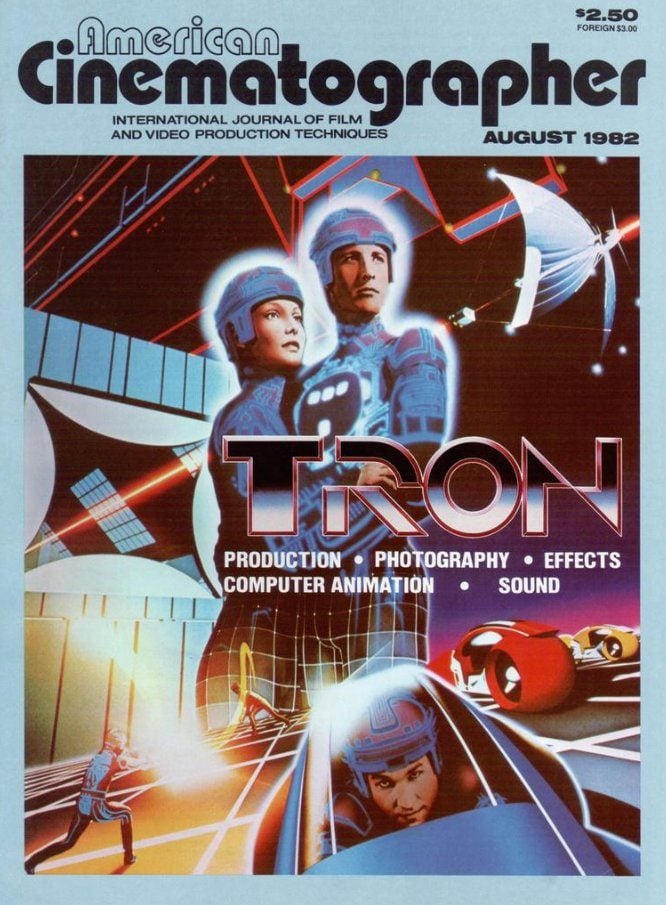

The Making of Tron

Bruce Logan, ASC and director Steven Lisberger take filmmaking into the computer realm, where programs are characters and video games are mortal combat.

Still images via ShotDeck.

“Computer technology is like photography. Photography alienates people with techo-talk about f-stops and ASA and before you know it you’ve got a whole clique; and everybody feels left out. Computers are really like that.”

Steven Lisberger is discussing the origins of Tron. “So when I saw video games for the first time, I thought, ‘These games are something I can relate to.’ I was fascinated by them, and I wanted to do a film. I was starting to think how I could do a film about this, and immediately—I mean that same instant that the idea came to me I realized that there were these techniques that would be very suitable for bringing video games and computer visuals to the screen. And that was the moment that the whole concept flashed across my mind.”

The techniques that Lisberger is referring to are backlit animation techniques he had been using in making commercials and educational films in Boston as well as computer animation techniques he had been keeping track of. At the time he was 26 and had been making animated films for four years. One of his first animated shorts had been nominated for a Student Academy Award, and he had done work for ABC and PBS. He received a $10,000 grant from the American Film Institute to do a six minute animated parody on the Olympics and then teamed up with Donald Kushner, an attorney and theatrical producer in Boston, to develop the idea into a feature length animated film for television. With funding from NBC, Kushner and Lisberger moved to the west coast to set up an animation studio in 1977, bringing with them a treatment for Tron.

