Revenge Served Cold: Sleepers

Cinematographer Michael Ballhaus, ASC, BVK helps director Barry Levinson realize a harrowing tale about four youths’ collective experience with violence and retribution.

Sleepers, an autobiographical novel by Lorenzo Carcaterra, created a firestorm of controversy when it was published last year. And now, a cinematic version of the story — so powerful that it may tempt some viewers to avert their eyes — has emerged to fan the flames even higher. Directed by Barry Levinson for Warner Bros., it was primarily photographed on the streets of New York City by Michael Ballhaus, ASC, BVK.

Sleepers is told in three acts spanning two decades. Act One tells of four altar boys from the tenements of Manhattan's Hell's Kitchen, who are sent to an upstate reform school after a prank escalates into a near-fatal accident. The "home for boys" inmates are referred to as "sleepers." In Act Two, their lives are warped by the mental, physical and sexual abuse they suffer at the hands of four perverted guards. The boys triumph momentarily when the inmates win a football game against the guards, but during the night their leading player is beaten to death and the youths are battered and placed in solitary confinement. In Act Three, the four have grown to manhood. Two are mobsters, another is an assistant district attorney and the fourth (representing the tale's author) is a newspaperman. When the two gangsters encounter one of the ex-guards in a saloon-style restaurant, they kill him. The assistant D. A. and the journalist, with the aid of the Mafia and a priest who once did time at "the home," manage to save their friends and bring death or ruin to the other ex-guards.

Carcaterra and his publishers at Ballantine Books insist that the story is true, but refuse to name names. The New York Times and the Washington Post question its authenticity, while the NYC District Attorney's office and the Juvenile Authority deny everything. Nobody has been able to prove or disprove the novel's veracity. ''The author was on the set a lot and he always had the right answers," Ballhaus says. "He was very helpful with little details. I believed him, and Barry did, too."

A pleasant, soft-spoken artist who perfected his craft in his native Germany while shooting 15 pictures for director Rainer Werner Fassbinder, Ballhaus has long been one of America's busiest and best cinematographers. Since arriving in the States, he has lent his eye to such diverse films as Heartbreakers, After Hours, The Color of Money, Broadcast News, The Last Temptation of Christ, The Fabulous Baker Boys, GoodFellas, What About Bob?, Bram Stoker's Dracula, The Age of Innocence and Quiz Show.

“Sleepers was a picture full of challenges, but it was a dream to do. It went fairly smoothly, and we came in ahead of schedule and under budget.”

— Michael Ballhaus, ASC, BVK

"This was my first time working with Barry, so I called Allen Daviau [ASC], because he had worked with him on some great pictures [Avalon and Bugsy]. I got some advice from Allen that helped me. I must say, I was really surprised at how visual Barry is as a director, and he gave me freedom to experiment. I'm always prepared with a basic idea or concept of how a scene could work, and most of the time when I'd propose things to Barry, he'd say, 'Yeah, that's good; let's try this and go a little further.'

"I enjoyed shooting a movie where we didn't have to make compromises because many times in our profession we have to deal with major movie stars and we can't do the lighting we want because we have to make somebody look more beautiful or younger," Ballhaus notes. "In this picture, we had many stars, but they all fit into it so well that we didn't have to compromise."

An unusual aspect of the film is that several very notable actors appear in roles subordinate to those of the four younger thespians, and their performances transcended the profit motive. Says Ballhaus, "Dustin Hoffman appeared as a favor. Barry called him up and asked, 'Would you come in for two weeks?' It was such a great help for the project, because a story in which the lead actors are four boys whom nobody knows is a hard sell today — especially if it's not an action movie or a love story. But stars like Dustin, Robert De Niro, Brad Pitt, Kevin Bacon and Jason Patric helped to get the picture off the ground."

Ballhaus recalls that he and Levinson discussed photographic style at length. "We wanted a different style for each act," the cinematographer explains. "The first takes place in Hell's Kitchen, and we decided it should have a warm look because the kids are growing up there and they're safe. Even if there's trouble at home — one boy's father beats his mother — they have wonderful friendships, and for them, it's a great time. It's secure and warm and they're protected. It's all controlled by the Mafia, but it's controlled. We used long lenses to make [the neighborhood] kind of pretty and exciting.

