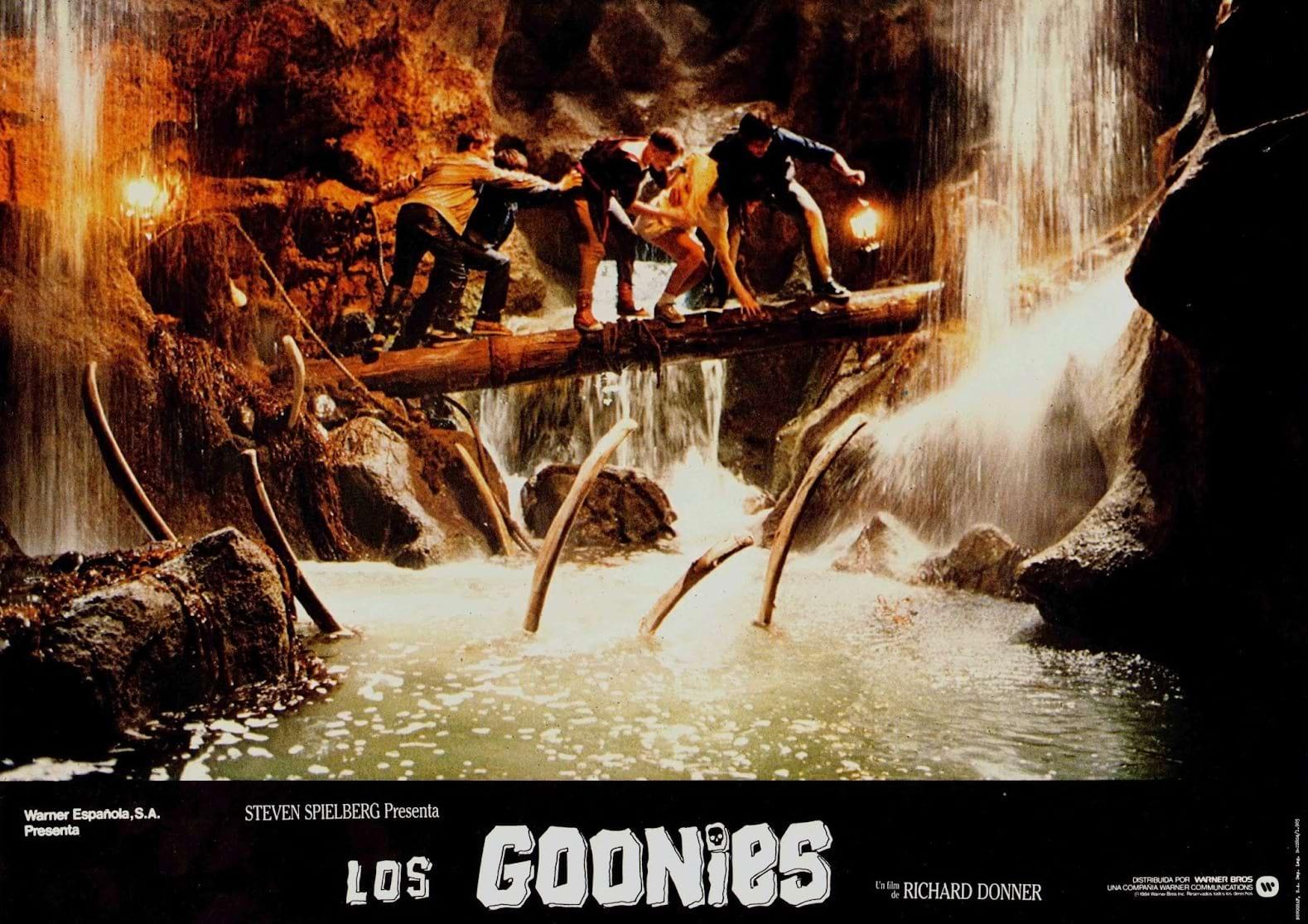

Underground Wonders for The Goonies

A closer look at how ILM delivered One-Eyed Willy’s pirate ship for this imaginative adventure.

This article originally appeared in AC, Dec. 1985. Some images are additional or alternate.

