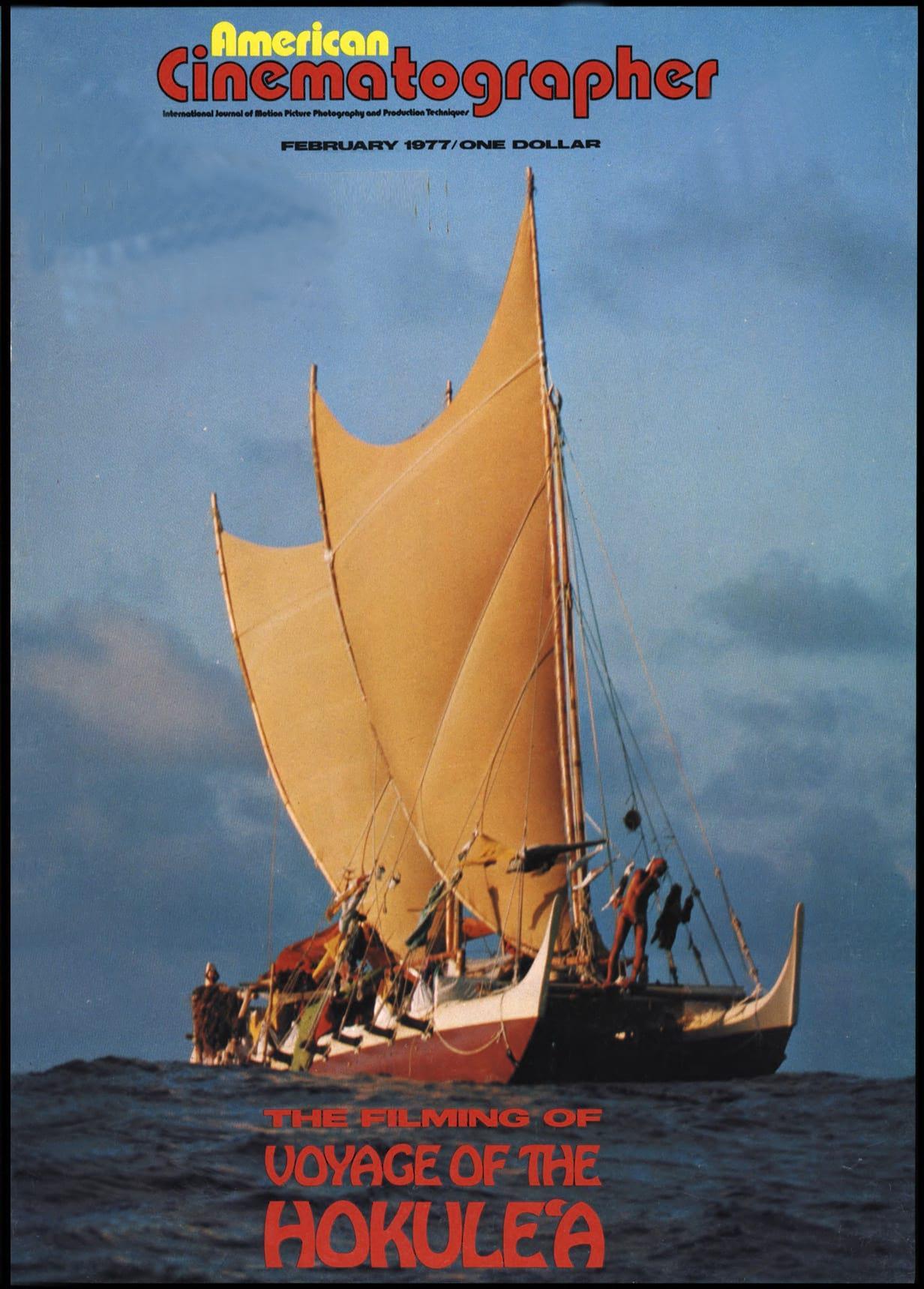

The Photography of Rocky

This low-budget feature about an over-the-hill boxer — which has become the “sleeper” hit of the year — offered exciting action and several stimulating cinematographic challenges.

