Rock ‘n’ Roll Filmmaking: A Hard Day’s Night

A rushed script. Faulty camera gear. Benzedrine. Gilbert Taylor, BSC on shooting with The Beatles.

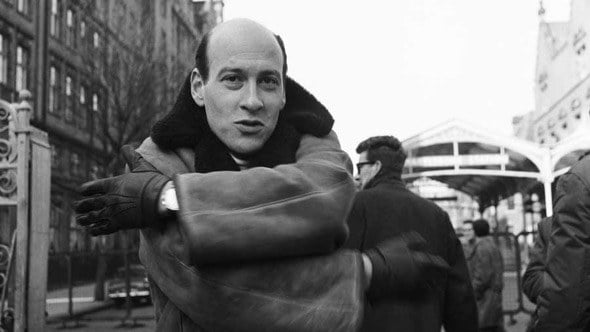

In late 1961, 47-year-old British cinematographer Gilbert Taylor, BSC teamed with 29-year-old American director Richard Lester on his first feature, It’s Trad, Dad! (1962), a humorous — if slightly surreal — youth film about the interest in traditional, or “Dixieland,” jazz that was sweeping England at the time. Patterned after 1950s American rock ‘n’ roll movies, Trad features misunderstood teens, stuffy adults and plenty of musical performance sequences. “Dick’s enthusiasm for music and filmmaking blended together in mad unison appealed to my mental and physical state at the time,” Taylor told American Cinematographer in 2006, noting that Trad became a sort of template for one of his most popular and often-imitated films, A Hard Day’s Night: “In 1964, when the Beatles came of age, I was given a poor script by Dick and told we basically had to make it up as we went along. The only thing set was the music, the rest we had to invent daily!

Ready or not, production began on March 2 of that year, with the film released in the U.K. just months later, on July 6, and the U.S. on August 11.

The modestly budgeted and poorly planned film designed to quickly cash in on Beatlemania is now a classic in its own right.

