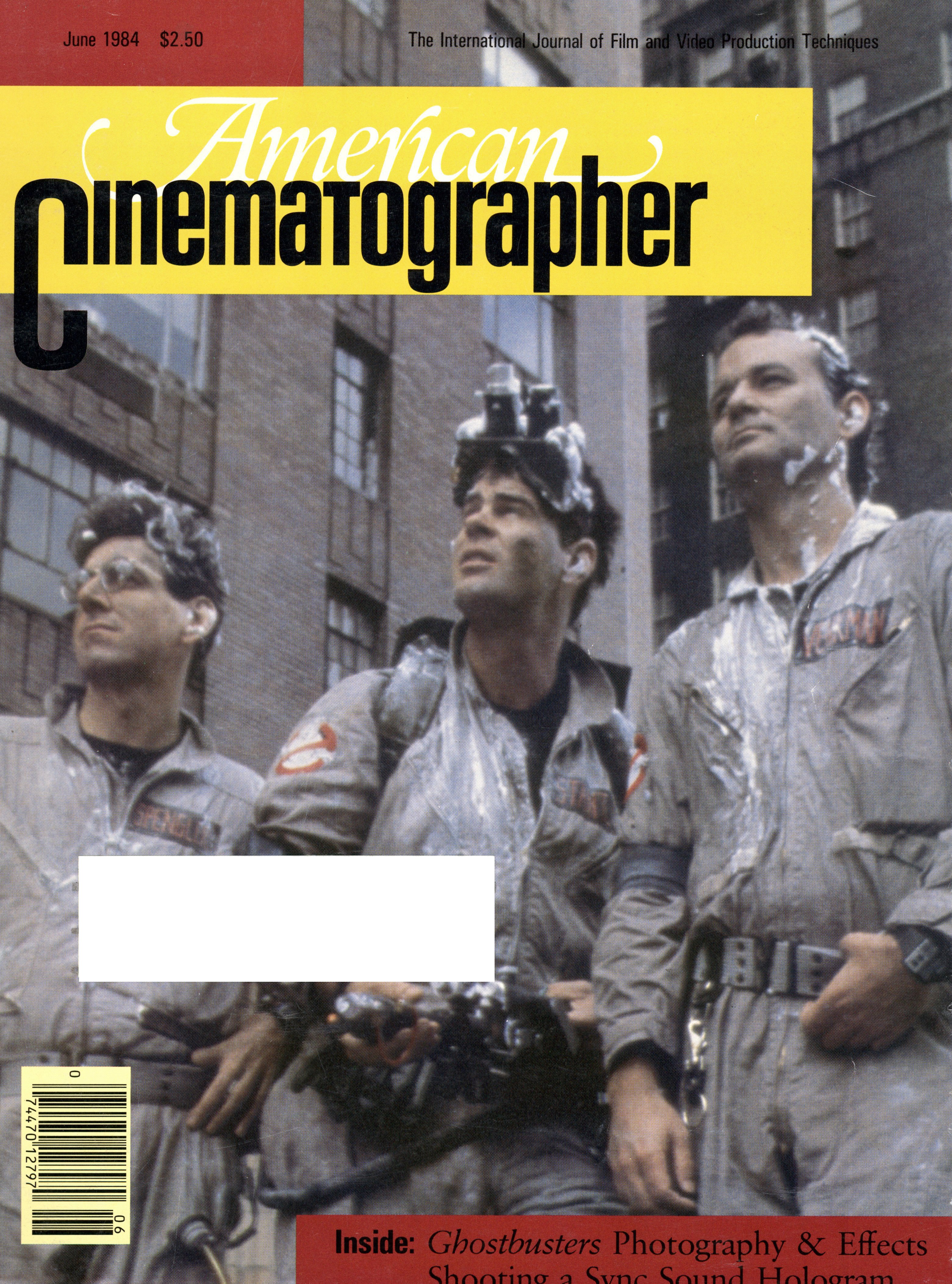

Visual Effects for Ghostbusters

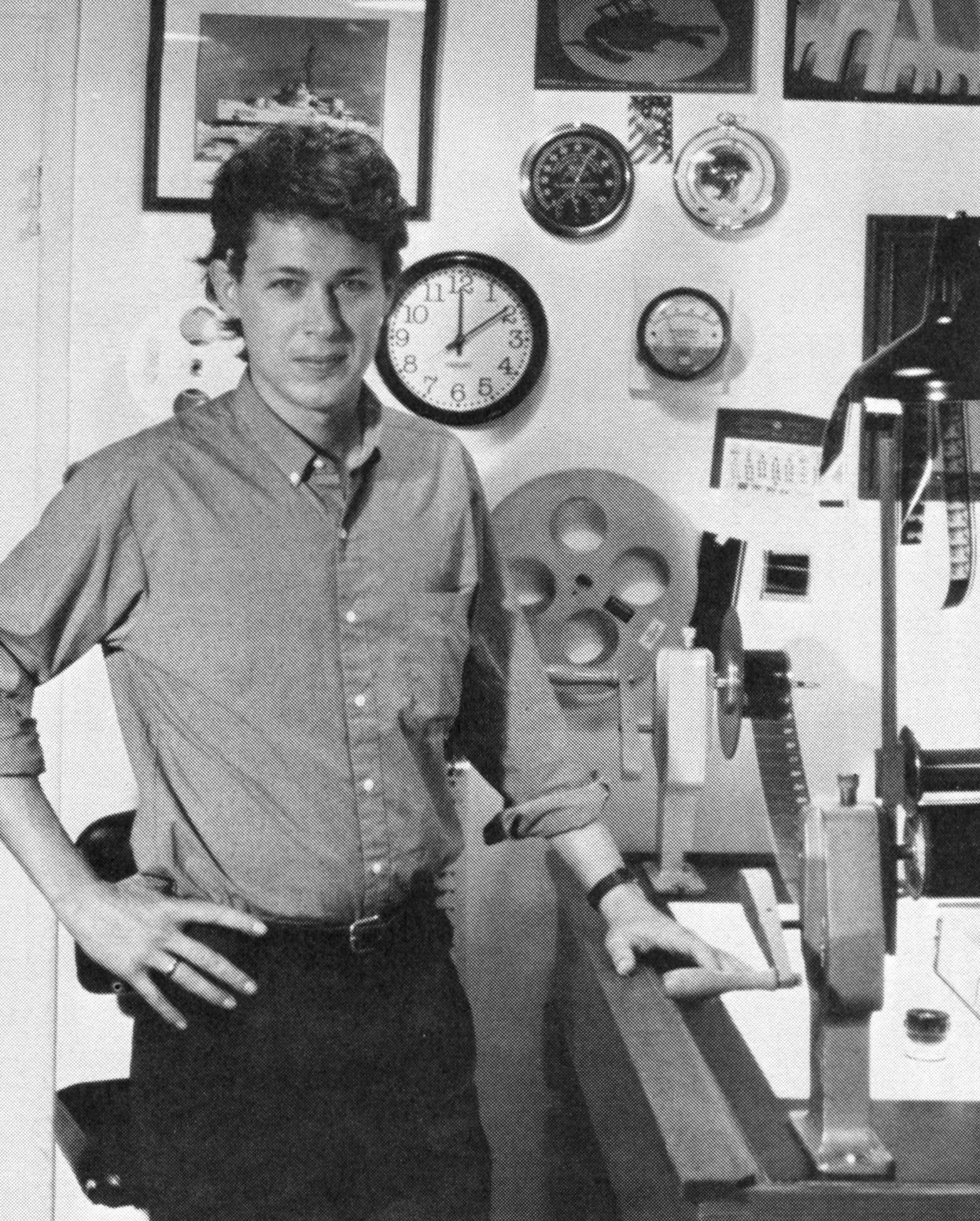

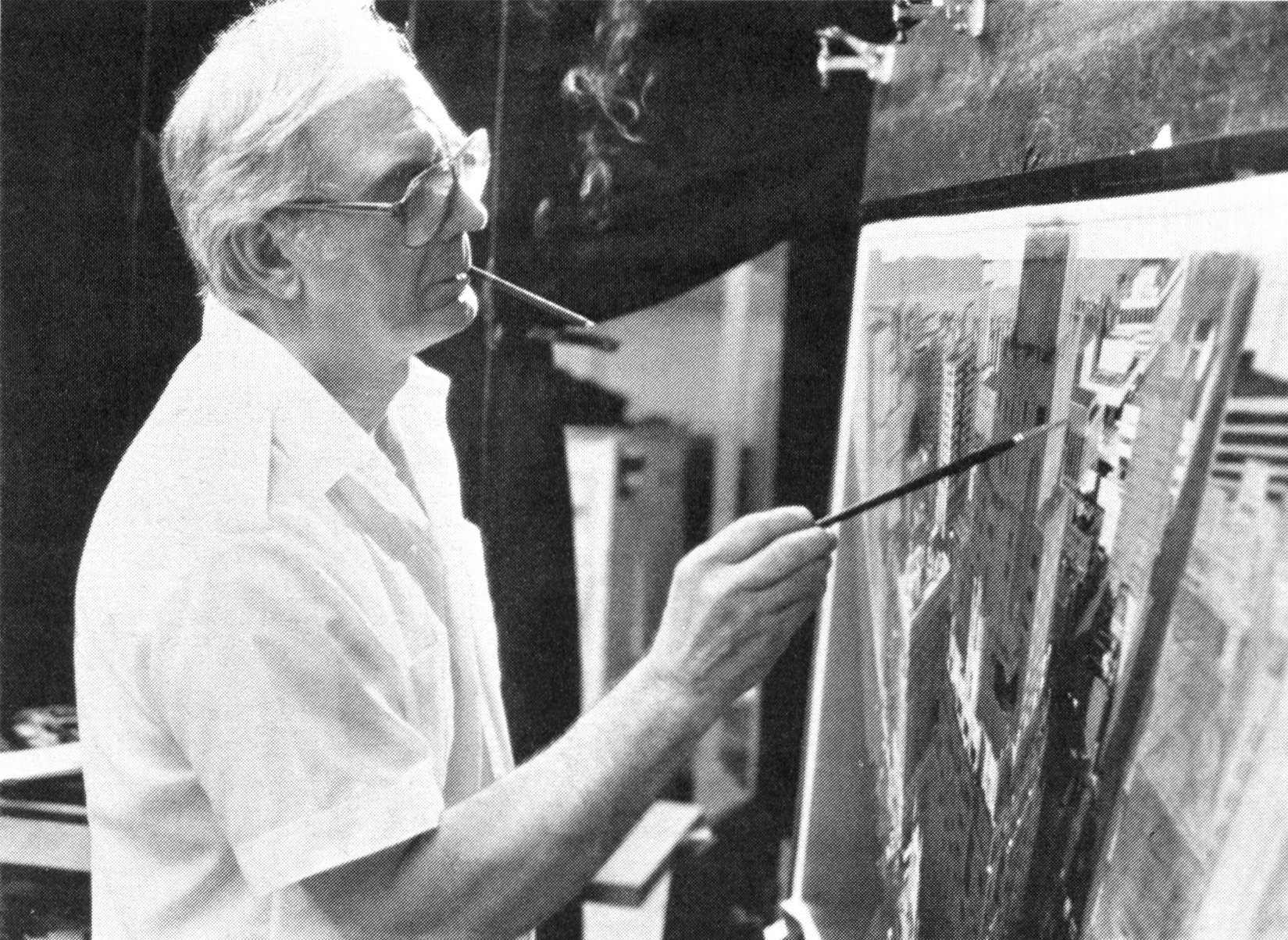

VFX supervisor Richard Edlund, ASC and his team talk about how they created a 120'-tall Marshmallow Man, changed NYC’s skyline and just what was in Dana Barrett’s fridge.

By Randy Lofficier

While Richard Edlund, ASC was still working on Return of the Jedi, he participated in a special effects seminar sponsored by Women In Film in Los Angeles. On the panel with him was Douglas Trumbull, and in the course of their conversation, Trumbull asked Edlund if he would be interested in joining Richard Yuricich, ASC and himself as a partner in their company Entertainment Effects Group (EEG). Trumbull was interested in getting out of effects work to concentrate on directing and developing his Showscan process. Yuricich likewise wanted to be freer to work as a director of photography.

Edlund had known Trumbull for many years, and they had talked before about working together, but the occasion had not arisen. Edlund was one of the first people involved in the special effects work on Star Wars and the development of the Industrial Light and Magic effects facility. He had, as he puts it, “been on a roll” for several years, garnering a handful of Oscars, nominations, and Scientific and Technical awards for his work on Star Wars, The Empire Strikes Back, Raiders of the Lost Ark and Poltergeist. He felt very lucky and was glad to be able to see the Star Wars trilogy through to its culmination in Return of the Jedi, but he was anxious to return to Los Angeles after living and working for so many years in Marin County. “I’m an Angeleno,” he comments. “By the time I started working on Jedi, I had spent a great deal of time under the Lucasfilm umbrella, and I wanted to go out and get wet myself. I felt that once I had finished Jedi, my job was essentially done.”

Edlund made a deal with Trumbull and Yuricich whereby he became a partner in EEG and the exclusive visual effects director for the company. Another instrument, Boss Film Corporation (BFC), was formed to facilitate working relationships with studios, and almost immediately two major projects surfaced within a week of each other. They were 2010 (the sequel to 2001: A Space Odyssey) and Ghostbusters, and it wasn’t long before there were as many as 163 people working at EEG/BFC on both these pictures. Many of the people came down from ILM to join Edlund in the new company and many of the others were people who had worked with EEG before. “It is,” he says, “an incredible talent pool, led by a group of 20 or so who function as a hunting band, a tight-knit group who are all going after the same goal and who constantly support each other.”

