ShotDeck Drop: Body Heat

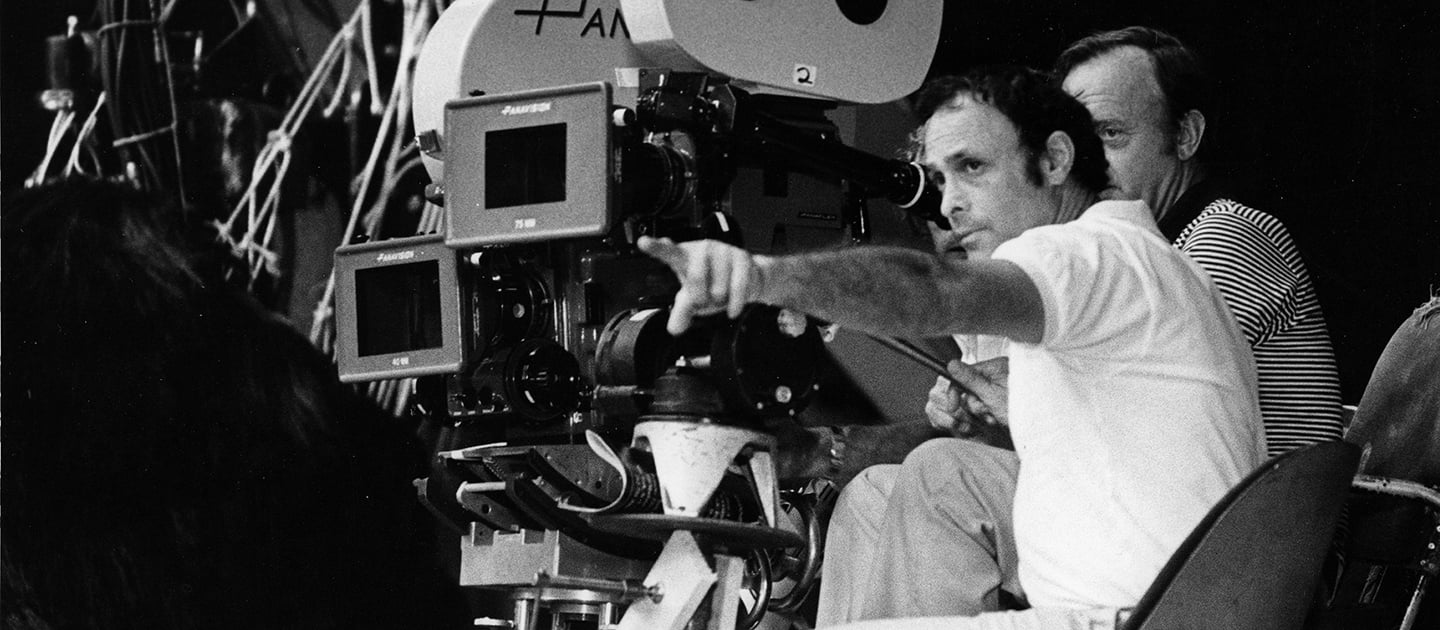

Photographed by Richard H Kline, ASC, Lawrence Kasdan’s directorial debut flirts with noir tropes and breathes new life into “that old feeling.”

The visual research resource ShotDeck recently examined Body Heat (1981), director Lawrence Kasdan's debut feature about a two-bit South Florida lawyer (William Hurt) who begins a passionate affair with a wealthy married woman (Kathleen Turner), entangling them both in a web of sex, lies, and murder. With influences ranging from Double Indemnity to The Conformist, Body Heat was singled out by critics for its direction, performances, and lush, colorful cinematography by Richard H. Kline, ASC.

Over more than 40 years as a cinematographer, Kline shot films of nearly every genre, as well as several that defied easy classification. Among his credits were Hang 'Em High, The Andromeda Strain, Soylent Green, Battle for the Planet of the Apes, Star Trek: The Motion Picture, Breathless, All of Me, Howard the Duck, and My Stepmother Is an Alien. He also shot several television pilots, including The Monkees. He received two Oscar nominations, for Camelot and the 1976 remake of King Kong. On the occasion of his ASC Lifetime Achievement Award, he told AC (Jan. '06), "I tried to never repeat myself."

The following dialogue is excerpted from the AFI Cinematography Seminar of February 6, 1982, with Kline in conversation with Howard Schwartz, ASC. It was preceded by a screening of Body Heat, and a longer transcript of the conversation was published in the August 1982 issue of American Cinematographer.

Howard Schwartz, ASC: How did you go about planning the way you were going to shoot the picture?

Richard H. Kline, ASC: Well, as you know, I don't work alone in a film, it's a cooperative effort with the director and art director, costume designer; it's not just a solo effort by a cinematographer. And this happens to be a film that was beautifully planned by Larry Kasdan and his associates. I executed it perhaps, but this was one of the most cohesive units I've ever worked with. Quite often you'll be on a project where — I hate to say it — where one element might be someplace else, not on the same wavelength. But in this case I must say the thinking was all in one direction, and that was Larry Kasdan, who very carefully placed everyone on that film. I think that's the reason for its successful look.

“I believe in the flexible method of having a direction to pursue, but not live or die by it.”

