Visual Effects for Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom

“It’s funny, but a lot of times you don’t know what the hard shots are going to be and other times you know right from the start.”

This piece originally ran in AC, July 1984.

Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom is an apotheosis of all the Saturday matinee serials and action melodramas of the Thirties and Forties. It is delightfully eclectic in its appreciation of ideas too long neglected, which are recreated with the advantages of more time, money, personnel, sophisticated equipment and accumulated knowledge than the pioneers of the adventure film could have dreamed of. Even as it harks back for inspiration, it is innovative moviemaking — the Citizen Kane of adventure epics.

It begins with a flashy nightclub act in which “Anything Goes” is rendered by a dazzling blonde, Kate Capshaw, and chorus girls in the best MGM musical style — but since the setting is Hong Kong, the lyrics are Chinese. Harrison Ford is then poisoned by the gangsters he’s dealing with (DOA, 1949) and, after a struggle to retrieve the antidote, escapes with Kate after a long fall through the awnings of a high building (Pirate Treasure, 1934).

Following a harrowing auto chase (Bullitt, 1968), Ford, Capshaw and a juvenile Chinese taxi driver, played by Ke Huy Quan, with the mob at their heels, make their getaway in an airplane piloted by mysterious-looking Orientals (Lost Horizon, 1937). The pilots, employees of the gang chief, open the fuel petcocks and bail out, leaving the passengers to crash in the mountains (Drums of Fu Manchu, 1940). Lacking parachutes, they bail out in an inflated life raft, sliding down a mountainside and over a precipice into a deep river gorge (we could recall no precedent for this!) Ford, the girl in the dance costume, and the youngster find their way to a remote Indian village (Tarzan’s Desert Mystery, 1943), whose inhabitants are bereaved because evil cultists have stolen a sacred relic from their village (Tarzan and the Amazons, 1945) and kidnapped their young sons.

Going through the jungle toward the temple of the enemy, the trio is menaced by hordes of giant vampire bats (Jaws of the Jungle, 1935). At the temple they are entertained at a pagan feast (Lives of a Bengal Lancer, 1935). That night, they enter a secret passage filled with insects and are decoyed into a room in which a spiked ceiling descends toward them (Call of the Savage, 1935). Escaping, they find their way to a secret Kali temple where they watch a horrid Thuggee ritual and are captured (Gunga Din, 1939). The girl is being lowered into a lava pit as a sacrifice (Tiger Woman, 1944) when Ford swings down on a rope and rescues her (The Hunchback of Notre Dame, 1939) and they flee into subterranean mines worked by the kidnapped slaves (Darkest Africa, 1936). Ford and friends lead a revolt of the slaves (Buck Rogers, 1939) and are chased by Thugs in mining carts (The Vigilantes are Coming, 1936). The High Priest floods the mine and they are pursued by a wall of water (Daredevils of the Red Circle, 1939), which finally bursts out through the face of a precipice (Jungle Girl, 1941). They reach a rope bridge spanning a deep chasm over a crocodile-infested river. Trapped, Ford cuts the bridge and the thugs fall to the saurians (Tarzan’s Revenge, 1937). Clinging to the broken bridge, Ford fights the High Priest, who is followed down by the camera as he falls to his death (She, 1933).

Need it be said that Lucasfilm’s famed special effects facility, Industrial Light and Magic (ILM), played a vital part in putting this old-fashioned yet newfangled extravaganza onto the screen? The burden of seeing it through landed upon the shoulders of visual effects supervisor Dennis Muren, four-time Academy Award winner who was an important contributor to the success of The Empire Strikes Back, Return of the Jedi, Dragonslayer and E.T. - The Extra-Terrestrial. A remarkable cadre of artists and technicians worked long and hard to bring the visual effects to life.

“Our first shot in the picture,” Muren recalled, “is the closeup of Indiana Jones and the girl hanging on the awning. They weren’t actually in Hong Kong when that scene was shot and we did a bluescreen composite here. The interiors of the cars during the chase were done here. Allen Daviau [ASC] shot that and our stage crew set it up. Joe Johnston worked on the design. We did it all in ‘poor man’s process’, where instead of using mattes or rear projection we rely on more old-fashioned effects, taking advantage of the limited depth of field when shooting with the lens practically wide open. With the backgrounds being out of focus we can get a prettier shot that you can pan and tilt on and it doesn’t look like an effects shot. We had spinning lights around the sides that were rotating like giant merry-go-rounds so the light patterns were changing, and overhead lights rigged so they would cause moving reflections on the windshield.”

