Rocky IV: A Photographic Dazzler

Bill Butler, ASC discusses how to shoot a Rocky movie, be it in the snow or the ring.

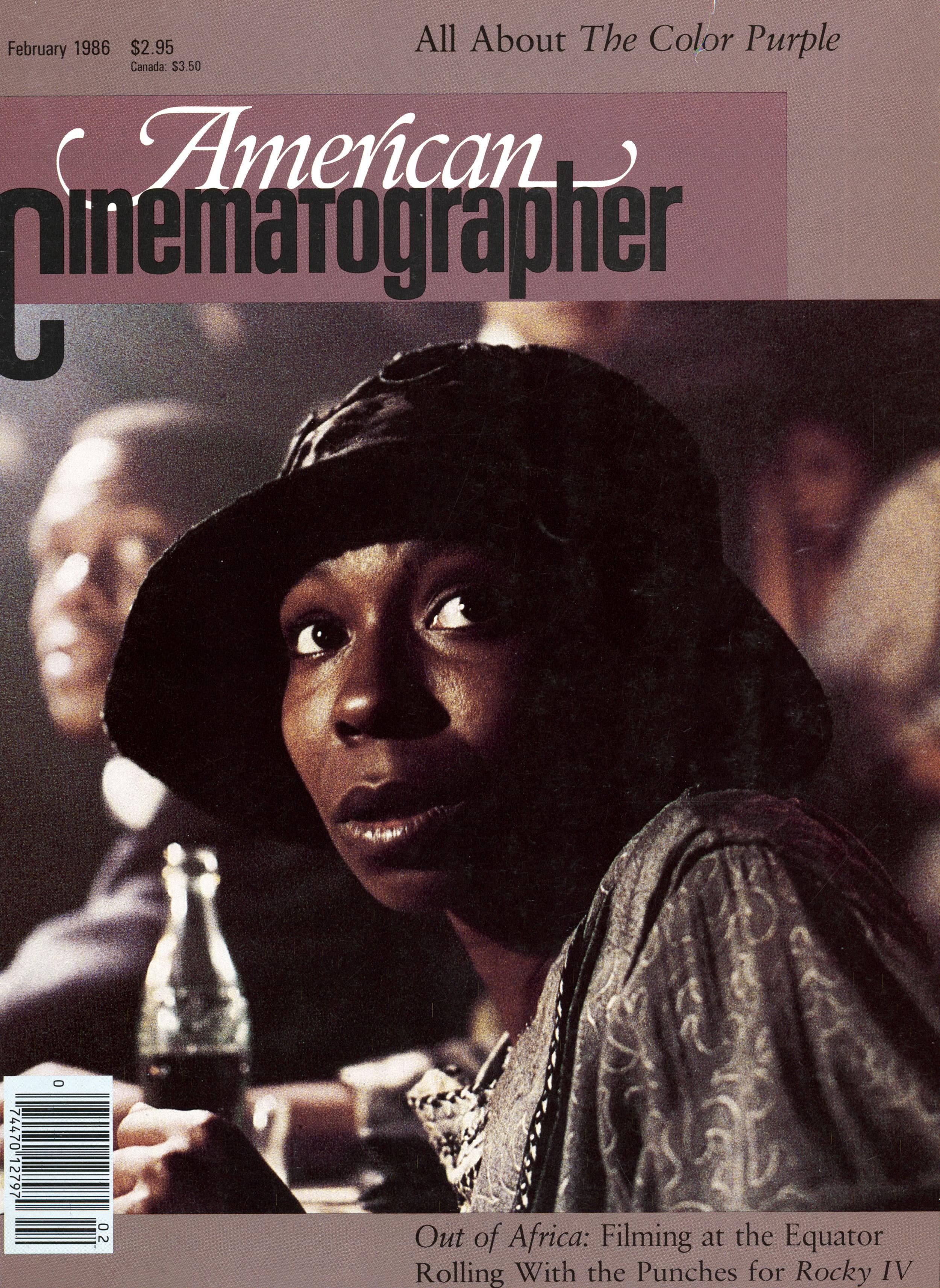

This article originally appeared in AC's February 1986 issue. For access to our historical archive, which houses more than 105 years of essential cinematography coverage, subscribe today.

Remember that boxing scene in Rocky III where Clubber Lang (Mr. T.) is pounding the champion with blow after blow? His fists strike with the driving force of sledgehammers. Rocky is a solid brick wall beginning to crumble. A vicious blow jolts the champ and sends a spray of sweat flying in all directions.

