Sinister Sect: Spectre

Hoyte van Hoytema, FSF, NSC combines classic and contemporary styles for the latest James Bond film.

Daniel Craig stands on a narrow ledge some 30' off the ground. A security cable stretches out the back of the actor’s elegant jacket and fastens to a point roughly 20' above, where a crewmember monitors the rig attentively. The set comprises four walls of a blown-out building, and the action is a simple gag: 007 grabs at a light fixture on the wall to steady himself, the fixture comes off, and he falls on the ledge. Director Sam Mendes yells, “Cut!”

AC is visiting director of photography Hoyte van Hoytema, ASC, FSF, NSC and his crew on the backlot of Pinewood Studios, on the set of Spectre, the latest film in the long-running James Bond franchise. Filmed by a Technocrane-mounted Panavision Millennium XL2 camera, Craig performs several takes in this perilous position, and when at last the scene is done, he descends and introduces himself, adding, “You have to put our film on the cover of American Cinematographer!”

We joke that Bond might get the cover if Craig provides an exclusive, tell-all interview. The notoriously private actor responds with a good-natured smile and goes back to shooting. We’re pleasantly surprised, however, when he does return to offer his thoughts about the importance of shooting on film. “As far as I’m concerned, nothing beats shooting on 35mm film,” the actor opines. “Film is so much more beautiful than digital; it gives so many more textures and variations. I don’t know very much, but the amount of work that goes into working on digital to make it look like film after the event seems like a great waste of time. Why not just shoot on film?”

Indeed, if there’s a single theme that emerges from our time with van Hoytema, it’s his unconditional devotion to film negative. After the production wraps, the cinematographer kindly invites AC to appreciate the film’s grain and texture during the DI at Company 3 in London, where he reads amusing statistics about the production sent by 1st AC Julian Bucknall: “The Spectre camera crew used 30 cameras, 280 lenses, consumed 1,800 espressos … and almost a million feet of film!”

The cinematographer used three Kodak Vision3 negatives on Spectre: 50D 5203, 250D 5207 and 500T 5219. The dailies were transferred on a Spirit, and the negative selects were rescanned at 4K on an Arriscan. The DI was graded by colorist Greg Fisher, who worked in 4K using Blackmagic Design’s DaVinci Resolve.

AC’s interview with van Hoytema was complemented by discussions with Fisher and Panavision’s Dan Sasaki. A special thanks goes to gaffer David Smith for taking time to detail the lighting setups, and to Heather Callow for coordinating visits to the set and DI suite.

American Cinematographer: What indications did director Sam Mendes give you about the visual style and look of Spectre?

Hoyte van Hoytema, ASC, FSF, NSC: Sam wanted the different [points] on Bond’s journey to have a distinctive feel. They all had to carry a specific mood, suitable to the location and, of course, the story. The visual language of the film wasn’t something that had a certain mandate or rulebook attached to it from the start but was something that evolved as we moved forward. It was a very organic process of eliminating what felt wrong, and adding what felt appropriate.

How did you decide to shoot film negative?

I suggested film from the start, but I think that Sam had been living with the same thought. I had the feeling that Sam really had a great interest in finding a medium that his cinematographer was comfortable with, and I have always felt his respect regarding the choice.

Why did you choose to shoot anamorphic?

Shooting anamorphic for a project like this is a no-brainer. However, we also played around with the thought of shooting Imax, and I did extensive testing. But it became impossible for us to pursue Imax on this kind of scale — we shot almost a million feet, and our second unit sometimes used more than seven camera bodies simultaneously — so we decided on 35mm anamorphic.

What was it like working with Mendes?

I enjoyed every moment with him. Sam is smart, witty and a pure film craftsman. He is very knowledgeable and is genuinely interested in all the aspects of filmmaking — a fanatical storyteller. Sam told me once that, within the whole machinery of filmmaking, cinematography was very close to his heart. I can confirm that. His love for cinematography created great companionship, trust, and access. There is a classic feel to the look of Spectre.

How did you and Mendes arrive at that style?

We wanted it to feel more romantic and more classic. Since Bond used to be a style icon, I was wondering if we could get some of that old-fashioned flair back but in an effortless way, not having to try too hard, without feeling forced and unnatural. Bond never really has to prove himself, and I wanted to reflect that effortless feeling in the visual language. I believe that we got more powerful results by being more settled and restrained.

How did you and Mendes work together to define the camera angles and movement?

