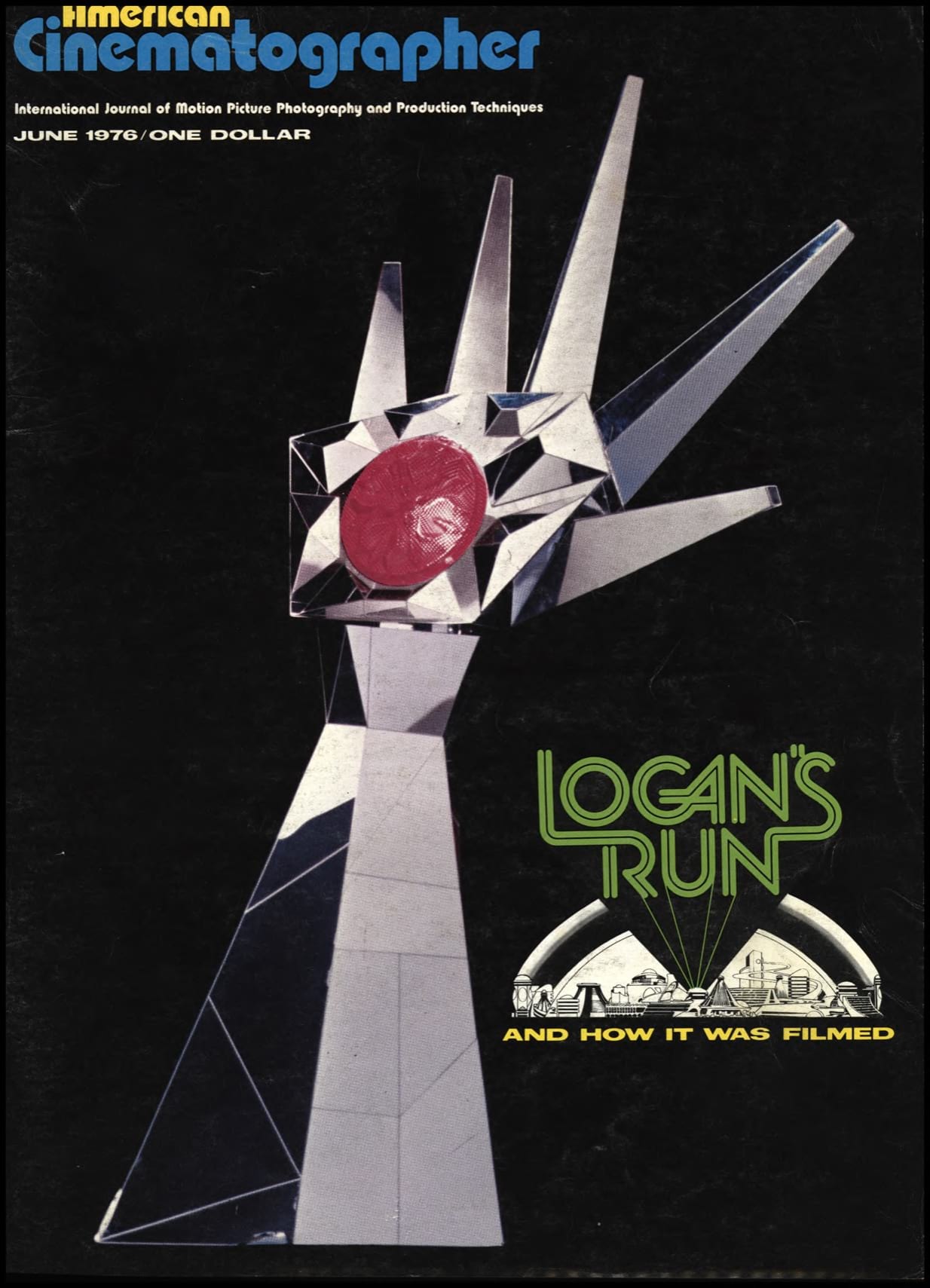

Photographing Logan’s Run With Ernest Laszlo, ASC

After having moved a camera through the organs of the human body, the famed cinematographer thinks nothing of moving it through the bizarre situations he encounters in the 23rd century.