Rocky is like the Titanic after it hits the iceberg. He has met his fate. The only thing left to do is sink. But, there’s a faint glimmer in Rocky’s eyes. It’s a very personal thing that passes between the actor and the audience. If you blink you miss it. Then, Rocky asks a taunting Lang, “Is that it? Is that the best that you can do?”

Now, Rocky fights back. The tide turns in a flurry of images and sounds, while the familiar, upbeat title music signals the audience that hope springs eternal. People start cheering and encouraging Rocky. It happens in every theater just like it is part of the script. The audience couldn’t be more involved if they were in the cast. That’s the magic of movie-making.

So, what is the answer if you are Bill Butler, ASC, and Sylvester Stallone asks you to do it all over again with Rocky IV?

Any hit movie is a small miracle. But four times? It’s like catching lightning in a bottle. How does a director of photography approach shooting a sequel, of a sequel, of a sequel? Rocky has already broken all the rules about sequels. They were once thought of as pale imitations. But, Rocky II, if anything, was more exciting than the original, and box-office revenues doubled. Rocky III also exceeded the success of its predecessor. And now comes Rocky IV.

What keeps people coming back for more of Rocky?

We discussed that question with Butler, who also filmed Rocky II, and Rocky III. (James Crabe, ASC shot the original Rocky.) Butler believes that the Rocky character created and depicted by Stallone represents the quintessential American. “If you believe that any odds can be overcome by working and fighting hard enough, Rocky has a special meaning for you,” he answers.

There are certain common threads that are part of the fabric of each succeeding generation of Rocky movies. For example, for drama, there is a repetition of Rocky’s explanation to Adrian where he tells what being a man means to him. that’s the bottom line; it is the reason Rocky answers the bell when others might quit.