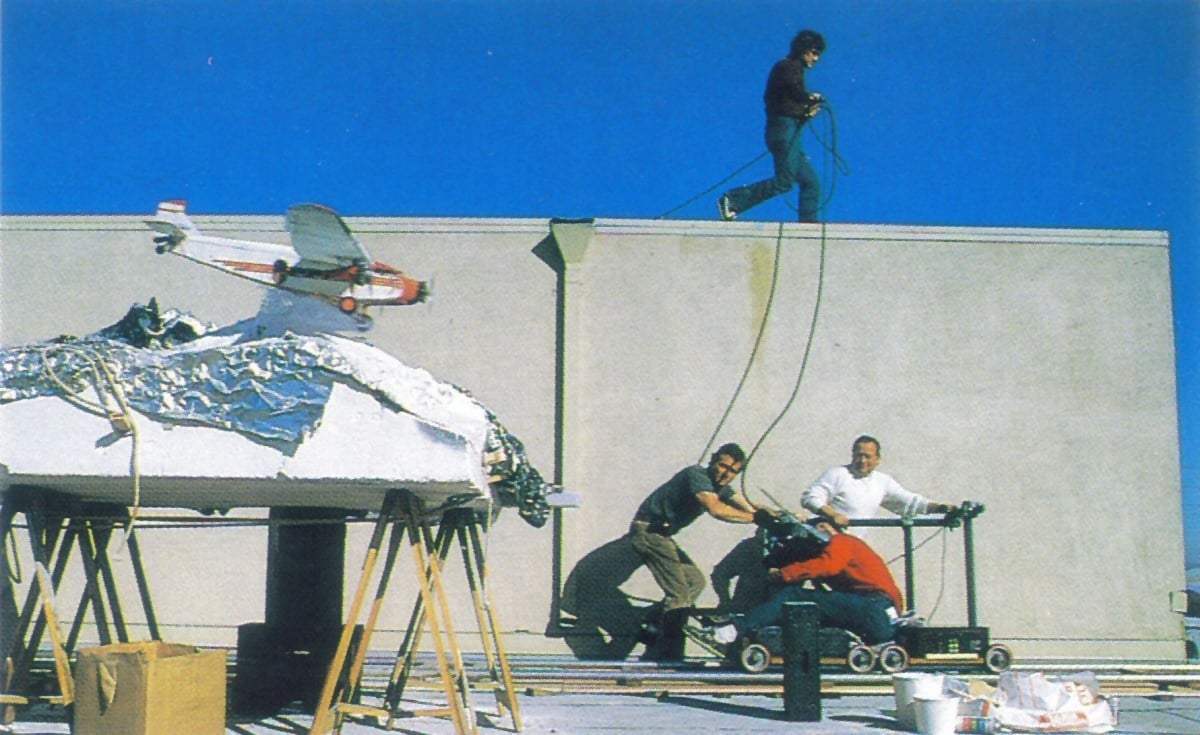

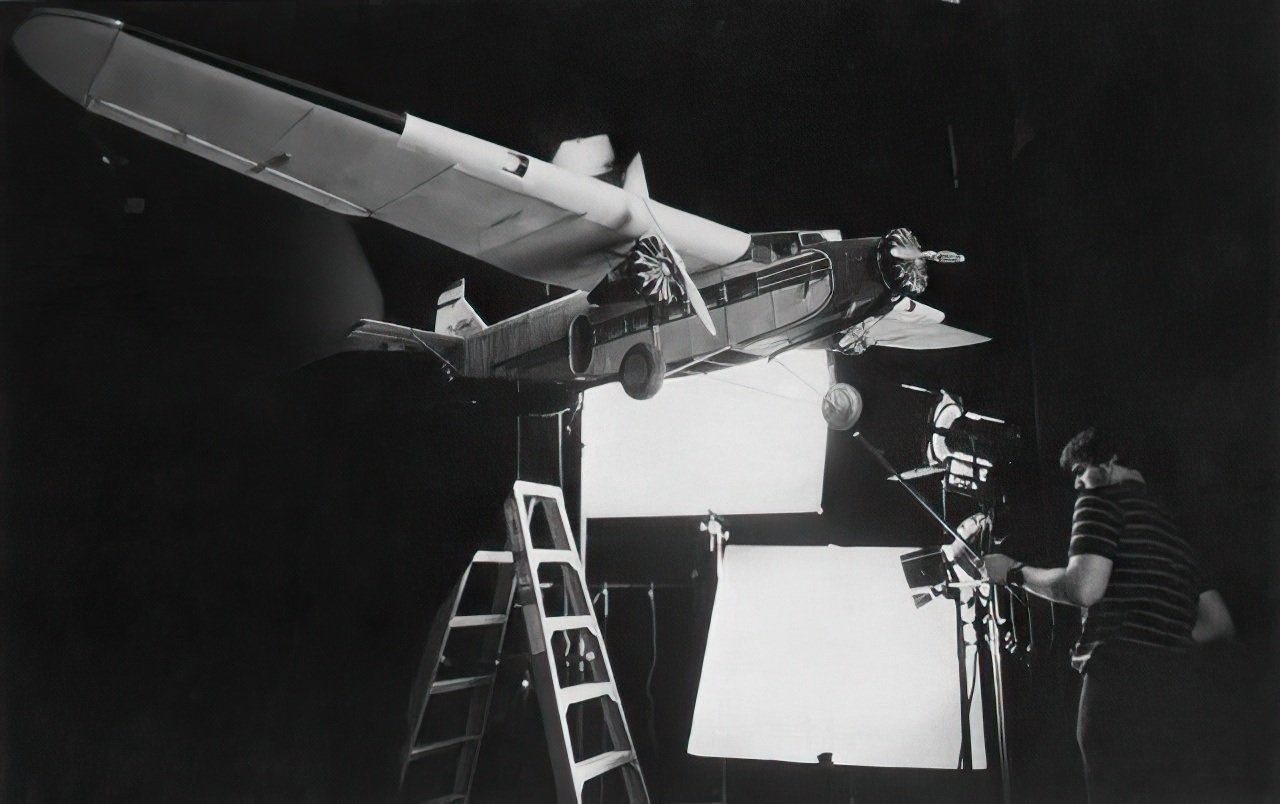

Some of the scenes involving the Tri-motor plane were filmed with models and intercut with actual aerial footage photographed by Jack Cooperman, ASC. The models were built by Michael Fulmer and Ira Keeler with wingspans of about four feet. “The shot of the plane wheels hitting the mountaintop was done as a trucking shot as though we were shooting it from another airplane,” Muren said. “We actually dollied along and shot it on our rooftop and painted the wires out. We were shaking the camera around to make it look like a tough shot. The cockpit shots, where they see mountaintops approaching, were bluescreen shots. We first did the shot where the plane crashed into the mountainside and the raft is coming down in the foreground without having it explode, as it was supposed to be out of gas. But it just didn’t look right so we added the explosion later. We have since found out that when a plane runs out of gas, there’s so much vapor left that they do blow up.

