Postcard from Earth at the Sphere in Las Vegas

Personal notes on viewing director Darren Aronofsky’s experimental sci-fi experience.

All photos courtesy of Sphere Entertainment

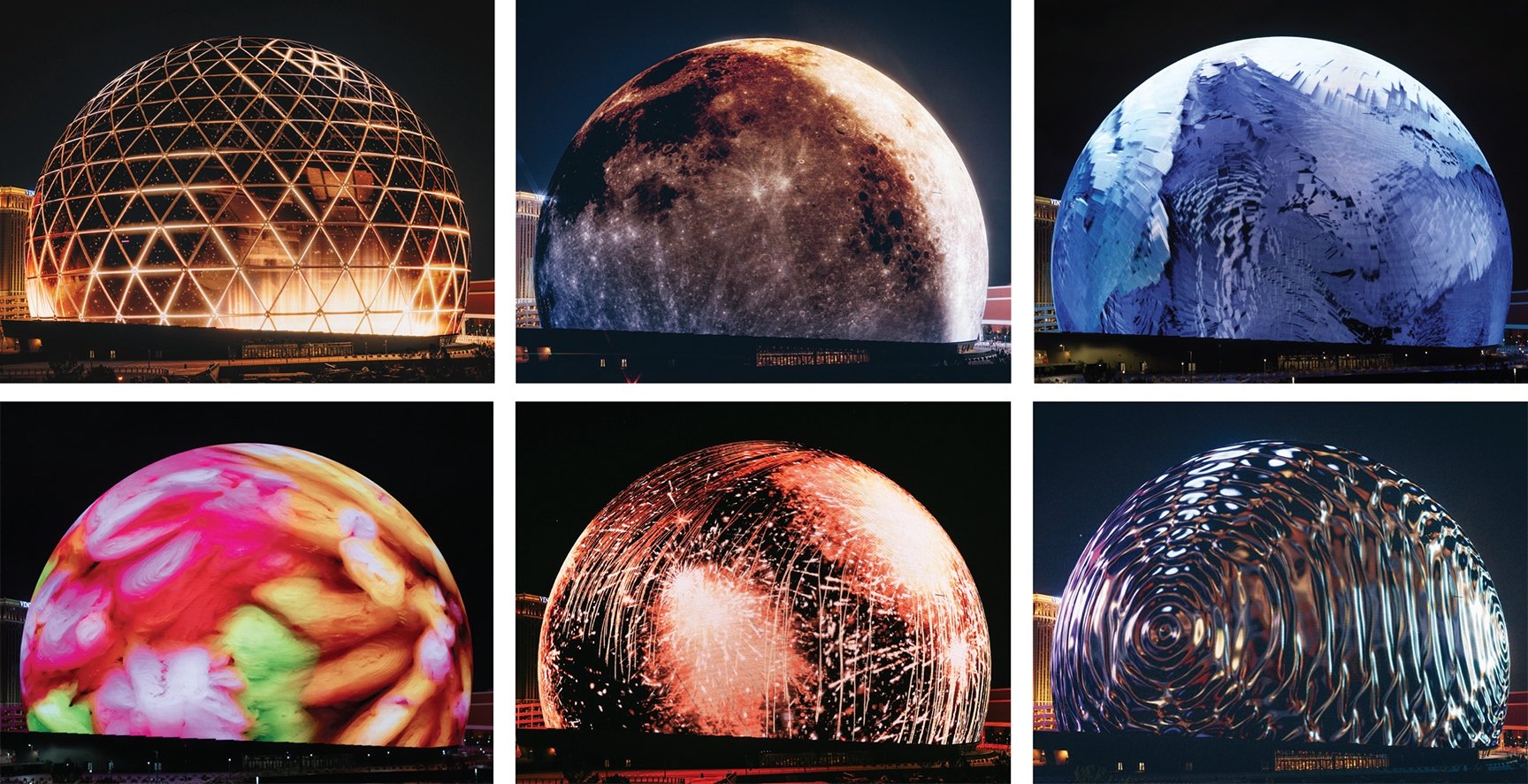

Riding in our taxi through the streets of Las Vegas, my wife and I caught sight of the Sphere in the distance, and it felt a bit diminutive. The swirling pattern of the Exosphere morphed into an ad for, I believe, a boxing match — it was hard to see from our perspective. But as we got closer, the size and scale of the Sphere became much clearer; it’s gargantuan. So much so that the over 1.2 million 48-pixel LED ‘pucks’ that make up the Exosphere are a bit dizzying to look at from the entry plaza.

