Spectral Strife: Shining Vale

Suki Medencevic, ASC, ASBiH, SAS collaborates with visual-effects supervisor Jason Piccioni to conjure the supernatural for the Starz horror-comedy series.

Images courtesy of Starz

The Victorian mansion that the Phelps family has just moved into has a tragic past, which may have left behind a ghost that’s now haunting the household’s matriarch. Or not.

The Starz series Shining Vale begins as Pat (Courteney Cox) — an erotic novelist who’s lost her creative spark — along with husband Terry (Greg Kinnear) and teenage kids Gaynor (Gus Birney) and Jake (Dylan Gage), uproot themselves from the big city in the aftermath of Pat’s romantic indiscretion. When the beleaguered mom is confronted by the ethereal Rosemary (Mira Sorvino), she’s at first horrified, but the two begin to form a bond as the ghost helps reinvigorate Pat’s writing, while sending her down a dark emotional path.

The audience is then left to wonder: Is Rosemary real? Or is she a figment of Pat’s imagination, fueled by recklessly prescribed meds?

The show is a rare hybrid of horror and saucy family dramedy, whose otherworldly visual effects are no Ghostbusters-scale onslaught of spirits, but often subtle and used to amplify or complete shots that could not be fully realized on set.

AC spoke with cinematographer Suki Medencevic, ASC, ASBiH, SAS and visual-effects supervisor Jason Piccioni about their collaboration on the show’s paranormal imagery.

Though the show’s lighting schemes aimed for the naturalistic, greater license was taken with Rosemary to re-mind the viewer that she is a ghost. The cinematographer lit Sorvino with unmotivated backlight (usually a Fresnel source) and introduced various colors in her key light. He and showrunner Jeff Astrof (who co-created the series with Sharon Horgan) agreed that the most overt touch would be adding a slight motion blur to her movement.

“I loved the script because you don’t often get the fusion of two genres at opposite ends of the spectrum in terms of style,” says Medencevic, who shot seven of the show’s eight episodes, which began with a pilot photographed by Nicole Hirsch Whitaker. “But what really caught my attention was the main character going more and more into a world of madness and possession — and as she does, the visuals could follow the same cues and expand upon them.”

Enter VFX supervisor Piccioni and his team at FuseFX, working predominantly in Foundry’s Nuke compositing and Autodesk’s Maya 3D-animation software. The visual-effects specialists added a light-latency effect so that bright parts of Rosemary’s image trail slightly as she moves. “For some shots in which Mira had little dialogue,” Piccioni says, Suki came up with the idea to shoot her at 24 fps, but then we would drop every other frame, step-print her, and composite her back in the shot — so she had some jitter to her in shocking moments when, say, Courteney turns around and sees her, and Mira moves and maybe talks a bit.”

Piccioni and his team also did substantial eye work on the female leads. At one point when Pat sits down to write, we get an extreme close-up of her pupil expanding dramatically, implying that either her meds are kicking in or Rosemary is possessing her. There are also moments where Rosemary’s eyes change color, hinting she might be a force worse than a ghost, and the same effect happens with Pat in later episodes, as she seems to become increasingly possessed.

“The effect started as a glow,” Piccioni says. “Golden when possessed, but not necessarily evil, and black when demonic. So much has been done with glowing eyes in sci-fi, and that was a tonal lane we didn’t want to get into — we wanted to stay in horror. Then we added an effect where the veins deepen in the skin [and] radiate out, which gets more intense as [Pat] grows more possessed and more evil.”

Piccioni would be on set for a couple of days per episode — less than usual due to Covid-19 protocols. Shots were mapped out, but that had to be done efficiently, as Medencevic was shooting Episodes 2 through 8 and had limited prep time. It was often a matter of Piccioni telling him what elements were required.

Regarding these elements, Medencevic offers an example of a “scene revealing Pat at the edge of the roof, which was shot as a greenscreen partial-build set, and the element of the attic had to [be added]. I shot the attic element from several angles, and [we] later VFX tiled the attic plate, which was composited into the final shot.

“For all VFX shots, I tracked information on lens focus, iris and any other technical data Jason might need,” the cinematographer continues. “We kept a very detailed log of camera and lens settings, and that data always accompanied the original footage. I was also present for the VFX spotting sessions, even for small things like removing a boom reflection or shadow.”

“We kept a very detailed log of camera and lens settings, and that data always accompanied the original footage.”