“The raft coming down in that scene was shot at Mammoth Mountain, where the background plates were made. We did a lot of what we call pre-comps on those because the VistaVision negative is bigger than the Panavision we extract from it and we have 40 percent unused room at the top and bottom of the frame only. We did our compositing in VistaVision and diffused it slightly to get rid of the grain; then when we reduced it down we used the additional area at the top and bottom to add more shake to the composite. We did the same thing with the mine chase sequence because any cameraman out there shooting this stuff is not going to be as disciplined and controlled as when you have a fixed, locked-off camera. For the crash, we made a smaller model about two feet long out of balsa wood and paper on a model set about 25 feet long. We did that in two cuts; we slid the plane down wires for when it hits the mountain, then jump cut immediately to the plane on the end of a rod sticking out of the mountain pulling it into the mountain so we could get the force of the wings breaking off and the pieces flying all over. Then we put the explosion over it.

“We have about five bluescreen shots following that, where the people are in the raft being shaken about to add the same rough feeling to it. When they slide down and go off the cliff, that was a real cliff and a real raft shot in Idaho by Frank Marshall. We replaced the top part of the cliff with a painting and rotoscoped the raft in front of the painting for the first few frames. We didn’t use full-frame projection because it tends to look grainy, the color is off and the contrast range is so different. Anytime ILM does any work that requires a full-frame duplication of an image we’ve been doing it optically and not with projection.

“The next thing we did was the castle off in the distance, which was a matte painting, with the elephants going toward it. We had another matte painting where they’re closer to the castle, which was painted by Mike Pangrazio. It was matted directly into the background using the real sky. Elliot Scott, the production designer in England, had set that shot up. He started out with Thief of Bagdad, so he knows all about effects, and I said, ‘Great, it couldn’t be any better,’ so I set the camera up that way and shot it. Then we found we had to add bats to the shot. We started looking for bats, but it was the wrong time of the year in the Western Hemisphere and they were all in hibernation. I looked at the bat footage they had done with the large bats in Sri Lanka and these bats flew in formation, more like birds, so we shot seagulls at a dump near Petaluma and a lot of starlings at Fairfield. We shot them two stops underexposed against the sky and pulled a matte off them. The view of the walk to the temple in the red-lit chasm is a combination of painting and model with bluescreened people, using doubles.

“The temple was an incredible Elliot Scott set in England. Joe Johnston went over there and supervised the shooting of the plates. What they didn’t have was the bottom of that pit which separates the native people from the ceremony area. We added to that bubbling lava with steam and fire coming up. We didn’t want it to look like passive or flowing lava, so we had a lot of surging and boiling to keep it active. The miniature was quite elaborate and it took some very difficult optical compositing to get rid of the edge of our miniature set. Their pit was only 10 feet deep with probably a half-dozen arc lights in it and a dozen 10Ks.”

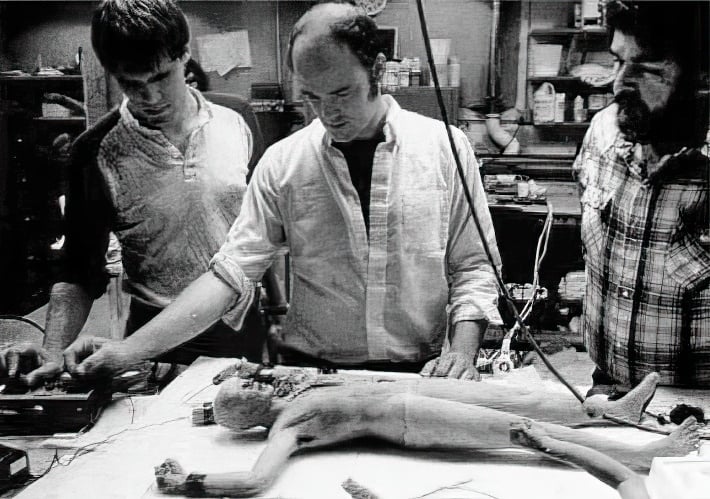

There follows a scene that has aroused the ire of some of the more sensitive critics: the villainous high priest thrusts his hand into the chest of a sacrificial victim and plucks out his heart, which continues to beat as the gaping wound closes and heals. “David Sosalla made a rubber chest-piece of the actor with a ribcage structure inside,’ Muren explained. “It was pre-broken on the inside so we could actually put a hand through. We kept it very dark so it wouldn’t be too graphic because we wanted it to be more of an idea of what’s happening than something you’re seeing. The closing piece was done in reverse with enough internal structure to look like the rib cage inside. We actually pulled it apart, but in reverse, it went back together again.

“After that came one of the hardest sequences, the people being lowered into the pit. The original budget had both of these scenes done with the camera looking down at the people being lowered, and looking up at them coming down toward the camera, which would have been really difficult to do to show their faces. I was thinking of going into some sort of projection thing with the faces, but, fortunately, Steven came up with the idea of building a quick set and the up-views over there with the real actors. He ended up doing all the up shots and we did the down shots. He put a lot of smoke into these scenes, so we had to have it in ours. I decided to do the whole thing as if it were real and build a big model for the thing. Originally we had planned to do the figures 30 inches long, big enough for the details to show in the faces. We decided to keep the scale bigger and it helped everything because of the scale of the smoke and everything really worked.