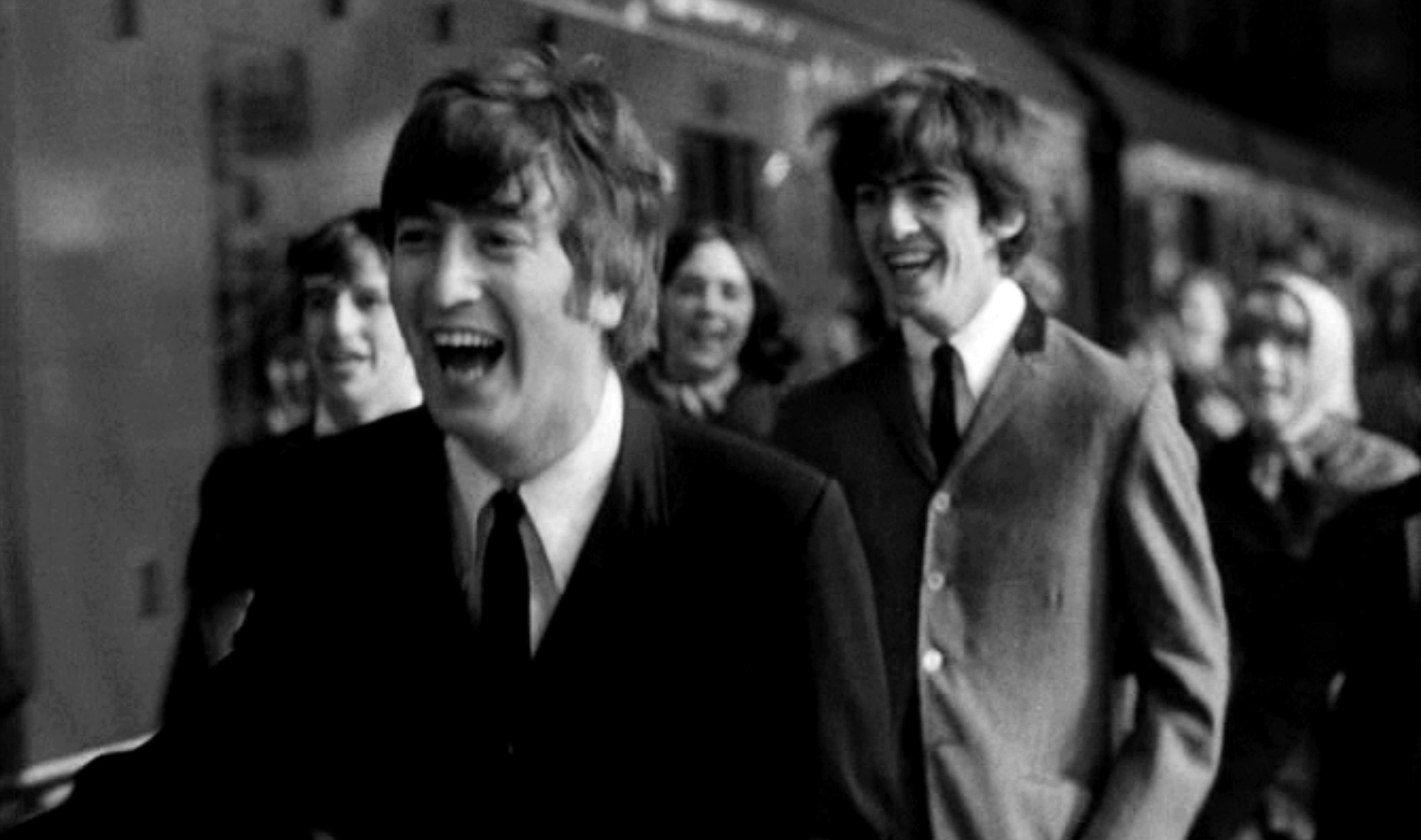

Hastily written by Alun Owen after he spent time on the road with the band to understand their distinct personalities, the script’s narrative shortcoming partially explains the finished film’s disjointed structure, but it was Lester and Taylor’s decision to shoot in a documentary-style fashion on live locations that helps keep Hard Day’s Night energetic and fresh. The Fab Four were hardly acting and the real world surrounding them gives this pop “day in the life” snapshot of the band an air of authenticity that was a rarity in its day.

Visually, this mood is set with the opening credits sequence, as Paul, Ringo, John and George are chased through the Marylebone train station by a frantic pack of female fans afflicted with Beatlemania. The action was captured with multiple cameras, each fitted with a 10:1 zoom, which allowed Taylor’s crack operating team to cover the scene much like a sporting event. “There was very little lighting of any sort as the authorities would not allow us to control the station in any way — no stands, not even a tripod, usually,” he remembered. “We also had a very limited budget and couldn’t afford generators, so any fill was just coming from a little handheld, battery-powered lamp. They wouldn’t have let us bring generators or cables onto the platform, anyways. Things were not the same in England as they were in the U.S. — public spaces were not easily used for filming.”

“The boys had terribly rough edges and weren’t really adept and memorizing lines. So the real locations kept life in each shot.”