We tried to place the camera exactly where it’s supposed to be, without trying to jazz things up by putting it in weird positions or complicated moves. We wanted camera movement to be functional rather than decorative. In the action scenes, we were very meticulous about screen directions. It’s important that the viewer is able to understand what’s going on. As a result, you can cut very fast, but you don’t get confused, and the film can be punchier. This is something I never used to do and is very much due to Sam.

And there is no slow motion?

Hardly any. Once again, the idea was to have no unnecessary decoration, just to focus on the story. There’s a phrase by Goethe that I like a lot: ‘So fühlt man Absicht, und man ist verstimmt,’ which translates roughly to: ‘As soon as one becomes aware of the intention, the senses are numbed.’

You’re not used to working with a camera operator?

I have worked with operators, but I always did the handheld — it has always been a very personal and organic thing. I remember in the beginning of this film, when [A-Camera operator] Lukasz Bielan operated a scene, I looked at what he was doing and I thought, ‘Oh, it’s so nice to have an operator who is better than I am!’ It made me very comfortable and helped me to handle the magnitude of the production. Sam and I would talk a lot about the mise-en-scène and which lenses to use and so on, but Lukasz was always there, listening in the background, and he added his energy and ideas.

How was handheld employed in the movie?

There are very formal parts in the film, but there is also a sort of warm-blooded storyline that starts to evolve with James Bond actually falling in love! We felt that it was interesting to gradually step away from the formalism, to loosen the camera up a little and add some handheld in those scenes.

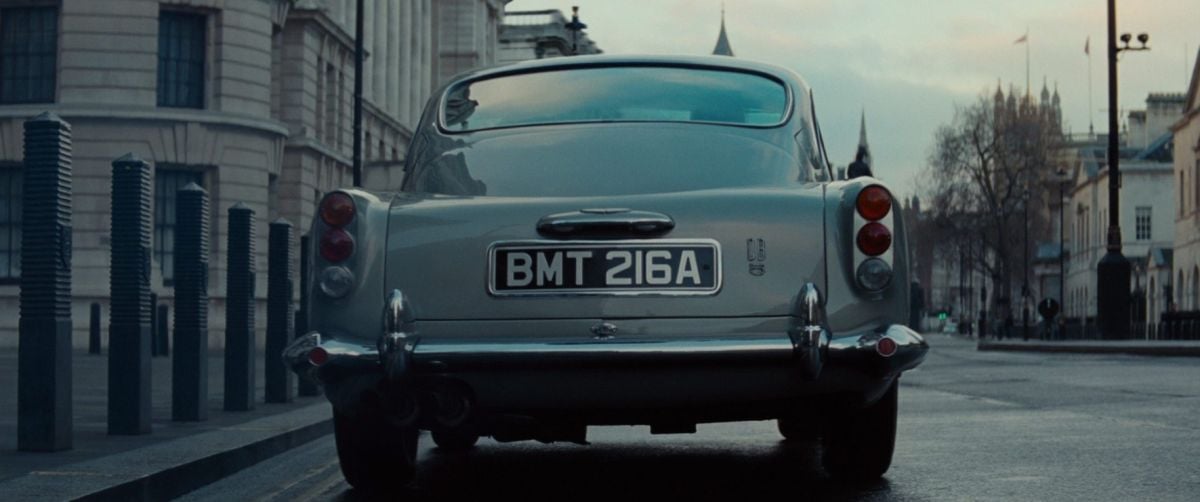

But in the action scenes, like the car chase in Rome, we wanted the frames to be more elegant and settled. We wanted to convey speed without shaking the visuals. So we had the camera mounted to the car, and we used a Russian Arm a lot.

Although the camera feels classical, the lighting is more contemporary. For example, there is no fill light.

Exactly. We wanted to give the film a retro feeling, but that doesn’t mean making a retro film. So we used very modern elements and technology, with a slightly old-fashioned ‘laid-backness.’ It’s a mixture, a blending of both worlds. In general, I’m not big on fill. I love the idea of just putting the light source in the right place. There have been [Bond films] in the past where his face is lit in the same meticulous way in different scenes: a ¾ frontal with a little bit of fill. When you find the perfect light for a face all the time, you step away from reality. For this Bond I wanted close-ups to have different feels, and I also used different tools: RifaLites, fluorescents, LED panels.

I like to do dynamic close-ups, where the light on the faces changes because of the mise-en-scène. For example, when Bond and Madeleine [Léa Seydoux] are in the back room of the hotel in Morocco, they’re standing in half-darkness, in a very soft ambient light, and then they have a confrontation as they step into the light of an overhead lightbulb hanging above a table.

The Day of the Dead opening sequence in Mexico City is shot without direct sunlight, and with a lot of smoke. That gives the day exterior a unique look.