We came up with the idea of having the lava like a whirlpool, spiraling down. Mike Owens was working on a way to do the lava and we decided to go with bottom-lit lava, so it would be actually glowing and it would give off real light instead of using front projection or trying to matte something in. I’ve never seen really convincing lava in a film, and I know why, now: it’s almost impossible to do it. If you can make one element of it work there’s always another element that doesn’t quite work. We came up with a ‘What is this stuff down here? But it looks hot and dangerous!’ material and we had an enormous oil pump pumping hundreds of gallons of this stuff a minute. It was glycerine cut with water to a certain consistency that still looked thick, but was thin enough that the pump could actually pump it. There are pumps that will pump oil, but not very fast. We had to have speed to create the lava vortex. We got a piece of half-inch plexiglass about 12 by 10 feet, which was flat and curved down like a funnel in the center; this was our receiving trough. We had about four inches of glycerine constantly being funneled down into the pump system and it would then go back up to four jets that were all pumping in the same direction, so we got a spiral after a lot of work and trial-and-error.

“The set had to take the weight of the glycerine — enormously heavy stuff— and then we had to get enough light underneath it to make it look like it’s actually glowing. Paul Huston made the set quickly using the aluminum foil technique and some spray foam. It was about 15 feet tall by nine feet wide. On top of the glycerine we put a lot of black chunks so that through the black you could see the glowing stuff underneath. I lit the center of it hot, like a bull’s eye, and the chunks moved into it faster and faster. We had a lot of steam from the sides that was going up into the lens. Dickie Dova, one of the stage men, came up with the idea of taking a hi-hat camera rig and lowering it from the ceiling, about 30 feet, with a pulley system. We were shooting all this inside a tube with the camera looking straight down at our spiraling glycerine. Phil Tippett and Tom St. Amand sculpted the figures and Ease Owyeung made the cages. We rigged those up next to the camera and we did the shots virtually as they’d be done full size. We did a lot of takes, some with the camera tracking down behind the figure, locked off shots where the figure enters the frame and goes down through it; we did tilting to follow the figure going down — enough footage so we could approach the editing from a live-action standpoint.

The chase through the mine proved to be a gigantic undertaking, Muren recalled. “George and Steven wanted it to be the big action piece of the film — the showcase. Something spectacular with all the thrills and chills of a roller coaster ride, but the best roller coaster ride you’ve ever seen. I gave the responsibility of shooting that to Mike McAlister, whose work in Dragonslayer was really fine. He’s a good engineer, the kind of guy who’s good at putting together technology to make it do things.

“Mike went to about three amusement parks, took a video camera and shot rollercoaster rides. We looked at these and didn’t get anything very specific, but it got us the feeling of speed we wanted. All the time I was figuring: ‘How are we actually going to do this thing?’ There was no doubt that we could do it at high speed with figures about a foot high and shoot it with a high-speed camera, probably a four-perf because the camera would be smaller, and do it like a live-action short in a period of two or three weeks. I was in England when a lot of the live action was being shot on the full-scale set by Doug Slocombe [BSC], with smoke coming up, and I worried about how we could get those big plumes of smoke in anything other than a real high-speed shot. They had two full-size mine carts that ran on a real track looped around a stage with probably about 200 feet of travel in a big circle and they made all the close-ups and medium shots they could.

“While they were shooting this, Joe Johnston and Mike McAlister were here shooting a video version of the sequence, the very same way we did the bike chase in Jedi, with little models and paper sets of the walls and a quick, flexible track that could be bent into any shape depending on what ideas came up. We had a few ideas of things that could happen and, since it virtually didn’t cost anything, we shot some gags — funny little things that could happen in a mine car — that we didn’t know whether we could find a place for or not. We transferred them to film and sent them to Michael Kahn, the editor, and he and Steven would look at the stuff and start cutting together a sequence. Before we knew it, he’d shot all his close-up stuff over there and had our video stuff in between that we would later duplicate. This was the first time we had a chance to work with this technique.