— Gilbert Taylor, BSC

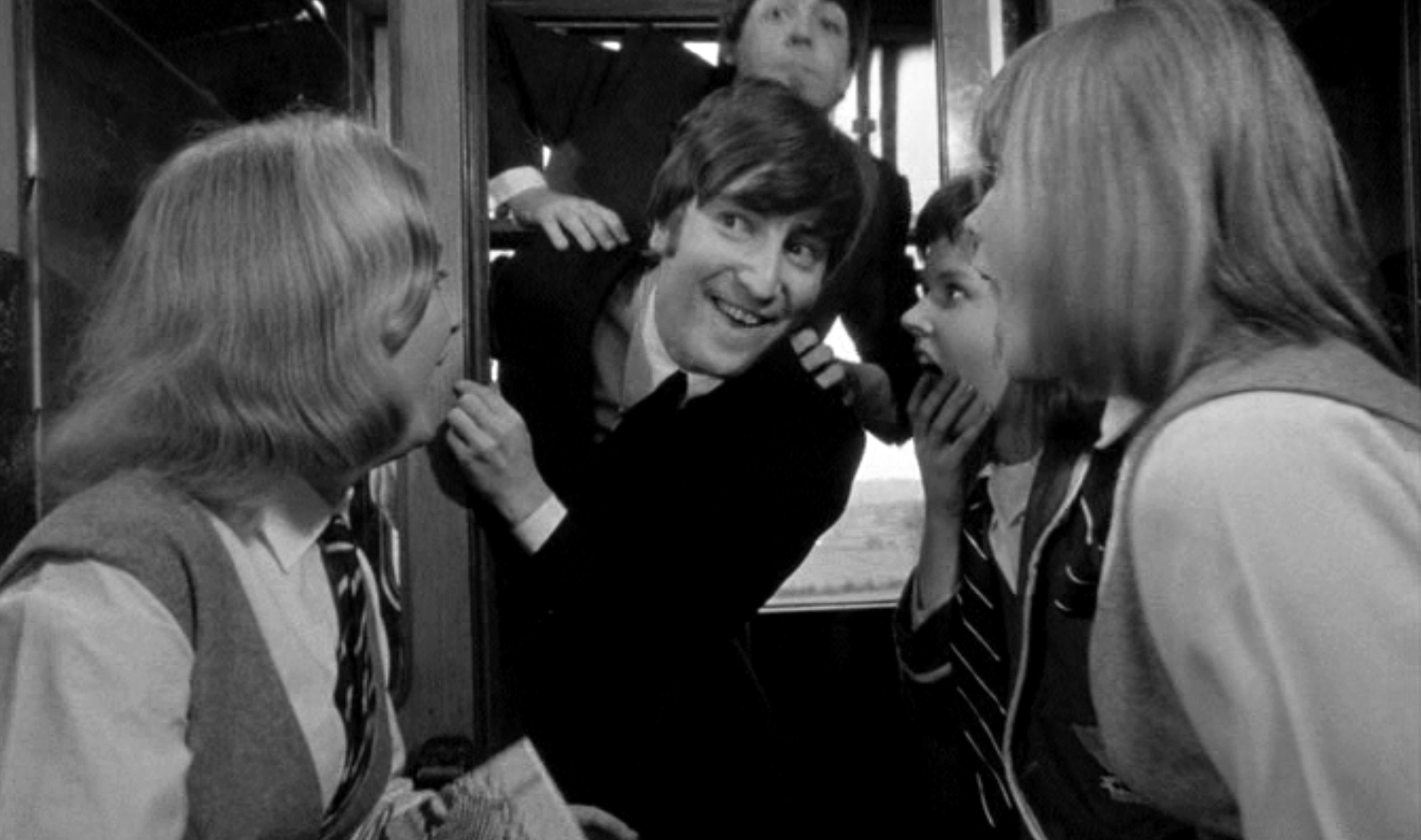

But Taylor would continually turn adversity into advantage on the film: “We then took a real train journey with little or no extra lighting, just a little 4K generator to power some lamps in the ceiling, tracking down the corridors on roller skates and such. We were always 'documentary.' But the raw quality of the shoot was there on the screen, and Dick was amazed at our rushes.”

Taylor noted that “we had to book seats on the train because that’s the only way we could get aboard to film,” agreeing that shooting the train sequence “Hollywood-style” on stage with rear projection would have sucked the life out of it. “The boys had terribly rough edges and weren’t really adept and memorizing lines. So the real locations kept life in each shot.”