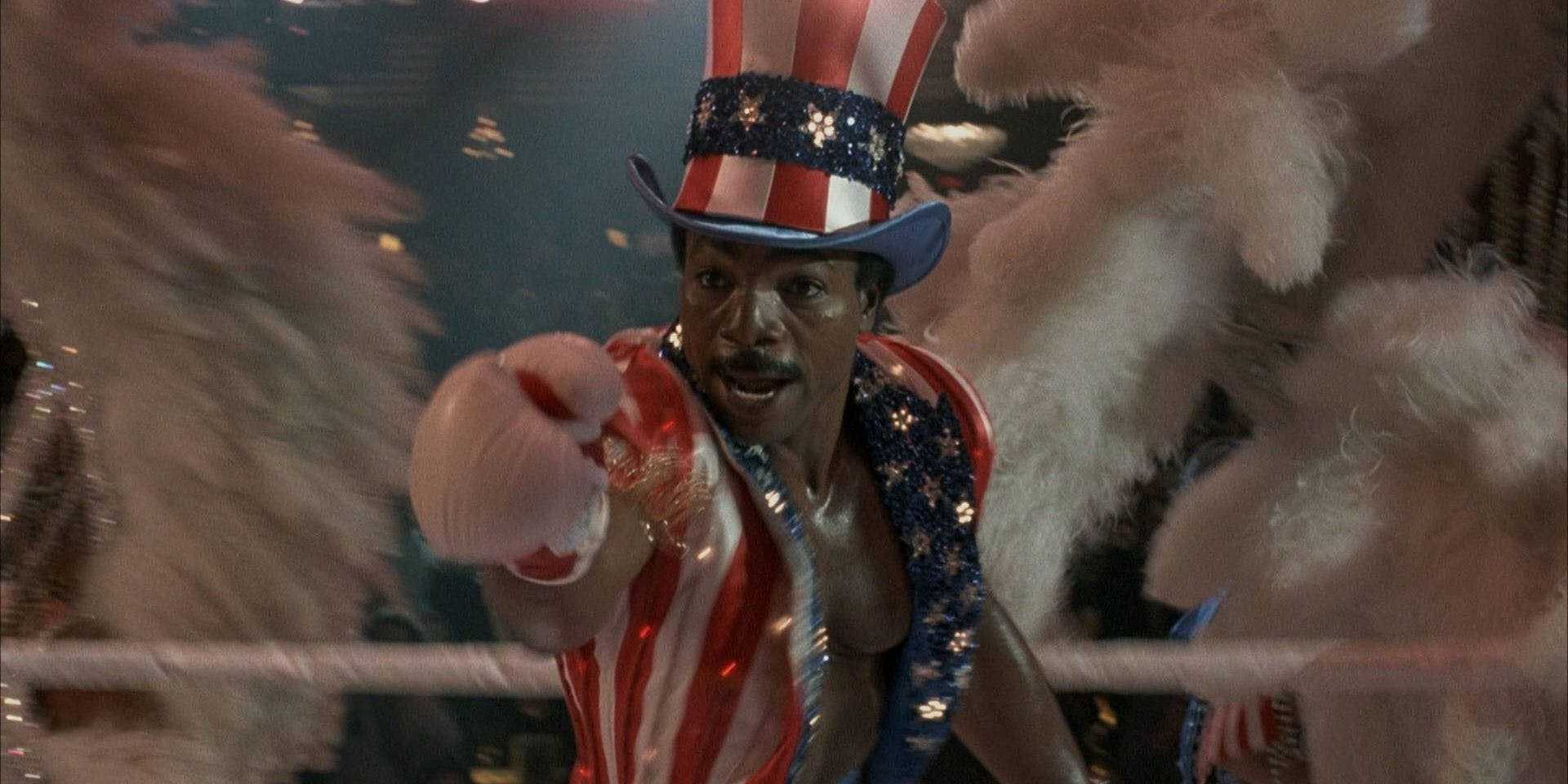

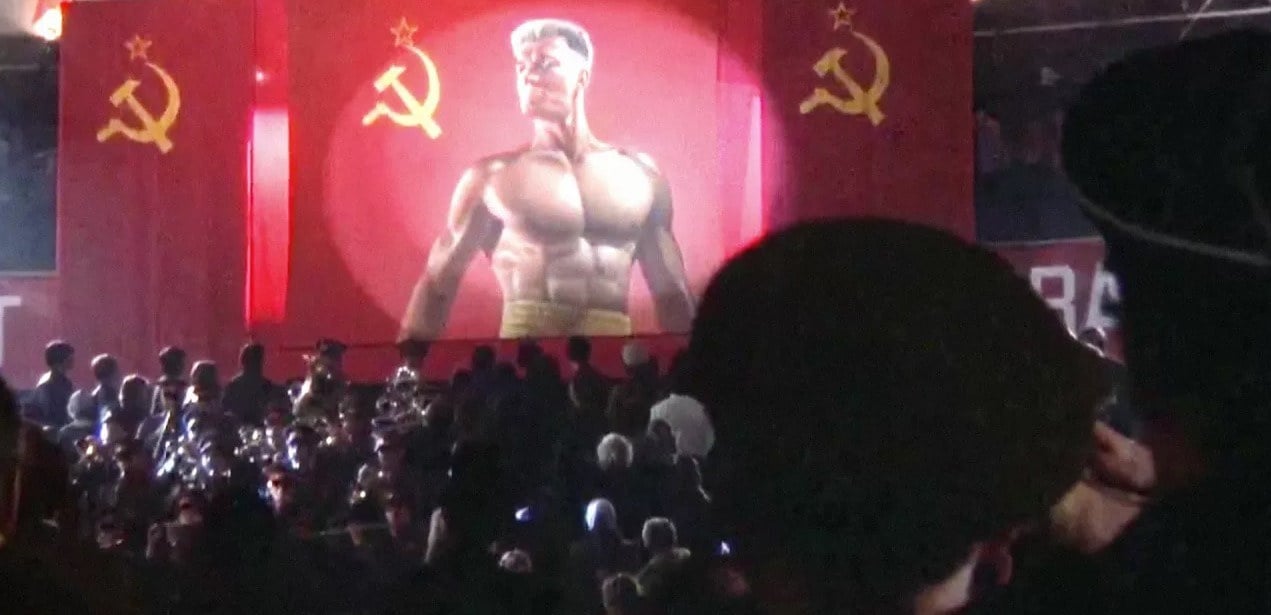

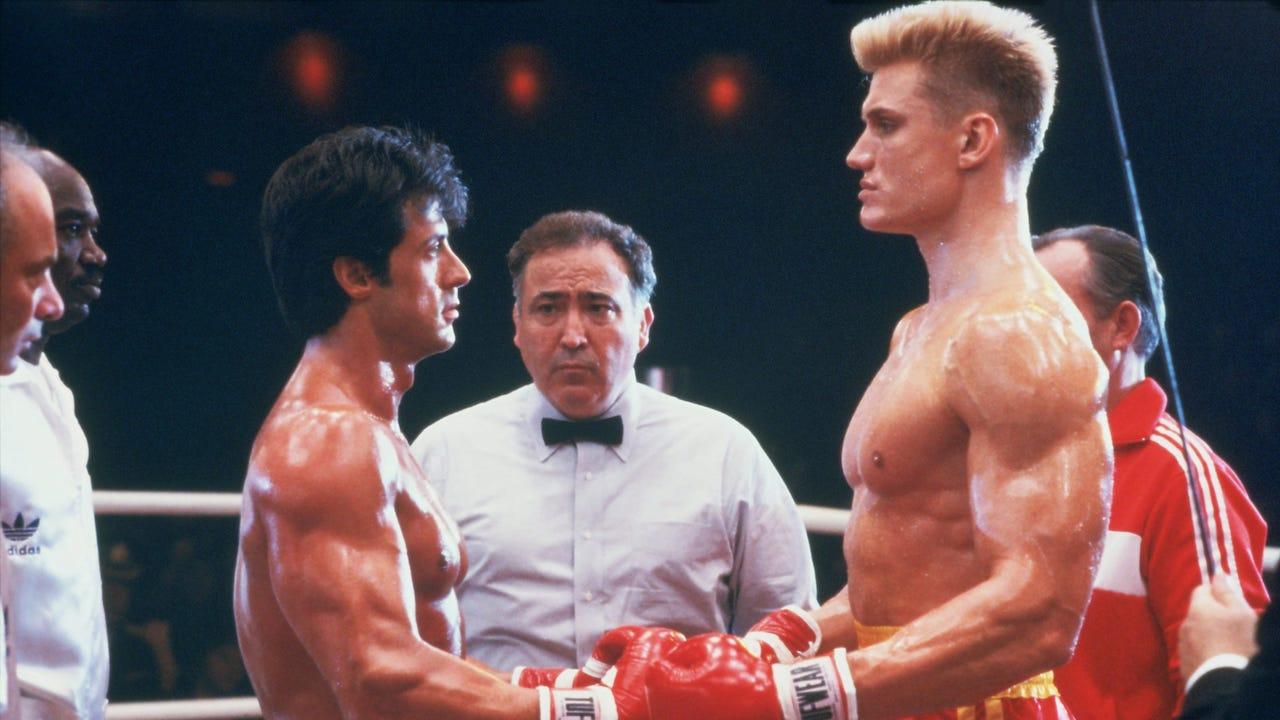

Rocky IV is an MGM film, written and directed by Stallone. It was shot at practical locations in Canada, Wyoming, Nevada, and in areas around Los Angeles. Production was also done at MGM studios. The story pits the Stallone character against a bull of a Russian fighter, who humbles Apollo Creed and draws the aging champion once again out of retirement. The