Pop-Up Horror: Production on The Babadook

This in-depth look at the making of The Babadook first appeared in American Cinematographer's December 2014 issue. For full access to our archive, which includes more than 105 years of essential motion-picture production coverage, become a subscriber today.

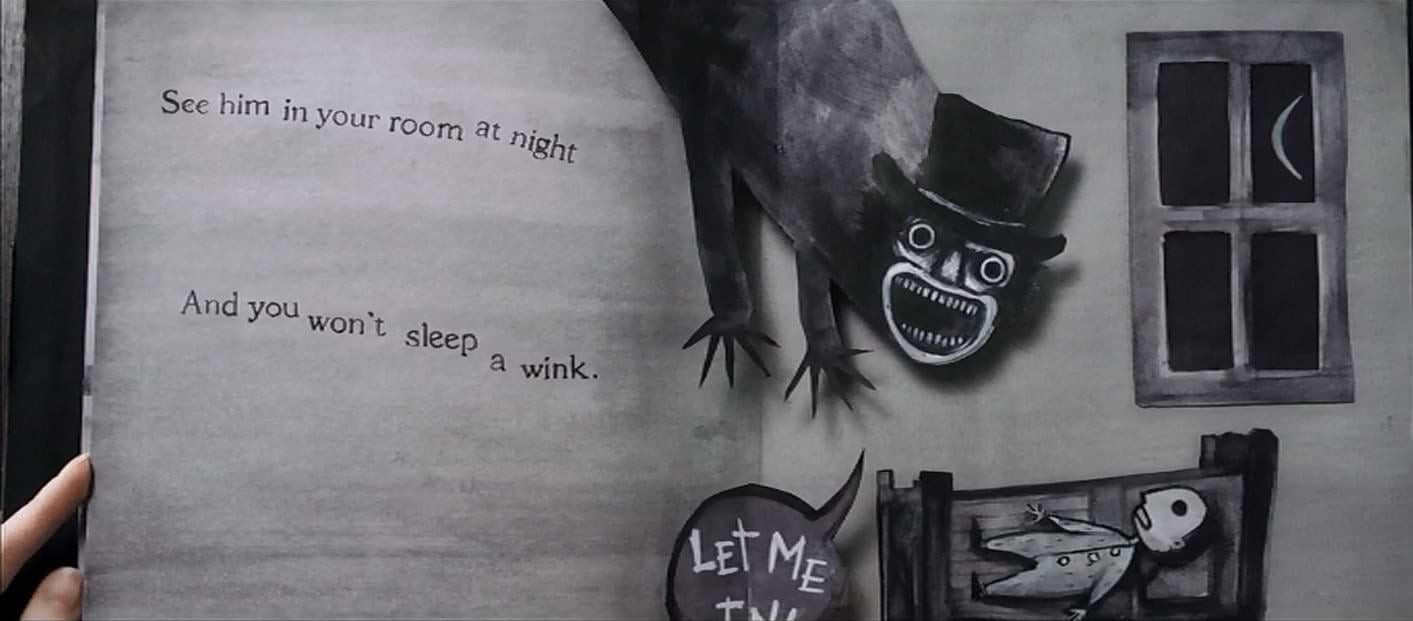

The death of her husband years ago has left Amelia (Essie Davis) psychologically paralyzed and her young son, Samuel (Noah Wiseman), emotionally stunted. One night before bed, Samuel presents his mother with a mysterious, rather frightening pop-up book to read, titled Mr. Babadook. Doing so doesn’t just leave Samuel sleepless with night terrors; it unleashes a sinister presence that forces Amelia and Samuel to confront their anguish.

This is the premise of writer-director Jennifer Kent’s stylish horror film The Babadook, shot by cinematographer Radek Ladczuk. Israeli director Tali Shalom-Ezer introduced Kent to the work of her friend Ladczuk while the two directors were in Amsterdam developing screenplays at the Binger Filmlab. Kent became fascinated with Ladczuk’s Suicide Room, and the two had a meeting via Skype. Soon after, the director of photography was in Australia for a week of pre-production meetings and, after a short break, six more weeks of prep.