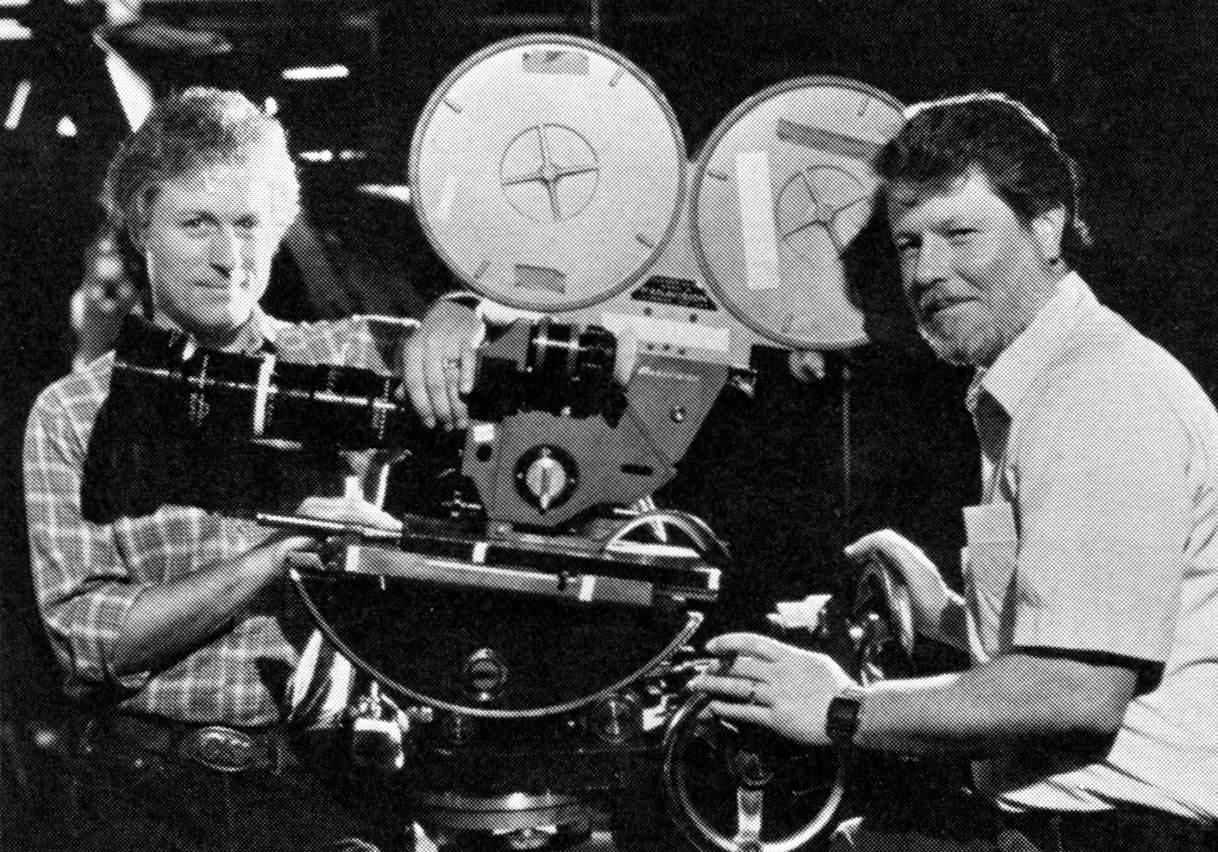

In addition to this talent pool, EEG has some of the most sophisticated visual-effects equipment in the industry. Everything is geared towards working in 65mm, a format that offers even more image area than VistaVision which Edlund and company resurrected for use at ILM. A 65mm frame is about a third larger than a VistaVision frame and, as a result, Edlund says that 35mm reduction dupe footage of effects can look even better than production 35mm footage. This creates the ideal situation for optical work in which diffusion can be used freely to balance elements being composited.

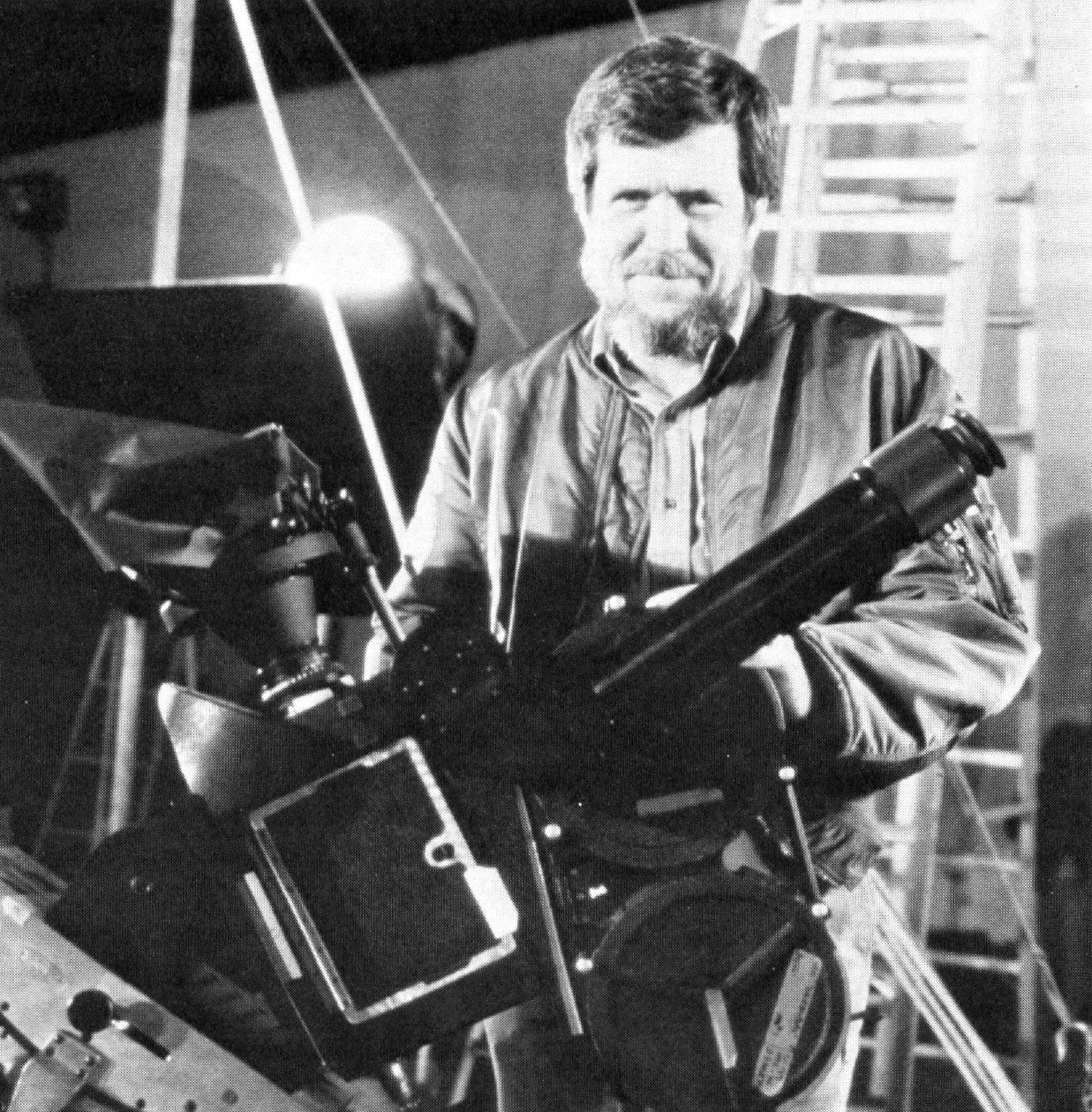

In addition to the 65mm equipment which was already at EEG, two unique additional pieces of equipment were built for the work on Ghostbusters and 2010. One is the world’s only 65mm high-speed, rotary-mirror reflex camera, which Mike Bolles and Gene Whiteman designed, and Gene built in about four months. Not only is it the only spinning-mirror reflex 65mm camera, but it can run at up to 105 fps. It could even conceivably run as fast as 120 fps.

