Tried-and-True Style for RoboCop

A look at the creation of the film’s mechanized nemesis, the ED-209 from Phil Tippett and company.

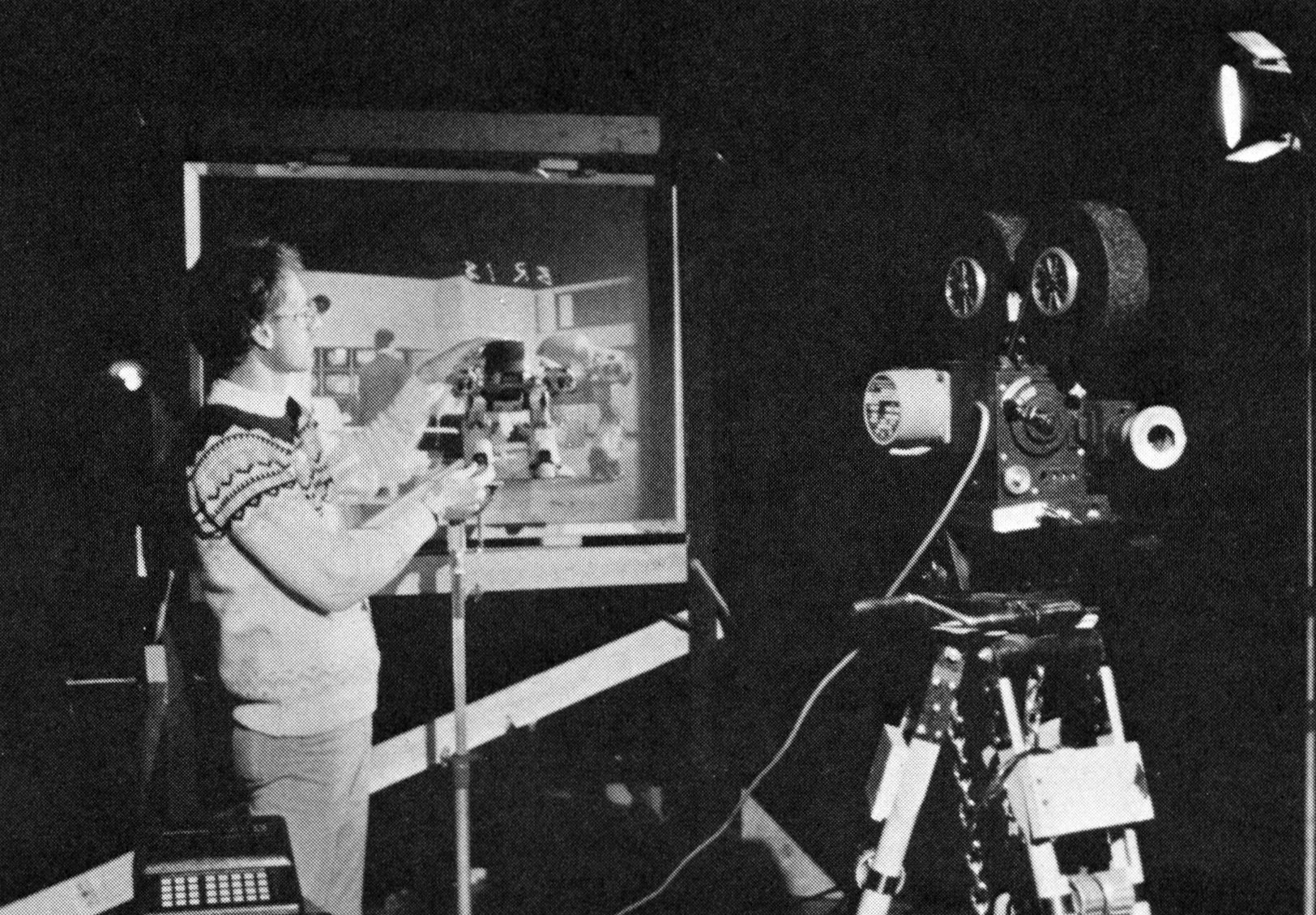

Phil Tippett's exceptional stop-motion animation work in the low-budget megahit RoboCop was a most welcome surprise to the visual effects assemblage of 1987. Working on an extremely tight budget and time schedule with long-term Industrial Light & Magic cronies Harry Walton, Randy Dutra and Tom St. Amand, Tippett managed to create the menacing character of RoboCop's nemesis, the ED-209 robot, in true quick and clean Ray Harryhausen style by animating his puppet against a rear screen-projected background, which saved on costly and time-consuming compositing.

