Primal Urges Propel Basic Instinct

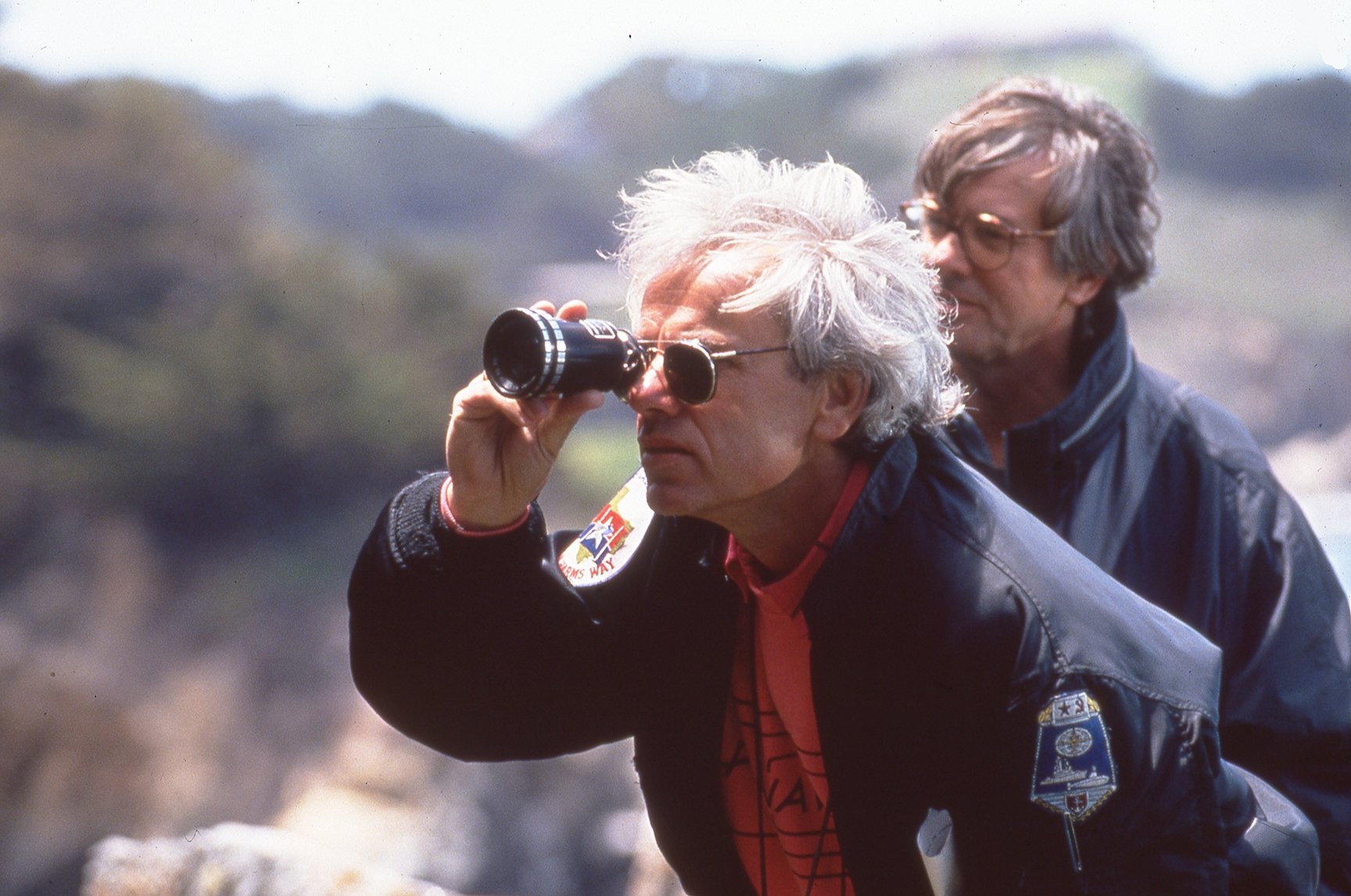

Cinematographer Jan de Bont, ASC and long-time collaborator director Paul Verhoeven re-team for a sadomasochistic murder mystery.

This in-depth look at the making of Basic Instinct first appeared in American Cinematographer's April 1992 issue. For full access to our archive, which includes more than 105 years of essential motion-picture production coverage, become a subscriber today.

When director Paul Verhoeven invited longtime collaborator Jan de Bont, ASC to join him on his latest feature, the cinematographer quickly accepted. “I hadn’t done a dramatic thriller for many years,” says de Bont, who teamed with Verhoeven on Turkish Delight, The Fourth Man, and Flesh and Blood, among other pictures. “Most of the pictures I’ve shot in the last five years have been action-oriented, surrealistic or science fiction, but nothing in which drama plays a major part. This was the most interesting reason for me to work on Basic Instinct.