"For the second act, in the reform school, we went in the other direction," Ballhaus continues. "From the outside, the place looks perfectly wonderful, like a university campus, but we find out that for these boys inside, it's a living hell. We wanted a cool, dark look — not friendly or warm. There's not one yellow or warm scene inside the school. It's all bluish and contrasty, and we used a lot of short lenses.

"We wanted the third act, which takes place 15 years later, to look more like real life, with neither the warmth of the first act nor the coldness of the second. The guys are grown up and now we see them in the real world."

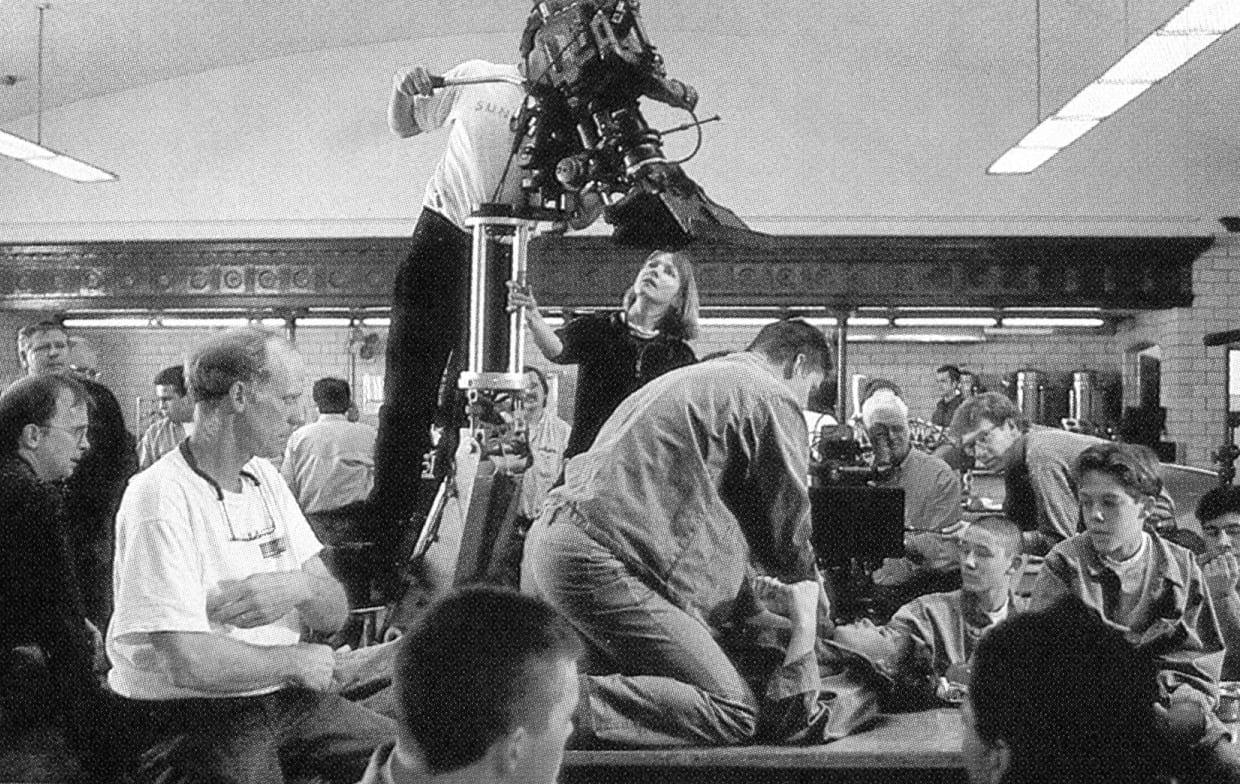

The camera crew in New York consisted of crack professionals with whom Ballhaus has worked many times before. Jerry DeBlau was the gaffer, and Dennis Gamiello served as key grip. Ballhaus' son, Florian, who is a director of photography in Germany, was the operator.