— Richard H. Kline, ASC

Did you guys have pretty thorough discussions before the picture as to the different style, the different look you wanted in different scenes, or was that more your concept from what you gathered from his general discussions?

By and large, Larry knew what he wanted. Even though it was his first directorial assignment, he's a very knowledgeable filmmaker. I swear, in his last life he must have been a director. He didn't quite know how to articulate it, but he knew what he wanted. And we just felt that at the right moment his desires would come out, or he'd be able to illustrate them either vocally or through something. But also his flexibility on the set was very well appreciated and, I think worked for him, because quite often some directors have preconceived ideas when they go. Some can even match sketches that were done months prior to filming, and use that as a guide or a security blanket or whatever you want to call it. Some are successful at it and some really fail. I believe in the flexible method of having a direction to pursue, but not live or die by it. Things happen on the set.

In most of your night sequences, did you print the blue in? Or, did you use the blues on the lights?

Combination. I did use some half blue, and then print the additional blue in. I have a way of working I can't do with all labs, but MGM does permit me to do it, and I mix the lights myself. I establish the CMY which they work with, the cyan-magenta-yellow, and I mix it as we go along so that in a long shot, I might want to put more blue than in a closeup, because of the face. I don't think the face should be too cool or too blue. It should be cool but not blue. So I will delete some blue out of it and I will mark on the report two points lighter or whatever — just put the numbers down.

Did you work fairly wide open on that stuff?

I would say.

This first sequence in the coffee shop, shooting against this window, now that's one situation where I would like you to talk about taking, in a sense, a calculated risk because of something you cannot measure with a light meter, how much it will blur into highlights into shadows. Is it just your experience or is it a way you can predict how much this blooming will happen?

It is experience to evaluate how much it will happen. And it can throw you, because it's contingent on what filters you have also in the camera, if they're low contrast or fog. And it's just the desired effect that you're going for too, how much you want to see out there. So it's a matter of judgment. You can't read it with a meter at all. But that's photography in itself: judgment. My personal feeling is you can go crazy reading a meter and get any kind of a reading you want. But it's an overall balance that really counts, and I think particularly in a case of a window blossoming.

What stop were you working at? Maybe 3.2, 3.5? Or did you go heavier than that?

That was quite a bit heavier... I think that's closer to 4.5, 5.6, as I recall.

It looked like it was blossoming so much I thought maybe you were, you know, even lower than... Normally I'd say 4.5 or something like that.

Yeah, but also you use the scale, too, the printing scale, to help that blossoming. First of all, the more you stop down the less blossoming you're going to have. So you want to control it, you would do it through exposure, too, and print at a different range.

In the night exteriors, when people would walk into the light. I noticed they had like kisses of light all throughout there. They were evenly lit. How did you achieve that, the placement of the lights?

Well, by placing, obviously, behind trees or objects. And quite often I'll walk a light if the camera is moving and the actor is moving, as an example, and say it's a 180 degree pan. In an open area such as the grassy area, you just can't hide lights. So we walk a light. And working at low light levels a man can carry a... 1000-watt lamp. And you can walk it and just float back and forth. That way it stays consistent.

I was just wondering about the highlights on the clothing.

It's good to make somebody just stand out a bit. It's like if you were drawing a picture, I think you would put that same highlight or something similar.