“It is a film noir, but it’s not noir that much. We always wanted it to be more white than black.”

— Paul Verhoeven

“The second reason was that I hadn’t worked with Paul for a long time,” he continues. “We grew up in Holland together. I did his first, second, and third movies. Flesh and Blood was our last feature together; it was his first English language picture, shot in Spain in ‘85. I’ve been waiting for this time because we work very closely together. I know instantly what he wants, what he needs. He can trust my suggestions. Everything works very, very smoothly.”

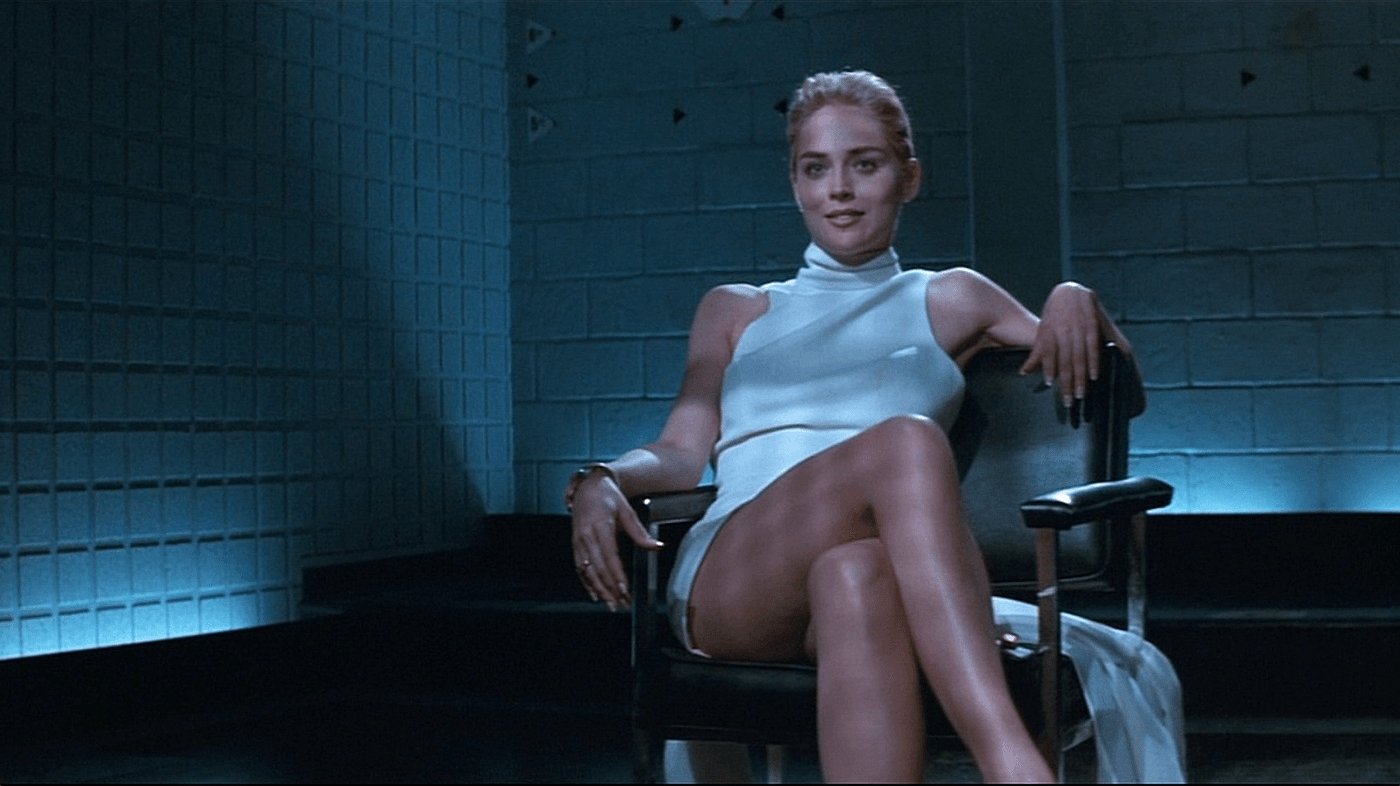

De Bont suggested early on that the picture’s style must be audacious. Verhoeven, whose credits also include the popular sci-fi thrillers RoboCop [covered in this AC Podcast and AC, July 1988] and Total Recall [AC, July 1990], describes his new film as “a sadomasochistic murder mystery. It is a film noir, but it’s not noir that much. We always wanted it to be more white than black.”