The movie was filmed in Super 35. In this format, the original negative is photographed with spherical lenses at the full-frame aperture, for an image that is 0.980” wide and 0.735” tall — a full four perforations. (The standard aperture is 0.864” x 0.630".) At the laboratory, the image is later anamorphosed (squeezed) so that prints can be projected through an anamorphic lens for widescreen presentation.

"The film will be released in 2:35:1," Ballhaus explains. "A lot of people ask me about the difference between shooting with anamorphic lenses and shooting in framing anymore. It's always panning and scanning. I do widescreen in Super 35 because more people see a movie on tape than they do in the theaters, so I feel obligated to make it look good on tape. "If you shoot in Super 35, you have the option to open up the bottom; I shoot with a common top line so that we have a lot [of room] on the bottom. I keep that area clean, so that when we go to video we have something to go to. You can keep the top and the sides, which worked great for Age of Innocence. It wasn't compromised; it was almost the same composition, only we saw more on the bottom. Shooting in Super 35 also allows me to use my regular lenses, and a much wider range of them.

"You also have to use a lot more light in 'scope — at least an f5.6 to make a really crisp, sharp image and get some depth of field. I can shoot with an f2 [in Super 35] because the lenses are much faster, so I need less light and less time to light. I can even shoot the streets of New York City at night with available light. You can't do that in 'scope because the lenses are not fast enough. When [Stephen Burum, ASC] did Mission Impossible, he shot a lot of night stuff on 5298 [Eastman's 500 ASA film] be¬ cause he needed an f5.6. In Super 35, I can shoot the same thing at f2.8 with [200 ASA] 5293. This compensates for the next-generation optical squeeze that's necessary when you shoot Super 35."

As a result of this choice, Ballhaus shot most of Sleepers on Eastman 5293, using 5245 for day exteriors. "When shooting Super 351 try not to shoot much 5298," he says. "I did a lot of the night shots with 5293 just to have less grain, so we had to light many scenes instead of using available light."

There were exceptions to this strategy, however. Assessing one Act Three night sequence shot on location in New York City, Ballhaus recalls, "Two of the grown boys walk into a bar, and we shot with 98 in available light because we had Broadway behind them — and we couldn't light that. [For another scene], shot under the elevated subway tracks, we shot 98 and we needed a lot of big lights on the roofs. We used a 12K HMI for moonlight, softened with a big 6' by 6' silk in front, but it was basically all lit. We owned the street, which was great because we could do whatever we wanted there. It was a lot of work to light all that, but it worked quite well."

He continues, "We had very interesting locations and permission to completely change one street to make it look like it would have in the late Sixties. They put a lot of money into that location and did a wonderful job on the neighborhood — dressing the shops, putting fire escapes on the walls, and so on. Our production designer, Kristi Zea, did a marvelous job. Most of the people there liked the activity going on in their neighborhood, and they got little jobs and made some money. There was great atmosphere on that street."

The film's opening scene is an eye-grabber. The camera looks straight down at the four boys sunbathing on a roof, then descends four stories to show the hectic pace of life on the shadowy streets of Hell's Kitchen.

"That shot was made with the Akela crane," Ballhaus explains. "The crane was originally made in Russia, and then the company modified it here; they now have three or four of them. It extends to 75 feet. From the fourth floor of the building, where the kids were, we swooped around over the edge and down into the street and around into another street. I kept the same aperture throughout the shot. We tried to fill the shadows a little with a couple of big reflectors; they were about two stops under, but I didn't want to open up, because it gets so bright and I wanted the quality of the dark street."

Capturing the Big Apple's authenticity was vital. "We wanted the feeling that it is Hell's Kitchen; as a result, scenes in which you could see the skyline were shot in Manhattan," says the cinematographer. "People who know New York will be able to tell that we really shot it there. The rooftop where the boys played was really in the middle of Hell's Kitchen. The other streets were actually shot in Queens because we couldn't close off the streets in Manhattan, but the look was the same."

