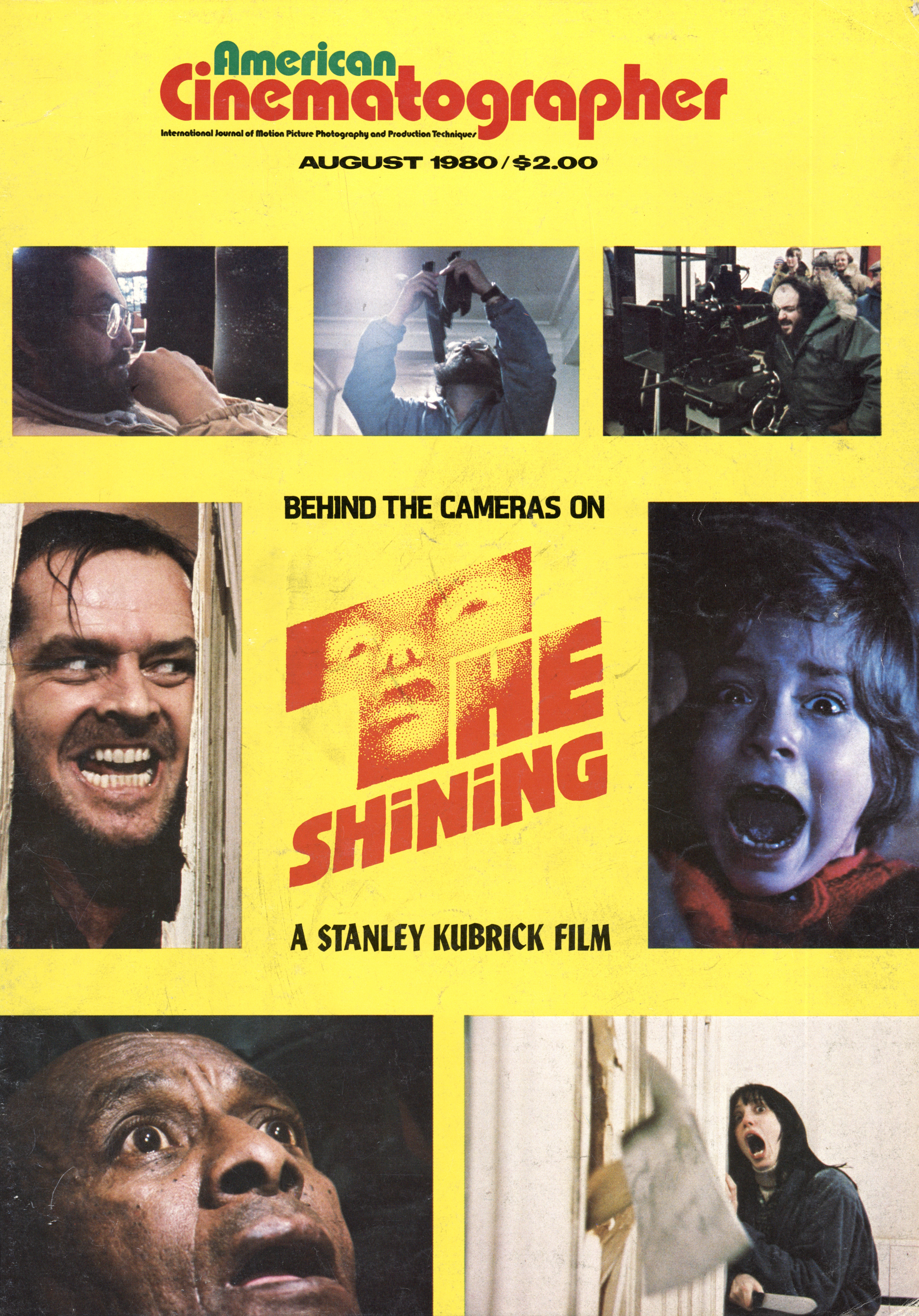

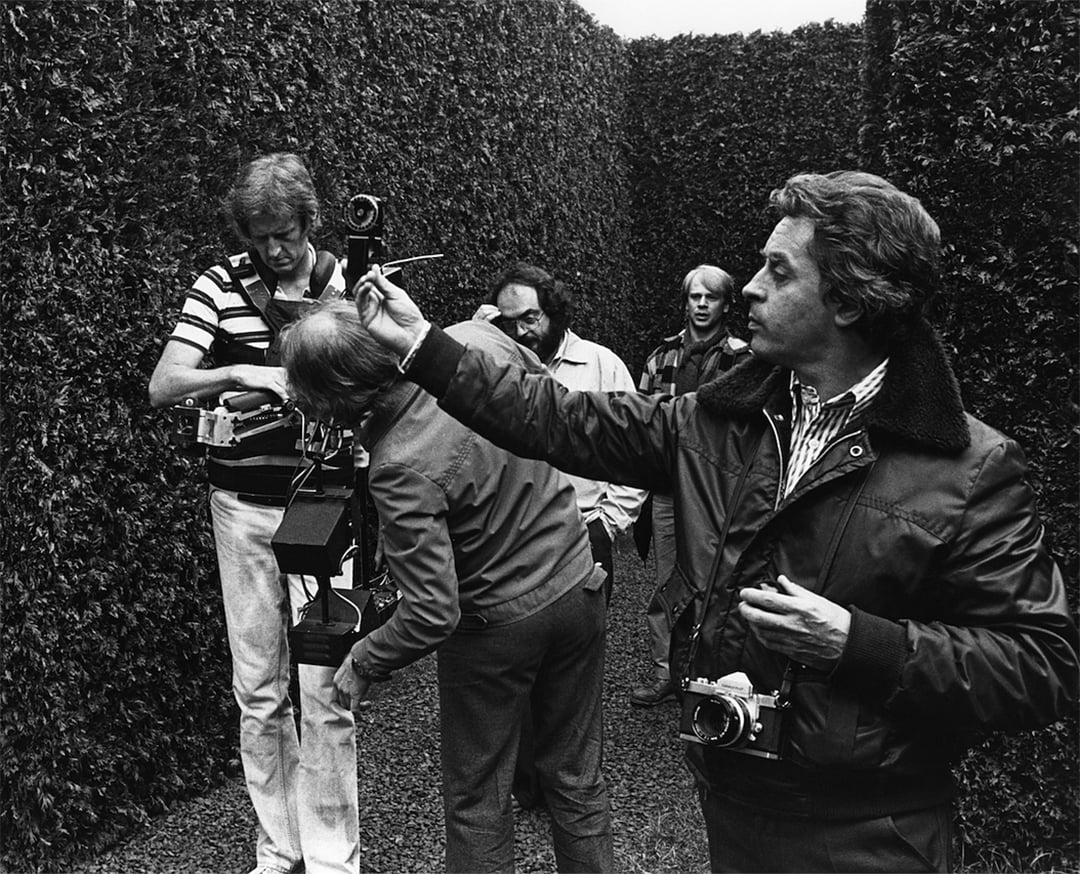

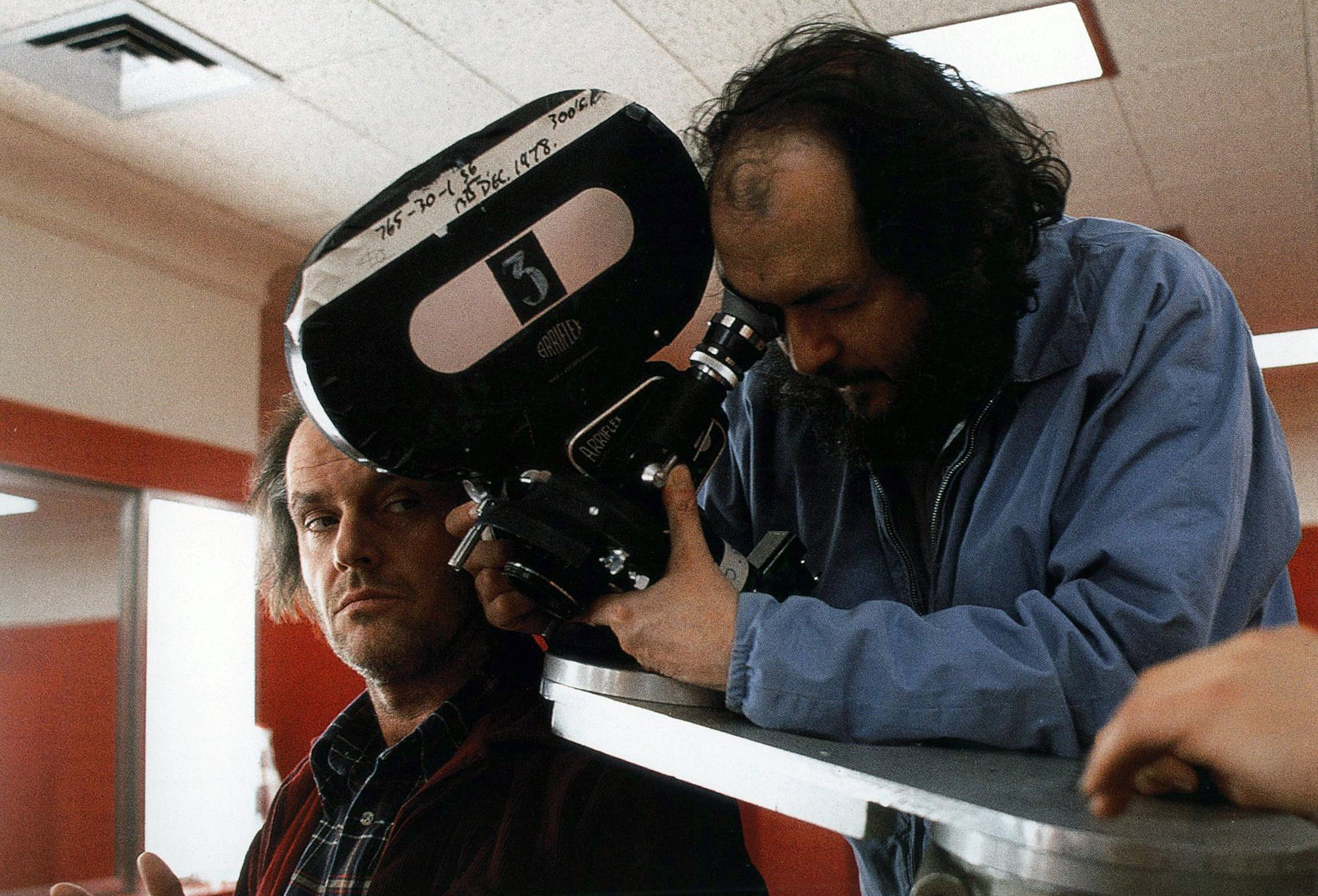

Photographing Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining

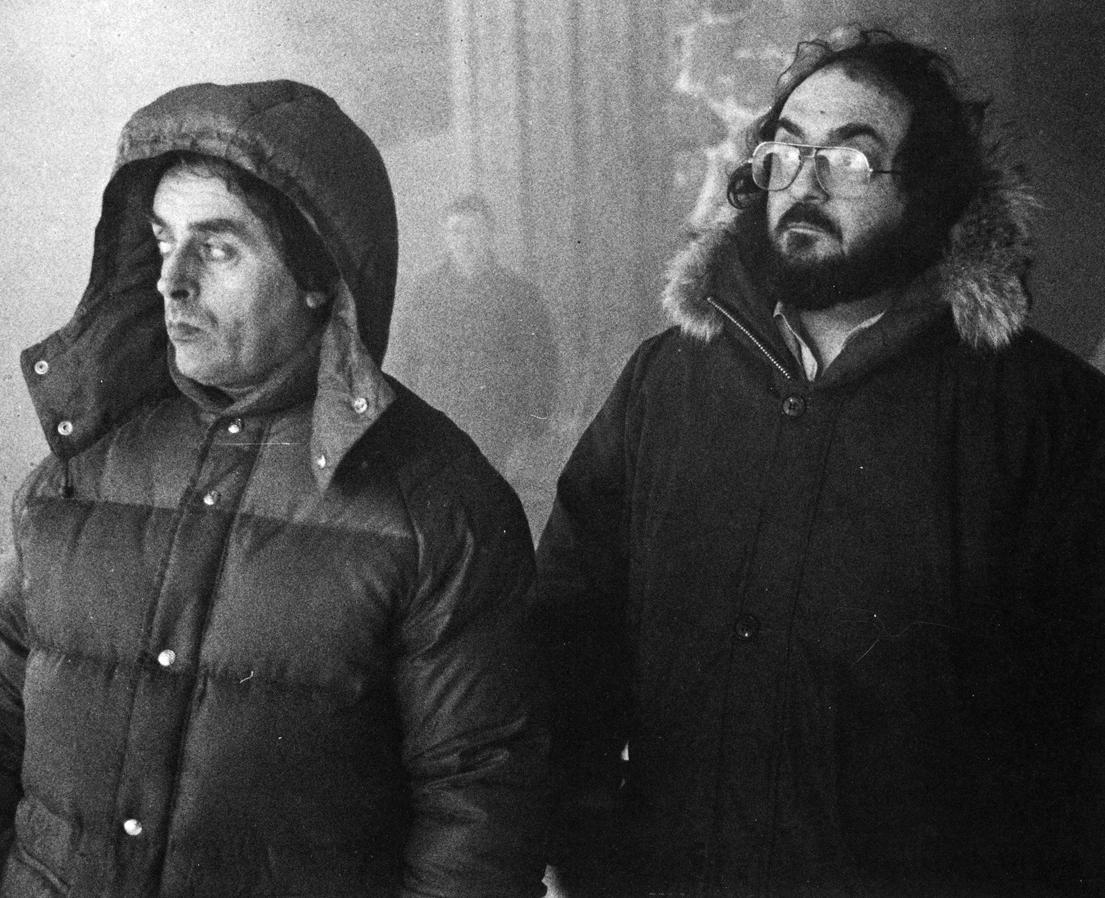

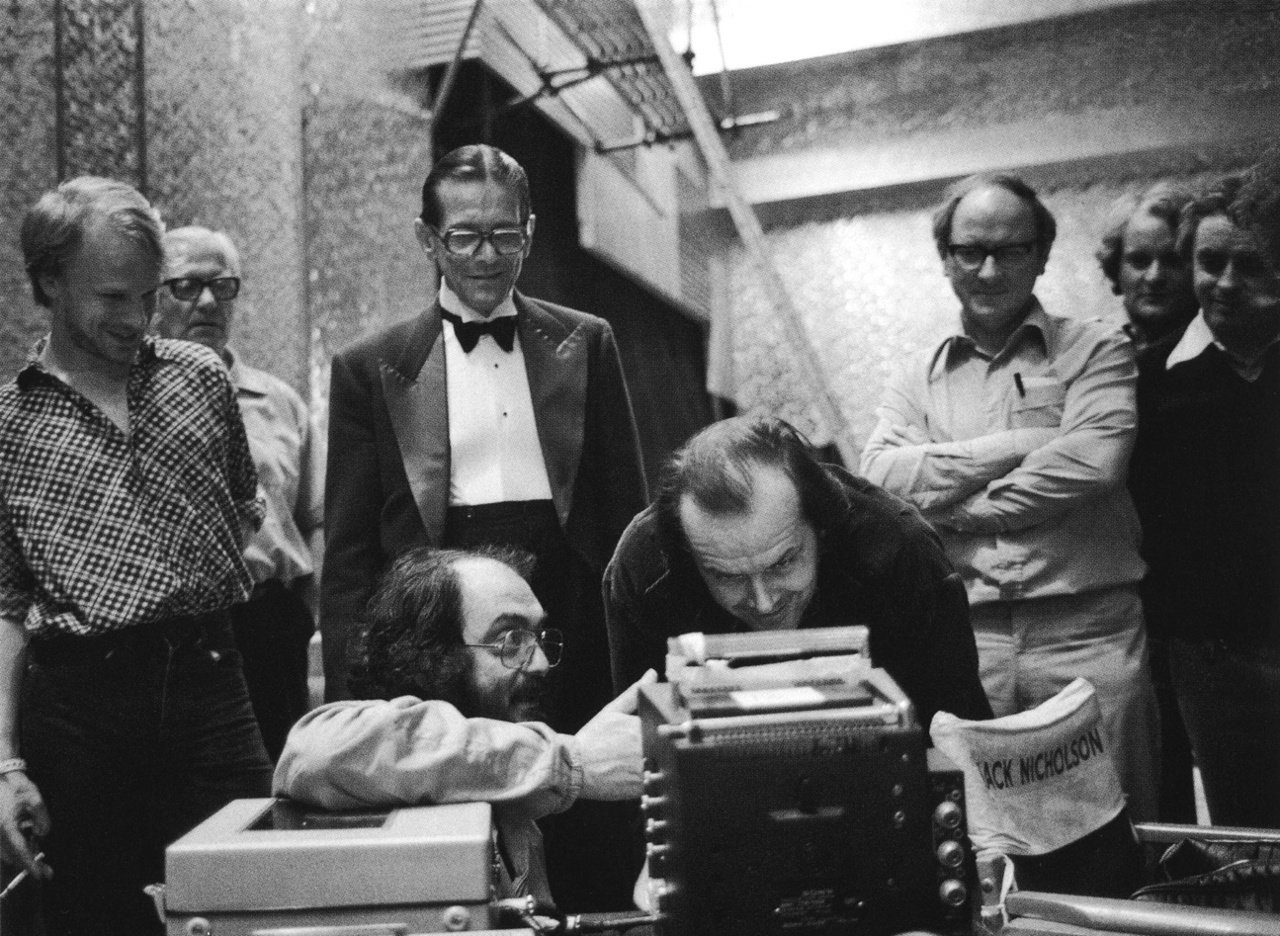

John Alcott, BSC details his collaborations with Stanley Kubrick and Steadicam creator/operator Garrett Brown while making the classic 1980 horror yarn.

The Shining, a Stanley Kubrick Film and Warner Bros, release, currently playing the screens of the world, is based on the best-selling novel by Stephen King. It was produced and directed by Stanley Kubrick from a script written by himself and Diane Johnson.

The Shining was photographed by John Alcott, BSC, who says that Kubrick “gave him his first break” on 2001: A Space Odyssey by asking him to carry on as cinematographer when the picture’s director of photography, the late Geoffrey Unsworth, BSC, had to leave the production after six months in order to fulfill another commitment. The two men have since worked together on A Clockwork Orange and Barry Lyndon, for which Alcott received the 1976 Best Cinematography Academy Award.

