Sphere and the Big Sky Camera

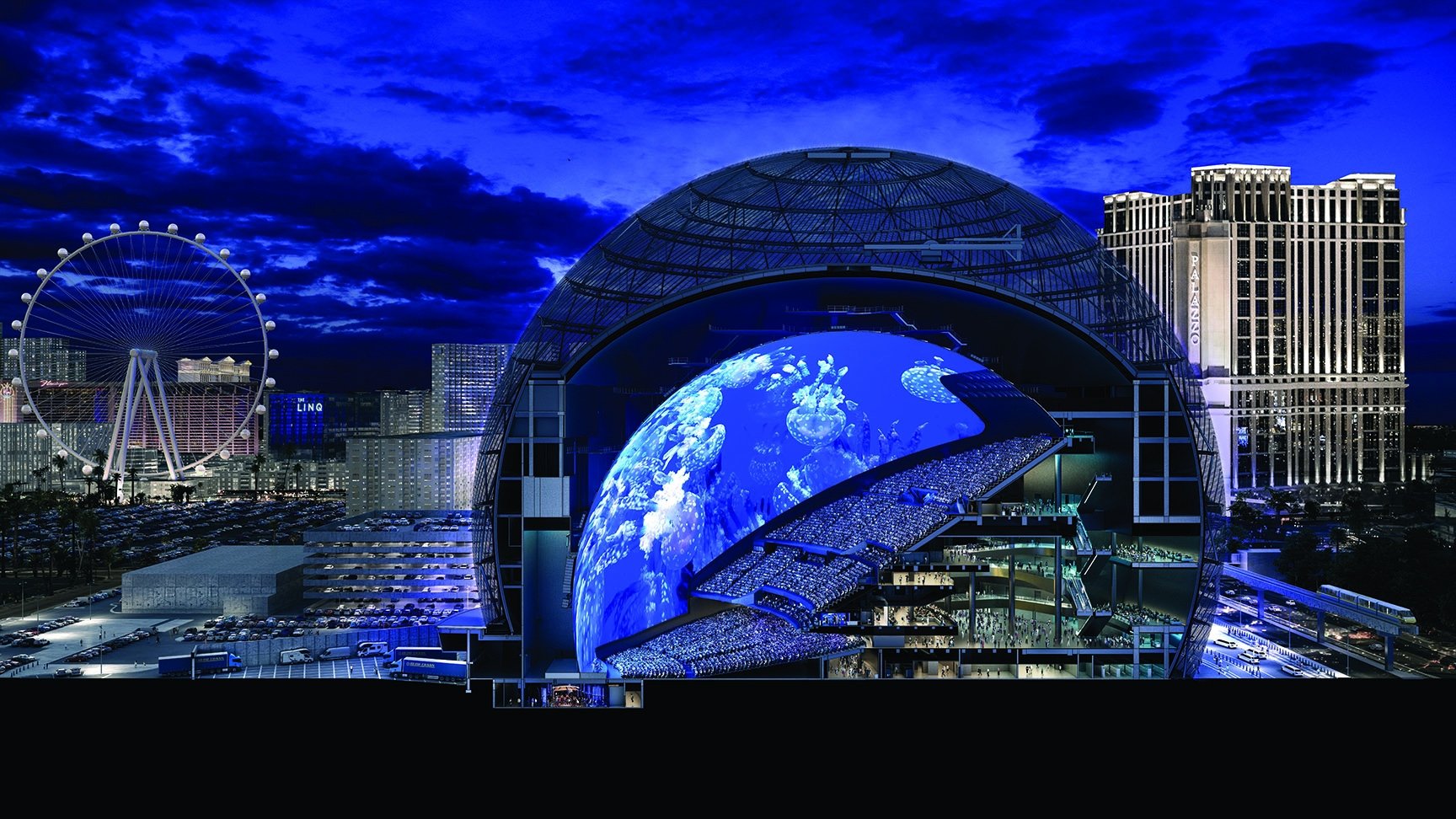

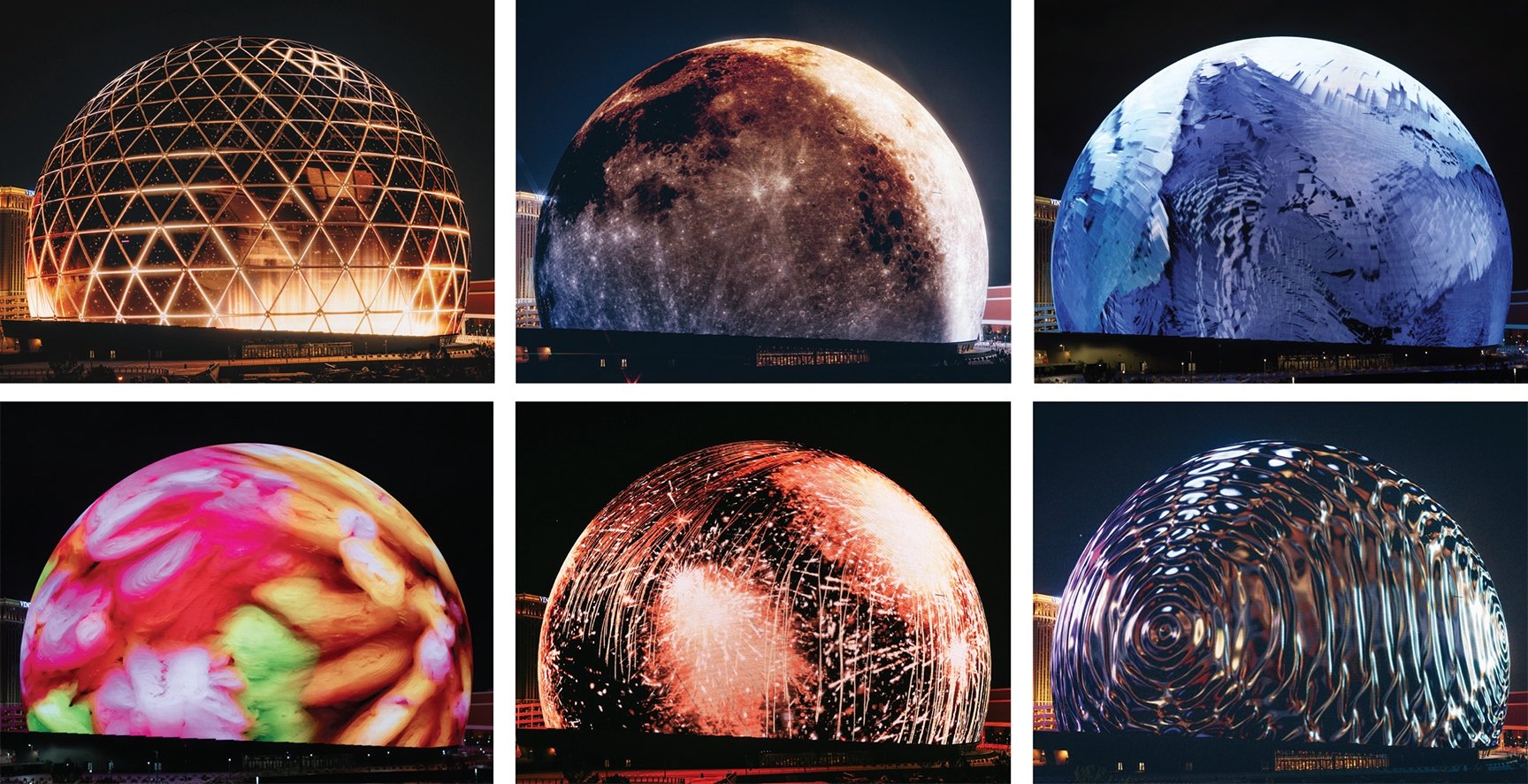

An eye-popping entertainment venue — and format — is unveiled in Las Vegas.

All photos and images courtesy of Sphere Entertainment Co.

Little in today’s production paradigm is truly groundbreaking, but Sphere in Las Vegas certainly is.

At first glance, this immersive entertainment venue suggests a modernized version of Disney’s venerable Circle-Vision 360, but, in fact, every stage of its production required bespoke designs custom-fabricated for just this application. And making it work required not only an unprecedented audio system, but a completely new capture platform built from the sensor up, a pair of nearly impossible lenses and an array of other new technologies.

The Specs

Sphere is a 516'-wide, 366'-tall geodesic dome that houses the world’s highest-resolution screen: a 160,000-square-foot LED wraparound that fills the peripheral vision for 17,600 spectators (20,000 if standing-room areas are included). The curved screen is a 9mm-pixel-pitch, sonically transparent surface of LED panels with 500-nit brightness that produce a high-dynamic-range experience. The audience sits 160' to 400' from the screen in theatrical seating, and the screen provides a 155-degree diagonal field of view and a more-than-140-degree vertical field of view. The image on the screen is 16K (16,384x16,384) driven by 25 synchronized 4K video servers.