Creed fight is filmed in Las Vegas at the MGM Grand Hotel. The battle between Rocky and the Russian champion is set in the U.S.S.R. and filmed in Vancouver, British Columbia.

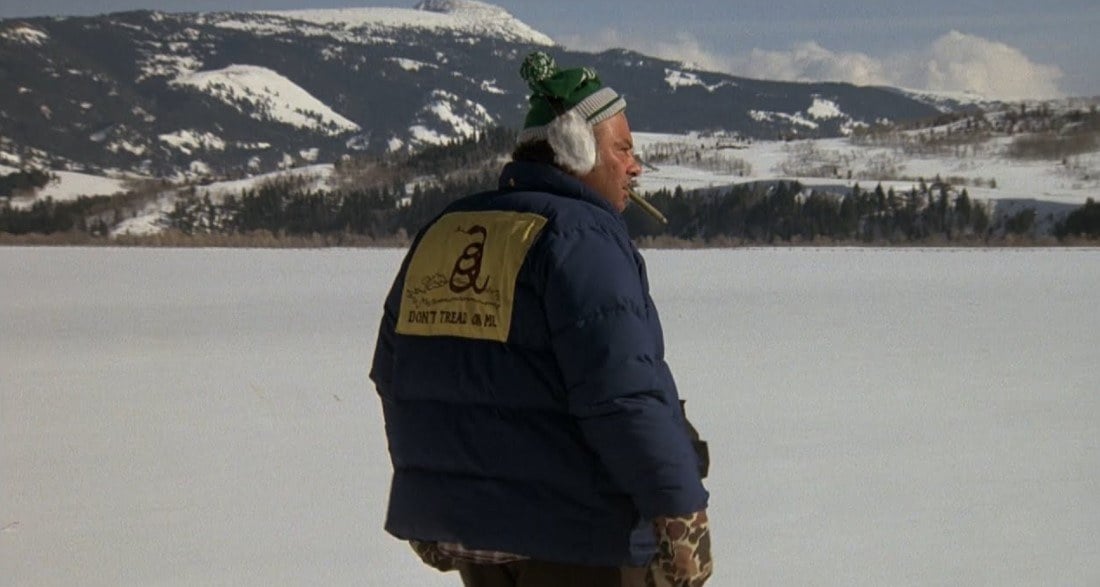

There are winter training sequences shot at Jackson Hole, Wyoming, where night temperatures dipped to 10 degrees below zero. Butler filmed Stallone running up a frozen mountain at the 11,000-foot altitude with heaters on the camera, shooting from a helicopter.

