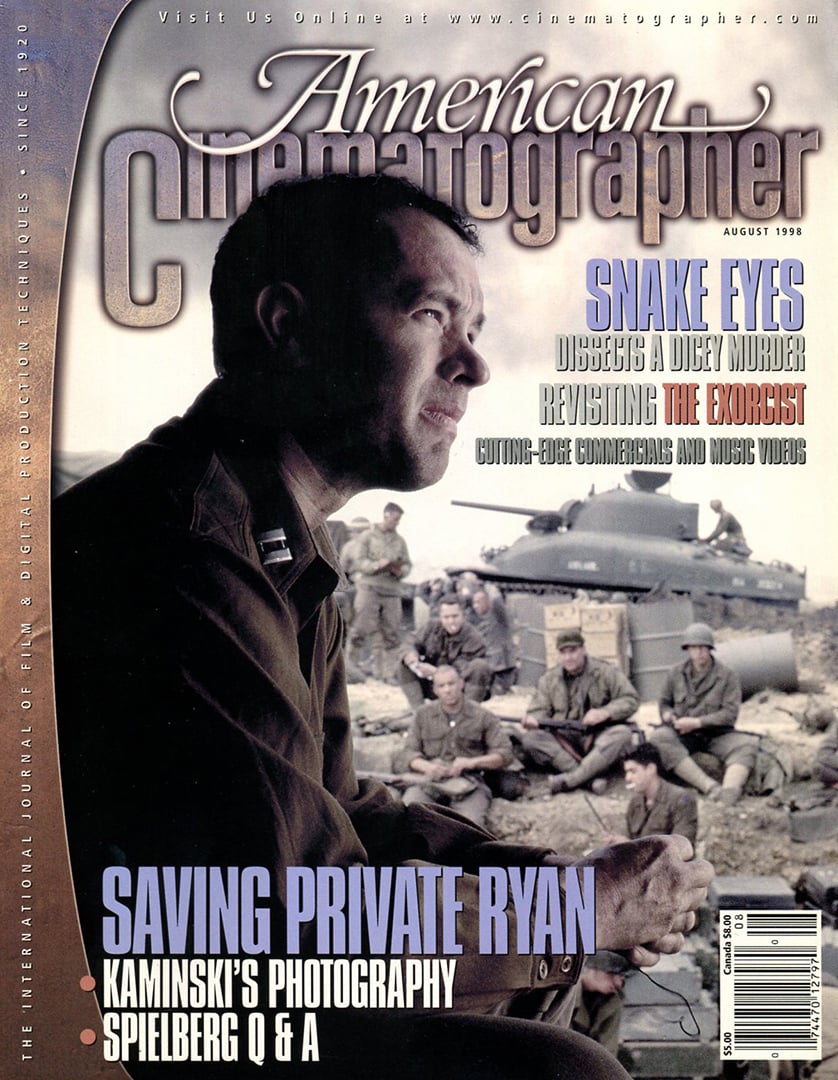

The Last Great War: Saving Private Ryan

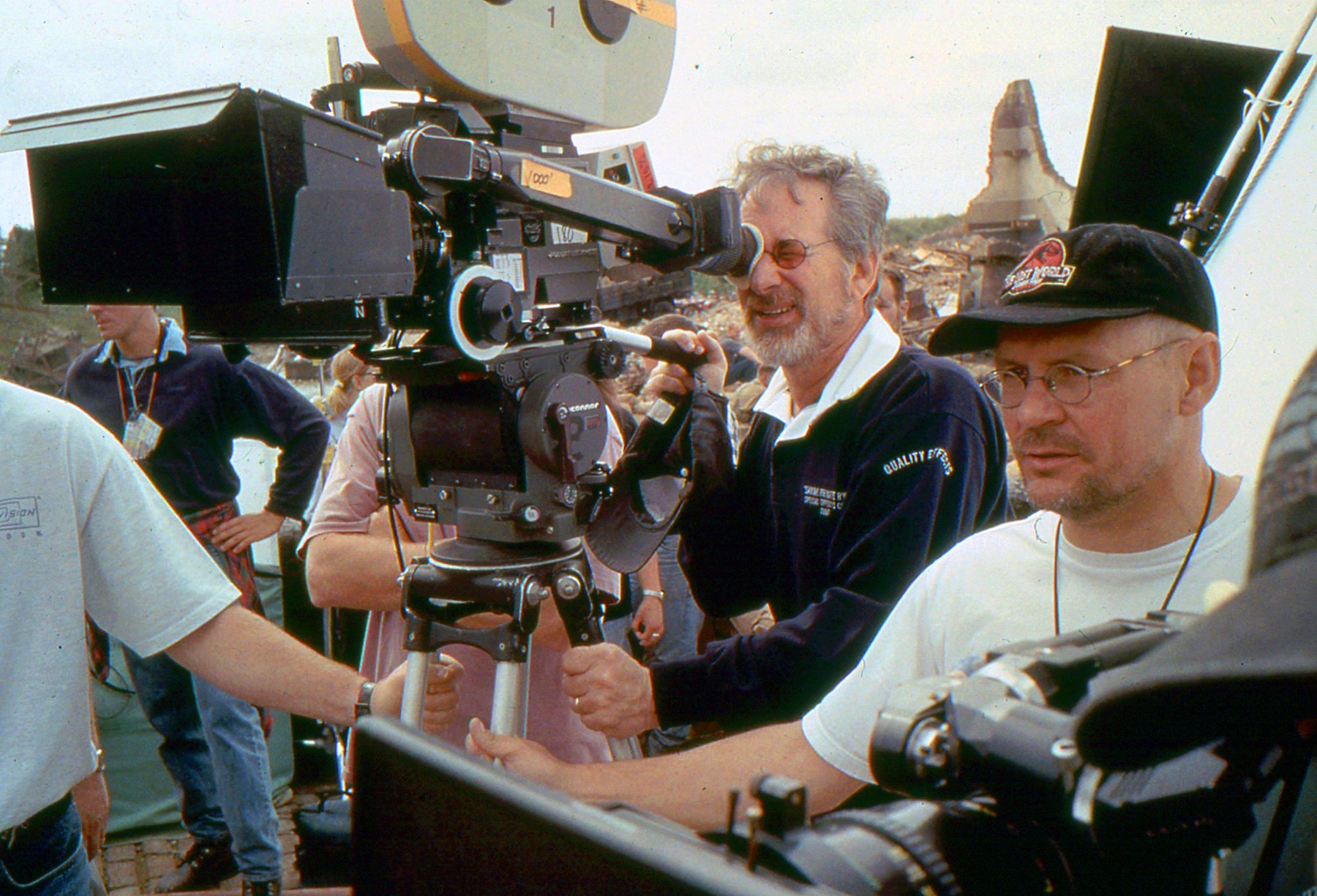

Cinematographer Janusz Kamiński and his crack camera team re-enlist with director Steven Spielberg.

Unit photography by David James

On June 6, 1944, approximately 2,500 American soldiers were killed while storming Omaha Beach on the Normandy Coast, as dug-in German defenders assailed the intrepid troops with a barrage of artillery fire from heavy fortifications. “Operation Overlord,” the invasion of Europe, had begun, and the bloody event known as D-Day proved to be the turning point of World War II, signaling the beginning of the end for Nazi Germany.

Director Steven Spielberg has revisited this narrative-rich era a number of times during his career, alternately exploring the dramatic, adventurous, tragic and even humorous aspects of the age. The filmmaker’s latest effort, Saving Private Ryan, teamed him for a fourth time with cinematographer Janusz Kamiński, who earned Academy, BAFTA and ASC Awards for the stark black-and-white photography he lent to Schindler's List (see AC Jan. ’94), Kamiński has since shot Spielberg’s subsequent films, The Lost World (AC June ’97) and Amistad (AC Jan. ’98). The latter earned the cameraman both Academy and ASC Award nominations.

Opening with the most graphic and elaborate film depiction of D-Day to date, the $65 million Private Ryan uses this monumental event as a springboard for its story. Loosely based upon actual WWII cases of families losing four or five sons in battle, the picture follows Captain John Miller (Tom Hanks) as he leads an eight-man squad behind enemy lines and into France to search for the last surviving Ryan brother (Matt Damon), whose three siblings have been reported killed in action. As a squad advances into greater and greater peril, its members — who include Sergeant Horvath (Tom Sizemore), Corporal Upham (Jeremy Davies) Medic Wade (Giovanni Ribisi) and Privates Reiben (Edward Burns), Caparzo (Vin Diesel), Mellish (Adam Goldberg) and Jackson (Barry Pepper) — begin to question the military’s decision to risk eight lives in the hope of saving just one.