Tippett emphasizes credit to director Paul Verhoeven, who insisted that each of the effects shots be incorporated into the film in the most dramatic way possible. The advantage Tippett's fast and spontaneous animation work for RoboCop has over the cleaner, more refined work of his competition is that every shot he made works entirely in the service of the story.

"You can do the best work in the world, but if it's in a bad film, who cares?" Tippett explains. "I would even go so far as to say you can do sub-standard work in the service of a good idea told with dynamic and kinetic filmmaking.

“The best thing about our work on RoboCop was that as a result of a stringent budget, we had to work very quickly and everything we did had to work the first time and that was it, we had to move on. It's a different way of working, but I think it's the real way of working. Special effects shots tend to be relegated to second-unit directors, but Paul stayed with us, making sure that every scene was shot with the right kind of dramatic impact. It's a different kind of sleight of hand. It's not the apogee of special effects work, but it is of moviemaking."

“Paul [Verhoeven] said, ‘If it’s not believable, if it’s not realistic, then it’ll be laughed off the screen.’”

Verhoeven's willingness to participate in a project called RoboCop inspired Tippett and his crew, who were fans of the Dutch cult director's other films, which include Spetters, Soldier Of Orange and The 4th Man. Verhoeven became a galvanizing force in the making of the film, inspiring everyone involved to do better work than the budget would allow "He was the guy who really made it all work," Tippett says admiringly, "because he made it clear that he wouldn't accept junk, which is all that we felt we could deliver since we were locked into such a low budget. Paul said, 'If it's not believable, if it's not realistic, then it'll be laughed off the screen."

To solve the paradox of getting great-looking effects onscreen with no money, Tippett reexamined the methods of stop-motion animation legend Ray Harryhausen, who has successfully balanced art and commerce in partnership with producer Charles Schneer for almost three decades. "It was quite clear to my producer, John Davidson, that there had to be a cheap way of doing these effects, so I looked at the films Ray Harryhausen did with Charles Schneer and I realized that they ran everything through one system, one mill, and that's how they got more shots for less money," Tippett recalls. "I began to see that the way to go was to use rearscreen-composited stop motion just as Harryhausen used to do all of his shots."