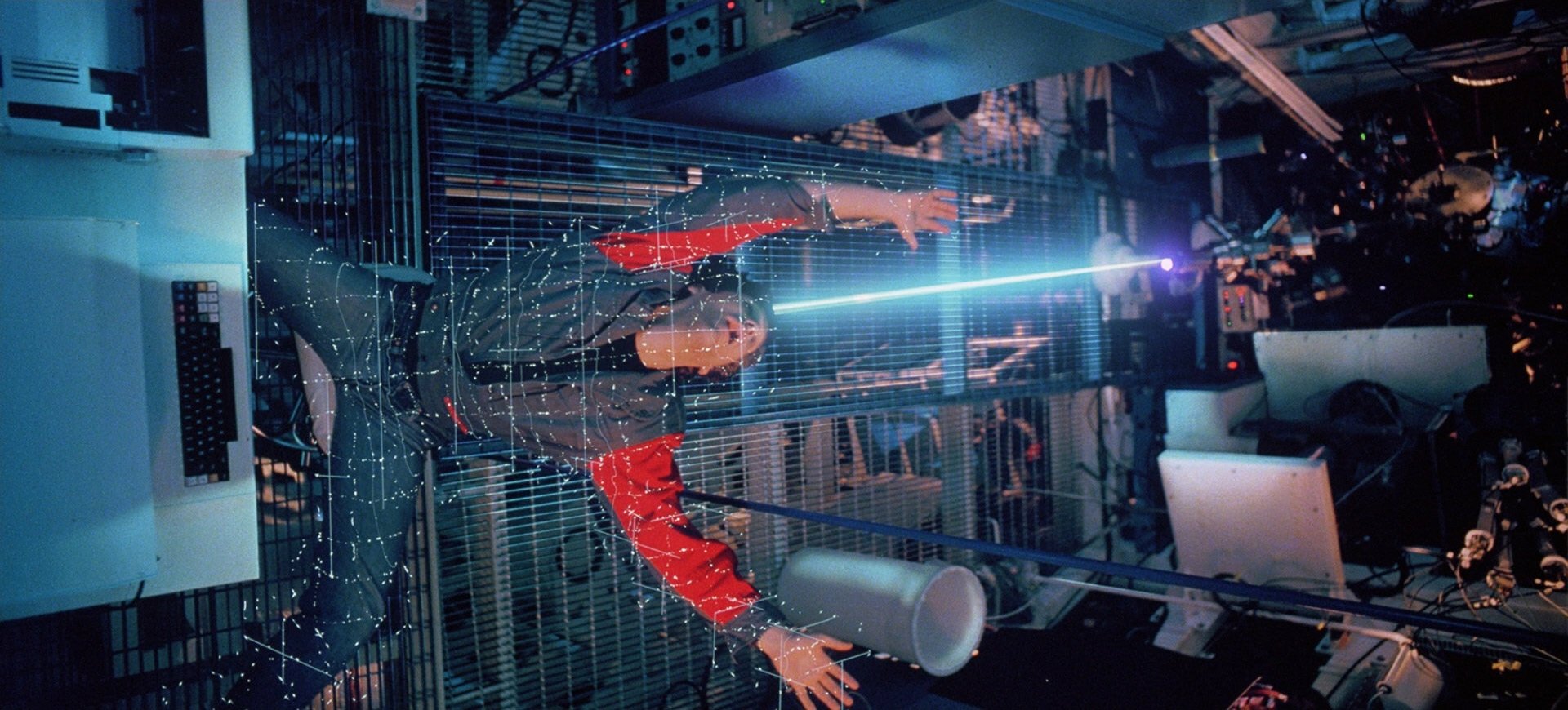

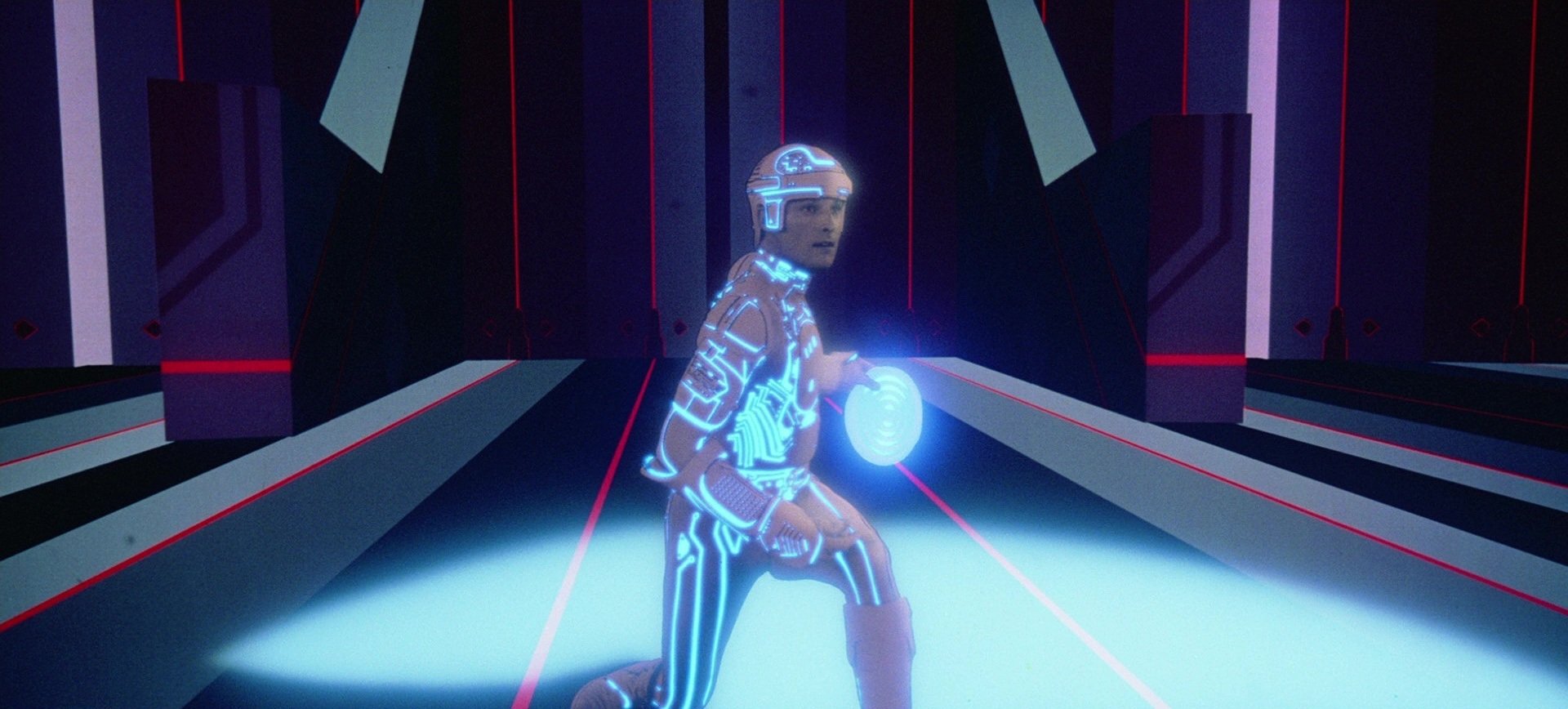

Tron is a story about a computer genius named Flynn (Jeff Bridges) who is trying to get the goods on an unscrupulous former boss, Dillinger (David Warner), by breaking into his computer system. In response, Dillinger's Master Control Program (MCP) blasts Flynn, digitizing him into an electronic counterpart of himself in a realm inside a computer, where the other programs are alter-egos of their programmers. There, the MCP's murderous henchman Sark (also played by Warner) is the counterpart of Flynn’s real life adversary Dillinger. Flynn is sentenced to die on the video game grid, and the bulk of the film depicts his struggle against the MCP with the aid of Tron, an electronic warrior (Bruce Boxleitner, who also plays Flynn's real-life programmer pal Alan Bradley), and other programs.

Developing Tron

Tron was originally conceived as predominantly an animated film. The story would be set up with live action and then once the hero entered the realm of the computer reality the visuals would become a combination of computer generated imagery and backlit animation. Lisberger and Kushner planned to do the film with independent financing, and one of the things Lisberger had been doing was talking to various computer image companies about techniques which could be used for sequences in the film. Lisberger recalls his early visits to companies like the Mathematic Applications Group Inc. (MAGI) and Information International Inc. (Triple-I) with amusement: “You gotta understand at this point I was really not connected to anything. It was that tenuous position where you’re going and telling these people that one day you really are going to do something with them, and they’re going, ‘Mm hmmm, sure you are.’ In the end I think they were more surprised than anybody that it actually occurred. I had been threatening them with all this work that I was going to bring them one day saying they better be ready; and they said, ‘Yeah, that should be the problem.’ And then it finally happened.”