Boot camp

After enlisting his principal cast members, Spielberg enrolled the actors in a grueling training course with military advisor and retired Marine Captain Dale Dye, who has lent his expertise to such diverse projects as Platoon, The Last of the Mohicans, Forrest Gump and Starship Troopers. For 10 full days, the group was subjected to a strict military regimen of pre-dawn reveille, five-mile runs, weapons training and military exercises, while getting no more than three hours of sleep a night under a soggy blanket. When their ordeal finally ended, the haggard-looking actors were primed and ready to simulate combat on film.

“We didn't have to shoot much in terms of makeup tests,” says Kamiński with a wry laugh. “After their experience in bootcamp, the actors were all pretty much beaten up. Saving Private Ryan was a physically demanding movie, because their backpacks were full and the guns were real and quite heavy. After two weeks of shooting, we didn't need any aging makeup — they all had dark circles under their eyes!”

Going to war

Saving Private Ryan’s intended pre-production period was severely truncated when Spielberg decided to shoot Amistad after completing The Lost World and before beginning work on the WWII epic. Nevertheless, Kaminski spent two weeks doing camera tests in Los Angeles prior to leaving for England, where most of Ryan would be shot.

Kamiński notes that it's during these tests that he determines the look of a film. “When I read a script and like the story, I respond to it on an emotional level,” says the cinematographer. “I have a concept of who the actors are and where the story is taking us, and I then imagine how I can enhance the storytelling through visuals. The story automatically dictates how I'm going to light it. That may sound simple, but it's not, because it's my personal interpretation of a script that allows me to create the visuals. That interpretation is based on my own life experiences, aesthetics, education and knowledge, all of which help to shape my understanding of a story.

“In a funny way, I previsualize my work by cancellation. For instance, I may cancel out other movies that I don't want a particular picture to look like. I may not have known exactly how I wanted Saving Private Ryan to look, but I knew I didn't want it to look like The Lost World, which had hard light and contrast. By eliminating certain visual styles, I narrow down the concept for the film I'm working on. And then I do a lot of research, looking through books and paintings and watching other movies. I think of certain color schemes, compositions and camera moves that I'd like to use in the film, and all those choices result from what the written material dictates.

“Later on in prep, I start doing tests to figure out how to achieve the appropriate visual style by applying various camera techniques. For example, even though Private Ryan is not necessarily a true story, it's set in a very realistic scenario. We're all familiar with World War II and the invasion of Normandy, so there were certain historical realities that I had to fulfill. And obviously, a lot of our knowledge of that war comes from footage shot by the combat photographers or from very masterfully staged films, such as the Nazi propaganda films of Leni Riefenstahl.”

Spielberg and Kamiński initially considered rendering Private Ryan monochromatically, as they had previously done on Schindler's List. “Black-and-white was the right choice for that film because of the subject matter and because most of the real footage of Nazi atrocities was photographed in black-and-white,” relates Kamiński. “However, there is a tremendous amount of documentary footage from World War II that was photographed in color. In fact, [renowned director] George Stevens was a combat cameraman and shot a great deal of footage in color. Steven and I really didn't want to shoot Private Ryan in black-and-white, and I think it would have been a little pretentious to do another World War II film that way.

“We also wanted to shoot this picture in color because there is some blood in the film and we wanted to play with the reds, even though we did desaturate the colors through the use of ENR,” Kamiński expands, noting that the use of the special Technicolor process was a key reason to do extensive camera tests. “I knew the movie would have more of a bluish tone to it, and with 70 percent ENR, the color of the blood on the uniforms and the ground was a primary concern. For scenes in which the characters got wounded, we wanted to know how the blood would look on the uniforms and how it would look after they wore those uniforms for a couple of days. Because we were dealing with a World War II drama, the wardrobe was already muted, and since we were shooting in England and Ireland, we had day after day of foggy, rainy climate, which automatically made the light more diffused and the colors more pastel. We therefore compared various levels of ENR, and based on those tests, the special effects department mixed a certain amount of blue into the blood to make it a bit darker than they normally use.

“I think the biggest misconception about ENR that everyone talks about is what the process does to the shadows to make them deeper and richer,” he adds. “Yes, that is one aspect of the process, but the biggest thing about ENR that no one seems to be talking about is what it does to the highlights and colors. If you shoot a test and compare a shot with ENR and without, the clothing will look much sharper and you will see the texture and pattern of the fabric in the ENR print. This was especially true on Amistad, on which we used about 40 to 50 percent ENR. As a result, all of the Africans’ clothing had much more texture. On Saving Private Ryan, the uniforms benefited as well. The edges of the shirts and the helmets were sharper, and the process also worked magic on metallic surfaces and water reflections, which become like mercury. It's so gorgeous.”