The second new piece of equipment is a 65mm aerial-image optical printer which can composite 65mm elements and matte paintings directly onto 35mm or 65mm. It is built on a huge cast-iron base and has two Randle projectors, Grafton optics, an Acme camera, and electronics by Kris Brown and Jerry Jeffress. Edlund says it is the third printer he has built from scratch and he believes it is the best optical-composite printer in existence.

In addition, some of the other equipment at EEG was modified to suit their purposes and Edlund brought in his own 35mm optical printer as well. Among the more sophisticated accessories developed at EEG is a computerized exposure-control system for the matte camera, which greatly facilitates the shooting of wedge tests on all matte shots.

It was clear from its very inception that Ghostbusters would be a film that relied heavily on visual effects, although it was not possible to know exactly how much or what kind of effects work was required until EEG/BFC began working on storyboards for the script. What evolved was virtually a state-of-the-art textbook in effects work. Every conceivable technique with the exception of front projection was employed to create about 200 different shots for the film. Not only does the film involve fantastic creatures and outrageous weapons used to combat them, but a major story point centers on a non-existent building in New York City. As Edlund puts it, “The show was based on matte paintings.”

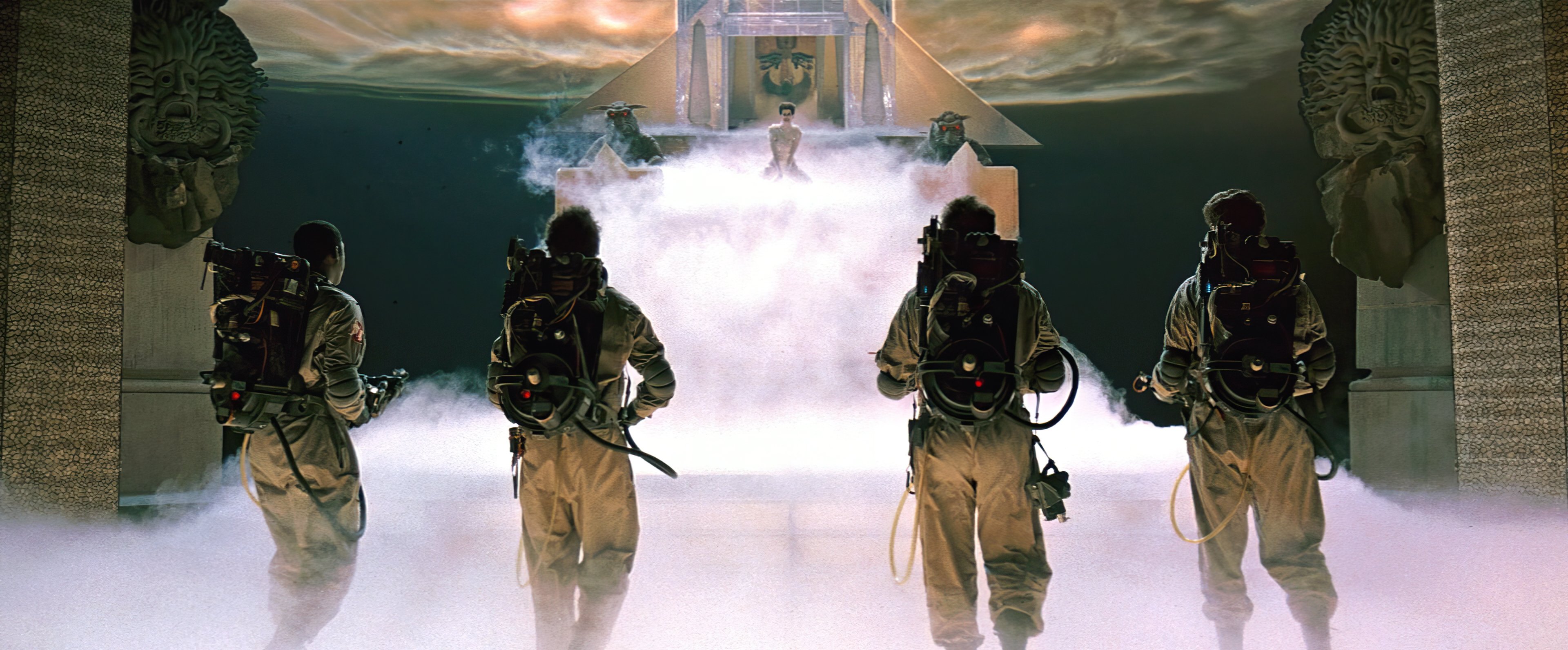

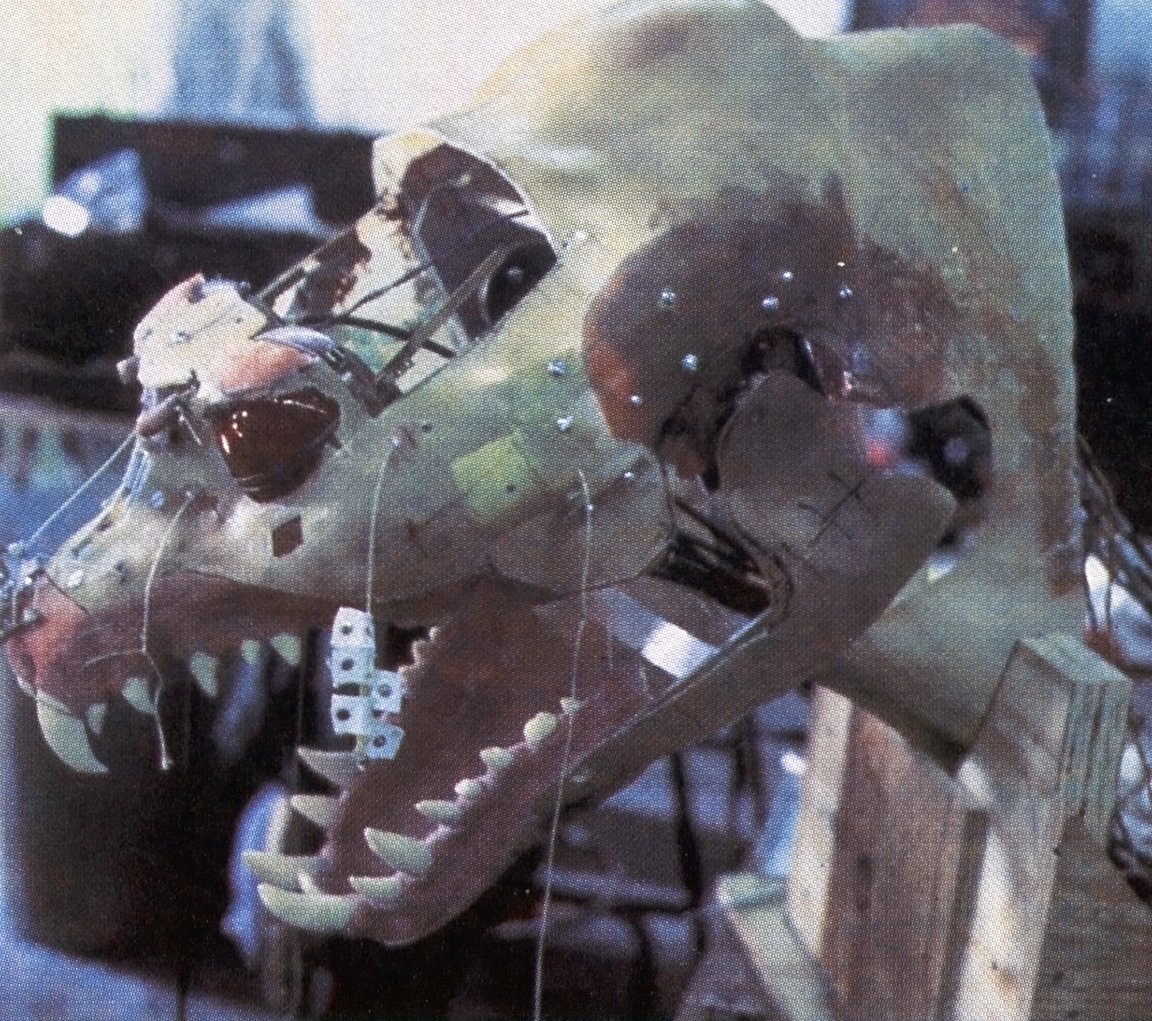

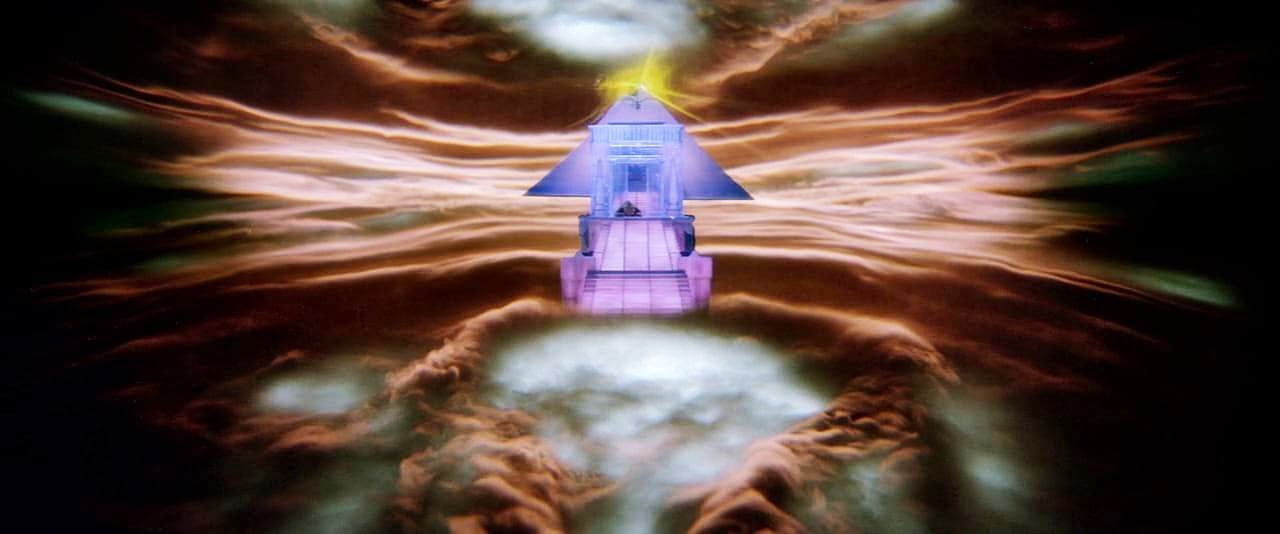