We wanted to make Mexico like an exotic, strange dream. We would literally wait for the sun to disappear, add smoke and shoot. We added a lot of smoke, because we really wanted to disperse the light, to make the air feel heavy. We shot in Mexico in [4-perf] Super 35 with a combination of the 50 and 250 [stocks].

We tried to shoot everything in Mexico overcast, but we weren’t always successful; there are parts where the sun breaks out. We wanted to reserve direct sunlight for Morocco.

Why did you shoot Mexico City with spherical Primos instead of anamorphics?

I wanted to make the image a little softer and grittier, as well as help visual effects with some extra negative at the top and bottom to assist with their transitions for the master shot. Spherical always feels a little more rounded off; the edges are taken off a little bit. Anamorphic is so much sharper.

Some people feel that spherical is sharper than anamorphic.

Not if you’re working with extremely well-tuned anamorphic lenses. A good anamorphic lens has much better resolution in [2.39:1] than a Super 35 image. But it’s very hard to create anamorphic glass that is good, so it’s true that you come across a lot of lenses that feel soft. People often use anamorphics in commercials to make soft images with lots of flare. [ASC associate and Panavision’s vice president of optical engineering], Dan Sasaki, tuned our anamorphic lenses so that flares don’t occur as much in sunlight, but they do occur in artificial light.

For the [nighttime chase scene in Rome], we used a big collection of lenses. Our workhorse set [for these sequences] was actually the Arri Master Anamorphics, to avoid extreme headlight flares and still be able to shoot in low light, as they are a [T1.9] across the set. All the other [footage] in Rome was shot with the Panavisions.

This playfulness with the formats, mixing spherical and anamorphic, is very much a part of modern filmmaking.

I think so, too, and I love it. The mantra that I got at the classic film school in Łód'z [Poland] — and also read in old American Cinematographer interviews — was that it doesn’t matter what you do as long as you’re consistent. I take pleasure in trying to be inconsistent!

How did you light the interiors in the Roman car chase at night?

The car interiors were shot on a stage with a mixture of rear-screen projection, LED panels and classic light gags. Rear screen disappeared because of greenscreen, but the big problem with greenscreen is that you’re always lighting the foreground and background separately. Rear screen gives you reflections in the car and light on people’s faces that you wouldn’t get with greenscreen. We added rotating mirrors and classic light gags with moving panels to sell the effect. We also fed the content of the rear projection to bright, low-resolution LED screens and used them off-camera as a light source.

You used Translights a lot on your sets.

I’m very much for doing things in-camera. I want the images to guide post more than the other way around; that’s why I like to use Translights. I love to create environments on the soundstage that are as realistic as possible for the actors. It’s such a wonderful feeling to have actors walk on to a set and start settling in as if they’re really in a location, without having to use their imagination.

That’s also the reason I love working with low light levels, and why I love to keep my lights outside the set. Even on a soundstage, I like to have my sources come through the windows. I try to have as few lights on set as possible, because they break the magic — they pop the balloon.

The night exterior along the Thames required an epic lighting installation that only a James Bond film could get away with.

It’s the biggest lighting setup I’ve ever done, and it might be one for The Guinness Book of World Records! It took five weeks to set up. My gaffer, David Smith, and his crew set up eight construction cranes and two floating pontoons on the Thames, plus dozens of other fixtures on the shore. We had 28 generators.

[Editor’s note: The full lighting rig for the Thames shoot included 30 20Ks, primarily on rooftops; eight Full Wendys on cranes and barges; 24 Quarter Wendys, mainly on rooftops; 25 T12s, rigged on rooftops and on stands along the water; 16 10Ks, 12 5Ks and 50 Blondes, mostly on stands along the river; and 150 1,250-watt Atlas fittings, which took a crew three weeks — working at night — to rig beneath the bridges.]

Why did you do the DI in 4K?

2K is not enough resolution to render the shape and depth of the grain. I love grain. It’s very organic; it feels round. In my opinion, if you render grain in 2K, it turns into noise — some sort of digital interpretation of grain.

You feel that you need the 4K to render the grain even though you’re going to go back out to 2K later?

Yes, it’s better to oversample. It’s a lot of data, but it’s totally doable. To be honest, I think it’s quite strange that the 2K workflow has held on for so long. For a lot of post houses, it’s cheaper business-wise, but I think that the 2K format is not going to last, because it’s not enough resolution.

Making a film involves so much collaboration. Gaffer David Smith, colorist Greg Fisher, and Panavision’s Dan Sasaki have given us important production details. Who are some of the other people you would like to thank?

