Visions of Grandeur on The Big Trail

The Big Trail, shot by ASC founding member Arthur Edeson in the 70mm Grandeur format, turns 85. (Now 95!)

This article originally appeared in AC April 2015. All images courtesy of the Margaret Herrick Library.

It was the movie that made John Wayne a star — and nearly ruined his career. It was the most ambitious Western of it's time — and nearly ended the genre for good. It’s a movie about which everything was genuinely big, from its 70mm Grandeur cameras, to its payroll of 20,000 extras and five separate casts, to its epic behind-the-scenes tales of Prohibition-era carousing. It was director Raoul Walsh’s sprawling, rambunctious 1930 feature, The Big Trail, and nothing about it was small — including its legacy.

As The Big Trail celebrates its 85th anniversary this year, it’s worth looking back at this hugely innovative film that not only transformed the young Marion Morrison into John Wayne, but set a new course for cinematography and movie exhibition — even if that path would not be revisited for years to come. Indeed, The Big Trail was the granddaddy of all widescreen epics, the forefather of today’s Imax and 3D extravaganzas, and the first Hollywood production designed to compete with the nascent medium of television. And yet, despite its many innovations, The Big Trail may be the most important Hollywood film few people really know about.

Everything new about The Big Trail — including its 70mm imagery, higher-fidelity sound, and John Wayne — would prove its appeal in years ahead.

Written by former trapper and surveyor Hal Evarts, The Big Trail offers a window into the American frontier, both real and imagined, as it tells a rough-and-tumble story of settlers and outlaws blazing a pioneer trail from Missouri to Oregon’s Willamette Valley. Along the way, the travelers — led by tough young trail scout Breck Coleman (Wayne) — fight the elements and each other, while encountering warring Native American tribes and herds of stampeding buffalo.

Neither Walsh nor his cinematographer, Arthur Edeson, ASC, were strangers to innovation. A co-founder of the American Society of Cinematographers in 1919, Edeson had teamed up with Walsh for the special-effects epic The Thief of Bagdad in 1924. Edeson photographed the thriller The Lost World, with stop-motion effects by Willis O’Brien, the following year, before he and Walsh reteamed for 1929’s In Old Arizona, Hollywood’s first outdoor sound Western. For that production, Edeson experimented with camouflaging microphones — a vital technique in the early sound era — and earned his first Oscar nomination. None of these challenges, however, could have fully prepared Edeson for the biggest new thing in cinematography circa 1930: Grandeur.

The Fox Grandeur camera, also known as the “Mitchell FC” (Mitchell Fox camera), was the mad, unwieldy creation of studio mogul William Fox’s engineers. Running a newly devised 70mm, 4-perf version of the 1928 Eastman Type II Cine Negative Panchromatic film, the hefty cameras more than doubled the width of conventional cinema images (48mm versus 21mm in actual image width) and featured a bold 2.13:1 aspect ratio. They also left more than twice the usual amount of film space for an optical sound track (.240 mils versus .100 mils), a vital advantage in the new sound era.

William Fox had conceived the Grandeur system to revolutionize the cinema. With astonishing prescience, he had predicted the threat of broadcast television to Hollywood as early as the late 1920s, reasoning that audiences wouldn’t pay to attend movies if they could watch entertainment at home for free. His solution was simple: go big. As Fox would tell Upton Sinclair (in the 1933 book-length interview Upton Sinclair Presents William Fox), “I reached a conclusion that the one thing that would make it possible to compete with television was to use a screen 10 times larger than the present screen, a camera whose eye could see 10 times as much as at present.”

It was the same solution Hollywood would adopt in the 1950s with such formats as Cinerama, Todd-AO and CinemaScope, and later with Imax. “William Fox saw the threat to the movie industry even then,” says John Hora, ASC. “And he put his money where his ideas were.”