After arriving in England, Kamiński conducted another week of tests to further pinpoint his visual approach. “[Famed Life magazine photographer] Robert Capa's war photography was one of the guiding references for the film,” he explains, “but Steven and I didn't talk much about how we were going to do the movie during prep. I prefer to shoot tests that show him what I intend to do photographically. By that point, I already made certain selections and decisions about a possible visual style, so I wanted to give him a range of different ideas and techniques to get him excited and inspired. In Private Ryan, I wanted to take a major Hollywood production and make it look like it was shot on 16mm by a bunch of combat cameramen. That was a conscious decision, but thankfully Steven is a very visually oriented director and is willing to take certain chances. However, he also has a sense of what is too far!”

Battle plans

Saving Private Ryan begins with a truly harrowing 25-minute depiction of the carnage and chaos experienced by the soldiers storming Omaha Beach. Both Spielberg and Kamiński sought to infuse the sequence with a high degree of realism, and studied newsreels and documentaries shot by combat cameramen in order to capture a true sense of the insanity and frenetic panic of war. “We wanted to create the illusion that there were several combat cameramen landing with the troops at Normandy,” the cinematographer submits. “I think we succeeded in emulating the look of that footage for the invasion scenes, which we achieved with both in-camera tricks and other technological means. First off, I thought about the lenses they had back in the 1940s. Obviously, those lenses were inferior compared to what we have today, so I had Panavision strip the protective coatings off a set of older Ultraspeeds. Interestingly, when we analyzed the lenses, the focus and sharpness didn't change very much, though there was some deterioration; what really changed was the contrast and color rendering. The contrast became much flatter. Without the coatings, the light enters the lens and then bounces all around, so the image becomes kind of foggy but still sharp. Also, it's much easier to get flares, which automatically diffuses the light and the colors to a degree and lends a little haze to the image.

“If I had two cameras running on a scene, I'd mismatch the lenses on purpose, using one with coated Ultraspeeds and one without coatings. That gave us a certain lack of continuity in picture quality, which suggested the feeling of things being disjointed.

“Next, we shot a lot of the film with the camera shutter set at 45 or 90 degrees. The 45-degree shutter was especially effective while filming explosions. When the sand is blasted into the air, you can see every particle, almost every grain, coming down. That idea was born out of our tests, and it created a definite sense of reality and urgency.”

Spielberg additionally wanted the camera itself to feel the impact of the explosions. Key grip Jim Kwiatkowski reports, “During the tests on the backlot at Universal, Steven was talking about this one shot in Empire of the Sun in which he shook the camera to get the effect he wanted. With that in mind, the best boy, Bob Anderson, attached an electric drill to the pan handle of a fluid head and locked an oblong bolt with an eccentric washer in the chuck. When activated, it created a wobbling movement and the camera shake we wanted.”

“It's a great effect,” attests Kamiński, “but you certainly can't handhold the camera with a drill attached to it. Plus, your eye is constantly bopping against the viewfinder. So for handheld work, we used Clairmont Camera’s Image Shaker, which is an ingenious device. You can dial in the degree of vibration you want with vertical and horizontal settings, and mount it to a handheld camera, a crane, whatever. It's heavy, but my camera operator, Mitch Dubin, did some amazing handheld work with it. At first we used it very conservatively, like when there was an explosion or a tank rolling by, but after seeing dailies, we just dialed it in and out as Mitch ran with the camera.

“I also used another technique that Doug Milsome [ASC, BSC] utilized on Full Metal Jacket [see AC Sept. 1987] where you throw the camera’s shutter out of sync to create a streaking effect from the top to the bottom of the frame. It’s a very interesting effect, but it’s also scary because there’s no way back [once you shoot with it]. It looked great when there were highlights on the soldier’s helmets or epaulets because they streaked just a little bit. The amount of streaking depended on the lighting contrast. If it was really sunny, for instance, the streaking became too much. However, if it was overcast with some little highlights, it looked really beautiful. The streaking also looks fantastic with fire, and that’s what Milsome primarily used it for in Full Metal Jacket.”

Kamiński employed Panavision Platinum and Panastar camera throughout the Private Ryan shoot, and had Samuelson Film Services in London prepare one unit with a purposely mistimed shutter in order to create the described streaking effect. Used in combination with a narrow shutter, however, the effect was negated as the shortened shutter interval fell within the moment that the film was in its stationary position. Due to this anomaly, however, the “streaking” camera could also be used for normal shooting provided that the shutter was set between 45 and 90 degrees.