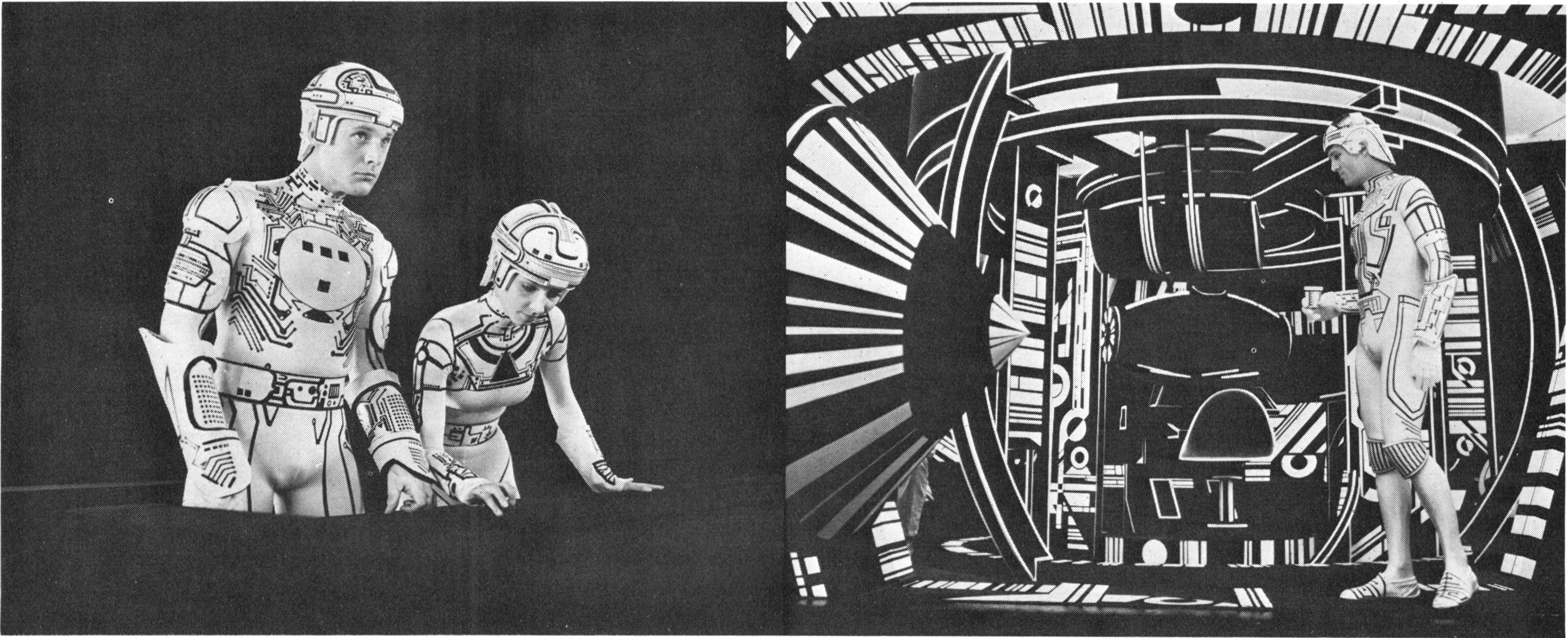

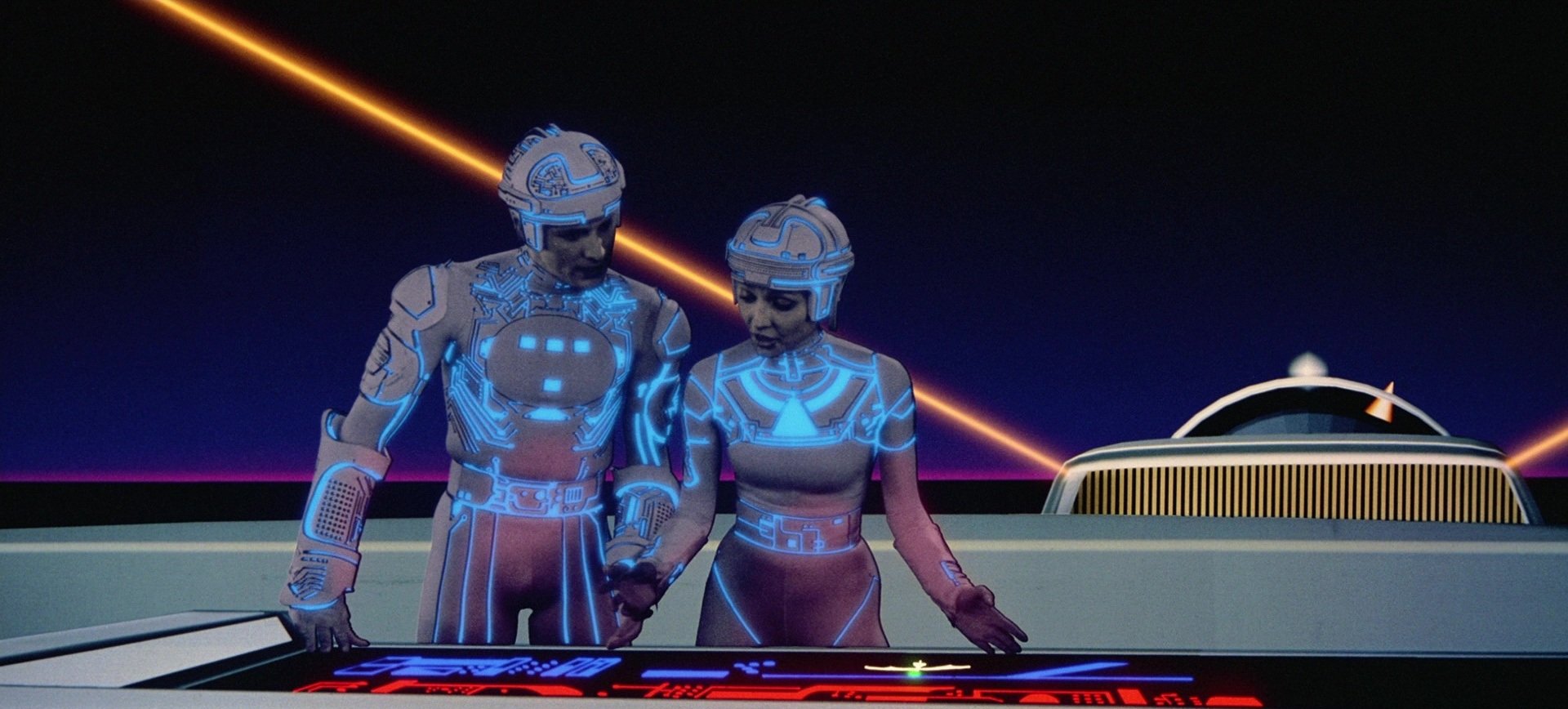

In his visits to Triple-I Lisberger met Richard Taylor, who had recently joined the company after six years with Robert Abel and Associates where he developed the famous “candy apple look” in television commercials. Discussions between Taylor and Lisberger gave birth to the idea of using live action photography as the basis for the backlit animation work in the electronic sequences. By shooting the actors in black-and white in some kind of limbo it would be possible to blow up each frame onto continuous tone and hi-con Kodaliths which could be used like animation cels in conjunction with other elements. Color would be introduced with back lighting and filters and the net result would be a visual style which was tied to the live action photography of the real world sequences and yet could be compatible with computer generated imagery to be used in portions of the electronic sequences. Lisberger did some tests with still frames to demonstrate the look that could be produced with this technique.