In many of the Hell's Kitchen scenes, well-known Manhattan landmarks — the Empire State and Chrysler buildings, for example — can be seen in the distance, adding to the authentic feel. But Ballhaus felt that many of the best locations were in the Queens neighborhood: "We shot a scene there in which two thugs try to rob a boy carrying racket money in a dark passageway between houses. It was really dark in there, and to get some light — not too much — I had some 12Ks along the sides. You could see the walls with a nice backlight; to keep the dark alley feeling, I used very little fill."

Weather, the natural enemy of location filming, turned a benign face on the Sleepers company, and the filmmakers made the most of the one vicissitude they encountered. "We were very lucky," Ballhaus admits. "We started in New York in summer, and when we finished we were at the reform-school location in Connecticut. We needed to create the feeling of autumn and a bit of winter there, and sure enough, one day it started snowing. [The snow] was not in the script, but we just said, 'Okay, it's snowing and we need that.' We invented something quickly, and then raced out [to make use of] the snow."

Confronted with good weather on the rest of the shoot, the company made their own rain for several NYC street scenes. Ballhaus notes, "The one in which the two friends are walking under the L tracks was done in Brooklyn with big rain towers. The rushing trains became a motif for the city, and the noise worked quite well along with the time of day when they meet."

For daylight scenes, Ballhaus used a lot of fill due to the extreme brightness of the sun. To soften things, he utilized a Tiffen Soft-Con filter and a 12' x 12' frame of bleached muslin — which he would either use for bounce (with the sun aiming into it for backlit shots) or diffusion (often with two 12Ks shooting through it). For some scenes, such as a key sequence in which the boys torment a hot dog vendor, Ballhaus had a huge silk hung from above to soften the light.

"We also used filters, especially in the first act, to get the softness of the colors [of the period], so it wouldn't have the look of modern New York," says Ballhaus. "In addition to my SoftCon filters, I used a Tiffen black net to make everything a little softer and friendlier. Whenever it was too bright, I used ND6s and ND9s to bring the f-stop down. In daylight, I always tried to keep the exposure around f4 or 5.6."

In one eerie sequence, a Mafia leader informs a black gang boss named Little Caesar (Wendell Pierce) that the latter's younger brother, the football player who had supposedly died of natural causes in the reform school, had actually been beaten to death by a guard who was now a dope pusher in the neighborhood. The gangster and his cronies later take the killer for an evening ride and execute him next to an airport runway.

"I wanted Little Caesar's headquarters to be a very special location," Ballhaus recalls, "and I explained to [production designer] Kristi Zea that we shouldn't shoot it in some ordinary room. We looked at a lot of locations and none were quite right, until we finally found an old movie palace in Brooklyn. We walked in there and I said, 'This is the place!' It wasn't realistic, but sometimes a movie has its own reality. I like moments when you heighten that sense with a place that just looks great. He could live in an old movie theater, so why not?

"Little Caesar shoots the guard at the airport just as an airplane comes into the shot," Ballhaus adds. "A lot of people might think that [the plane] was a CGI effect, but it was a real plane that came down and we shot it in the last moment of daylight. We knew that if we got lucky, there would be a plane; if not, we could al¬ ways add it in later with CGI. The shot was well-prepared; we lit it, waited until the light was right, and shot several takes. Then all of a sudden, Barry said, 'Oh my gosh, here comes a big plane — let's go!' It was per¬ fect timing and quite dramatic, shooting this guy as the plane was coming down. We added the landing lights on the ac¬ tors so that they could be seen shortly before the plane came in. We had a little backlight, but we filmed it basically with very little light. The whole scene took about an hour to shoot."

The reform-school location was actually a facility for the mentally disabled near Newtown, Connecticut. "It's a big compound, but most of the buildings are empty, with only one or two buildings still busy," Ballhaus reveals. "The location was perfect for us: it had the right architecture and we had the freedom to move in and out of the buildings. The only set we actually built was the cell where the guards imprison one boy. We couldn't find a space like that anywhere. All of the other places, such as the basement where the guards take the inmates and the long hallway leading to it, were real."

In one nightmarish but bravura moment, the camera hurtles down the long, blindingly bright basement corridor that leads to the torture room. "That was a complicated shot," Ballhaus relates. "We did it with a Steadicam on a dolly and we changed speed from 24 fps to three fps, which created the 'racing' effect. But when you shoot at three frames, the camera has to be really steady — otherwise, it jiggles around like crazy because of the exposure time. Larry McConkey was our Steadicam operator; I always use him when I'm shooting in New York. We lit the corridor with a strong source so it would go white at the end."

