Shadows and Shivers for Blood Simple

The film’s director of photography details his journey with the Coen Brothers to create the low-budget neo-noir Texas thriller.

This article originally appeared in AC, July 1985.

There is almost no problem in the making of a feature film that cannot be solved by throwing money at it. More lights, more time, more crew, a bigger crane, a re-shoot, can all be bought with a big-time budget.

One of the challenges of shooting Blood Simple, a Texas murder mystery shot in Austin, Texas, was to make a $1.5 million movie look like 10 times that. The money was raised over a period of almost a year in the form of a limited partnership. The director, Joel Coen, had never directed before; his younger brother, Ethan, had never produced a film (and worked as a statistical typist at Macy’s to pay their rent while they raised the money).

I had never looked through a 35mm camera.

The money was raised by shooting a three-minute trailer of the movie [starring Bruce Campbell], as if it was finished and about to appear in your neighborhood theater. The trailer was our selling tool. It showed prospective investors that we could make something that looked like a real film, and it was something to invest in that had a recognizable form, unlike a treatment or script, for which none of the investors had any expertise. We were so low-budget that we waited until “President’s Weekend,” to shoot the trailer, when we could rent the 35mm camera over Washington and Lincoln’s birthdays, using the camera and lights from Thursday until Tuesday and paying a one-day rental charge (thank you, FERCO). I taught my cousin, Kenny, a neuro-pharmacologist, how to pull focus.

“For Blood Simple, the lighting was used as a psychological tool. For the film to be effective, the film had to be dark and contrasty.”

— cinematographer Barry Sonnenfeld

Eight months after we shot the trailer, we had our money and were on our way to Austin to make our movie. Blood Simple is a tightly plotted murder mystery in the film noir tradition. The plot involves the owner of a bar who discovers that his wife is having an affair with one of his bartenders. He hires a sleazy “good ol’ boy” detective to kill his wife and bartender. The detective has a better idea. He takes a photograph of the lovers in bed, and doctors the snapshot to look like they have been shot to death. The detective presents this photo as proof of a job well done, gets paid by the husband, and then shoots him. In effect, the detective has committed the safer murder. He leaves the wife’s gun, which he has stolen from her pocketbook as evidence for the police, when, he assumes, the body is discovered.