“It was bitter cold,” Butler remembers. “The snow was two to three feet deep on the flat. You couldn’t walk without snowshoes.”

Seeing Rocky run up that mountain in the bitter cold makes a real story point. Rocky’s opponent is an unfeeling machine who relies on science to build his body. The champ depends on a reservoir of raw courage.

For the winter sequences, Butler drew upon experience, and a cold-weather wardrobe, which he collected early in his career when he shot title footage for The Fox in Canada. “The first rule,” he says, “is to keep yourself warm. If you aren’t properly dressed, you get cold and you can’t function.”

More experience: Never take a camera or film from a warm room into the cold outdoors. “The last thing you want is condensation to form on your lens elements,” he cautions.

Camera equipment was generally stored in a truck where a single light bulb provided enough heat in the closed interior to keep the temperature around 32 degrees Fahrenheit. The same was true of the film. “It doesn’t mind get¬ ting cool,” he says. “Just don’t let it freeze, because then it can get brittle.

“The biggest problem we had was with batteries,” he comments. “The colder it got, the less charge the batteries held, and the more we had to recharge them. If you are going to shoot in this weather, plan to bring many more batteries than you would normally use.”

The footage filmed in Jackson Hole and Vancouver helps to establish the setting and adds production value. However, Butler says that the real secret behind the allure of the Rocky movies is no secret at all. “The energy comes from Stallone,” says Butler. “All the time he is training and working to be Rocky, he is pushing himself and everyone around him to excel, and this energy comes across on the screen.”

During location scouting, Butler remembers flying from place to place with Stallone on a private jet with a video cassette recorder on board. They went through the Rocky films time after time until the smallest nuances were etched in both men’s memories.

In a lot of ways, the look is the same as the previous Rocky movies. “Continuity is important,” Butler explains. The audience comes to a Rocky movie with some expectations that have to be satisfied.

But, there are also differences. The visuals are more stylized; there are many more intimate shots on faces, and Stallone calls for lights glaring into the camera, and the use of star filters and red gels in fight scenes.

“He knew exactly how he wanted it to look,” says Butler. “My job was to give it to him. I think we had very good rapport.”

Where does the ability to give a director the images that he or she envisions come from? Is it something you are born with, or do you acquire it with experience? The answer is probably a measure of both. Butler has somewhat of an uncommon background for a director of photography. He studied electronics at the University of Iowa, and started his career working in local television, in Chicago, where he won an Emmy for electronic photography.

Butler began shooting film with William Friedkin, who was a director at WGN-TV. That led him to Australia, where he shot a “quickly forgotten film” called Adam’s Woman, and then on to Hollywood. His early feature film credits include Rain People and The Conversation with Francis Coppola, Good Times with Friedkin, Jaws with Steven Spielberg, and One Flew Over The Cuckoo’s Nest with Milos Forman. Add a couple of Emmy Awards to the mix for several made-for-TV movies, Raid on Entebbe and A Streetcar Named Desire.

Butler shot Rocky IV on Eastman color negative film 5247 and Eastman color high speed negative film 5294. He used the latter for all interiors and night exteriors, which accounts for the major part of the visuals. He rated the high-speed film for its recommended exposure index of 400, however, since he was working with Golden Panaflex cameras and a 200-degree shutter, he effectively gained a quarter of a stop.