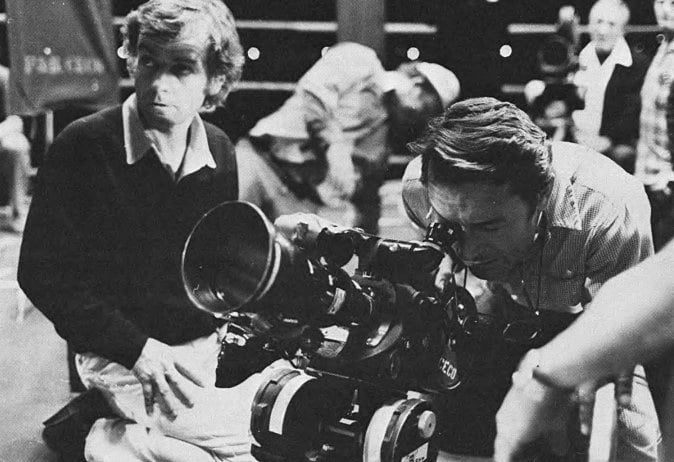

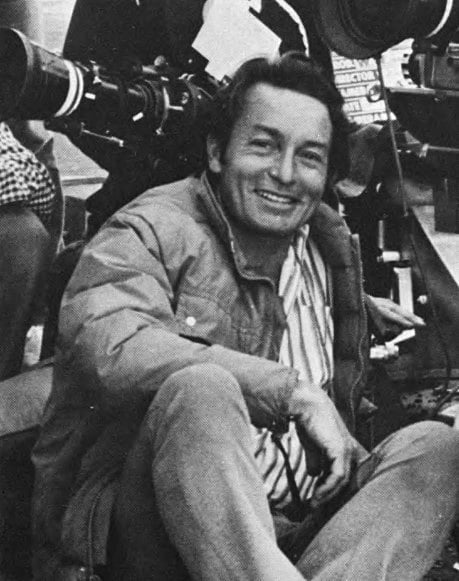

I was first contacted about photographing Rocky by director John G. Avildsen, with whom I had worked before on Save The Tiger and W.W. and The Dixie Dancekings. “We’ve got a fight picture,” he told me. “It’s sort of like an old-fashioned movie.” Both of those elements appealed to me.

I think everyone knows by now that Chartoff-Winkler produced the picture and sort of went into hock by mortgaging their homes in order to complete it, but Sylvester Stallone, of course, was the real genius behind the project.

When I first met with Sylvester and John we talked about the picture and went down to the Olympic Auditorium to watch some boxing matches, just to get an idea of what boxing was like. Neither John nor I had been very much into that kind of thing. It became obvious that our biggest problems would have to do with the big crowd scenes, the fight itself — how it would have to be choreographed so that it could be filmed.

Very often — and this has consistently been the case with the pictures I’ve been involved in — the cameraman reads the script and visualizes it in his own mind as a certain series of images. But I sometimes wonder if all that homework is worth the time it takes, because quite often when you get to doing it (unless it’s a big production that can be story-boarded), you find that the ideas you formulated when you first read the script simply won’t work, because the reality of the situation is totally different.

I don’t know what the actual budget was on Rocky, but it was very much of a budget-conscious picture. We really weren’t aware of its potential success or that it would take off the way it did until we were halfway through the picture. Then it became evident to everyone that this really would be a “sleeper” picture.

The locale of Rocky is Philadelphia and everyone thinks the picture was made on the East Coast. In reality, most of it was shot in Hollywood, but when I came onto the picture, John Avildsen, who is a cameraman himself, informed me that they had already shot about eight days of footage in Philadelphia. My first connection with the picture was the photography that was done in Los Angeles.

John is a low-keyed director and, being a naturalist, he has a preference for photography that has a kind of natural look. A lot of the people he used on Save The Tiger were also on the crew of this picture, so it was a happy kind of group — a crew that John felt comfortable with. He is after all, a film-maker of the kind of shoot-it-and-cut-it-yourself variety, so when he comes to Hollywood and gets involved in one of those things where there are a hundred trucks and honey wagons and so forth he tends to stand off a bit.

