Storyboarding Key to Beetlejuice Effects

A report authored by a sculptor and puppeteer on the production reveals the tricks and techniques used to conjure the film's iconic in-camera effects.

This in-depth look at the making of Beetlejuice first appeared in American Cinematographer's December 1988 issue. For full access to our archive, which includes more than 105 years of essential motion-picture production coverage, become a subscriber today.

Set Photos by Jane O'Neal and James McGeachy

“About two yeJanears ago, I was called by director Tim Burton to storyboard Beetlejuice, and the rest is motion picture history; the end," says Alan Munro, the visual effects supervisor on the successful '88 summer film by that name. On screen it may be history but the details of how the many varied effects came together through the combined efforts of such notable effects people as Robert Short, Pete Kuran, Chuck Gaspar and others does deserve a flashback.

Munro previously worked as art director in the effects department at Cannon Films on such pictures as King Solomon's Mines, Alan Quatermain and The Lost City of Gold, and Invaders From Mars, before going on to supervise effects on The Wraith. “Needless to say, we storyboarded for a couple of months, and I rolled gag mania into the film. I wondered each night if they really would do it. Looking back, we actually accomplished everything that was committed to paper. Very little was cut, and most of that was cut for the right reason, namely story.

“At first, I wasn't supposed to coordinate effects, but Tim and I had some mutual loves, most notably Karel Zeman films, obscure films that have a strange woodcut look and style. They're a combination of live action and cut outs. They are crude and funky, but they work on a level that is consistent, creating their own universe not only in aesthetics but internal logic. In Beetlejuice, we tried to create a rule book of internal logic and stick to it in terms of how things were presented. We were always toeing the line between real and unreal, serious and not serious, scary but at the same time funny, always doing a balancing act of what seemed to be opposing notions."

The effects work in Beetlejuice is characterized by an emphasis on in-camera effects and matter-of-fact presentation. "I'm a really big fan of early British films that have some beautiful looking stuff that was done in camera,” Munro noted. "Times being what they are, however, there's not a lot of call to try those things. This was our chance to try some and prove that it was also feasible, financially, to do this kind of work. There were about a half-dozen shots that we wanted to do this way, but there were a lot of unconvinced people in the production. My first task was to go off with the cameraman (Tom Ackerman) to do sort of a $1.98 version of some mirror shots and prove that we could get away with stuff that looked extremely klunky on set, but were very acceptable on camera.

"In Beauty and Beast, the French film, there is a scene where a bracelet transforms into a rag. It is presented in a very matter-of-fact manner; the person drops the bracelet, and the camera whip pans down to focus on the transformed object. Of course it was achieved by simply dropping the bracelet off screen and having some one else drop the other object. The whip-pan covers it. Using this notion, we arrived at the transition of the bannister into the snake, which was just a sculpted piece, rather than doing an effect of the transition. The sculpted piece makes the transition from the normal bannister to the snake body with just a camera pan, along its length, motivated by a hand. It worked, the magic of the shot being its matter-of-factness.”

Mirror shots were de rigeur in the '20s, for ghost images. Munro had done some shows at Expo '86 which involved mirror gags. He was intrigued by the possibilities inherent in scenes in which characters disappear. "What it takes is two things: the person who is going to vanish (placed off set), and the real set with the real people; that is, all of those things that aren't going to vanish,” Munro explains. "To make the vanishing person appear solid at the beginning, it's necessary to selectively cut out the light on the real background so that you don't see through the body, and also to position in such a way that one person is not crossing over another person. The first step is not to bring down the light on the character, but to bring up the light on the background. That gives the feeling that you could suddenly see through them, which heightens the illusion."