Storming the beach

With a visual approach locked in, the Private Ryan production was fully geared up for battle. While scouting the actual Omaha Beach in France, which is now a historical landmark, the filmmakers found the area to be too developed to suit their needs. The company then found a stretch of coastline in Ireland that featured an uncanny similarity to Normandy’s gold-sanded beaches and sheer cliffs. Production designer Tom Sanders transformed the Irish coast into a war-torn battleground by strategically dressing the landscape with Teller mines, iron hedgehogs and barbed wire, as well as concrete pillboxes and bunkers.

Kamiński shot Private Ryan in the 1.85:1 format entirely with Eastman Kodak EXR 5293 stock, which he pushed one stop to a 400 ASA rating. He also utilized a ½ Coral filter in place of normal 85 correction to lend a slight bluish tint to the imagery. “Pushing the film shifts the contrast and makes it easier to burn the highlights out,” the cinematographer explains, “but you also get a bit more detail in the shadows. Occasionally, I pushed the film two stops to 800 ASA and it was still fine. I’d take 93 pushed two stops over using Vision 500T pushed one stop.

“Additionally, I again used a Panaflasher in conjunction with the ENR process, as I had on Amistad. Because of the contrast that you get with the ENR, I was flashing at about 15 percent so that I didn’t get totally sharp blacks. I was looking for a slightly flatter look. The Panaflasher also contributed greatly to the color being more desaturated. You gain the contrast back with the ENR, but you’ve desaturated the color already with the Panaflasher.”

In re-creating the infamous D-Day invasion, the production located many of the original “Higgins boats” landing craft — in Palm Springs, California — that were used in the real-life 1944 assault. The film company also employed 750 extras provided by the Irish Army, who were then dressed in uniforms painstakingly re-created by costume designer Joanna Johnston and equipped by armorer Simon Atherton with authentic period weaponry. The beach was intricately rigged with squibs and mortars by special effects supervisor Neil Corbould, while the “war” itself was meticulously planned and rehearsed by stunt coordinator Simon Crane.

“We started Saving Private Ryan with the invasion scenes, which we shot for three weeks,” recounts Kamiński. “The physical and technical challenges of just getting the shots were daunting. Steven wanted to block huge day exterior scenes with hundreds of extras and do them in just one or two takes with two or three cameras. But there was a reason for that as well. It you have a huge field that takes a day and a half to pre-rig with squibs and explosives, you only have one take!

“Amazingly, Steven would often just cover a scene with one continuous shot. There were a couple in which blood or water splattered on the lens, but we kept shooting because that’s what I assumed would happen in reality. Combat cameramen would not have time to clean the lens. They’d just have to keep on going. What we got really had a documentary feel to it.

“We shot handheld for probably about 90 percent of Saving Private Ryan,” Kamiński notes, “whereas on Schindler's List, we handheld the camera about 60 percent of the time. Shooting that way was very demanding on the operator, Mitch Dubin, as well as B-camera/Steadicam operator Chris Haarhoff, because most of the handheld work was done from almost ground-level, not from the shoulder. When the soldiers were running, they were really running low. We wanted to be very close to them, so Mitch and Chris would often have to operate while looking at a little monitor as they ran. Those shots were also difficult because the camera had to be covered to protect it from all the sand and explosions, not to mention that everyone's movement had to be choreographed because we were running across fields covered with live squibs and mortars.” The cinematographer adds that he was aided by A-camera first A. C. Steve Meizler and B-camera first A.C. Kenny Groom, as well as second A.C.s Tom Jordan and Robert Palmer, and loader Roslyn Ellis. Additional action was covered by C-camera operator Seamus Corcoran.

“Janusz and Steven wanted the camera to be a real participant in the film,” Dubin details. “The soldiers jump out of the landing boats but are trapped in the surf by bullets from the German emplacements on top of the cliffs. At a certain point they make this mad dash to the edge of the cliff, which they called the ‘shingle.’ That was a very involved shot with all of the actors, hundreds of extras and a huge number of effects. We had three separate cameras rolling; I was following Tom Hanks as he ran. When we rolled the cameras and Steven called action, all hell broke loose. I just remember running for my life and following Tom. When we hit the shingle, we both looked up at each other, astonished that we had actually run through this event. We did it in one take and then moved on. That shot really set the tone for the rest of the film.”