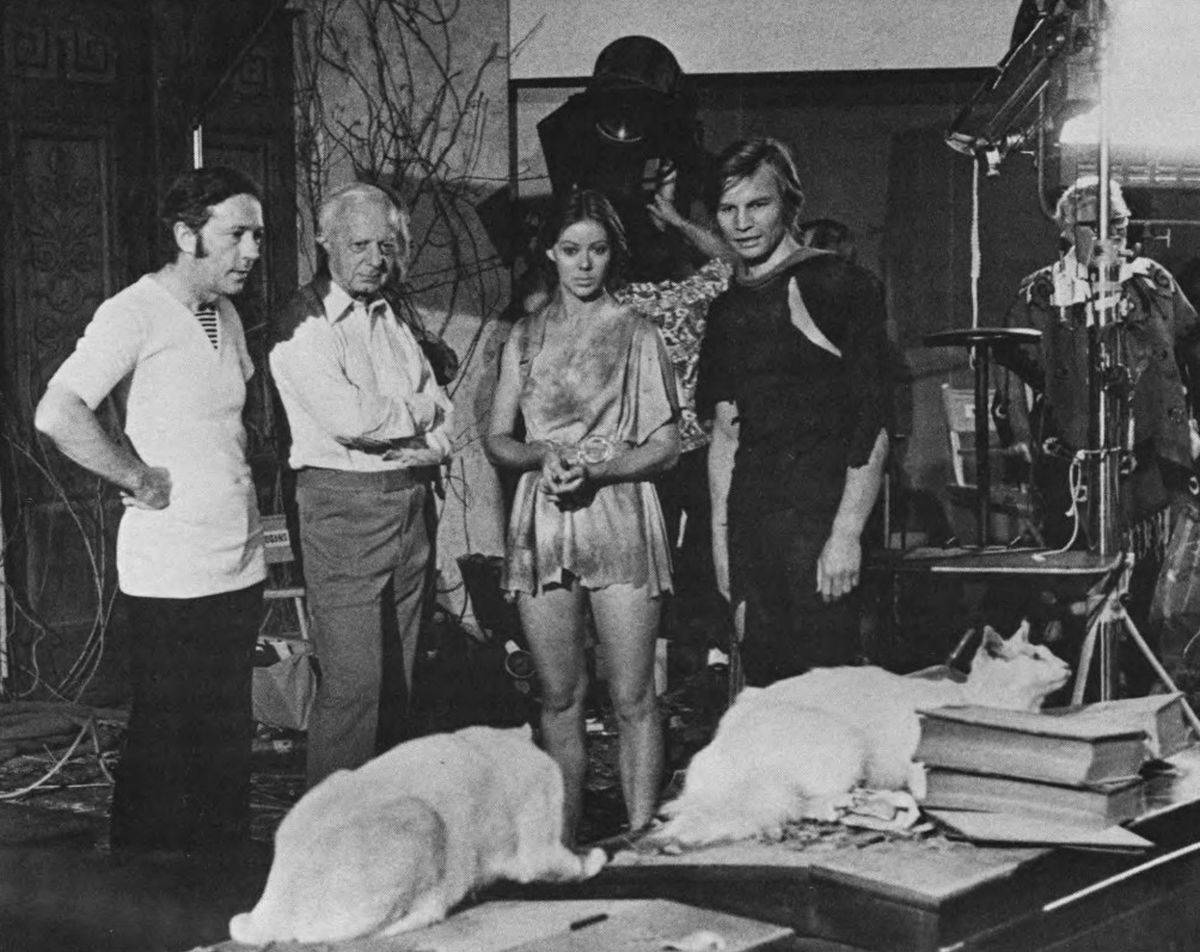

Recording on film the atmosphere of a civilization predicated to exist 300 years in the future is a tall order. To do just that, MGM assembled for the production of Logan’s Run a team of Hollywood’s most highly skilled technicians, men of long experience and incomparable expertise.