One of Fox’s Grandeur cameras can be seen on display at the Hollywood Heritage Museum; another, in more complete condition, was shown to AC by private collector Richard Bennett. Seen in person, what immediately stands out about the Grandeur is its enormous size. With a fully loaded 70mm magazine, it’s easy to imagine the Grandeur rivaling later 15-perf Imax cameras for sheer immobility. A Grandeur shoot would not move quickly.

For Arthur Edeson’s purposes, however, the most pressing aspect of Fox’s Grandeur cameras was their need for high-quality lenses befitting the extraordinary image resolution of 70mm film. Writing about The Big Trail (AC, Sept. 1930), Edeson noted, “Even though the lenses I used were the product of what is probably the most efficient and exacting optical firm in the world, I found that I had to test at least ten or a dozen individual lenses to obtain one which met all of my tests perfectly.” In the same article, Edeson mentioned using a 50mm lens for The Big Trail; based on original Mitchell Camera purchase orders uncovered by Bennett, it’s also possible the cinematographer would have had 75mm, 105mm and 150mm lenses at his disposal.

For Edeson, nothing about shooting The Big Trail was going to be easy. Film running through Grandeur cameras, for example, had a tendency to buckle and curl, not only ruining the film but also burning out camera motors — a tough problem to overcome in remote locations. Several motors would be burned out in just the first week of shooting in Arizona.

Yet the most onerous aspect of shooting with the Grandeur — especially for personnel trained during the silent era — was having the cameras controlled by a sound truck, so that audio and picture could be properly synchronized. For camera veterans like Edeson, it was a case of the cart pulling the horse — sometimes almost literally.