Adding to Dubin’s task was the weight of the Platinum camera (about 34 pounds with 500’ mag and lens) when coupled with the Image Shaker (about 15 pounds) and Panaflasher (about 4 pounds). The extensive use of low-perspective, handheld work prompted the camera department to call in a lighter unit. “We got a Moviecam SL, which worked out great,” recalls Dubin. “It’s one thing to carry a camera on your shoulder, but everything in this film was down low, which is very difficult, especially when you’re running with the camera almost touching the ground.

“In Steven’s movies, the camera is always an active participant in the storytelling process,” Dubin continues. “Along with the primary concerns of the script and the acting, he tells the story through the framing. Accordingly, the frame and image are of utmost importance. When you add the handheld camera into the mix — which is a very immediate and responsive form of operating — the whole process becomes even more exciting.”

Though he strove to simulate the battle’s graphic scenes of carnage as realistically as possible, Kamiński didn’t lose sight of the real importance of the story. “The film is realistic because of the actors’ performances,” he opines. “Audiences will be shocked by what they see during the invasion sequences, but the most emotional moments are when the characters look at each other afterward and have a chance to reflect on what they’ve just experienced. There’s a little push-in shot on Tom Hanks after they’ve conquered the beach — which we’ve just witnessed firsthand — and his reaction is such a powerful moment that the audience will just lose it emotionally. It’s this human element that makes the film so powerful. We are all familiar with gore, but the way that it is presented in this film is similar to how it was done in Schindler’s List — bang and you’re dead.”

Lighting D-Day

Fortunately for Saving Private Ryan’s crew, the production was blessed with fairly consistent overcast skies throughout the three-week D-Day shoot, which closely resembled the actual weather conditions on that fateful day in 1944. Kamiński took this into account while devising his approach to not only the Omaha Beach sequence, but the entire film’s photographic design.

“For the most part, we really didn’t light much on the invasion,” explains gaffer David Devlin. “When the actors were in the Higgins boats, we did add some light with white and silver bounce cards to up-light the actors a little so we could see their eyes under their helmets. The ‘lighting’ was more about how the negative was being exposed, the lenses and the use of the ENR. The great thing about war movies is that almost everything is drab, dark and dirty, so we weren’t fighting those elements. In fact, the actors’ eyes become [comparatively] bright because their faces are so dark and dirtied.”

Kamiński determined that with constant overcast light, he could suitably control the film’s look with the aid of the Panaflasher and the ENR process. Additionally, he incorporated the heavy use of smoke — which obviously was a key component in selling the “war” visually — as an essential ingredient in his photography. Dense black smoke also offered the added benefit of blocking out any unwanted sunlight that might have sneaked through the cloud cover. Devlin recalls, “One of the most amazing and awful things I’ve ever seen were three big drums of diesel fuel that the special effects guys were burning to create huge clouds of black smoke. They also designed a system for making white smoke that was mounted in the bed of a pickup, which was attached to a trailer with a 200-gallon tank of diesel fuel. They had about six of these pickup trucks that could drive up and down the beach as a self-contained unit. The lighting for that whole sequence was more about taking the light away, and when they turned those smoke machines on, it would cut down three or four stops of exposure.”

“For closer shots, we’d sometimes bring in a bounce card or solid for negative fill,” adds Kwiatkowski. “One of the things I’ve learned over the years while working outside is that if the cinematographer wants to control the sunlight — and the production can afford it — you should have a crane and a large frame standing by. That way you can cover a large area and get the lines [of the overhead’s coverage] out of the shot. Because we used a 30’ by 30’ silk and smoke on Private Ryan, the smoke would cover any of the lines made by the silk. Between those two elements, the ‘lighting’ was consistent and it worked great.”

The search

Following the frenetic chaos of the D-Day sequence, the film takes a breather to develop the characters and establish the squad’s mission to find Private Ryan. Kamiński explains, “During the scenes where the characters are not in combat, the camera is more at rest and on a dolly more often. We sometimes used a special ‘switcher track’ designed by Jim Kwiatkowski, which allowed us to dolly in one direction and then come to a junction and dolly 90 degrees in another direction. We also paid more attention to the lighting in those sequences. I wouldn’t introduce sunlight into a scene that was overcast, but with the ENR process, we had to light the actors because the image could get too contrasty, especially under the helmets, and we would start losing their faces. Sometimes we’d just fill them in with showcards, or sometimes we’d use 12K or 18K HMIs bounced from Griffolyns set faw away.”