Such a project requires not only artists and craftsmen with a vast fund of technical knowledge to draw from, but people who are willing to “jump off into the unknown”, so to speak, tackling problems the solutions to which have no precedents — people whose imaginations transcend the “tried and true” of the past.

Even among science-fiction films — which, by very definition, invariably break some new technical ground — Logan’s Run is a far-out project. There are those who will equate its dazzling impact with that of Stanley Kubrick’s stunning 2001: A Space Odyssey, and with good reason. But in certain respects it goes even beyond that landmark film classic.

For example, whereas 2001 started with current science-fact and extended it by technical logic 30 years into the future, Logan’s Run conjures a society 300 years hence and deals in ideals that extend far beyond present realities into a realm of pure and vivid imagination.

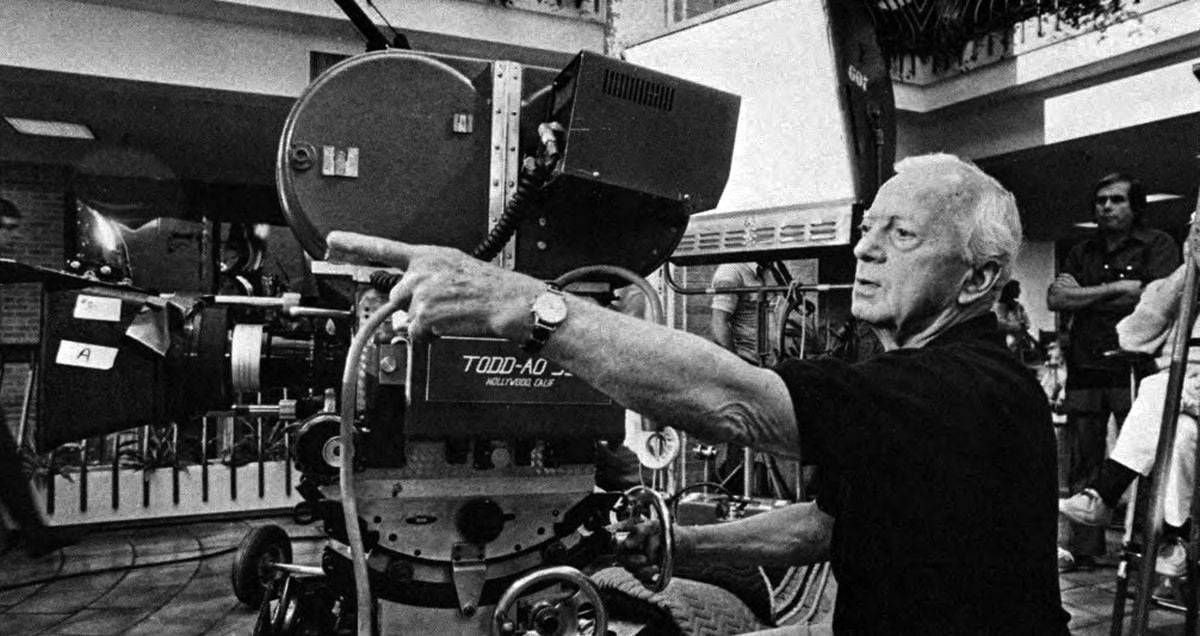

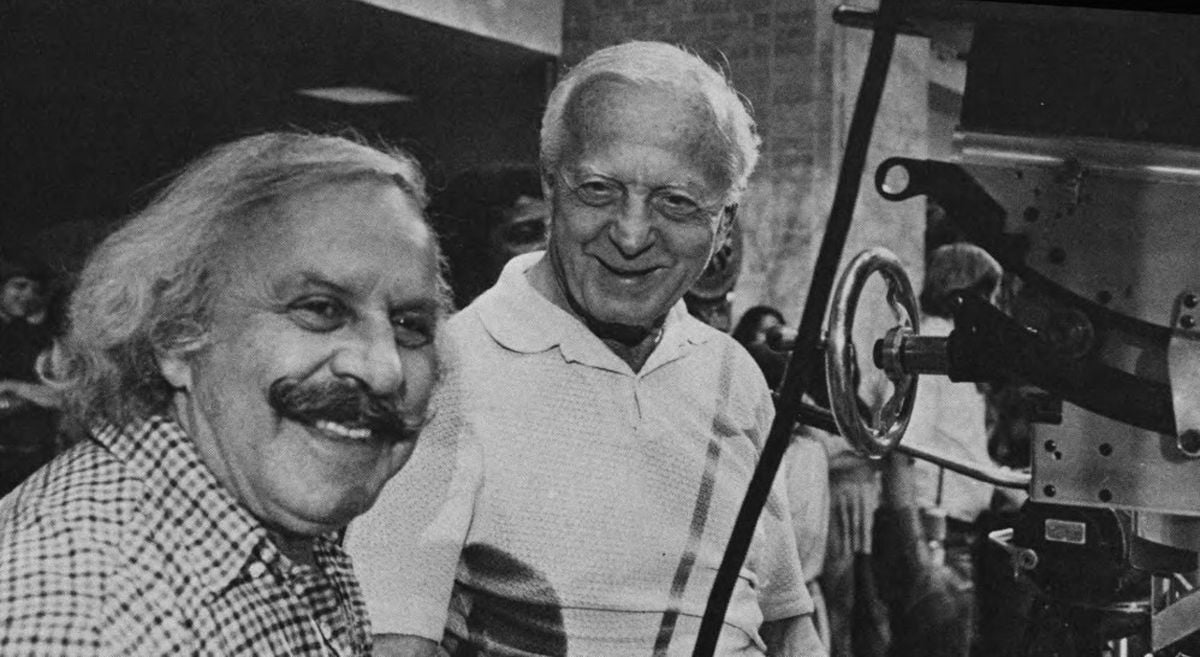

Where does one find a director of photography with the skill, imagination and sense of adventure required for such a project? Fortunately, Logan’s Run Producer Saul David didn’t have to look very far, because he had worked with ace cinematographer Ernest Laszlo, ASC on the filming of his wildly imaginative Fantastic Voyage a decade ago and had found that gentleman superbly capable of moving his camera through the arteries and capillaries (to say nothing of the heart and lungs) of the human body.

Add to that the fact that Laszlo is a classically trained veteran whose expertise is solidly founded on many years as assistant cameraman, operator and, since 1944, first AC. His credits are far too numerous to list completely, but they include such outstanding productions as Judgement at Nuremberg, It's A Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World, Ship of Fools (for which he won the “Best Achievement in Cinematography” Academy Award) and Airport.

During his lengthy career as one of Hollywood’s top cinematographers there is almost no technical problem which Mr. Laszlo has not encountered — and solved, but he welcomed the opportunity of striking off into new and unexplored creative territory that Logan’s Run offered. Of the experience, he says: “During my entire career I’ve never worked so hard on a picture.” But he also found it a thoroughly exhilarating adventure.

American Cinematographer: Can you give me a bit of background regarding your assignment to photograph Logan’s Run?

Ernest Laszlo, ASC: Well, of course, I’d worked with the producer, Saul David, before on Fantastic Voyage, which turned out very successfully. So, when Mr. David gave me the script of this picture to read I could tell that it was going to be an exciting project — quite unique in many ways and extremely challenging. Since I love a challenge, I looked forward to working on it.

What sort of pre-production schedule did you have in order to plan your shooting?