Our shooting schedule was seven weeks, but the picture came in under that time. We used the 5247 negative throughout without any special manipulating techniques, except that we pushed all of the interiors one stop, which is not uncommon.

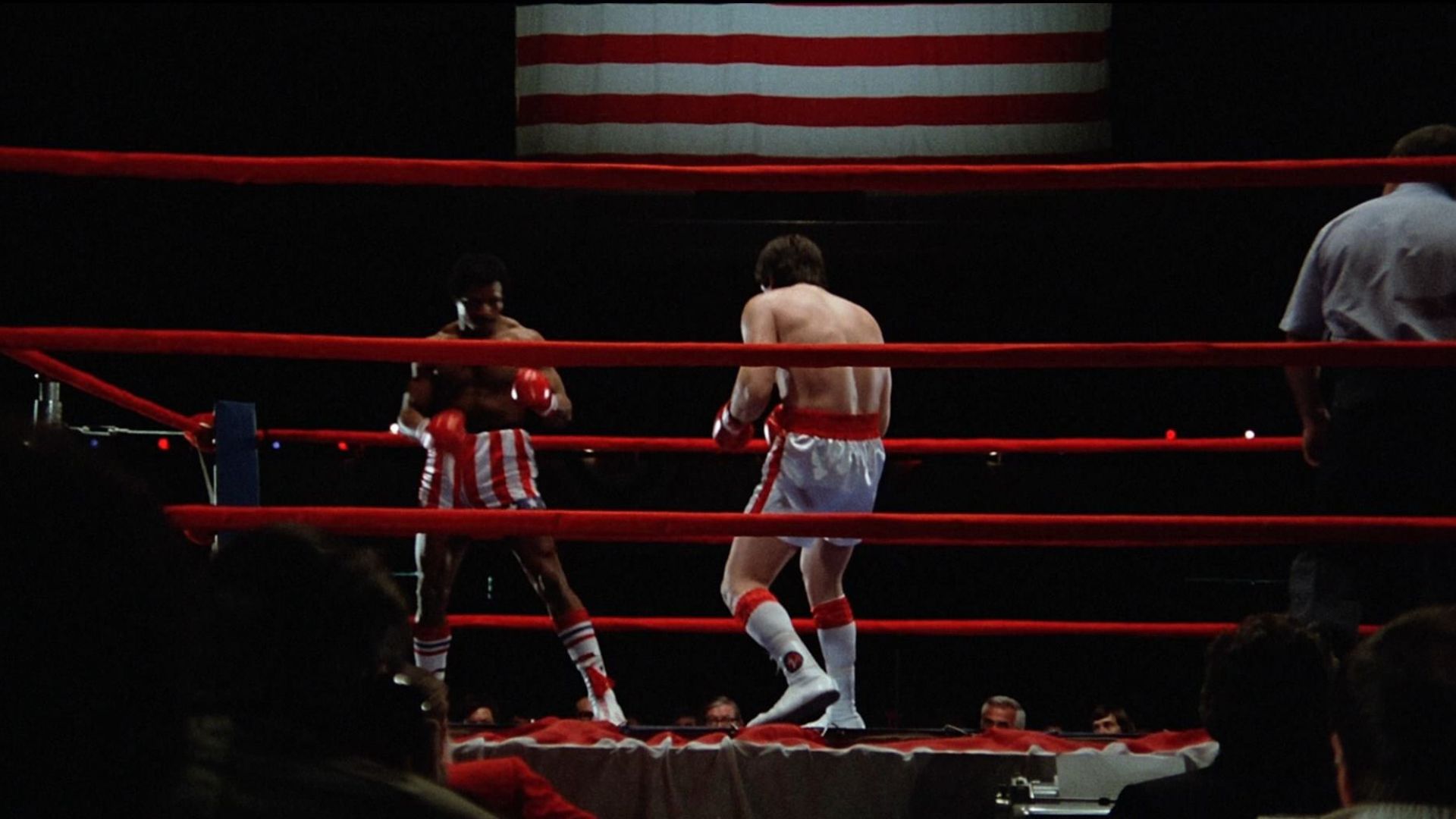

The fight scenes, when we got to them, had to be very carefully planned, because we had only one day of shooting with the large crowd, 11,000 people. That meant that it was expedient to really have our act together. A kind of storyboard had been prepared for the whole fight sequence and it served, as those things often do, as a good initial plan — although, when we actually got to shooting, we diverged from it quite often.