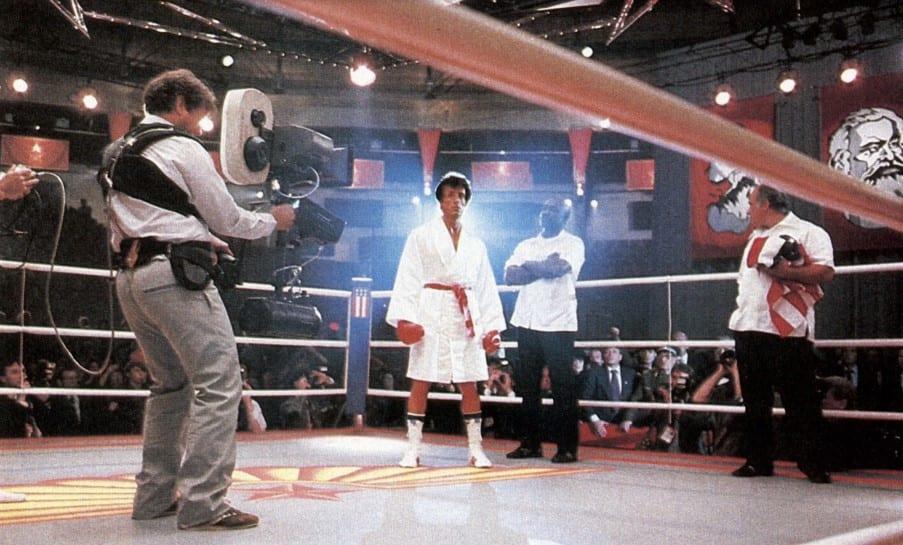

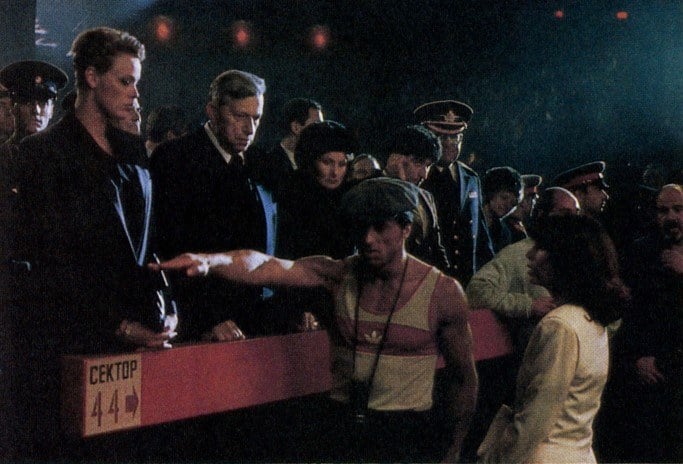

The big fight between Rocky and the Russian was filmed at an arena in Vancouver for a number of reasons, among the biggest being that this is genuinely cold country and people who came to see the filming were dressed appropriately. That was part of the illusion of being in Russia.