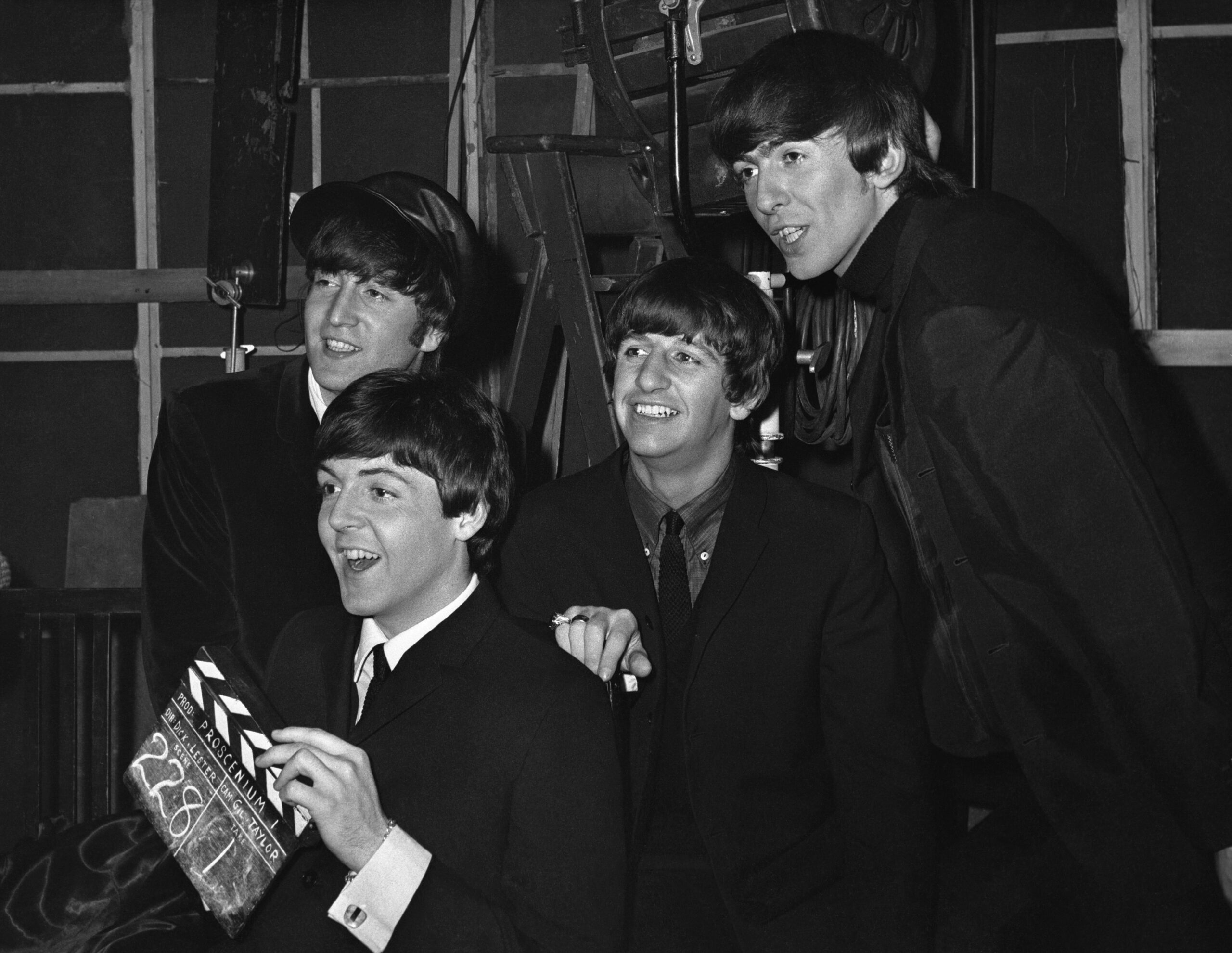

The film’s TV studio-set performance sequences filmed at Twickenham Studios gave Taylor a chance to capitalize on his penchant for high-contrast black-and-white — in part to make up for the shabby stages he was forced to use. “The white backings there were terrible,” he recalled. “They were just filthy, so the only solution was to just fill them with light to kill the dirt and then overexpose the hot areas by several stops. It they were an f16, I’d shoot the boys at a 5.6. We were also shooting directly into 10K lamps behind them, using the intense light to explode the image and make things as exciting as they could be.” And the Beatles, clad in natty black suits and set against this searing backdrop, literally pop off screen.