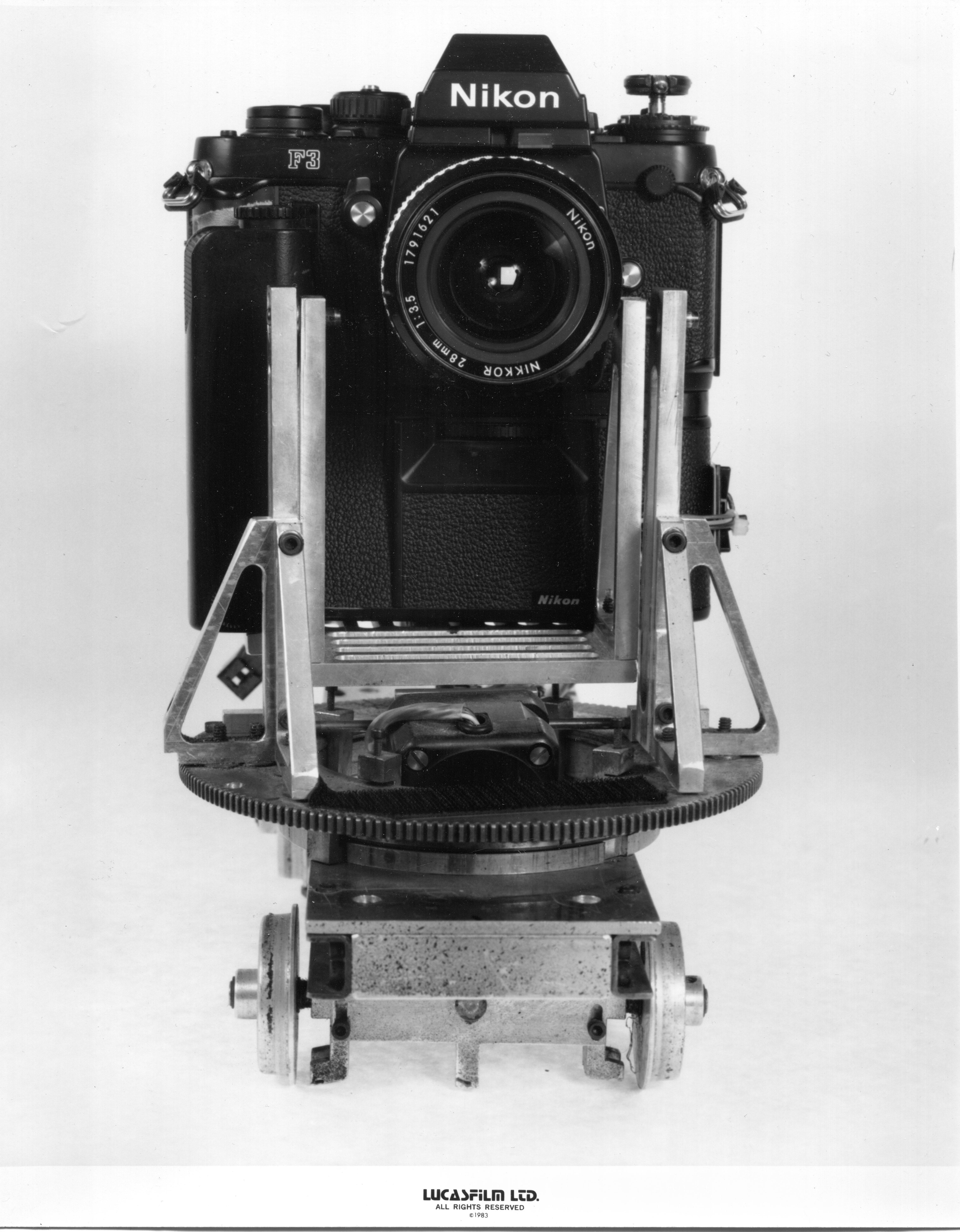

“By this time, I figured that the way to do it was with controlled stop-motion. Some time before I had started looking for the smallest camera we might be able to shoot it with, and one the things I came up with was the idea of using a Nikon still camera because some models had registration pins in the backs. We looked into these and found the registration pins were not made for our precision work. So, we got one of our house Nikons and asked our still photographer, Terry Costner, to get a bulk loader for it. We put as much as we could into the loader — I think it was 300 frames or so — and when we projected it we were really surprised. There were times when the frame would lurch way over to the side, then correct itself and then it might lurch and correct itself again. But that can be taken care of. The basic thing was that the transport was there, the lens mount, the focusing system, the motor, the drive — all the basic things to make a camera. Then I put Mike on the project of figuring out how to make the thing work.

“Mike knew we needed to slow the transport down so it wouldn’t jerk the film along but advance it slowly, and Mike Mackenzie, our electronics man, did that very easily using the standard Nikon motor drive. Mike built a 30-foot film housing on the back and kept it narrow, because it had to be narrow to scrape along the sides of the tunnel or we wouldn’t get our effect. We found out basically that by putting edge guides on it and by increasing the pressure pad greatly on the back of the film, it pretty well worked. It must have an incredibly accurate advance stepper motor in it, but we didn’t really need to do registration shots because there’s nothing static in it. You’d never use it for matte shots, but on something like this where it’s in motion, you’d never see the shake. Once we saw that was going to work out, which was pretty early, I gave the go-ahead on making the models.

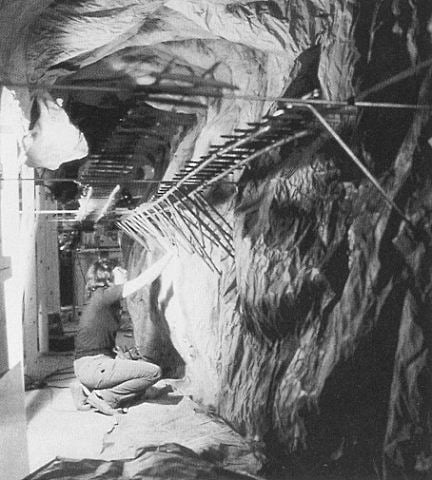

“Joe and I were looking to make the sets out of something like paper — keep ’em quick, cheap and dirty — because they’re going by so quickly you don’t even see them. The model shop came up with aluminum foil, which they used a lot, and a few parts were paper. The thing that really worked on that was that it was all in spotty light, where you’re going through little hits of light, and just those areas needed to be detailed and have props in them. It didn’t have to look good as a still photo; it was done more like a matte painting, more sketchy. It wasn’t for a museum, we were making it for the eye.

“By then, we had the video sequence cut, we had the models built including another set of models that were almost twice the size of the animation models that were used for high-speed shots when the carts were tumbling and people were flying out. Mike worked out the shape of the track and, working with about 12 camera and model shop people, he built a big loop pretty much combining all the different loops and angles to do the things Steven had liked.

“We came up with the smoke, a real nice smoke that holds in the air longer, and we had constantly circulating fans. It was made in winter in a warehouse across the street and it was very cold over there. Each element had to be taken apart and reassembled for each shot. It was a matter of pulling the foil off, or raising or lowering the track, which was made so it could easily be done. All the live-action people could do was a full-scale shot of the car going across the frame. If you see plumes of smoke coming up, that was shot on their set; our sets don’t have that, we never licked that problem. Instead, we smoked in the whole set and you don’t miss the plumes because the camera is moving all the time.

“Sometimes we had to shoot sequences they hadn’t shot over there, shots where there are two cars on different levels, or where they separate and go off to the sides. Our approach was to shoot as if we were really live-action guys and usually not worry about getting too close to anything. It’s really tempting to get too far back and make it look like a tabletop. Because we were shooting stop-motion we didn’t have much of a depth of field problem. There are a couple of shots where you’re racing ahead and there’s a car in the foreground with figures on it; we kept our focus on the background, which is what a real cameraman would do if he were locked into that situation. We constantly reminded ourselves, ‘How would this be done if it were real?’

