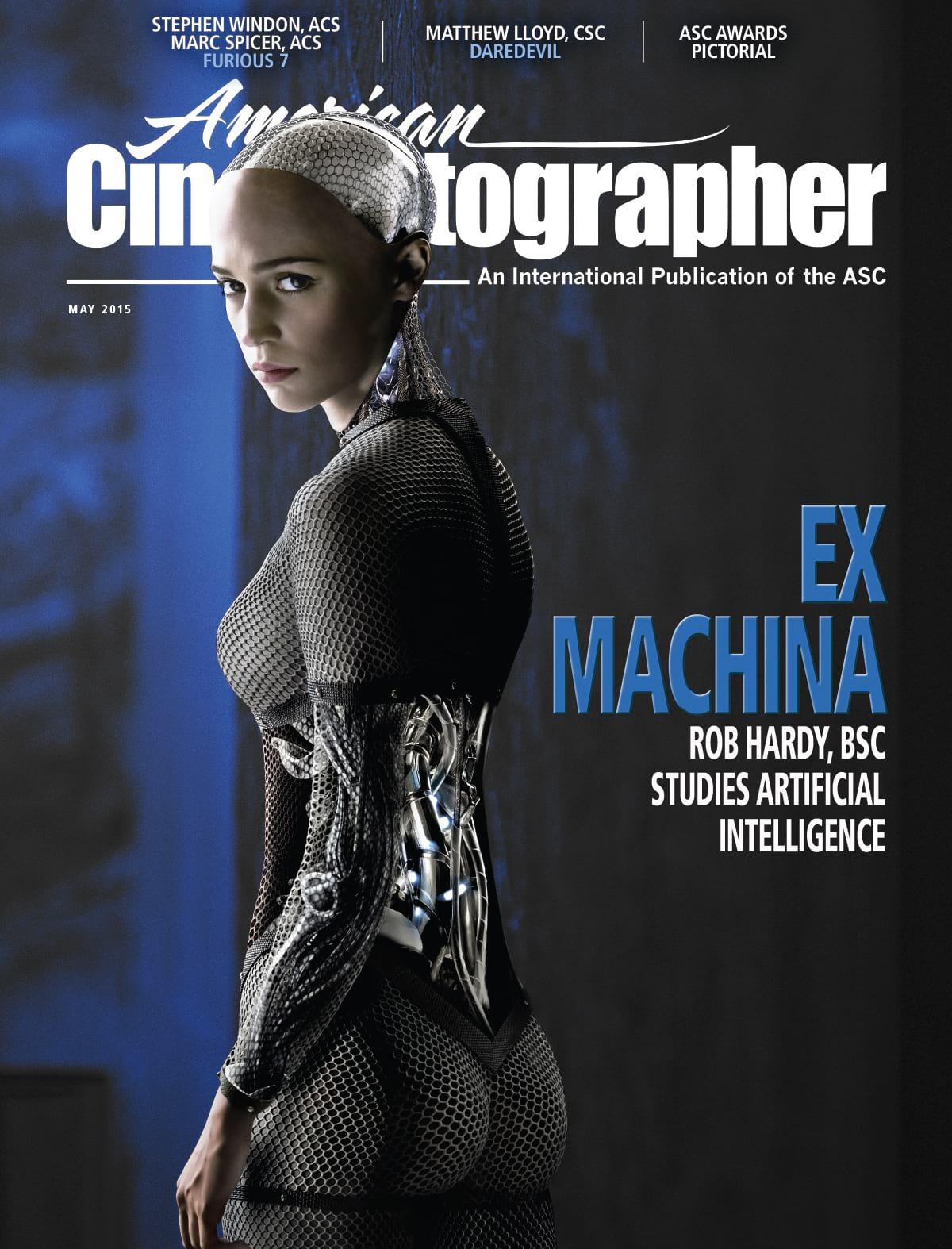

Without Fear: Daredevil

Cinematographer Matthew Lloyd, CSC and director Phil Abraham detail their gritty visual approach to this two-fisted superhero series.

