Wrap Shot: Dr. Strangelove: Or How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb

Gilbert Taylor, BSC discusses his work on Stanley Kubrick’s dark Cold War satire.

For veteran cinematographer Gilbert Taylor, BSC — then just 51 — 1964 was a banner year, seeing the release of not only director Richard Lester’s musical fantasy A Hard Day’s Night, starring The Beatles, but Stanley Kubrick’s Dr. Strangelove: Or How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb, which became an instant classic.

Featuring graphic, high-contrast illumination from Taylor, “Strangelove was at the time a unique experience as the lighting was to be incorporated in the sets and with little or no other light used,” the cinematographer told American Cinematographer in 2006, upon being honored with the ASC International Award.

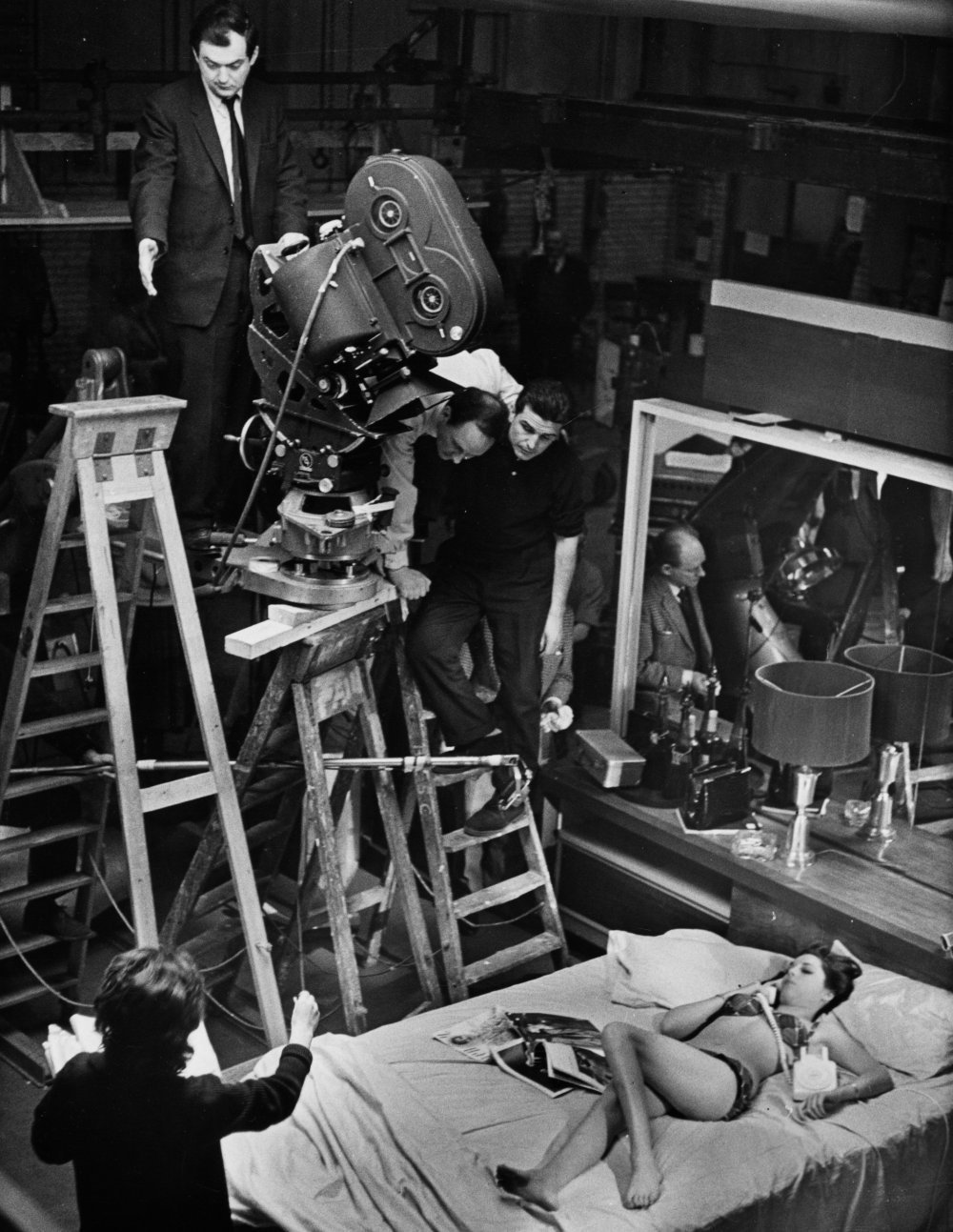

This use of source lighting is perhaps best exemplified by the extensive scenes set within the “War Room,” the ominous and iconic command and control center designed by art director Ken Adam, where American President Merkin Muffley (Peter Sellers) and his advisors mismanage a nuclear crisis launched by a rogue Air Force general.