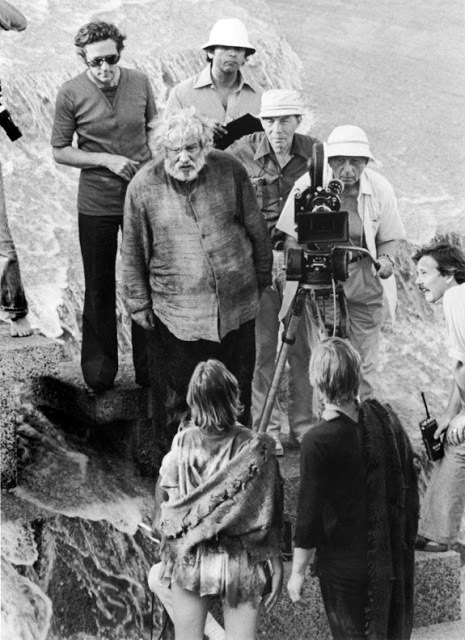

Very little. I went to Texas twice to scout locations and make a final selection of the shooting sites we would be using. I came back on a Sunday and we started shooting in Dallas the following Wednesday — so you might say that I had two days of preparation. It was like that all the way through the production. Perhaps because the sets were so intricate and took so long to build, I usually didn’t see any of them until a day or two before we were scheduled to shoot there — so everything was a big surprise. One of the things I liked so much about working with Stanley Kramer was that he always had his sets built a month ahead of time and he and I would take a script and plan our every shot right in the sets. That was a luxury we didn’t have on Logan’s Run.

How would you describe the photographic style which you employed in shooting Logan’s Run?

There were actually two styles — one for the action that takes place within the Domed City, and quite a different style for the sequences shot outside the domes in natural sunlight. Inside the city the light is supposedly filtered and diffused by the translucent domes and the interiors are lighted from subdued artificial sources. So in photographing those sequences I had to use — not necessarily an extremely soft quality of light, but nothing harsh. On the other hand, once the characters leave the city and get out from under the domes, the quality of the light becomes harder and sharper, with somewhat less fill. This made for an effective visual contrast between the controlled, protected environment in which they lived and the raw “real” world they experienced when they got outside.

What would you say was your most challenging lighting problem on this picture?

The most difficult problem was lighting those vast buildings in Texas. The Great Hall in Dallas, for example, was longer than two football fields. It was such a tremendous area that I had to use 9,000 amps to light it — which required bringing in a special transformer. Hiding the lights was also a big problem, but there were a few large pillars that helped that situation. The place was so big that, even with 9,000 amps, I still had to force the film one stop in development.

Did you use a daylight balance in there, or were you shooting strictly with incandescent light?

We had both types of sequences. For daylight we could let some outside light come in and augment it with arcs, but for night sequences we used incandescent light and had to black out the skylights — which was quite a job.