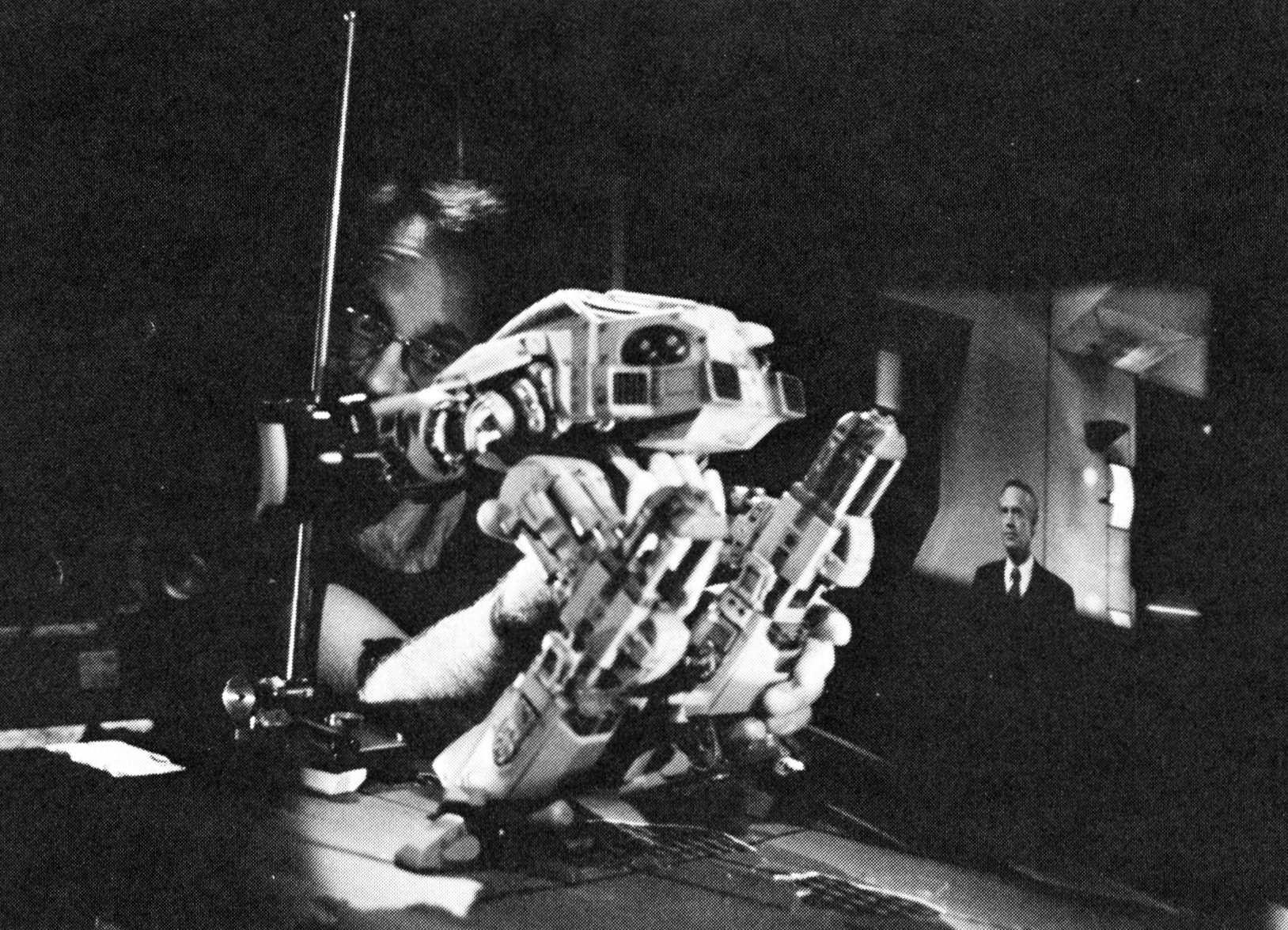

This technique, in which the stop-motion puppet is animated against a rear-projected background plate advanced one or two frames at a time, proved to be quite a time-saver, but it also had the disadvantage of limiting the director's choice of set-ups, because actors cannot cross in front of the puppet, they can only move behind it or off to one side. "Fortunately, Paul was willing to sit down with me and talk about what he wanted for each sequence. I started off by telling him all of the limitations of the rear screen stop motion process, and after about two hours of delineating all of what we couldn't do with it, we got involved in a more creative discussion about what we could do to overcome these limitations.