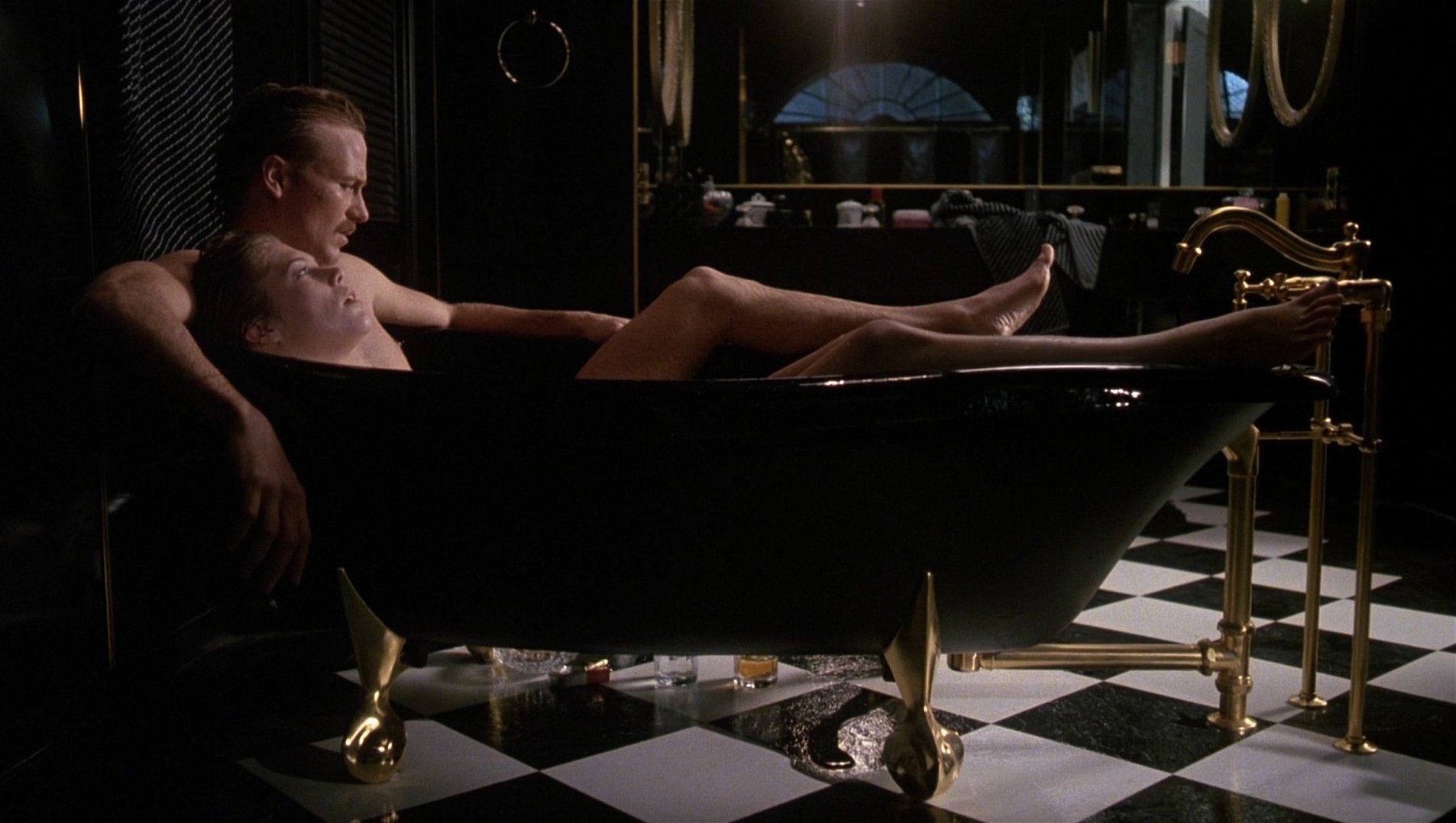

Were a lot of the interiors done at Zoetrope Studios? The bathroom and such?

Only his apartment. The house, the Walker mansion, was all done in Florida on a live location. But his apartment and one other little set, his office, those two sets were done [in Los Angeles], as I recall. Nothing else.

What were you using filter-wise?

Well, it would vary. It always had a filter. Either it would be a [Tiffen Low Contrast] 1 or 2 or 3, or a Fog Filter. I personally like the Tiffen Fog Filter. And that would also be a variation of 1, 2 or 3. It wasn't really overly heavy. A lot of this came through, I think the flaring or the softness came through exposure and lack of stop as opposed to heavy filtration.