In the following interview, conducted by American Cinematographer editor Herb Lightman in New York, where Alcott was at work as director of photography on Fort Apache the Bronx, the cinematographer discusses in detail the challenges and techniques involved in photographing The Shining.

American Cinematographer: Starting from the beginning, can you tell me how much pre-production planning time you had for your assignment as director of photography on The Shining?

John Alcott, BSC: Stanley gave me the book to read about 10 months before we were to start shooting and, although I had several other shooting assignments in between, this gave me time to be constantly in touch with him and check on the situation regarding the set that was going to be built — whether it should contain 10 windows or only 5 windows, whether the fireplace should be located in one part of the room or the staircase in another — which proved to be a great asset for me in developing a visual concept for the film. This kind of direct contact prevailed throughout pre-production and I would always make a point of visiting him whenever I was back in England in order to see how the set construction was progressing.

Did you have a chance to study sketches or renderings of the sets before construction began?

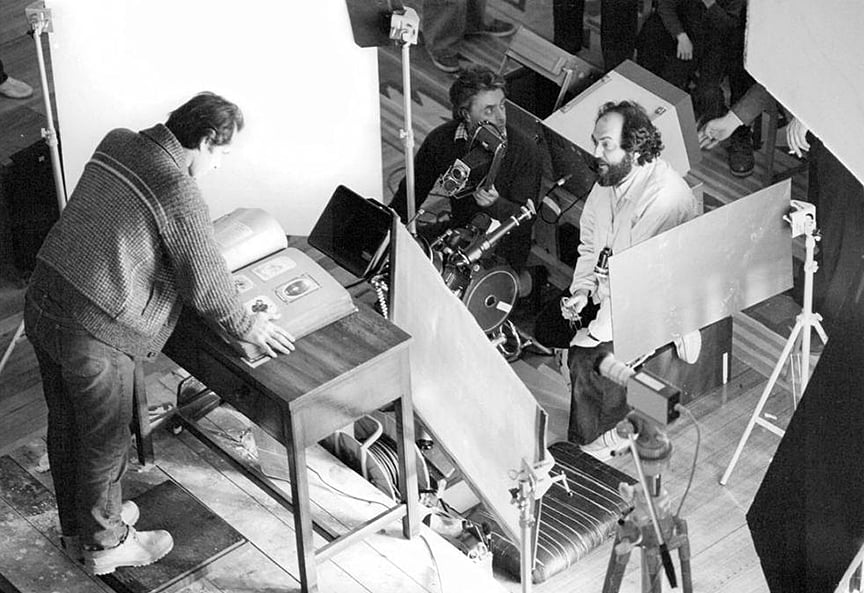

What we did at the very beginning was to have all of the sets built in the form of cardboard models. They were painted in the same colors and had the same scenic decor as we intended to use in the film and I could actually light them. With this concept of using artfoam cardboard models I could light the set with ten windows and then with five windows and photograph it with my Nikon still camera, using the same angle we would use with our motion picture camera. That would give us some basic idea of how it was going to look on the screen. We went all the way through the film like that, even for the sets which were built perhaps two months after we started shooting. All of the major sets — the hotel lobby, the lounge, Jack’s apartment, the ballroom and the maze were built in model form first, so I was able to do some careful planning. By this time we were probably about four months from our starting date and I would make it a point to visit the sets at least once a week, even though I had other commitments. Meanwhile, my two gaffers, Lou Bogue and Larry Smith, were doing the enormous amount of wiring necessary for the sets. [Editor’s Note: Smith would later photograph Kubrick’s final film, Eyes Wide Shut.]

Do I understand correctly that most of the lights used for the photography were actual practicals in the sets?