Devlin recalls, “There’s a scene in which Tom Hanks and Tom Sizemore are driving in a jeep and talking. I was busy lighting the jeep. It was a simple setup using a 4K Par through two layers of diffusion to provide an overall base to fill in their eyes as they rode in a jeep, which was on a Shotmaker-type camera car. I really didn’t think about what was going to be in the background. When we finally went to shoot that shot, however, I realized that there were literally hundreds of the Irish Army extras marching in the backgrounds while the scene went on for something like four minutes. The power of having all of these men and machinery in the background as they drove along was really incredible.”

Kamiński was also able to modify the sunlight to his liking for some shots by utilizing Rosco #3004 Half Soft Frost Diffusion in place of an overhead silk. “For some of the exteriors, we chose to use Half Soft because it allows the light to have some direction while still softening it,” Devlin explains. “Whereas with a silk, you create an overall soft ambiance, but you then have to compete with the much-brighter backgrounds. A lot of times there’s really no difference between having a silk or a solid up. One nice thing about Half Soft Frost is that it allows the sun to have a strong direction, and yet the light will wrap enough to fill people’s eyes.”

As the soldiers continue their quest for Private Ryan, they take shelter for the night in a bombed-out church. Illuminated by candlelight, the “soldiers are sitting analyzing what has happened and what is ahead of them,” Kamiński notes. “It’s a very beautiful, underlit scene — about three stops underexposed — that has a painterly feel, as if it was lit only by candles. There’s a very nice section of dialogue between Tom Sizemore and Tom Hanks. I wanted to create the sense that the light was coming from the candles below them, but I didn’t want to get big shadows. I ended up lighting them with China balls fitted with ½ CTO and ½ CTS. I then used a flag just outside of frame to take a little of that soft light off Sizemore, so his face was a little brighter on the bottom and then dropped off. I don’t like candle flicker effects very much, so the key was a normal [non-flickering] light, but I did have a little flicker on the fill to give it some movement.

“I’d tested China balls in the past and never liked their effect, but I’m learning more about how to use them now. The key is to underexpose by 1 ½ stops. You also have to keep them just outside of frame but away from the walls, so you get that nice falloff in the light. Philippe Rousselot [AFC] has been using them for years, but if you look at his films, you’ll notice that the people are always positioned away from any walls. He may have a very soft China ball a few feet away from the actors, but everything falls dark behind them. Because they are no other light references in the frame, their faces still glow ever if the shot is 1 ½ to 2 ½ stops underexposed.”

Home of the brave

Although shot entirely in England and Ireland, there are a few scenes in Saving Private Ryan that ostensibly take place in the United States. The first occurs just after the D-Day invasion, and establishes the premise that three of Private Ryan’s brothers have been killed in the war. “There’s a scene in which we see this huge room filled with secretaries writing death notices to the families of all of the deceased soldiers,” reveals Kamiński. “We shot that in an existing location in England that used to be an airplane manufacturing facility. For all of the scenes set in America, I wanted to introduce a bit more color and create more of a sense of sunlight as a relief from the muted tones of the rest of the film. I therefore had 18Ks pumping in the windows.”

“For the scene in question, we had eighteen 18Ks outside this band of windows that were mounted on a construction trussing and fitted with ½ CTO and CTS,” expands Devlin. “A problem that I’m sure everyone has struggled with is that even though you may put an 18K outside a window, it’s never bright enough; the background still blows out. In this circumstance, we didn’t want to deal with that. It was a big shot, so it meant a lot for us to nail it. At first, we wanted to put dichroic Dino lights up to create this big wash of light so the audience would really feel the heat of the sun. But because they really don’t use dichroic Dinos in England, we ended up using the 18Ks, which I put as close together as possible. Since there were so many of them, we really didn’t see multiple shadows.

“Because the windows’ mullions were made of 8'-wide I-beams, we certainly couldn’t hide light behind them. If we’d put up only two or three 18Ks, we’d have wound up fighting the mullions creating criss-cross shadows, which would have forced us to put up flags. But once you start putting up flags, the light becomes defined and it no longer looks like one source anymore; it’s just terrible! But [using an array of] 18Ks worked out quite well. It was kind of like having our own sun. We could say, ‘We want the sun to be three stops over,’ and we didn’t have to fight to control the ambiance in order to expose it.”