The way we shot the picture originally wound up with a semi-cop-out ending. Rocky loses the fight and the girl never does come to him. But after mulling that a bit, they realized that they really needed a kind of socko ending to fulfill the desires of all those people on Rocky’s side. So we went back to the Sports Arena and spent very little money on one extra day’s shooting with about 20 extras. On that day we shot the new ending in which the girl runs up into the ring and they embrace and so forth. One is always impressed by what editing can do — and, of course, there’s nothing new about that fact — but the film, in one of its earlier edited versions, left a lot to be desired, until the new ending was added and other things were pruned to make it come out as effectively as it did.

There are no studio sets in Rocky. The whole picture was shot on local locations, some of which were very small rooms with sagging floors that caused the flags and cutters to move when anyone walked across the floor. And, of course, we had the usual problems of taping lights up and attaching things to walls. One of the more interesting experiences was shooting in the Main Street Gymnasium downtown, which is one of Los Angeles’ old established fighters’ gyms.

Originally there was going to be a lot of 16mm footage in the picture which the old coach, played by Burgess Meredith, would show like training films for our hero. So we shot a lot of stuff in 16mm, but I think most of that was chopped out of the final cut.

For the fight sequences we used three cameras almost constantly. We found out that, more often than not, low cross-angles with the lights in the background were the most exciting. They were also necessary because, in actual fact, the arena was quite empty most of the time — but it also meant that we had to shoot with backlight and flares in the lens and that sort of thing.