Ladczuk, who studied at the famed National Film School in Lodz, Poland, became a cinematographer not through any sense of predestination — he just did it. “One day I passed the exam to film school, and this adventure started,” he says matter-of-factly from Poland, where he was shooting the feature Princess. “I don’t know why! I don’t have any family connection or tradition. I just followed my emotions. It is an amazing job.”

Kent gave Ladczuk a list of some 20 features to watch, including old movies from Georges Méliès’ body of work, German Expressionism films like Murnau’s Faust, and American horror films from the 1920s and ’30s. “She was inspired by old movies,” Ladczuk says. “She wanted to have all effects in camera and no CGI.” In fact,

Kent originally envisioned shooting The Babadook in black-and-white, but ultimately decided she wanted to create something different from the old, silent horror films. Instead, she went with a limited color palette — particularly in the house — of steel blue, burgundy and some teal. “We had an amazing Australian production designer in Alex Holmes,” says Ladczuk. “In this movie, Jennifer saw more of a psychological story than horror, though we added many horror elements in the design and camerawork. We understood that it was a mix of psychological drama and horror. It really is a story about a woman and her relationship with her son. Everything came from the mother’s perspective.”

The production was the first feature film to occupy the new Adelaide Studios sound stages in South Australia. The Babadook’s main set, comprising the interiors of Amelia’s Victorian-style house, was built on stage. With its muted hues, the house reflects Amelia’s mental state and, on a deeper level, serves as a metaphor for her mind. Initially slated to shoot the project over 30 days, the filmmakers realized that the number of in-camera special-effects shots caused too much of a crunch, so a few more days were added and paid for — along with elements of the design budget — by a small, online Kickstarter campaign. Ladczuk and camera assistant Maxx Corkindale also worked a few weekends with Kent to shoot some additional shots in the house for editing purposes. “It was low-budget for an Australian production,” the cinematographer says.

Ladczuk, who also served as the camera operator, shot with a base-model Arri Alexa with a set of Arri/Zeiss Master Prime lenses. He recorded HD 1920x1080 ProRes 4:2:2 HQ files to SxS cards.

Kent and Ladczuk were precise in devising the camera movements and composition. “We divided our movie into five chapters: anxiety, fear, terror, possession and courage,” he says. “Each had different elements of camerawork. At the beginning we had a very static camera where Amelia often was situated in the center of the frame. Usually, we shot her on a 32mm lens to be able to see her emotions. Then we added a handheld style to emphasize her emotions, and then Steadicam, which we called ‘floating camera.’ For the movie’s ending, we wanted to create very chaotic and uncoordinated movement, reflecting the Babadook’s point of view. We also used [increasingly] wider lenses for Amelia’s close-ups until finally, in one of the scenes, we were shooting her with a 14mm lens. Everything for us was motivated by the characters’ emotions.”

The Babadook opens with Amelia having a surreal dream that forces her to relive the car accident that took her husband’s life; after the dream, she falls back into bed. For the scene, a car partial and the camera were mounted on a rotisserie so the car and camera could rotate in tandem. The scene then cuts to the actor on a dolly being wheeled toward the bed, which was mounted vertically against a wall, for the in-camera falling effect.

Other in-camera effects are sprinkled throughout the film. “We had fast-motion and slow-motion effects, a lens out of the mount, a Lensbaby,” Ladczuk lists. “All scenes with the Babadook were stop-motion frame-by-frame. We had an animator, Michael Cusack, on set to help us with it.”

When the Babadook finally goes after Amelia, it crawls on the ceiling toward her on a set that was flipped, with the ceiling built on the floor. The nightmarish figure, played by Tim Purcell, moved step-by-step as Ladczuk shot five frames at a time. On the right-side-up version of the set, the Babadook was lowered incrementally toward the camera and shot stop-motion style. (The cables were removed in post.) “It was very tricky and uncomfortable for the actor,” Ladczuk notes.

Mr. Babadook, the pernicious tome that starts Amelia and her son spiraling, was also to be filmed as a stop-motion sequence. “That was the plan,” recalls Ladczuk. “The book was designed as a pop-up with elements that you could move. I had macro lenses for it. It was very complicated, and we didn’t have the time to do a real stop-motion animation — only a few hours — so it was shot in real time.”