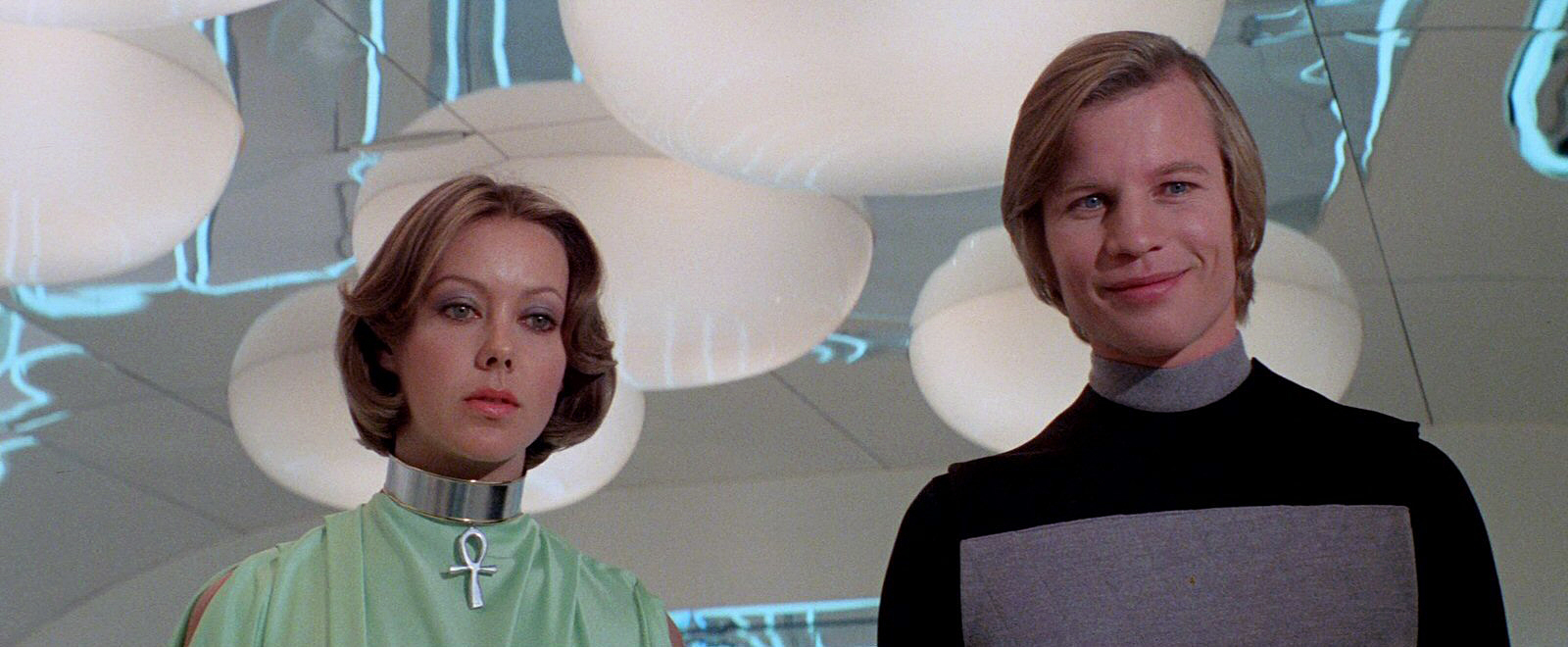

Many of the sets in Logan’s Run have large mirrored areas and highly reflective surfaces. What kind of problems did that cause?

In the Atrium, which is a very large structure, almost everything is mirrors or highly reflective metal. I think I spent more time getting the lights out of those mirrors than actually lighting the place, but I must say that it was worth it. The result is very effective. It looks great.

Did you use much colored light in shooting?

There’s one sequence where I used it quite a bit, along with some other exotic lighting techniques. Logan and Jessica go into the Love Shop, where “free love” is the activity. Everybody is naked and so, most of the time, the lighting is kept quite low. We shot that in a private nightclub in Dallas called “Oz." We were shooting in there for three days and it was some job to light. Each lamp had to be hung separately and it was difficult to hide them. As I said, most of the time the light was kept low, but every now and then we would flash a bright light for effect, but not long enough to accentuate the nudity. In addition to colored light, we also used black light in there.

Black light — or UV light — has its own set of problems, doesn’t it?

Yes. In the first place, it’s not very bright and you really have to pour it in there and shoot wide open or you won’t get anything. You wouldn’t dare stop down. Secondly, because of its peculiar wavelength, it’s very difficult to get any sharpness with black light. We used it also in the Sandman headquarters. There’s another interesting sidelight about shooting the Love Shop sequence. Saul David especially wanted this to be something dreamy and beautiful and in good taste, so he hired a ballet master to choreograph the action. Then we shot it at 48 frames to accentuate the dreamy effect.

Can you tell me about shooting in the ice cavern set?

Well, it was an extremely beautiful set. Dale Hennesy did a wonderful job in designing it, but by its very nature, it had some unique built-in problems. First of all, I didn’t dare use anything like flat light in there because, in order to bring out the texture of the ice and snow, cross light was the only thing to use. However, again, there was no place to hide the lights. I had no choice but to chop a few holes in the ceiling and put lamps in so that I could get the required cross light. It was a shame to have to do that, even though we patched up the holes afterward. I must say that Dale was most cooperative when it came to any changes like that which I needed to have made. He and I were on Fantastic Voyage together and we’re old friends, so we work together very closely and very well.

Did you get an opportunity to do much low-key lighting in the picture?

In addition to the Love Shop sequence, which was certainly low key most of the time, there was one other sequence that called for really low key lighting. The main part of the escape sequence takes place in what was formerly a sewage disposal plant in El Segundo. It has tremendously large pipes and we went very low key there because the menacing mood of the sequence demanded it. You always have to adapt your lighting style to the set and to the mood required in the sequence.

Did you shoot any actual exterior night shots?

There’s a single night scene which we shot at the Water Gardens in Fort Worth. It’s part of the sequence in which they return to the city after having been outside and that entire action happens at night. The night scene at the Water Gardens wasn’t easy to shoot, but it turned out beautifully.

