The Sopranos: Mob Psychology

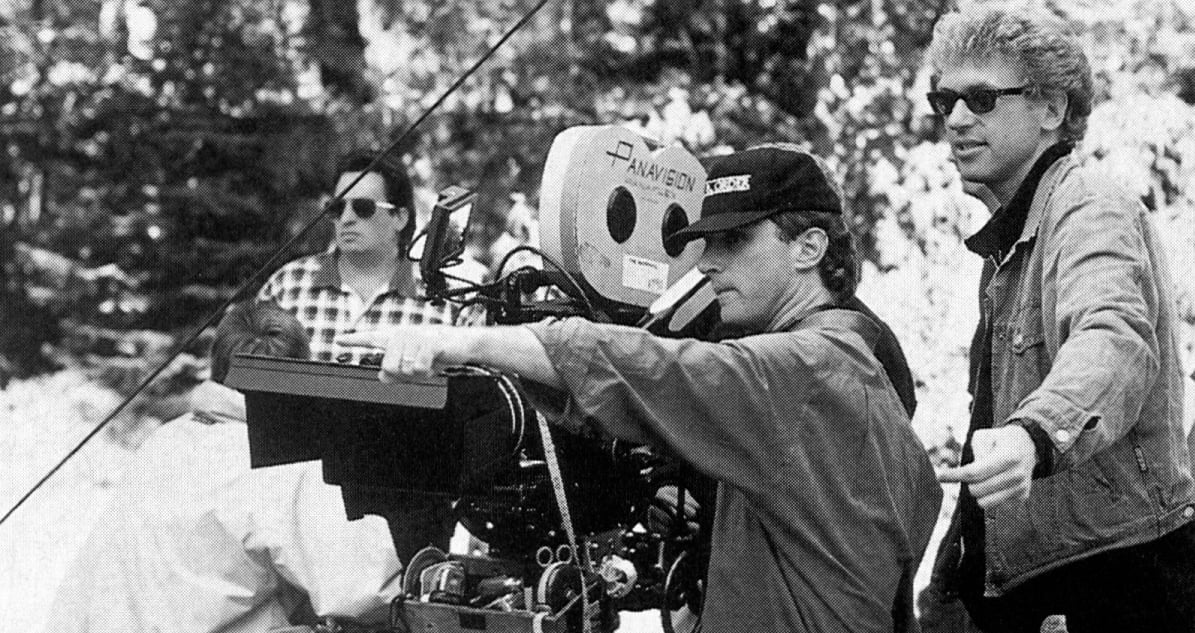

Cinematographer Phil Abraham aims for both drama and humor on HBO’s popular and critically acclaimed gangster series.

This article originally ran in AC, Oct. 1999

Unit photography by Anthony Neste, courtesy of HBO

The HBO series The Sopranos has caused a sensation like few other television shows in recent memory. Creator David Chase’s dark, realistic, yet subtly comic view of organized crime at the century’s end debuted in January of this year with a moderate amount of fanfare and expectations. By mid-season, however, the show had become a ratings smash. Even the most hardened critics were ecstatic in their praise. The venerable New York Times raved that The Sopranos may be the “greatest creation of American popular culture of the last quarter-century.”

The Sopranos swept this year’s Emmy announcements with 16 nominations, and is the first pay-cable series to be nominated as Best Dramatic Series. The second 13-episode season of The Sopranos will begin airing in January of 2000.