Ballhaus is proud of his son's expertise in the handheld scenes, noting, "Florian always got the right feel for when to move the camera, especially in all of the flashbacks in the room where the guards torment the boys. When you're doing handheld stuff, it's all about intuition and having a feel for the scene."

Arriflex cameras were used throughout the production. "We shot a lot of the handheld stuff with the new 435," reports Ballhaus. "It's a brand-new camera, and it's beautifully designed. It's light and incredibly steady, and it goes up to 150 fps.

"Arri's Variable Primes, made by Zeiss, are also interesting tools," Ballhaus reports. "The three lenses cover the whole range from 16 to 105mm, and are very sharp. They start from 16 to 35mm, then go from 32 to 65mm, and 65 to 105mm. These zooms are very fast; they open up to f.2, and they're almost better than the primes. It's not too often that you use the whole range of a zoom, but sometimes you just want a little motion in [the shot], and these lenses are perfect for that. With regular zooms you always need at least an f4, but with these lenses you can shoot at f2. We worked in many low-light situations, such as on a subway, which we couldn't light."

Subtle over-cranking was used in several scenes. Ballhaus especially liked the sequence at the beginning of Act Three in which two of the grown "sleepers" accidentally encounter one of their former reform school antagonists in a restaurant. In a moment of fate, one of the men goes back to the restroom and sees the ex-guard eating alone in a booth. "We did a speed change from 24 to 50 fps to make this moment of recognition a little bigger," Ballhaus says.

The 435 ES's electronic mirror shutter can be continuously adjusted from 11.2° to 180° while the camera is running to compensate for such speed changes.

The cameraman continues, "Later, at the moment when [the adult "sleeper"] turns, we shot at 30 fps. We shot at 30 fps again when he's in the men's room and looks up into the mirror, to heighten the moment when he realizes that he's found the man who destroyed his life. You can see in his eyes that he has to kill him."

Referring to another slow-motion scene, Ballhaus say, "In the school, when the guards beat one boy and throw him into a dark cell, we shot at 120 fps. The whole sequence is intercut with shots of the football game that had just been won by the boys. This was a stylistically interesting way of telling the story. Barry was struggling with how to present the football game. Finally, he said, 'I think it's best to do it as a flashback from the point of view of the boy in the cell, with him remembering what happened.' That gave us the freedom to do wild things, which I enjoyed. We shot it handheld in black-and-white, which added a lot of drive to the story."

All of the black-and-white flashbacks were actually shot on monochromatic stock, though Ballhaus points out one exception: "It's a scene during the trial, when one of the guards, Ferguson, is on the stand. We see a flashback in which he comes into one of the boys' rooms and tells him, 'I just f d your friend.' Then the boy he has just raped comes in and puts a knife to his throat. That scene was originally shot in color as a regular scene. But Barry decided in the editing that he wanted to make the moment of Ferguson's breakdown in the courtroom more dramatic by intercutting the scene as a flashback. So we projected the color footage, and Florian shot it in black-and-white off the screen, making handheld moves on the image. That is what was cut into the courtroom scene."

Overall, Ballhaus "tried to give the courtroom itself a rich and dark look, with a bluish light in the background and a warmer light on the actors. I used a lot of smoke, in general, to give it a bit of atmosphere and bring out the beams of light coming in."

Obviously pleased with the outcome of his collaboration with Levinson, Ballhaus recalls with a grin, "Sleepers was a picture full of challenges, but it was a dream to do. It went fairly smoothly, and we came in ahead of schedule and under budget."

Florian Ballhaus later became a member of the ASC, his feature credits including Flightplan, The Devil Wear Prada, RED, The Book Thief, Snatched and I Feel Pretty.

If you enjoy archival and retrospective articles on classic and influential films, you'll find more AC historical coverage here.

Access the every issue of AC and every story from more than the last 100 years with our Digital Edition + Archive subscription.