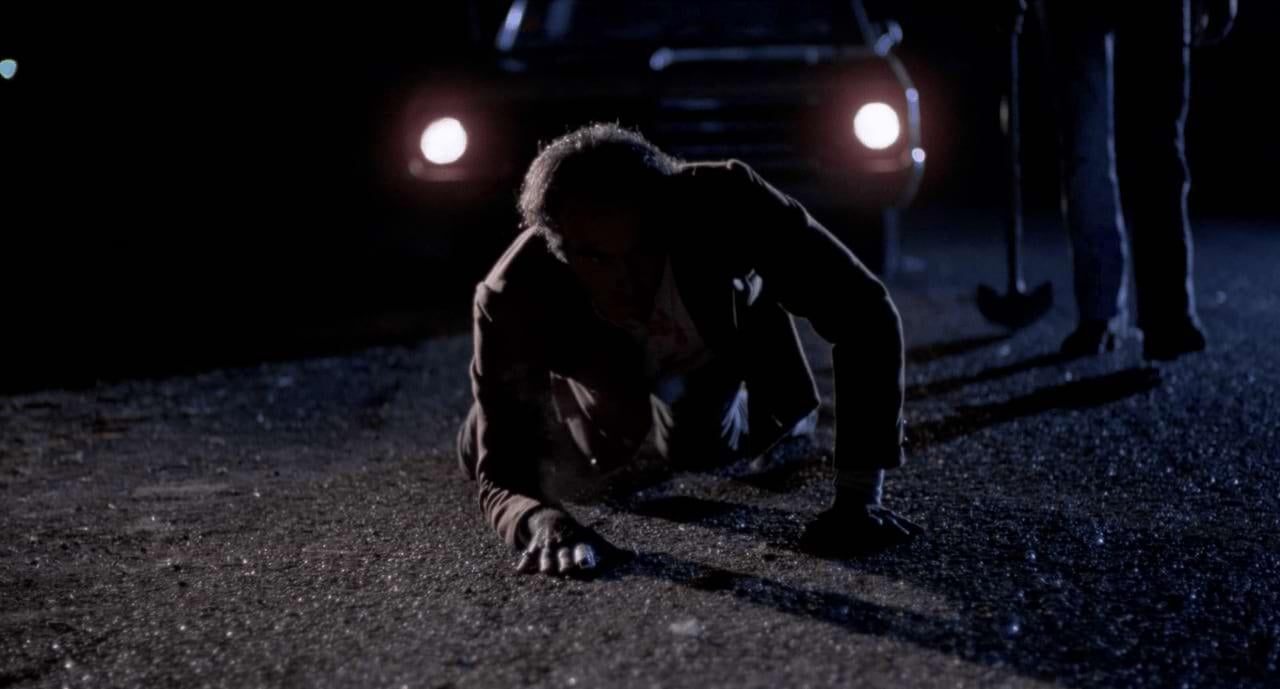

Unfortunately for everybody concerned, the lover comes to the bar that night, finds the body and the gun, and assumes that the wife committed the murder. He cleans up the mess and goes to bury the body in a field. However, he discovers that the body isn’t quite dead and is forced to finish the job himself. He then goes back to the wife and says, “Don’t worry, I took care of everything.” She doesn’t know what he’s talking about, and their misunderstanding leads to mistrust, and several more murders.

Every scene in Blood Simple was storyboarded. The only effective way to bring a low-budget film in on budget is to pre-plan everything. Pre-production is cheap compared to standing around the set with a crew, scratching your head, saying things like, “What would it look like if we put the camera over here?” The other reason, besides economics, that the film was storyboarded was the intricate nature of the plot. Certain visual elements repeat themselves in ironic visual ways, and these were all planned. Visual devices such as match cuts, sound overlaps, and camera-locked-down dissolves are all cheap and easy to do if they are thought about ahead of time, and tend to give a film a production value far beyond the cost of achieving these effects. There is a stretch of 20 minutes in the film with no dialogue which works totally on a visual/filmic level.

We were very lucky to have Tom Prophet as our key grip. Tom’s wife felt that Los Angeles was no longer geologically sound, and convinced Tom to get out of L.A. while they could still drive out. They relocated in Austin, luckily for us. Tom taught us a lot of Hollywood high technology with his pipe dolly and other rigging devices, and we taught him some low technology as well. Joel and I decided early on that we wanted to move the camera a lot, and when the camera wasn’t moving, we sometimes would dolly or raise or lower lights during the shot, so there was always some kind of apparent movement.