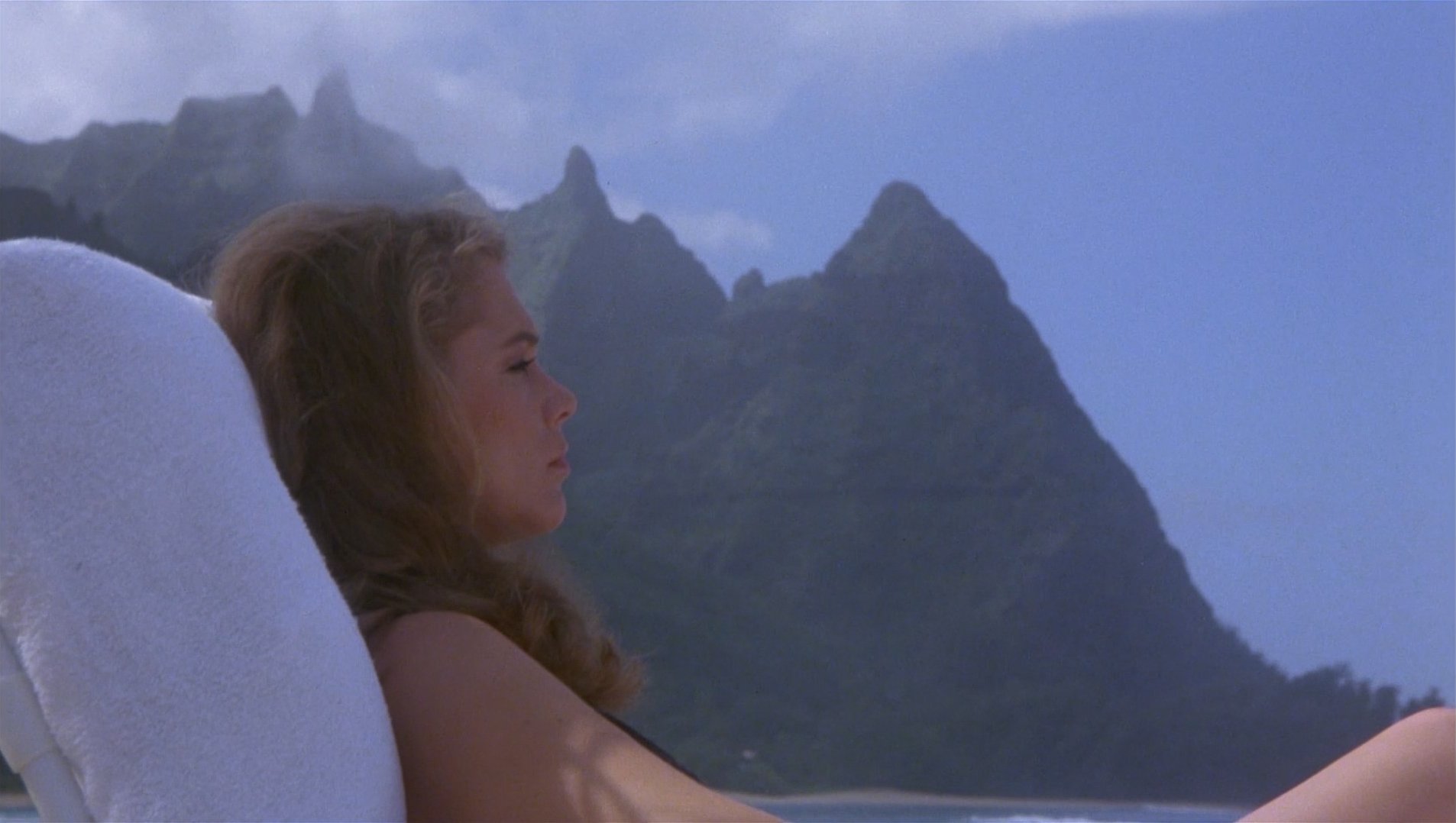

Could you talk about, in your preparation, about the look. Obviously it's a hot summer. People are sweaty. When you saw the script and started to think about how you want the film to look, what first came to your mind and how did it carry throughout the film?

Well, as an example, it wasn't sunny every day in Florida. We had terrible weather there. So the way to create this warm feeling was through filters, the color value on the light. I sometimes added a gel if I could, or did it in the printing. And they were continually being sprayed and it was very cold. As an example, there's a night sequence where they're on the pier. That was freezing cold. I was in my heaviest jacket and they were being sprayed down. He was in his skivvies, as I recall. I don't know how they braved it, but they did. A remarkable bit of avoiding goose pimples.

You mention that sometimes to add to your colors, you put a half gel on it, and sometimes you would add some in the lab. How do you determine how much color you're gonna add on the set and how much you're gonna add in the lab later on?

Well, it's easy to say experience, but each film is a new experience, and prior to the formal production I shoot tests, just my own technical tests, and I evaluate then just how much. I'll put a filter on the light. I usually know which filter to put on, but you never know. Things change or the batch of color that this filter came from might be a little different. It could be a different lab. Maybe if it were the same lab they might have changed some of their gamma. There's always some kind of variation. So I would test it and then various stages of applying more blue or less blue if I want it to go blue. Or, in a case of warming up a scene I would use yellow or red combinations. I have all this in my mind prior to the filming. And then I would, like a surgeon, know which tools I have to work with and apply them at the right moment.

The assistant cameraman has to keep a very detailed report. Labs work under a tremendous handicap. If you give them the privilege of timing a scene, they're guessing really, unless you're there to tell them every degree of look that you're after. They're a little bit jaded, also. They see thousands of feet of film a day, and at the worst hours. They work like milkmen or night taxi drivers. So that's why I've opted to do the mixing of the lights myself, once I've established them. But I shift them. Each cut might be different, might not be the same light. But I have what I call a normal. As an example, 30-32-31, which would be the cyan-magenta-yellow combination. I might take a point of yellow out on one, on a closeup. Or add a point of yellow for the blue, or alter the blue. And having made my test prior to the film, I would know exactly what to do.

And also, each lens they're not perfectly matched. We try to match them as best we can when we select a camera for a film, but some are cooler, some are warmer. I evaluate that prior to the filming. I test each lens separately. And so I know that a certain, 75mm lens might be a little cooler, so I'll add a little warmth to it, like a yellow. A point of yellow might just even out everything. That's how I play with the lights — I should say the printer lights — and try to keep total control of the color.

How often did you get to see rushes in Florida? Did they ship 'em back there, or...

Yes they did. We'd see them three days later, three to four days later, which is after the horse is out of the barn — but I had daily contact with the lab. You have to keep the lab honest, let them know that you are watching and that you are very careful, or else they might get sloppy. They have a thankless job in many respects. I call them every single day. Just a brief conversation. They know what I'm looking for. As an example, technically, there could be a scratch, something that you'd want to shoot right away and not wait four days later to find out. Or there could be an out of focus shot; not only just the photography but there are other aspects they they could comment on that could be helpful to a film.

There's a long shot the first time Ned meets Matty at an outdoor amphitheater, in an outdoor concert. And the audience is lit very, very warm. And then she comes from that into a cooler lighting and William Hurt is in the foreground and he's also lit very warm. There's a moving in and out of that cool light and very warm light with cool kicks on him. How much of that is done in the printing of it and how much is done in the shooting of it?

That was a challenging scene, the reason being there was a 50-mile an hour wind blowing. Seriously. And we had to finish. We were behind schedule and losing... well, it's the economics of filmmaking. So, a clever production unit brought in about 20 or 25 large trailers, and lined them up and almost stacked them — it was an amazing thing — for a windbreak. Took half the night to do it. All of a sudden the wind came up and it hit 50 miles an hour, like a gale. I don't know if you noticed a lot of hair blowing, but we were holding up boards and 5-ply and whatnot. So I was very handicapped as far as lighting was concerned because it was blowing all over the place. And I had to use large units there, which I prefer not using. Like one large unit to light and then some little highlights. And it was very difficult to put gels on the lights because of the blowing. The lab did a lot of that for me. That was a very difficult sequence. It didn't show it though. You'd never know.