Once we walked into the facility, the maze of escalators and cool-colored, glowing décor met us with the feeling that we were inside some sci-fi movie. The design evokes an experience of being in a theme park with food and drink vendors and central technology displays. A large simulated holographic display shows abstract dancing patterns hanging over the main atrium and, for the opening night, the atrium had three stations with AI-driven robots who greeted guests and held light conversation with them, offering vaudeville-like jokes and even some signing to the mixed amazement and creepiness of the spectators. Some were transfixed, some were seriously creeped out and nearly ran from the robots. Another area of the main floor has an interactive demonstration of the immersive sound system and its ability to target various soundtracks to different members of the audience. Intermixed with the future-flung theme park, the facility is something of a mix of an ultramodern transit station, with cool LED blue light everywhere amid clean lines of black and metal.

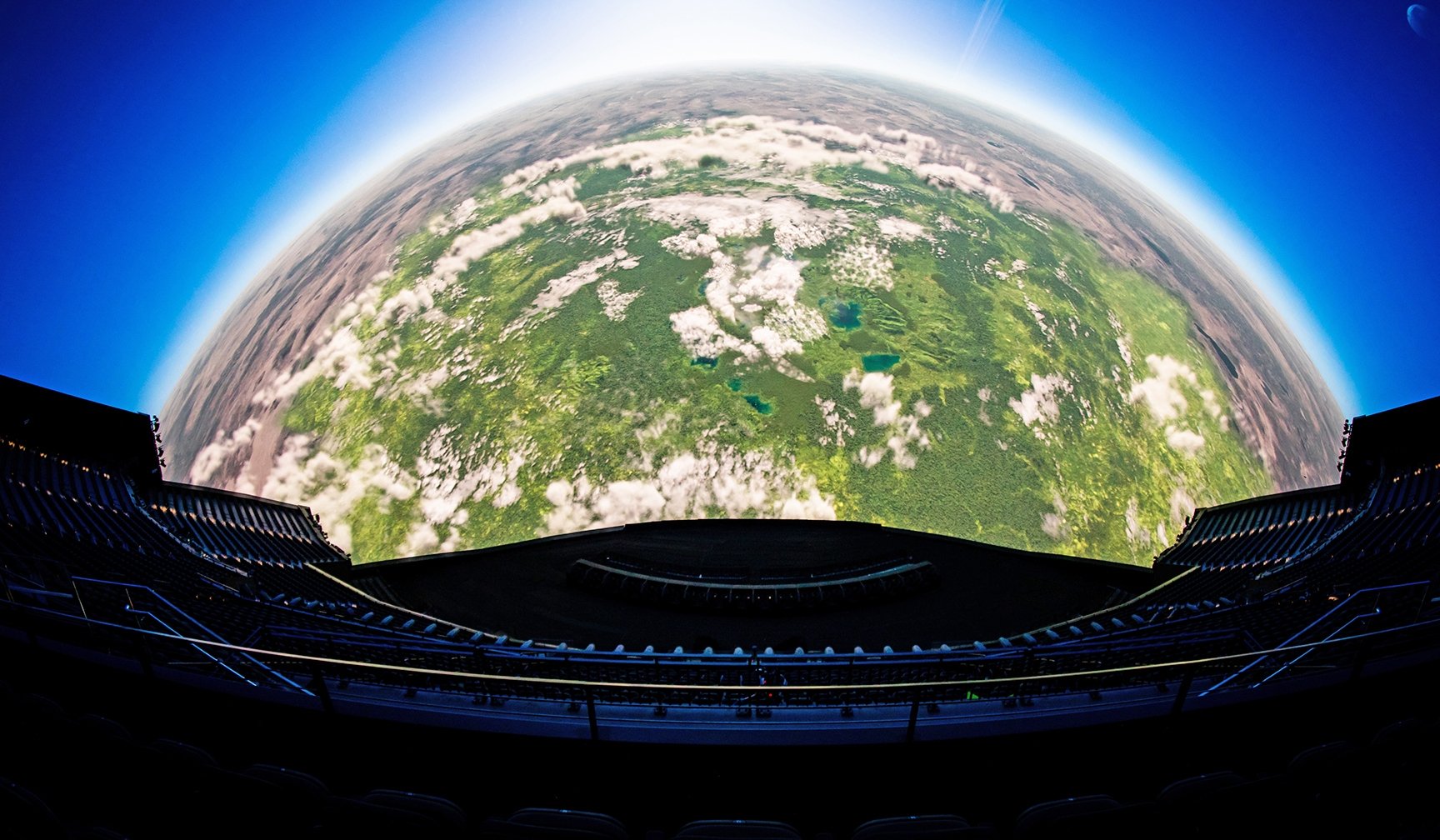

We rode up the escalator to our seating level and walked through double doors into an antechamber and through the doors leading into the main auditorium. Passing through the walkway into the auditorium is a bit akin to walking in a sporting arena between the bleachers, and when you step out into the theater — it feels like a sports stadium. The aggressively raked seats, the multi tiers and the vast expanse of the Sphere is difficult to describe. With 17,600 seats, it feels like you’re in half a football stadium with the other half being a gigantic, curved wall that completely encloses you in the Sphere.

Cleverly, the filmmakers decided to put a white rectangle on the screen that had a subtle abstract pattern in it with even more subtle changing colors. This small rectangle, only 10% or less of the screen, was about the size of a normal theatrical screen. Taking our seats, there was an excited hum in the venue as the audience of nearly 5,000 settled in. While the venue is capable of up to 20,000 people, for presentations that utilize the entire Sphere screen, there are limitations of seats that are viable with full unobstructed view and those top out at about 5,000. For example, there’s a second-tier balcony that extends nearly completely over the first floor’s seats making it impossible for them to see the top of the Sphere’s screen. For live concert events — such as the U2 residency — the venue can fill to capacity and utilize the screen as additional visual entertainment along with the performance.

“The camera was incredibly difficult to work with. It’s basically shooting in all directions simultaneously. A piece of dust on the lens becomes the size of a football on the screen.”

— Darren Aronofsky