By this time Lisberger had already storyboarded the film completely with Bill Kroyer and Jerry Rees, two animators who had worked on Animalympics. Actually because of Lisberger’s own background in animation, the storyboarding was done hand in hand with the rewriting of the script. Every shot required for the film was represented by a drawing in the storyboards. Some computer animation tests had been done as well to demonstrate the feasibility of using computer generated imagery of a theatrical picture. All in all Kushner and Lisberger had put about $300,000 into the development of Tron. Efforts to secure $4 or $5 million in private backing reached a standstill even though a group of distributors was interested in funding the project, and Kushner and Lisberger decided to take the idea to Disney.

There was a new regime at Disney committed to embarking on more adventurous productions, but even they hesitated to go with both a first-time producer and a first-time director on a production based on techniques which had never been used extensively in features, if at all. The people at Disney also estimated that the film was more likely to cost $10 or $12 million. Eventually Disney agreed to finance a test reel with samples of computer generated footage from MAGI and Triple-I combined with some live action scenes designed to demonstrate exactly what the backlit composite effects would look like. There was apparently some skepticism as to whether the continuous tones could be preserved in the actor’s face as the image went through all the compositing stages. The test consisted of shots of a Frisbee champion throwing a Frisbee, since one of the weapons used in the electronic realm was to be a disc thrown like a Frisbee. The actor was dressed in a white costume with black lines on it and was photographed in a white limbo using both VistaVision and an anamorphic 35mm format. The footage was taken through the necessary duplicating and compositing stages to add glowing color to various elements and the results were successful enough to persuade Disney to finance the picture.