Featuring a gleaming black Formica floor and a 22"-across circular table lit by a halo-like ring of white-hot overhead fluorescent fixtures, the immense set was designed to suggest an epic poker game — at which the players gamble on the radioactive fate of mankind with the action displayed on huge electronic display boards looming over all. “Lighting the war room was sheer magic, and I don’t quite know how I got away with it all!” Taylor said. “But much of it was the same formula based on the overheads as fill and blasting in the key on faces from the side.”

“Kubrick only got so far in regarding any sort of stop or lens. His idea was to shoot a Polaroid of the subject, show it to me and ask, ‘What do you think?’ I’d say, ‘It’s dreadful,’ and that’s how we got on.”

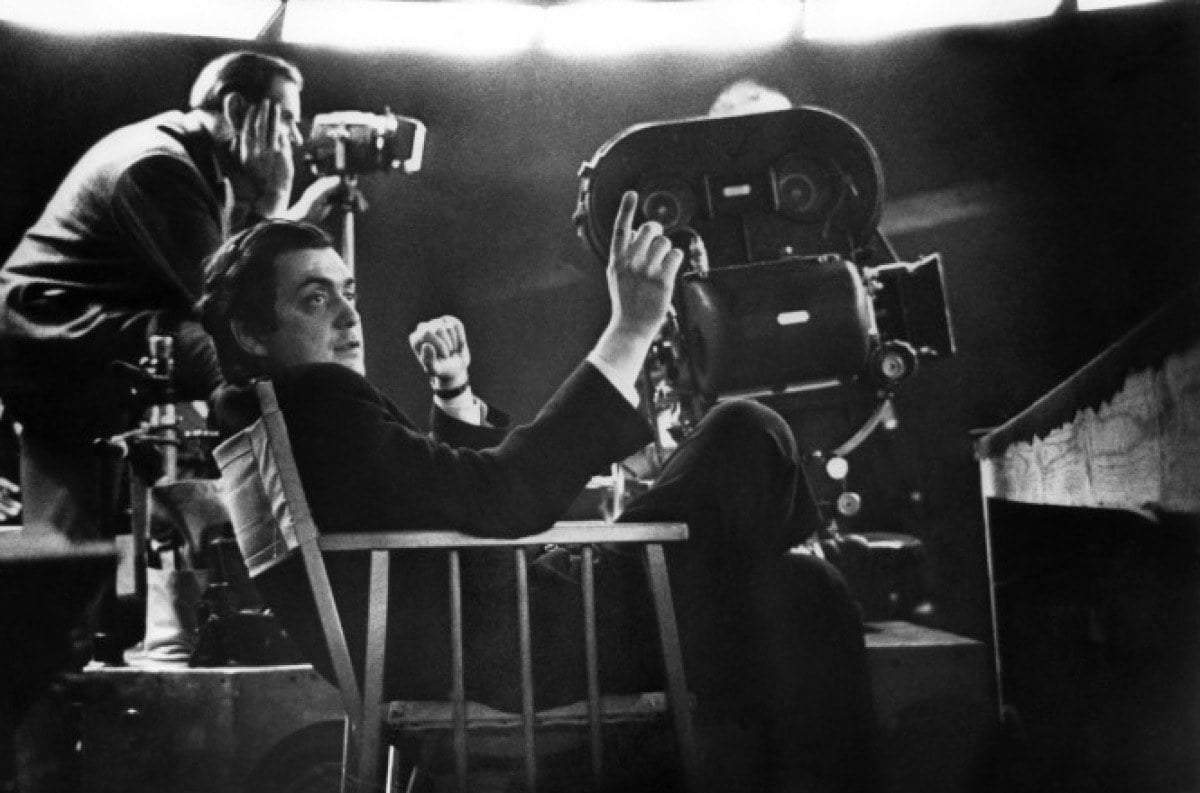

While his director was an experienced still photographer and wanted to be intimately involved in all aspects of the production, Taylor attested that “Kubrick only got so far in regarding any sort of stop or lens. His idea was to shoot a Polaroid of the subject, show it to me and ask, ‘What do you think?’ I’d say, ‘It’s dreadful,’ and that’s how we got on.”