“Sometimes we had to go along and tear apart the aluminum foil set to keep the camera moving forward. In some shots we’re right on the cars, pulling along with them and looking up at them, and the set actually is being built as we go along. Practically all of this was shot with a 24mm lens, which was the best lens to make the cave look big. Steven’s setup was shot with 100mms and 75mms. I was afraid it wasn’t going to intercut very well because of these radical lens jumps, but it does. We had the optical department add more shake to match it with the live stuff, where the cameramen had a lot of trouble following the action. Since we shot it in VistaVision, we had a lot of room at the top and bottom of the frame, so John Ellis shook every production composite we did. He looked at some of the live footage to guide him in how much shake the operator could do to match it up. It really helps tie it all together; it gives the feeling that it’s all being done at the same time with the same set of problems.”

There were plenty of problems in making the scenes in which the villain knocks over a huge water tank and floods the mine. “Paul Huston and the model shop guys put the big water tank together with the help of the stage crew, because it was a dangerous, heavy thing,” Muren said. “It held 1,000 pounds of water and it had to displace from one place to another in one second, so the stage boys put huge braces on it. The model was about five feet tall by eight feet wide, which was the largest size I felt we could handle safely. It would have been nice to have had it eight feet tall, but that was too risky as it would have weighed about 25,000 pounds. It was hinged at the bottom so that when it fell over it would hit the deck and stop and not go tumbling over the crew and everybody. It was an enormous deal — the sort of thing A. D. Flowers has been doing for years. We were coming in after dealing with models and toys and weren’t as much upon the laws of physics and so on; we even talked to A. D. about it.

“We had to build a very strong set that would take the impact of the water. We shot it outdoors at night with three cameras so Steven could select the angle he wanted and we got it in one take. Then we bluescreened in three people just in case you’re looking around for a scale; a couple of guys are running off to the left and another is running in the middle of the frame.

“The next thing is when they actually see the water and they run from it. That was done with four-foot-wide silo tubes, set up right against our shooting stage to brace the weight of the water going through. We had a six-foot-high silo tube about 12 feet in the air that was supporting the water, with a trap door in the bottom. The water would crawl down that and go through another tube at a 450-degree angle down into the back of the tube that had the set built in it, and that’s what started the water to rolling when it hit the main set — it was coming from an angle down with a lot of force, so when it hit the main set it spiraled through. It looked more interesting that way. Ideally, it would have been nice to do it with an 8 or 10-foot tube, but it would have cost about $500,000 a shot to do it that way.

“Long ago I saw Plymouth Adventure, where you could really see what air can do to the water,” Muren recalled. In this adventure production — made in 1951 and shot by William H. Daniels, ASC — special effects experts Arnold Gillespie, Donald Jahrous and Max Fabian, ASC, found that water surfaces could be miniaturized by breaking them up with blasts of compressed air. “We had three giant air compressors and off each one we broke about six hoses, so that we were hitting the water with 50 to 100 pounds of air as it came toward the camera, pushing it away and tending to break up the droplets to help the scale. It was really random as to whether a drop of water would form, but it was the best we could do with the time and money we had to do it. That was all built outdoors and shot under artificial light, but the top light leaking through was ambient sunlight. I had 5Ks off to the side for the colored lights coming through.

“We did six shots on that set. We set it up first as a prototype to see whether it would work and ended up using it for the actual shots. Lome Peterson and the model shop went in and redressed it so I could get new angles on it. Some of it was shot in VistaVision, but a couple of shots that had to be done at very high speeds were done in four-perf. The people in those shots were shot on bluescreen running on mirrored mylar, so we’d get a good bluescreen below their feet. All we had to do was rotoscope out their reflections. We spent a lot of time matching height and angles to get the scale worked out, and these were pretty tough composites for the optical people. Charlie Mullen and his animation department added shadows for the shots to tie the figures onto the ground. Then came all the little tricks we always do in optical with diffusion and flashing to help marry the two shots together.”

John Ellis, an optical effects expert who produced many of the composites, mentioned that he used every trick he could think of to add to the effectiveness of the scenes: “A piece of tape, a little work with a grease pencil, some vaseline on a glass were tools I used often to smooth out those shots.”

Tom St. Amand, whose model animation is much in evidence in the Star Wars saga and the remarkable Dragonslayer (considered by many aficionados to be the outstanding example of modern animation), revealed that the scale of his models in the mine sequence was based upon the settings in which they would be used. “The actual size of each of the puppets in the mine car chase was 10 inches tall,” St. Amand said. “The model shop worked out a scale at which they felt they could build the miniature sets. The puppets were sculpted by Phil Tippett and I designed the armatures which, to a certain extent, were based on the ones Harry Cunningham did for Mighty Joe Young. Really, armatures haven’t changed that much. We have a couple of new materials, but the process is essentially the same. There are hinges and ball-joints and swivels. Some of the construction was done by a very good machinist, Chris Rand. I didn’t have time to do it all because I ended up doing some of the sculpting for the larger figures, such as the three-foot tall lava pit people that we put into a cage and sent down into the pit. Phil did the girl and I did the guy, which we called Punjab. We hooked up a bunch of radio controlled stuff to them, to make the heads move and the arms go back and forth. We all worked on the clothes — Randi Ottenberg did the girl’s outfits and some of the hats and gear were done by Dave Sasala.”