Because black-and-white was not an option for the film, Kent had specific ideas for the lighting aesthetic to complement the desaturated colors. “She doesn’t like color in light,” Ladczuk says. “She wanted one color temperature. In my previous movies, I really liked to use gels on the lamps; to her, that is a modern light. I decided to create an old feeling through contrast and by the level of light rather than through color temperature. It was very strange for me, but I treated it as a challenge.”

Ladczuk focused on lighting the actors’ faces rather than keeping the backgrounds lit. The resulting look pulls and isolates the actors in the composition, particularly within the dark and dreary Victorian house. “I wanted the light to look natural at the beginning,” he explains. “The further we got in the plot, the harder and more surreal and expressive I wanted the light to be, because the light was motivated by fear. I avoided using light softeners so as to bring more expression to an actor’s face, especially in night scenes.”

In lighting the house interior, Ladczuk preferred HMI sources, such as Pars and Fresnels ranging from 200 watts up to a 12K, because of better color reproduction, though he had to make some exceptions. “Sometimes we didn’t have enough light sources to cover our set,” he says. “For example, Amelia’s bedroom was covered by HMI lighting, but the hall, living room, dining room and kitchen were covered with tungsten lighting for night scenes. I used windows as the main source of light, but for all night scenes I had two huge white sections of fabric for ceilings and used tungsten fixtures on dimmers to generate delicate, soft light from the top. I regulated the intensity depending on circumstances, used fill light from the floor and lit curtains from the outside.”

Ladczuk purposefully allowed the windows to blow out during day scenes because the production could not afford TransLites or backdrops.

Artfully contrasting with the cold Victorian interiors was the basement, where Amelia keeps her dead husband’s belongings — and her memories of him, as best she can manage — locked away. The basement was a real location as opposed to a constructed set, and although Ladczuk lit it in the same manner as the house interiors, warmer tones pervaded due to the influence of the red brick walls.

Other real locations included the nursing home where Amelia works. “We tried to reduce the color palette,” says Ladczuk, “but it was impossible to remove all of those elements and we ended up with pastel colors. Location always inspires, and that is why the light is different — softer and paler. We tried to add black elements in every frame just to create contrast. In the doctor’s office, we removed all [existing] elements and added some black lamps and a black table just to have contrast.

“Green also was not acceptable to Jennifer,” he adds. “For example, the scene in the city park [of Amelia and her sister on a bench] has a very strange camera angle. At eye level, we had a lot of green background, which she hated. Instead, the camera angle is really high. In the end, I grew to like it.”

Postproduction facility Kojo in Adelaide handled the color grading, with visual-effects supervisor and DI colorist Marty Pepper at the wheel. Originally, Ladczuk tried to link Kojo with post houses in Warsaw so that he could observe Pepper’s work onscreen. “After a few days of trying, I realized it wasn’t going to happen with the low-budget situation, so I just bought a ticket and flew to Adelaide,” he says. “For me, it is important to finish the movie with the colorist. The contrast and colors are very important to me, and also, this is my work.”

It turned out that the color-grading process was relatively quick. “I was surprised with how good the colors were in the rough cut,” the cinematographer says. “In the beginning, Marty fixed contrast and made one contrast layer, then focused on the alabaster skin tone for Amelia. At the end, he focused on colors like the greens and yellows, working with keys to fix our color palette and reduce unnecessary colors. After three days, he had those layers.

“I really like his style of work; it was a very good experience for me,” Ladczuk continues. “Before, I was more focused on finding proper style — focusing on one or two scenes instead of the movie as a whole. Marty’s work [takes into account] layers for the whole movie, and it’s a very fast style. After about five days, you can show the final product to a producer, and if you have more time, you can focus on details.”

With a slight re-size, The Babadook was mastered into a DCP format in 2K resolution.

“The level of professionalism on this movie was really high,” Ladczuk concludes, “and I was really lucky with the amazing Australian crew. For example, the key grip, Mike Smith, had everything on his truck. From a Polish perspective, that was something new for me!”

Tech Specs

- 2.40:1

- Digital Capture

- Arri Alexa

- Arri/Zeiss Master Prime