Were there blue gels on certain lights and warm gels on other lights?

There was an arcade behind them. In the arcade I had normal incandescent light and possibly some of them had a very slight yellow gel, because they were protected from the wind and I didn't have to worry about it. But for the overall light I think I put one gel on that, a very light half blue. Lee Blue is what I generally use. Rosco makes the same thing. So I used very few gels on that and did use the lab to mix the color.

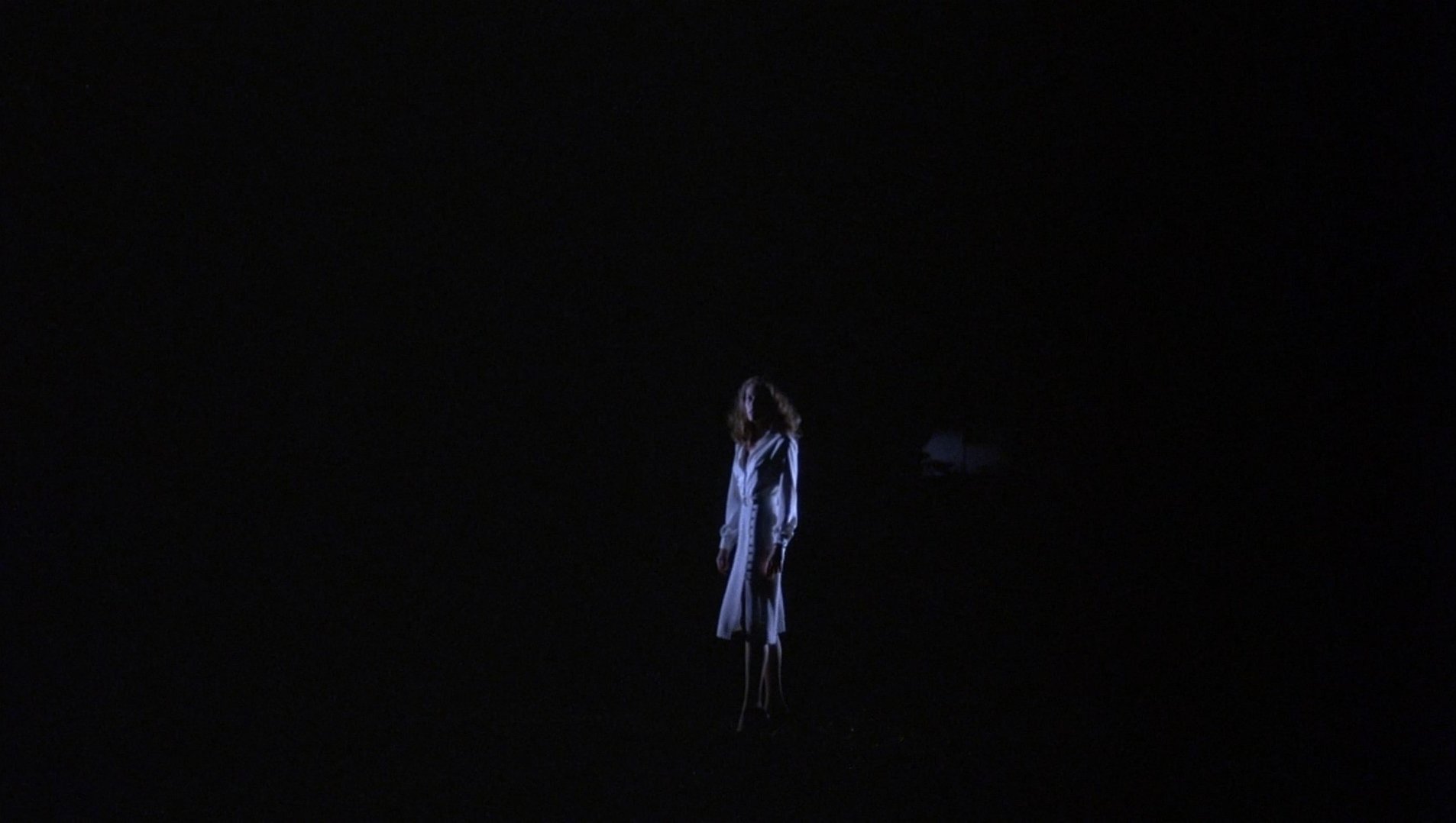

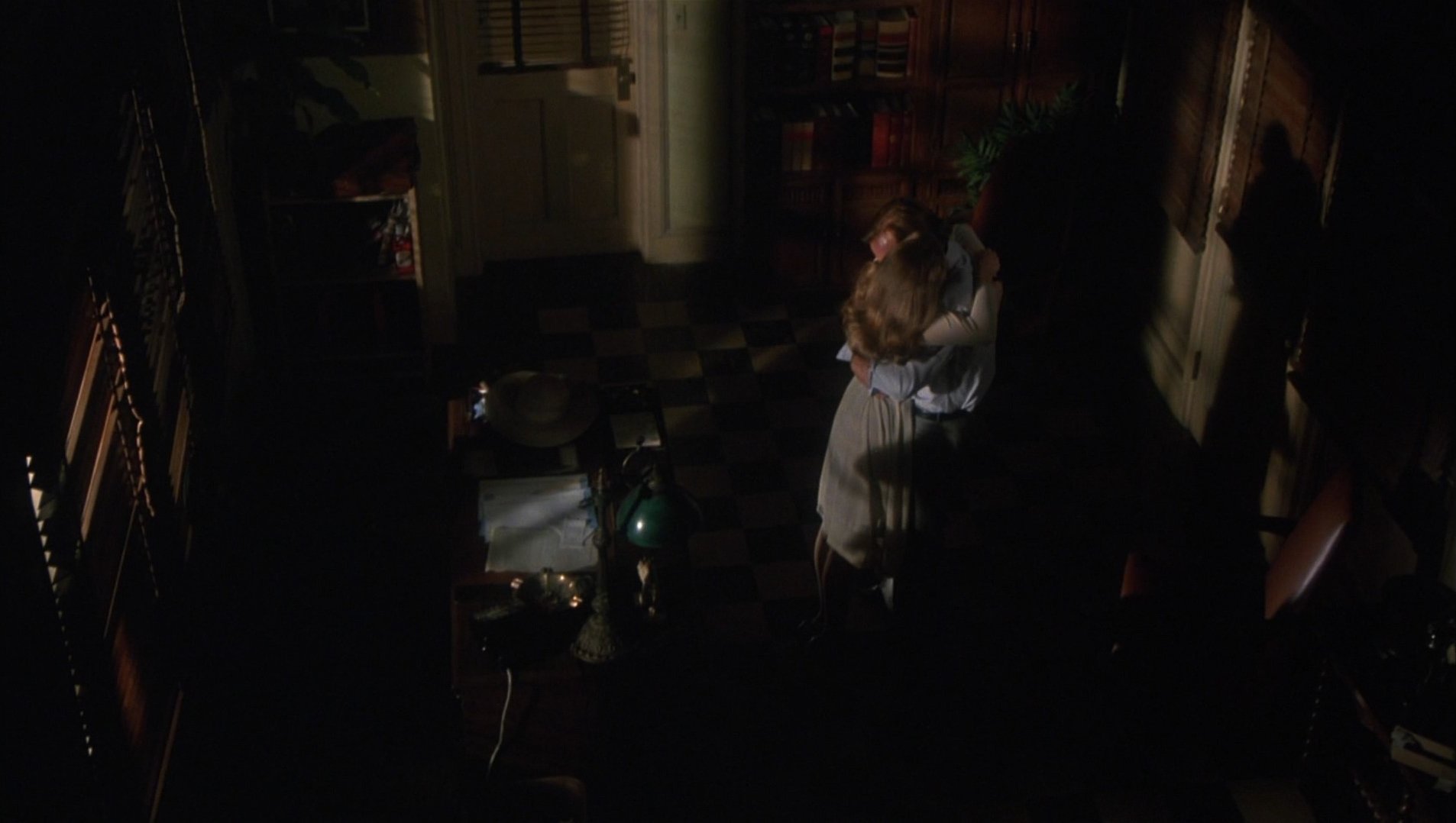

There were two scenes that really drew me into the film. One was the long pan up the staircase when he first goes into her house and they walk up to where it fades almost to where you can't see them at all and then they come back up and the light comes on. The other is where she was at the end of the dog house, a bright beacon of white in the midst of all this blackness. Were there any special things about shooting those, or any problems lighting them?

Hiding the lights was the big problem. But that was poetic license where she just disappears into nothing, and that was planned. If it didn't work it would have been a real problem. And you don't know until after the fact. And it could have been hokey. I think it worked there. The other one going up the stairway, was that when he first arrived at the house? They turn a light on down below near the doorway. And they walk in the shadows, up the stairs. She's turned on the light upstairs. I just felt that was a natural source and lack of source — I should say lack of light — as they walk away from the bottom lamp, they diminish. The light source diminishes as they go up the stairs.

What kind of lighting did you use on that?

The tractor light below had a regular globe in there, but I used 1K units basically, and some bounce. I would take another 1K off of foam core and bounce it for just a general fill, call it a reference light, and when they walked up the stairs they would get into that bounce light and it would diminish as they got further away from the source which was below. And then she hit the light upstairs.

How precise is your previsualization of a lighting setup?

I rarely even read a meter. During this rehearsal I try to take just five minutes or so and light key lights. Like, if it were a room I would light the exterior. Just throw a source through. Or, if it's a night shot, I would kill the overhead lights and light a lamp, if it were to be lit. So that during the rehearsal you get accustomed to a mood that could be the mood you will utilize during the filming, during the lighting. And so now, during the rehearsal I think we all feel it. It might be entirely wrong when you see how the rehearsal came out. So the flexibility of the director working with actors has a bearing on how the look will be. So I do not say "200 foot candles." I might resort to that when my camera assistant says, “I cannot carry the focus from here to there.” Then I'll do something, I'll build up. But I try to be as natural as possible and photograph this exactly as it is.

The scene in the beginning where you see the fire in the background out of the window...