Designing Tron

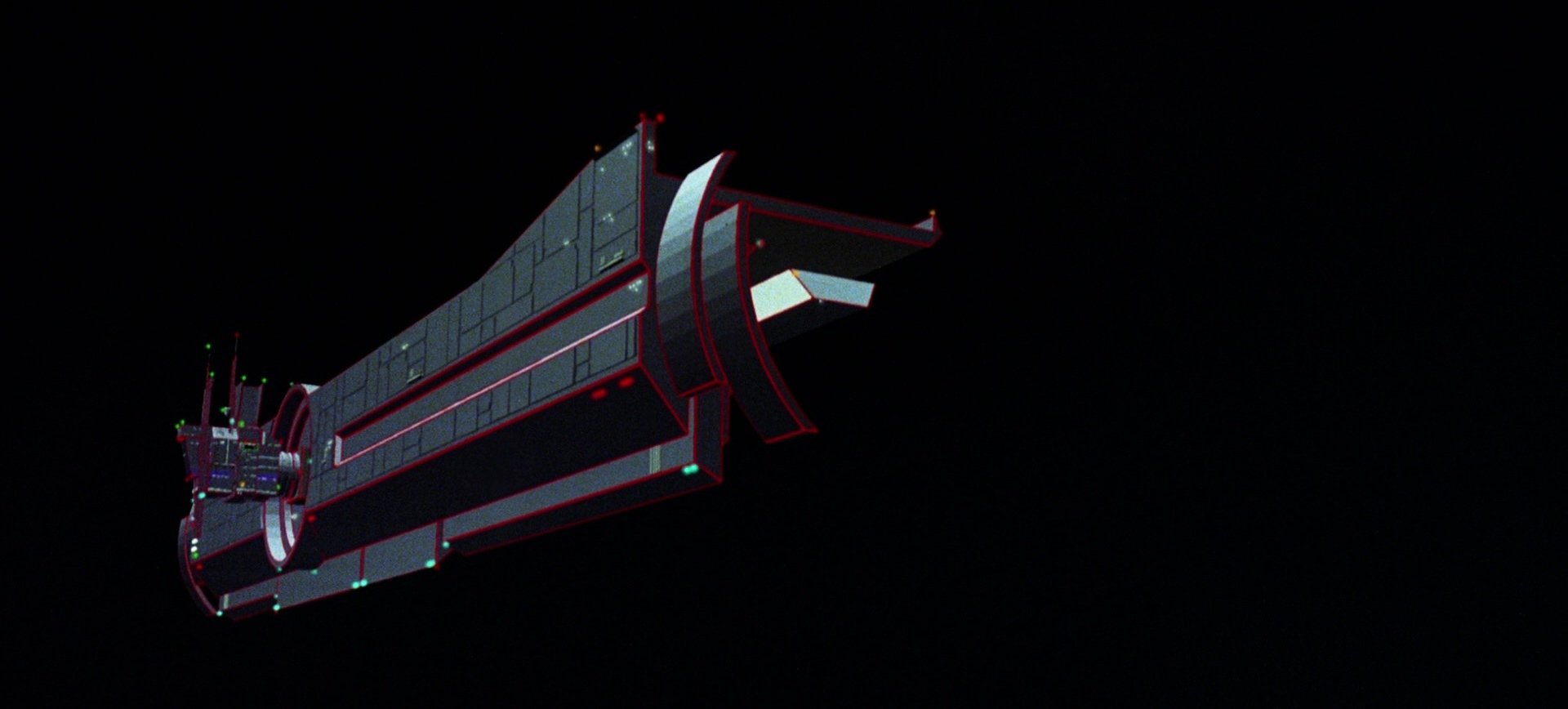

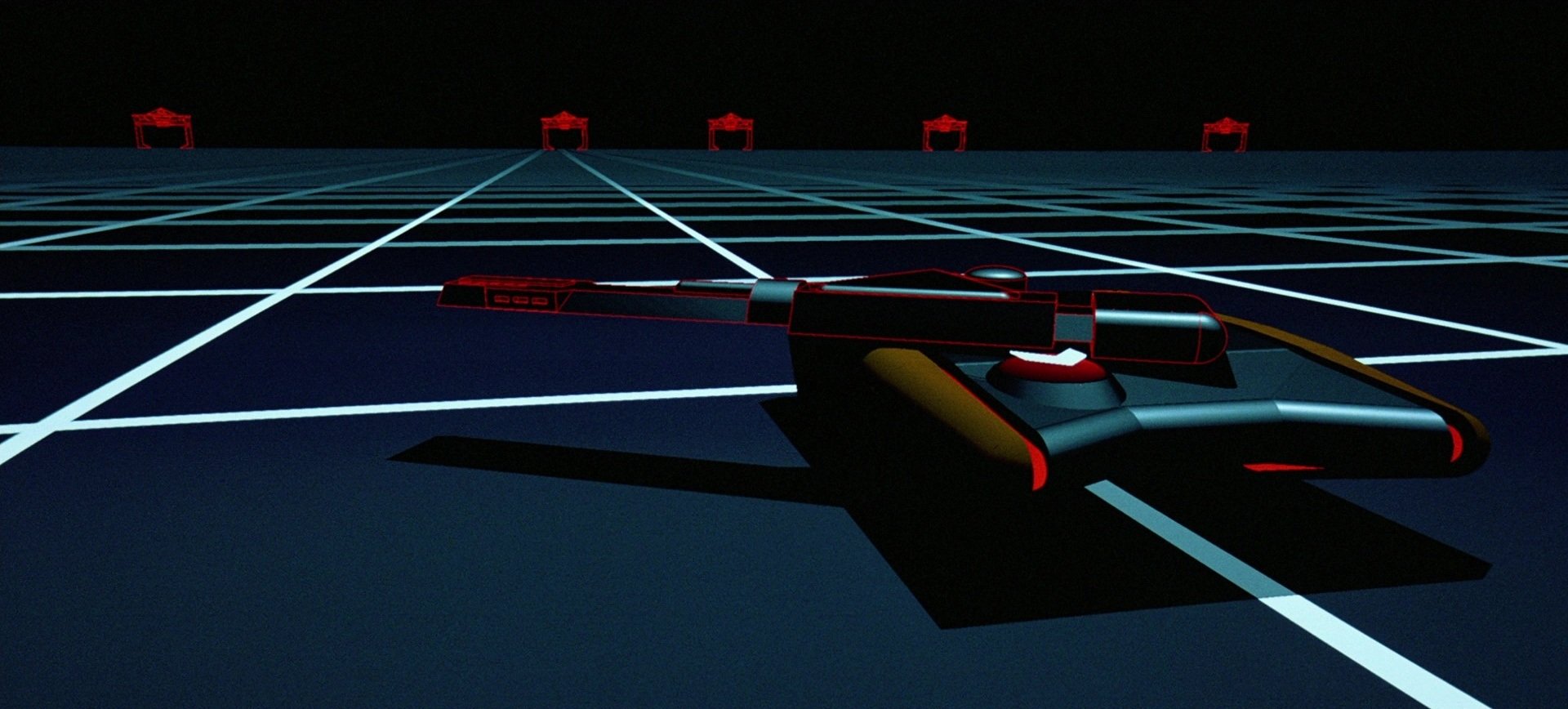

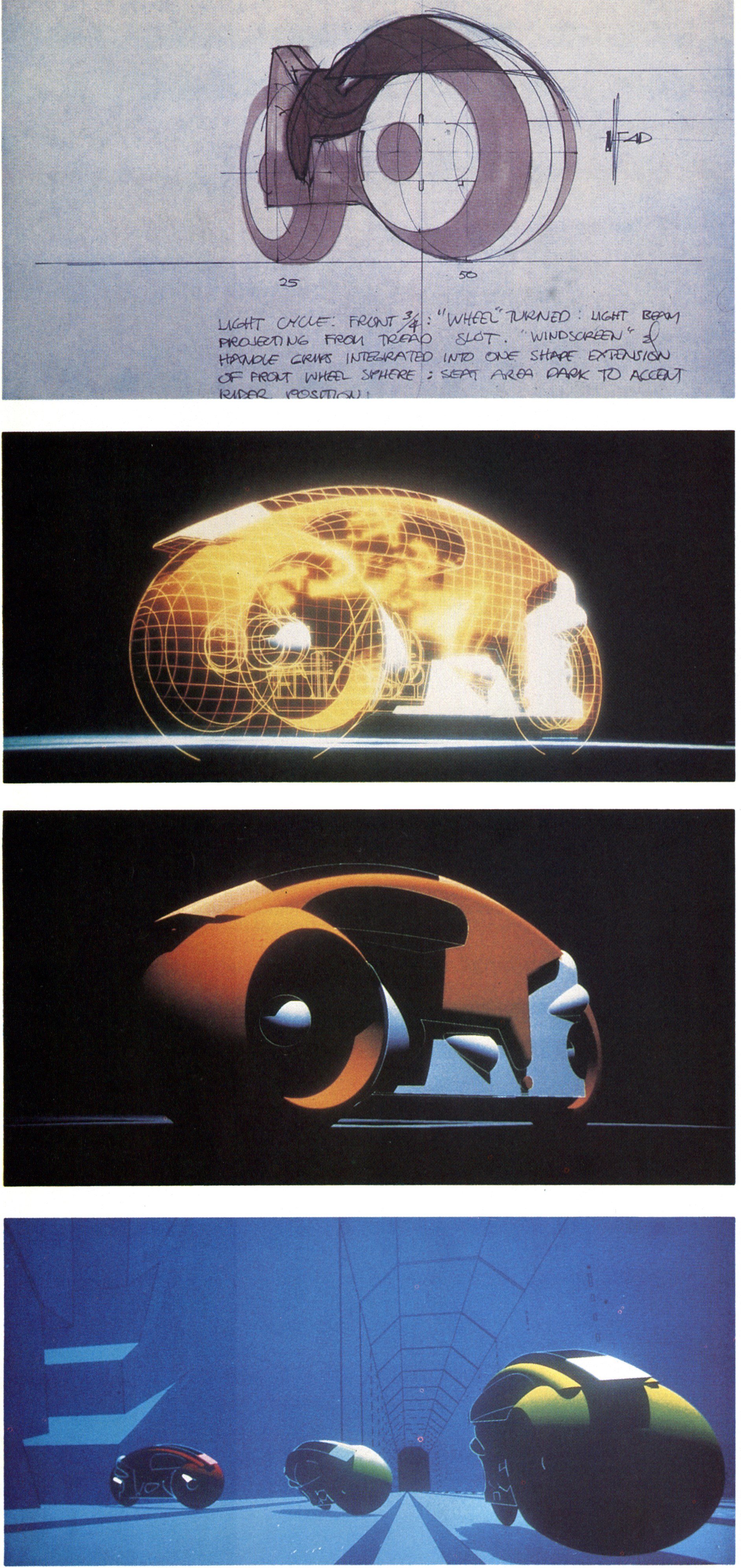

The script was rewritten and re-storyboarded with input from Disney, and three topflight designers were engaged to help design the look of the computer world: Moebius, Peter Lloyd, and Syd Mead. Moebius (Jean Giraud), known for his work in Heavy Metal magazine, was primarily responsible for the costume design. Peter Lloyd, a high tech commercial artist, designed environments; and Syd Mead, an internationally renowned industrial designer who had also done work on Star Trek: The Motion Picture and Blade Runner, concentrated primarily on the vehicles. He began by designing four vehicles which were to be generated by computer imagery: Sark’s command carrier, the light cycle, the tank and the solar sailer.