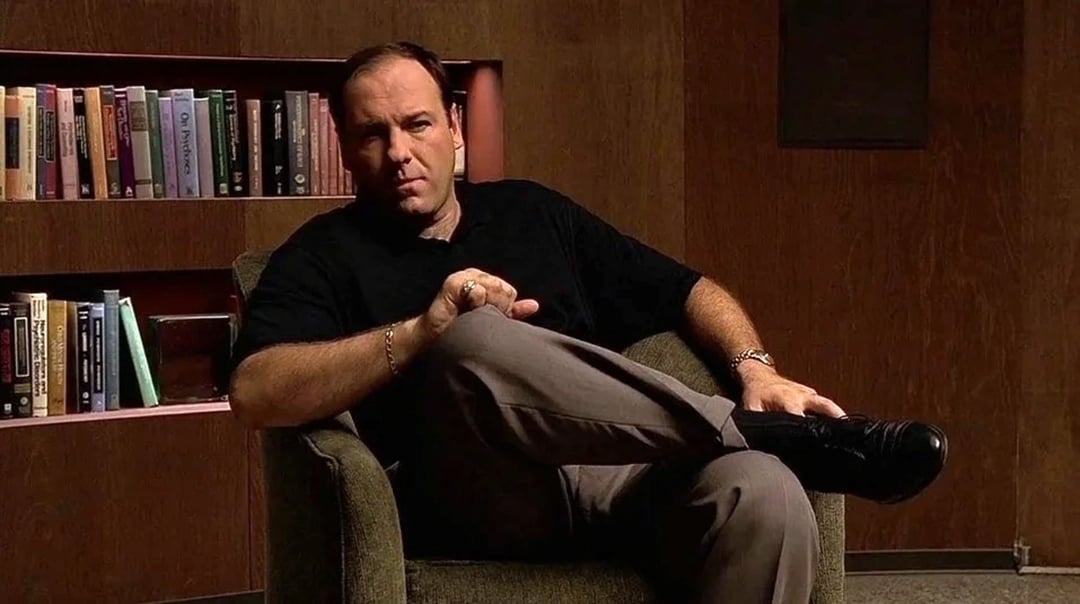

A family drama set in a modern mob milieu, The Sopranos centers on Tony Soprano (James Gandolfini), a hulking middle-aged husband and father who just happens to be a high-ranking mobster in northern New Jersey. Soprano desperately wants to be a nice guy when he’s off the clock, but this inner yearning conflicts with his professional life as a murderous earner. On the home front, Soprano is pressured from all sides by the members of his dysfunctional family, who include his angry and spiritually hungry wife, Carmella (Edie Falco); his accomplished but unpredictable teen daughter, Meadow (Jamie Lynn Sigler); and his beloved but tenacious Uncle Junior (Dominic Chianese), the crime family’s de facto boss, who, encouraged in no uncertain terms by Soprano’s scheming and vengeful mother, Livia (Nancy Marchand), tried to have Tony killed toward the end of the first season.