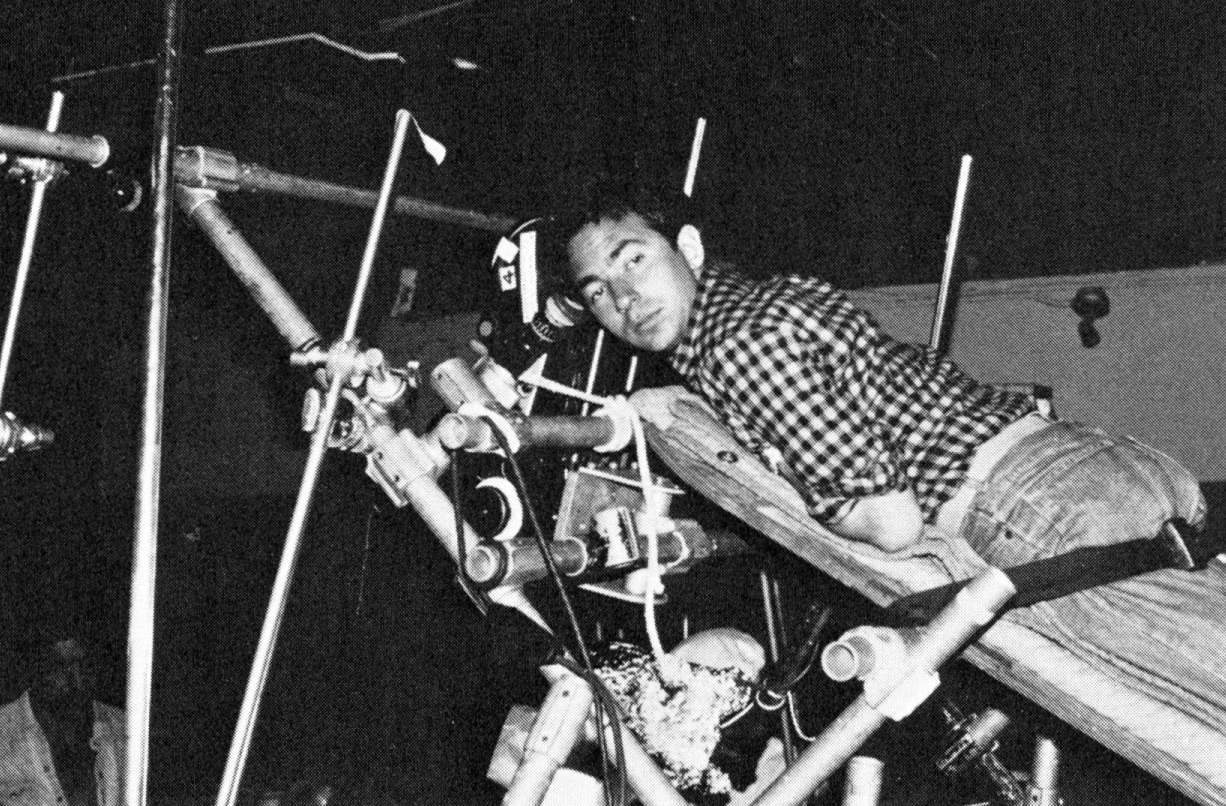

One of the cheap but efficient ways we moved the camera on Blood Simple was by dragging me around the floor hand holding an Arri BL3 while lying down on a sound blanket. This was quite effective since not only could we virtually be on the floor with the camera, the grips could actually pick up the blanket during our moving shots and turn the sound blanket into a crane. Another device we used to move the camera I believe was first used by Caleb Deschanel [ASC] on More American Graffiti, and was shown to us by Sam Raimi, who directed Evil Dead.