Industrial Light & Magic, the special effects facility of Lucasfilm, Ltd., achieved high rank in its field through its superb work in Lucas productions. More recently it has branched out to do work for other production companies, also with great success. One recent film which contains some striking contributions from ILM is The Goonies, a Warner Bros release presented by Steven Spielberg and produced and directed by Richard Donner.

This action show maintains a fast pace while depicting the adventures of seven youngsters — a sort of Our Gang for the ’80s — who are searching for treasure while fleeing a family of gangsters in the tunnels and caves beneath an ancient seacoast inn.

Two of the key men involved in the visual effects of The Goonies, ILM general manager Warren Franklin and supervisor of special effects Mike McAlister, discussed the project with American Cinematographer.

“When a script comes in we try to keep an open mind about what things we might be able to do and really look at it from a lot of different perspectives,” Franklin said. “It’s an advantage that we have five different visual effect supervisors who offer a lot of different approaches. We try to get everybody together and say, ‘Here is the film and what are the different things we can do on it?’ and then we try to come up with something that satisfies the budget requirements as well as what would work best for the particular film. Sometimes those aren’t the same thing and we try to balance them out. We try to keep an open mind as to how simple or complicated it needs to be. We like to use bubble gum and coathangers if they’ll work. Sometimes they need the latest technology and we’re certainly trying to keep very active in that.

“There are things a writer will imagine that couldn’t be done any other way, places they want to go that don’t exist, things that are out of this world or full of the fantastic.”

— Warren Franklin

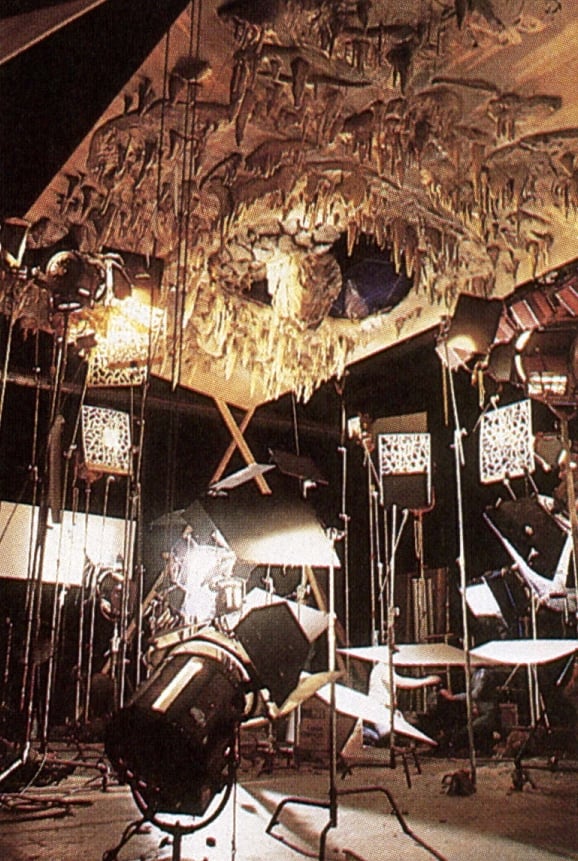

“In the case of Goonies, they had such a short post-production schedule that it became obvious up front that we needed to build as much practically as we could because going the route with miniatures and so on would have taken a lot of time we didn’t have. Therefore, the production designer, J. Michael Riva, tried to build everything he could. The pirate cavern and ship were built at The Burbank Studios and then we augmented them with matte paintings and miniatures to make them seem even bigger than they were. Mike Riva did a great job.”

Franklin pointed out that the approach is almost opposite to what was done with Indiana Jones. “It’s just a question of deciding what’s right for a particular film instead of saying that just because we did it in Indy we should do all the underground stuff in miniature on Goonies. One must look carefully at the schedule and the budget and all other considerations. It may mean saying we’ll just do a few matte paintings on this show as opposed to making it a huge special effects movie. That kind of versatility pays off. We’re not giving anybody any more than what they need. We let the producer and director figure out what’s right for their film and then we help them out. George Lucas’ whole philosophy is to have a full-service film company where people can come in and the number-one priority is to make good movies.”

Mike McAlister, who was director of photography for the special effects of Starman, graduated to supervisor of visual effects on Goonies.