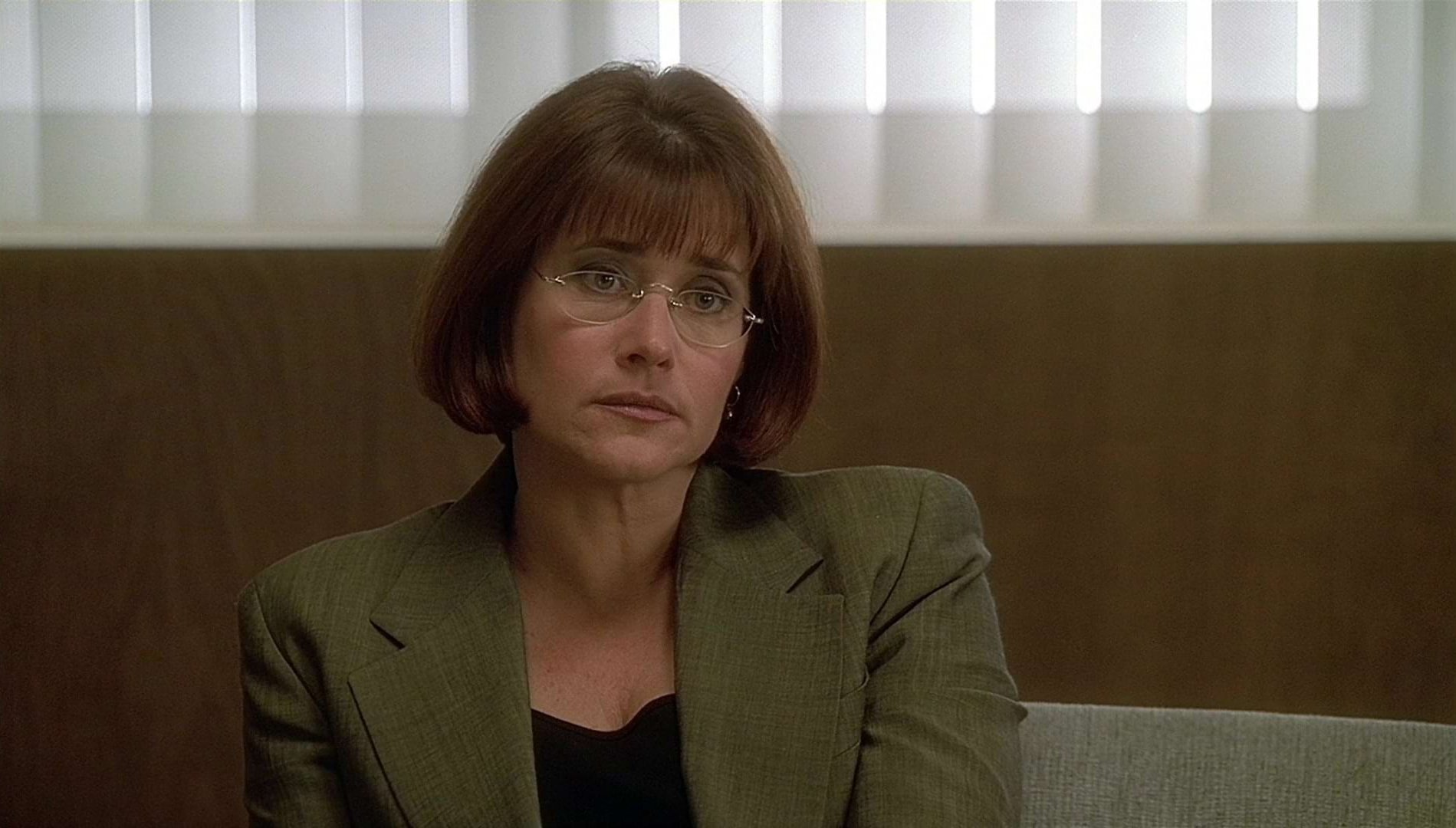

This constant emotional onslaught has caused Soprano to suffer repeated collapses with no apparent physical cause. In an attempt to regain his equilibrium, he has sought the counsel of an attractive Italian psychiatrist, Jennifer Melfi (Lorraine Bracco), who immediately prescribes Prozac. The doctor and her patient battle and flirt, and the closer she gets to helping him unearth the true cause of his problems, the more explosive their relationship becomes.

Liberated by the freedom of pay cable, The Sopranos melds a moody, realistic photographic style, audacious writing, insightful casting and bravura acting to tremendous effect. There isn’t a weak performer in the cast, which is led by Gandolfini (whom New York magazine’s John Leonard described as “a marvel of baffled machismo”) and Falco.

The actors who portray the Soprano crime crew are equally compelling. Michael Imperioli, who played the memorable role of Spider in Martin Scorsese’s mob masterpiece GoodFellas, strikes all the right notes as Christopher, Tony’s young but ambitious lieutenant. Longtime Bruce Springsteen collaborator and first-time actor Steven Van Zandt is perfectly cast as tough topless bar owner Silvio Dante, a flashy dresser who possesses a penchant for arson and murder. Colorful Mafia movie regular Tony Sirico also makes an impact in the small part of the loyal low-level soldier Paulie Walnuts.

The show’s tremendous success in its first season has resulted in a larger production budget that will allow about half of the next 13 episodes to be produced on a nine-day schedule instead of eight (The Sopranos normally shoots six to nine pages per day). The extra cash has also led to the addition of new family members, such as Tony Soprano’s formerly estranged sister, Janice (Aida Turturro), a New Age disciple. The increased budget will even allow the show’s creators to film one of this season’s episodes in Italy.

