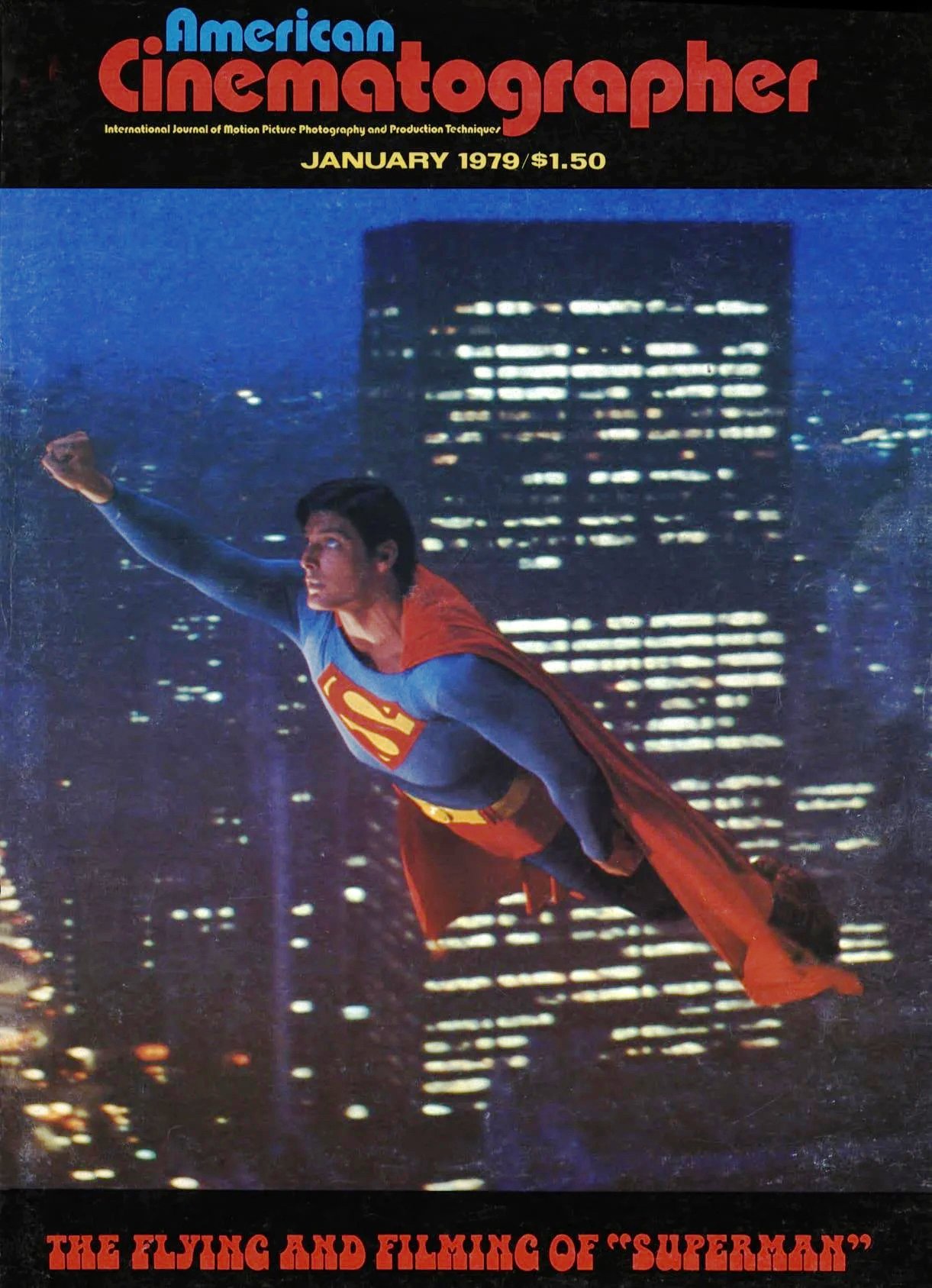

Superman: Directing the Filming of an American Superhero

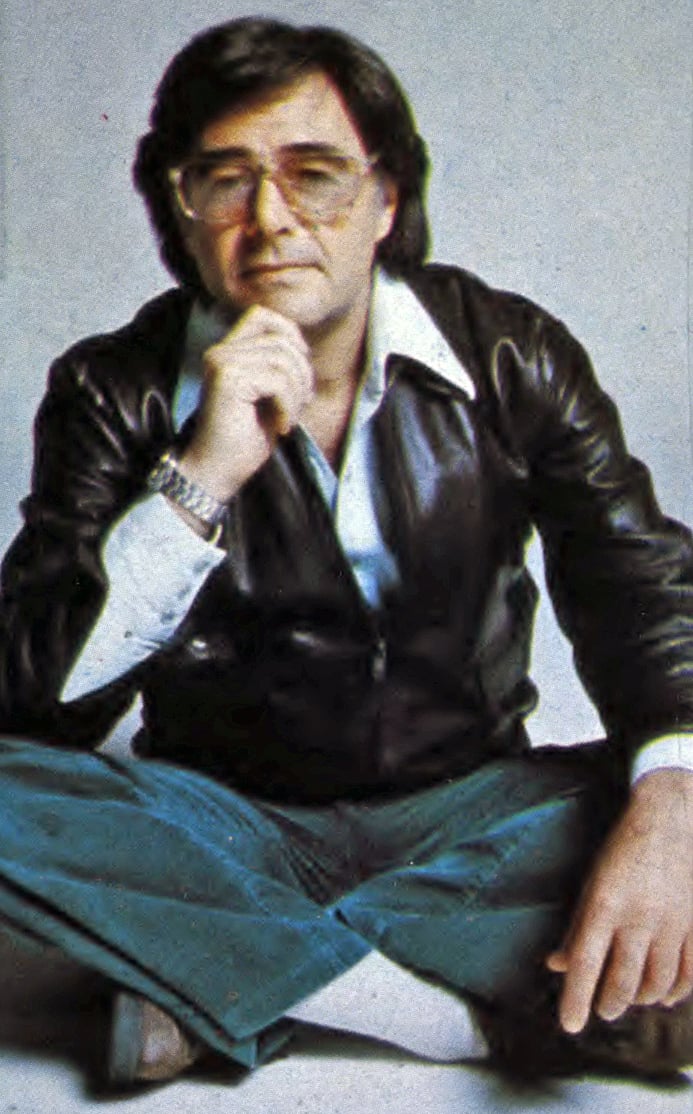

Like the ringmaster of a 12-ring circus, this super-talented director, over a two-year period, functioned as leader, father-confessor, resident psychologist, and inspiration to a huge crew of actors and technicians.