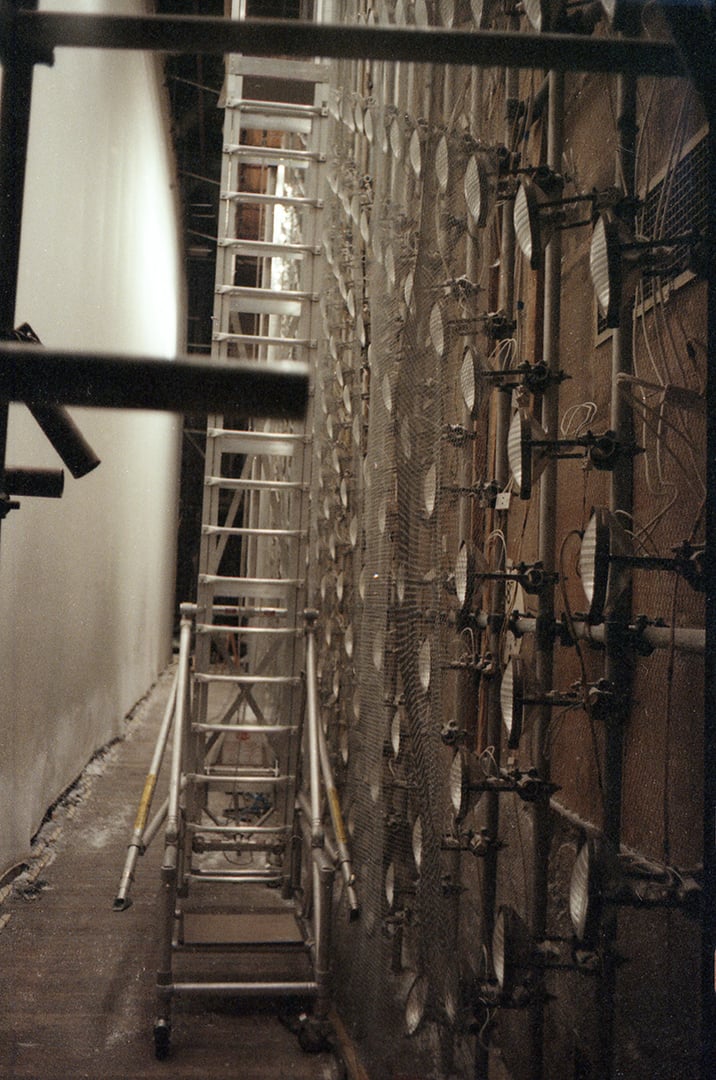

Yes, the lights were wired as actual practicals. They were part of the hotel. The gaffers started their work about four months prior to shooting because there was an awful lot of internal wiring to be done, and I would check at least once a week to make sure everything was going fine. They had to wire a great many wall brackets and chandeliers. For example, in the main lounge and the ballroom there were 25-light chandeliers which contained FEP 1000-watt, 240-volt lamps (the same lamps that are used in the Lowel-Lights). Each five of the lamps were connected to a 5 Kilowatt dimmer, so that I could adjust every chandelier to any setting I wished, and this was all done from a central control board outside the stage. The service corridors, which were outside the hotel lobby and the main lounge, were all lit with fluorescent tubes.

Fluorescent lighting always presents its own special set of problems. How did you cope with those?

Because the humming of the fluorescent tubes does indeed create a problem, all of the controls and ballasts and transformers were taken outside into the corridors of the studio, so there was no sound problem whatsoever. But this called for another great wiring job, because every tube had to have two wires going up and two wires coming back again. However, at least we eliminated the humming. We had no color temperature problem because the fluorescent tubes we were using were the Warm White Deluxe Thorne tubes, the ones which I’ve found in all my tests that come closest to matching incandescent lighting at 3200°K. In America, I use the General Electric equivalent of these tubes.

You mentioned that the dimming of the practicals was controlled from a central board outside the stage. Can you tell me how this worked out during actual shooting?

There were all on dimmers on the board and I could control the whole situation by remote control through the use of walkie-talkie. This was especially convenient for the Steadicam shots — and there were an awful lot of them. I could change the light settings of the chandeliers as the Steadicam was traveling about the set simply by talking to the control room. This happened in several instances and it was a great help.

The main lounge of the Overlook Hotel, which was built inside a huge sound stage at EMI Studios in England, nevertheless had very large windows which seemed to face the outdoors and let in a great deal of diffused “exterior” light. Can you tell me how you achieved that lighting effect?

Creating that exterior lighting was quite a project. We had the Rosco people make up an 80- by 30-foot backing of one of the Rosco materials which had the diffusing quality of tracing paper. They welded together the sections of material to give us this complete one-piece backing. The set for the lounge had a kind of small terrace outside with trees behind it. Then came the backing, and behind the backing there were mounted 860 1000-watt, 110-volt Medium Flood PAR 64 lamps. That was a lot of lamps and a lot of thing — and a lot of heat! I mean, you just couldn’t walk from one end to the other between the lights and the backing. You just couldn’t make it.

How were the lights mounted?

They were mounted on 40-foot tubular scaffolding and they were all built upright and placed at two-foot intervals. Each lamp was on a pivoted ball-bearing mount and they were all linked together, so that I could vary the light from a control inside. For example, we could start the shot off with the Steadicam pointing in one direction. I could have the light pointing toward me and then, by the time the Steadicam had traveled through the service corridor and around the back of the set and come in again, I could have the lights coming back again. This was possible because all the poles were linked together with one rod. You just turned the handle and the whole bank turned together. I remember going to a meeting and saying to Stanley, “The ideal thing for me would be if the lamps were on ball-bearings.” And he said, “Put them on ball-bearings. If it’s going to work, do it.” It gave us a terrific advantage, because I could very easily alter the direction of not just the whole bank of lights, but different poles and different parts of the backing, which, again, could turn in one piece. It was a great asset.

Assuming that all of this was worked out well in advance of actual production, how did things change as you approached your shooting date?

What happened was that when we eventually got the sets built — and some of them were as much as eight weeks in building — I started pre-production full time. This was three to four weeks before we started shooting, which enabled me to basically light all the sets before the cameras rolled. What I did was something that I had never done before: I lit all the sets and shot all my tests with a Nikon [35mm film] camera. I found that I could get around much easier and quicker and I could shoot 36 tests on one roll of film. Whereas, if I’d had a crew and motion picture camera wandering around on sets, it would have taken a lot more time. I did this purely as a lighting test and I could shoot varied tests with the different lighting effects, different settings, less chandeliers, more chandeliers, some on, some off, and so on. I did this continuously with all the sets and I used to view the results the next day. If I didn’t like something I could go back and decide on something else. By the time we actually started shooting the picture, virtually all of the sets were basically lit, so there was no kind of lighting that had to be done that hadn’t been done beforehand. As I say, I had never worked this way before, but I found it a great help and it left me with much more time than I’d ever had before.

Didn’t having almost all of the sets built in advance also add up to a great advantage for you?

Yes, I was very lucky in that respect. On most pictures all of the sets are not built in advance. They are built, struck and built again. But during the entire filming the sets were up continuously. Therefore, it was simply a matter of going from one set to another.

With so many sets up at one time, how did you keep track of your lighting logistics?

When I was about to do all of my tests, I had the art department make me plans of every set on foolscap-type sheets that I could file with all of the lights in the different positions. I could mark them down at the settings I established, so that when I came back to each set I would just give the setting plan to the control room and get them to make their settings accordingly. Then I would go around and check my measurements, because sometimes they weren’t always true, but basically they were there and it just meant making a final adjustment here or there to get back to the same situation we had left about two weeks before. Working in that way, I found that I had to make a plan and I had one for probably every slate number I shot. I found it to be invaluable.

How did your lighting plan work with the Steadicam shots?