“Goonies, as it turned out, was quite a small project compared to what we’re used to,” McAlister recalled. “Although I did have to have camera crews doing a lot of the shooting, I was actually able to do a lot of hands-on stuff. It’s real fun for me because it takes care of my creative urges — I get to express myself that way, and also get to use my hands working with technical solutions to problems. I started at USC as an engineering major and switched over to cinema after two years. I’ve used everything I learned in engineering here at one time or another.”

McAlister and his crew shot background plates at The Burbank Studios and on location in Oregon. “On the stages in L.A. we were sort of a third unit that followed everybody else around and tried to match lighting in it all,” McAlister said. “We got our plates on the stages there and then came up here and, in some circumstances, tried to put a pirate ship into the place that we had photographed down there.

“They had built a pirate ship from the masts down and it was incredible! It was worth being on the movie just to see that set. The sails and the rigging were painted in, as was the top of the cavern and the upper half of the cavern walls. The matte department — Chris Evans, Frank Ordaz and Caroleen Green —painted all that stuff. I served as the liaison between the director and the matte department.”

Chris Evans said that the matte work was minimal in Goonies. “Just a few shots that needed a little paint in them, fill in the gaps, that’s all there was.”

McAlister described one sequence which utilized some unusual techniques. “A stick of dynamite goes off, some booby traps are released and the cave starts collapsing. We built a wall about 18 feet tall, made out of foam with urethane foam sprayed on the back. With very light glue and plaster we mounted rocks all over the face of this cliff, so that when we’d beat on the back side all the rocks would fall off. We shot it at high speed and added some smoke and light flares and such.

“That was combined with the big set, which was another background we’d shot at Burbank. What we finally did was just remove the wall of their set - the cave wall — and replace it with our miniature. It was probably the most complicated shot in the movie for us. When the rocks splashed in the water, that was the real water in the big set. We had the practical effects people down there submerge air cannons right below the water, and when they’d shoot those off it would create a big splash. Everywhere there was a big splash we’d choreograph it in advance. We would put a rock falling into it and halt printing on it or put an articulate matte edge on so it would appear to submerge into the water with a big splash.

“When you’re shooting a set with the intention of replacing part of it, you can’t have any foreground objects passing in front of the part you’re going to take away, because then the foreground object would be taken away as well. If something splashes in front of the wall you’re trying to get rid of, when you get rid of the wall you’ll also get rid of the splash that covers the wall. Then you have a splash that starts nicely and suddenly it gets cut off! So, we weren’t able to put as many splashes into the plate when we photographed it as we knew we would end up wanting. Once we’d finished photographing it with all the actors, we set up in the water and turned off all the lights on the stage except two, to light an area of the water where we’d have these generic splashes go off. We shot them full frame, reduced them later and just placed them wherever we wanted to in the frame.”

Bruce Walters, of ILM’s animation department, described the painstaking method used to time the “falling” of the rocks: “They tried to shoot the rocks on stages, but they were using foam rocks and when they fell they would practically float down,” Walters related. “So Charlie Mullen, head of the animation department, went to the stream behind his house and selected a number of rocks averaging about two inches in length. He drilled holes in them. Then he rigged up a deal on the animation stand so that he could photograph the rocks. He put a motor into the hole in the side so he could rotate the rock and photograph it to get the move of it falling. He was shooting down and the rock moved from the top of the frame to the bottom as if it was falling. Then we rigged a blue screen on the animation stand and we shot all the rocks, one at a time, that way. We match-moved the fall so that when the splash they created on the set happens the rock would be in the right place.”

McAlister described several shots in which the pirate ship escapes from the cavern and people on shore watch it sail out into the sea.

“One of these shots that I thought turned out well was of the ship passing behind some rocks as it leaves the coast and heads out to sea. It is nice and hazy, but it was a terrible thing to accomplish. We tried over and over again to get it composited.” The difficulty, he explained, was in getting the ship to “stay back there” beyond the rocks. “It’s these subtle, hazy atmospheric conditions that really make our work difficult. When you take a hazy scene and try to matte something into it, whatever you’re matting has to be hazy as well. It’s very difficult matching the atmosphere of the two elements. John Ellis, who did the optical work, did an exceptional job on those shots.”