By David Samuelson

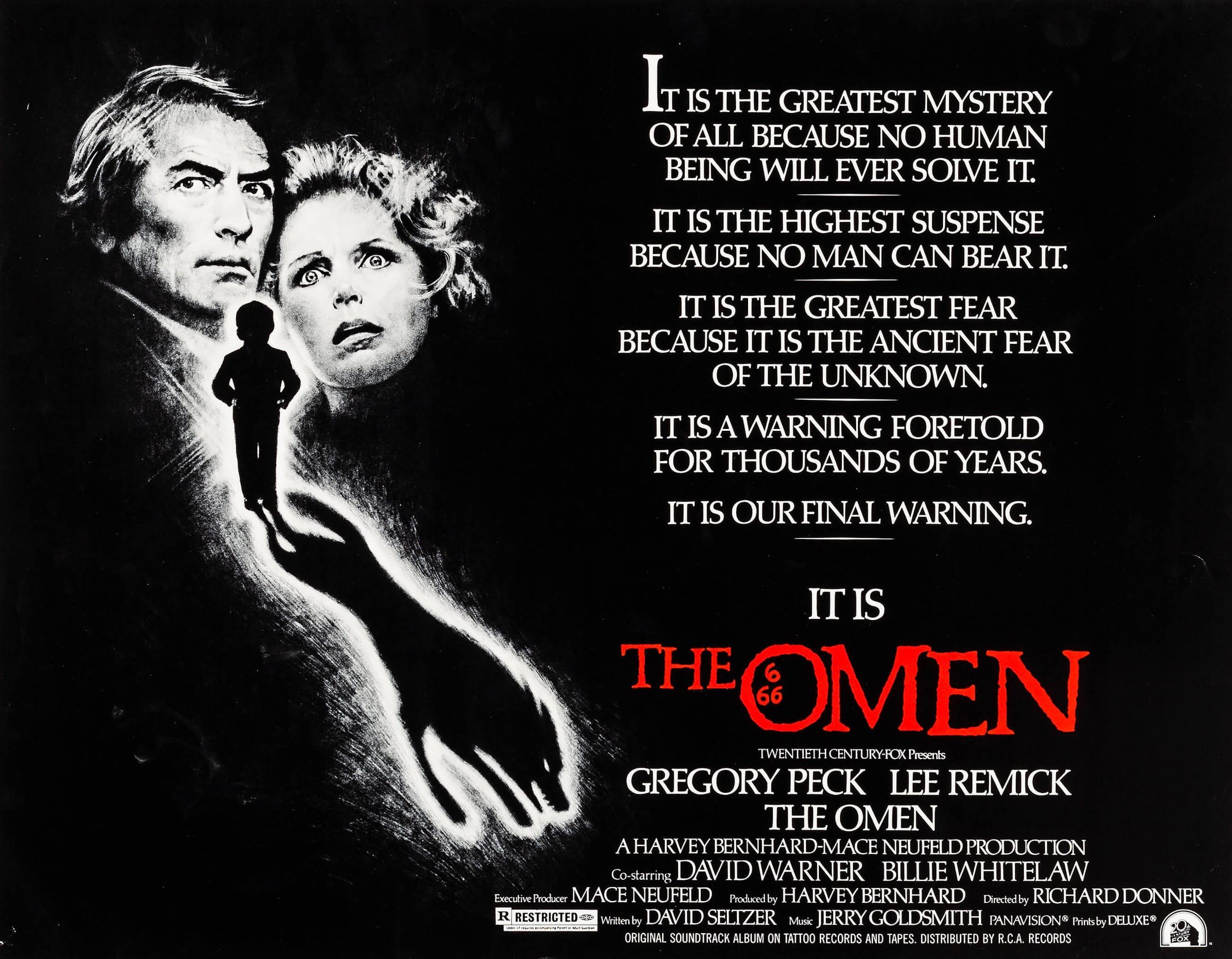

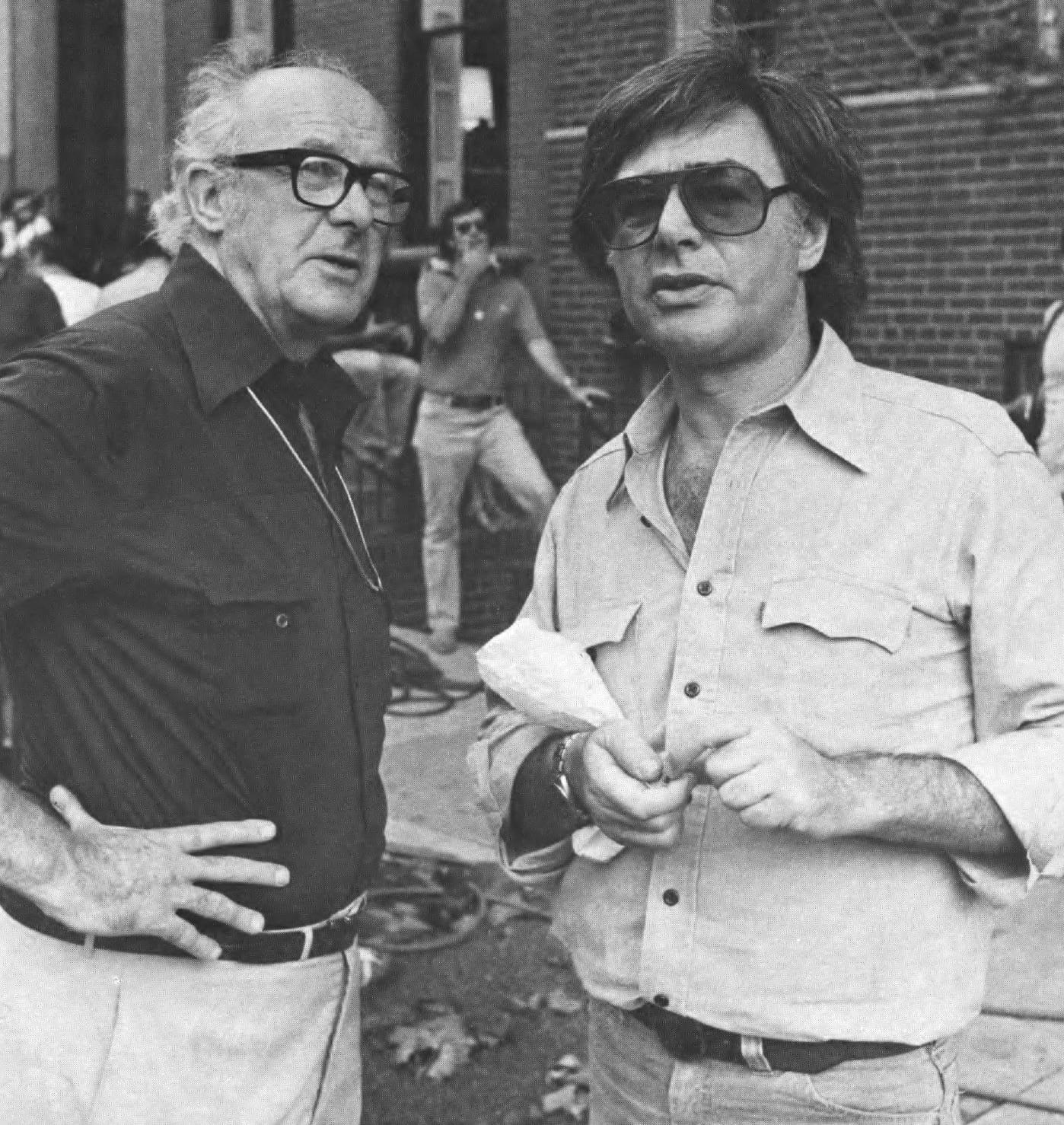

It was the summer of 1976 and The Omen, directed by Richard Donner, was climbing toward the $100 million mark in worldwide grosses.

That’s when Donner received a sudden transatlantic phone call from Paris: “This is Alexander Salkind. Do you know who I am?”

“No,” replied the director.

“I’m producing Superman,” Salkind informed him. “I’ve just seen The Omen. It’s marvelous. I want you to direct our picture.”

After receiving assurances that he could have complete control of the script, Donner’s reply became a commitment to two years of exhausting, absorbing, richly rewarding effort. It would have a dazzling stellar cast, eye-popping special effects and locations all over the world, with two London studios as home base.

It would have one more thing, Donner was determined. Verisimilitude.

“It’s a word which refers to reality,” he explains. “I had it printed on big signs which were sent to every creative department — wardrobe, casting, special effects, you-name-it. It was a constant reminder that if we gave in to temptation, and parodied Superman, we would only be fooling ourselves.”

Reality — in a movie in which a Man of Steel from the planet Krypton, flies through the air in a crimson cape?

“Absolutely,” says Donner. “Of course, it’s bigger than life, but there is reality in the characters. It’s a comedy, a love story, an adventure and its own thing. “But it is always true to the ‘Superman’ legend.”

Born and raised in New York City, the son of a gifted woodcarver, Donner was the first in his immediate family to enter show business — with the exception of one “black sheep uncle” who produced musicals during World War II.

His first ambition was to be an actor. After a succession of “five-line parts” off-Broadway, he found himself working with director Martin Ritt on a TV production of Somerset Maugham’s Of Human Bondage. Ritt had some good news and some bad news for the young actor. The bad news — first — was that he couldn’t take direction. The good news was that Ritt thought he’d make a fine director. “Show me,” said Donner, and Ritt named him to be his assistant.

“I’ve been reluctant to allow any of the footage of Superman to be seen in trailers or on television because in context it’s magnificent, but on a TV or out of context, it’s just a shot of a man flying.”

— Richard Donner

Tranferring his new career to California in 1958, Donner directed commercials, industrial films and some highly successful documentaries. The first Donner-directed dramatic effort to cause excitement was Wanted: Dead or Alive with a newcomer named Steve McQueen.

An unbroken succession of “Movies of the Week” and series episodes of shows like Kojak and Bronk followed. His special Portrait of a Teenage Alcoholic scored with both the critics and the Nielsen pollsters and he achieved a rare reputation, among network chieftains, which kept him constantly in demand. Virtually every time Donner directed a pilot, it went on the air as a series.