Marvel Comics’ Daredevil character debuted in 1964 as the crime-fighting alter ego of Matt Murdock — a blind New York City lawyer by day and a fearless vigilante by night. Combining his enhanced remaining senses with martial-arts prowess, Daredevil serves as the city’s best defense against evildoers like the nefarious Kingpin.

Marvel recently joined forces with Netflix to develop Daredevil into a series for its streaming service, and Matthew J. Lloyd, CSC was tapped to shoot all 13 episodes of the first season. It was a six-month marathon of New York-based location and stage production that shot from July through December 2014, with the goal of creating a dark and gritty tale that’s decidedly not for kids. (And with an eye on the long game, Netflix is releasing Daredevil as the first of four superhero shows, with the intent to combine them into the crossover project The Defenders.)

Charlie Cox stars as Murdock/Daredevil, with Deborah Ann Woll as Karen Page, Rosario Dawson as nurse Claire Temple, and Vincent D’Onofrio as Wilson Fisk — a.k.a. Kingpin. Veteran cinematographer and series director Phil Abraham (The Sopranos, Mad Men) helmed the first and second episodes of the series, which served as pilot and origin story for the fearless sentinel.

Though he admits he’s not a comic-book aficionado, Lloyd greatly admires the Marvel Cinematic Universe. Furthermore, having acquired a taste for television through his numerous collaborations with director Adam Bernstein, Lloyd says he couldn’t pass up the opportunity to shoot Daredevil. “My agent got me a meeting,” he recalls, “and I went in and met with [executive producers] Karim Zreik and Jeph Loeb. They were looking to create something outside of the typical scope of broadcast. Showrunner Steven DeKnight also said they wanted to really push the boundaries and I was well suited for that kind of a task.”

Abraham says, “I saw Matt’s work on Fargo and thought he was a great choice for Daredevil. He started a few days after I did and we had a very tight schedule with about three weeks of prep. We looked at many of the classic New York street movies for reference and inspiration, like Taxi Driver, Dog Day Afternoon, The French Connection, Marathon Man and Serpico. Daredevil is a modern-day film noir, so I also showed Matt a British vigilante crime film, Harry Brown [AC June ’10]. It has a lot of visceral camera movement and stylistic lighting from sodium-and mercury-vapor sources in a very realistic setting without cinematic romanticism.”

Daredevil shot on location in New York City with stage work at Broadway Stages in Greenpoint, Brooklyn. Netflix’s delivery requirements stipulated a 4K master for both 1080p HD streaming and to accommodate the company’s nascent Ultra HD streaming rollout. “With the incredibly physical reality of an action show, the only 4K option at the time was the Red Epic Dragon,” notes Lloyd. “It had durability, flexible size and reconfigurable modes. I’d also recently done Project Almanac on Red cameras with a similar set of requirements: lots of moving camera, nights, high-speed work and 4K delivery. Panavision New York was able to make a tethered configuration with most of the required gear in a backpack, leaving a compact 10-to-15-pound body, viewfinder and lens that the operators could more easily handhold.”

The Epic Dragons recorded 4K raw Redcode files at 5:1 compression to onboard RedMag SSDs. Lloyd notes that 4K was chosen rather than the 6K that the Epic Dragon is capable of “because we were delivering in 4K. We were also shooting a lot of high-speed [footage], and I didn’t want to be constantly switching resolutions — that can be messy for the post folks.”

camera) and director Phil Abraham (pointing to

monitor) line up a frame with Cox.

Lloyd chose Arri/Zeiss Master Primes to go with the Epics. “I’ve never really encountered another set of lenses as robust, well-made and durable as Master Primes,” Lloyd says. “We had a full range of every available focal length and we were shooting very dark night scenes with a lot of stunts and fast movement. With the bulk of the show shot between T1.4 and T2.0, our ACs were virtuosos at hitting focus under extremely challenging conditions.” The production also carried a set of Angenieux Optimo zooms, including the 15-40mm (T2.6), 28-76mm (T2.6) and 45-120mm (T2.8). Panavision New York provided all of the production’s lenses. Lloyd shot at a 16:9 aspect ratio, mostly handheld, along with some Steadicam, 25' and 50' Technocrane, and 40' Louma Crane work. Key collaborators included Lloyd’s longtime key grip Jim McMillan (who also served as action-unit cinematographer), A-camera focus puller Marc Hillygus, digital-imaging technician Patrick Cecilian, gaffer Rusty Engles and production designer Loren Weeks.