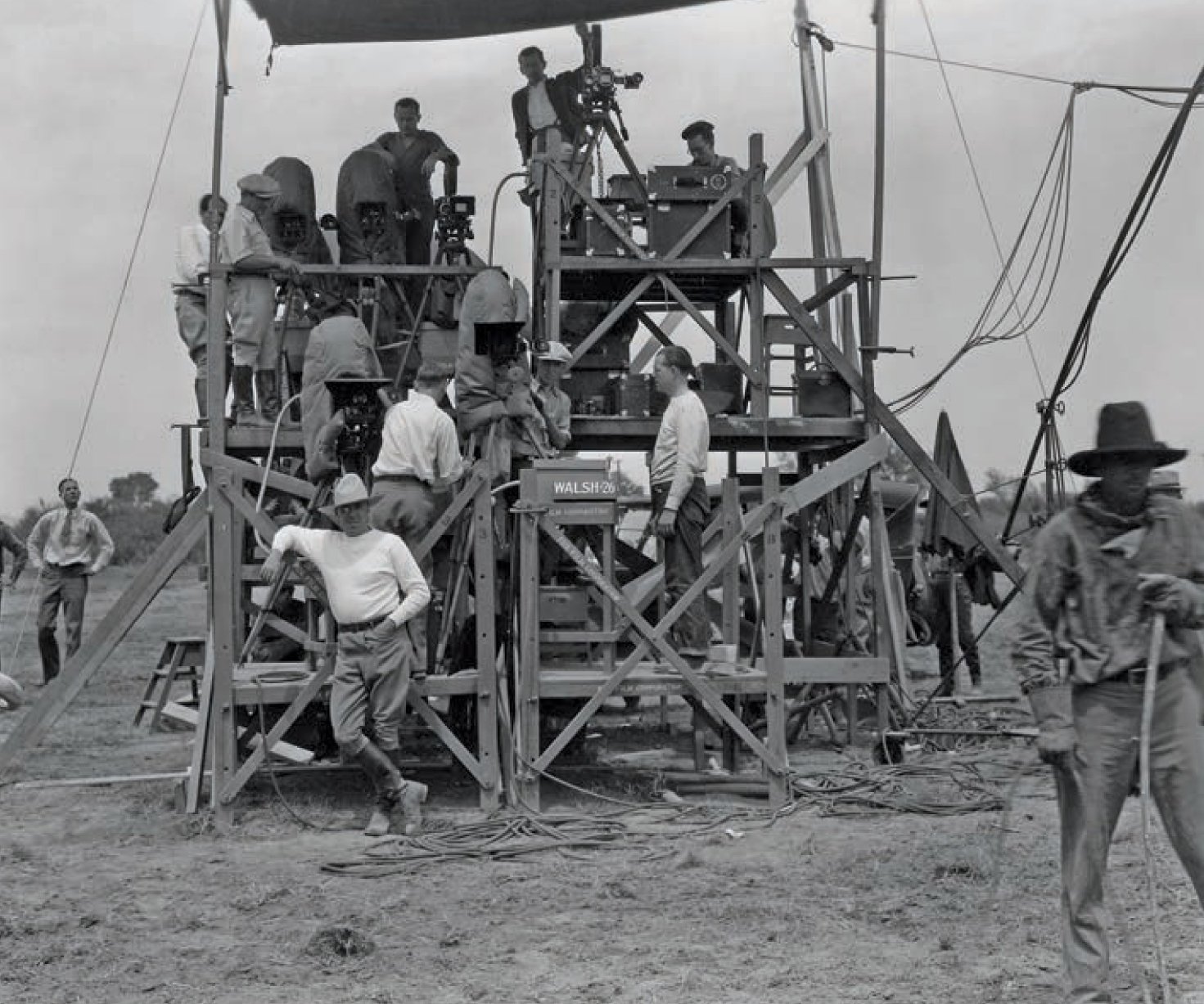

In the film’s colorful production log, “The Log of The Big Trail,” Hal Evarts describes tracking shots with 50 crewmembers hauling a dozen cables stretched from a sound truck to a two-tiered camera sled — supporting three 70mm Grandeur cameras and three conventional 35mm cameras — being pulled by 20 mules. If the mules got out of line, the shot would be thrown out of focus. “Not so simple,” as Evarts drily puts it, “this taking of a talking picture in the open.”

Further complicating matters was that each take had to be perfect, both for picture and for sound, because audio dubbing technology was still in its infancy. “They had to have incredible discipline on the set to avoid costly mistakes in sound,” notes legendary sound designer Ben Burtt. “Actors had to know their lines; you couldn’t drop something off-camera without ruining the take. It must have been an amazing process.”

The primitive state of post-production audio also dictated that Edeson would be photographing five different casts, one each for the English, Spanish, Italian, French and German-language versions of the film. What’s more, the film would be simultaneously shot in Grandeur 70mm by Edeson and in 35mm by Lucien Andriot, ASC.

Edeson also felt that the Grandeur images were too large to support conventional close-ups, so the production would mostly do without them. At the same time, the background detail visible to the Grandeur lenses was so extreme that Walsh and his team would have to invest enormous time (and money) populating backgrounds with thousands of extras, cattle, horses, wagons and buffaloes. And if a wandering sightseer a mile in the background happened to pass into frame and ruin a shot (as occasionally happened), everything would have to be set up again.

“The idea that widescreen made it necessary to stage even more action — background action as well as foreground action for the camera — is amazing,” says film critic Leonard Maltin. “What knocks me out is just the enormity of the production, and the vast amount of detail that it captures.”

Even with a $2 million budget, a crew of 200 (including 22 in the camera department), and an ex-cowboy director who’d once driven cattle from Veracruz to Texas, The Big Trail was looking like a big risk. Of course, it was the kind of risk Raoul Walsh was used to taking. After all, he’d just cast an unknown prop hand working on the Fox lot to star in the film.

Walsh was used to directing inexperienced actors. For his first film, the semi-documentary The Life of General Villa, he’d famously asked Pancho Villa to restage the Battle of Durango for the cameras. Savoring the publicity, the general gleefully obliged. By comparison, directing Marion “Duke” Morrison — an unknown 23-year-old fresh out of USC — would be easy.

Walsh was “dynamic, manly, forward-moving, bold, a craftsman,” John Wayne’s son Ethan Wayne recalls. At the John Wayne Enterprises archives, Ethan showed AC a carved bone knife given by Walsh to Wayne, commemorating The Big Trail's Wyoming shoot. Cradled in a bone sheath, the huge knife has an archaic quality that captures both the film and the primitive circumstances in which it was shot.