Chase (executive producer of I'll Fly Away and the final two seasons of Northern Exposure) acknowledges his fascination with the contemporary mob world. Since he feels that the milieu is influenced as much by GoodFellas and The Godfather films as it is by old Italian traditions, The Sopranos is packed with mob-movie and even cinematography references. In one episode, for example, a group of mobsters argue over the correct way to effect a “message” killing; some insist that the classic approach is a bullet in the eye, a la Vegas hotshot Moe Green, who is shot through his thick black glasses in The Godfather. Other enforcers disagree, maintaining that the message kill traditionally requires a shot in the mouth. Paulie Walnuts finally resolves the argument by agreeing that the mouth shot is correct, while noting that the bullet through Moe Green’s glasses in The Godfather “was just the way Francis framed it, for the [cinematic] shot value.”

In the show’s very first episode, there was even a direct dialogue reference to Gordon Willis, ASC, who photographed all three Godfather films. Although first season director of photography Alik Sakharov and creator Chase were also inspired by the work of other great cinematographers, such as Vittorio Storaro, ASC, AIC, they used Willis’s Godfather work as their main reference point. The result was a visual style that was both realistic and highly dramatic (see Points East, AC Oct. ’98).

“I decide how to light by looking through the eyepiece. Cinematographers talk about having elaborate lighting plans, but I’ve found that despite all of their pre-planning, they’re usually peering through the eyepiece and letting the look take shape as they’re lighting.”

For the coming season, the cinematographer’s duties have been assumed by Phil Abraham, who served as Sakharov’s camera operator, as well as director of photography on six of the first season’s shows. The cameraman, whose credits include the independent features Trouble on the Corner and Cherry, plans to refine the realistic, non-glamorous look that he helped Sakharov implement.

Sakharov himself says that he strove to use the type of lighting found in real life as his starting point, explaining, “The idea was to re-create or enhance the lighting one would find in life, so it would work onscreen both technically and dramatically.”

As an example of this approach, Sakharov cites a scene in which several mobsters gathered for a nighttime meeting in the back room of a pork store. “When the actors came through the back entrance, we had a single bare lightbulb hanging from the ceiling. As each actor passed in front of that light, we’d see a silhouette that would provide just enough information to tell the audience which character they were looking at. The actors would then walk into the actual back room, which was lit by ceiling fixtures; we therefore illuminated the set from an overhead box that was parallel to the floor. That approach gave the actors deep eye sockets, and we just went with it because it suggested the reality of the surroundings. We deliberately went for such familiar visual cues, to emphasize the sense of reality.”

One of the most unusual aspects of the show’s cinematography — which is consistent with Sakharov’s goal of realism, and also a key to making many of the days — is the permanent illumination in place around the kitchen and family room of the Sopranos’ suburban subdivision mansion. The kitchen set is ringed at ceiling level by long wooden troughs that hold bat-strips, simple 4' wooden strips fitted with 16 closely-spaced 100-watt frosted household bulbs. The bat-strips themselves are connected to a dimmer to allow the easy adjustment of fill levels. The idea behind this strategy was to facilitate quick setups and create realistic, household-style light that would echo Gordon Willis’s Godfather cinematography. Abraham notes, “We keep it warm, especially in the family setting; the household bulbs come in at 2800° or 2900° Kelvin. Although the look is warm, it’s not really deviant [when used in conjunction with 3200°K tungsten-balanced film].”

Lighting the many scenes that take place in the kitchen is therefore a matter of dimming and then modeling the bat-strips with flags, reflectors and teasers. Abraham additionally employs a handful of harder 3200°K back and rim sources, which are also dimmed frequently to warm their color. For this season’s work, three 2K Baby Juniors are also permanently hung around the ceiling’s perimeter. These units are set on a pipe and can therefore be moved easily to help separate the actors from the back¬ ground, no matter how a scene is blocked. “I’ve got GAM boxes on the Baby Juniors so I can vary the throw,” Abraham explains. “But even with the diffusion, they give a nice hard edge in contrast to the soft, shadow¬ less lighting from the bat-strips.”