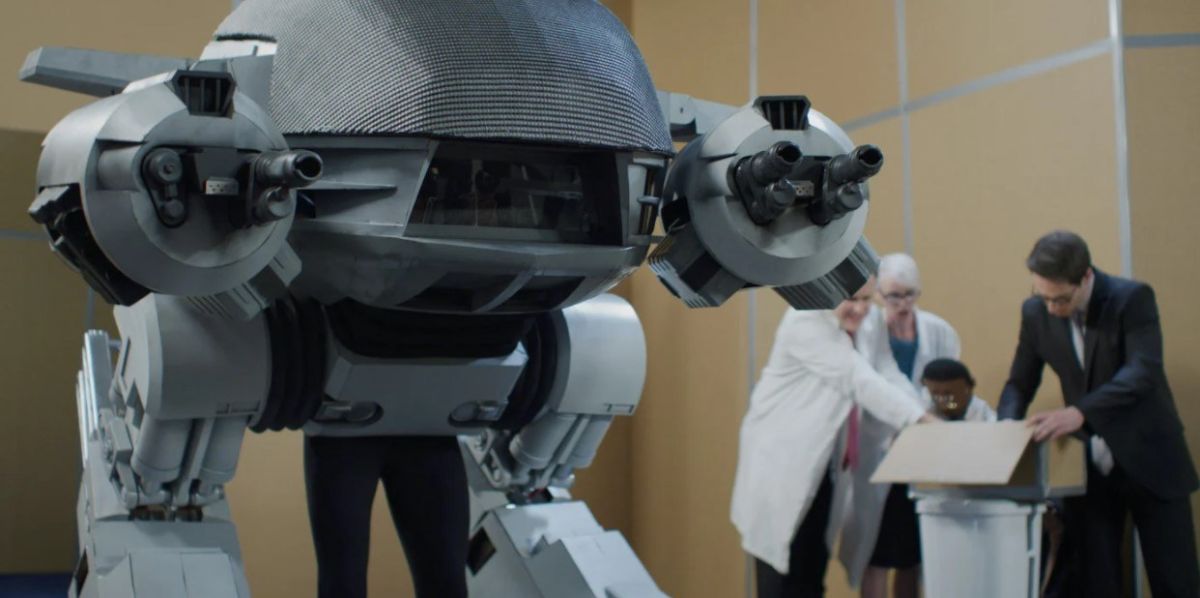

"From the beginning, we knew we needed a full-sized ED-209 figure, and that became something we realized could be used to our advantage in terms of the animation. The solution was simple: we used stop-motion for the ambulatory shots, but when we took the puppet to a power down situation where it would stop moving, we'd wheel in the full-sized prop so we could have extended dialogue scenes and handle difficult live mechanical effects like the rocket blasts with the actors standing in front of it."

“Unlike RoboCop, who was a man locked inside a metal body, ED-209 was very hard and mechanical, with the precision of a lathe and the physical force of a Mack truck.”