Finally, producer Harvey Bernhard asked him to direct The Omen. He sensed that in its satanic tale was the potential for a truly nightmarish experience. But it could not be treated with traditional horror trappings.

In a meeting with Alan Ladd, Jr., production head of 20th Century Fox, Donner was asked how he planned to handle the script. “Eliminate the obvious,” he replied. Ladd approved, and within a year, Fox had one of the most resounding hits in its history.

Donner had little time to bask in the success of The Omen. Superman became an all-consuming challenge and there were days, one suspects when he wished that Salkind had dialed the wrong number.

“After working seven days a week, 15 hours a day, I’d sometimes go home at night and dream about doing a two-character love story, set in one room,” Donner recalls. “The challenges were enormous — they had to be — and many of them were of our own making. That’s what you thrive on in this business.

“If there were two ways to film a scene — an easy way that would look easy on the screen — and a way that we all agreed was impossible, the answer was never in doubt. We’d shoot for the impossible.”

In the following interview, conducted in London by David Samuelson just after the completion of principal photography, Donner talks about the trials, tribulations — and matchless excitement of directing Superman.

American Cinematographer: There has been an extraordinarily tight security screen around the filming of Superman. The “closed set” really has been “CLOSED.” Would you care to comment on that?

RICHARD DONNER: To my mind, it’s not been a cloak of secrecy; it’s been a necessity. Steven Spielberg, who is a very dear friend and an incredibly talented human being, had a cloak of secrecy around Close Encounters of the Third Kind. His primary reason for that, I think, was to keep people from seeing the special effects until they actually saw them in the completed film. And rightly so because when I saw those things happen for the first time in the theater I was spellbound. I would not have liked to see them beforehand. But when viewed in the total context of the film they were sheer genius.

I feel the same way. I have been reluctant to allow any of the footage of Superman to be seen in trailers or on television because in context it’s magnificent, but on a TV screen or out of context, it’s just a shot of a man flying. That explains my reluctance to prerelease any of the footage.

As for allowing anyone to see it being filmed or exposing our methods of doing it, that goes back to when I was a child in New York, where I was brought up with Santa Claus and, at a certain age, my best friend told me that there was no Santa Claus. He loused up Christmas for me for the rest of my life, in an odd sort of way. Well, Superman is Christmas and he’s Santa Claus and I don’t want to ruin the illusion for anybody. Superman flies and he flies magnificently, and that’s one thing no critic in the world is going to take away from me. But as for the veil of secrecy, I didn’t want people to come in and see how it was done. I didn't want it seen piecemeal. I wanted it to be seen in its total continuity.