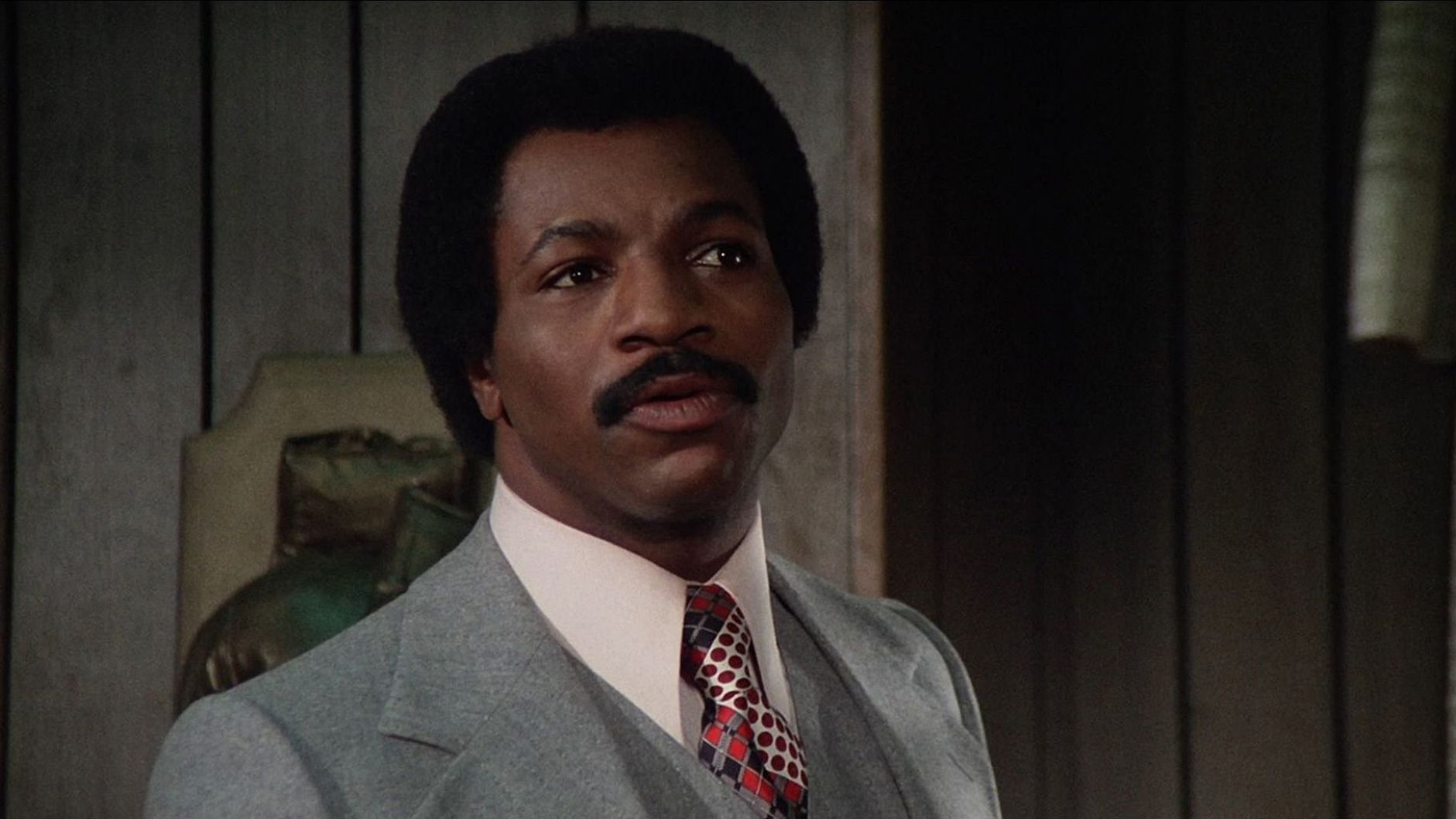

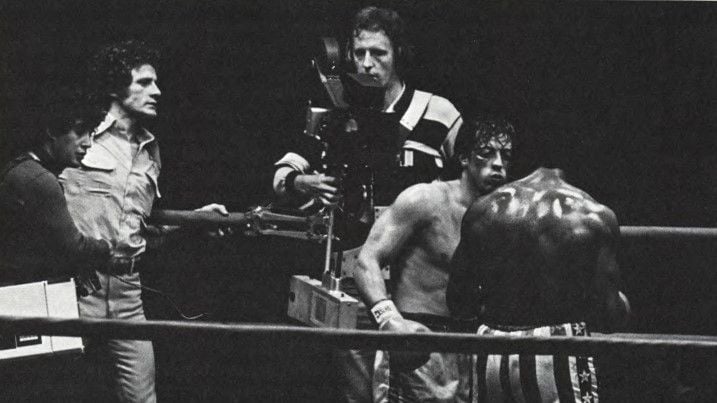

The two fighters, Sylvester and the actor who played Apollo Creed (Carl Weathers), were really terrific. Obviously the picture would have added up to very little without their efforts. They had the fight all choreographed to the nth degree and could just repeat and repeat any segment of the action. They knew where Round 13 was and where Round 5 was and just where they would be in the action for each round. Also, they were both in great physical condition. I think that the bane of so many fight films is that the guys who are portraying the fighters are really unable to take that kind of punishment. I don’t mean getting hit — because they were actually pulling their punches — but the sheer physical grind of repeating such action over and over again effectively in front of the camera. These two actors made it just a matter of recording what they did. I don’t remember what our shooting ratio was, but, of course, we shot lots of film.

As far as lighting was concerned, our main problem was just one of getting into those small rooms and finding places to hang lights. We often had scenes where we had to back the camera right up to the walls in order to get coverage. We used conventional lighting units — miniature quartz lights and Babies and things like that. We tried to put 2x4 spreaders across most of the rooms and hang our key lights from them. Sometimes we’d use bounce light, but more often than not in his apartment, which was kind of sketchy and low-key, we would just hang lights. We used a lot of photo-floods with snoots, too.

Occasionally, in larger rooms like the dressing rooms of the arena, we would bounce light off the walls, but basically I think the techniques could be described more as traditional motion picture lighting practice — key-lighting the people so they would have modeling and shadow sides to their faces, rather than relying on soft-light techniques throughout. My gaffer, Ross Maehl, who also worked on Save The Tiger, made it a lot easier. When you’ve got a gaffer who can understand what you’re trying to do and executes it without having to discuss every light, it helps a lot. In that respect, we were very fortunate that Ross could do the picture.