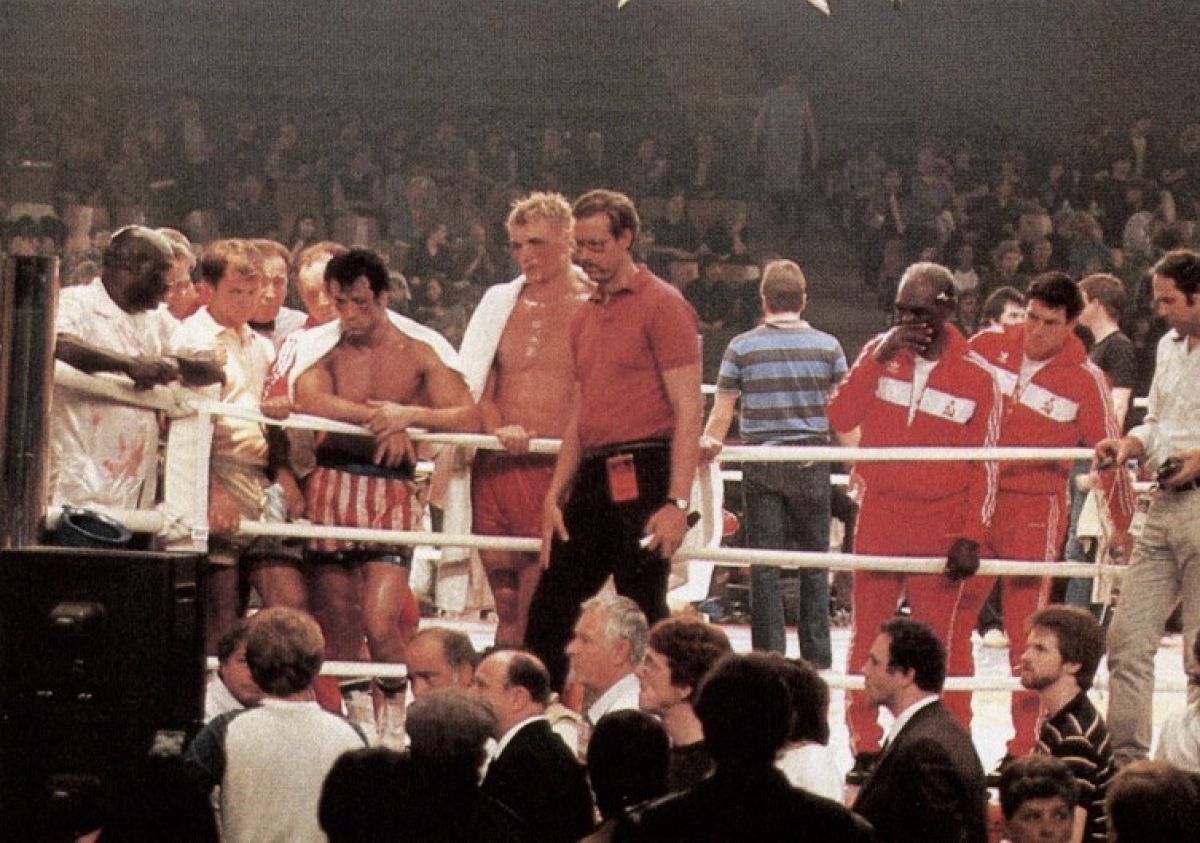

Butler covered the fight with eight cameras. Three were handheld at ringside. These were passed off as news cameras in the film. The other five cameras were maybe 30 to 40 feet back from the action with 250mm lenses providing a capability for zeroing in from just about any point of view.

Most of the light came from overhead fixtures, and it was hot and glaring just the way the audience knows that it looks in a real fight, Butler explains. No one complains about heat in this kind of sequence. They want to sweat, and the hot lights help to keep them warm.

The problem is that all of that overhead key light - maybe 200 or more footcandles glaring down - would have created harsh facial shadows. To compensate, Butler hung two pipes on opposite sides of the ring with a string of soft lights on each. These provided fill light in the ring at about eye level, and also spilled onto the faces in the first io to 15 rows of the arena.

Butler wanted an aperture of at least stop T-4 for depth of field, and the 400-speed film and 200-degree shutter gave him more than enough latitude. “This film looks beautiful when you expose it properly,” he says.

Butler says that there are times when he might choose to push the exposure latitude of the fast film to achieve a specific purpose or look, i.e., a night exterior, or for a shadowy interior. However, for Rocky IV, he wanted a full negative with sharp, crisp images, although he did use LC2 filters to slightly desaturate colors.

In fact, with the overhead key, most of the lens apertures were set at T-5.6 or T-6.3, depending upon the camera angles and relative positions to the lights. The level of light did fall off once you got past the first 15 or so rows, however, that was by design. The shadows masked the five cameras back in the crowd.

At first, literally thousands of people jammed the arenas in Las Vegas and Vancouver filling every seat during the first days of filming. “The crowds were marvelously responsive at both fights,” says Butler. “There were no cues. They just acted as though they were at a real fight.”

Strategy for shooting the Las Vegas fight, which was staged at the MGM Grand Hotel, was pretty much the same except that the fight was considerably shorter, and only five cameras were used.

Both fights were painstakingly choreographed just like a ballet. Every punch and reaction was carefully planned and rehearsed. “We filmed the fights sequentially,” says Butler, “though, of course, we had to work in comparatively short takes.”

Butler learned while filming Rocky II and Rocky III that he needed operators and assistants with the razor-sharp reflexes of sports photographers.

“As carefully as you plan there are times when you expect to pan left and something unanticipated happens and you need to go right or zoom instead,” Butler explains. “Maybe an actor slips and you want to catch the expression of surprise on his face, or a punch comes from an unexpected direction.”