Filmmaker Darren Aronofsky led off the evening, introduced by producer Jane Rosenthal, and he humbly welcomed the crowd. He acknowledged that this would be the largest crowd he’d ever seen one of his films with. When Rosenthal first started speaking, it was difficult to find her in the massive theater. Just about the time she handed the microphone to Aronofsky, my wife and I finally spotted them in corner of the level below us. Even in a spotlight, they were only ant-sized and merely abstract figures in the huge venue.

The film Postcard from Earth begins with a spaceship. It plays within the small rectangle on the massive screen as a short bookend narrative about two humans who have been sent away from Earth to a new, uninhabited planet, to prepare it for more humans. We have all left Earth, our home, to seek out other places for humans to thrive and allow the Blue Planet to heal from our scars. The astronauts — played by Brandon Santana and Zaya — awake from deep hypersleep to soft voices who lull them to consciousness with not only gentle instructions, but also a story of where they came from. This includes a brief history of Earth and, eventually, why humans left this glorious rock in the Milky Way.

“It’s not film, it’s more of an experiential medium; trying to convince people that they’re not in Vegas, they’re experiencing what they’re seeing.”

As this tale is told to the astronauts, and we see them waking from their deep slumber — in a sequence photographed by longtime Aronofsky collaborator, Matthew Libatique, ASC, LPS — we are greeted with a view of our planet as seen from space. As the image moves in closer, the planet grows until it breaks the rectangular theatrical aspect ratio bounds and grows to fill the entire Sphere screen. The audience could not help loudly verbalizing their impressions as the massive planet suddenly engulfed our view. The film then goes on to show extraordinary natural vistas as we float above them in a gentle glide. This delicate hand is so important with this format as the huge screen quickly imparts feelings of motion on the audience.

I had the pleasure of speaking with Aronofsky via Zoom just after the premiere weekend and the director noted, “It’s not just a movie, it’s kind of an amusement park ride. A new exciting medium to explore in. We were very concerned, early on, about what kinds of moves we could do with the camera that would be tolerable for the audience; what types of moves don’t create nauseousness in the audience. We had some theories on movement, pushing and pulling or rising or sinking are good moves, but panning left and right could easily induce queasiness. The original demo reel had tons of roller-coaster type shots in it, but I didn’t want to do that, I wanted to do something in a classy cinematic way, and I certainly didn’t want thousands of people retching!”