Production designer Terence Marsh, a two-time Oscar winner (for Doctor Zhivago and Oliver!), noted that although it was decided early on that Basic Instinct would have strong film noir elements, “we tried to give it abundant sunlight and color and to let the story tell the terrible things going on behind this idyllic facade of beach houses and oceans.”

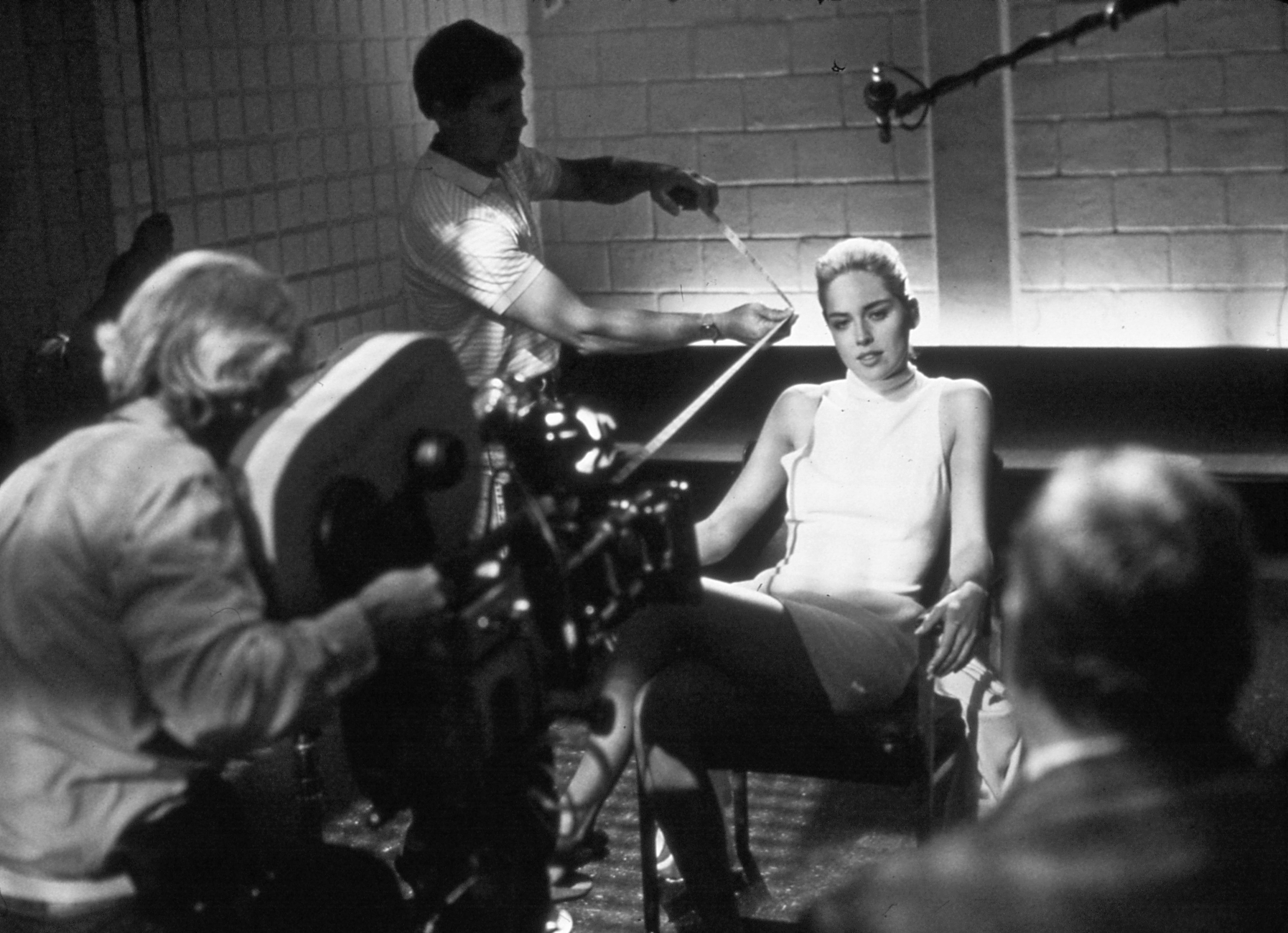

Set in San Francisco and filmed on location there for half of its 70-day schedule, Basic Instinct also shot amidst the lush oceanside serenity of Monterey, California. About 35 shooting days were spent on the Warner Hollywood lot, where a number of elaborate exteriors and interiors were built, including a good portion of the San Francisco Hall of Justice.