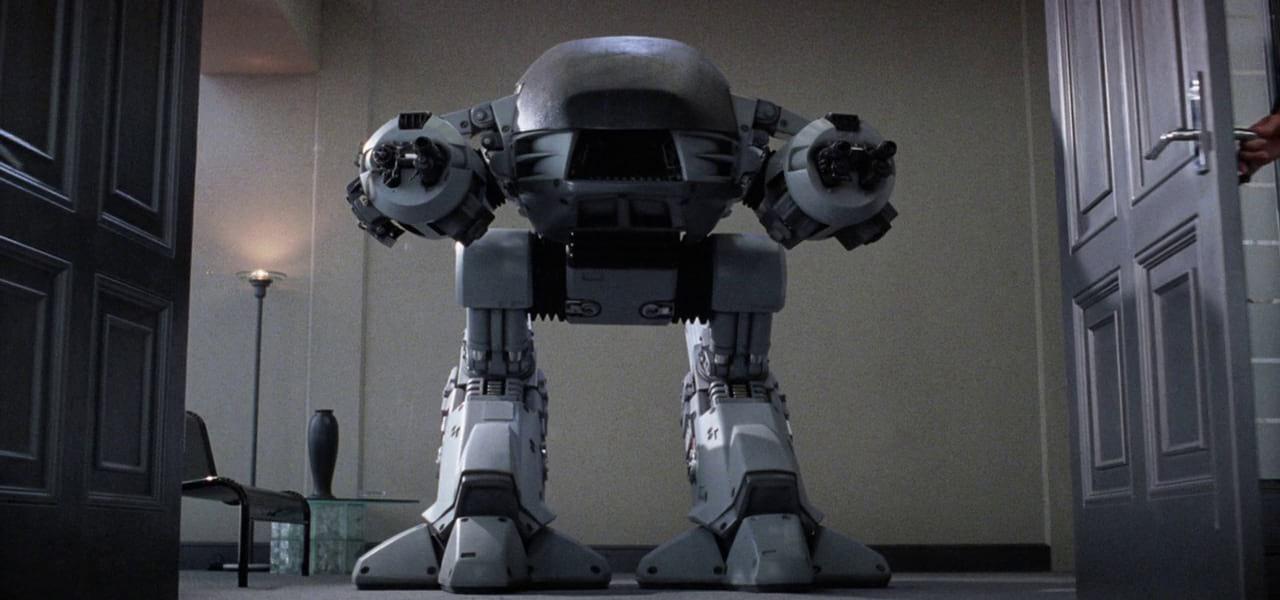

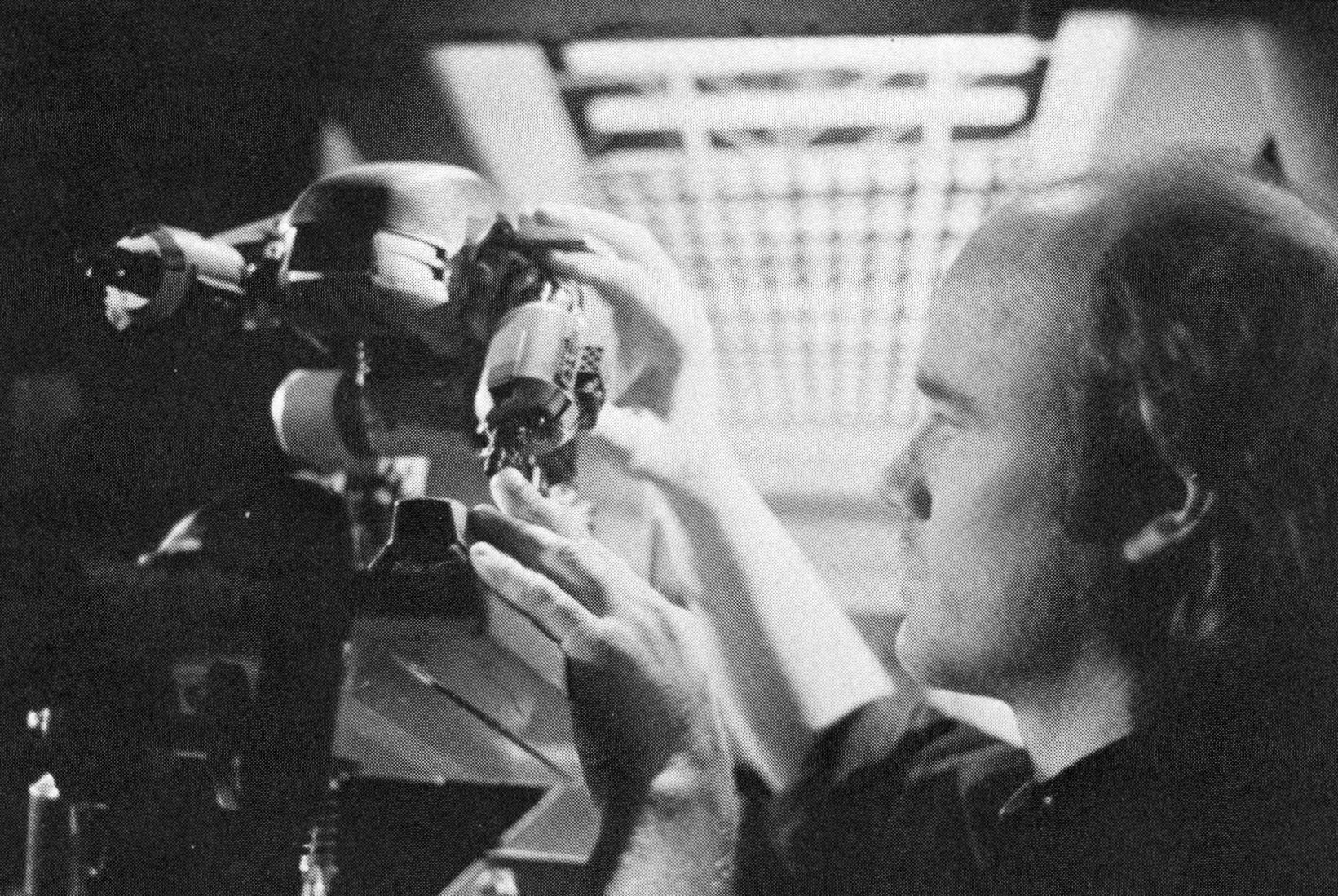

The man responsible for creating ED-209's "dumb but powerful" look was a talented 23-year-old named Craig Davies, who also built the full-sized prop and the outer shell of the stop-motion puppet. "Craig was singularly responsible for the look of ED-209," Tippett says. "I have absolutely no sensibility when it comes to designing mechanical things. Craig worked closely with Verhoeven, who made it clear from the beginning that he wanted something shaped like a 'Z.' He wanted something that was completely un-anthropomorphic; he wanted a character who was RoboCop's antithesis. Unlike RoboCop, who was a man locked inside a metal body, ED-209 was very hard and mechanical, with the precision of a lathe and the physical force of a Mack truck. Paul and Craig worked together to make ED harder and sharper while at the same time trying to make it feel like a real piece of hardware with certain design qualities that people would call sexy.

