A Movie Under Siege: The Offer

Salvatore Totino, ASC, AIC re-creates ’70s Hollywood and New York to dramatize the making of The Godfather.

Salvatore Totino, ASC, AIC re-creates ’70s Hollywood and New York to dramatize the making of The Godfather.

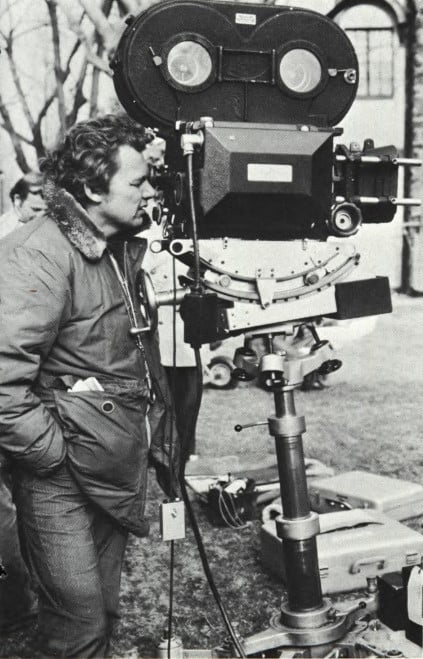

Francis Ford Coppola (Dan Fogler).

Much has been written about the impact director Francis Ford Coppola’s 1972 feature The Godfather has had on popular culture, and how the work of Gordon Willis, ASC has inspired many cinematographers who followed. So, when Salvatore Totino, ASC, AIC was approached to shoot the Paramount Plus miniseries The Offer, which delves into the drama surrounding the movie’s contentious production, he simply couldn’t refuse.

“The Godfather is probably one of the top-five best-directed, best-shot and best-acted movies of the last century,” says Totino, whose feature credits include Spider-Man: Homecoming, Everest (AC Oct. ’15), The Da Vinci Code (AC June ’06) and Cinderella Man (AC June ’05). “I saw it when I was 10, and it’s been influential on my life as a filmmaker. It’s not only about the cinematography — it’s the whole experience. There are so many nuances in the film; you can watch it over and over again and still see more.”

Prior to starting The Offer, director Dexter Fletcher, who helmed the first two of the show’s 10 episodes, contacted Totino’s agent, who recommended the cinematographer for the gig. “I read the scripts for the first few episodes, and I was really interested in the behind-the-scenes story,” Totino continues. “I did a little digging and found out that much of it was actually true. It’s film history, and it’s fascinating, so I said I would love to be part of the project.”

The Offer arrives as The Godfather marks its 50th anniversary this year. The miniseries is told from the perspective of the film’s producer, Albert S. Ruddy (Miles Teller), who has no idea what he’s in for when he signs on to make an adaptation of Mario Puzo’s bestselling novel, an epic saga about the transfer of power in an Italian-American gangster family during the ’40s and ’50s.

Ribisi) rails against the ethnic stereotyping the community has perceived in Mario Puzo’s bestselling novel.

Real-life New York crime boss Joseph Colombo (Giovanni Ribisi), who created the Italian-American Civil Rights League, leads the charge against the film’s production, arguing that the story perpetuates harmful Italian stereotypes. Ruddy meets with Colombo and wins him over by promising to excise the terms “Mafia” and “Cosa Nostra” from the script, but soon finds himself becoming uncomfortably enmeshed in mob machinations.

Meanwhile, in Hollywood, The Godfather becomes a source of conflict at Paramount Pictures. While Coppola (Dan Fogler) fights to realize his vision for the film, Paramount’s mercurial head of production, Robert Evans (Matthew Goode), clashes with Charles Bluhdorn (Burn Gorman), the Austrian-born industrialist owner of the studio’s parent company, Gulf and Western. Evans also locks horns with fictional executive Barry Lapidus (Colin Hanks), who cares less about film art than bottom-line financial success.

When Totino and Fletcher sat down to map out their visual strategy for the series, the main order of business was establishing distinct looks for Los Angeles, where the Paramount offices are located, and New York, where The Godfather was primarily filmed and where the Colombo crime family and their rivals were based. “I wanted L.A. to be that warm, sunny, inviting place everybody from the East Coast always dreams of going to,” Totino says. “Then there’s the dark and heavy side of New York, where I grew up on the periphery of that Mafia world. I was trying to keep those scenes cool, with more contrast and blue in the shadows, whereas in L.A. the look is more comforting.”

Coppola, despite the mob’s interference, ultimately got to shoot his New York scenes in the actual city and various boroughs, but the filmmakers behind The Offer had to re-create the Big Apple in Hollywood on the Paramount, Universal and Warner Bros. backlots. “When you’re shooting in New York, tall buildings create a lot of shade with pockets of sunlight,” Totino notes. “You have a lot of coolness and shadows, but also warmth in the highlights. That was a challenge on the backlots, where you put up greenscreens but you’re not getting the shadows that would emulate New York.”

To help determine the best times of day to shoot exterior scenes with the appropriate shadow and sunlight, Totino used SunPath software to predetermine the sun’s position. Key grip John Miller assisted by positioning a couple of fly swatters with 20' x 20' solids in the best spots to create the desired shadows.