It’s doubtful that San Francisco has ever seen the operatic scale of shooting required for the picture’s climactic, unconventional car crash at Moscone Center. In the grand Hitchcock style of going to great lengths to avoid cliché — in this case the temptation to run chase scenes up and down the famous hills overlooking the Bay — Verhoeven, de Bont, and company launched a Lotus over the edge of a large hotel construction pit, against a nocturnal urban backdrop of Wagnerian proportions.

That sequence notwithstanding, the filmmakers’ audacity is perhaps best seen in the scenes shot on one of the larger stages on the Warner Hollywood lot, Sound Stage 6. There, Marsh built an opulent discotheque (set in a church, no less) to rival any in recent screen memory.

In one of Basic Instinct’s most elaborately staged sequences, actors Sharon Stone, Leilani Sarelle, and Michael Douglas ogle and claw each other to gut-wrenching, tribal disco sounds amid a pulsating sea of 400 extras. To achieve maximum realism, Verhoeven insisted that the disco sound system be top-of-the-line hardware, not simulated cue music; the cast and crew found that earplugs did little to relieve the pain.

“Nightclubs these days are pretty wild. It’s a very hellish world if you’re not familiar with it. I wanted it to be rougher, more shocking...”

— Jan de Bont, ASC

The tableau’s religious overtones add a surreal touch: colorful stained-glass windows adorn every wall and waiters dressed in somber clerical garb with ebony crosses around their necks meander among the dazed dancers. Above the five-foot-high disco speakers, two scantily-clad dancers twist, gyrate and tear at their own muscles. A full-size crucifix hangs at the opposite end of the dance hall, while the parallel walls of the disco glow with magenta and cyan neons. The ceiling of the set was covered with 180 tungsten Leko ellipsoidal reflector spotlights aimed toward the dancers at 45-degree angles.

At eye-level, Steadicam operator Larry McConkey pursued the trio as they vanished and reappeared in the crowd. McConkey shot both objective and subjective shots of the characters moving in and out of each other’s range: Douglas groping to make contact with Stone, Stone missing Douglas.

Twenty-five feet above camera and operator, a hydraulically-mounted mast protruded from a ceiling mount. The attached boom arms held a grid of 70 tungsten six-volt PAR 36s (GE 4515). From a nest higher in the ceiling, two operators controlled movement of the grid via remote. Powered by a servo-motor, the so-called Robotic Light Grid (RLG) moves on command in four directions: up and down (mast), rotationally (mast), rotationally parallel to the floor (grid itself), and rotationally perpendicular to the floor (grid).

De Bont recalls that in early production meetings with Verhoeven and Marsh, “[the RLG] was one of the first things I mentioned when I read the script. I hadn’t seen the location yet, and wasn’t aware that we were going to use a church as a site for a disco, but I felt that the sexual tension that exists between the two women and between Michael [Douglas’s character] and Sharon [Stone’s character] needed some extra power. I wanted an eye or light of God to shine on them, to select them out of the crowd.”

Despite his penchant for things futuristic, Verhoeven at first had some reservations about his cinematographer’s idea. “The construction is a big piece of metal hardware and without lights it seemed to be intruding,” he says. “But when all the lights were on you would only look at the lights, so it was fine.”

Cost was also a factor: the RLG added between $50,000 and $75,000 to the budget. “We decided to use these lights because there are not many bright, narrow-beamed tungsten lights available,” notes de Bont. “Most are daylight, such as HMI or CDI lights, which give a very blue light. I wanted to have a tungsten white light which I could use at night, which was very powerful, as powerful as an arc or more powerful — narrow-beamed and still controllable without consuming a great deal of amperage.”

De Bont asked special effects coordinator John Frazier to build a 4’ x 6’ mobile metal lattice which became the RLG, and was pleased with the results. The narrow-beamed units produced just the effect de Bont was after — “a very short flare that [lasts only] for a few frames, then disappears again and keeps the actors visible without disturbing the audience with the light effect.

“That's what I like about the special effects guys,” he adds. “They make it exactly to specs and it works.”

De Bont explains the disco’s lighting design: “Normally in nightclubs you’d employ multicolor lighting: green and blue lasers and follow spots, which change colors continuously. I didn’t like that at all. I wanted it to be just like the colors from stained glass, strengthened by the neon, to give a religious motif. Everything else was bathed in almost pure white light, very modern, cool, harsh light coming from the Lekos and the grid.”