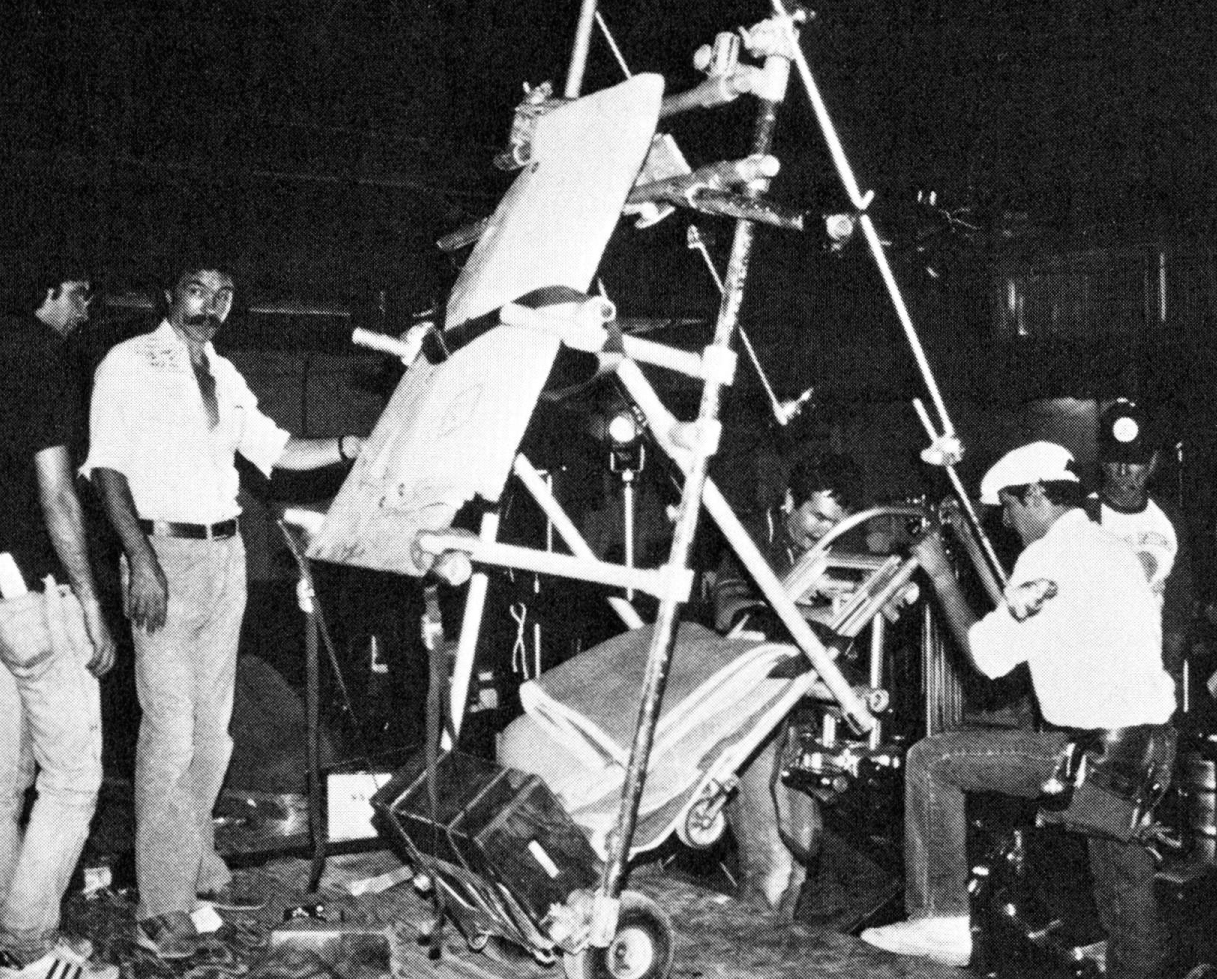

This device is the “shaky cam,” and cannot be beat at any price. The ‘shaky cam’ is a two-inch by 12-foot piece of lumber with a handle at either end of its 12-foot length. The camera is then centered on the board. An Arri-2C with a Kinoptik 9.8mm lens was used. With a grip at either end, the camera was raced along the ground at full speed, approaching the fighting wife and husband. Due to the extreme wide-angle lens, in a matter of a couple of seconds, the camera races from an extreme wide shot into a super close-up of the wife as she bends back and breaks her husband’s finger. In effect, all the shaking of two grips, racing at top speed along rough terrain, are smoothed out by the time the shakes reach the middle of the twelve foot shaky cam, and the camera seems to float. It was a very enjoyable shot to watch being made, since it looks like such a stupid idea. I would run behind the camera, not looking through the viewfinder, but still getting a sense of level and angle. I also got to yell “Duck!” at the actors, since as the shaky cam raced towards them, it was also rising from several inches off the ground to eye level, and the device has the stopping ability of a Boeing 747.

Another unusual and effective device we used was to lock the actress and camera to each other. For this, we used Tom’s speed rail. The actress was strapped down into what looked like a torture device. The camera and I were then strapped in four feet in front of her, and the whole device was rigged with a block and tackle to a beam in our studio. We then had two backdrops built. The backdrop directly behind her, at the head of the shot, was of the back room of the bar. On the floor, we built a bed. As the contraption pivots 90 degrees on itself, the actress, in effect, leaves one scene and falls through space past a series of side lit inkies, and eventually lands on her bed, and a different location in the film. Not only is this an effective transition visually, but psychologically as well, since, at this point in the film, she’s quite confused. Since the actress and camera are stationary to each other, there is almost a feeling of the two scenes floating towards her.

Originally, my thought for the lighting on Blood Simple was that the high-contrast, film noir look should come from a high ratio of main light to fill light, but that the quality of the light should be softer, bounce light. However, once we started shooting, I decided a more controllable way to go was with direct Fresnels. Almost every shot in the movie was lit with either an laniro Miser, which is similar to an inkie, but tends to have a more even field, or a 4K HMI. It was a strange combination of extremes, but it worked for us. In fact, the extremes of lighting is what I like about the technical end of the film the most. In the end, there were no soft lights, bay lights, silks, and only a rare bounce light for scenes in the bathroom.

I am proud to say that the lighting in Blood Simple is almost totally unmotivated. There is a lot of discussion in the industry about motivated light (seeing the light sources in the frame), as if it is more truthful, honest, or more beautiful. For Blood Simple, the lighting was used as a psychological tool. For the film to be effective, the film had to be dark and contrasty. In fact, at the end of the film, the lighting itself becomes a character. The evil detective, in a bright bathroom, starts shooting bullets through a wall into a dark, adjoining apartment where our heroine is hiding. As each bullet slams through the common wall, light streaks through the darkened apartment at all kinds of crazy angles. By the time the detective runs out of bullets, the darkened room is sliced up into 30 tubes of light bleeding out of the six bullet holes, slicing at all kinds of angles, racing out in four or five different directions from each bullet hole. The only motivation for these crazy streams of light are 20 open-face 1Ks on the other side of the wall. However the audience is affected by the scene; it is funny and terrorizing, and it works.

Joel, Ethan and I felt strongly that we wanted our blacks to be rich, with no milky quality. The entire film was shot on 5293 rated at 200, which overexposed the stock between one half and a full stop. Our printing lights were always in the very high 40s. This produced a very thick negative, and although the raw stock is overexposed, the film is printed quite dark and contrasty, and the blacks are black. The development and answer printing was done at DuArt Labs in New York. My camera reports to the lab were always the same: “Print it too dark!” DuArt did a great job.

Jane Musky was the production designer. She created sets that were terrific and laughably inexpensive. That the film came in on time and on budget was due in no small way to Deborah Reinisch, the first assistant director and a film director in her own right, and Mark Silverman, the PM/associate producer.

As a cinematographer, Sonnenfeld went on to shoot the features Raising Arizona and Miller’s Crossing for the Coens, as well as Throw Momma From the Train, Big, When Harry Met Sally and Misery. As a director, his credits include The Addams Family, Get Shorty, Men In Black, Pushing Daisies and Schmigadoon!.

If you enjoy archival and retrospective articles on classic and influential films, you'll find more AC historical coverage here.