There are about 50 matte shots in the film with paintings by Matt Yuricich and camerawork supervised by Neil Krepela. Most of the mattes serve to alter the architecture of Manhattan to accommodate “Gozer’s Temple” and other imaginary locales, or to tie together footage of miniatures and live-action. Gozer’s Temple is supposed to be on top of a skyscraper in New York. Production designer John DeCuir built an enormous set at The Burbank Studios for the temple, but it was up to BFC to put the temple on top of a building in the Big Apple.

Yuricich comments: “To match with the temple top created by John DeCuir, I added about 30 stories onto the building that we actually used in New York. It’s actually an old-fashioned kind of matte work, because you must respect the realism and yet take license with it. In a way, this is harder because what you’re painting is really out there. For instance, there are many buildings two, three or four times taller than this one building. We cut those other buildings down shorter, so that the temple top looks like it’s up there alone. We want this to be the building you see. That in itself is difficult because the building looks different. Whenever you see the Empire State building in the New York skyline, you buy it, because you’re familiar with it. This building looks real, but people are going to wonder where it came from.”

Although the production schedule did not permit the kind of detailed production illustrations one might expect on a picture of this scope — in some cases, Yuricich had to do matte paintings with only a storyboard sketch as a guide — there obviously had to be a considerable amount of pre-production planning to permit this alteration of the New York skyline. Extensive location stills were shot and John Bruno, the visual effects art director, storyboarded all of the effects shots with an eye to how they could actually be accomplished. Conceptual storyboards had been done for a lot of the script before Bruno joined the production: “I re-boarded what had originally been done so that it would better fit our effects work.