"The beauty of the mirror shot is that, once set up, the camera is completely free to pan, tilt, dolly, or whatever, because the image is actually there. In the course of these shots, there are some very natural camera moves. If we had tried to do these by the usual blue screen method, we would have had to go with motion control on the set, then motion control match moves later on with the blue screen person. It would have been prohibitively expensive. Just by controlling the light and taking care in planning how we were to stage the shots, we were able to get a result that ordinarily would have been very costly and complicated. The other beauty to it is that it's all first generation film.

"It's basically taking a front surface mirror and placing it at a 45 degree angle directly in front of the camera lens," Munro continued. "The blacked out stage with whatever is going to disappear is at a 90 degree angle and an equal distance from the plane of the glass as the real set. Then, of course, they must be lighted separately. The other critical factor is that the object being reflected has to be flopped, to right hair parts, rings on the fingers and so on. "On one particular shot where the character Barbara is supposed to be vanishing, Adam reaches up and passes his hand through her body. For that I stood by Geena (Davis, who plays Barbara) in front of a light and matched his hand gestures to cast the correct accompanying shadow on her face to heighten the feeling that they are in the same physical place. All of the elements are together on stage, and it's easier than trying to coordinate them at a later date."

To helm the film's vast array of creature and makeup effects, Munro and the production company selected Robert Short. "Bob and I share a lot of ideas about approach, such as always trying to keep things as basic and low tech as possible," Munro said. "Anytime you over-complicate things, you magnify the probability that something will go wrong. By keeping everything simple and straightforward, you not only minimize the number of things that can go wrong, but it's that much easier to troubleshoot any problems on the set. Bob and I both come from the low budget school of thinking, with a scotch tape and rubber band approach to solving problems."

Short is well known for his water related effects, such as the mermaid tail in Splash and the dolphins and cocoons from Cocoon. "No one particular effect offered the most challenge," says Short, "but the sheer number and diversity of effects was staggering." They involve the widest range of the movie magician's art, including shrimp cocktails attacking dinner guests, transformations, headless bodies running around, people sprouting spikes, ripping off their faces or distorting them hideously, giant sandworms, snakes, a six foot beetle, a fly, and a variety of walking corpses and ghosts.

Each effect required a different technique and there was hardly any overlap of application from effect to effect," Short allows. "Budgeting was a best guess scenario, but Alan Munro's storyboards were very precise and showed an excellent knowledge of what it would take to accomplish the effects in terms of camera angles and such. They were very helpful in keeping the budget down.

"Most of the designs were done by either Rick Heinrichs or myself," explained Munro. "Rick had a precise sense of what Tim wanted and would always kind of act as the final arbiter of the finishing touches. Tim would assign either Rick or myself to design a specific creature, be it a transformation, the preacher, charman, or whatever. In a lot of cases I would do the initial design, then Rick would do some refinements, and I might do the final drawings. In other cases it would be exactly the opposite. The only things designed solely by one of us were the sandworm and the snake, which were Rick's."

"One of the things we prided ourselves on," Short relates, "was being able to duplicate exactly the designs given to us from production. At the director's request, certain designs had to be duplicated to the most minute detail to the maquettes." The sculpture staff, including Linda Frobos, Leo Ryn, Kent Jones, and others, often stood by as the maquettes were held up in front of the final sculpture and checked for faithfulness of detail, and to assure that the planned asymmetricalities were rendered appropriately.

"We always took into account some sort of emotion or character that captured the essence of the thing and incorporated that into the sculpture. For example, there is only so much movement that one can get out of any facial appliance, so when it came to creating the degeneration sequence for Adam and Barbara we considered the script's description reflecting utter sadness and integrated that into the sculpture," Short continues. "We've been asked at times why the old age make-up was so stylized, and we remind people that they're not strictly old age make-ups, but a representation of what 'death for the dead' looks like. It's a different state of being than old age. Considering the style and overall design of the film, a realistic old age, ala Amadeus, would have been inappropriate." In fact, Short's crew was planning a realistic approach but as soon as they started sculpting, the director said he wanted a "plucked fruit" look, which began a whole new design process.