Your “veil of secrecy” is perfectly understandable, if you are talking about what goes into a fan magazine, but do you feel that the same restrictions should apply to a technical magazine like American Cinematographer?

Well, I find American Cinematographer technical and I also find it very well edited and good reading. I lecture a lot around the States when I’m home, at universities and film schools, and the ASC magazine is regarded by film students as a Bible, a very good manual. I find it amazing. It’s documented in such a good fashion that I don't call it merely a technical magazine. I call it an insight into the film industry. There are personalities involved; there are humanities involved; there is everything.

The Russians describe it as “a window on current film production technology.”

But it’s more than technology. It’s humanities, too, because when they interview people (which I find terribly enjoyable to read), the personalities of those people come through. I know a lot of those people. I know their shortcomings and their greatnesses, and when I read what they’ve said I become aware of the problems everyone else on that picture had. So when I think of our film as being a major subject for coverage in American Cinematographer, I hope the publication will dwell not only on the technical aspects of Superman, but also on the humanities and personalities involved in its production. It was people who made the technical aspects of this picture work-and I mean totally. I’m serious when I say that if I had hired nothing but great technicians for this production, we would not have the film that we have today. One of the most important factors for me in selecting these people and working with them on a continuing basis has been not only their technical involvement but their emotional involvement because their emotional involvement contributed so much to their technical achievement.

In what way?