For interior scenes on any of his shoots, Totino thinks first and foremost about lighting the environment, relying on sources coming through windows for a natural look and then tweaking them to suggest different moods and times of day.

On The Offer, good results were occasionally achieved by happenstance. One example is an early sequence set in Evans’ spacious office, which production designer Laurence Bennett and his team decorated with dark furniture, parquet flooring, beige walls adorned with framed movie posters, and a window with vertical blinds revealing a Translite of a neighboring building on the Paramount lot.

left) collaborates with Coppola on the movie’s screenplay.

Throughout the series, the honcho’s office provides the backdrop for plenty of sparring, studio politicking and drinking. As the crew prepared to shoot on the set, an Arri Studio T12 Fresnel stood in an arbitrary position behind a tree that had been placed outside a window; when the crew turned it on just to provide a temporary work light, Totino found that the light’s angle was perfect for the scene. “The placement made it look like late-afternoon sun,” he explains. “It’s like you’re on vacation, it’s five o’clock, you’ve had a couple of drinks — and you’re laying by the pool a little fuzzy — when you see warm sunlight peek through the trees and create little shadows. That’s what it felt like, and I just went with it.”

When skylight was desired, trusses were set up outside the room to position Arri SkyPanel S360-C units; fill and eyelight were provided from the floor with Astera Titan tubes diffused with Magic Cloth in Snapbags.

Departing from the “Godfather Look”

Totino shot with Sony Venice cameras in 4K RAW format, which he used for the first time while shooting the forthcoming sci-fi thriller 65. Totino notes that he and Fletcher did not set out to imitate Willis’ work on The Godfather, which was shot partly on spherical Super Baltar lenses and became famous for the cinematographer’s inventive use of top light as a consistent motif throughout the picture. “There wasn’t any talk about [emulating the ‘Godfather look’], nor did I feel it would be the right approach,” Totino says. “I wanted to shoot the film in the anamorphic format with Hawk V-Lite lenses, which I also used on 65. I love them because I like things to be a little ‘off’ sometimes. I love the quick falloff in depth of field, and I embraced shooting with V-Lites more wide-open so that there would be softness and banding on the edges, which creates flare and makes the light react in different ways.”

Totino shot mostly at T3 on a 45mm lens, calling upon a 65mm for close-ups and a 28mm when the filmmakers wanted to go very wide.

Even in later episodes, when actors from The Godfather are introduced and the movie’s production begins, Totino and his directors remained true to their naturalistic approach — although there are some moments when The Offer references the original film’s moody and then-controversial style. This style almost got Willis fired, which is depicted in the miniseries as well. Coppola is initially unhappy with the dark lighting fashioned by Willis (T.J. Thyne), arguing that the audience can’t relate to the characters if they can’t see their eyes, but eventually decides that he loves the style. (In real life, Coppola and Willis did clash over various creative strategies, but the director came to appreciate Willis’ artistry and vigorously defended his director of photography against the studio’s execs, who took issue with the cinematographer’s sepulchral imagery for some of the reasons cited in the show.)

Willis notoriously preferred actors to hit their marks on stage — especially when the very sculpted lighting he designed on set was intended to illuminate their particular physical features, or specific aspects of their performances. But Totino is fine with actors moving in and out of the light. “That’s what it’s like when you sit in your house during the day without lights on,” he says. “Light comes through the windows, and some parts of the room are dark, and some are light. I’m a big fan of Renaissance paintings, where there are a lot of those [kinds of] shadows, so I try to approach things that way.” Like Willis, however, he also appreciates a bit of artful darkness applied in the frame, or obscuring faces. “Sometimes the actors’ faces are in the dark, and I’ll often joke and tell them, ‘Make sure you speak louder, so at least we can hear you.’”

One of the key New York sets in The Offer is Little Italy’s Ravenite Social Club, where Carlo Gambino (Anthony Skordi), who presides over all the major Italian-American crime families, holds court. The front room — with its tables and chairs, wood wainscoting, and tiled floors — is a dark space with few windows and doors, but areas deeper in the room are lit by practical hanging lamps and wall sconces. “In Little Italy, there are tenement buildings five or six stories high on either side of the street, so not a lot of sunlight would come in,” Totino notes. “It’s more of a soft light produced by sunlight bouncing off other buildings. For daytime shots, I would use a warmer light, and I’d apply cooler light for night or if the scene called for an overcast day.”

Gaffer John Vecchio adds, “We used banks of Mole Par Cans on a truss positioned outside the front window to bounce light down off the mosaic tile floor. We also used 12K Tungsten Pars aimed through the yellow glass at the back of the club. Our New York scenes had more bounced floor light, and for L.A. scenes, we used more direct sun.”

On many of the sets, the crew made efficient use of varied light fixtures — combining the illumination from units built into the sets with lights positioned on trusses outside, including a 10K Fresnel for hard sun and SkyPanel S360-C units for a skylight look. “That way,” Vecchio says, “lighting programmer Chris Chalk could switch back and forth between [the looks], and we could go one way or another quickly. Rigging gaffer Victor Mendoza did an amazing job with his crew.”

cocktails in the Paramount dining room.