With the enormous amount of special effects in this picture you must have had to work very closely with Bill Abbott [ASC].

Yes, I did. I must say that it was a joy to work with Bill. He’s a very wonderful person, very understanding, and I did my very best to cooperate with him. He was with us on Fantastic Voyage also, and we have a wonderful relationship that works to our mutual benefit.

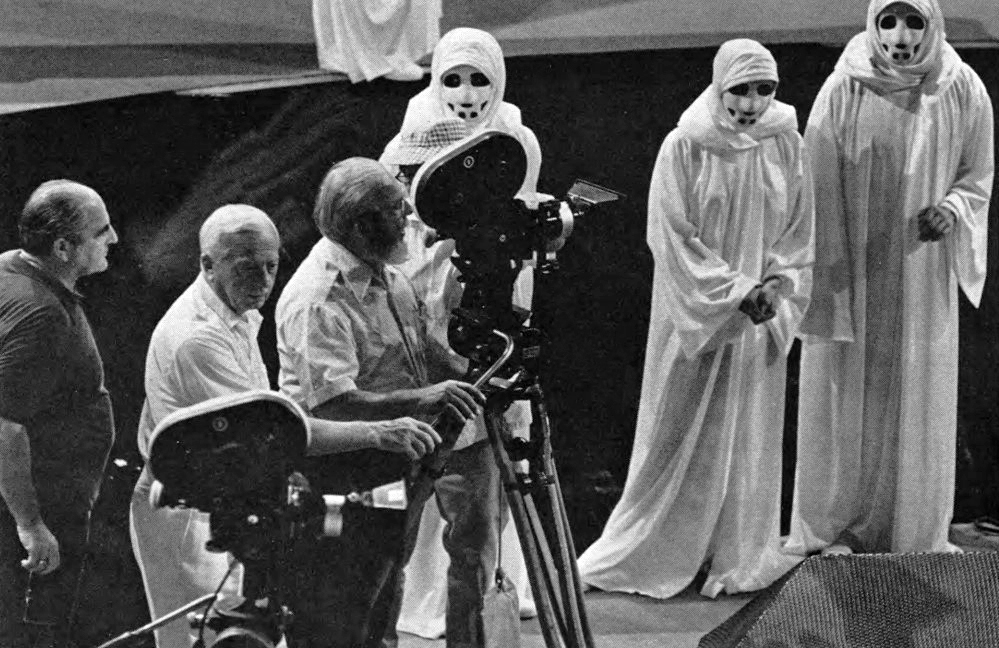

Tell me about the Carousel sequence.

Well, of course, that was the big one, technically speaking. They built this marvelous set, an arena seating several hundred people, with the big turntable in the middle and all the people flying up to the ceiling. My main problem was that I couldn’t get back far enough to get a full shot of it with the lens we had available. So Saul David called Dr. Richard Vetter at Todd-AO and he came over to consult on the problem. It just so happened that they had been working on the development of an extreme wide-angle lens. It was in prototype form and hadn’t actually been completed, but they let us use it for that sequence and it saved our necks.

Can you tell me the technical characteristics of that lens?

It’s an 18mm, T/1.7 lens that covers a field of about 120 degrees — which, I believe, makes it just about the widest-angle anamorphic lens in the world. Another good thing is that it’s relatively distortion-free. While there is some barrel-distortion to the lens, the fact that the arena was round made it completely unnoticeable. The only further problem was that we wanted to cover that sequence with two cameras — once shooting down and the other shooting up — but Todd-AO didn’t have another 18mm lens. However, they did have a prototype of a 24mm, T/2.3 lens which they also let us use. Between those two lenses we were able to get everything we wanted. The Todd-AO people were marvelously cooperative all the way through the filming.

death masks. After a short initial period, cast and crew members working on the film suspended disbelief and began to accept the screenplay’s bizarre elements as reality — an attitude which resulted in an atmosphere of greatly enhanced realism on the screen.

Did you use any special filter effects in shooting Logan's Run?