“Steve wanted recognizable symbols, so what I did was construct the actual article to start off. In the case of the aircraft carrier I drew an aircraft carrier the way they are now, the big Forrestal class carrier, profile, cross section, top view—just to get the sense of it in my mind as an object. And then gradually I started to play with the elements that make it recognizable as an aircraft carrier, which in that case is a flat deck with an offset conning tower kind of construction. I went after the gestalt of why an aircraft carrier looks like that to most people, the in-head memory of the audience, because that’s what you have to work with. You are stuck with that. If you violate that past a certain point you aren’t working with a real solution. And since Sark’s aircraft carrier floated in mid air I thought, ‘Well it doesn’t need a particular orientation.’ So really what I did was put two aircraft carriers edge to edge at the conning tower edge of the flight deck and move the flight deck 90° so that it stuck out rather than up. We had two flat planes at a right angle with a triangular connection on the back underside with the conning tower mass projecting out and floating in this great big round ring.”

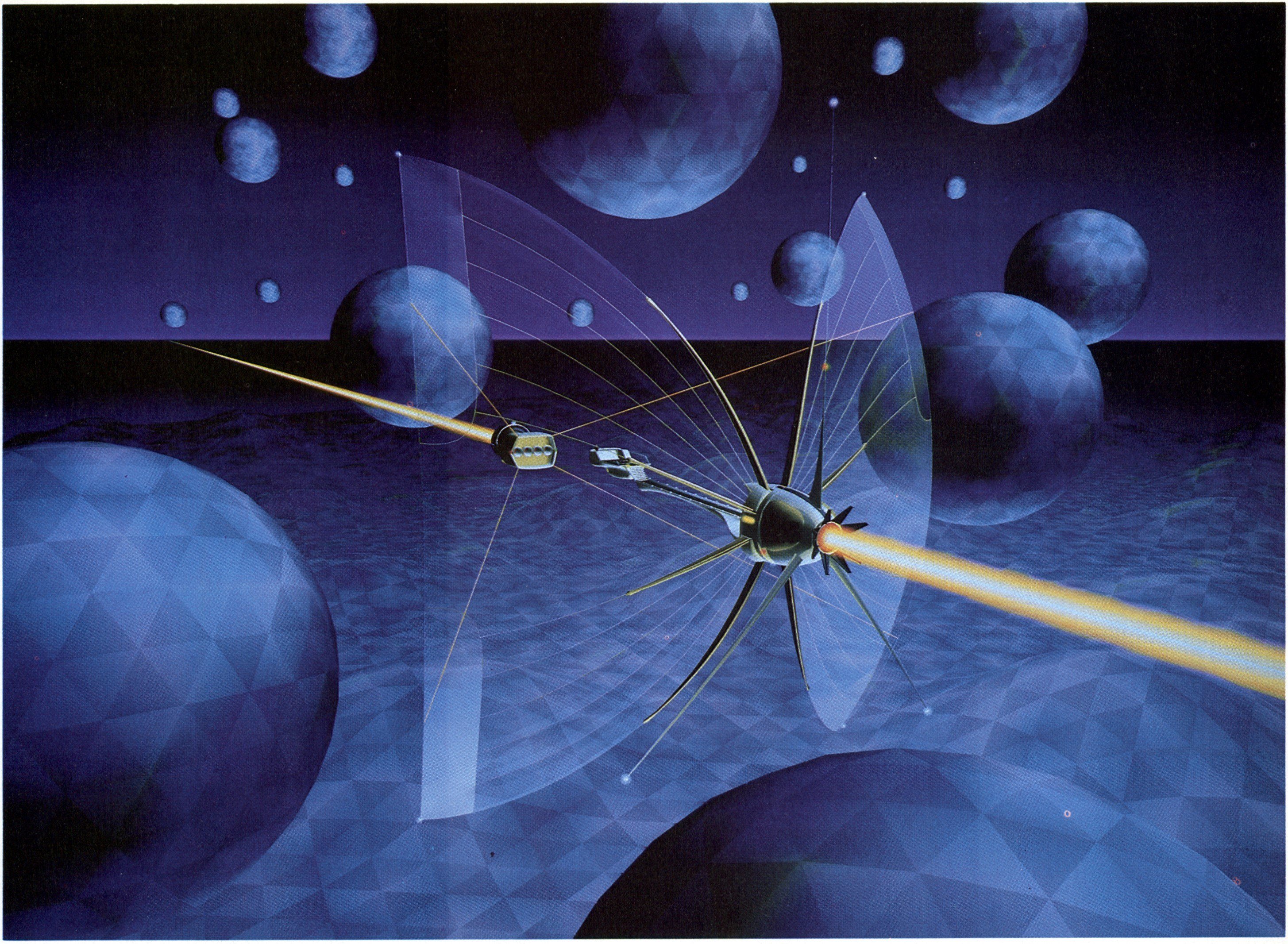

For the solar sailer Mead used a Spanish galleon as the starting point because he felt the description in the script had a kind of baroque sound to it. “The solar sailer started off as a Spanish galleon to capture the romantic aspects of a ship, so you have the poop deck on the one hand and the forecastle on the other with a sort of loop between. I gradually changed that into an organic fuselage and then took the sail on a shaft coming off the side with something like a tension plate with wires and riggings going back to a wobble so that you could manipulate the sail.

“Steve liked the design but thought the audience might orient the direction of travel with the sail position versus the gondola or the hull. So Moebius then took that particular object over and designed the solar sailer that is in the finished footage.” Mead similarly got involved in designing terrain and sets and the logo for the film after his initial work on the vehicles.