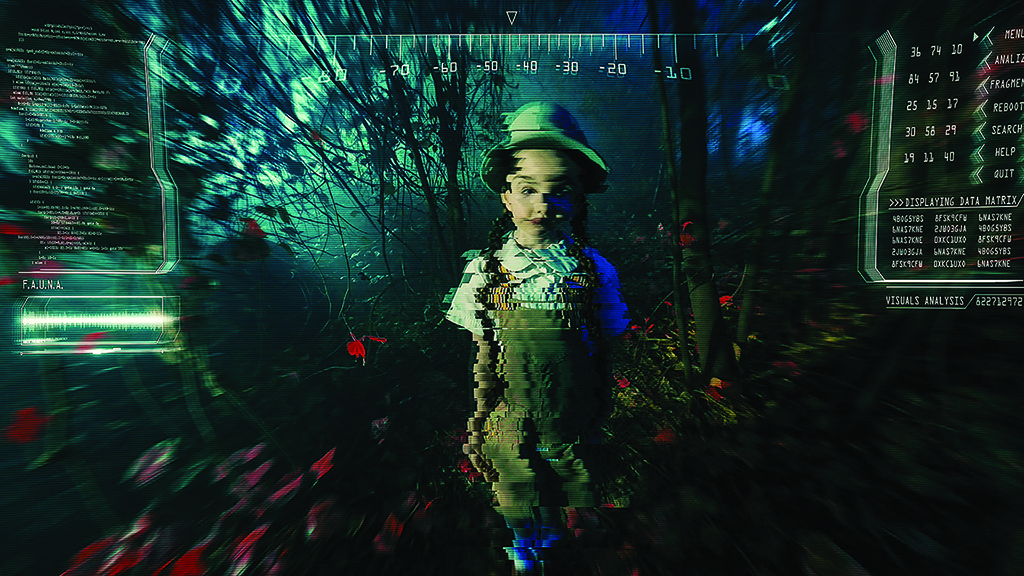

Though the primary camera for Medencevic’s episodes was the Sony Venice, there were several cases where other cameras were brought in to help achieve unusual looks. In Episode 3 (“The Yellow Wallpaper”), son Jake spends much of his time engaging with his AR headset — and gets a shock in a nearby forest when he’s greeted by Fauna (Lila Karp-Ziring), a digital character who takes an ominous turn — and who could pass for one of the twins in The Shining. (The show’s title is no coincidence.) Medencevic enlisted Sony’s a7 III camera for the task, specifically for its ability to help replicate the image within AR glasses.

“Using the Sony a7 gave us the mobility we needed to emulate the real POV of the person in motion. In addition, by using Sony still-camera lenses, we were able to get a very wide angle without adding to the weight and size of the camera.”

The crew shot the AR material as the sun went down. Medencevic’s team created a twilight effect with an 18K Fresnel and ½ CTO gel; the source was actually in the shot, but unnoticeable amid the shrubbery and atmospheric fog. With the ISO set at 12,000 or higher, the low light didn’t pose a problem for the a7 III. He shot at 30 fps to get a more “video” quality, and used the wide end of Sony’s FE 12-24mm f/2.8 zoom to create warping at the edges. Technicolor colorist Tom Forletta replaced greens with reds for an infrared emulation of an AR look before the material was handed over to VFX.

Piccioni reports that his team then “added a series of radial blurs that stretched out the image. [Lila] was shot in the forest and then rotoscoped, and given another color treatment, along with some time manipulation. Then we applied a glitch effect to her — inspired by [the video game] Resident Evil — that made her seem a little scarier, and added AR-display graphics at both ends of the image.

“The rotoscoping is just a way to isolate Lila, to allow us to treat her separately from the background so we wouldn’t lose her image as we messed around with the background filter effects. [The rotoscoping is] all manual — no bluescreen, as it would have inhibited our action in the woods.”

“The whole season had a lot of visual effects, and they always built on what we had already gotten in-camera and took it to the next level.”

While Shining Vale’s pilot was shot on location in a South Pasadena mansion, subsequent episodes were moved to the Warner Bros. lot. “They did a great job on the pilot, which just hints at where the story’s going,” Medencevic says about Shining Vale’s first episode, entitled “Welcome to Casa de Phelps,” shot by Nicole Hirsch Whitaker and directed by Dearbhla Walsh. “The pilot set up the foundation of the visual language in terms of camera angles, composition and some unusual moves. I spoke with Nicole prior to shooting and got her insight in terms of what they were going for and what I should build upon and continue throughout the season. It was a nice creative collaboration.”

The move to the studio tasked production designer Jeff Schoen with the formidable project of recreating the home’s spacious, distressed interior and front yard on three soundstages. Early on, Medencevic communicated to Schoen and showrunner Jeff Astrof that he considered it essential for all rooms to have ceilings, in order to maintain the verisimilitude of the pilot. The cinematographer then set out to prioritize what he calls “logical lighting,” with sources largely coming through windows or motivated by practicals — and occasionally breaking from this for dramatic effect.