I owe so much to so many! Operator Lukasz Bielan, AC Julian Bucknall, second-unit director Alexander Witt and cinematographer Jallo Faber, production designer Dennis Gassner, and also Hugh Whittaker and Charlie Todman from Panavision and Rob Garvie from Panalux. My key grip, Gary Hymns, was a fantastic source of energy. No matter how stressed or gnarly the situation was, in the heat of it all, he would turn to me with a glint in his eye and say, ‘God, I love this job.’ I thrive when people around me have that kind of love and energy!

I also have to thank Sam. He has an awe-provoking command over every aspect of filmmaking, yet he puts a lot of trust in his co-workers, and he is very secure and humble about letting people influence him. Sam Mendes is a director in the most complete sense of the word.

- 2.39:1

- Anamorphic 35mm, 4-perf Super 35mm, Digital Capture

- Panavision Millennium XL2, Arriflex 235, Arri Alexa 65

- Panavision C Series, Primo, Primo 70; Arri Master Anamorphic

- Kodak Vision3 50D 5203, 250D 5207, 500T 5219

- Digital Intermediate

American Cinematographer: Can you talk about the huge Austrian-spa set in Pinewood?

Hoyte van Hoytema, ASC, FSF, NSC: The building was three stories high and mostly glass, and a Translight background of snowy mountains went 360 degrees around it, from floor to ceiling. To get convincing Translights, you need big sizes and distances. The glass panes in the building also helped here, because we got reflections of the Translight from all sides.

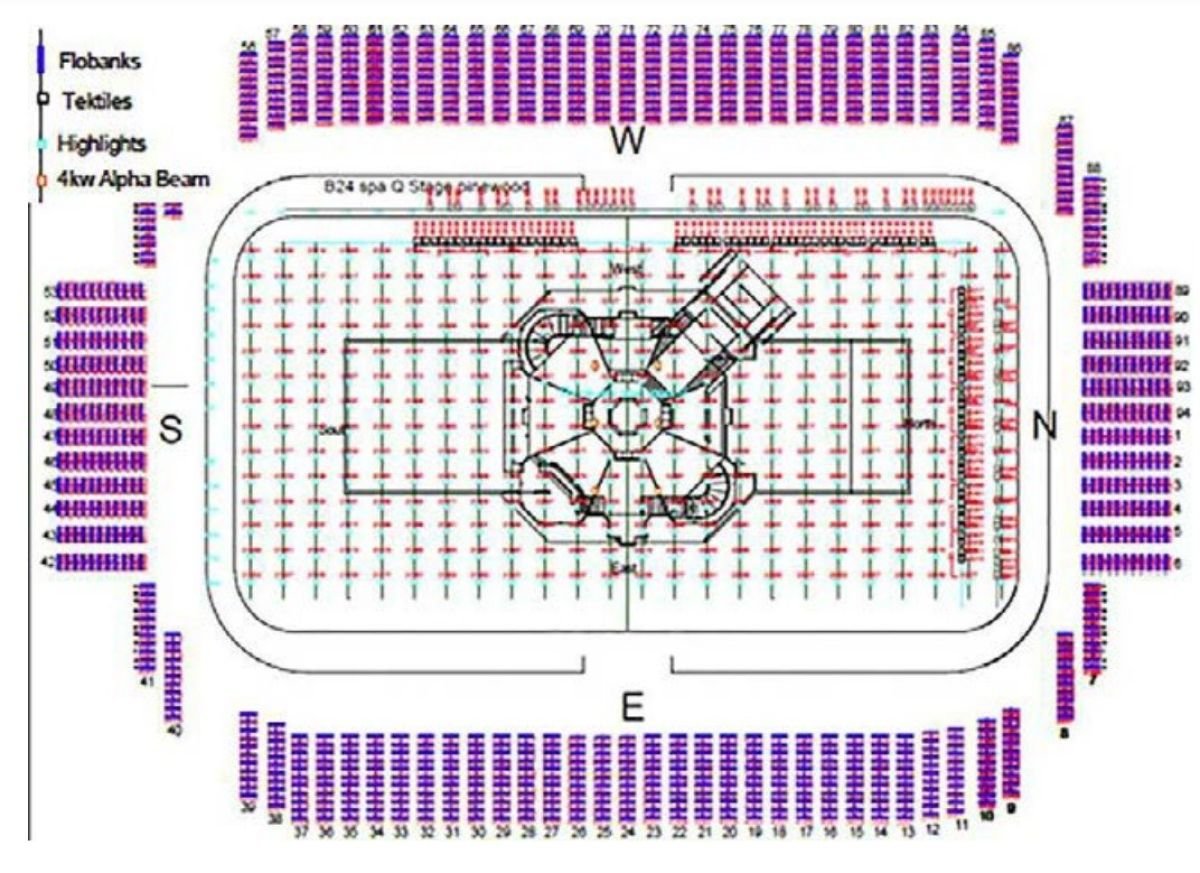

How did you and gaffer David Smith light the Translights for the spa set?