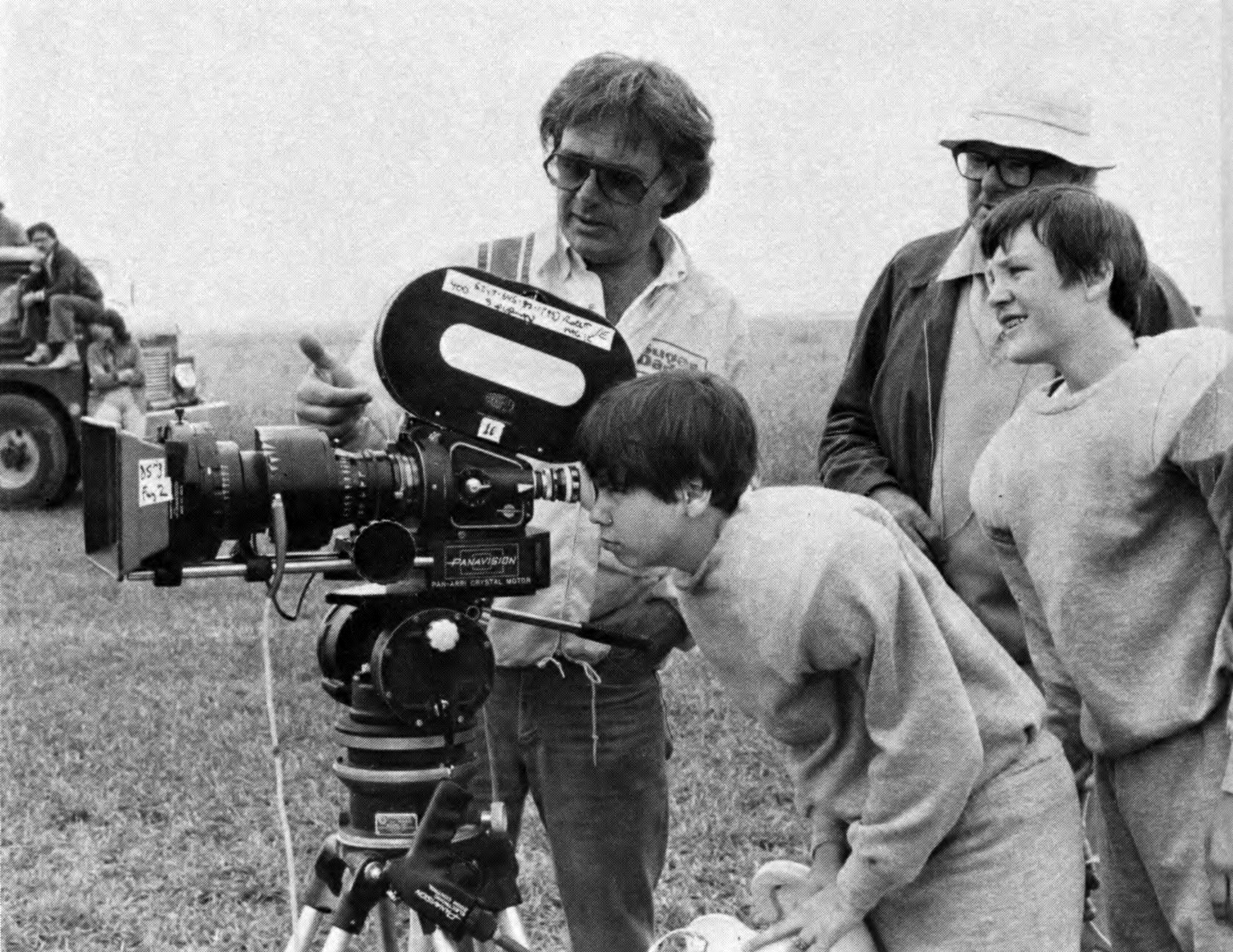

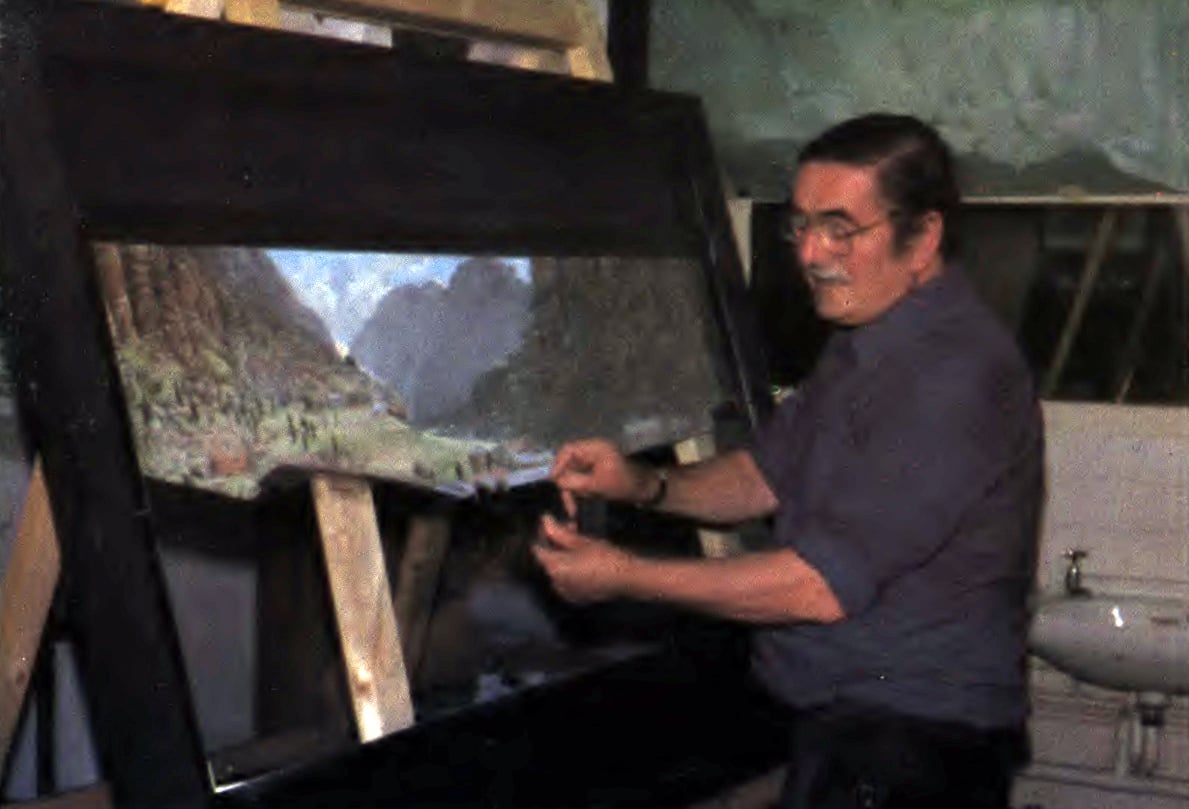

A truly great technician may go by the book and know that there are certain things that can possibly be done, and other things that are impossible to do. While we know that the word “impossible” does not really exist, certain great technicians will still stay within the framework of what they do best and they will deliver just that. But there are other great technicians who will become emotionally involved in the project and so charged up by it that they will go to other people and query, investigate, experiment, and push themselves far beyond the knowledge they already have and the techniques they have used before. In the beginning, on Superman, as on all pictures, the responsibilities were all sharply departmentalized. We had Roy Field in charge of opticals, Colin Chilvers in charge of special effects, Les Bowie in charge of matte painting, Derek Meddings in charge of miniatures, Denys Coop in charge of front projection and, of course, the genius of Geoff Unsworth, who provoked everybody beyond the limits of their own knowledge.

But in the beginning, I would hear things like, “That’s not my department.” The fact is that I had a major problem on this picture, because I was as naive as anyone else — even more so. I read a script and rewrote it, but the project was approached like Indians attacking a fort. The script would indicate that Superman flies here, he flies there, he does this, he does that, without anyone ever really figuring out how he was going to do all that. I mean, if I were the producer of this film, my first venture, before getting involved with anyone or anything, would have been to invest $100,000 or whatever into proving that I could make a man fly. If I were sure I could do that, then I would go out and make a picture. Nobody did that on this picture. They simply turned a script over to us — which we would change — and there were all these incredible effects to be created.

Do I understand, then, that the most crucial aspect of the production was whether or not you could get Superman to fly believably?

Absolutely. A film like Superman can work only if the audience accepts the fact that a man is flying. They will react with gasps, sighs and screaming, but in an odd sort of way, our feats in this film (hopefully) will be totally taken for granted by the audience. They will applaud them and they will be excited by the things the character does as Superman, but they won’t be impressed by “special effects,” as they have been in other recent films that have been made.

“A great deal of the credit for this goes to Christopher Reeve, the actor who plays Superman. People ask me, ‘Where did you find him?’ And I say, ‘I didn’t find him. God gave him to me!’”