Yes. There were some special filters which Robert Wise had made up especially when he was doing The Sound of Music. They’re the only filters of their kind and they cost about $300. each. Bob has two of them and he was kind enough to lend them to me for Fantastic Voyage, so I borrowed them again for this picture. I used them in a couple of sequences, but mainly for shooting the Carousel. They seem to be a combination of diffusion and star filter and they were very helpful, not only in adding sparkle to the crystals in the sequence, but also in helping to hide the wires used to fly the people — which is always a big problem. I’m very grateful to Bob for making them available to me.

Can you tell me about the video viewfinder that you had on the camera during shooting?

It’s very helpful in that you can check the action immediately instead of having to wait for dailies to see if you got what you wanted, but it is mostly a tool for the director. It’s helpful in checking composition, but other than that, it doesn’t aid the cameraman very much. The image is in black-and-white and isn’t precise enough to really tell you how the lighting is registering. An added disadvantage, in my opinion, is that the actors always want to have a look at the last take, and that can hold things up.

Can you think of anything I haven’t asked you that you’d like to talk about?

No, but I would just like to give credit to my wonderful crew. They work with me all the time and they’re very enthusiastic — even under the difficult conditions we had in Texas. We were working a six-day week from early morning until late every day, and some of them had to spend their Sundays cabling, without a day off. They’re a marvelous team and I just love working with them.

You’ll find our complete visuals effects story here. And additional details on the production here.

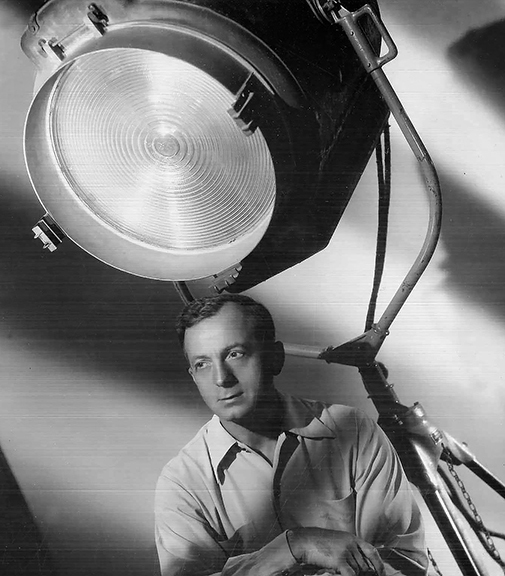

About the Cinematographer

Ernest Laszlo, ASC was born on April 23, 1898, in Budapest, Hungary. He emigrated to the U.S. and began working in Hollywood as a camera assistant and then operator at Paramount, collaborating with ASC cinematographers on major projects, including Wings (1927; for Harry Perry), The Right to Love (1930; for Charles B. Lang) and Huckleberry Finn (1931; for David Abel). He also helped film the Technicolor sequence for Howard Hughes’ Hell’s Angels (1930).

Meanwhile, Laszlo also worked on low-budget productions at other companies as a director of photography, including The Pace That Kills (1928; his first credit), The White Outlaw (1929) and The Primrose Path (1931).

His first major studio credit was Paramount’s sensationalistic The Hitler Gang (1944), and, before his retirement in 1977, Laszlo would photograph 69 features, becoming well known for his frequent collaboration with directors Robert Aldrich and Stanley Kramer.

Aldrich, impressed by the cinematographer’s lighting in the noir classic D.O.A. (1949; directed by Rudy Maté, ASC), tapped him for such hard-edged pictures as Apache (1954), Vera Cruz (1954), Kiss Me Deadly (1955), The Big Knife (1955), Ten Seconds to Hell (1959) and The Last Sunset (1961).

Laszlo and Kramer first worked together on the courtroom drama Inherit the Wind (1960), for which the cinematographer earned his first Academy Award nomination. They followed with Judgment at Nuremberg (1961; another nomination), It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World (1963; also nominated) and Ship of Fools (1965; for which Laszlo won the Oscar).

More Oscar nominations for the cinematographer came for Fantastic Voyage (1966), Star! (1968), Airport (1970) and Logan’s Run (1976).

He died on January 6, 1984.