At the same time, the deep-hued neon wall fixtures threw off enough ultraviolet light to make his backgrounds go a “hellish” dark blue. Flooding the set with 250 footcandles and filming at T5.6 on Eastman EXR 500T 5296 color negative, de Bont sought to produce a contrasty, high-density negative. The superabundance of light on the set was somewhat deceptive since the main source — the 180 overhead Lekos — served the dual purpose of dressing the set and lighting the actors.

De Bont had another equally important reason for achieving a denser negative: “I found out that it’s one thing to have good dailies and another to have a good release print.” Higher lens stops and higher negatives mean higher print numbers, usually around 40, allowing him to get higher release prints later on.

“In general, when you have dense negatives you have the best chance to get a very high-quality release print because [normally] you have to go through so many stages to get there — you have to make your interpositive, internegative, etc. By doing all those different steps, you lose not only quality but blacks as well.

“If you have a thin negative, it gets gray and murky. The brilliance and the color disappear as well. With a denser negative you can get release prints that are very close to your original. This means there are times you've got to use a little bit more light than is normal. The result is a lot better, though.”

The color design of the rumbling disco set was only one of a complex series of elements used to illustrate the psychological, at times primal, drama. In seeking to evoke this tangle of emotions, de Bont introduced a powerful motion into his lighting design with the aid of a computer which regulated the Lekos, sending waves of light, along with the waves of music, over and through the crowd.

Above the hundreds of dancers the 180 Lekos went on and off in rapid sequence, moving in changing patterns and configurations and highlighting different parts of the crowd. The light patterns were controlled from one corner of the stage by operator Kent McFann, running a Jands Instinct Memory Control Board, which mimics and repeats the patterns of light the operator commands of it. It is not a computer and cannot be pre-programmed.

For a scene in which Michael Douglas enters the unfamiliar nightclub, de Bont and his technicians experimented with almost every imaginable combination of lighting chases to create a sense of danger.

“I wanted to make it look demonic, and I couldn’t get the right feeling because the chases I had built in the [controller] program were too cozy, too nice-looking. Nightclubs these days are pretty wild. It’s a very hellish world if you're not familiar with it. I wanted it to be rougher, more shocking to [Michael Douglas' character]. All of those things are subconscious; you’re not going to be aware of it one shot at a time, but once you see all the shots put together it’s going to help set the tone for that scene. So I was worried that it was not strong or violent enough.”

De Bont has grown accustomed to shooting in his favorite format, anamorphic. “I’ve done the last seven or eight movies in anamorphic; to me it’s the ideal format in the theater, and that’s how I always see my photographs framed. The 2:35 ratio reflects what you can see with the human eye. Any other format — 1:85 or widescreen — is too narrow, and cuts off all the information you get from the background that surrounds the actors.

“With this movie, we used Primo anamorphic lenses; Panavision has a set of Primo spherical lenses and they finally made an anamorphic set for me. They’re huge lenses and they weigh a ton, but they have incredible sharpness and color quality, and they’re great for the anamorphic format. What makes them special is an incredible increase in sharpness compared to any old C or E Series. Normally in wider lenses the detail falls apart and gets very fuzzy.

“The Primos also have much more depth of focus. You can put any backlight in them and they don’t flare out because the coating is very special on those lenses. There’s almost zero distortion, which is also why they’re so big, as big as any zoom lens.

“The set I use consists of 35, 40, 50, 75, and 100 mm — all T1.9 lenses. They also have a Primo zoom, but I don’t think it has the same quality as the prime lenses. I’m using virtually no zoom lenses on Basic Instinct.”

Despite the technical expertise de Bont brings to his cinematography, he feels a strong commitment to the humanity his films express. “Thrillers always tend to be on the cold side,” he points out. “People tend to film in a cool way anything that has to do with the darker side of society. I don’t like that. Even in scenes that have a very dark undertone, it’s nice to bring out the warmth of people, too.

“I quite often go against what you would expect. At one point in the scenes with Sharon in her home, the audience is going to suspect that she is the killer, and so are afraid of her. Although she is rich and lives in a lavish environment, I didn’t want to make it too warm. There I went the opposite way. You have to go with whatever the scene gives you; for this movie I had to use a lot of warmer tones because there were so many cold elements in it.

“I’m not limited to technical ways of filming,” he continues. “The technical part is the most unimportant and uninteresting part. I can film any scene that anyone wants shot but I still want to be able to interpret it and to add my sense of emotion or feeling to it. I’m trying to always be a spectator. I try to imagine how an audience would react to a scene when they see it finally on the screen, because that’s the only thing that really counts — not looking at beautiful dailies. And you can only do that with feelings and emotions.”

If you enjoy archival and retrospective articles on classic and influential films, you'll find more AC historical coverage here.

Unit photography by Ralph Nelson.