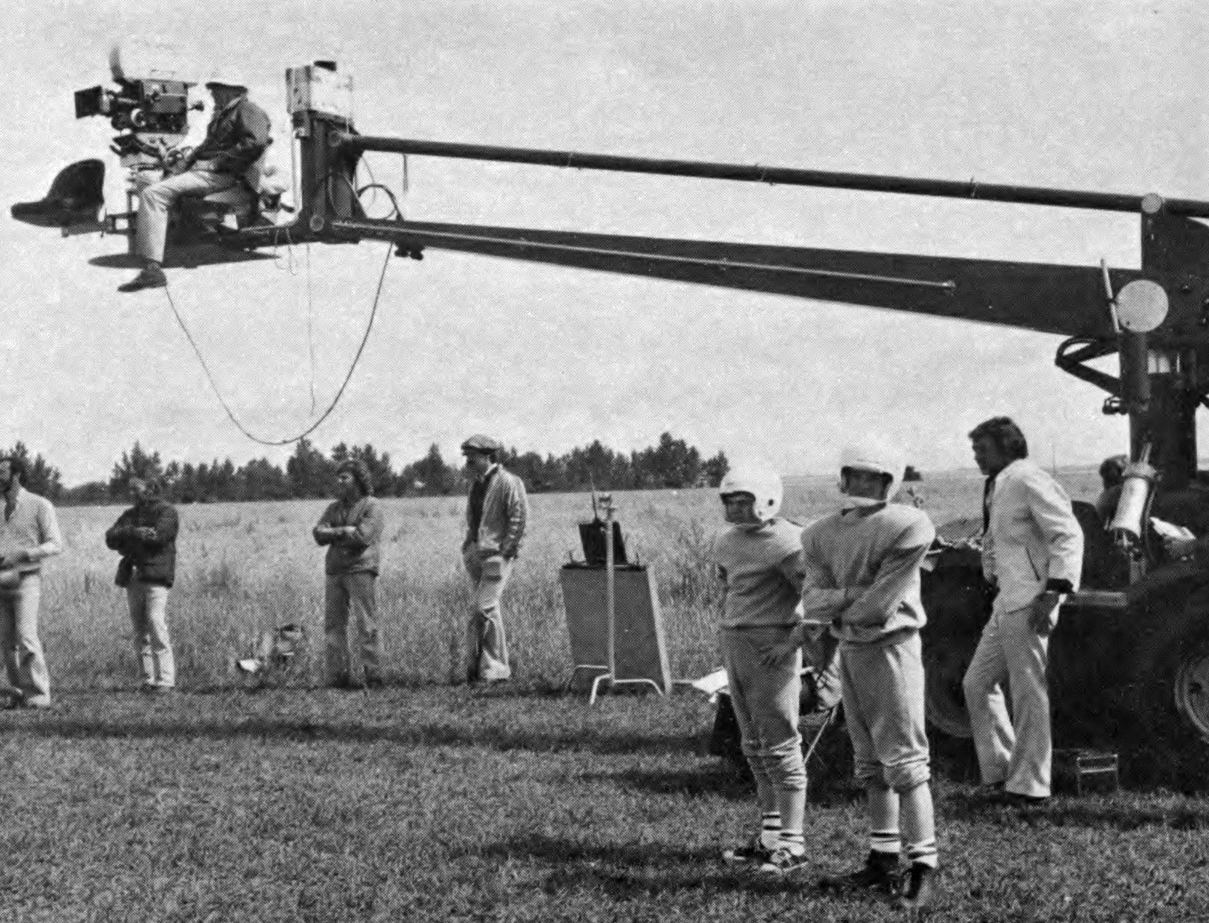

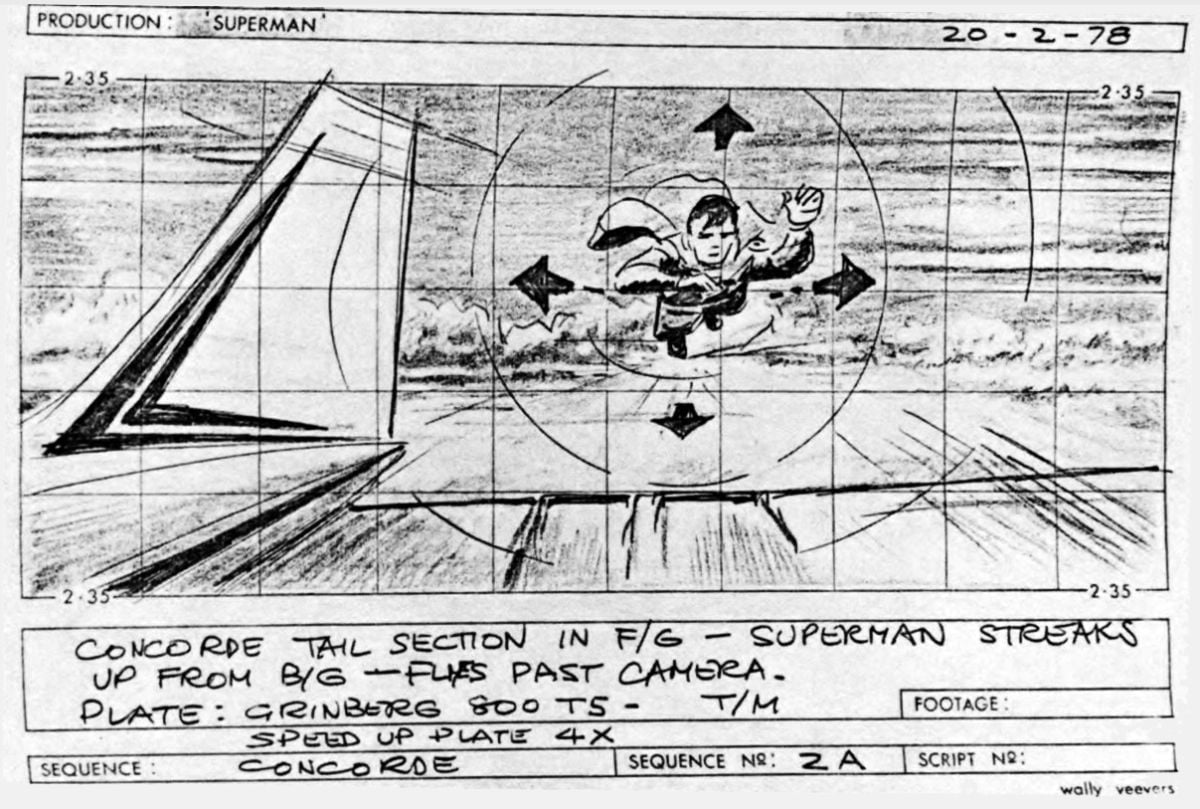

Why is it particularly difficult to make a man look like he is flying? Is it the take-off?

It’s the take-off, the landing, the attitudes in flight. To put Superman up in the air at a one-dimensional angle and keep him like that would have been an easy answer to the problem but not an adequate answer for me because it wasn’t the ultimate. It was what I had seen before, or what had been done before, in certain motion pictures, but I wanted a more convincing illusion of reality.

Star Wars and Close Encounters enjoyed a tremendous advantage over our Superman project. I choose these two pictures as examples because they are the most contemporary and most talked about special effects films that have been done. They had the advantage of dealing with inanimate objects — space machines — that they could fly from place to place. When these spaceships came into the picture, they came in with a great deal of noise and light, and, being inanimate, they could be computerized for multiple exposures on the film. In other words, their movements could be repeated precisely in order to add piece after piece of foreground and background detail. Since they were all inanimate objects, this was relatively easy to do although still tremendously complicated.

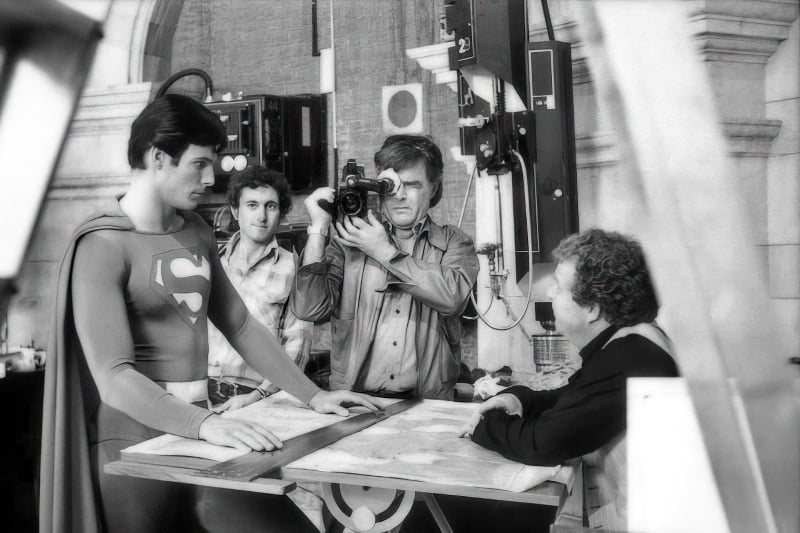

stance in front of the stars and stripes here.