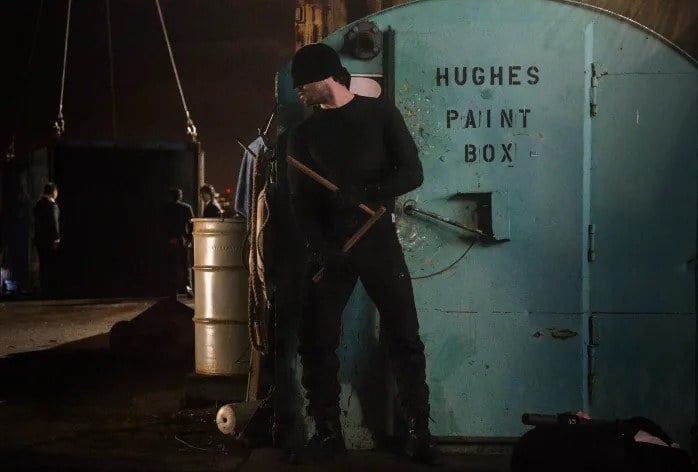

The first episode of Daredevil opens with a major fight scene featuring a shadowy figure battling a series of thugs on a waterfront dock, shot in the Red Hook neighborhood of Brooklyn with a view of Manhattan across the river. “The script has [Daredevil] popping in and out of very deep shadows, pulling bad guys out of the light, knocking them out off camera and then throwing them back out into the light,” Lloyd explains. “I knew we’d get killed if we tried to do localized lighting for all those scenes, so instead we placed huge units very far away. Peter Girolami at SourceMaker custom-built an 8-foot-by-8-foot air-filled balloon cube with two independently controlled 1,000-watt sodium-vapor football globes inside.

“I had the crew frame the cube with speed rail, like a soft box, with an LCD egg crate on the bottom,” he continues. “It was a very soft, directional box that gimbaled off the end of our Jekko crane. The cube included a 5K tungsten globe on a dimmer to help clean up the parts of the color spectrum where sodium vapor peaks. It provided a nice, focused, authentic night light.

“Rusty and his team also ran cables along the rooftops and set up a variety of Arri T12 tungsten Fresnels,” Lloyd adds. “We also had a couple of 60-foot scissor lifts with 12 very narrow-spot Par cans per lift. We used Lee 179 Chrome Orange, 100 Spring Yellow and combinations of Half CTB and Half Plus Green to match the tungsten lights to the industrial vapor units. Phil was also very specific about [the look] being very patchy in terms of what you’d see and not see. So we used the big units to pick up a nice background piece behind the characters and let everything else fall off to darkness.”

“Dark is a subjective thing,” observes Abraham. “Matt and I provided each other with the moral support and confidence against that creeping notion that things were getting too dark. A cinematographer needs to feel empowered to go for it and be daring, as that’s how great things are achieved. With film you also have the doubt of not knowing exactly how underexposed you might be, but shooting digitally, everyone is seeing the image on the monitor.”

Throughout the first two episodes, flashbacks portray Murdock’s childhood as he slowly goes blind, braving the ordeal accompanied by his father, a morally upstanding professional boxer. The production chose a compact, split-level “railroad” apartment with narrow hallways in Queens to represent the hero’s childhood home. “It was the smallest set we had to work with by far,” Lloyd says. “We tried to do as much as possible through the windows and via motivated sources. We removed all the fixtures from the ceiling and wired everything through existing house power to avoid cables, crossovers and boxes. Inside, we built covered wagons with skirted, unbleached muslin and batten strips of four to eight household sockets with a variety of globes to produce a slightly uneven soft source.