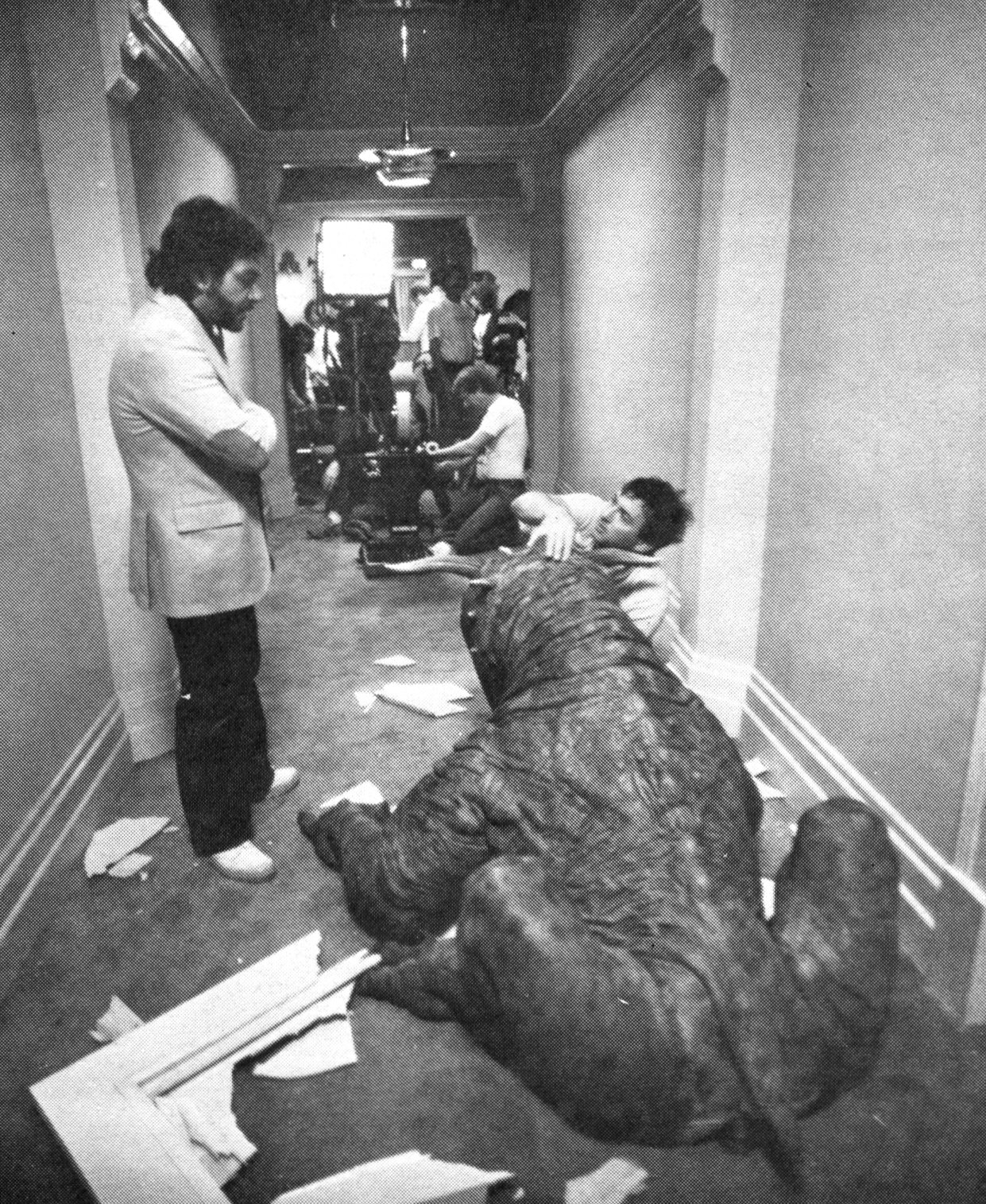

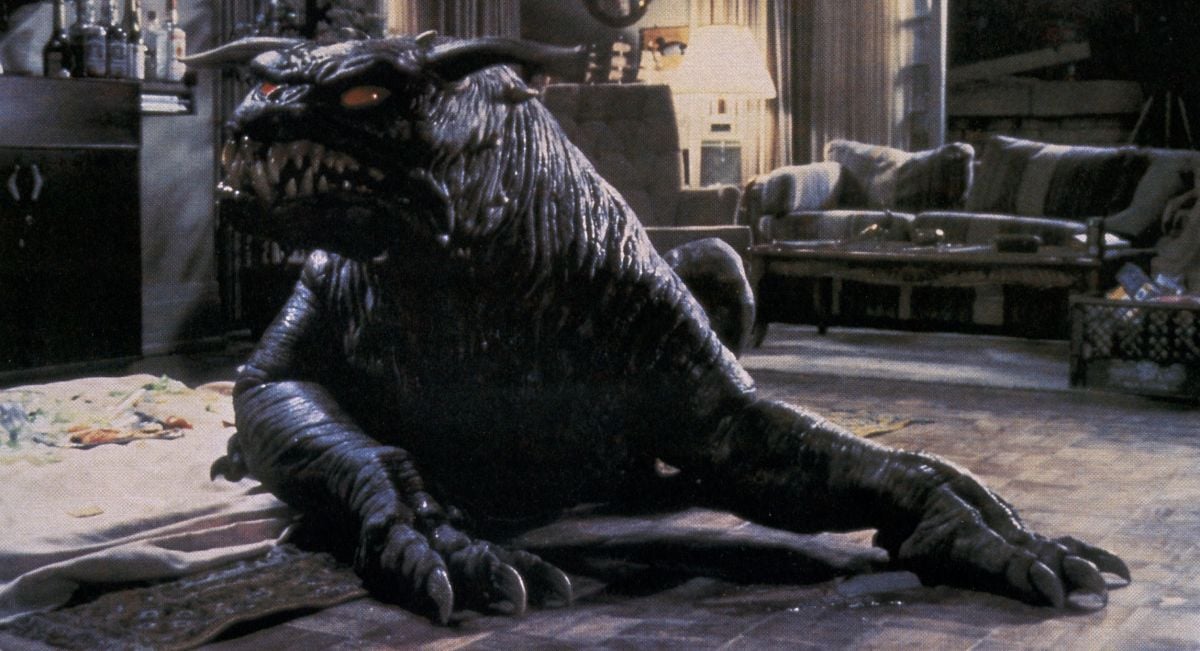

“After completing that, I set out boarding the rest of the film, starting with the Terror Dog in Louis’ apartment, the Onionhead sequence, and then the finale — the marshmallow man’s attack on 55 Central Park West. I came in with a more direct approach as to the effects. I would design a shot that I believed could be done. I approach boarding by trying to see the best way, the most spectacular way to produce a shot within the context of the story.”

Bruno would rough out the boards and show them to director Ivan Reitman for approval. Then they would be cleaned up by Brent Boates or Terry Windell and sent for final approval, where it would sometimes be decided if more or less action was needed, or if any other changes should be made. The final stage was to have a meeting of cameraman Bill Neil, Edlund, Windell and Garry Waller of the animation department, optical supervisor Mark Vargo, special projects supervisor Gary Platek, key effects foreman Thaine Morris, effects editor Conrad Buff, model shop supervisor Mark Stetson, ghost shop chief Stuart Ziff, and Krepela. They would look over the shots and decide what effects elements were necessary to bring the scene to life. Their decisions were then written into the notes of the storyboard.

“We knew early on,” adds Bruno, “that due to the incredible deadline we wouldn’t have much time for research and development, although there was some. If there had been six to eight months to finish, we could have experimented longer for optical to massage scenes to produce even better results. Our approach on effects was very direct. After some discussion, we chose the way to achieve the most believable result.”

Bruno sums up his philosophy, “Basically, effects are visual impression. You show the audience just enough of a given scene so they know what the scene is all about. You don’t want to hold on a scene long enough so that you can see that it is an effect. Star Wars is a whole series of two-second shots. Most good effects films are. We have been pushed to another maximum on Ghostbusters, in that some of our shots are fairly long. Wherever possible we tried to trim them down a little because there isn’t a shot in the world that you can get away with for 20 seconds.”