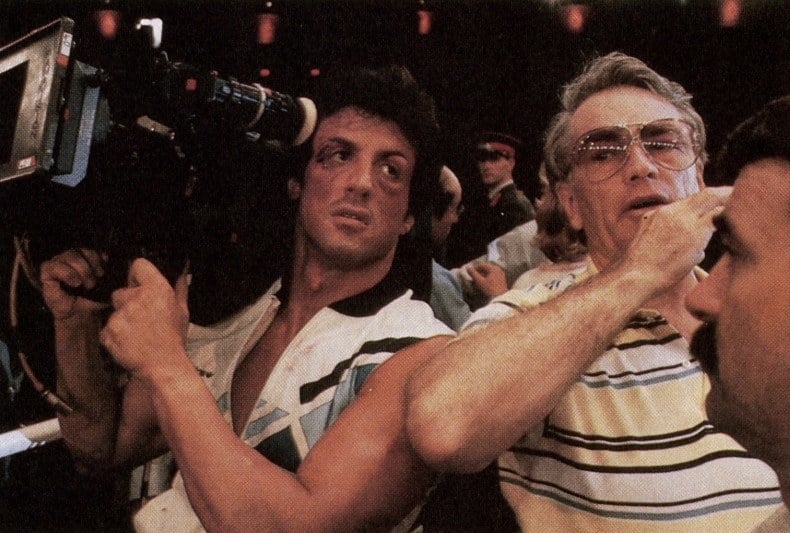

As he did throughout the film, Stallone had video taps on three of the cameras during the fight scenes, and there were separate feeds to tape recorders. That was one of the reasons why Butler used only Golden Panaflex cam¬ eras rather than older models.

“Even with the tap, we could always see what was happening in the viewfinders,” he says.

Stallone didn’t wait for dailies to see if he was satisfied with each day’s shooting. He generally looked at the video on the spot, and if he didn’t see what he wanted, they shot more.

This approach does have some detractors as it can be time-consuming and affect the pace of production. However, there is no arguing with success. Butler believes that the fight scenes will stand up with any, and, as he points out, Rocky IV finished shooting ahead of time and under budget.

Since all eight cameras (five at Las Vegas) were rolling from slate to cut, Stallone and editor Don Zimmerman, who also worked on Rocky III, had a tremendous amount of footage to work with during post-production.

Most of the rest of Rocky IV was shot with two cameras, and Stallone always had a video tap on both. Multiple cameras improved coverage, and gave the editor more to work with, and also saved time.

The two big fights were probably the biggest photographic challenge, but there was also the problem of the snow. “We were shooting in Jackson Hole and Vancouver because of the snow,” says Butler. “Obviously, our job was to come away with beautiful snow sequences. We wanted the audience to feel the cold.”

Nature cooperated by providing a major storm for the crew to shoot in. “You can never duplicate a real snowstorm on a backlot,” says Butler. It’s easy enough to shoot believable snow. “Just expose for the snow,” he exclaims. “It’s not even a problem on medium and long shots where faces aren’t discernible anyhow. A silhouette is acceptable and believable.”

But, how about closeups? If you use an arc or reflector for fill on faces, you can change the exposure enough for the beautiful, fresh, white snow in the background to turn a hint of gray. Butler handled this by placing nets and scrims just far enough behind actors’ heads to be off-camera. This reduced the glare and allowed him to use a little fill light on faces.

The result: The flesh tones are perfect, facial features are discernible, and the snow is milky white. There are various ways to solve this kind of a problem. However, Butler says that the key to the solution is understanding the emulsion that you are shooting with and what it can do.

“Instinct is knowledge that you don’t know you have,” he says. “If you know exactly what your film will do at different light levels, you can take some chances. People talk about painting with light, but l think that the emulsion is the paint that you lay to the canvas.”

The snowstorm was one extreme where Butler’s instincts or knowledge of the emulsion paid dividends. The medium-speed emulsion for 5247 film, which he used for shooting daylight exteriors, has a tremendous range of exposure latitude! “This film does give you an ability to work one or even two stops over or under without noticeably losing sharpness or increasing grain,” he says.

In situations like this, a variation of a couple of footcandles can cost you a stop. “We are using light meters today which are nothing less than handheld computers,” says Butler. If you know what the film will do in this situation, you know how to light for the scene.

“If you front fill to cover Rocky’s face you erase some of the effects of the drop lighting. In most scenes, the solution is to use a combination of top and edge lighting,” Butler says.

Butler says that when he speaks at cinema schools, there are usually some very specific questions about situations like this. The truth is that there are no catch-all answers. “The most satisfying thing for me in this business is making a really difficult shot so believable that no one knows that you did anything,” he says. “If someone tells me that he or she liked the way that I achieved a certain lighting effect, I think that I must have done something wrong.”

How about Rocky IV? Does it measure up?

Butler thinks about that question for a minute or two. Then he answers, “I believe that people are going to be cheering at the end, and they will leave the theatre humming the song and feeling good.”

For access to all 100 years of American Cinematographer reporting, subscribers can visit the AC Archive. Not a subscriber? Do it today.

Stallone announced in early 2021 that later in the year he'd be releasing a new cut of the movie, titled Rocky vs. Drago. Sadly, there are reports that Paulie's Robot may have been cut from the new version...

Here's the teaser for that.