Because most of the lighting was done within the set itself, using the practicals, if the chandeliers and light brackets were behind us, I would turn them up to a higher light level than the ones that I was photographing within the view of the camera, then, by the time the Steadicam had come around, I’d have changed the setting, reversed the whole situation. This had to be down on the plan, as well, depending upon whether we were going to come back and intercut something or pick it up somewhere. For example, we had problems with shooting all of young Danny’s scenes because he was only allowed to shoot 40 days out of the whole year. His time was from nine in the morning until four in the afternoon, and if his time ran out, we would suddenly have to abandon his shooting and go on to something else. We would come back to it maybe not even the next day. It might be the next week, because it would have been silly to come back and pick up just that one scene and then lose a day of this shooting time.

I noticed when I visited the ballroom set at EMI Studios that the walls were covered mainly with a gold metallic material and the lighting seemed to be almost entirely indirect. Could you tell me about that lighting?

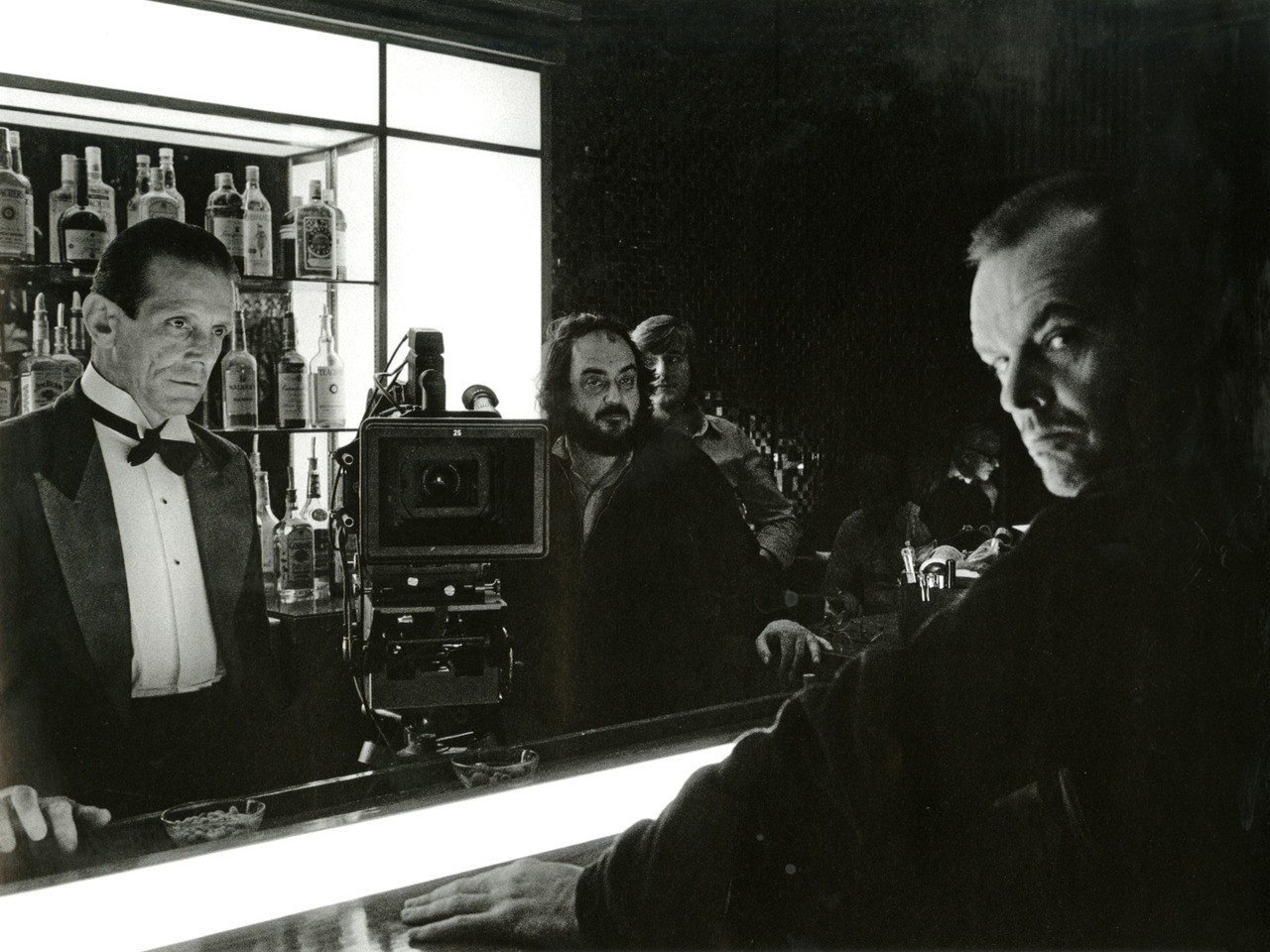

There were three troughs on either side of the ballroom and in each trough there were 150 100-watt domestic light bulbs. I had those on dimmers, as well, and, again, they were operated from the control room. They were on a 240-volt system, but most of the time I had them dimmed down to 60 or 7- volts, which threw a kind of golden glow and that’s the kind of light I used for the sequence when Jack comes into the ballroom and it’s all back in the 1921 period. The bar was translucent glass and the back of the bar was lit by 100-watt bulbs which were banked in boxes of 25 to each panel. The band was lit in a special way. For each person playing an instrument I used one Lowel-Light, just to pinpoint them out. In that set I had to rig the chandeliers up high because they reflected back so much from the mirrored surfaces of the walls that, at certain points, they looked unattractive. There were other times when they became very attractive, so I had to make up my mind that in certain scenes they would be on and in other scenes they would be off.

Most of the sets you have discussed have been the huge public rooms of the hotel. What about the smaller sets — Jack’s apartment, for example?

Jack’s apartment was lit, again, by fluorescent tubes, the same tubes I mentioned before. And inside all the practicals were wired, again, with the FEP 1000-watt, 240-volt lamps. So basically the rooms of this set, too, were lit by means of the actual practicals, supplemented sometimes with fill. I used to hang a little fill light behind the archway into the bedroom and the small lounge they had. But basically the illumination came from a top hanging light and the table lamps by the bed and dressing table were actually the practical lights themselves. Again, outside the windows we had a translucent backing with the 1000-watt lamps behind it, but it was a much smaller backing than the other one — only about 20 by 30 feet.

What about the lighting of the maze?

The maze was lit by the type of lights that are used for floodlighting in garden centers and that sort of thing. They were 1500-watt floods made by Thorne. That sequence was lit solely with those lights, with just a fill running behind. Garrett Brown did all the Steadicam work for us, including all that running around in the maze. I basically tried to place the lights so that everything was always in-picture that gave us a highlight, something which would expose the film properly.

Of course, we had the snow all over the maze, which was very bright and gave us a lot of luminosity. I was usually stopped down to T/5.6, and even sometimes T/8 in that maze — and that was normal development. The whole picture was normally developed, which is the first time I’ve shot a picture with normal development throughout. We wanted depth of field, so it might have seemed logical to force the development, but we had so much light coming through the windows from the backing that I could work at a T/2.8 to T/4 aperture most of the time and that gave us sufficient depth. We weren’t quite sure at the time whether it would be a good idea to force the development because of the new stock, but we had made one or two tests and the forcing had added more contrast. So we went ahead with normal development and it worked out just fine.