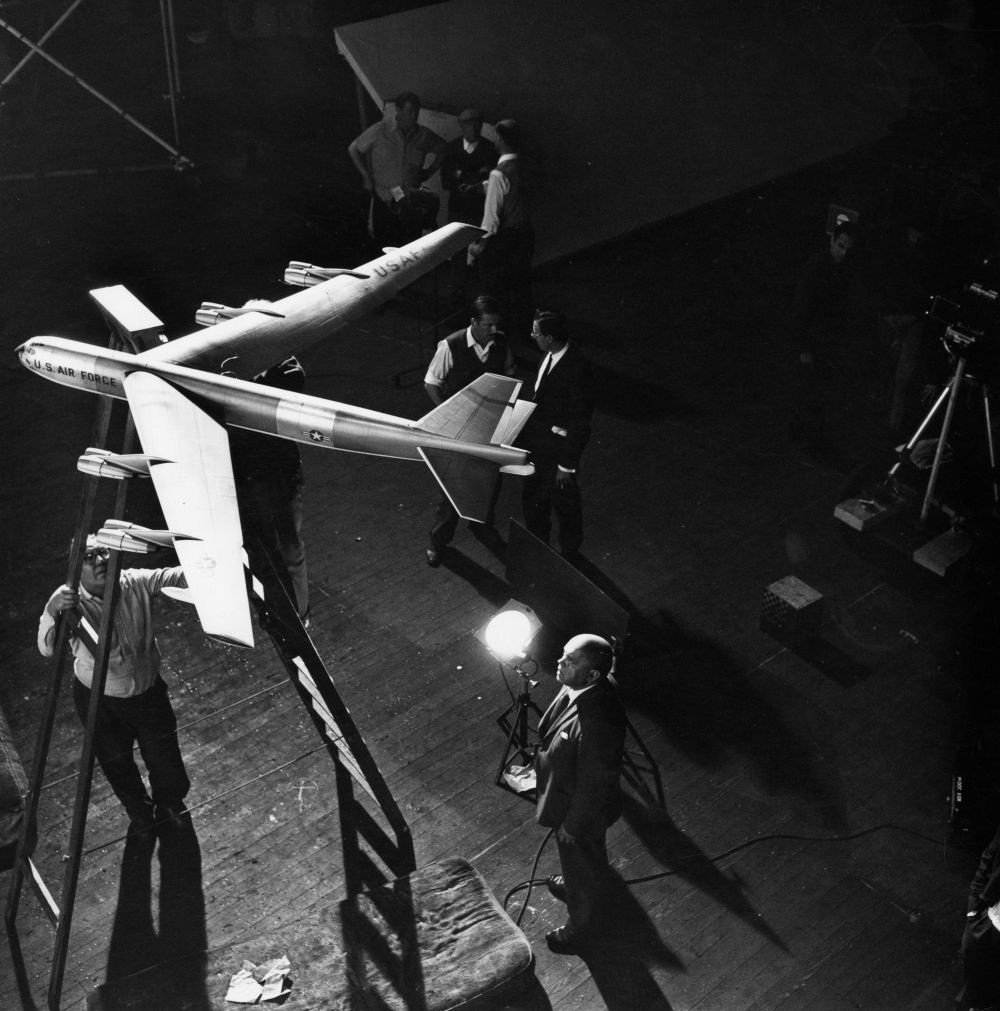

During the film’s preproduction period, Taylor shot the extensive aerial photography needed for rear-projection plates used in sequences set aboard a wayward B-52 — drawing on the cameraman’s extensive experience of doing such work while in the RAF. “Stanley hated being airborne,” Taylor told AC, “so during prep on Strangelove, I did about 28,000 miles in a B-17 Flying Fortress, shooting aerial material. I remember the night we took off; it was pitch black at four o’clock in the afternoon, and we were going up with the Fortress to Iceland and then Greenland. It was semi-snowing at the airport, and suddenly someone said, ‘Stanley’s here.’ I thought to myself, ‘Oh Christ, not now!’ He came aboard the plane and told my mechanic, ‘The camera mountings are too tight.’ I’d done a lot of work of that sort and I wanted those mountings to be absolutely solid with the airplane and not all flippy-floppy. When Stanley began his critique, I said to the pilot, ‘Can you start up one engine?’ He fired it up and Stanley literally flew off the plane. As soon as he was out the door, I had them tighten those bolts right up again.”