Any live production shot which was to be composited with another element was shot in 65mm using either the new high-speed reflex camera or a Mitchell 65mm BFC (blimped Fox Camera) which has been “hot-rodded” for effects work.

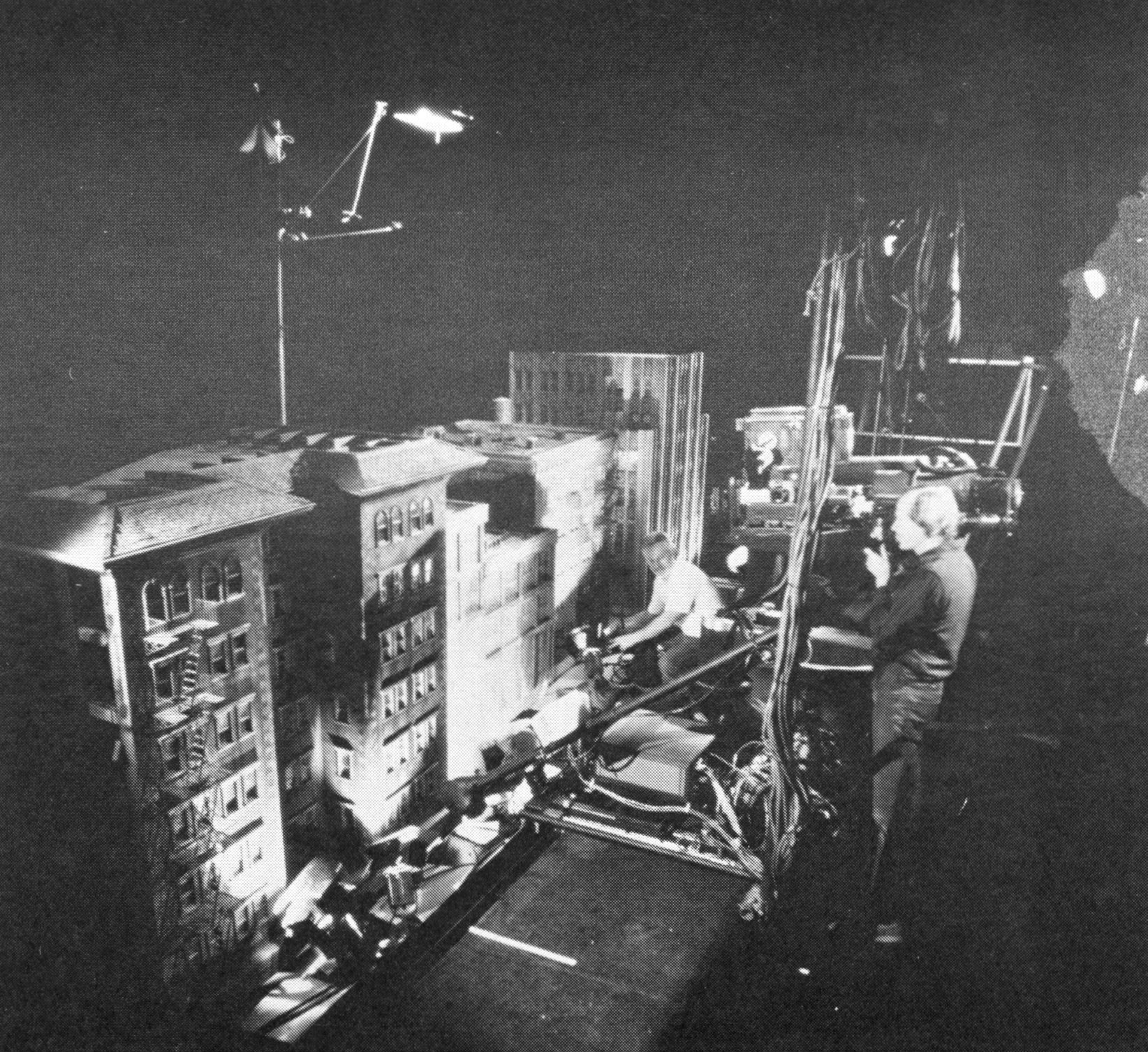

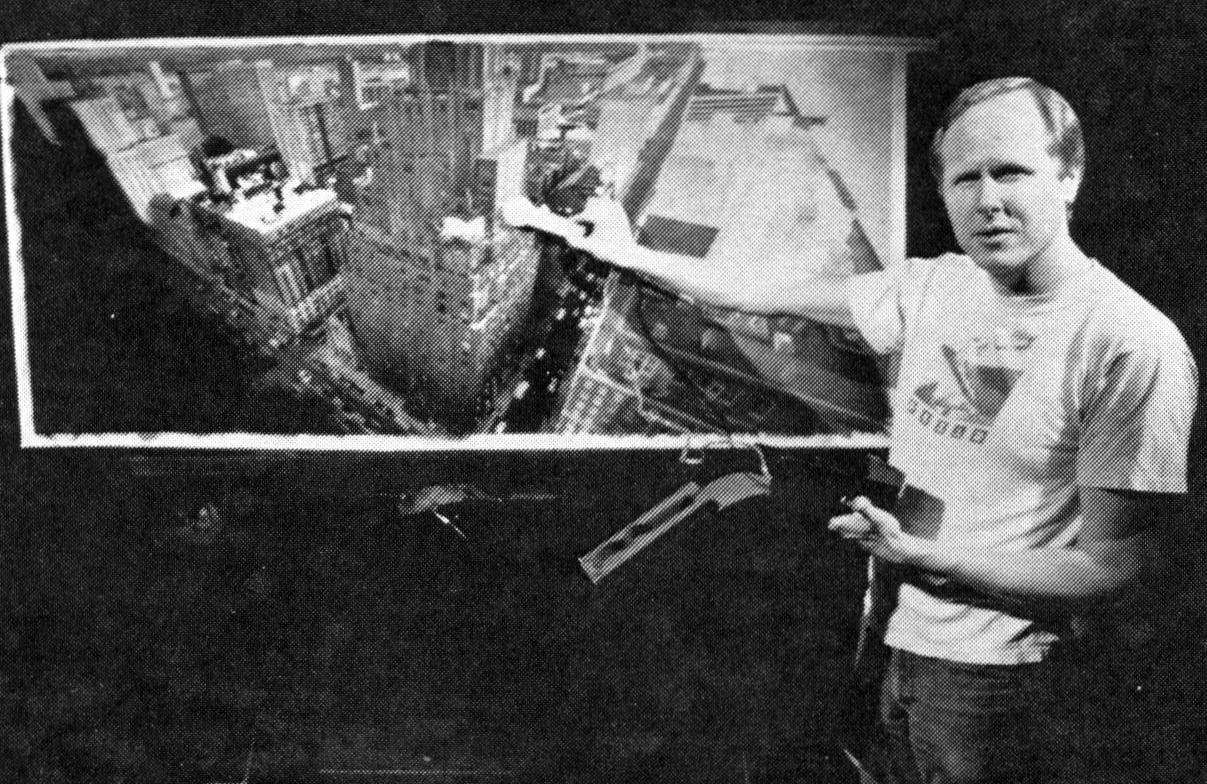

tracking shot of

miniature buildings

with the Compsy

motion-control

camera. The shot

will be composited

with three other

elements having a

matched move.