AC and John Wayne Enterprises also identified previously unseen footage from behind the scenes of The Big Trail, culled from a collection of Wayne’s home movies. The extraordinary footage features rare glimpses of wagons being lowered down a cliff, Raoul Walsh hard at work, and John Wayne and Ward Bond joking around in front of the Tetons. Wayne’s casual confidence, especially at age 23, is uncanny.

“John Wayne at that point in his life was simply a beautiful man,” says film critic and historian Richard Schickel. “Whatever awkwardness he had was covered over by his energy and general pleasure in his work. He obviously liked being an actor.”

“He was a born movie star,” adds Scott Eyman, author of the best-selling biography John Wayne: The Life and Legend. “He had that physique, he had that smile, he had charisma, he had presence. Your eye goes to him when he’s on camera.” Still, the young actor had to learn on the fly as the huge production kicked off in Yuma, Ariz. on April 21, 1930.

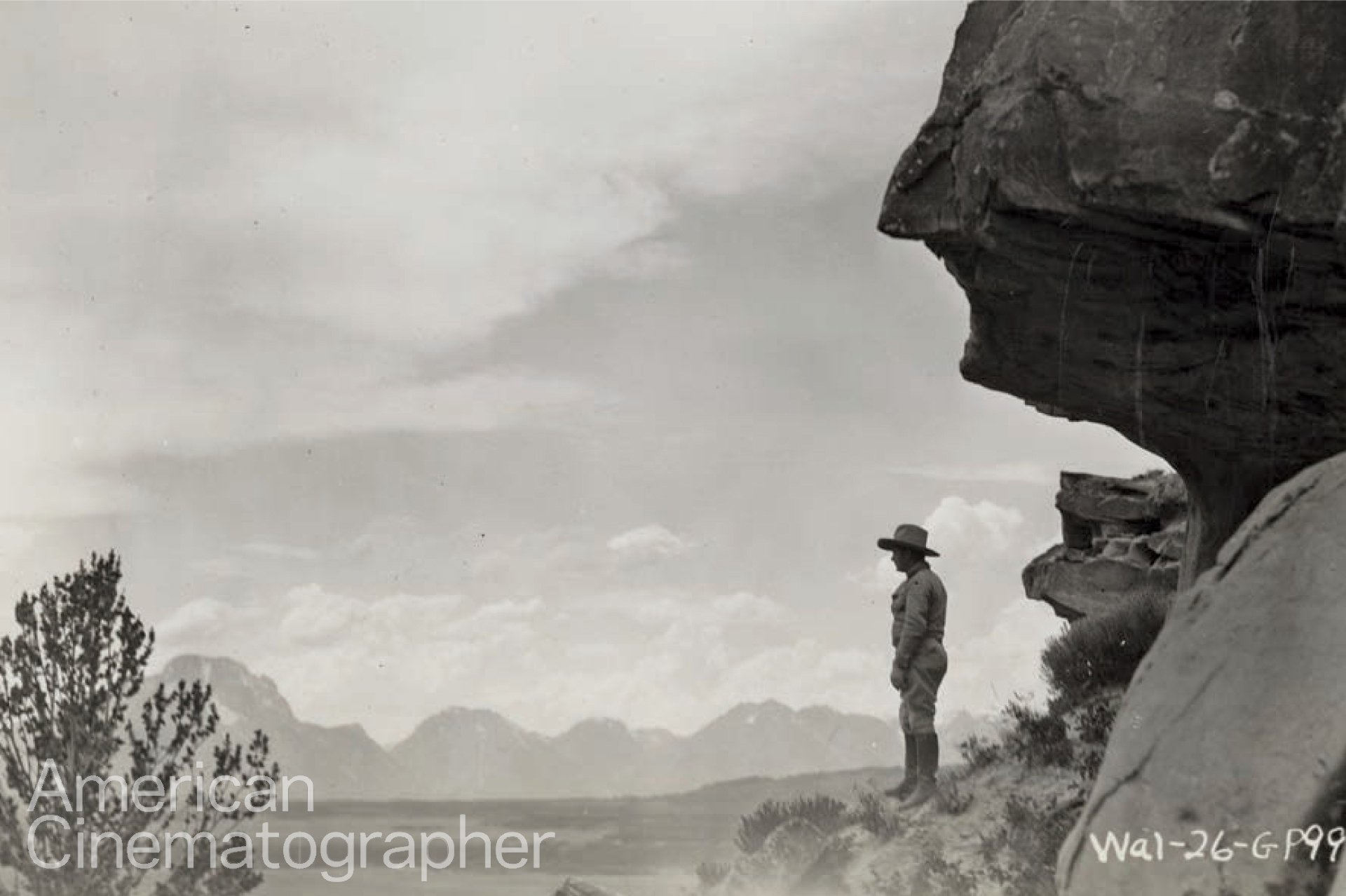

Immediately, Edeson began getting arresting images with his Grandeur camera — huge, detailed vistas of pioneers trekking off toward an infinite horizon. Documentary-like panoramas with breathtaking depth of field began pouring into the Fox labs. Like Ansel Adams with a large-format camera, Edeson and his Grandeur were capturing the sublime landscape of the still-pristine West. The Fox studio brass had never seen anything like it. In “The Log of The Big Trail,” Evarts writes that Fox officials “informed Walsh that the opening scenes were the greatest that had ever been received in Hollywood.”

Indeed, Grandeur’s depth of field in stopped-down, daylight situations was so great that Edeson began referring to the effect as “pseudostereoscopic.” At the same time, the cinematographer’s compositions never let foreground characters get swallowed up by nature’s spectacle. Taking full advantage of Walsh’s long takes, Edeson’s foreground figures ramble across the wide frame, casually asserting their dignity against nature’s indifference like migrant Dust Bowl families in Dorothea Lange’s photographs.