“To augment the overheads, we added SourceMaker 2-foot-by-2-foot LED Blankets in closets and washing down stairways,” he adds. “Outside the apartment, we horizontally mounted [Kino Flo] Image 85s gelled [with] Industrial Green aiming onto the flat blinds that the art department added. The set also had a lot of practicals and a Kelvin Tile LED fixture to simulate the modulated wash from a TV as Matt watches his dad boxing. It was our best attempt at a Gordon Willis [ASC] look — with everything very dark and motivated.”

Abraham adds, “We liked the idea of being mostly handheld in present time while the flashbacks could be a little more rooted on traditional dollies or a crane. I had a lot of reticence about filming in an actual apartment due to the size, but it really made the relationship between father and son resonate.”

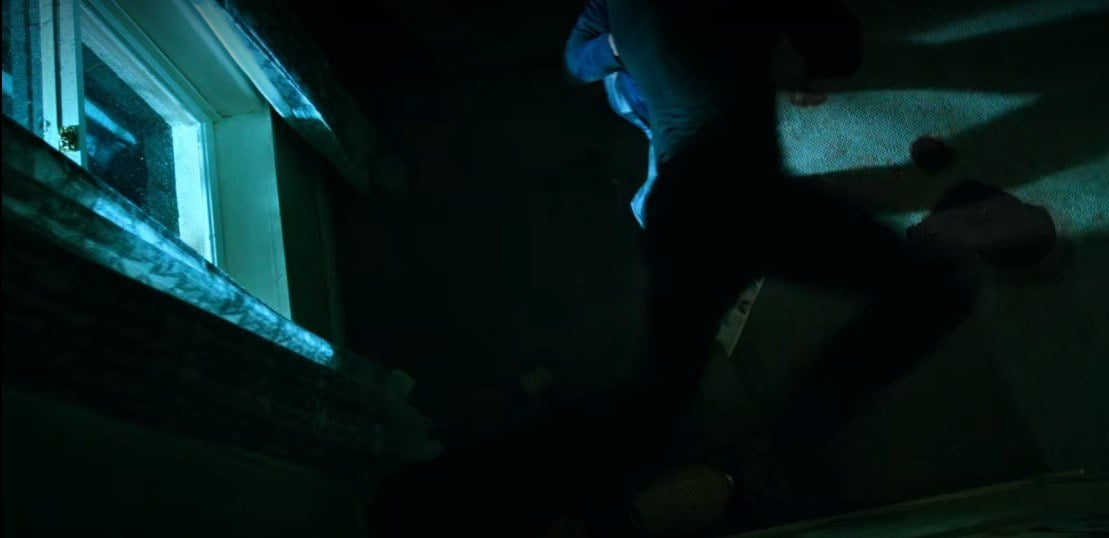

Another key fight sequence ends the first episode, as Daredevil defends Karen Page from assassins at her apartment. “It was a running fight that goes from a studio set of Karen’s apartment, continues down the side of a building on location, and ends up at a construction site nearby — all in pouring rain,” Abraham explains. “We shot some parts of it at 96 fps to heighten the action; anything higher than that becomes eye candy.”

“That was the darkest scene of the series and the darkest thing I’ve ever shot,” notes Lloyd. “We started in Karen’s apartment with people fighting in the dark against windows. There was a heavily diffused Arri T12 with a mercury-vapor gel pack on the front above each window creating pools of light and long bay lights with household bulbs dimmed to just above zero IRE inside.

“Next, the fight moves outside onto a scaffolding that Loren built both into the set and onto the real building exterior to bridge the two locations,” the cinematographer continues. “The scaffolding included practical overhead fluorescent lamps combined with 4-foot two-bank Cool White Kino Flos wrapped in diffuse plastic. Across the street, we used Arri M90 lightweight 9K HMIs with Max reflectors to create a huge overall wash.

“The fighting continues at a construction site,” Lloyd adds. “We brought back in the SourceMaker mercury-vapor cube from the opening scene, along with pairs of M90s in a 120-foot Condor on the other side of the block. Everything ended up incredibly high up in the air due to all the rain towers in play. They were at 60 feet, so we had to put our lights at 80 to 100 feet to keep them dry. There was so much second-unit work on those fight scenes — Jim’s contribution as our second-unit director of photography cannot be overstated.”