That was a miniature on the stage, just a little flame of light about a foot-and-a-half high. As you know, Zoetrope is a very small studio and we were pinched. And then we had cutouts of streets, houses, and some real greenery, with fans blowing it so it did look real.

You know the shot where he puts on the hat and the window rolls up? What did you do?

It was very simple. I had a shutter on two different lights: her in the car and he's standing outside. As the window was raised I would dim the shutter on her, on Kathleen, which made her dark and made a mirror out of [the window], and then bring up the light on him. So it was just a matter of one off, one on.

I'd be curious to know if the shot in the office, after they decide they're gonna murder [the husband], when you go way up on it, if there was any sort of thought from your part or Kasdan's as to why bring it up so high looking down like that.

It's funny you should mention that. Larry had a desire to do that. And he was fought. First of all, it's an old studio, Zoetrope, and it couldn't accommodate the crane to go that high; the cranes are quite heavy, as you know. And so they tried to discourage him, telling that we'd have to shore up the floor. But he fought for that shot, and it really was effective. That goes back to what I said about Larry; something about just the feel of going up...

Like her disappearing in the mind.

Right. There was something — an instinct tells you. That's why pre-planning can be so dangerous, but then again, it can work for you, too. And in this case it really did work for him. I think it was magnificent. Yet, I can't tell you why. It's just a feel. And I think that's what filmmaking is, providing you have the time. Feel is very important.

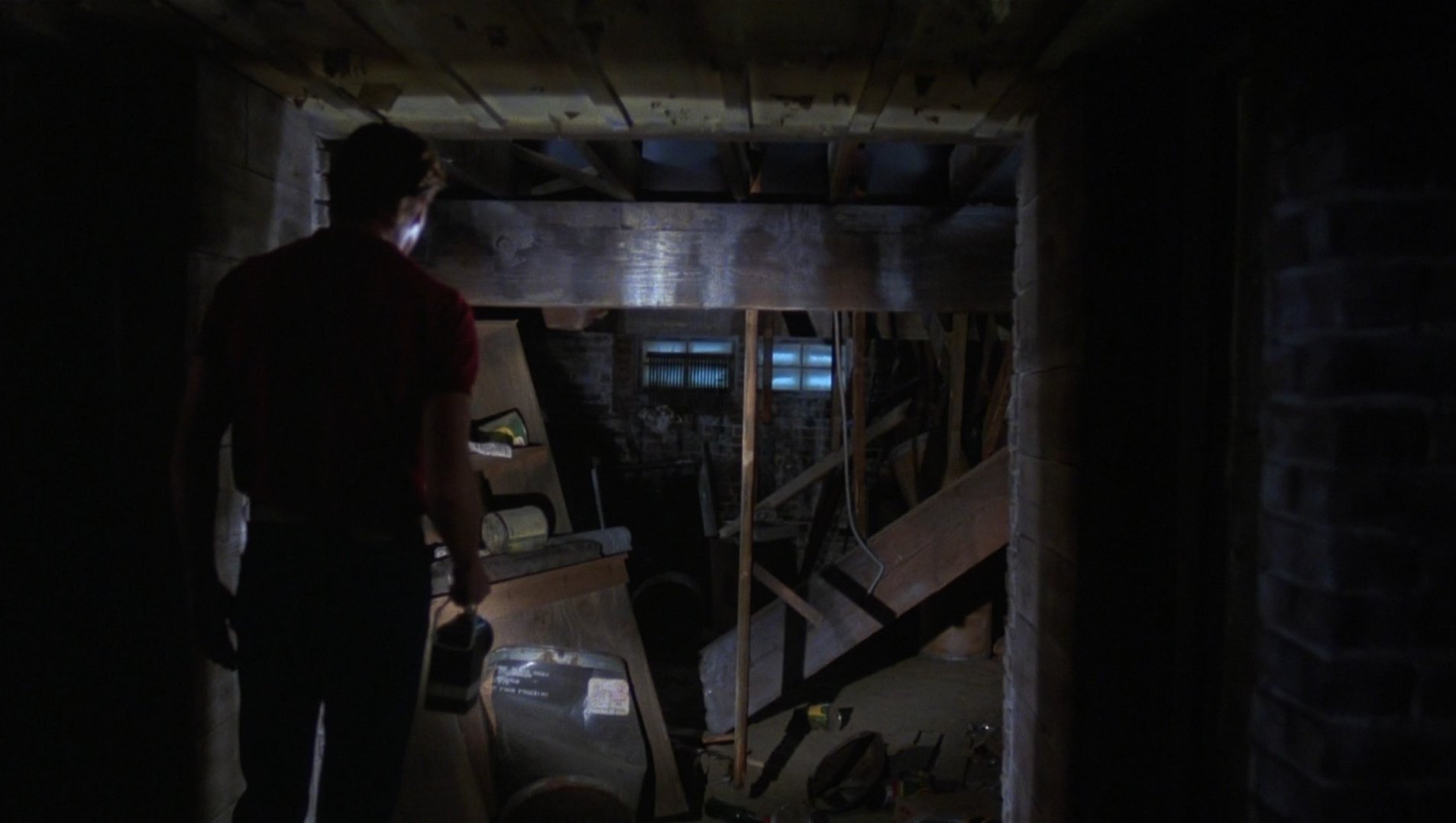

How did you rig the back door with the flashlight in the basement of the warehouse?