St. Amand described the building of an animation model: “It starts with a clay sculpture and we make the mold from that. The armature gets custom-fitted to the mold, which is cast in rubber. I did all the animation in the mine car sequence. We did it the old way, moving them a little bit and shooting them frame at a time. We didn’t hook up motors or anything to the puppets, but the mine car itself was hooked up to a reel that moved it during the frame so that it blurred. They’re such fast shots that you can really get away with a lot. The biggest trouble was access to the models in these little cars. We had to chop off the legs to even fit them into the cars. I had to build little hinge joints on their bottoms so they could go up and down and rock back and forth. On the side of the mine car, which was built by Charlie Bailey, we had a little lead screw into which I could insert an allen wrench to tip the car. In scenes where the car went around a sharp curve the whole car would tip, and I’d have to tip the little people too, the opposite way. The whole idea was to make it look scary and do things that they couldn’t do with the actors that could have killed them. This was harder to do than the dragon or the kids on bicycles in E.T. because you know what people move like and if it looks fake people know it, something like a sixth sense. So I spent a lot of time looking at the live-action footage, observing the way Harrison Ford moves and matching the moves. With something nobody’s ever seen before, like the giant Walkers in Return of the Jedi, you have a lot of leeway; you just say, ’This is a Walker, we made it and this is how it moves.’ And who’s to say no? But on these human figures, if they look weird, it’s bad.”

The size of the sets created many problems for St. Amand: “In some of the sets there wasn’t room for me to be in there and I had to do a great deal of it through trap doors. Where Indy’s car is on one side of the track and the bad guys’ on the other, I’d have to open up these little doors in the set and reach through to do all the good guys, shut the doors, crawl under the set, open up the little doors on the other side, do all the bad guys, shut those doors — and then we’d shoot one frame. This would go on for 100 of 120 frames! We were fortunate: some of the more complex shots we got on the first take. Some of them took 10. You just keep going back and back till you get it right.

“Mike McAlister did the programs for the movements of the mine cars and he would vary the speeds so that they didn’t always look like they were going at the same speed. It was neat, and that’s how it should be done, but it was hard for me to animate. The good guys had to grab hold of the bad guys and there’s a scene where they had the kid actually stretched across the two tracks. Indy would be pulling on one end of him and the bad guys would be pulling on the other. Those were the hardest shots, because the positions would change and I had to always animate the figures to compensate. We were constantly forgetting to turn the cart lights on and we would be maybe io frames into the shot and I’d say, ‘Mike, the cart lights are off,’ and we’d have to back it up and start again.

“We had to shoot most of these scenes in smoke. It seemed like miles of those little caves that snaked all over the room. We were always just a jump or two behind the modelmakers. To keep the smoke at an even level, we had a fan blowing, which was incredibly cold. It was a crazy, surreal environment. It was fun. It was like a chance to play Indiana Jones, always thinking, ‘what would Indiana Jones do in a tight spot?’ It was more of a character thing than a bunch of Walkers going around shooting Ewoks.”

According to Muren, the end of the flood sequence — when hero, heroine and moppet are thrust out onto a crumbling cliff edge — was “really fun to do.” To a dedicated effects artist, “fun” and “challenge” are synonymous. “That was a matte painting of the cliff with a scene of the players that I shot in England rear projected into it,” Muren said. “I did it as if it was a helicopter shot. There’s a bit of movement in it and it really helps take the edge off that shot. We tried it first with a pullback, but when we were running the daily of an early take we found it was better if we moved in, for some reason. So we did the actual shot sort of shaking around and moving in. Chris Evans did the matte painting and it was a really nice job. From here on the painting was very tough because everything happened in bright sunlight and you can’t hide anything in that.”

Muren encountered another big challenge in staging the sequence in which the water bursts out of the cliffside. “That was a very large model with figures about 14 inches high shot in bluescreen and using a big dump tank about 20 feet in the air to send the water through the cliff facing. The cliff was made of styrofoam with plaster over it and was about 15 feet high and 24 feet wide. I spent a lot of time working out the scales, constantly battling against the argument that the bigger it is, the better the water looks, but also the more dangerous and costly it is to actually shoot it. So we got it about as small as I felt we could do it safely and with the amount of money we had, and put a lot of wind to blowing on it. We shot at 85 or 90 fps. The opening in the cliff was about two feet wide and we bluescreened the players into it and rotoscoped them off as the water burst out. We got a nice action on the wave when it comes out toward the camera, preceded by debris shooting out which was filmed against black and matted in.

Another shot failed to satisfy Muren, but it had to be retained in the film. “It was a horrible shot to have to do, but we gave it a try,” he grimaced, “it’s a down shot on Harrison on the cliff with the facing breaking away, and a real river in the background. We spent a lot of time trying to get it to come together, but it was a really tough shot. We couldn’t leave it out because Harrison had some dialogue in it. We never quite got it right and I’m not happy with that shot at all.

“After that was another of the harder shots of the show, in which the water is still coming out as viewed from above and you can see the people on the right going out and Harrison at the left climbing up over the cliff facing. That was the same model we had when the water broke through. I didn’t want to risk doing any sort of a composite with any edges, so we bluescreened him, shot him climbing up a skeleton frame against blue and his hands sort of matched some hand holes we had built in the rock. The animation department spent a lot of time adding a shadow for him and tied it right together. We were really worried about the shadow, but animation did a great job. They added some other little handholds, too. The people in the background walking away also had shadows added.

“In the background behind that shot is a very large backing that the matte department painted because they didn’t want to matte the water over the scene. Steven really wanted to see a vista back there, so they painted a mural about six feet wide and 18 feet high that’s on the left side of the frame so the water is really going over something.

“It’s funny, but a lot of times you don’t know what the hard shots are going to be and other times you know right from the start. Those two shots, we knew from the beginning, were going to be tough.