The interior locations were really difficult to handle because they were so small and cramped. Sometimes it almost seems as though people go out and try to choose the toughest locations they can find. The room in Rocky’s apartment where we did the most shooting was the smallest, and it probably could have been another room someplace else. We were shooting in a really crummy part of downtown Los Angeles and outside the windows of the apartment was the wrong view, so we ended up building a phony brick wall outside a real building in order to not see what was there. Sometimes you wonder how they pick locations.

Besides Rocky’s apartment, we had the house where his girlfriend lived, which was also tiny. We also had quite a bit of shooting that involved photographing action on television screens, especially in the sequence where Rocky sees himself in the newsreel. These were all put on video tape and photographed off a regular TV set, using a 144-degree shutter. This is supposed to be the magic angle where you don’t get flop-over or flicker bar. As I said before, we pushed all the interiors one stop and worked at a level of 100 foot candles, shooting at f/4.5.

At the Sports Arena we supplemented our lighting with the high intensity follow spots which they already had installed there — incredibly huge things that they use for ice shows and such. It was a boon not to have to get involved in installing our own follow spots. In the fighting sequences we used quite a bit of the existing light that comes from the overhead units that are built into the ring, and we augmented with some photo-flood bulbs and Babies that we stuck into the drape of the ring. We used only incandescent light inside the arena and never went beyond pushing one stop. The only arcs we used were Brutes for booster light outdoors.

Since we had our huge crowd for only one day, we had to plan our shots pretty carefully in order to make them inter-cut. Some days we had as few as 50 people, but we had to produce the effect and create the impact of the Coliseum filled with thousands of people. That was probably one of our biggest problems.