In Superman, we were dealing with a man who is flying. You could never repeat his movements precisely, even with the best computer in the world because he was a human being. If a finger moved in the wrong direction or his cape fluttered slightly differently, you could never reproduce that exactly. So we faced an incredible problem because we couldn’t computerize the operation. We could computerize movements of the background or camera, but we could never repeat the human movements precisely. Secondly, as I mentioned before, the spaceships came onto the screen with a great deal of noise and light. Sitting in the theater, you were shaken right out of your seat. It was magnificent! But Superman does not make any noise or emit any light when he flies. This meant that there was a danger that his flying could seem uninteresting, especially if we simply had him going left-to-right, right-to-left, up or down. As we have actually filmed him, however, he twirls, he loops, he spirals — he flies! A great deal of the credit for this goes to Christopher Reeve, the actor who plays Superman. People ask me, “Where did you find him?” And I say, “I didn’t find him. God gave him to me!” He is probably not only the finest young actor I’ve worked with during my entire career, but he looks more like Superman than Superman does, and more like Clark Kent than Clark Kent does. He enjoys playing the role of Superman, as well as the buffoon who is Clark Kent, the bumbling, stumbling character who must isolate himself from the others by being a silly man. On top of that, Chris is such a dedicated young actor. Being a pilot in his private life, when Chris starts to feel the act of flying, he flies like nobody else could ever fly. When he is up there, that kid is flying! I mean, he can feel the thermals, he can feel the movement, he can feel the exhilaration. He’s phenomenal. His hand movements, his attitudes of anger flying around in hot pursuit, how he shifts his body movements — it’s just brilliant! His performance enhances everything else we’ve done.

From the technical standpoint, would you say, then, that your major challenge was to keep him from looking like nothing more than a cardboard cut-out soaring against a background?

Yes. Our main problem was to keep him fluid, mobile and looking like you could see 360 degrees around him at all times — and, miraculously, it does come off. When you really think about the fact that we were using wires, front projection and polearms, how do you really show in one shot all those angles of flight? That is what we have accomplished.

Can you tell me a bit about working with Denys Coop, who photographed the flying sequences?

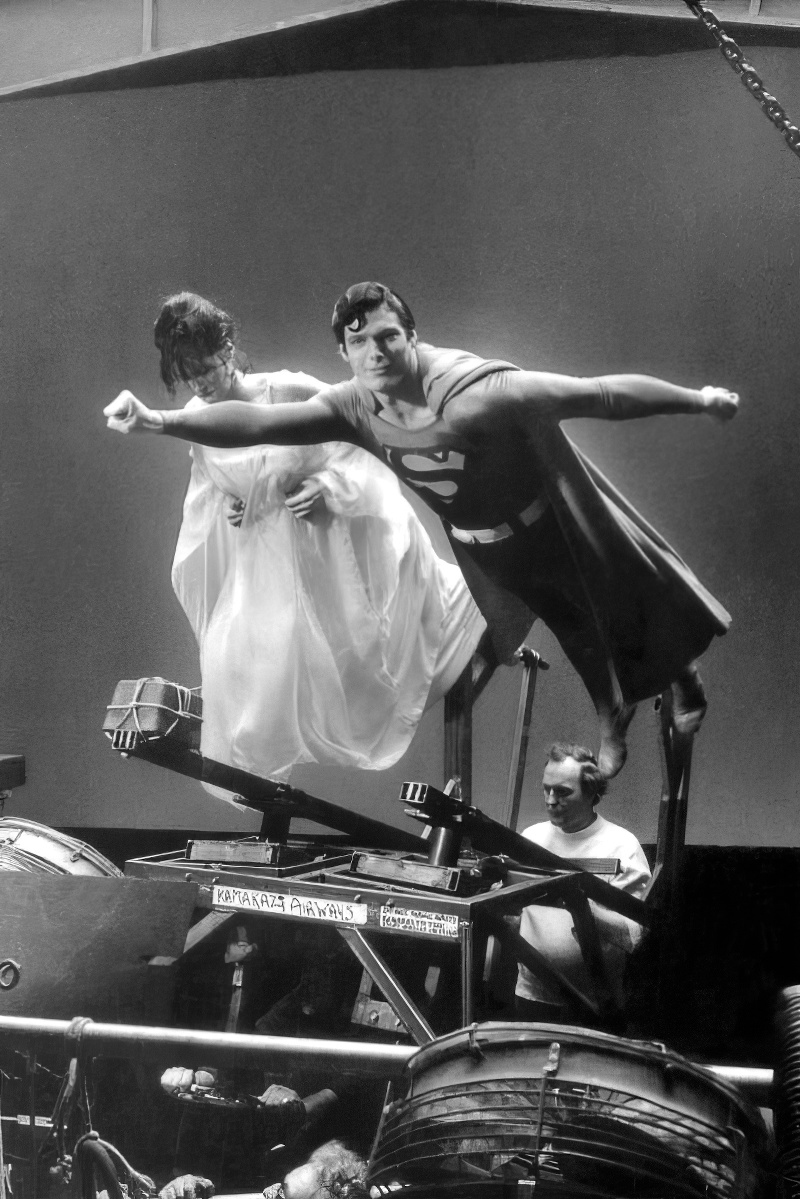

filming spectacular flying scenes with

front projection.

Well, I will say that Denys deserves as much credit as any other human being in this world for bringing so much to the flight sequences of Superman. I mean, he is just a genius. I am terribly provoked and excited by him and I think he’s an incredible man.

He’s a top-flight lighting cameraman in his own right — but here he was doing a sort of special effects job.

It’s more than a special effects job. It’s a process that was totally in its infancy, perfected by us. Denys came to me when we were about to throw out a device that we had been experimenting with and begged me to put more time and money into it because he knew he could make it work. I had trust in him, and he did make it work. He conducted total experimentation day after day, trying and trying until one day we sat in the theater watching dailies and saw the final result. I nearly cried when I saw it because it had been such a long, hard pull. It was so exciting that I just couldn’t believe it.

You used both the miniaturized front projection rig, as well as the system with two zoom lenses?

We used both. The particular application was planned quite carefully for whatever the problem was within a specific flying shot. You made the observation that Denys was photographing special effects, but he was actually filming dramatic scenes. In addition to capturing aerial acrobatics on film, he was delivering a dramatic moment, a moment that had to be lit and planned to be as dramatic as if it were taking place in a room or an automobile or wherever. But the lighting was ten times as difficult for Denys because he had unique light balance problems and exposure problems and those god damn machines would never work right when you wanted them to. But while coping with all these purely technical problems, he still had to deliver to me the lighting that fitted the dramatic mood or situation. Sometimes the combination of dramatic and technical demands was just incredible — such as in the sequence in which Superman first meets Lois Lane. There was so little light that Denys had to shoot at 8 frames a second and the actors had to slow their movements down to one-third normal. There were so many days that we had to reshoot and reshoot and reshoot until we got it right.