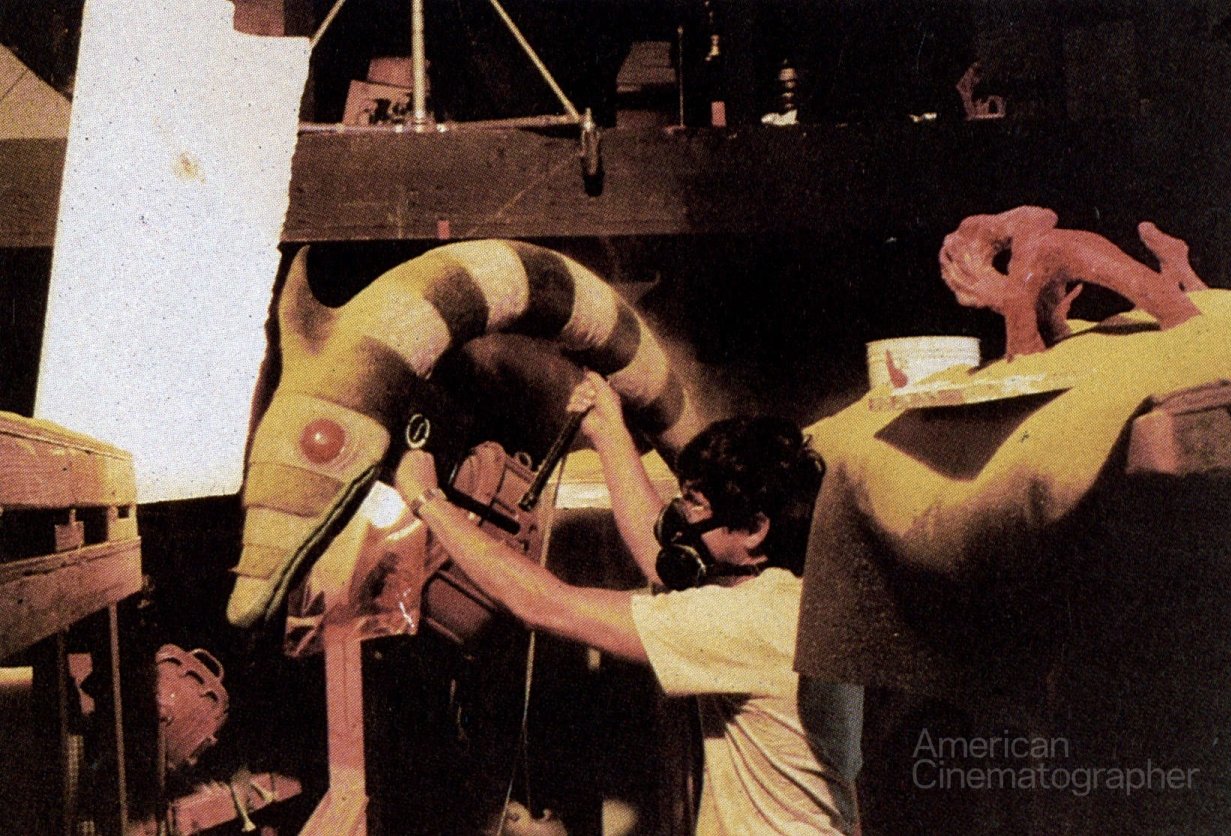

The look of everything in Beetlejuice was very well planned, as Munro points out. "It was first and foremost an exercise in style. We tended not to compromise the aesthetics in order to accommodate little things like the mechanics." This sometimes caused headaches for Short and his crew. "Tim insisted, for example, on the sandworm having almond shaped eyes. This made it difficult to mechanize, because when the eye moves, it leaves gaps between the eye and the socket. The mechanics had to make a flexible backing which always kept the eyeball pushed against the socket. Of course the eyelids became more complex as well, because the eye ball was always changing shape in relation to both the lids and the socket."