For Taylor, Hard Day’s Night was not only a chance to break with convention, but to also embrace a particular ‘happy accident’ that would soon become a rock film convention: “While filming the boys on a cricket field [at Thornbury Playing Fields], a helicopter arrived and Dick Lester asked me to go up and get some aerial shots,” the cameraman said. “So I did, but the camera had a faulty battery. Instead of scrapping the opportunity, however, I instead changed the stop and lowered frame rate to compensate and shot the boys in action. When I got back on the ground, I didn’t say anything to Dick about it. But when he saw the rushes, he went raving mad! He loved the sped-up footage, so we went back to the field a few days later to shoot more on the ground, and that became the sequence. That’s the way the whole picture was made — off the cuff.”

As for the trials of making the picture and keeping pace with “the boys,” Taylor confesses that Benzedrine helped him get through the arduous shoot: “I’ll admit to that.”

While many cinematographers at the time favored primes over zoom lenses — always seeking better image quality — the utility of zooms assured that they would always have a place in Taylor’s kit. “I love 10:1 zooms because I can find just the right angle I want,” he said, “and even change that angle, especially while doing tracking shots. I never used a fixed lens for that, because I wanted the flexibility to alter my angle to follow the performance or the composition. Of course, that meant having another assistant, but it worked for me!

“And while American cinematographers used Bausch & Lomb Baltar lenses at the time, I always favored Cookes. They have a very particular, soft look that I just find it so much more pleasing. One could use filtration on the Baltars, which I always found so hard-edged, but it was never the same.”

In 2014, a major 4K restoration of the film was made by Janus Films, The Criterion Collection and Apple Corps for a 50th anniversary Blue-ray release. This followed a photochemical restoration that had been done 20 years prior. Criterion located most of the film’s original camera negative, stored at Pro-Tek Vaults and in generally good condition, with the exception of reels 1 and 10 — which were missing. A fine-grain positive of the picture was soon found archived in England, and the missing reels scanned at 4K at Deluxe Digital London.

The remainder of the film was scanned in 4K at Sony Colorworks in Culver City, making A Hard Day’s Night Criterion’s first complete 4K restoration project.

Before restoration work began, the project was color-graded by Sheri Eisenberg at Sony ColorWorks. While the image quality of reels 1 and 10 was acceptable, they also had increased contrast due to their inclusion of title sequences created via traditional optical printing.

Picture restoration was performed by 10 artists over a month’s time at Criterion’s offices in New York, using a small but powerful arsenal of tools, including Digital Vision’s Phoenix, used as a first automated pass, for dust and dirt repairs. MTI Film Correct was then used, with artists identifying additional trouble spots. Pixel Farm’s PFClean was then used for fine tuning.

The film’s extensive use of handheld cameras created issues as the resulting motion blur is typically misinterpreted by automated programs. Due to this, the largely improvisational “Can’t Buy Me Love” sequence described by Taylor was problematic and required extensive manual cleanup, especially due to the aerial footage — which was also handheld.

Director Richard Lester himself cleared up questions about the film’s aspect ratio. Shot in 1.66:1 — common for the time — the picture was frequently exhibited that way. But a title card found on a single frame from the remaining original print leader attached to one reel read “1.75/1.” The filmmaker confirmed that the latter was indeed correct, and the completed restoration was released as such, perhaps for the first time since its original release in 1964.

Of note, screenwriter Alun Owen earned an Academy Award nomination for Best Writing, Story and Screenplay — Written Directly for the Screen.

Taylor’s other feature released in 1964 to great acclaim? Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb. His other credits include The Bedford Incident, Repulsion, Frenzy, The Tragedy of Macbeth, The Omen, Star Wars: A New Hope and Flash Gordon. He was honored with the ASC’s International Award in 2006.

If you enjoy archival and retrospective articles on classic and influential films, you'll find more AC historical coverage here.