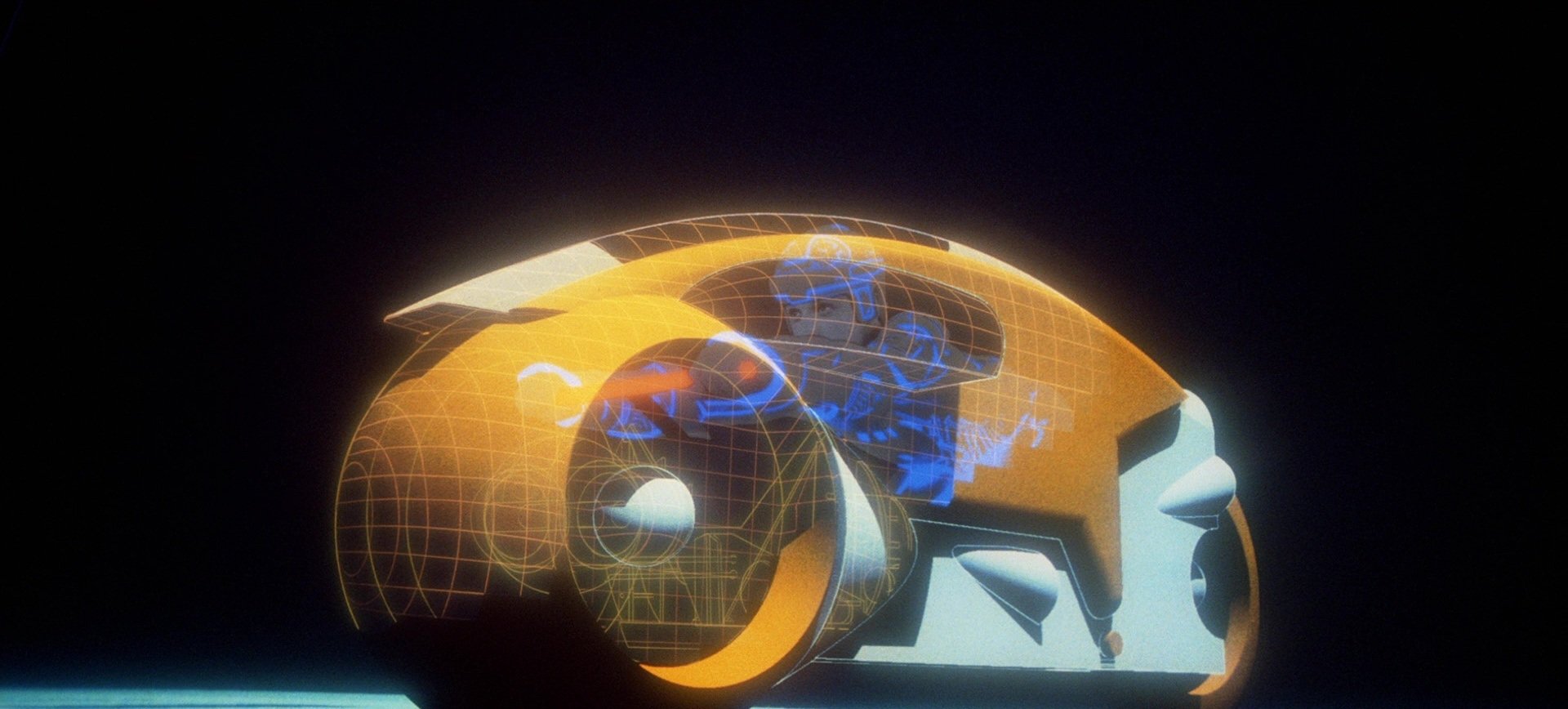

Although Mead was aware of the way in which the computer was used to construct its models of the objects, he did not really let that influence his designs too much. He was, in fact, surprised by the way some of his designs meshed with the computer programs. “The tank, which is a very complex object, was relatively cheap to produce in the computer memory whereas the light cycle, which is relatively simple — a round sphere with a blade construction — was very, very difficult and required a lot of compromises to make it look like it does in the finished footage.”

Designing objects and environments for hypothetical realm “inside” a computer required some way of indicating that the objects had a different kind of reality than physical objects in the “real” world. In addition to using the backlit effects to give everything an electrical glow, the principal means of achieving this was to have the objects “rez-up” and “de-rez.” The term is derived from “resolve” and refers to the way a computer image is generated. Generally the first step in the creation of a computer image is a form of line drawing displayed on a screen. As the image is fleshed out it is “resolved” into a solid looking image with colors and textures. So objects in the world of Tron appear as a set of vector lines or as a solid object depending on the amount of energy they have.

An object can be transported from one place to another by de-rezzing and then rezzing up in the new location. Characters cause the light cycles to rez up around them by pressing a button on the handlebar. Ironically, the effect of rezzing up or de-rezzing was not something that could be accomplished with computer imagery if the scene involved live action since there was no practical means of compositing live action with computer generated imagery used for anything other than a simple background. So when the light cycle rezzes up around an actor, the effect is achieved by conventional animation techniques.

Filming Tron

Budgeting the production was an extremely difficult task because no one had any experience making a feature in this manner. As Kushner puts it, budgeting live action photography is a science in comparison to budgeting a production of this sort. Even in retrospect it is difficult to evaluate the original budgets because the nature of the production changed as it progressed. In essence, the further into the production they went, the more opportunities they saw for improving the visual style of the film and the more committed everyone became to taking full advantage of those opportunities.

Fears about a directors guild strike and the commitment to a release date also put pressures on the production which increased the costs. Basically, however, no one had any way of anticipating the immensity of the post-production work required for the film. No one could foresee, for example, that it would be necessary to have over 200 people in Taiwan working 12 hours a day 7 days a week for four months inking cels.

The principal photography was originally scheduled for 50 days with no second unit. In the end it took 60 days with the last ten days being devoted to what Lisberger describes as essentially second unit work which he directed. Lisberger recalls, “I had to finish before the supposed directors strike, so we worked Saturdays and Sundays very often as well as we worked 14 or 16 hours a day. And then the strike never happened. The pace was pretty awesome. I would get up at 5:30, I was on the set about 7:00, and I rarely got home before 11:00 or 11:30. And I can remember going 14 days in a row and then getting one Sunday off and then going another 14 days in a row. All this on my first feature. If anybody ever tries to do a movie again in 70mm, have them give me a call before they start.”

One of the results of the test reel was the conclusion that is was absolutely essential to shoot the black-and-white live action footage on a large format negative because a 35mm anamorphic image just would not hold up well enough in the compositing process. The decision had been made to shoot all of the animation stand work and the computer generated imagery on VistaVision, and it was assumed that the live action photography would be done in VistaVision as well. The test was done in VistaVision but when director of photography Bruce Logan [ASC] got involved with the production he convinced Kushner and Lisberger that they would be better off shooting 65mm.

Logan’s job was complicated by the fact that he was not able to see a composited shot until after the completion of principal photography.

As he describes it, “From my experience on The Incredible Shrinking Woman I knew you couldn’t shoot a walking, talking motion picture in VistaVision. All the background plates on that picture were VistaVision, and they had dialogue in them so it necessitated having a VistaVision camera blimped, which is a 15 to 20 minute reload. We special ordered 2000’ rolls which the camera is designed to take, but unfortunately the clutches weren’t up to it so we ended up shooting 1000’ rolls which is five minutes of screen time in the VistaVision format.