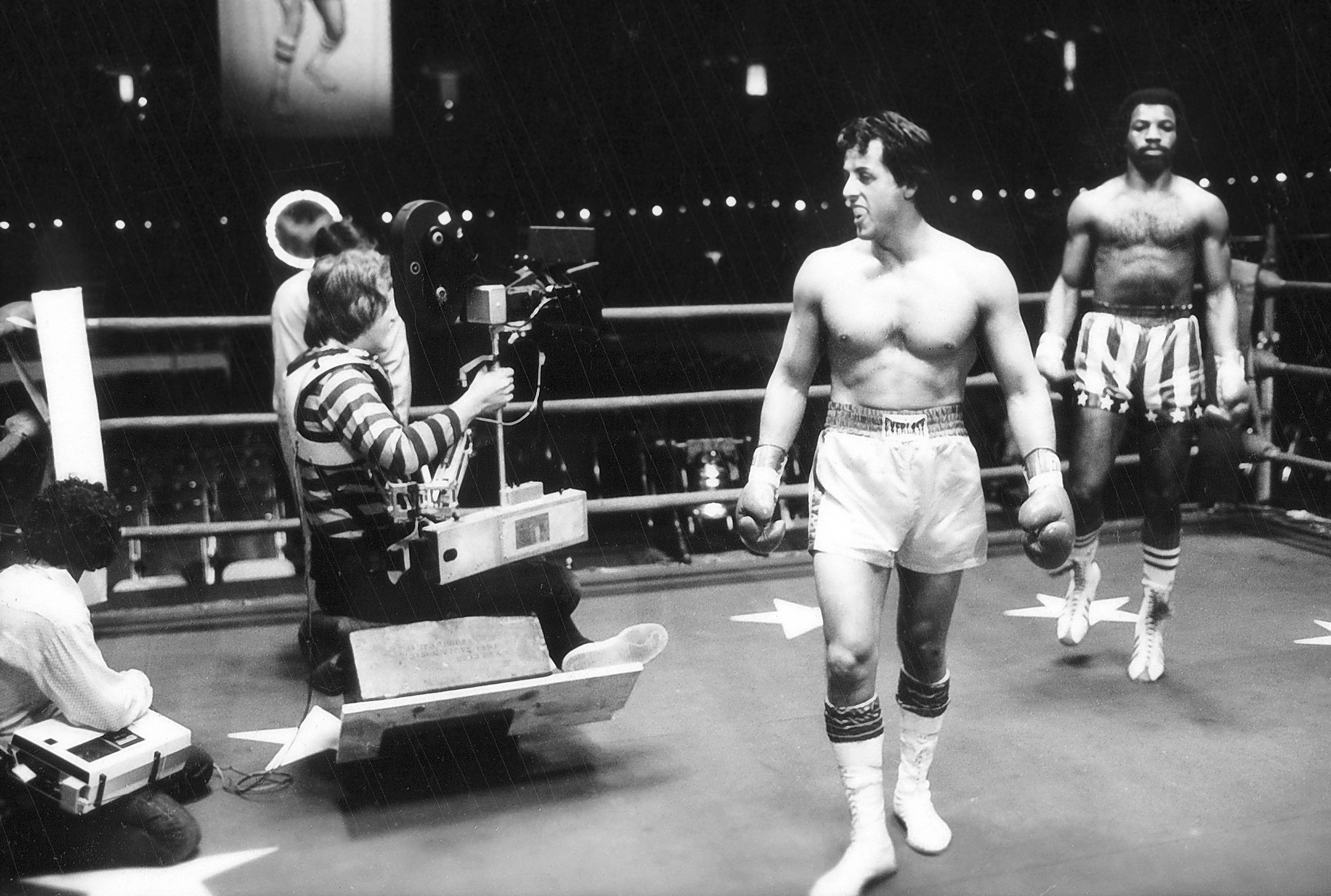

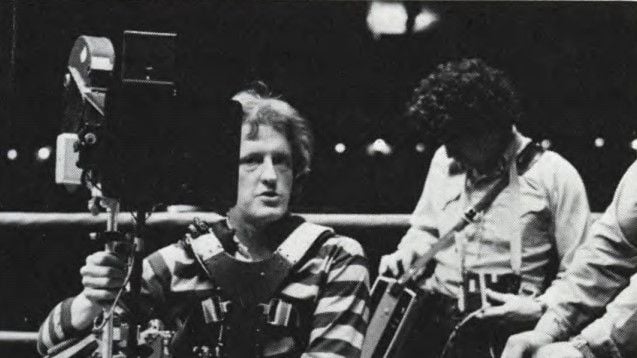

We used the Cinema Products XR35, which I like, as our production camera, plus some Arriflexes. We used the Arriflex 35BL for almost all the dialogue sequences in the ring where the fighters are talking to their seconds in the corner. There was not as much hand-held shooting as I thought there might be. Then Garrett Brown showed up with his Steadicam, which is quite spectacular, and what he shot represents the only really substantial handheld footage that appears in the picture.

The meat-packing sequence was shot at one of the big plants in east Los Angeles and there we used a little more bounce light, because the nature of the beast was overall illumination. That was one of the places where the Steadicam was used extensively and the lighting had to be a little less directional in order to avoid camera shadows. The plant interiors had a lot of fluorescent lights already installed, so there were occasions when we had to use blue light to balance and to avoid getting involved in a lot of filtering of the fluorescent sources. We used the fluorescents and blue lights and we bounced a few lights around and used some cross-lights and kickers.

One thing that we tried to do always was avoid that kind of one-source soft light effect. We tried to work in whatever kind of light seemed appropriate to the mood of the sequence. When working with John Avildsen previously on Save The Tiger, I did a lot of things with just bounce light, using white cards and nine-lights, but on Rocky we were striving for a little bit more of a key-light look and modeled effect.