“ED-209 was a piece of junk designed to kill people, but the corporation realized they were also making something they had to sell to other people, so it had to look nice and have certain attractive qualities! At the same time, they wanted it to look as if it was still in the prototype stage, so it was painted a neutral gray color and covered with warning stickers. Paul was very keen that ED-209 should have only the most vestigial face, so it looked blank and staring and dumb. Craig's solution to this anthropomorphic problem was to design air intakes in a certain configuration that looked like a mouth. They came together in a very simple truncated triangle that made a rudimentary facial expression."

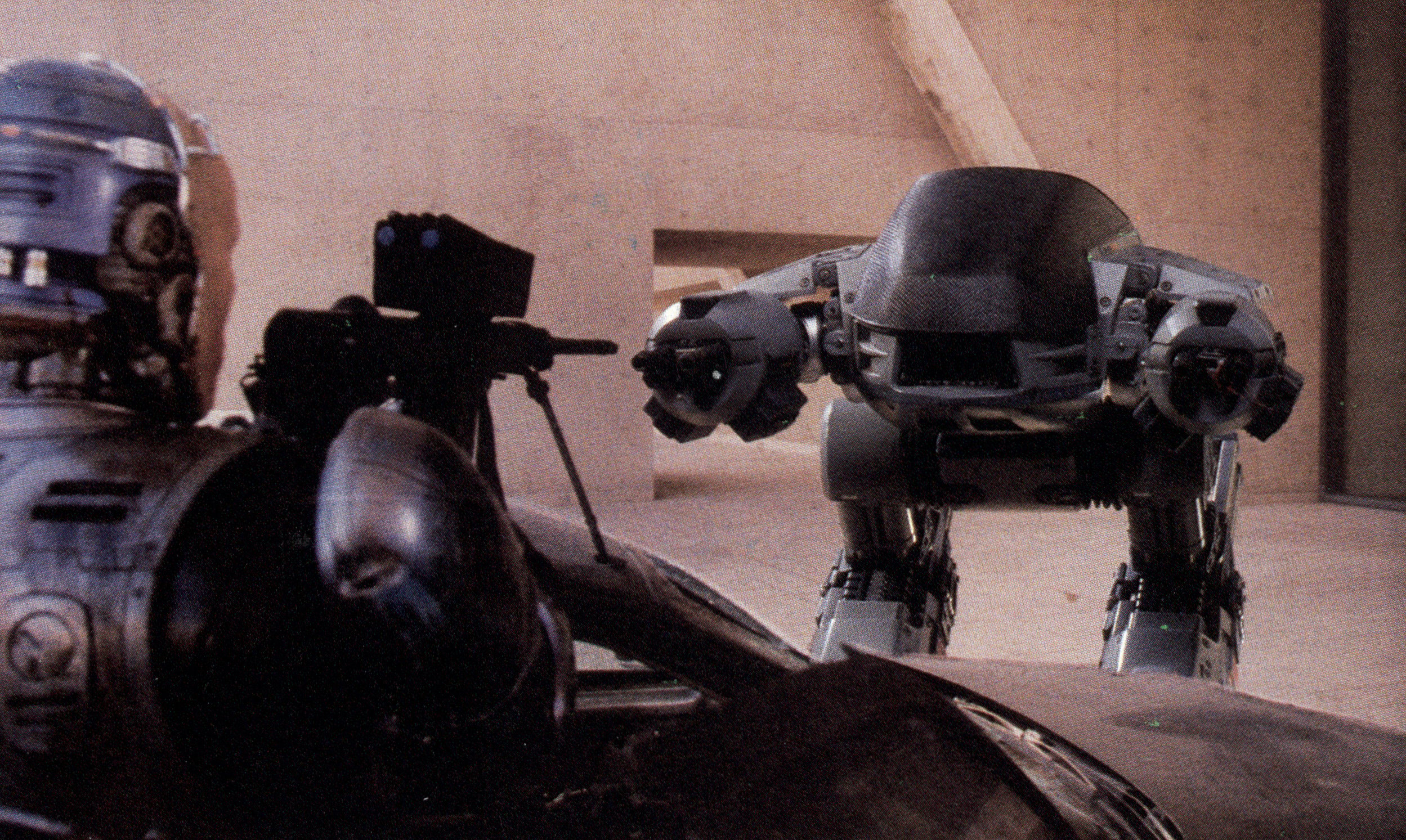

The final showdown between ED-209 and RoboCop, beginning with ED's ridiculous attempt to navigate a steep set of stairs as he pursues his biomechanical adversary, is a classic comic confrontation that is one of the highlights of 1987's special effects. As animated by Harry Walton, Randy Dutra, and Tippett, this final sequence is a bravura bit of characterization and performance that clearly establishes ED-209's great strength and inept weakness, while still carrying the film's story resolutely forward.

Of all the stop-motion effects Tippett supervised for RoboCop, ED-209's disastrous tumble downstairs was the biggest worry — even before producer Davidson called Tippett and begged him for a laugh or two to lighten the grim tone of the film. “As the picture was coming together," Tippett relates, “the producers felt that it had too maniacal a mindset — it was getting very intense as people would swear at each other and blast their guns for 15 minutes at a time, and there was no relief from it. We had always wanted to do something funny with ED in the stairwell battle, but before we could do that, we had to arrange his fall down the stairs, and I really had no idea how we were going to do it."

We shot background plates on the full-sized stairwell set and I tried to figure out all these screwball ways to fly ED down to simulate his fall. We were really getting down to the wire, we had to get the shot, so we took all the information available and built a great duplicate miniature set of the stairwell. Harry Walton placed the set at a 45-degree angle and tied the ED-209 model down with a small pin in his foot that could be removed to let him fall down the stairs. Harry loosened all of ED's joints and loaded him with lead so he had weight. Then he pulled the pin and let him fall downstairs. We shot it at about 75 frames per second. The only real trick was animating him into the fall and then getting him out of it at the end."