That was a hot shot flashlight. I used that same flashlight on King Kong, the ones they used in the jungle. He wears a hidden battery. It was squared rather than just the little dot of light. I know it's not unnatural to have a dot of light but it doesn't read well, and I like a large spread. The whole shot was lit with that. It just had a reference light and then that lamp itself illuminated the whole scene. It's a projection globe out of a Sawyer projector. It's about three inches in diameter, it's one of those quartz halogen lights, and it gives out a tremendous amount of light. It happens to be the right Kelvin. I carry it wherever I go.

When you blew up that first incendiary device, did you actually blow that up?

We did yeah. We had two cameras, and it was just one cut of the explosion and that was it. An effects person did that. He was a good man. Oh, when the boathouse blew up at the end, three cameras were trained on it: one going at 48 frames, and the other two normal. You can only do that once.

I noticed in the jail scene, when he was talking with the officer who arrested him, the camera movement went around him to one side and back around to the other side, and so forth. I was wondering about the motivation for it, whether it was, again, those feelings that maybe the director had, or you have.

The dialogue really wasn't the most sparkling dialogue, and it had to be just flavored a little bit. And that, I believe, did it. We knew it was a long chunk of dialogue, and something had to be done. It was discussed before, but the finalization was right on the spot. I would say it was done from feel.

Getting back to the color temperature of your lenses and different temperature of cooler and hotter, how do you actually see the different colors? What do you look for?

Well I shoot a test... with a neutral background. I always get a neutral flesh tone in there, somebody without any makeup, preferably. And set the camera roughly six to ten feet away. And light it just once. Then I shoot every lens at the same stop, and have it printed on the same light, and that way you run it together and you can see if there's a difference in color value or stop. You can test the lens thoroughly that way. You also check it for focus and other defects.

In preparation for color correcting the lenses, do you do that by using slides behind the lens? Or do you have the lab correct that for each?

I do that myself. If I deem that a certain lens is not the right color, is not in keeping with all the other lenses, then I make the correction with the lights, not filters. I try to put as little in front of the lens as possible. We really use nine lenses plus a zoom. It's easy to remember that a 25mm or a 50mm is a little bit on the blue side, so you add a drop of yellow to it.

“I liken my relationship to a director like a caddy is to a golfer... We know the course better sometimes.”

How closely did you work with Lawrence Kasdan? Is he in the camera a lot? And do you encourage directors to do that? Also, could you comment a little bit on working with operators? Are these operators you've worked with before, so that you say well this is the opening frame and that's the end frame it’s double shot and you can just sit back and know that it’s happening.

I don't operate myself, but I do design the shot with the director. And my operator [Albert Bettcher] — we've been together many years — has marvelous antennas. He hears everything and he can emulate what we're after. And he's so good he'll take the first rehearsal and I know exactly that he's getting what I intended it to be. But during the lighting I light through the camera. But if while I'm lighting I see something that could be beneficial for what we're after, I'll call Larry over to look through and see, to get his opinion. He might agree or he might not.

I'm curious about the communication between you and Lawrence Kasdan, what he said to you before production, how he wanted the overall look, and specific scenes that he said he wanted in such and such a way, and if you think what's up on the screen is what he wanted.

Well, there never was anything specific in all of our pre-production meetings, but we looked at some films together, old films. We looked at some Kurosawa films. We looked at High and Low, 'cause I think we're all [Akira] Kurosawa freaks. This is not unusual to run films with directors just to get a kind of a meeting of the minds and see if we think on a parallel line. But the film I like is [Bernardo] Bertolucci's film, The Conformist [shot by Vittorio Storaro, ASC, AIC]. I find that Bertolucci is a master at variation, a variety of looks within a film. And I try to do that myself. That is why I usually recommend seeing The Conformist.

And another film that I like is The Third Man, which I think is one of the most brilliantly appointed films ever made. I once worked with George Cukor, who had a phrase: “Be daring but don't get caught at it.” And I think they did that. They were daring in that film and they didn't get caught at it. And quite often people are caught at shooting through the armpits and things like that.

I liken my relationship to a director like a caddy is to a golfer. Quite often we can make a recommendation as to which club to use. We know the course better sometimes. And even though he does the shots and it's his thinking, while he's swinging we might see something maybe he should have followed through a little more. We can whisper to a director, rub shoulders... It is that kind of relationship where I think actors, too, confide in cameramen and directors... It's a great challenge. So we accommodate them, we look out for whatever we should be looking out for. Hopefully, we are there to collaborate, and not just work for. And I feel that way about my whole crew; we all collaborate.

Founded by Lawrence Sher, ASC (cinematographer of Joker: Folie à Deux, The Hangover Trilogy, Garden State), ShotDeck is the world’s largest library of fully-searchable high-definition cinematic images. With over 1.6 Million shots and now an App for iPhone and iPad access, ShotDeck is an invaluable reference, planning, and collaboration tool for filmmakers, students and creatives of any kind.

Each week, ShotDeck makes hundreds of new, high-quality images available to users. AC will be regularly examining these projects with additional context and input from the cinematographers and other filmmakers involved in their creation.