Van Hoytema: The scene was meant to [take place on] a clear, overcast day, so I wanted to light it with daylight sources to be naturalistic. With a big Translight, you have to take temperature into consideration — with tungsten or HMI lights, the stage would have become unlivable. Also, we couldn’t use big light sources behind [the Translight] because we had to keep the footprint as small as possible. So we made a giant rib of fluorescents all around the set.

David, could you detail the fixtures used on this big glass set?

David Smith: Everything was daylight-balanced. All the fluorescents and LEDs were fully dimmable and DMX-controlled. We used Panalux FloBank fixtures behind the Translight; FloBanks have two groups of four 54- watt tubes.

To give an overall ambient light — and in case we saw reflections of the ‘sky’ in the glass — we had a silk above the set roof with Panalux HiLights lighting from above. The HiLights have eight 55-watt tubes. We also had rows of [Panalux] 2-by-2 LED TekTiles to give a sense of light direction from the two ‘brighter’ sides of the building, and we had six K5600 4K Alphas beaming down the central atrium, which we used because you can [position] them pointing straight down.

Not pictured on the diagram are 16 18K Arrimax Pars that we moved around on the floor of the stage outside the building. They were aimed at Ultrabounce frames on trusses above the Translights. We could lower and angle the frames as needed with electric motors to get a soft daylight key into the building.

Although Hoyte van Hoytema, ASC, FSF, NSC is a confirmed film aficionado, he decided that, due to the extremely low light levels, it was more prudent to shoot Spectre’s nighttime boat chase on the Thames with a digital camera. He opted to shoot with Arri’s recently introduced Alexa 65 because of its resolution, and he wanted to pair the camera with Panavision’s new Primo 70 lenses because they open to T2.

ASC associate Dan Sasaki, Panavision’s VP of optical engineering, explains that Arri Managing Director Franz Kraus and Panavision CEO Kim Snyder — both of whom are also ASC associate members — agreed to work together to deliver this cross-company equipment package to the Spectre filmmakers.

American Cinematographer: Putting the Primo 70 lenses on the Alexa 65 involved a historic collaboration between Arri and Panavision.

Dan Sasaki: We had a dinner together when we finished, and Franz Kraus commented that, for years, neither of us would have allowed a competitor’s employee into the building!

We had a great collaboration with Arri. A small team from Panavision went to Munich prior to the principal photography of Spectre to ensure that the adaptation of the Primo 70s for the Alexa 65 went well. We met with the Arri design team and we found some optical problems because there were a lot of unknowns. So we did some research and development there to figure out what we needed to modify or change. Everything worked out very nicely, and things went pretty smoothly for Spectre.

What kind of modifications did you make?

The Primo 70s were developed for a different optical low-pass filter scheme than the Alexa 65s, so we had to include compensation elements in the optical path behind the lenses. This was on the adapter inside the camera. We also changed some coatings.

Did you do any mechanical modifications?

Arri made a universal base for the Alexa 65, which made it adaptable to our Panavision 70 mount. So we made half the mechanical coupling and Arri made the other half.

What were van Hoytema’s requirements?

The fact that the Primo 70s performed well at T2 was very important to Hoyte. He was happy with the way the lenses handled flares and random glare during his initial tests, but he was shooting down the Thames where he didn’t have control of all the lights, and he didn’t want unforeseen surprises showing up. So we did another battery of tests to look at the flare and glare, and that was another factor that prompted a change in the coatings to a much higher tolerance than we originally had.

Will there be more projects pairing the Primo 70s and Alexa 65?

Yes, for example, Passengers, an upcoming film to be shot by Rodrigo Prieto, ASC, AMC.

Hoyte tells us that you also ‘tuned’ his anamorphic lenses.

Yes, we did optical and mechanical adjustments to his C Series [lenses] — which were first used on Interstellar [AC Dec. ’14] — to get close focus to about 2½ feet, and we customized the coating to make the flare more diffuse and reduce its blue component. We also built a custom 65mm lens for Hoyte that is very close focus.

Hoyte van Hoytema was invited to join the ASC in 2016.

You’ll find more of AC’s 007 coverage

from our archives here.