At the base of the stairs, the frustrated ED-209 robot has a mechanical fit, which provides the first of several laughs the producers and filmmaker felt were necessary to help the audience through the film's last few moments. "Originally, we had done a couple of shots where ED was lying at the base of the stairs kicking and he seemed to have a great deal of weight," Tippett says. “Then Paul said, 'Why make the movement project so much weight? Why not make him more like a mad bee or a baby?' At that point, we pulled out all the stops. Harry Walton animated the shot where ED flails in frustration, and he made him go pretty crazy. He went against all the rules we would normally follow to cap that sequence off with a touch of humor."

“I suddenly got this sense of amazement and enthusiasm, and I realized that this was why I got into this business — to do that kind of stuff.”

After RoboCop fires a deadly barrage at EDs head, one assumes that's the end of their battle. To add another bit of fun to the proceedings, Tippett arranged a low-angle shot as ED-209 walks into frame, apparently still stalking RoboCop, only to have it stagger and fall into the shot, revealing that its head is completely gone. "I was initially going to handle that very matter of factly," Tippett admits, "but then one of the producers called and said the film had gotten too serious and we needed another laugh at this point. 'Make him look like he's drunk,' he said, so I took that idea and tried to make it look like he was out of control."

What has pleased Tippett so much was working on a film made by talented and dedicated professionals trying to do the best job possible.

"Watching our editor, Frank Urioste, assembling our animated footage, I got a feeling I haven't had in so many years," Tippett says. "I was seeing scenes I had worked on, and I suddenly got this sense of amazement and enthusiasm, and I realized that this was why I got into this business — to do that kind of stuff."

Tippett, who made a name for himself while working at ILM on the original Star Wars trilogy, as well as consulting on Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom, would follow up his work on RoboCop with several impressive projects. They included the George Lucas-penned fantasy Willow; he was the "dinosaur supervisor" on Jurassic Park; and later re-teamed with Verhoeven on Starship Troopers.

You'll find our podcast interview with RoboCop cinematographer Jost Vacano, ASC — who also shot Starship Troopers — here.