The Testament of Ann Lee: A Modern Baroque Approach to Faith, Movement and Film

The historical-musical epic's cinematographer shares insights on his visual strategy, as well as two scene studies and commentary from key crewmembers.

The Testament of Ann Lee stands as one of the most meaningful projects of my career.

Reuniting with director Mona Fastvold, alongside an extraordinary cast led by Amanda Seyfried and deeply committed crews across Hungary, Sweden, the United States and England, was both creatively rigorous and deeply rewarding. From the outset, the production demanded ambition: a period film shot on 35mm in just 34 days, on a modest budget, and structured as a musical. Under those constraints, the film would not have been possible without Mona’s clear cinematic vision and the unwavering dedication of the cast and crew.

Developing the Visual Language

Months before production, Mona and I met frequently to define the film’s visual identity. Many of these conversations unfolded over long meals with production designer Sam Bader, as we searched for a language that felt historically grounded, yet emotionally immediate. Music became a foundational element early on. We immersed ourselves in Shaker hymns and early compositions by Daniel Blumberg, allowing the soundscape to guide rhythm, tone and restraint.

Rather than leaning on traditional film references, we turned to painting and photography. We looked to Caravaggio for inspiration — particularly his use of shadow and sculptural light to reveal character and emotion. The quiet, introspective interiors of Vilhelm Hammershøi offered a model for stillness and restraint. Bill Henson’s photographic work, particularly Mnemosyn, influenced our embrace of darkness, texture and ambiguity.

Out of these influences emerged what we described as a "modern Baroque" approach. We intentionally avoided conventional film lighting, choosing instead to light environments organically. Candles and daylight served as our primary motivators, allowing the light to feel discovered rather than imposed. Shadow, falloff and imperfection became expressive tools rather than problems to be corrected.

Format, Film Stock and Capture

We briefly considered large-format capture, but ultimately selected 35mm Arricam LT and ST cameras. Their compact size and reduced noise profile proved essential, particularly because live singing was recorded on set. A quiet camera allowed us to place the lens mere inches from an actor without compromising sound.

After testing more than 10 sets of prime lenses, we chose Sigma Cine and Sigma Classic primes for their balance of clarity and softness, and for how naturally they rendered faces in period environments. We shot Kodak Vision3 250D 5207 for day exteriors and interiors, and Kodak Vision3 500T 5219 for low-light and night sequences.

Processing, 2K dailies and 4K select scans were completed at Focus-Fox Studio in Budapest. Background plates were hand-painted by matte artist Leigh Took of Mattes & Miniatures Visual Effects in London. Colorist Máté Ternyik and I completed the DCP grade in London, after which the final film was blown up to 70mm and graded at FotoKem.

Music as Narrative Engine

Music has always been central to my life. I grew up around it, with a father in the music business, and my earliest jobs involved running follow-spots for artists like The Spinners and Earth, Wind & Fire. Later, I shot music videos for artists including Bruce Springsteen, Beyoncé and David Byrne, and collaborated with Baz Luhrmann on The Get Down.

Yet, The Testament of Ann Lee is not a traditional musical. In our film, movement emerges from prayer rather than spectacle. The dances function as spiritual expression, rooted in devotion and communal belief. That distinction freed us from cinematic musical conventions and allowed us to invent a visual grammar grounded in faith, restraint, and interiority.

Scene Study: “All Is Summer”

The Shakers gather on the deck of a ship during their Atlantic crossing.

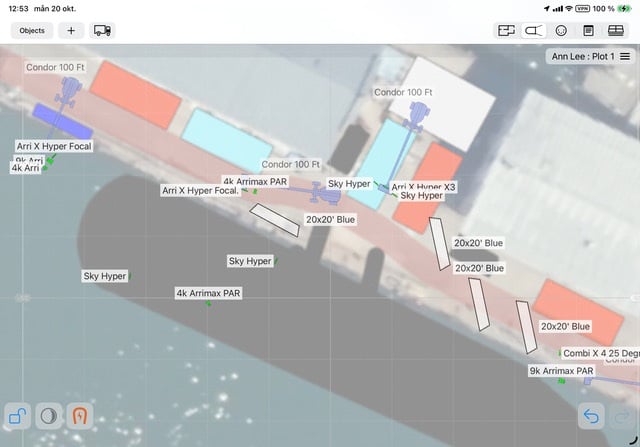

The dance sequence aboard the ship was among the most demanding and rewarding scenes to design and execute. Months before production, Mona and I began working with choreographer Celia Rowlson-Hall in New York. After Sam Bader identified a potential ship, we obtained deck dimensions and taped out the space in a Lower Manhattan dance studio.