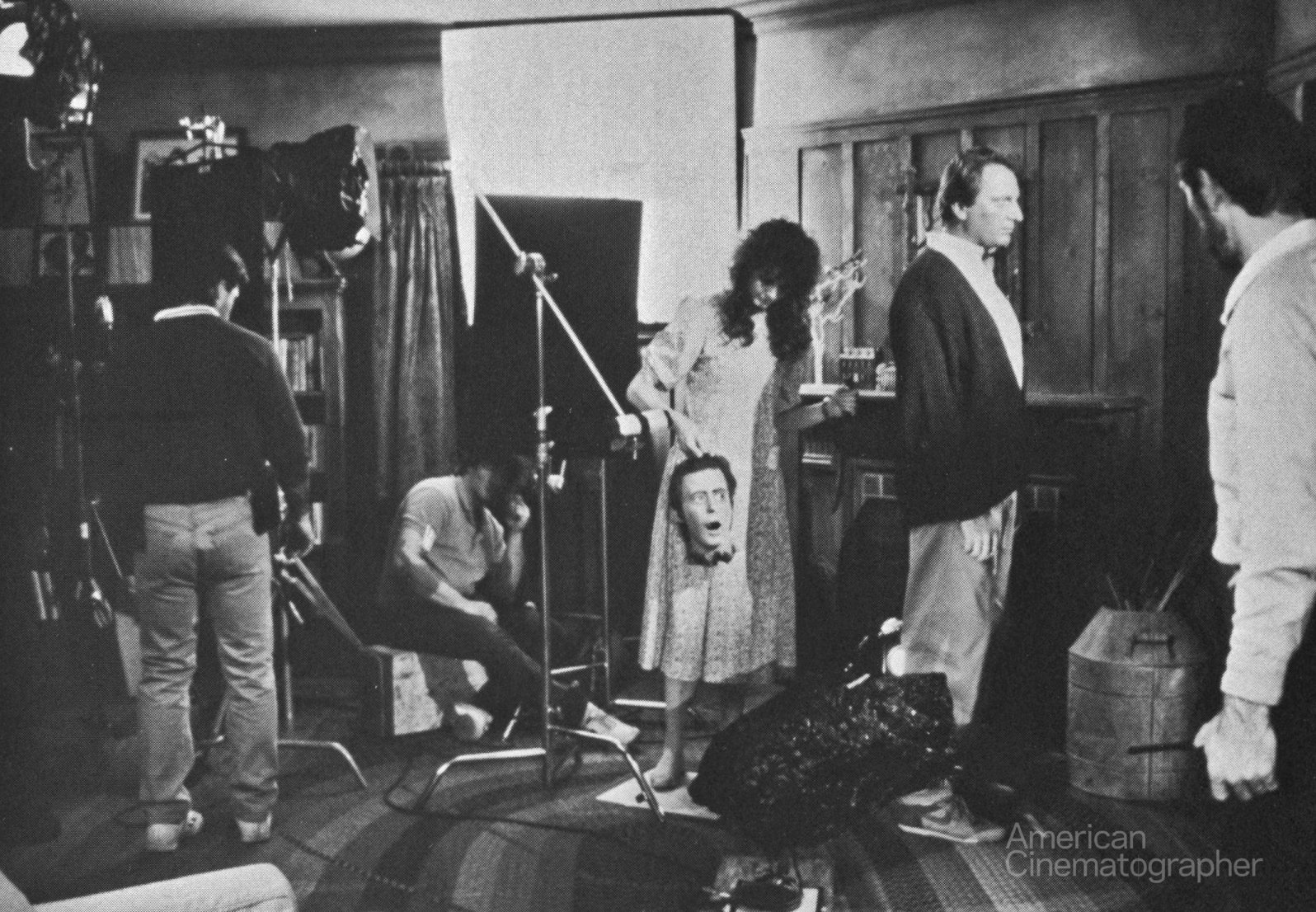

In one sequence, Barbara stands holding the severed head of Adam, (played by Alec Baldwin) above his body, which lies on the floor. Once the ghostly pair realizes that they are invisible to the humans, Adam opens his eyes and talks to Barbara. Then, as they realize that the attic door is unlocked, Adam's body jumps up, and runs, still headless, out of the room and passes the mortals on the stairs. The body runs into the attic, slams the door and holds it shut. Later, Adam's body re-enters the study and puts his head back on.