Indeed, one moment of the camera coming to a cliff’s edge and then tilting forward and dropping — ever so gently — over the edge induced a clear feeling of vertigo and a vocalization from the whole audience, but Aronofsky refrained greatly from those stunts. The film ventures from a desolate planet to human inhabitants and travels on multiple continents to see these humans in their natural habitat – many exotic and beautiful locations. The venue kicks things up a notch with wind generation machines so that as the camera soars through the ice-capped mountains, you actually feel the wind in your face and the cold. Furthermore, scent machines bring alive the aromas of a citrus field as we watch migrant farmers reap their rewards.

Additionally, with more than 160,000 speakers in the venue, the sound is impressive. Not just the volume, but the directionality and specificity of it.

“I have experience in VR and how you direct a viewer to look in certain spaces,” Aronofsky noted. “It’s funny, with this huge screen that wraps around the audience, I watch people looking straight ahead just at the center portion. That’s what we’re used to doing, right? We sit in our seats at the movies and concentrate on what is right in front of us. So, we had to encourage people to look around a bit more; to experience the full environment.”

The director inspired this visual exploration through the positioning of sound. By taking the voiceover and directing it to come from different areas in the Sphere, he encouraged the audience to turn their heads and look up and down and follow the actor’s voices — in a very gentle and natural way.

One of the most memorable moments in the film, Aronofsky cuts to a black-tie audience sitting in a beautiful vintage opera house staring directly at the Sphere audience. He holds on this shot for an oddly long time, eliciting nervous titters from the Sphere’s audience as they look directly into the eyes of people who are 100' tall — just staring back at us. The experience is odd, unsettling and also very intimate. This cuts to a single violinist on stage — the actual object of the vintage theater’s gaze — and as she begins to play the clarity of the instrument’s sound is transcendental.

“Talking to my composer about the score, he noted that the sound of a single violin in a place like that with 160,000 speakers, you’d hear the sound of strings and breathing all at once,” Aronofsky described. “I thought, we should do a shot of that! And then came the idea of a theater thing where everyone looks at the camera and I thought it was a really cool moment.”

One further 4D touch of the Sphere venue are the haptics in the seating. With the explosions of the spaceship rockets at the beginning of the film, our seats vibrated aggressively to emulate the seismic reverberations of the escaping spacecraft. While that was fun, I truly loved the experience of a sequence later in the film as we cut to riding in the backseat of various taxicabs around the world. In this case, the subtle haptics interacted precisely with the various roadways, feeling the exact sensation of being in that backseat, from the bumps of the expansion joints in a bridge as the taxi drove over it, to the vibration of the engine. The sensation was extremely real coupled with the immersive image and sound.

Putting this all together wasn’t without its incredible growing pains. As detailed in my previous AC feature on the Sphere, the technology required for the camera, lens and postproduction was all created custom from scratch exclusively for this venue. In our conversation, the director discussed these challenges.

“The camera was incredibly difficult to work with,” Aronofsky notes. “It’s basically shooting in all directions simultaneously. A piece of dust on the lens becomes the size of a football on the screen. Getting the image we wanted took about a dozen people to turn the camera on and capture the information pouring out of it. And when we started, the Big Sky camera didn’t even exist yet, it had to be built. We were working with a multi-camera array and then stitching multiple Red camera images together. It was very hard. No one had ever done any of this before and we didn’t even know how we were going to do this. How would we glue the image together in the Avid, how would that translate to the Sphere. Then we had no idea how we would mix the sound for 160,000 speakers and they hadn’t considered that the only way to do that was to mix inside the actual Sphere. We had to invent the technology to do that. There was so much that we did, initially, that was totally blind. We really had no idea how it would translate to the Sphere at all until just a couple months before the premiere.

“It’s a different medium,” the director concludes. “It’s not film, it’s more of an experiential medium; trying to convince people that they’re not in Vegas, they’re experiencing what they’re seeing. It’s nice to be with that many people watching a movie together — thousands of people pointing and shrieking and seeing things anew simultaneously. I didn’t know that jaw dropping was a real thing until I saw it actually happen to 5,000 people all at once! That was pretty spectacular.”

Indeed, the energy of the audience was palpable as they filed out of the venue. Sphere’s first exploration into this new format was a hit and I, for one, look forward to the creativity of many more filmmakers exploiting the extravagance of this medium to tell wholly new stories and experiences.