For the sake of the highlights, the warm light from the bat-strips (which work together like one big soft source, thanks to the tight spacing of the household bulbs) has been slightly cooled down with gels since the middle of the first season. Abraham explains, “I have ¼ blue gels and opal diffusion built into the bat-strip troughs, because Alik found that when you’re working at too low a light level, the bulbs reach a certain curve where you can’t get a real white anymore.”

To help control spill, eggcrates were added to all of the batstrip troughs last year at mid-season, and Abraham has also installed six large Duvateen teasers on pulley rigs in the kitchen. He explains, “I can bring the teasers right down to the tops of the actors’ heads if I want. We also painted the walls slightly darker this year in order to keep the spill under better control.”

The master bedroom set also has permanent bat-strips. The Sopranos’ dining room, foyer and formal living room are permanently lit with Chinese lanterns fitted with tungsten-balanced Photofloods and shrouded with Duvateen skirts. The balanced floods are dimmed to warm up their output.

The show’s built-in broad, soft sources do not mean that the lighting is always even, however. “You can’t make things too dark with the strip lights in the Soprano kitchen, but it doesn’t always have to be bright kitchen light either,” says Abraham. “In the first show of the second season, there are some moody scenes set in the kitchen. There’s a bittersweet moment at the end of the first show, and I thought it might be nice to introduce a bit of the harder, moodier look. I used hard light coming in through the windows with a low fill level from the bat-strips.”

Another advantage of the batstrips and the Chinese lanterns is that the stage floor can be kept free of light stands. This allows for greater flexibility in blocking and camera movement, and also help the cinematographer with the protection needed for the show’s 1.78:1 HDTV framing. With some frustration, Abraham relates, “I was hoping to convince HBO to show The Sopranos in a letterboxed 1.78:1 format this year, and to compose solely for that format, rather than for both 1.33:1 and widescreen. Unfortunately, their viewer surveys consistently proved the public doesn’t understand that they’re getting more, not less, with letterboxing. As long as we’re going to the trouble of keeping lights out of the wider frame, which can be a bit of a hardship, I thought the audience should be able to see the whole image.”

Abraham also uses the batstrip lights on location as needed, though not as often as Sakharov did. “It’s not usually a matter of formal style,” he says. “On location, the use of the strip lights is dictated more by time and space restrictions. If I’m in a location with a low ceiling and I’m shooting two people against a wall, I can hang a bat-strip on the opposite wall coming back at them, with a shelf or teaser to keep light off the wall behind them. The strips are a handy light for that situation — as are Chinese lanterns, which I’d be just as likely to use. If I had more room and time, I might use more conventional lighting instruments.”

Abraham does note, however, that the strip lights and lanterns both have a characteristic that makes them ideally suited for the moodier approach he takes to the realistic Mafia-milieu locations, with their inherent air of menace. “Both the strips and the lanterns give us a glorious three-quarter wrap of light that falls to zero in the shadow area,” he says. “I think that falloff is inherent in a household-style bulb, as opposed to a tungsten filament in a movie lamp housing.”

Although these offbeat instruments can provide rich shadows, Abraham has slightly modified the show’s signature use of deep shadows on faces and backgrounds. “We still use very low amounts of fill for facial shadows, but most of the time I’m using just a touch more fill than Alik did. I’ll often put a silver beadboard at a three-quarter angle to skip a little reflection into the dark side. Of course, sometimes I’ll just let it go completely inky-dark.”

While he doesn’t generally go quite as dark as Sakharov, Abraham makes enthusiastic use of dark mood lighting whenever it’s appropriate. “For the second season’s first show, we did a long montage sequence with lyrical shots and deep shadows,” he reveals. “We have a wonderful shot of Tony Soprano coming into his house late at night and sneaking into the basement. We start on a still frame of the dining room looking up to the main staircase, and then Jim [Gandolfini] comes into frame in half silhouette and moves into a little front light. We follow him as he opens the basement door, and suddenly a broad swath of warm light hits him from below. It’s a really beautiful sequence.”