He says the filmmakers (including episode directors Liz Friedlander, Catriona McKenzie and Alethea Jones) agreed that the kitchen should be “the warmest, brightest room in the house — the place that brings the family together. We wanted to communicate this in terms of lighting, color and composition. The other rooms would still be lit following the logic and motivation of the light, but the shadow areas would be more dominant in the image, keeping the mystery always present.”

The set was constructed for 360-degree shooting, with adjoining rooms providing layers of depth. Medencevic says lighting the multicolored stained-glass window up the staircase was the most challenging in terms of emulating the location’s look.

Testing with gaffer Ryan French and key grip Michael Pizzuto led to a setup that had an Arri T12 hanging from the rafters, which provided sunlight through the window. Meanwhile, a lineup of 2K Blondes was aimed into bleached muslin positioned behind the window — creating a bounce that provided a broad, soft source, which allowed the stained glass to register optimally.

“From above, I also lined up three 5K Fresnels with Chimeras that pushed a soft skylight onto the stage,” the cinematographer adds.

Strategically hidden key lights balanced the desire for motivated lighting with a pleasing look for the actors. Medencevic usually keyed with battery-operated 1'x1' or 2'x4' LiteGear LiteMat Series 2 bi-color LED units with RC4 Wireless dimmers.

In the more cramped tiki-bar set, he employed Astera Titan LED tubes in a way that didn’t overpower the overall naturalistic approach. “Lighting for the tiki-bar scenes had four different looks, depending on the scene and characters,” Medencevic says. “The idea was to always keep the lighting ‘invisible,’ and make it look like the set is lit only by the practical sources. The Astera Titan tubes augmented the look [created] by the practical sources, and provided nicer key light for the talent. In some scenes, mostly involving Pat and Rosemary, I would use these lights for theatrical effects — crossfading colors, introducing different color hues, stronger backlight, etc.”

Also assisting on the production was ASC member Steve Gainer, who served as 2nd-unit cinematographer on Episodes 7 and 8.

Medencevic shot primarily with Sony’s Venice in 4K raw format — having had a very positive experience with the camera and its 1,250- and 2,500-ISO capabilities while shooting the Amazon horror series Them (AC July ’21). “I somehow fell in love with the 1,250 ISO setting [which makes use of the camera’s internal NDs], since I would be able to very closely judge the look of the scene just by using my eye to light, and confirming it with the light meter,” he says. “The shooting stop will always be between 2.8 and 4. Only on some occasions would I switch to 2,500 ISO, and the difference would be very slight.

The cinematographer was tasked with achieving something close to the pilot’s anamorphic look, which had been realized with Arri’s Alexa Mini LF and Hawk’s Hawk65 Vintage’74 anamorphic lenses. “But I didn’t want to go with anamorphic because of its issues with close focus — especially because we were on a stage — and the range of lenses available,” Medencevic says. After testing many different lenses with the Venice, and evaluating the results with Astrof, they agreed on Hawk’s MiniHawk Hybrid primes.

“Their optical design produces an elongated bokeh and pseudo-anamorphic look while shooting spherical,” he continues. “The fall-off and lens flaring behave like Hawk anamorphics, except you’re dealing with lenses that can go anywhere from 2 feet to infinity, which would be very difficult with anamorphic.”

Wide focal lengths were favored, with the 35mm being the go-to. (Ed. note: The 35mm MiniHawk is actually a 17.5mm spherical with an ovular dual-iris. The lens mimics the angle of view and bokeh of a 35mm anamorphic.) “Wider lenses gave us more depth, which better connected the actors with the environment, keep-ing us aware of where we are and making the house a character in itself,” Medencevic says.

They kept wide even in close-ups — which had a distorting effect that’s used humorously when Terry gets drunk at the tiki bar with neighbor Laird (Parvesh Cheena), and frighteningly when a woman at a seniors’ home yells at volunteer Gaynor, warning the teenager to leave her haunted home.

Angénieux Optimo 15-40mm T2.6 lightweight zooms were employed for Steadicam work. “I am very familiar with the Angénieux zooms and I like the look they create,” the cinematographer says. “They are also very versatile and a good match with the MiniHawk lenses, which were used for the vast majority of the shoot.”

Medencevic estimates that he shot with two cameras — which is his preference — 90 percent of the time, and occasionally with three when lighting and blocking allowed. An efficient system was worked out whereby he would plan the shot with the director, who would then fine-tune blocking and angles with a camera opera-tor, while Medencevic attended to the lighting. “The system worked very well,” the cinematographer says. “It offered a chance for camera operators Josh [Turner] and Colby [Oliver] to contribute to the creative process in a larger way.”