Using the Artemis app, we recorded extensive rehearsals, studying angles, movement and aspect ratio. Our guiding principle was that the camera should behave as one of the Shaker religion's believers. To achieve a sense of immediacy, we committed to handheld operation and wider lenses.

This approach proved invaluable once we arrived on the actual ship, where space was severely limited. During rehearsals, we also discovered that the 2.39:1 aspect ratio best supported the dancers’ formations and spatial relationships.

I previsualized the entire sequence and shared it with Sam Ellison, our A-camera operator and 2nd-unit cinematographer. His intuitive understanding of movement made him an essential collaborator, and we shared operating duties throughout the sequence. With the exception of a single overhead shot rigged from a lift during rain, the entire sequence is handheld.

Lighting the Ship — Gaffer Jonas Elmqvist Reflects on the Challenges of the Göteborg

Elmqvist: "I received a call from a stressed Swedish producer to jump in for a one-week gaffer job on the ship Göteborg. I said yes before fully understanding the scope. We had a single prep day to portray three months of Atlantic sailing over three shooting days — sun, storms, snow, heavy rain, interiors and moments of dance and song — all while the ship was docked in Gothenburg, standing in for the open Atlantic of the 18th century.

Lighting a 75-meter vessel with limited crane access demanded careful planning. With five cranes, movers and a mix of M90s, Arri X units, Dino Lights and Astera fixtures, we moved quickly and stayed flexible. All LEDs were controlled via grandMA, both for interiors and lightning effects.

It was an intense and joyful few days, a reminder of what filmmaking means to me — like when I started as an electrician 40 years ago. Pressure, collaboration and craftsmanship came together perfectly. The keys to success were clear: shared vision, exceptional professionals at every level, open communication, and proper prep. When a real storm rolled in on day two, we seamlessly shifted to interiors prepped as cover sets. Shooting on film brought a focus and depth unlike digital work."

Scene Study: “Hunger and Thirst”

Ann Lee sings alone in a prison cell.

While much of the film was shot single-camera, the prison-cell sequence stands apart in its simplicity. Confined to a small, filthy cell, Amanda Seyfried delivers a devastating performance. Gaffer Zoltán Gecco Kristóffy and I placed a single 10K Molebeam on a dolly track outside the window and slowly moved it over the duration of the scene to evoke the passage of sunrise.

The entire three-minute song unfolds in a single take. Amanda, Mona and I rehearsed extensively, timing every beat with precision. It remains one of the quietest, most intense sequences I’ve ever shot, and one of the purest expressions of our shared intent.

A-Camera Operator and 2nd-Unit Cinematographer Sam Ellison on Trust and Improvisation

Ellison: "One shot stands out for me — a handheld oner covering the entire song ‘Hunger and Thirst,’ with Amanda performing on the hay-covered floor of a cramped jail cell. On that day, I felt an incredible sense of unity with Mona, Will, and Amanda, which epitomized the spirit of collaboration on set. We had no rigid plan; the environment was set for improvisation, and my job was to react. Subtle adjustments, rising and falling with the action, hovering about two feet from Amanda’s face — that trust made the sequence work.

Each take ran nearly a full magazine of film, and during reloads, Will and I made a few almost unspoken adjustments. When the Molebeam sunlight finally rose into the window near the song’s end, it felt genuinely miraculous, matched by the depth of expression in Amanda’s eyes. Watching the finished film on a big screen, I grinned uncontrollably — maybe whispering ‘don’t cut’ under my breath. I don’t think I’ve ever felt so connected to a single shot or to the core creative collaborators on set.”

In the end, The Testament of Ann Lee was an extraordinary exercise in trust, improvisation, and precision. From the deck of a ship in Gothenburg to a solitary prison cell, every scene demanded careful orchestration, yet allowed for spontaneity. For me, the final result reflects not just the story on-screen, but the dedication, intuition and artistry of every member of the crew.

Images courtesy of Searchlight Pictures and the filmmakers.