Most importantly, Edeson’s deep-focus compositions allow the audience’s eye to wander from foreground characters to background vistas. “The film is very modern-looking in terms of the use of widescreen,” says Hora. “They knew right away what they were doing in terms of how to use the frame, how to have people cross it instead of panning with them.

“There’s a kind of involvement you get, because you’re participating in the image,” Hora continues. “In terms of the screen and composition, it wasn’t equaled until CinemaScope came in and then Todd-AO.” Eyman agrees: “Photographically, it’s a masterpiece.”

Walsh felt so confident about his material that he improvised one of the most epic sequences of 1930s cinema: Using primitive log booms and pulleys, he lowered his wagons, pioneers and livestock over the side of a 350' cliff at Spread Creek, Wyo. This “lowering of the wagons” would become the signature sequence of the film, Walsh’s Fitzcarraldo-like flourish, and a prime spectacle for the Grandeur cameras. “The lowering of the wagons over those cliffs is just stupefying,” enthuses Maltin.

The production was also, presumably, recording better motion picture sound than ever before thanks in part to Grandeur’s oversize optical track. As Robert Gitt, founder of UCLA’s film-preservation program, explains, “The 70mm Grandeur format’s extra-wide variable-density track had the potential to provide greater audio fidelity with a significantly improved signal-to-noise ratio.”

Whether Grandeur achieved this higher fidelity is difficult to judge today, because surviving prints borrow heavily from the film’s narrower 35mm soundtrack. Still, Burtt feels the filmmakers achieved extraordinary results. “It’s an amazing film for sound,” he says, “in the sense that I look at it and I say, ‘How the heck did they edit and re-record this in 1930?’ The dialogue editing is pretty good. They had good microphone coverage. There are a lot of scenes with foreground dialogue and background action — with wagons, or people, or crowds — that are balanced very nicely.” Maltin agrees, noting, “The sound is as naturalistic as the imagery. It’s hard to believe this was made so early in the talking era.”