To depict Daredevil’s signature heightened perception at key moments, Lloyd chose an old-school optical approach. “We used a Century Optics Swing/Shift system,” he reveals. The system, Lloyd explains, included “rehoused Hasselblad lenses; you adjust the tilt and pan of the focal plane by sliding [and/or tilting] the lens itself away from the sensor. It was like making a daguerreotype, with the actors holding very still as I adjusted dials and the bellows. You end up with a shot where you have very shallow focus, say on Daredevil’s eyes, and then some important detail very far off in the distance and nothing else. [The effect is] like a variable split-field diopter.”

A final major fight scene, which bookends Daredevil’s second episode, is a nearly six-minute-long continuous take. The camera follows Daredevil as he fights his way through successions of baddies in a basement hallway to rescue human-trafficking victims. Once the creative team signed off on the concept, it was up to Abraham and Lloyd to practically achieve the shot.

“The idea, subconsciously or not, probably initially came from the extended, single-take fight sequence in Oldboy,” notes Abraham. “Otto Preminger also used a lot of long, languid takes in Where the Sidewalk Ends and Laura. It adds real tension to the performances because you’re witnessing something unfold from a single point of view. You’re dealing with the pressures and tensions of a long single take and adding a fight, with 10 to 12 guys from Chris Brewster’s stunt team going full-on in a very narrow hallway set.”

“Initially, Phil suggested it could be done on Steadicam or perhaps with moving set walls,” says Lloyd. “I worked with Loren and Jimmy to devise another option: build a very rigid set with a scaffolding shelf, reinforced by water drums, and on top an I-beam bridge with a rail dolly system that held A-dolly grip Dan Beaman and a Fisher 10 dolly. The ceiling had a 1-foot channel for an underslung Epic on a Mini Libra head. Rigging key grip Dave McAllister engineered the scaffolding system that supported the set and Jimmy built the I-beams spanning the set, enabling the dolly to roll overhead on an offset riser. High-tension wire was added to reinforce the walls and prevent any flexing or wobbling as the dolly maneuvered above the action.”

scene with director

and executive

producer Steven

DeKnight.

With the physical configuration solved, the next hurdle was lighting the narrow space as the camera made multiple 360-degree turns. “The set was built as a real hallway with no lighting positions and nothing wild, so it became a strategic practical situation,” Lloyd explains. “The hallway featured two side rooms, each with two dead-hung Image 85s with Cool White fluorescent bulbs lighting the room and pushing out into the hall. As Daredevil busts into the rooms and rips the doors off the hinges and fights, you get shafts of light coming out of the rooms. “The hallways on either end had open-faced 2K Blondes bouncing into 4- foot-by-8-foot foam core, creating a soft rake at 90 degrees to the wall to bring out the texture Loren built into the walls,” he continues. “The room at the end also had a 2K Blonde gelled Primary Red to foreshadow Daredevil’s signature costume. It was an Expressions DMX dimmer-board dance, because when you spin around with a suspended camera you can’t have a light on behind you or you’ll see the camera shadow on the hall and on the actors.

“We had a 100-watt frosted household bulb mounted at 90 degrees on the side of the wall right at the front entryway and a fluorescent housing over the door at the back fitted with a Mac Tech LED tube,” Lloyd adds. “That enabled a smooth ramp from 0 to 100 percent on both the fluorescent and incandescent units at either end of the hall. Our board operator, Jim McNeal, looked like he was playing a perfectly timed game of Pac-Man, riding two faders as the camera panned up and down [the hallway]. It’s a really incredible sequence to watch when you think about all the mechanics, and yet the moviemaking is completely invisible.” Lloyd chose to operate the complex move himself, which the crew nailed in a single day in seven takes after plenty of rehearsal.

Colorist Kevin Krout supervised most of the series’ dailies at Encore in New York after taking over for Rob Bell and Lloyd’s longtime colorist, Andrew Geary. Lloyd communicated his desired look for specific scenes by grading stills in Photoshop on his laptop. “We punched out a pretty unique look for the show,” recalls Krout. “I’d take the raw 4K Red R3D files into my system via Encore’s SAN, apply a LUT that Matt created previously for use with Red Epic shows, and color dailies based on Matt’s stills.

