborate sets and costumes in the finest natural color process available. The Masked Ball, the Faust excerpts, the ballet interludes, and all action on the Grand Staircase and in the auditorium had been filmed with Technicolor's two-color-system cameras under the supervision of Edward Estabrook.

With only the simple expediencies of editing and titling remaining, Universal booked The Phantom of the Opera into the Globe Theater in New York City for a February opening and sent the publicity mill into higher gear. Two of the largest electric light signs on Broadway heralded the event. Red Phantoms were lurking on otherwise blank billboards all over New York. Carl Laemmle had already given two public addresses about The Phantom which were heard by thousands over that new marvel of the age, radio. Laemmle's weekly column in The Saturday Evening Post began building the picture up, week by week.

Film editor Gilmore Walker had been preparing an assembly of the footage all through production and now he worked down to a rough cut of 22 reels. Based on the projection speed at which Phantom would ultimately be shown, (14 minutes per 1,000 feet) the rough cut lasted nearly four hours. Walker was instructed to bring the picture in at 12 reels — the same length Hunchback had been in its roadshow engagements, and the outside limit of acceptability. Theater owners were not pleased with any picture running beyond two hours as it cut down the number of daily showings, reducing the daily dollar take. Walker actually reduced the film to 10 reels.

Title writer Walter Anthony was assisted by Benjamin de Casserres. Formerly with Paramount's scenario department in New York, de Casserres had been brought out to Hollywood in November specifically to work on Phantom. He and Anthony now refined the titles and on January 6, 1925, a list of 159 temporary titles and inserts was presented to Julian, along with the billing sheet, for his approval prior to shooting and insertion into the negative.

The film included numerous inserts, notes from Christine to Raoul, and notes from the Opera Ghost to the managers. It was suggested that Mrs. Sterke in the publicity department write out Christine's letters. Special stationery was commissioned from Ralph Slosser for the Phantom's messages and Jack Lawton was chosen to write the Phantom's script in red ink on the black-bordered paper, as these were to be photographed in Technicolor.

With the New York opening mere weeks away, Universal decided to preview the picture in Los Angeles to learn what a paying audience thought of it. Exhibitor Sid Graumann arranged the preview in one of his theaters in January.

The preview was a disaster. The audience had been given cards on which they were asked to write down their reactions. The cards were unanimously of one opinion: “There's too much spook melodrama. Put in some gags to relieve the tension." Cautiously, a second preview was arranged but the audience response was no better.

The front office probably felt vindicated, because Julian and Chaney had delivered a film that was stronger on the uncommercial qualities of mystery and horror than the tried-and-true romance they knew their public wanted. With a $500,000 investment at stake, Universal could not release The Phantom of the Opera in its current form. Quietly, with no fanfare, the picture was dropped from all active publicity and shelved while the studio reviewed what to do.

By March, a memo to the New York office pretty well summed up the discontent with the film: “The Persian floats in and out the picture without rhyme or reason. He seems at first a sinister figure, and one surmises him to be an agent of the Phantom. The ending is not logical or convincing. A monster, such as the phantom, the official torturer, etc., and who delighted in crime could not have been redeemed through a woman's kiss, nor could a girl who had witnessed his diabolical acts have been moved to kiss him merely because he drooped his head sadly. His death rang false, moreover. Better to have kept him a devil to the end."

Julian had recanted on the arbitrary chase ending and restored the tone of Leroux's closing. Christine agreed to wed Erik to save her lover, bestowing her fateful kiss on his forehead. Overcome with his own hideousness and the purity of the girl, the Phantom expired majestically at the keyboard of his organ, pumping out the strains of his requiem, Don Juan Triumphant. During this, the action of Simon's mob parallel-cut to Raoul and the Persian in the torture chamber. Storming the Opera House, the mob worked their way to the cellars and arrived in the Phantom's lair in time to find him slumped lifeless at the organ. Simon gazed down in satisfaction at the body of his brother's killer while the lovers embraced.

Whether Rupert Julian washed his hands of the matter or was excommunicated, he had nothing further to do with The Phantom and his brief tenure as Universal's star director was over.

Would-be saviors stepped in and The Phantom of the Opera was put back into production with a new script that would deliver exactly what the front office knew their audience wanted: a movie about the love life of Christine Daae. Phantom was immediately rushed back into production. No more "Super Jewel" nonsense now, it would be salvaged by the Hoot Gibson western unit, those team-players who kept the Universal machine solvent, those journeymen who turned out 5-reel pictures in two weeks for $12,000; there would be no point in pouring good money after bad, at least not much good money. Edward Sedgwick directed the new material.

The new, improved Phantom received its world premiere a month later in San Francisco, and while the studio put a good face on things it was an even worse calamity. The picture would be shelved again, more heads would roll, and another six months of second-guessing and tinkering would pass before The Phantom of the Opera would be given a clean bill of health.

But that is another story.

Scott MacQueen's book Unmasking the Opera Ghost: The Making and Unmaking of The Phantom of the Opera further clarifies the imbroglio surrounding this classic film.

The author wishes to especially thank Rudy Behlmer, Kevin Brownlow, Robert Gitt and Richard Koszarski for their invaluable contributions. Also: Ronald V. Borst, G. Michael Dobbs, John Foster, John Gallagher, William Littman, Phillip J. Reilly, George Turner; Christine Kreuger of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences; and Peter Comandini and Richard Dayton of YCM Laboratories.

For access to more than 100 years of American Cinematographer reporting, subscribers can visit the AC Archive. Not a subscriber? Do it today.