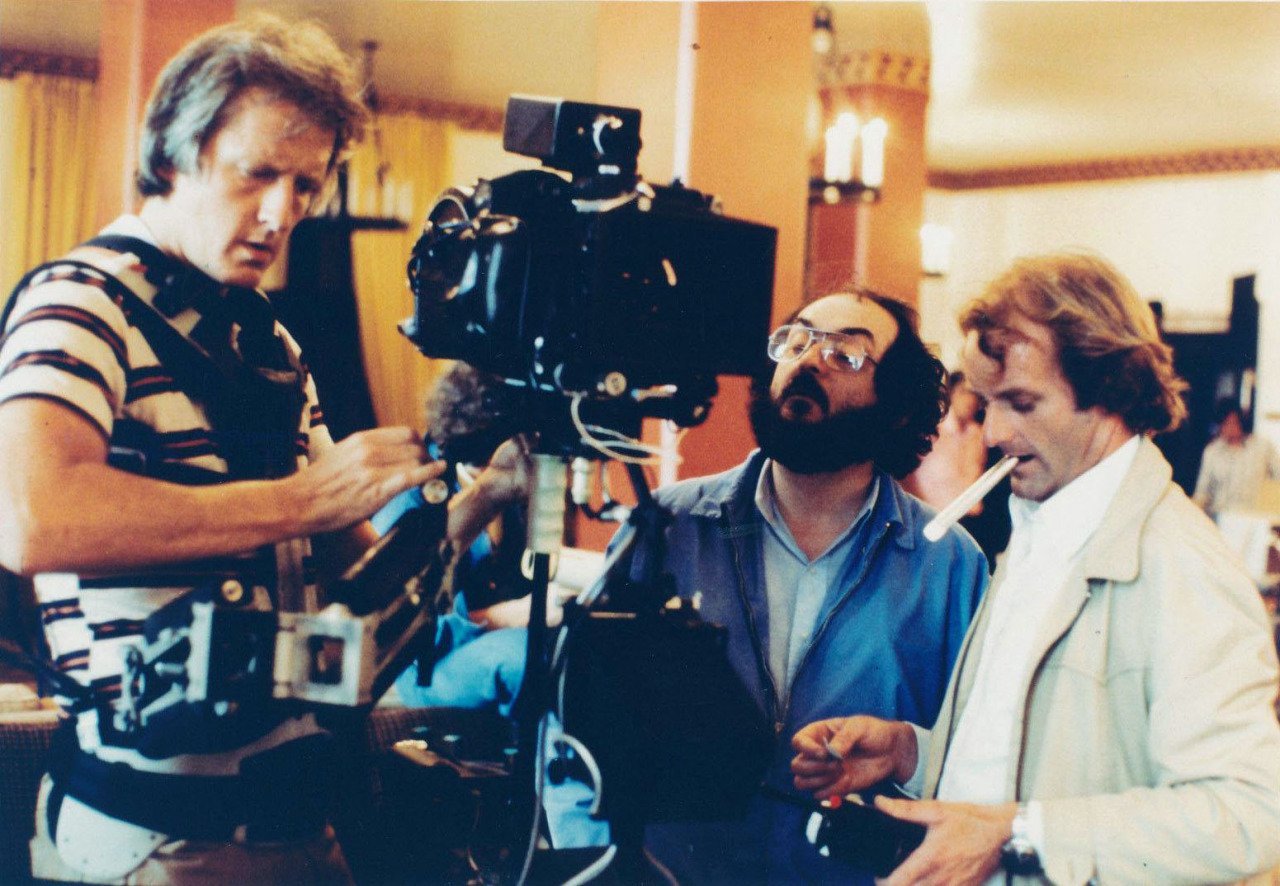

Can you comment a bit on the use of the Steadicam?

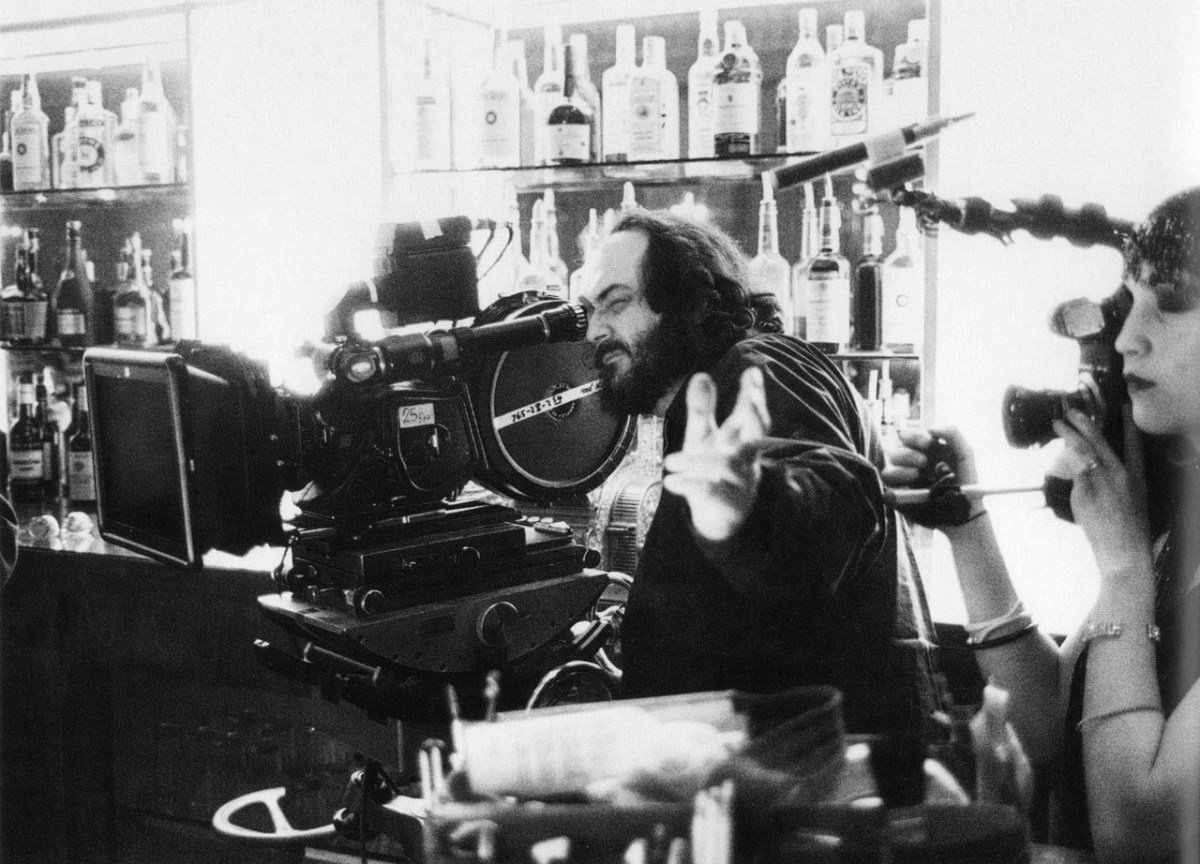

As I’ve said, Garrett Brown did all of the work with the Steadicam and it was used a great deal on this picture. It was used for most of the traveling shots you see when the Torrances are being shown around the hotel. For me, seeing the picture all cut together emphasized what a wonderful piece of equipment it is to use in that type of setting. Garrett is the ideal operator for it. Being such a tall man, he can go anywhere, and he seems to be so fit. It's quite incredible. He really is a perfectionist at the art of the Steadicam and I have a great admiration for his work. This particular film is a great showcase for the device because the story takes place in a very large hotel and one could only explain it being large and complex by traveling through it, and one could only travel through it the way we did by using the Steadicam. Otherwise, I don’t know how we would have done it.

I would say that the kitchen set alone presented a kind of obstacle course for the Steadicam. Isn’t that so?