"The sequence could very well have been a very expensive series of opticals," Short recalled. "We approached it with the understanding that we would achieve the overall effect live, on stage, without having to compromise its impact. It was agreed that we would create the talking head suspended in midair by means of a foreground piece that replicated the front of the desk in the background." The piece was rendered sufficiently out of focus to push it into the background. "Alan created the foreground piece, while we made the foam latex appliance which attaches to Alec's neck to complete the illusion of a stump.

For the body, running, two elements were created. For shots from behind, we made an appliance stump to be worn by the stuntman, and for front and side shots, a mechanical body specifically in running mode was created. This, in turn, gave us all the elements necessary to create such images as the headless body running through a doorway toward camera, then leaving the frame for a split second, then the stuntman returning to slam the door: hence, the illusion of seeing the body from the front and back in a single shot. The last shot was of the body walking to the desk, picking up its own head, and putting it back on. It could have been achieved by having the stuntman pick up the fiberglass head, but to give it more life we opted for cutting the desk in half to allow Baldwin to place his head on the desk. Then, as the stuntman enters and blocks our view for an instant, Alec hands the stuntman a replica of his own head. He in turn, places the glass head on the appliance stump."

"The sand planet was another one of those situations where everyone had assumed that the entire sequence was going to be an optical," explains Munro, "but being a fan of in-camera effects, I very much wanted to do it as a forced perspective miniature and shoot it all on set. I built a ¼ scale model of what the miniature would actually be, then photographed it with Barbie dolls and proved to everyone that you could get a decent frame size with a very small miniature set. The sand planet, at its monumental height, is only about 12 feet deep and about 25 feet wide with rocks that ranged from about seven feet to maybe one or two inches in the background. The back was a small eye, about 18 feet high and 30 feet wide. Given those restrictions, there is still only one shot in the main sand planet sequence where the people are composited into the shot, that being the wide shot of the worm chasing them across the dune."

"The afterlife sequences presented us with a chance to create an array of gruesome but likeable characters that would become a combination of puppets and live action," says Short. Some of the victims were a relatively easy assemblege of props, such as the camper with the rattlesnake, or the skindiver with the shark on his leg. Others involved prosthetics, such as the man with the chicken bone protruding from his throat and the open heart surgery patient complete with tools still in place. The remaining three, the Charman, the Hunter, and the magician's assistant, were a more complicated combination of live people, prosthetics, puppetry and specially modified furniture. Except for the Charman, the appliances and puppets were constructed long before the actors were cast for the parts. This necessitated some improvisation; the man with the bone in his throat, for example, actually wears the appliance upside down. "It fit better that way."

For the two halves of the magician's assistant, the ragged edged stump was sculpted over a manikin - a male manikin at that - rather than a life cast, and was used for both halves. The actress who played the bottom half was lying flat on a platform that extended through the couch and wore a foam rubber stump that simply rested on her hips. For the top half, the actress was sitting in a hole in the couch and a slip latex cast of the ragged saw edge was tucked under the edge of her blouse and dressed over the hole.

Short continues, “The most memorable of the characters was Harry, the Haunted Hunter (as the publicity dept, named him; during production he was most commonly known as Pin Head), a man with a shrunken head. This puppet connects an armless torso from the waist up with a live actor to create the illusion of a living thing. Only a few simple mechanisms were required to give the puppet life. Of the seven characters in the waiting room, the most complex was the Charman."