Bruce Walters recalled that the departing ship was “just a transparency of a model. We overlaid the rocking motion of the sea into it with a special computer program. We got the program by match-moving actual footage of a ship on the water. We got the main bulk of the model from one place to another with the transparency. Then we just added in the rocking motion — the camera does the rest.

“The transparency was of the whole ship, so we took pieces of paper and ripped them along one edge and mounted them on opposite peg boards and moved them across the bottom of the ship. This created the waves lapping on the bottom of the ship, so when the mattes were done it had that element in it and all we had to do was to stick it in the frame and it gave the illusion that the ship was sitting in water.”

Another complex sequence occurs when the youths are being chased by the villains and they run into an organ chamber. The only way to escape across a chasm is to play an organ made of bones. With each correct note, the drawbridge comes down a bit, moving closer to bridging the gap. Each time they play a wrong note, a piece of the floor falls out from beneath them.

“We did some shots there of the floor falling away into oblivion, a big cavernous opening below with stalactites and obvious danger and death,” McAlister said. “Again, we shot the foreground plates with the action in Burbank and brought that film up here and designed the floor pieces that were supposed to fall away. We built them to match what they had in the practical set but in about one-third scale - the three-foot rocks were one foot across. We took those up to the top of our stage ceiling and dropped them into the reflective blue screen.

“We started out matting those in over matte paintings so that when the floor pieces dropped away there was nothing there but the stage floor and we did a matte painting to extend the hole so that it looked like it was going down to infinity. It was quite a tough scene to accomplish, and we went round robin for quite a while trying to come up with a concept of what was supposed to be below the floor that could tell you instantly, in a 24-frame cut, that it was death down there. It had to work almost subliminally.

“We toyed around with that for probably six weeks before we came up with something that was permissible. Ultimately we used not a painting but a miniature. We got some fog and smoke effects down there to give it a little bit of life. It was built on a miniature floor that was about 16X10 feet, and that was supposed to be something that was maybe a half-mile wide. As a general rule, the larger you can build miniatures the better off you’re going to be, because you have more of an opportunity to add detail. It’s especially so if you’re working with smoke or water because you can’t miniaturize water. There are certain kinds of smoke that can be worked pretty well in miniature, but there’s a certain point beyond which they can’t really be used.”

The visual effects of Goonies are a part of the stream of fantasy effects for which ILM has gained renown. The company also is moving into a much-neglected area, that of creating visual effects that enhance realism. Warren Franklin expressed the idea shared by the artists and craftsmen who make it possible:

“Part of our job is to educate filmmakers as to what we’re able to contribute to their films, and that it isn’t necessarily a spaceship or an alien. It can be a mine tunnel or a hallucination or just adding a storm cloud and lightning to make the scene look better. People are beginning to understand that we can do a lot more than we have done and that we can do things a lot cheaper in many instances than they might be able to do practically, and more effectively as well. We have to keep pushing the field forward, to be working on more than just big-budget space movies or things that are obviously special effects. George Lucas is certainly interested in that. He looks at visual effects as just another tool in his filmmaking toolbox. He’ll use a matte shot just as easily as someone else will use a dolly move, because he knows he can do it a lot less expensively and get a lot more production value from a painting that’s done right than by going out and building a huge set or going halfway around the world on location.

“There are things a writer will imagine that couldn’t be done any other way, places they want to go that don’t exist, things that are out of this world or full of the fantastic. And then there are things that are much more vivid when done with special effects — like the mine chase in Indiana Jones [and the Temple of Doom],” Franklin said. “We look for stories and scripts that we can contribute to that are different and have things in them that people wouldn’t expect us to be working on. That’s where the future is and we want to be there.”

Former Oakland Raider defensive lineman John Matuszak played the role of Sloth under heavy prosthetic makeup. He, unfortunately, passed away just a few years later at the age of 38, before he could really see the lasting impact and cult status that both the movie and his memorable character would achieve.

If you enjoy archival and retrospective articles on classic and influential films, you'll find more AC historical coverage here.

Access the every issue of AC and every story from more than the last 100 years with our Digital Edition + Archive subscription.