Yes, the kitchen set was a maze in itself with all that equipment. When one travels through the kitchen in the first sequence there are twistings and turnings in and out amongst the ovens and the kitchen furniture — a kind of backtracking. I don’t think you could find a dolly that could do that. The Steadicam was an ideal piece of equipment in that instance. We used it often in shots where you would have to start off from a very difficult position and continue on to where you perhaps could use a dolly, but Garrett would end up on a composition as precise as anyone could have done it with a dolly and a Worrall head. I must say it was terrific.

How were the shots done of the boy running around in his little racing car?

That was the Steadicam, with Garrett operating it from a wheelchair. Stanley first had that wheelchair made up for use on A Clockwork Orange. It has the same basic construction as a wheelchair, but it was designed so that one could place different platforms on it, lie one it, stand up on it, sit on it and do all types of things while it was traveling around the hotel.

The exterior sets, including the rear facade of the hotel and the adjacent maze, were built on the backlot at EMI Studios. Can you tell me what kind of lighting was used for the night shots?

The lights in the parking lot on the outside of the hotel were ordinary streetlight-type fittings with 2000-watt quartz bulbs in them. They were far too bright for the camera, but the heat was too intense for any gelatine to take them down, so I had some perforated metal which I could use on the camera side of the lights. If there were a moving camera shot that showed two sides of the light, I would use the perforated metal sheet on two sides of the light. It acted actually as a neutral density barrier, because although the light flared out, it flared out around the metal sheet. In other words, the many holes were flaring into one another and becoming just one bright light-but not as bright as it would have been without the shield. The streetlights that did not show on-camera were left free of the perforated metal shields in order to provide maximum set illumination. They were used for all the exterior lighting except for the lights on the outside of the hotel. I wanted to light the hotel so that it looked weird and mysterious, but, at the same time, wasn’t lit by an unknown source. So I imagined that the hotel would have floodlights on it, as most hotels do, especially at skiing resorts — at the same time lighting it up, but not making it look too pretty. Then I also used smoke for the night exteriors, which again gave it a more mysterious look and softened the lights so that they weren’t so contrasty. The result was a kind of glow that was in keeping with the film itself, and especially the attitude of the hotel, as well. Although I used smoke, the intention was not to produce the effect of fog, but of cloud.

What kind of camera equipment did you use in photographing The Shining?

Again, on this picture, we used the Arriflex 35BL. We had one of them that was used solely for shooting as our main camera, and the other one was geared up for Garrett Brown to use on the Steadicam. He used that 35BL the whole time throughout the picture. The only time he used the Arriflex 2C was for the running shots in the maze. It was very difficult running in all that snow, which was actually a layer of salt and polystyrene about a foot deep. The Arri 2C made it much easier for him.

What kinds of filters did you use in shooting The Shining?

I didn't use any filters on this film, because it was supposed to look different. It was supposed to have a hard look to it and it needed a lot of contrast. There was supposed to be no attractive softness about it: The daylight was soft, of course, and the windows just naturally flared a bit, but without the use of the low contrast filters which I’d used on previous productions. In the sequence where Shelley finds out that Jack has been typing not a story, but the same phrase over and over, it was supposed to be early morning and I wanted to create a kind of mistiness to suggest the early morning effect. That was the only time I used smoke within the set, except for a very slight amount in the ballroom sequence, when Jack goes in and finds the whole crowd there.

Did you order corrected or one-light dailies on this film?

All the dailies were printed on one light, not so much because we didn’t want them graded, but because I’d already decided during our testing period what type of printing lights I wanted. Therefore, I thought it best to stick to the one-light system, because then, if something was a bit off, I could tell whether it was anything to do with me. Most times, in a situation where I am working on location, I like the laboratory to correct for me, because I’m usually working with mixed light or light from a source that is out of control altogether. In such a case, I like to see how the laboratory handles it. But in a studio situation like this it was much better for me to have control over the laboratory and know that the printing lights that had been chosen were continued all the way through. Then, if something wasn't right, I could alter it the next day-two points here or two points there.

What variations did you make in the color temperature of the light to enhance various moods of the film?

In the beginning of the film I used just the ordinary straight daylight system. I’m referring now to the 860 bulbs shining through the backing outside the windows. When the Torrances first arrived and checked into the hotel, the whole thing was lit that way, without any color filter whatsoever. Then, when it started to snow, I changed the whole lighting system to a full blue. I put a full blue on all the windows, and by that I mean that the gels were actually sandwiched in between two pieces of glass. So I had a double pane put on all the windows and that’s why it wasn't just a simple thing to make the change. It took the construction people at least a day to change all those windows in that large lounge (and also in the lobby) to a full blue, but it created a cold daylight effect for the snow sequences and gave me a much better contrast between the warm light of the chandeliers and the cold light coming through the windows.

The Shining is shot very straight. In other words, the visual treatment is devoid of all of the usual mysterioso effects that are conventionally used in horror films. That being the case, is there any instance in which you shot what might be termed a “special effect” in the camera?

There is a sequence looking down from the balcony with Jack at the typewriter and the fireplace in the shot. I wanted to get a full fire effect, a nice big glowing fire in the fireplace, but I didn’t want to reduce the general lighting in any way because I needed the depth of field. So I shot the scene all the way through without the fire burning, then rewound the film, killed every light on the set, lit the fire, opened the lens up to T/1.4 and shot the fire by itself — which gave me a nice glowing fire. It was something I thought would be different to do and it was worth a try anyway. But I think that’s really the only kind of "special effect” we did in the camera.

Did you use any type of video assist on the cameras while photographing The Shining?

Both Arri 35BLs were fitted with video cameras which enabled us to watch the scenes as played. This was especially valuable with the Steadicam, because everybody was virtually in the picture and the only way to view the scene was from outside in the corridor somewhere. Without the video set-up it would have been impossible to see what you had until you actually saw the rushes. I found also that the device which Garrett Brown has on the Steadicam for stop and focus control is great. I especially found the stop control to be extremely valuable in cases where it was an advantage to change the stop within the scene. I found that it was very good to be able to hold the control and be away from the camera, but watch the picture on the TV monitor. Most of the time it is very difficult to know what the camera is viewing when it is panning or tilting especially. You have some idea, of course, but with the TV monitor in front of you it’s easy to judge to the finest degree of stop control. I just hope that perhaps in the future all camera manufacturers will bear this in mind and incorporate it into their designs.

Did you use any HMI lighting on this production?

I think once, in Danny’s bedroom for a moonlight effect, but that was the only time. In fact, I haven’t used HMIs an awful lot until this picture that I am doing now [Fort Apache], but I must say that I find them very good. I think one has to be careful as to which make of lamp one chooses and which company one rents them from, because they have to be in tip-top condition. They’ve got to be maintained to their fullest. They’re not like an ordinary light that you can hire out and switch on and as long as it comes on it’s alright, because it isn’t with an HMI. There are contacts and various other things that must be absolutely perfect, because if they are not, that's when flicker can occur without being the fault of the frequency. In other words, it’s not always the frequency that gives the problem; it’s the connections and the bad maintenance of the lamps. But I always carry a frequency meter with me anyway, as a safeguarding factor. I think a frequency meter is one of the most valuable things one can have these days if you are going into HMIs, or even if you are going into fluorescent light for lighting, because in the northern part of England, for instance, you will often get a very weird type of voltage and you’ll never get rid of the flicker.

From what you’ve told me, most of your actual photographic light came from the practicals built into the set. Would you say that you used that kind of light more on this film than on your other films?