"For the flattened messenger," Short continues, "we created one body that would accept the real actor's head (with appliances) standing behind, as well as accepting a fully remoted head whose eyes and mouth moved. The real actor was used for straight-on shots while the radio-controlled head enabled the crew to pick up shots from the side to establish his thickness of only a few inches. In sequences such as this, one cannot express enough the need for accurate storyboards.

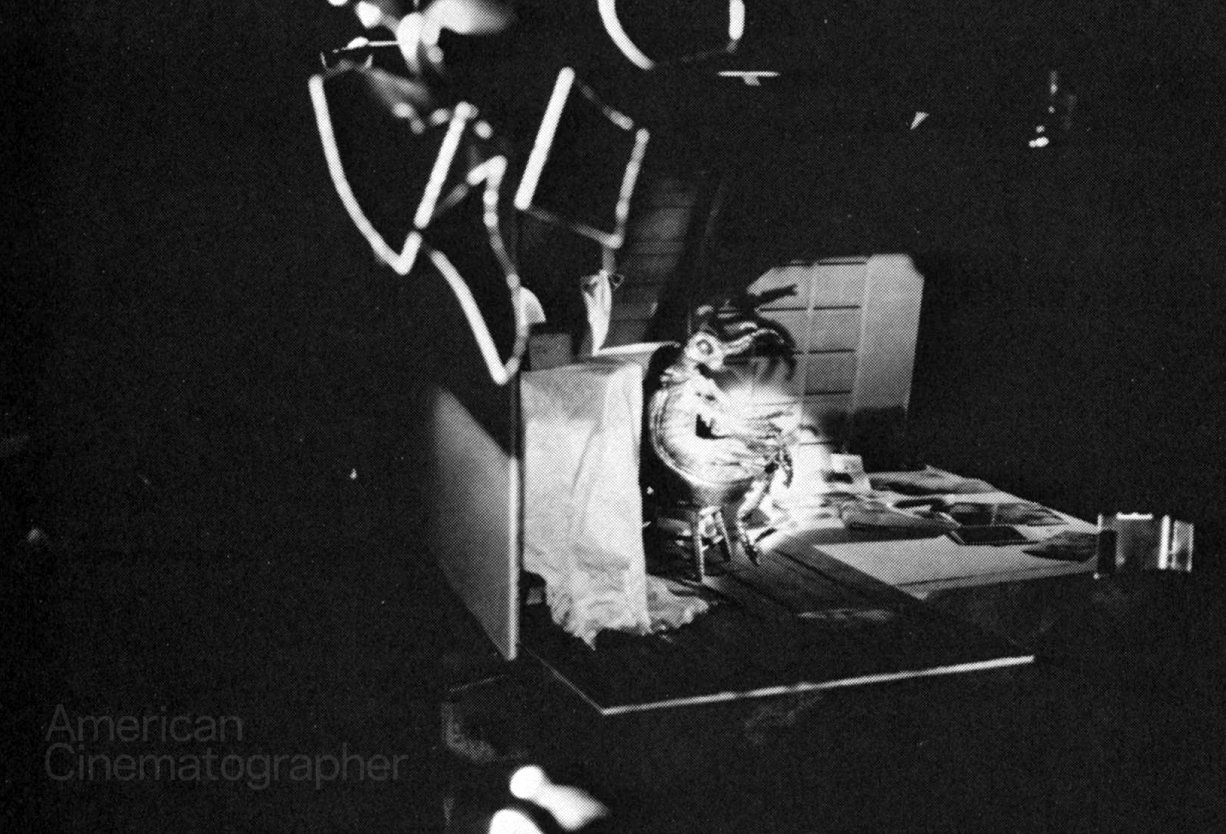

“The typing secretary skeletons were plastic anatomy class skeletons revamped with simple joints so they could be manipulated as rod puppets. They were painted and photographed under ultraviolet light. Each skeleton was given its own UV lamp on which the film could not focus perfectly and this gave us a very ghostly image."