These pre-rigged sets helped maintain a consistent style throughout the season. Vecchio adds, “Victor and Chris gave us a lot of control over the sets through the lighting board, so we could do multiple episodes and change up the look [as new directors came in].” The rotation of directors included Adam Arkin (Episodes 3, 4, 9 and 10), Colin Bucksey (5 and 6) and Gwyneth Horder-Payton (7 and 8). Totino left after Episode 6 to collaborate with Fletcher on his feature, Ghosted. Cinematographer Elie Smolkin, CSC shot the remaining four episodes.

Totino says the other directors he worked with, Arkin and Bucksey, wanted to honor what he and Fletcher had set up. “They didn’t want to change the look,” he says. “They wanted to help tell a story and come up with ideas that elevated scenes. I explained my rules and how I was approaching the project, and they said, ‘Let’s work within that. Here are some of my ideas, [now] how can we make it all work?’”

For example, in Episode 3 (“Fade In”), Gambino convenes a meeting with Colombo and other family heads to discuss the troubling news that “Crazy” Joe Gallo (Joseph Russo) — an unhinged mobster with a beef against Colombo — has been released from prison. Arkin asked Totino if they could shoot the scene in a circular movement that would follow the dialogue among the seated characters. “To do that, you have to be able to get to each actor as they start their lines, which is tricky, especially when you don’t have the same amount of time to rehearse that you would on a film,” Totino says. “We had two hours to do the scene, and we did a couple of rehearsals so operator Kris Krosskove and I could figure out the timing. We made a dance floor and wound up doing the scene that way, and it came out fantastic.”

As he prepared to leave the series, Totino recommended Smolkin to handle the remaining episodes. “I advised him a few times on how I was doing things, and he got it,” Totino says. “It’s not like when I’ve come onto a feature to do some additional photography because the original cinematographer wasn’t available. At that point, you’re doing shots within a scene, and you have to do everything exactly how the other DP did it. On The Offer, Elie followed our general rules, but he also put his own stamp on it, and I support him on that.”

2.39:1

Cameras: Sony Venice

Lenses: Hawk V-Lite anamorphic

Turmoil — and Top Light — on The Godfather

The late Gordon Willis, ASC is so revered for the cinematography he brought to The Godfather that his work prompted a fellow DP, Tom McDonough, to refer to the film in his memoir as “the Sistine Chapel of cinematography.”

Although Willis himself clearly recognized that the picture would forever be regarded as an immortal screen classic, he was reflexively unpretentious and always accepted such lavish praise with humility. He was fond of pointing out that that Paramount Pictures’ initial plans for the movie — as depicted in The Offer — were relatively modest in scope, and that the studio “was just looking to make an inexpensive mob movie.”

However, once Willis signed on the shoot The Godfather, he discovered that the project’s 32-year-old director, Francis Ford Coppola, had more ambitious ideas for the material. Coppola envisioned the saga of the Corleone clan as an epic take on Shakespeare’s King Lear — a familial drama of operatic proportions that would explore an array of meaty themes, including loyalty, betrayal, and the corrosive effect of absolute power.

The director would ultimately achieve many of his grand plans, but the sweeping scope of his vision complicated the production’s requirements and led him into run-ins with the Paramount brass and members of his own crew, including Willis. Coppola was nearly fired on several occasions, but somehow survived the process to produce a truly great film filled with memorable dialogue and spectacular set pieces.

While many real-life figures associated with The Godfather have complained that The Offer takes creative liberties with the story of the movie’s production, Willis always said that shooting the gangster opus was no picnic. “The movie was full of turmoil, and there were a lot of fights and confrontations,” he described. “Francis was under a lot of pressure from Paramount, because he wasn’t really in a position yet to dictate his own terms. The movie was very difficult in that respect, because it was hard for him to function, which made it hard for everyone else to function. The situation was very tenuous at the management level, and it didn’t work very well for anybody. But to Francis’s credit, he never gave up — he hung in there.”

Willis noted that a now-legendary screen test of star Marlon Brando — whose casting the studio opposed — with providing the inspiration for the now-famous, brooding top-light style he fashioned for The Godfather. Just 47 years old at the time, Brando transformed himself into an aging mobster by blackening his hair with shoe polish, applying a fake moustache, cramming Kleenex tissues into his cheeks, and speaking with a mumble. His performance was so spectacularly convincing that the Paramount brass was compelled to relent. “I remember shooting the tests of Brando,” Willis said. “We put him at a table, and I used overhead lighting to make his makeup work. That’s how that whole lighting strategy evolved: Sometimes you make decisions in order to make a particular character or setting work. In retrospect, you can romanticize your reasons for doing something, but the bottom line is that I made a decision to light Marlon in a manner that would define his character. Of course, I also had to make the whole movie work that way. The choice was, ‘Okay, I think this lighting will work really well for him, and it will work for the movie.’ Overhead lighting was not a new idea, but it was a new idea to extend it for an entire movie, on everyone and everything. The basis for that approach, though, was to fashion Marlon into Don Corleone.” — Stephen Pizzello