Once more unto the breach

Considering the intensity of the picture’s opening sequence, the filmmakers felt that Saving Private Ryan’s ending needed a final skirmish with the Germans in order to balance the film’s dramatic weight. This climactic sequence was set in the fictitious French village of Ramelle. Production designer Tom Sanders built the decimated town in Hatfield, Hertforshire — approximately 45 minutes north of London — at the abandoned British Aerospace facility which served as the production’s backlot and English base camp.

“The set Tom Sanders built was amazing,” recounts Kamiński. “It was three blocks long and amazingly detailed. As a cinematographer, you have to keep your eye on the smallest details in art direction; when you’re working on such a large-scale film, only you have an idea of what’s going to appear on the negative. Private Ryan is so authentic that the smallest details that one could normally get away with wouldn’t work here. If a group of soldiers are sneaking against a wall and that wall doesn’t look absolutely real, you’re ruining the scene, no matter how good the scene may be.”

Devlin offers, “Tom Sanders did a great job with the coloring and in making the buildings distressed and dark, but the one thing that really made the look of the movie was working with the standby painter, Joe Monks. When we started working in Ramelle, if we felt a building was too bright, and that bringing in flags and cutters for a simple day exterior shot would involve too much work, we’d have Joe come in and make the building darker. We’d give him a 10' by 40' wall and in five to 10 minutes he’d be done. That gave the sets much more depth and separation.”

Kamiński found that he used much more lighting in the village than he could in the open fields of Normandy simply because there was the opportunity to hide the fixtures and illuminate the interiors of the buildings. The village set was pre-rigged with cables in conduits that ran under the entire town. Rubble was then piled on top of the pipes to hide the distribution boxes. “There’s a shot where Jeremy Davies runs into a building and sees through a window to one side that the Germans are approaching,” submits Devlin. “It was very dark inside the building [compared to the outside], so in order to maintain a certain amount of ambiance and the feeling of light coming in through the window, we used 18Ks with Half Soft Frost to blast through the windows.”

“That was a great shot,” agrees Dubin, who describes how he operated the scene: “We started on the bombed-out street as these German tanks approach. The tank shoots, blows up an emplacement, and the whole frame fills with smoke. Then Jeremy comes running out of the smoke and we follow him across the street as he runs into a burned-out cafe. We run up some stairs after him to the second floor and see out the window that another German tank is advancing and firing toward us. Jeremy runs across the room to another window and we follow him. But as he stops at the window, the camera continues moving, going outside the window to show the view down the street, raking the building. Dolly grip John Flemming and his crew built a platform so that I could walk right out the window and see down the street. I really had to have faith in John, since I was blindly walking out the window and had to be perfectly positioned on that platform!”

War and remembrance

Kamiński and his crewmembers all feel that Saving Private Ryan was truly a once-in-a-lifetime experience. And though the lighting approach was somewhat simplistic, the resulting imagery is breathtaking. “You don’t always have to provide beautiful lighting,” submits the cinematographer. “I often think ugly lighting and ugly composition tells the story much better than the perfect light. Sometimes a brightly front-lit image may be much more powerful than a silhouette. It all depends on the story. You can’t really preconceive certain visual metaphors, because then the symbol really isn’t a symbol anymore — it’s more of a gimmick. What’s great about cinematography is that you work from your instincts and people later see your work and come up with [an analysis] that you didn’t even realize, but which may make perfect sense.

“I’m learning more and more about lighting,” he concludes. “But you have to be encouraged by the directors. They allow you to make the choices that take the movies to a different level. Directors can allow cinematographers to advance to another level because we all have that capability in us. Some are so scared of taking risks that they won’t allow their cinematographers to try something new. But you can create such powerful and meaningful images by taking chances. I’m talking about things like what Robbie Müller [BVK, NSC] did on Breaking the Waves. Bob Richardson [ASC], Vittorio Storaro [ASC, AIC] and Malik Sayeed are also very experimental. Newton Thomas Sigel [ASC] did some great work on Fallen. And what Harris Savides [ASC] did on The Game was fantastic; I can’t wait to see what he did for [actor/director John Turturro’s upcoming film] Illuminata.

“We’ve all got the ability to do groundbreaking work, and nothing is stopping us from using very experimental techniques in a major Hollywood movie if the subject matter allows it and the director is willing to go there.”

You can listen to a Saving Private Ryan 20th anniversary AC Podcast interview with Kamiński here.

Saving Private Ryan was selected as one of the ASC 100 Milestone Films in Cinematography of the 20th Century.

Author Christopher Probst became a member of the ASC in 2018.

If you enjoy archival and retrospective articles on classic and influential films, you'll find more AC historical coverage here.