The shoot took its toll, however, as the production rumbled on over 4,000 miles in seven states. Dragging his team across burning deserts in Arizona, over snowdrifts in Jackson Hole, or through the tall timber of Sequoia National Park, Walsh pushed his cast and crew to the limit. The Big Trail required its onscreen pioneers to struggle through rainstorms, hunt buffalo, ford the Snake River in Wyoming, and fight off a band of 725 horse-mounted Native Americans (made up of Cheyennes, Crows, Shoshones, Blackfeet and Arapahos — not all of whom got along). Most of this was being done under conditions similar to those encountered by the original pioneers.

According to Evarts’ log, “Wagons were overturned, extra women were spilled from wagon seats or saddles into waist-deep mud, drenched to the skin, in danger from lurching wagons and trampling stock.” There were scores of accidents and broken bones. Walsh’s roughneck crew — which included ex-Texas Rangers, Chicago gunmen, Swedish sailors and ex-Marines — also took to brawling.

Another source of friction was drinking, with the cast getting hooked on Prohibition-era moonshine called “moose milk.” Walsh blamed the drinking binge on the film’s New York-based cast, whom he took to calling “the Booze Trust.”

“The name of the picture should have become The Big Drunk,” Walsh would later crack in his autobiography, Each Man in His Time. “The cast probably scattered more empty whiskey bottles over the Western plains than all the pioneers.”

At night, animals ran rampant through the camp. Pack rats ran off with actor Bill Mack’s toupee, actress Marguerite Churchill’s earrings, and actor Tully Marshall’s false teeth. One crewmember awoke with a bear cub on his chest, cozily cuddled up to his beard; a cook quit after a moose stuck its head into the mess tent, while another moose kicked actor El Brendel in the groin.

In the midst of the chaos, Walsh remained a tower of strength, impressing both cast and crew with his leadership. “He was a gallant man,” relates Schickel, who knew Walsh in his later years. “He had the right stuff.” Finally, after shooting what Walsh estimated to be 500,000' of 70mm film and 700,000' of 35mm film on a movie boasting 93 feature players, 1,800 head of cattle, 1,400 horses and 500 buffalo — with 700 assorted dogs, pigs and chickens — production wrapped on August 20, 1930.

There was only one problem: Hardly anyone was destined to see the 70mm epic Walsh had just made. Upon The Big Trail’s release, only two theaters in the country — Grauman’s Chinese in Hollywood, and the Roxy in New York — had been refitted with a 70mm Grandeur projection system. With most theaters having just undergone costly upgrades for sound, there was simply no Depression-era money left to refit for 70mm. So everyone else was going to see (and hear) The Big Trail on 35mm in the conventional 1.33:1 aspect ratio. What they saw and heard was a decent Western, but nothing spectacular. Without Grandeur, The Big Trail failed to live up to its name.

“It’s so spectacular in widescreen that if enough people had actually been able to see it the way it was intended to be seen, it could have been a different story,” says USC professor Rick Jewell. Instead, the 70mm Big Trail would not be seen widely until it was restored — by preservationist Peter Williamson at the Museum of Modern art, in collaboration with Ralph Sargent and others — in the early 1980s.

Although the 35mm Big Trail grossed $945,000 domestically, with $242,000 in foreign receipts, it wasn’t nearly enough to recoup the movie’s budget, which had ballooned to $2.5 million. Already overextended financially, Fox Film would go into receivership shortly after The Big Trail’s release, eventually merging with Darryl Zanuck’s Twentieth Century Pictures to create today’s 20th Century Fox. John Wayne would temporarily be banished to the purgatory of serials, with the Western genre soon to follow. And widescreen cinematography — viewed as costly and impractical — would be put back on the shelf until the early 1950s.

Still, everything new about The Big Trail — including its 70mm imagery, higher-fidelity sound, and John Wayne — would prove its appeal in years ahead. The legacy of The Big Trail would ultimately be as big as the frontier it depicted. As Hora puts it, “The Big Trail is monumental.”

If you enjoy archival and retrospective articles on classic and influential films, you'll find more AC historical coverage here.