Each time you do a film you try to embroider it with something a little new and just a bit different from what you’ve done before. So often, when I am prepping a picture in advance, I find myself thinking about a certain effect and searching for some way to get it — maybe even designing some special lighting units that might work — but when you come down to the nitty-gritty of it, you usually end up using conventional lighting units, with maybe an umbrella light standing by. I don’t mean to say that we are always emulating the older techniques, but there is something to be said for key-lighting and the use of harder lighting units. I think that the trend now is to find an average between the very soft-light “natural” look and what might have been termed the “Hollywood key” look. It’s just a little bit of everything. All of these various techniques are tools, and there’s nothing to dictate that one must always use one kind of lighting and not the other. I think that the main thing to say about Rocky is that we were always prepared to do anything. We could have gone into a place and just thrown up soft lights and bounced stuff around, but the nature of most of our interiors — which were, after all, moody night interiors — was such that we chose key lighting and used small quartz units and Babies to achieve those effects.

A lot of our most effective and exciting shots were done with long lenses, which tend to compress the action. There were a couple of the classic long lens shots, one in which he’s training with his dog and running toward us, for example. That one was done with an 800mm lens, as I recall. We also found that in the filming of the fight sequences, the long lenses enabled us to shoot with three cameras without photographing our own cameras, since we sometimes shot with cameras surrounding the ring on three sides. Even though the action was carefully planned and choreographed, a certain amount of accidental things do happen when people are in the fury of the fray. We kept our cameras pretty far apart, but we shot on three sides at the same time, because you never knew if a blow was going to connect or not on the screen. By having different angles, we were able to get proper connection of the fist with the jaw, and shots that looked right without having to plan all of them. In the one-camera situation, you have to have your camera in exactly the right place to get a proper angle, but this kind of action is so fast and furious that even though the actors did repeat their action remarkably well, there was no such thing as being able to put marks on the floor and have them hit exact positions.

We used zoom lenses on all of our cameras and I don’t believe we ever took them off. Nowadays that’s more or less standard technique, since the quality of zoom lenses is evidently approaching that of hard lenses. I’m aware that statement is debatable and probably refutable in terms of sheer mathematics, but what actually worked out in practice was that it was very expedient to use 10-to-1 zoom lenses on our cameras, so that during the course of a scene we could easily change focal lengths. For example, if Camera A were covering the main pattern of the action, Camera B could zap in for a closeup, much as a documentary unit might shoot.

The two actors who did the fighting put in a lot of time rehearsing every Saturday and Sunday morning at a gym in Santa Monica. John Avildsen had a little video camera and we went there one morning and photographed some of the action from angles that we might consider using. We could play the tape back right then and there and get some ideas as to what would work effectively. That was an interesting approach and it paid off somewhat. John also used his Super 8 camera as a notebook and shot a lot of stuff with it during rehearsals to get ideas about how later to photograph the fight.

In Rocky we kept the camera moving quite a bit, mostly through the use of the miniature Stindt dolly, which can move in very close quarters. However, John is a very naturalistic type of director who tries not to get involved with a lot of fussy effects that would stand out like a sore thumb. He works a lot with combinations of pans and zooms to try to use the zoom lens without making the audience aware that the lens is zooming, which, of course, is everybody’s objective. In Save The Tiger we had some very lengthy camera moves, where we would dolly in and around the factory and do some very long takes in one shot, but Rocky was a little more conventional, in that sense. We would stop and go and the scenes often did not dictate lengthy moves. We would simply move the camera whenever it seemed appropriate, while attempting to keep the dolly moves as unobtrusive as possible.

Of course, when it comes to camera movement, the film will be remembered mainly for the Steadicam shots, which were quite spectacular. Garrett Brown, who invented the device, is a very tall, kind of lanky, gazelle-like guy who was able to achieve some extraordinary effects. I’m sure there are other operators who can use the equipment effectively, but in this film Garrett runs up and down the steps of the library with Rocky and does a 360-degree move and it’s really incredible watching him use his equipment. I was most impressed, and I’m very grateful that Garrett made the picture look as good as he did with the contributions that he made. They were very important ones.

Crabe was later invited to become a member of the ASC, and also shot such features as Thank God It's Friday, The China Syndrome, The Karate Kid and The Karate Kid Part II.

Steadicam inventor Garrett Brown would later invited to join the ASC as an associate member, and has made invaluable contributions to films including The Shining (1980), which he discusses here.

Stallone would revisit his characters in numerous sequels, as well as the spin-off film Creed (2015).