Custom Camera

Sphere’s head of capture, cinematographer Andrew Shulkind, brought his extensive experience in alternative technologies — including virtual and augmented reality — to bear on the Sphere project. He notes that the endeavor “starts and ends” with Sphere Entertainment Co. executive chairman and CEO James Dolan’s vision of a “transformative experience” for audiences.

In assessing the venue’s ambitions and extensive camera testing, Shulkind redirected earlier efforts — which focused on multi-cam arrays, such as an 11-camera Red Monstro 8K array, a nine-camera time-lapse array and a nodal motion-control system — to a new custom single-camera, single-sensor concept that would become known as “Big Sky.”

Shulkind became involved with the project as a consultant, initially to help refine the technology and make it production-friendly. “We needed to make sure we weren’t building tools that we couldn’t use,” he says. “We had to be able to put the camera on a helicopter, on the end of a telescopic crane, or follow a race car on a track at 100 miles per hour. We needed to make sure that the tech wouldn’t limit the imaginations of the artists who wanted to use it.

“We knew we needed a single-camera solution, but there was nothing in the market even close to what we needed.”

“Shooting with arrays, which are commonly used for VFX plates and ride films, are too arduous to use as a primary system for Sphere,” Shulkind continues. “They’re too heavy to ship, too tough to rig, costly to stitch [the image in post], and they forced us to compromise too much on shooting in close proximity. We knew we needed a single-camera solution, but there was nothing in the market even close to what we needed.”

The only solution was to build the highest-resolution digital-cinema camera system ever created.

Building Big Sky

Enter Deanan DaSilva, a former CTO of Red Digital Cinema, whom Shulkind had known from earlier partnerships and had initially brought into the Sphere project to help innovate and solve myriad technical issues. After querying multiple camera manufacturers who were not interested in making such a custom product, DaSilva set about designing his own solution. The resulting Big Sky camera fea-tures an 18K sensor that measures 77.5mm x 75.6mm (3.05"x2.98"); the system is capable of capturing images at 120 fps and transfer-ring data at 60 gigabytes per second.

“I knew the sensor design came first,” says DaSilva. “Once we started the design, we realized that not only had no one ever built a sensor of this size for high speed, but no one had ever packaged one before. Honestly, we didn’t anticipate that issue, but due to the size and the heat, nothing traditional or pre-made would work. Everything had to be custom-created. We had to dive deep into the silicon pack-aging technology, how to dice it all up, wire bond off the sensor and hold it in place with ceramics and metals that were thermally matched. Once we had that functioning, we had to build the camera architecture around it — which, during Covid, was a challenge due to supply-chain shortages of materials. We had to figure out how to move 60 gigabytes of data from camera and onto media, which is why we decided to separate the camera and the record module — for now.”

The sensor is a 4.2-micron-pitch 18,024 x 17,592-photosite Bayer pattern. “Our dark photosites outside of the active sensor area total more than a 4K camera!” DaSilva says with a laugh.

“Our goal is to use this technology to take people to new places they haven’t been before and make them feel as if they had been.”

Unique Optics

The next task was to create a wide pair of lenses that would cover this new sensor and match the field of view of the screen. The curva-ture of the dome’s screen made a fisheye lens a natural fit. However, it would have to resolve extraordinary detail for the 16K pixel count of the screen.

An additional complication was that the audience’s natural vision inside the Sphere places the most important part of the image in the lower quarter of the screen; this is the most comfortable viewing angle, one that doesn’t require craning your neck to look up. There is still a considerable amount of image above the audience’s head, though — so, when a typical scene is shot, the camera must be con-stantly tilted at 55 degrees to capture an angle of view that fills the entire screen, with the “center” of the action framed through the lower edge of the lens.

However, the actual center of the lens is where any lens delivers the best optical performance. This is especially true of fisheye lenses, whose periphery often yields an image quality lovingly described by professionals as “mush.”

For Sphere, the team had to create a 165-degree-horizontal-angle-of-view fisheye lens with an edge-to-edge performance exceeding 60-percent MTF at 100 line-pairs — an extraordinary feat for any photographic lens. The result is a lens the size of a dinner plate, reminiscent of the Todd-AO Bug Eye or the Nikkor 6mm, but with astounding sharpness and contrast reproduction right to the extreme edges of the angle of view. And there is almost no chromatic aberration in the image, even to those extreme edges.