You started to tell me earlier on how, in the beginning, all of the technical functions were sharply departmentalized. Could you follow through on that train of thought?

Yes, they were departmentalized, just as in any normal motion picture, and it became my responsibility to coordinate all those separate functions. Every night there would be meetings in my office with drinks and everybody just sitting around and rapping because there were no answers. There was nothing on paper to guide us in what we were doing. Little by little departments were totally eliminated and everybody started to work in each others’ departments. It became the most homogeneous group of filmmakers that I’ve ever had the good fortune to work with in my life, and that has ever been organized into a motion picture crew, in my opinion.

Does that include the crews you’ve worked with in America?

I think that America has probably the finest motion-picture production facilities and technicians in the world. Yet, in all honesty, I must say that there’s no way that Superman could have been made in any other country in the world except England. The reason for that is that there is still a studio system in America. Universal Studios is a major operation. The Burbank Studios is a major operation. Paramount has its own facilities, also. But the point is that England is freelance, and to get all these top-grade technicians under one roof in America would have been impossible. I could not have gotten the best matte painter from Universal, the best special effects man from Warners, the best miniatures person from someplace else. These people would have been busy working on projects at their home studios. But in England, I can pull the people I want from anywhere and put them together under a freelance system. There’s nothing wrong with the American system; it has turned out some great films. All I’m saying is that it wouldn’t have worked in this case. I would have had to make too many concessions.

It does seem that here in England you’ve picked off the cream of the technical talent.

Yes, and they were all freelance. We brought people into Pinewood Studios who had never worked there before. Nobody argued. Nobody stopped us. Pinewood gave us the best they had, and when we needed other people we just brought them in. Except for the actors and associate producer Charles Greenlaw from Warner Bros., I was the only American on the entire project. I said earlier that Christopher Reeve was given to me by God, and so was Charlie Greenlaw, because there were a lot of problems on this film that had to do with the lack of knowledge about how to make it. What was needed was production knowledge and intelligence and observance of filmmaking procedures that had nothing to do with the special skills of the crew. So when Warners took an active interest and Charlie came over, that changed the whole aspect of the production.

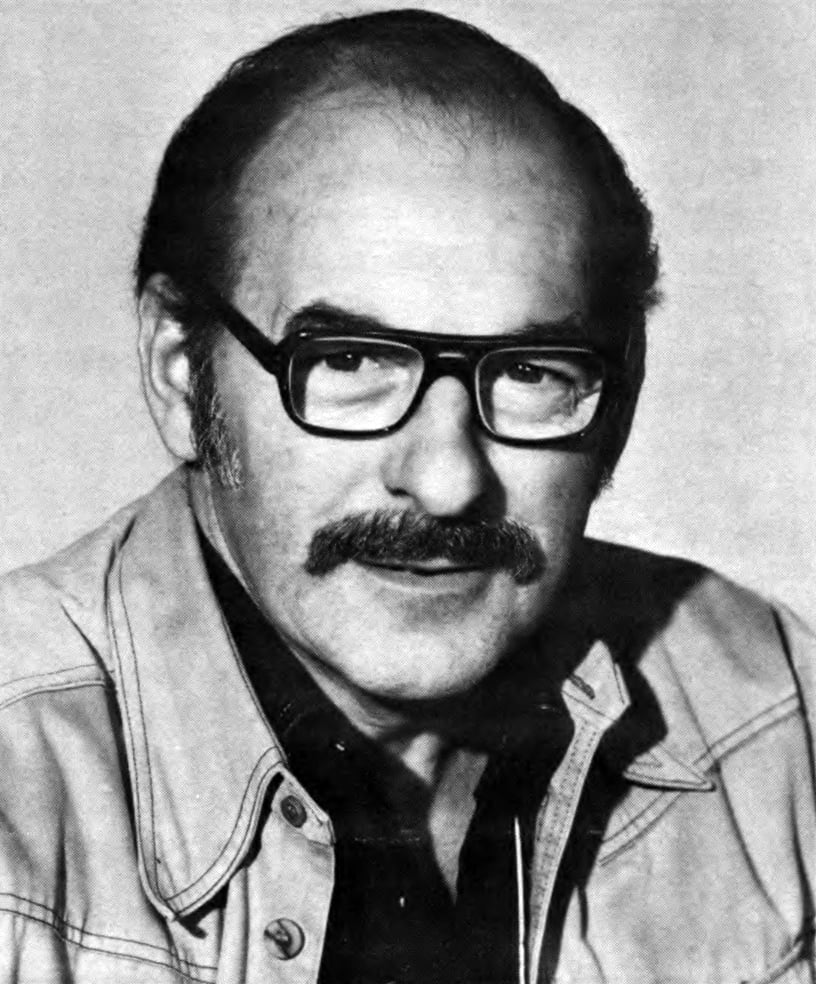

Geoffrey Unsworth was the director of photography on Superman. Does that mean that he did all the lighting except for the front projection and special effects sequences?

He did it all even though we had many cameramen on the picture. When we reached the point where we thought we were going to finish on a certain date, we gave Geoff the freedom to take another picture, which he did. Then I realized that I still had some things that I had to shoot. Geoff just hated to leave the company before the final shot, yet I could not offend the people he had taken the job with. But at that point, we had finished the major portion of the picture. Geoff did all of that, but we had other cameramen shooting in other units.

What was the most units you had shooting at any one time?

Six or seven in England and two in the States, but Geoffrey Unsworth saw everybody’s dailies, and we would ferry him in my little cart to the miniatures stage, to this stage, to that stage, while they were striking a set or doing something else. He would sit with each of the cameramen and give them that Geoff Unsworth input so that the whole picture has an overall look of Geoff. There was never the feeling of his infringement on anybody. They anticipated his visits, hoped for them, and were delighted when he came on the set to give his input. I ran his little legs off from stage to stage, and Geoff’s atmosphere, Geoff’s diffusions and Geoff’s desaturations are in all the shots. What you see on the screen in the final cut does not come from anybody else’s head but Geoffrey Unsworth’s.

You’ll find our complete report on the cinematographer’s work here.