For Juno (Syliva Sidney) Short's crew created a foam rubber appliance fitted with a tube through which smoke could be blown. "This presented a problem in the office, when temperatures soared to nearly 100, making it extremely difficult for the make-up technicians to maintain the seam lines," Short says.

"With the football players we found ourselves toeing the line between gross and offensively gross," Munro remarks. "That was part of the notion behind making them bright blue, to sort of take the edge off. They were cast late in the production and their generic appliances were made up well in advance. The body pieces were attached to the uniforms and actually became a part of the costumes rather than being glued to the actors' skin."

Ironically the task which seemed simplest at first turned out to be hardest. The uniforms supposedly trashed during the crash that killed them, in fact were virtually indestructible. Short's crew spent hours hacking away at jerseys and pads with knives, files, machetes and even a chainsaw. One of the best methods of distressing the helmets turned out to be dragging them behind a car!

How to accomplish the scene in which Adam and Barbara distort their faces into monsters was the object of considerable discussion. Munro explains: "The originial intent was to do the scene with clay animation, but one of the shortcomings of this method is that you start at one end and kind of let it go. In this case we had to go from an obvious point A, the live actors, to a very precise point B of the finished transformation, a mask that had already been constructed and shot in live action. So we had to get from one point to another in a specific number of frames. We looked at the possibility of doing them as make-up effects, but we couldn't see a way to use that method for a single master, as Tim wanted. There is also something inherently grotesque about people sticking their hands in the back of their throats and pushing the backs of their heads out, or pulling their jaws apart. We intended it to be shocking, but not shocking in the sense of 'gross.' The decision to use replacement animation was made for aesthetic, rather than economic or technological, reasons.

"The only option we had," Munro continues, "was to sculpt a series of individual heads and shoot them. Tim Lawrence was hired to do this. Aside from the obvious sculpting problems, there was the difficulty of keeping the hair and clothing from chattering. If each statue had its own individual wig and clothing, then in every frame, the hair and clothing would just crawl all over the screen. We worked out a system so that the heads could be moved in and out, but the wigs and clothing stayed in place.

"They were sculpted in roughly half scale, so we had to work out a lighting scheme that tried to be faithful to the set lighting but didn't scream out that they were scaled puppets. That necessitated adding a bit more diffusion and bringing the light level down a bit from what was on set."

Munro describes the process of shooting the fly in the graveyard sequences: All the main graveyard sequences were shot on shallow sets with black backgrounds. We had planned a much more complicated set with slots for puppeteering, but we realized that since the set itself was simply shot against black, the most straight forward way to shoot the fly was to recreate the set and photograph it against black.

"The trick became to concentrate the light on the fly, not on the background. The puppeteers are literally in frame on film, but you can't see them because of their black ninja outfits. We ended up shooting everything at four frames per second and tried to coordinate and time the head and leg action so that it didn't get too frantic. The result is that the fly looks very frenetic."

The film's use of a talking snake is described by Ted Rae, who animated the snake: "The stop motion snake was built one-third scale, in three sections; there was no one whole piece of snake. When the snake comes in and talks to Charles, that's a two-thirds scale puppet, shot at 12 frames per second, to a dialogue track run at half speed and blue-screened into the shot. All of the cinematography has such strong directional lighting that we had to put in shadows. For one shot, we took the matte of the snake and repositioned it, diffused it and used that as the shadow on the wall. We had to do a split density shot because it is going through a shadow within a shadow.

"To get the eye movement on the puppet," Munro continues, "we shot it with blank eyes and rotoscoped the eyes in to get the rapid snake-like eye movement and also have the pupils dilate. If there was ever an object totally unsuited to all the drawbacks of stop motion, the snake is it. A snake wants to move in beautiful, smooth precision. Given those requirements, Rae did an extraordinary job. There are a lot of subtleties, like having the head remain stationary as the body coils up behind it.