“The lens is reasonably fast at f/3.5,” notes DaSilva. “It’s actually optimized for f/4.5, and that’s where it performs best, but we al-lowed it to open up a bit more. The precision of polishing for this lens is in the subwavelength range across the curvature, and we had to develop an entirely new process for precisely moving the focusing groups. We also had to utilize advanced variable vacuum-depositing processes to adhere the anti-reflection coatings onto the very aggressively curved elements.”

Custom Lens Mounts

The 3", nearly square sensor also required a proprietary new lens mount for the optics — which, fortunately, has a relatively shallow flange depth. (This makes the optical design just a bit easier to achieve.) A second 150-degree fisheye lens was quickly put into production, and DaSilva set about collecting medium- and large-format still lenses that might cover the sensor appropriately. In fact, his buy-ing spree on eBay sparked a number of price hikes in the lens market.

“Deanan would buy one lens and then turn around a couple weeks later to get another copy, only to find that it had nearly doubled in cost!” Shulkind notes, laughing. “He was basically driving the cost up for himself!”

A series of lens-mount adapters was crafted to mix existing glass with the Big Sky lenses for Sphere’s first narrative project, Postcard from Earth, directed by Darren Aronofsky and photographed by Shulkind in 26 countries around the world. (Matthew Libatique, ASC also contributed by photographing an eight-minute narrative that bookends the film.)

“For movies, 4K is good enough. With Sphere, good enough isn’t good enough anymore.”

Immersive Operating

As with everything related to the Big Sky, even composing images and operating the camera is a unique experience. There are no existing monitors to approximate its huge image, or screens that can demonstrate its wide field of view, so the in-house team created a series of playback tools, including a custom VR headset application that “projects” the camera’s view onto a virtual Sphere dome screen; the operator can “sit” anywhere in the theater and anticipate exactly how the shot will be experienced by the audience.

Custom Sound

The Sphere Immersive Sound system, developed in partnership with the German company Holoplot, involves 167,000 speakers that direct sound to the audience like a laser beam — and with nearly the same precision. The system not only delivers delay-free and echo-free sound to all seats, but it can also create wholly immersive 3D audio by placing a sound in any position in 3D space.

Further, the system can deliver an entirely different soundtrack, in various languages, to different positions in the theater. So, within a small group of seats, one viewer can listen to a French soundtrack while the neighboring viewer hears English — both in perfect sync with the picture.

Custom Workflow

The Sphere team is blurring boundaries between prep, production and post to deliver a 16Kx16K image on the screen. That includes un-compressed recording, off-board image processing, custom recording media and some elegant solutions for how to manage media. The standard frame rate for Big Sky is 60 fps, and new software had to be developed just to move the footage, check the footage, create dailies and deliver images to the venue.

“We started with getting ‘dailies’ about two weeks out,” DaSilva wryly recalls. “Then we got that down to one week, and then to a day. By the time Darren was shooting Postcard, we had the system refined so that he could look at his footage, fully processed in our Big Dome test theater in Burbank, Calif., in just one hour.”

The Big Sky 32-terabyte media magazines can record 17 minutes of uncompressed footage of up to 60 fps, an achievement aided by the system’s 30-GB/s transfer rate. The recorders can also record with two magazines — simultaneously for 120 fps, sequentially for extended recording times, or for offloading to 96-TB transfer magazines.

Once footage is offloaded, SphereLab software is used for processing dailies, performing one-light color passes, exporting full-resolution EXRs, or outputting directly mapped (carved) imagery for Sphere screens. On location, laptops paired to a Big Sky recorder are typically used to offload, one-light color and generate dailies.

What Lies Ahead

Sphere currently has 10 Big Sky cameras, and there are more coming. Also in the works are a lighter body, a smaller lens and an updated underwater housing, among other innovations. The Sphere team has also partnered with NASA and the ISS National Lab to send a Big Sky camera to the International Space Station. More Sphere venues are in the planning phases for other international locations.

“Over the last 20 years or so, advances in cinematography have given us the tools to work at higher thresholds than we ever deliver,” Shulkind observes. “We’re shooting with 8K cameras to deliver 4K movies, and we’re working with lighting, exposure and color fidelity far beyond what we can actually display. Now, with Sphere, we’re actually able to maximize and push these technologies further in the service of something convincingly real, which wasn’t the goal of moviemaking. Our goal is to use this technology to take people to new places they haven’t been before and make them feel as if they had been,” Shulkind concludes. “For movies, 4K is good enough. With Sphere, good enough isn’t good enough anymore.”

You'll find our look at the hyper-immersive Sphere concert experience U2:UV Achtung Baby Live right here. You'll find more about the sci-fi experience Postcard from Earth here.