“From the graded dailies, we delivered Avid DNx36 1080p files,” Krout continues. “We also uploaded H.264 QuickTime files at 720p to the Pix dailies review system. We usually received raw footage from the production between 10 p.m. and midnight and had to deliver dailies by the next morning.” Krout’s hardware included a Pioneer Kuro plasma monitor in one of Encore’s calibrated rooms and a Red Rocket-X PCI card to help speed the processing of R3D files.

“We’re at a strange point where many productions seem to ignore the role of the DIT and dailies,” Lloyd notes. “They just apply Rec 709 as a preset and figure it all out in post. I think doing it that way takes away some consistency and diminishes the process. It is much more cost- and time-effective for production to get the look there in the dailies; it greatly reduces the amount of heavy lifting required in the DI.”

Senior colorist Tony D’Amore at Encore Hollywood supervised the final grade for every episode of the season. He worked with DaVinci Resolve 11 using DPX frames derived from the original Red R3D files with the Redcolor3 preset applied during the transcode. “I’d start with Kevin’s CDLs and Matt’s LUT and initially duplicate what they’d done in dailies,” explains D’Amore. “The looks Matt created were a great way to set a consistent deep, dark tone for the show. I also know what Matt likes from our work together on Fargo. The end result was a gritty, distinctive look. We kept a lemon-lime color palette, with subtle skin tones for a subdued, surreal environment. I balanced everything toward green, combined with Matt’s amber or yellow source to achieve skin tones that were just under key and not super poppy.

“What’s nice about grading with Resolve is that I can color inside of a LUT, versus other systems that do not allow me to modify the parameters of a LUT at all,” D’Amore adds. “For example, in some shots lit by an exterior source, the initial LUT clipped the highlights. I was then able to open the input LUT and lower the white levels to bring back detail from shot to shot. I’m not a big believer in LUTs, although they can be very helpful as a starting point and to maintain the attributes of the Red capture.”

As the grades were completed, Lloyd was able to review D’Amore’s work remotely while he shot further episodes. “We’d often stream directly from Encore Hollywood to a suite at Encore in New York for Matt,” says D’Amore. “All the gear and monitors in both locations are calibrated the same.” Executives from Marvel and Netflix screened final versions for approval with D’Amore on a Sony XBR-65X950B 65" Ultra HD monitor in 3840x2160 resolution via a Blackmagic Design Mini Converter. Final deliverables included 4K DPX masters along with Rec 709 1080p down-conversions.

Abraham views the Netflix concept of releasing all episodes of a season simultaneously as the way of the future. “It’s brilliant and the only way to do it,” he says. “When Netflix first started this distribution model, I worked with them on Orange Is the New Black. It’s very viewer-friendly; you watch as much or as little of an entire season whenever you want.

“As a filmmaker, I find [that the simultaneous-release strategy] does present some unique challenges, and you need to consider the different modes of consumption,” Abraham adds. “What you do at the end of episode two could be followed immediately afterwards by someone watching episode three. So, for example, you have to be really careful about reusing locations, because you don’t have that weeklong viewer memory lapse to fall back on. But overall, I think every broadcaster should do it this way.”

Similarly, Lloyd sees challenges and benefits in shooting every episode of an entire season. “Normally, I don’t do full series,” he says. “I generally stop after the first couple of episodes and hand off to another cinematographer. To see an arc through 13 hours of moviemaking, and then feel as great about the last hour as you do about the first, was a fulfilling journey.

“It was also incredibly hard for the crew and me, but ultimately very rewarding,” Lloyd continues. “I give a huge amount of credit to Marvel’s creative team for backing what we set out to do. It’s easy to say, ‘We want something dark, sinister and adult,’ and then dumb it down to a ‘PG’ level. They really went the distance, from the stunt sequences to the look and even the casting. Throughout all of it, everyone really believed in what we were doing.”

Lloyd became a member of the ASC in 2020.