When it came to sticking with the actual lights that were built into the set, the chandeliers and other practicals, the answer is that I did use such lighting in this film more than in anything I’ve done before, but I had to do this for a very special reason — and that was the Steadicam. Because of the Steadicam, there was no way I could have used any floor lights. I couldn’t have any ceiling lights because the hotel lounges, if you noticed, are built in such a way that they are fixed; they are solid; they are there for keeps. The hotel was actually built wall-to-wall. As you went out of a hotel door you went into the studio corridor; it was that close. At any rate, in most instances, the lighting was what existed within the actual setting. I would use the chandeliers as my overhead lighting when they weren’t in the picture. In other words, I would use them as a supplementary light for the practicals which appeared within the scene. I’m speaking now of the wall brackets and the small chandeliers in the outer rooms of the main lounge.

But as “real” as practical lighting is, we both know that, from the aesthetic standpoint, it’s not always the best light with which to photograph a scene. That being the case, weren’t there times when, to insure the quality of the image, you had to use extra units to supplement the existing practical lighting?

In instances where I could use additional light — for instance, under the table when Jack is on the floor groveling after he’s had his nightmare — I did use additional lights. But these would be basically LoweI umbrellas with Lowel-Lights inside them, and I would supplement that with a full blue in order to get the same daylight effect. The fact is that under the table there was no light, no matter what I put through the chandeliers. Sometimes I would have to boost the daylight in instances where I needed the extra depth, as well. So the answer is that yes, I did use supplemental light in quite a few instances, when it was called for. By ‘‘called for” I mean if it was not possible to use the light existing within the set itself. But whenever possible I did use the existing fixtures for supplemental lighting. For example, if Shelley was talking to Jack in the mid part of the lounge, I would use a wall bracket with tracing paper to soften the light falling onto her and I would bring it up to give the required amount of exposurable light. All of our lights were on dimmers using increments from 1 to 10. If my general level were 4, I might bring the supplemental light up to 6 and then put on a quarter-orange or half-orange to keep the color temperature consistent.

You mentioned before that in the ballroom set the chandeliers tended to pick up as reflections in the metallic gold walls. Did the metallic materials cause any other problems that you can recall?

No, not really. In fact, it rather added to the whole effect. It reflected my light, which gave the set an overall golden quality. If I was fortunate enough, in the position the camera was in, to have the chandeliers on without any reflection, then I was fortunate enough to have the light of the chandelier bouncing off the mirrored surface, giving me an overall fill. The six troughs I mentioned-three on either side-gave me an overall top fill for basically the whole set. The practical small brackets around the ballroom I kept at a very low level because, being right next to the reflective material, they tended to burn out. I didn’t use them as a lighting source at all and they were much more effective as viewing practicals. On the dimmer scale oflto 10, the setting for those wall brackets was about 3. Each table had its own separate table light — an ordinary 25-watt bulb — but it was just enough, with the white tablecloth, to lend a luminosity to the features of the people seated around the table. That sequence had a period look to it — which, of course, it was meant to have.

You said that you used a bit of smoke in there. Was that all it took? You didn’t have to augment it with any fog filters?

No, just the smoke-and it was very, very light indeed. In fact, I tended to put it just in the background. You get to the point with smoke that no matter what you do in the foreground, it just never shows. So that’s why I used it on virtually just the background half of the set. The light from the troughs gave it an overall glow which softened it, as well. Then, of course, there was the hard light at the bar coming from the cabinets behind the bartender. The bar was sort of a set of its own within a large set, but the hardness of that light made the rest of it look much softer, more of an illusion. Had there been no bar there at all it would have been flat and uninteresting. It needed that contrast in the foreground to give it the depth that it had.

I gather from what you’ve told me that whenever you needed a cold look it was a matter of filtering tungsten with blue gels. Were there ever any times during the shooting when you lighted for daylight balance with arcs, using white carbons?

No, there was no time that arcs were used to create a daylight effect. The only time I used arcs was in the sequence where Shelley is running through the hotel just before she exits. She runs through the corridor into the lobby when she finds all the skeletons. I shot that with open arcs to get the very hard shadows which I found effective. And one other time, in the sequence where Scatman is phoning from his apartment in Florida, I used an open arc with a full blue filter to create a hard blue light, but that was intended more for a night effect. The only other light was the red practical burning in the background, which gave it a kind of separation.

The long establishing shots of what was supposed to be the Overlook Hotel actually were scenes of a real hostelry [the Timberline Lodge, Mt. Hood National Forest, Oregon]. Did you have the benefit of seeing those shots from the actual location before you had to light the hotel exteriors built on the EMI backlot?

Yes, plenty of time, and it was very helpful. I should like to comment on the wonderful sequence which Greg MacGillivray shot from the helicopter in the first sequence of the picture. It was a great introduction to the film and some of the most beautiful helicopter work I’ve ever seen.

In working with Stanley Kubrick on The Shining — which marked the fourth feature that you’ve done with him — did you adopt any different method or approach to working together, or was it basically the same working pattern that you’ve sort of established over the years?

I think that, as time goes on, Stanley becomes more thorough, more exacting in his demands. I think that one has to go away after having done a film with him, gather knowledge, come back and try to put that knowledge together with his knowledge into another film. He is, as I’ve said before, very demanding. He demands perfection, but he will give you all the help you need if he thinks that whatever you want to do will accomplish the desired result. He will give you full power to do it — but, at the same time, it must work. Stanley is a great inspiration. He does inspire you. He’s a director with a great visual eye.

Did you have much opportunity to discuss with him the visual style he wanted for this particular vehicle?

He said he wanted it to have a different approach from that of previous films. He stated that he wanted to use the Steadicam extensively and very freely without having any lighting equipment in the scenes. In other words, he suggested that we let the practical lighting work for us without using any actual studio lights. It wasn’t easy. In fact, at first it was quite worrying, because while I had visions of how it could work, I wasn’t sure it would actually come into practice. Even though you might prelight certain pieces of sets and lighting models, you can’t tell what is actually going to happen when you get artists in position. This you can never visualize until you are given a setup, which causes you to light it. By then the sets have been built and it’s too late to change much.

How would you sum up the working rapport that has developed between you and Stanley Kubrick, having worked together on four features in succession?

I feel that when you’re with Stanley the working relationship benefits from picture to picture. We’ve worked together since about 1965, and in working with him there is always a different outlook, a different idea: “Let’s try something different. Is there any way we can do it differently? Is there any way we can make it much better than it was before?" I feel that when you have as much time as I had on The Shining to make sure the sets are right and that the art director is building them to your lighting design, as well as his own design, it is a great privilege. You don’t have that privilege with someone who lacks the experience and the visual perception that Stanley has. He is willing to bend over backwards to give you something you may desire in the way of a new lighting technique and this is a great help. If you have somebody who is working that way it makes the job so much easier for you. I don’t think there is anything really different that has developed in our working relationship. He may be more demanding than he was before, but that makes it very easy for you when you go on to your next picture. To use an analogy in reference to our British game of Cricket: It's like practicing with five wickets and playing three. You defend five and then when you come to defend three, it’s much easier.

You’ll find an updated version of camera operator/Steadicam inventor Garrett Brown’s article from this same 1980 issue, detailing his contributions to the picture, here.

Douglas Milsome would later photograph Kubrick’s Full Metal Jacket (1987), among many other films, and become an active member of both the BSC and ASC.

The Shining was added to the Library of Congress National Film Registry in 2018, for future preservation. In 2018, the film was also selected as one of the ASC 100 Milestone Films in Cinematography of the 20th Century.

Further analysis of The Shining can be found in Collative Learning’s multi-part video series, starting here.

For access to more than 100 years of American Cinematographer reporting, subscribers can visit the AC Archive. Not a subscriber? Do it today.