"We shot all of the background plates on 35mm," Munro says. "One of the myths in the industry is the use of big format plates, but unless you have a printer that is able to reduce and composite at the same time, what you gain in image size, you lose in extra generations. I haven't found the difference worth the trouble of having another camera and camera crew. One of the reasons things worked out so well from the standpoint of shooting plates was that we did registration tests on the Panaflex Gold and found it to be extremely steady. So, basically, all the plates were shot during principal photography with the same camera we were using for everything else. There weren't any problems with compatibility of lenses and it made it very easy to just tell everybody to stand still. It afforded us the ability to shoot plates as protection in case we decided to spruce it up a bit."

The opening of the movie required a transition from a real town to a model within which there is a very large spider and human hands. According to Munro, "The decision was to try to blend live action footage of the real town and be able to seque into the miniature without being too obvious. The method was to build a section of the miniature in a scale that was considerably oversized in comparison to the final spider and final house. Knowing that the scale portion would be able to stand up to greater scrutiny, we also built a quick forced perspective transition that could be hidden by the tilt of the camera.

A big problem was that real spiders don't perform on command. "Having had previous experience toying with spiders, I knew that we were in for an endless number of takes before we'd get an acceptable result," Munro winced. "We tried everything to get the spider to move on cue: heat, puffs of air, people blowing on them off camera, little wires and sticks to prod them, but, alas, spiders don't want to do anything unless they are damn good and ready."

Munro feels that the optical effect that offered the biggest challenge and yielded the most memorable shot was the Beetleguese head spin. "This was achieved by first shooting Adam and Barbara looking in horror at an empty set. We recorded this on video and, several weeks later when we stood Keaton in front of the blue screen, we used the video to line up the shot and get the scale right. First we shot a clip of the actor starting and finishing the action of the head spin, so he would whip his head to the side, straighten up, pause for seveal beats, then grab his head and pretend to stop it.

"After we got those pieces of film which we also recorded on video, we put Keaton on a turntable on the stage. We centered him up and basically ran him like a rotisserie, spinning his whole body around. We shot at four frames per second, and got about a dozen good revolutions before he got too dizzy. We took the spinning head and rotoed out the rest of his body and shoulders and had an element that was just Keaton's head spinning.

"Then we took the element of Keaton standing and matted out his head in the middle portion of the shot, using his head whip to bring in the spinning element. So we dissolve his real head out and bring in the spinning head which is now running as an element on his old body, and at the end of the shot we quickly dissolve it out as he grabs his head to stop it. The end result is a shot with one continuous motion where he turns, his head spins and he grabs it to stop it in a seamless fashion."

A somewhat similar technique was used to show Keaton's head shrinking at the end of the film. It was achieved by building a couch that had a fixed, headless upper body puppet of Betelgeuse. As Munro recalls, "We had an actor pushed through the couch to give some leg and arm movement and positioned it in the set, so we had a shot that was like any other production shot, with background and other characters, the only difference being that there was a character in it without a head. We then took that piece, went to the blue scene and lined it up at a match point. We then zoomed back with the camera to achieve the head shrink.

"It was a little tricky to set up because zoom lenses don't zoom in a perfectly linear fashion except in one sweet spot in the lens. We had to find that one spot so his head wouldn't be moving up and down during the shot. We knew that we wanted his head to shrink on the axis on the base of his neck so that it wouldn't bob up and down. We didn't want to reposition the head in every frame, for obvious reasons. The magical mathematical formula that we used was to screw around with it for several hours the night before to find the right spot."

All the magical mathematics in Beetlejuice work to perfection, as the continuing popularity of the film testifies.

(The author was a sculptor/puppeteer on the production, and therefore was privy to close observation of the special effects and their creation for Beetlejuice.)