During the initial discussions that resulted in the show’s dramatic but realistic visual style, Sakharov had to talk David Chase out of adopting a more mobile camera style. “The scripts deal with the psychological worlds of the characters, so I thought we should go for a mature look, not a restlessness,” Sakharov says. “It seemed right to give the audience the time to see the world we were presenting. That was especially important for the scenes in the psychiatrist’s office, where we used no unmotivated camera movement. I think that type of approach helps the actors claim the attention of the viewers.”

This season, Abraham is using a bit more camera movement, although he’s opted to keep the camera still for Tony Soprano’s sessions with his shrink. “We’re a bit more likely to move the camera to reflect what is going on with the characters, even if they’re standing still,” he notes, adding that the subtle, conservative approach is a far cry from the frenetic camera movement often seen on television these days

Abraham instituted another subtle change for season two’s day exteriors. Sakharov always used a #1 or #2 tobacco filter together with an 85 (and a polarizer where appropriate). “The tobacco filters are a way to tie the exteriors to the interiors by making them a bit warmer,” Abraham notes. “However, I found that in haze, the tobacco filter reacted with the lower levels of fill and went too yellow. For that reason, I’m not using the 85, but instead letting the tobacco filter do my color correction [from tungsten to daylight balance]. It’s a happier medium. Whenever possible, I combine the tobacco filter with a polarizer, which adds a rich, contrasty, feature-look quality.”

During the show’s first season, the tight schedule resulted in an unorthodox yet consistent approach to a key location that deviates from the generally realistic look. The exteriors in front of the North Jersey pork store, where the mobsters gather at sidewalk tables to discuss business over espresso, had to be shot when the sun was blasting the building’s facade. “The blazing sun, the added contrast and saturation from the polarizer, and the use of wide-angle lenses created an almost otherworldly effect,” Sakharov relates. The resulting ambience is the opposite of the moody, shadowy interior lighting that often wraps the characters, but Chase and Sakharov decided to incorporate the look into most of the sidewalk cafe scenes, creating an effective visual analogy for the simultaneously overt and covert aspects of the gangster’s lives.

Shot in Super 35, the show’s A-camera is a Platinum Panaflex; oddly enough, Panavision’s latest model, the Millennium, serves as the B-camera. Abraham explains, “I tend to pull the stops on exteriors, but I do so by adjusting the shutter angle instead of the lens aperture, which allows me to maintain a consistent depth of field. With the Platinum, the way you adjust the shutter is like follow-focusing — you feel it. The Millennium is a great camera, but not for changing the shutter angle, because it’s entirely digital. You can program the changes, but there’s no way to make them on the fly.”

The Sopranos carries a complete set of Panavision Primo prime lenses and two Primo zooms. The short 4:1 17.5-75mm T2.3 zoom and the 11:1 24-275mm T2.8. Thus far, Vision 500T 5279 has been utilized as the primary film stock for both exteriors and interiors, although Abraham has been experimenting with Vision 800T 5289. “The 800T is always on the truck,” he says. “I’ve used it sparingly when I want to go to a really low light level, in those scenes where I’m hoping that whatever is bright in the frame is enough to give us some contrast. The stock has worked quite well in those situations.”

Despite the show’s predetermined visual signatures, tight scheduling and permanently pre-rigged lighting setups, Abraham finds that he is free to be creative on the Sopranos set. “My choices tend to be made on an intuitive level,” he submits. “I don’t have a specified, locked-in lighting plan for any particular place. I decide how to light by looking through the eyepiece. Cinematographers talk about having elaborate lighting plans, but I’ve found that despite all of their pre-planning, they’re usually peering through the eyepiece and letting the look take shape as they’re lighting.”

You’ll find our two-part podcast interview with Sakharov about shooting The Sopranos here.

Click here for more archival stories from American Cinematographer.