In the same episode, Blackmagic Design’s Ursa Mini Pro 12K camera came into play for a bravura sequence. Medencevic chose this camera for its increased photosite count, which would allow the filmmakers plenty of resolution to create — in post — a 360-degree roll around the lens axis of the image. In the mansion’s basement tiki bar, Rosemary triggers Pat to fall off the wagon by pouring her a whiskey and ominously uttering, “Let’s get crazy!” A floating camera then manically pulls back up the stairs and through a closet, does a 360-degree lens-axis roll, exits the front door, and zips through the lightning-lit forest, coming to rest on a skull that morphs into a human face.

The rotation effect was a puzzling challenge, but director Catriona McKenzie insisted on it. “We discussed a number of ways that we could do this shot,” Medencevic says, “including using [an Arri] Trinity [camera stabilizer] and taking out walls and ceiling, but it was all very complex and we weren’t sure it would work. Finally, I realized that we could do it without actually spinning a camera at all! We could just spin the image in post — as long as we had enough image information. If you take a normal full-sensor image and you spin it, as it rotates you’ll see [the black portions beyond the edge] of the image. But if you push in on the image, you can rotate it without seeing the edges. This is why we needed 12K. I calculated that with the 12K sensor, I could zoom in, in post, to extract and rotate about 5.6K, which was more than we needed. So in VFX, we could get our spin without ever having to touch any special shooting gear.”

The sequence was captured in four sections. Medencevic shot the first section in the tiki bar, with operator Jake Avignone on Steadicam, and the last section in the forest, with Joshua Turner on a Technocrane. Medencevic additionally oversaw 2nd-unit cinematographer Itai Ne’eman, who shot the middle two sections — which were each captured in reverse — with Matthew Pearce on Steadicam. The camera was paired with a Hawk MiniHawk prime for the tiki-bar shot, and an Angénieux 17-80mm T2.2 for the Technocrane maneuver. A wide Arri/Zeiss Ultra Prime 10mm lens was employed for the 2nd-unit sections, in part to facilitate the cropping of the smaller image.

FuseFX stitched the four shots together to make it feel like one continuous move, which the VFX team further helped sell by speeding up the footage by a factor of seven to eight. Everyone was happy with the ambitious sequence — including Astrof, who had told Medencevic early on, “If this shot works, I can just retire.”

In Episode 4 (“So Much Blood”), Pat downs more whiskey shots at the tiki bar while talking to an unseen Rosemary. Blue light from LED LiteGear LiteRibbon recessed in the ceiling and under the bar provided ambient fill and a distinctive accent, as did vintage hanging practicals, a sconce and a table lamp. Pat is startled when an old 8mm film projector turns on by itself, revealing old footage of Rosemary trying to look happy at a birthday party. But the film jams on a close-up of her and creepily burns outward from her eyes.

Medencevic actually shot the home movie on an Arriflex 16SR3 Super 16 camera — paired with a Canon 8-64mm T2.4 zoom — at 16 fps, then had it transferred to 24 fps for a desired stuttering effect. He shot the footage on Kodak Vision3 500T 7219 stock, which was processed by Fotokem and scanned by Streamland Media.

“[Shooting with a 16mm camera] allowed us to have a video tap, which is really a key tool in today’s production,” he says. “I knew that I could shoot 16mm, but only frame the central portion the size of the 8mm gate. That way when we scanned [just] that [portion], we were truly getting 8mm film — although it was extracted from 16.” In order to frame for an 8mm aperture, he continues, “We created special ground glass that outlined our 8mm image on the full 16mm frame — basically cropping 50 percent of the image. We simply extracted the area of our ‘8mm’ image, which increased the grain and got it close to what it would look like if we had actually shot on 8mm. Then, VFX aged it and created a strobing effect, dirt and scratches.”

FuseFX animated the burning-film image — and, perhaps surprisingly, the running projector as well. “We wanted the projector to throw a lot of light, but running a film print blocked too much of it,” Piccioni says. “But if you don’t run film through the gate, then the reels don’t move and the whole thread doesn’t go. So, all those actions ended up being VFX.”

Whether a challenging shot was proposed by Medencevic or one of the show’s directors, the cinematographer would be tasked with devising the game plan, which often led him to call upon Piccioni and crew. “The whole season had a lot of visual effects, and they always built on what we had already gotten in-camera and took it to the next level,” Medencevic says. “On the camera side, we made sure to have all our elements ready, shoot it properly, and then give it over to Jason and his team — knowing they would make it all work.”

1.78:1

Cameras: Sony Venice, a7 III; Arri Alexa Mini LF (pilot only), Arriflex 16SR3;

Blackmagic Design Ursa Mini Pro 12K

Lenses: Hawk MiniHawk, Hawk65 Vintage’74 (pilot only) Vantage One4 (pilot only); Sony FE zoom; Arri/Zeiss Ultra Prime; Canon zoom; Angénieux zoom