“Later on, when they’re on the suspension bridge and it breaks, what they actualy had for us to work with in England was a set Scotty had made which was about 50 feet high and 80 feet wide, with the bridge hanging about halfway down it. We extended the vistas all the time you see the bridge. From the side views we extended it with paintings of the cliffs going off with Sri Lanka in the distance. For the upper shots, supposedly from the bridge, we built a big pedestal about 50 feet high and about 12 feet from the cliff facing, and we bridged it with scaffolding. From that bridge, we shot the down shots. We were really worried about shadows from the scaffolding on the cliff facing. We shot all those in VistaVison as locked off as best we could get on a scaffold. Beneath the actors were cushions to catch them, and they were all strapped in with hidden wires and cables. I put the camera out far enough that most of the figures were backed up with a real cliff. Only down at the bottom did they extend over the edge to the cushions. We put a fabric down there to look like the color of rock, but we ended up eliminating it and we rotoscoped them with the kicking feet going over a painting which extended 300 feet off the cliff.”

Water again proved a difficult element, Muren noted. “We searched all over the Western Hemisphere in the fall and winter to find a river that travels north and south so we could get the sunlight. They practically all go east and west. We found one right near the Glen Canyon Dam and shot all the water stuff on that. Steven wanted it to be about 500 feet down to the water to make each shot as scary as possible. We matched the sun angles as best we could. Then he came up with the idea of putting alligators in there. About five buildings down from ILM is an auto repair shop where a man raises baby alligators. They’re two or three feet long. We got the man to bring his alligators over. We made a tank about two feet deep and put in four inches of water which we colored with milk. We soft-lit the whole thing and gators tend to be dark, so what we had then were the silhouettes of the gators disappearing into something light. From the top of our stage with the widest lens we could get, a 15 mm, we shot gators doing all sorts of things. We’d feed them chicken and it took about three hours to shoot enough footage, which wasn’t much because they only do things when they want to. We probably found a good 15 seconds worth of film. We used sections of it over and over again, finding little bits that work. We reduced it optically still further, at least 50 to 100 percent, and that was optically bipacked so that we had black silhouettes against white. Then we garbage matted the rest of the stage out and bipacked them over the water — and that was what we used for all the long shots of the gators. We had thought about doing them with animation or sliding models around on tracks, but this worked out fine and the gators had a good time.

“Within that sequence, we have people who fall off and we did them with one of our regular track cameras, motion-control rigged, using figures about a foot high. Tom St. Amand made them and did the animation, too. We looked at some footage of real people falling off things to get some idea of what the actions would be like. We added shadows so that as they fell they cast shadows on the cliff. There were a lot of complex elements in those shots to tie them together. They all had to be steady because there were hard-edged mattes working in them.

“Then, at the end, Steven came up with the idea of following the main villain down the cliff when he fell. I was worried at that point about putting a miniature into it and how much it would cost to build a miniature and make tests and how big the miniature would have to be at the start of the shot when you’re seeing a big vista. At the end you’d only see a little vista, but at the beginning, you might need something 40 feet wide. When we were shooting the live-action footage of the raft going down the hill, that was done with something called a descender, a cable attached to the back of the raft for safety. It slacks and lets the cable out, but put a brake on and it stops. I wondered if we could take that and actually put it over the edge of a cliff with a camera on it and drop it down. We needed a cliff sheer enough that we could do it and see what we could get. We might get something that might not work, but then we’d always have the miniature backup.

“Mike Owens went out near Glen Canyon Dam to a pretty sheer facing with a crew. They spent two days out there and dropped the camera four or five times over the side of the cliff 400 feet, shooting at — I think — three frames per second. That became the background plate, and then we bluescreened in stop-motion the falling dummy, until it’s bouncing off the side. Every time he hit he knocked up broken rock and dust shooting by the camera. We added a shadow to him that sometimes shows up and sometimes doesn’t because of the contours. It was real tough shot, but I don’t know how else we could have done that.”

St. Amand recalled that “we did it three times and it was difficult. It was hard for Dennis because he had to line it up as you actually follow the body down the cliff. The animation was hard because he was so big in the frame. Another tough one was the scene where three guys fall off at the same time, a down shot with everybody’s arms waving and legs kicking and skirts blowing in the wind.”

Film editors Howie Stein and Mike Gleason were in charge of assembling the special effects material and making certain that it would intercut properly with the main-unit footage. It is, as Stein admitted, “a very specialized, rather unusual field of editing.” They are involved in the pre-production planning long before the cameras turn and work continually until ILM’s job is completed. “Work here is slow, frame by frame, so it’s critical to keep wasted effort to a minimum,” explained Stein, who made documentary films for the government before coming to ILM six years ago. “We work with frames, not footage. We have to be aware of what is being used so there’s no time wasted. We’re the liaison between what’s shot at ILM and the actual live-action people. We assure that it all fits in and also take all film elements and determine which will be combined.

“We start with the storyboards, then later we get to the practical shooting and all the changes that weren’t planned. We make a video version to cut together to establish continuity and see what’s in a sequence even before we make a rough film cut, which is on black-and-white film. At this stage we can make subtle changes and borrow pieces from other shots or from our library of background elements to help put a continuity together. The black-and-white temporary editing print is made from work prints and they make quick-and-dirty composites. When we get to the actual color work it’s a very precise process to make sure that what we’re shooting will — far down the road — match what will be shot later. Good creative judgments save a lot of unnecessary optical work.”

According to Stein, only one thing is always certain: “Inevitably, no matter what the deadline is, that’s when the shots are done.”

Our complete discussion with Steven Spielberg about directing Temple of Doom can be found here.

If you enjoy archival and retrospective articles on classic and influential films, you'll find more AC historical coverage here.

Access the every issue of AC and every story from more than the last 100 years with our Digital Edition + Archive subscription.