Watch: A Look at the History and Inner Workings of the VistaVision Camera

“There’s only one blimp available, and it’s about 3 1/2’ or 4’ long and 3’ high and 3’ wide. It’s really an incredible device — all chrome hinges and leather padding. It looks like something out of an S and M shop. So 65mm seemed to be the way to go. I’d had a limited amount of experience just seeing [Super Panavision 70] being used on 2001, so I knew it actually worked even though it was a rackover system and had been on the shelf since Rhyan's Daughter.”

Logan experienced some difficulty in getting a 65mm camera properly tuned so that it didn’t chew up film, and it was hard to find an operator who had shot with a rackover viewfinder. The biggest problem however was getting enough light to shoot at the f-stop he needed to use. Because every frame of the black and white live action footage was going to be blown up onto Kodaliths and composited with other elements it had to be absolutely sharp. Not only was it necessary to stop down to get the maximum depth of field — a problem which was aggravated by the large negative format — but also it was necessary to cut down the shutter angle in order to prevent blurring of edges during movement.

Most of the black-and-white footage was shot with a 90° shutter. As a result Logan’s normal key light for the black and white scenes shot on the stage was around 1000 footcandles and at times he worked as high as 8,000 footcandles.

The post-production processes also required that the black-and-white images be flat and shadowless. The test had been shot with the actor in a white limbo to facilitate delineating the black vector lines on his costume from the background, but Logan quickly realized that it would be totally impractical to light all of the scenes in a white limbo and the decision was made to shoot all of the black-and-white scenes in a black limbo or with white vector lines on a black mock-up of a set. In that way it was not necessary to light everything in the frame.

Even so, it required a tremendous amount of current to provide thousands of footcandles of bounce light. At one point Logan was using 12,000 amps, and the City of Burbank called the studio to notify them that they would be shut down if they continued to draw so much current. Fortunately the studio was able to rearrange their load and work things out with the city so that Logan and his crew could resume shooting after about 45 minutes.

For the most part Logan lit the black-and-white scenes by bouncing maxi-brutes off 12'x12' sheets of white plastic ringed around the set and then when possible adding extra light on the actor’s face to give it some modeling. Because the environments were going to be added to the images in post-production, the sets on the stage consisted simply of shapes covered with black velvet or flocked paper. The shapes were constructed in accordance with dimensions which had been fed into the computer to create the background images and served to matte out the actor if he moved behind the object or wall.

Logan explains that it took a while to get used to working on this kind of set: “As the movie went on it became more and more apparent that we had all these black sets that gave us the spatial relationships as to how things would be so that we could black the scene out, but whenever we moved the lights around to a new set-up, it was like it was the same set-up every time. So finally we just built two of these lit areas at each end of the stage and put the sets down with tape on the floor and put the props in there the way they were going to be. We blocked the scene there and then just walked over to the lit area and put it in its correct orientation. For instance, Yori’s apartment had seven pieces of furniture in it. We blocked the scene the way we wanted to and then just measured all the distances from the lens to the couch to the side wall and transferred all that into our lit eye area.” [The scene in Yori's apartment was cut from the final film.]

Another approach that evolved during the production was to minimize the set and the set dressing. Originally, a relatively full set was constructed and covered with black so that the actors would be automatically matted out of the shot as they interacted with the set. Often the set pieces made it difficult to keep the light flat enough on the actors’ faces. Logan was constantly hiding lights among and even inside the black set pieces in order to remove a shadow.

It was felt that in order to facilitate separating the faces from the vector lines and the background, it was necessary to keep the continuous tone portion of the image within a 2 1/2-stop range. If an actor moved near a wall which blocked a significant portion of the light from his face, it would be necessary to hide a light somewhere in the set to fill his face in that position. Eventually they resorted to removing all except the edge of the wall on the assumption that the edge was all that was required to create the matte line. The rest could be blocked out in prepping the Kodaliths to be re-photographed.

In some cases, however, it was essential to include the entire set as a reference for the background artists. After every setup Logan would shoot an overexposed frame in which the shapes of the set pieces would be visible and which could serve as a guide for the background artist. Even with the extreme light levels there were still problems with depth of field. “I hate to say it,” confides Lisberger, “but in certain scenes we actually were reduced to putting C-stands up people’s shirt backs to make sure that they knew exactly where their marks were! The depth of field was so critical we were talking about half an inch, and that gets a little weird trying to play an intimate scene with a C-stand up your back. We would usually have a camera assistant with a telescopic sight with a cross-hair, and he would tell me through hand signals whether the actor was drifting ahead or behind the mark, and I would then, through hand signals, try to help the actor regain his mark, all the while giving his Academy Award winning performance.”

Logan’s job was complicated by the fact that he was not able to see a composited shot until after the completion of principal photography. He didn’t even see any of the black-and-white footage he was shooting for the first three weeks.

Since shooting 65mm [Eastman] Double-X is not exactly an everyday occurrence in Hollywood, Hal Mann Laboratory had to install special equipment to handle the footage, and the processing system was not completely perfected until three weeks into production. Once the footage began to be processed it was possible to make wedge tests, but even with wedge tests it was difficult to be certain about how critical the light levels and depth of field were.

To some extent Logan found himself relying on Lisberger’s experience as an animator to decide whether, for example, it was necessary to use a 45° shutter angle to ensure clean edges in a particular shot. Sometimes when he would have to double the light level to shoot with a 45° shutter instead of a 90° shutter, Logan might have thought that Lisberger was being overly concerned with the possibility that some portion of the image might smear and not reproduce properly on the Kodalith. In retrospect, however, he concedes that Lisberger was right and thinks that it might have even been advisable to use a 22 1/2° shutter angle for shots involving very fast movement.

The actors wore white costumes with black lines on them that needed to reproduce cleanly in order to add the glowing vector lines. With rapid movement the black lines would tend to smear and register as gray instead of black, and if the gray were above a certain density on the negative, it would not be picked up in the Kodalith. The net result would be that the vector line would simply disappear during the motion.

On the other hand Logan concluded that they may have been overly conservative in their concerns about depth of field and the latitude of the continuous tone portions of the images. “We did these two sequences in the movie —the recognizer head and the interior of the tank — in which we actually found out that a lot of our fears were just out the window. Admittedly they were very confined circumstances, but the light actually fell off towards the vector line exposure and things were out of focus and yet they turned out to be some of the most spectacular stuff in the movie.”

For full access to the rest of this story and the American Cinematographer archive, which includes more than 105 years of essential motion-picture production coverage, become a subscriber today.