Often along for the ride, however, was Taylor’s wife Diane, who created a complex notation system to keep track of the footage, much of which was shot on infrared stock. “In particular, the plates used when Slim Pickins rides the bomb down to the target at the end. It would have been impossible otherwise.”

Taylor’s airbourne expertise was in part informed by his service during World War II.

In November 1939, he joined the Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve “and did what was supposed to be a three-year photographic course in 16 weeks.” Taylor distinguished himself with six years of wartime service as an officer and operational cameraman. He was trained to fly as a mid-upper gunner in Lancaster bombers, but his primary mission was to photograph the targets of 1,000-plane nighttime raids over Germany after the bombs were dropped. “This was requested by Winston Churchill, and my material was delivered to 10 Downing Street for him to view. He was keen for the public to see what our lads were doing. I did 10 of those operations, including raids on Cologne and Dresden. On the opening of the second front, I took a small operational unit of cameramen to cover every kind of news story, including the [liberation of the] concentration camps and the [signing of the] armistice. You may ask how these experiences helped to prepare me for my film career. Well, they certainly made me tougher.”

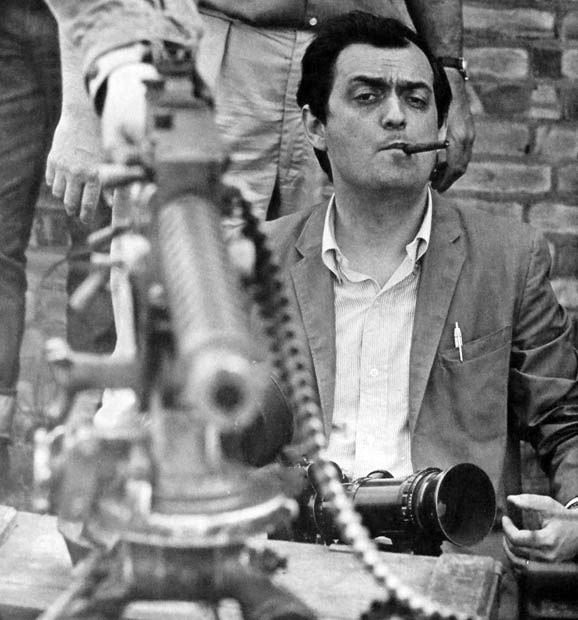

Strangelove’s documentary-style combat footage — depicting U.S. Army forces storming the fortified Burpelson Air Force Base to capture deranged General Jack T. Ripper (Sterling Hayden) — were largely shot by Taylor and Kubrick themselves. “Stanley could handle a camera, so I told him, ‘For all this war stuff, we’ll both put on battle dresses and both have Arriflexes and we’ll just go into it with the men. We’ll film it just like combat cameramen.’”

To give the scene an extra-gritty feel, Taylor ordered “a lot of special film stock that was not fully panchromatic and originally used by the military for copying documents. So it was very contrasty and I only later found out how slow it was — the information I had was completely wrong. But the scene looks great.”

“Stanley was difficult to control since he had his own very strong ideas on photography! But I managed to keep him happy with all my American and British text books in my pocket.”

Taylor added that “Stanley was difficult to control since he had his own very strong ideas on photography! But I managed to keep him happy with all my American and British text books in my pocket. He was a frustrated cameraman with immense talent. I sometimes felt as if his hand was on the brush and I was the paint coming off it!”

Though Taylor and Kubrick butted heads on Strangelove, the director recognized the exceptional work that was produced through the collaboration, and asked the cinematographer to shoot his next feature, 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968). “I didn’t want to do it, but Stanley asked me to do three weeks of work before principal photography began, and I had the time, so I agreed,” Taylor said. “Well, I went to the studio to look at things and Geoffrey Unsworth [BSC] appeared. He said, “Stanley’s told me to come see you because he wants me to see what you’re doing.’ Well, I had no idea that Geoff was already set to shoot the picture, but I told him, ‘If you don’t mind coming to see me, I‘m happy to see you.’ Now, I thought that was a rotten thing to do to Geoff, but that’s the way Stanley was.”

During a career behind the camera that spanned five decades, Taylor also photographed such feature films as Repulsion, The Bedford Incident, The Tragedy of Macbeth, Frenzy, The Omen, Star Wars — Episode IV, Dracula and Flash Gordon.

You can read our complete 2006 profile on Taylor here.

The cinematographer died on August 23, 2013 at the age of 99.

If you enjoy archival and retrospective articles on classic and influential films, you'll find more AC historical coverage here.