Krepela worked with director of photography Laszlo Kovacs, ASC to ensure that the 65mm footage would match that of the 35mm live-action photography. “We used the 65mm cameras to shoot simultaneously with the 35mm cameras,” he explains. “We would pick a different angle, or we would have a different shot than the first unit. We shot a lot of the temple sequence using the 65mm in a wide shot, with a bluescreen behind it, while the 35mm was getting the same action right next to us on a tight close-up on one of the characters. On many occasions, there were four cameras running, two 65mms and two 35mms. We did that because Ivan Reitman wanted to cover all the angles on scenes that were difficult to re-stage.

“We pretty much told Laszlo our needs for exposing our negative. We overexpose, as compared to what he’s doing with his negative. We rate our film a little different, more towards the normal of what Kodak specifies, to get a heavier negative. We find that, as we add effects, the heavier negative dupes better in the optical printer than the thinner negative that you can get away with in normal live-action production. Laszlo knew that, and he always had enough light for us.”

Krepela adds that depth of field was also a consideration in shooting the plates: “For matte painting and effects work in general, if you’re going to put something into the scene, such as a monster running towards you, you don’t want to have a short depth of field. If you did, it would be mushy back there, and then, when you start shooting your miniature, you’ve got to match that mush. It just adds a lot of complexity to the thing, and it doesn’t always look good, because what you want the public to look at will often be lost.”

Because the 65mm effects cameras were always used on set, there is very little chance that any effects would have to be matched to a 35mm live-action plate. Says Edlund, “The only time that really happens, is if there are one or two shots that are needed as an afterthought, and which we can do by running the elements in bi-pack in the composite camera. The other reason for that would be if we needed to shoot something at 350 frames per second with a special [35mm] camera that will go that fast. There’s no 65mm camera that can do that. Occasionally, we’ll shoot an element at 300 frames a second, then take the negative from that, blow it up to 65mm interpositive, and then it fits back into our process.”

Straight insert shots were also shot on 35mm. For example, a scene in which a lady ghost unzips Dan Aykroyd’s pants was originally intended to be a composite combining a live-action shot with an elaborate pair of self-unzipping pants but ended up being shot as a straight 35mm insert shot due to pressures of the schedule. There was also at least one instance where a 35mm test for an effect element turned out so well that it was used as an insert without any additional elements.

With a release date for Ghostbusters set for only 10 months after the initial go-ahead from Columbia, all of the effects work had to be done with a schedule that many would consider impossible. It did create some problems, but none that the crew at EEG/BFC were not able to overcome one way or another. The schedule did keep a lid on the natural tendency for a film like Ghostbusters to grow and become more elaborate once it goes into production. As the release date approached, it was necessary at one point to rethink the ending of the film and to return to some of the simpler ideas from an earlier concept. The team at EEG/BFC was also constantly on the lookout for ways to use existing elements or miniatures for additional shots. The initial glimpse of the other world through the refrigerator door, for example, was constructed entirely from elements created for other scenes. The miniature version of the building housing Gozer’s Temple built by Mark Stetson and his crew proved so convincing that it was used in a variety of ways that had not been originally planned.

One striking example of the matte work involved in Ghostbusters is also an excellent case study in rolling with the punches thrown by the release date. The script called for a long pull-back to the New York skyline after the explosion in Dana’s apartment. A set was constructed for the apartment so that the actors could be photographed through the hole in the side of the building and then a matte painting was to be used to permit the pull-back. The initial concept called for the final image to be a fisheye lens view of New York. Edlund took a still photo of the area of New York from a helicopter which was used for discussing the shot and Yuricich did a sketch of the fisheye perspective for the final composition which Reitman approved, but which Yuricich himself was not sold on. He did another sketch in which he matched the perspective of the still photo and everyone agreed that the less exaggerated perspective was more appropriate. Because of the deadlines, everyone was working against there were not full-color renderings of the scene done by a production illustrator to serve as a reference for everyone. Also because of the deadlines, Yuricich decided to use a color enlargement of the original photo as a basis for a portion of the matte painting. An enlargement was mounted on the board for the painting and served as a guide for about a quarter of the total painting. Even though it was necessary to paint over the photograph because of the difference in the way the camera sees the dyes in the print and the pigments in the paints, nonetheless the enlargement was helpful as a guide for the perspective and color scheme.

Unfortunately, there was some disagreement about which side of the building Dana’s apartment was located on, which resulted in the problem with the direction of the light in the scene. Yuricich was initially told to match the direction of the light in the still photo and the set on which the live-action was staged was lit to match the direction of the light in the photo as well.

Subsequently, it was concluded that the apartment had to be on the other side of the building with the result that the light needed to be coming from the opposite direc¬ tion. Yuricich had begun work on the painting using the enlargement and now found himself having to reverse the direction of the light as he painted over the photo. What had been the dark side of a build¬ ing now had to be the light side and vice versa. He also had to paint all the areas of the image that had originally been designed to be the exterior part of the set. All that was kept of the live-action was about a three-inch hole in the middle of the 7-foot painting. This posed potential problems for the camera move since there was obviously a limit as to how close to the painting the camera could start without revealing the texture of the painting.

Yuricich and Krepeia were able to make the shot convincing however and set about adding the kind of touches which function peripherally to help “sell” a shot. In order to justify the lack of traffic on the streets in front of the building, Yuricich added police barricades, but he felt it was necessary to add some kind of movement in other areas of the frame. Several members of the crew including Yuricich himself were photographed in the parking lot at an angle corresponding to the perspective on a balcony on a building in the scene. One member of the group got carried away with his big chance and the result was a degree of movement that Edlund described as looking like St. Vitus dance. There were usable pieces though and the footage was combined with the painting. Lights on the police cars were made to flash with another pass through the camera and movement was introduced in the crowds with a variation on the technique used to animate crowds in Ben-Hur. Instead of drilling holes in the actual painting, scratches were made in a black glass matte. A randomly colored board resembling a Jackson Pollack painting was placed behind the glass, lit so that bits of color showed through the scratches and moved back and forth. It was possible to composite all of these elements using separations of the live-action footage on the matte camera directly as well as sending separate elements to the optical printing department, and given the pressures on the optical printing department towards the end of the production, this seemed the preferable route.

Another way in which the pressures of the schedule plagued the matte department was that there was not time to tie down the color balance of some scenes before commitments had to be made either in lighting the set or in doing the paintings. Yuricich and Krepela had something of an uphill battle with the scene in which a vortex of boiling red and purple clouds is seen above the temple. There were problems matching the lighting on the set with the painting and the clouds shot in the cloud tank. Again Yuricich found himself painting over much of the set in order to blend the elements together.

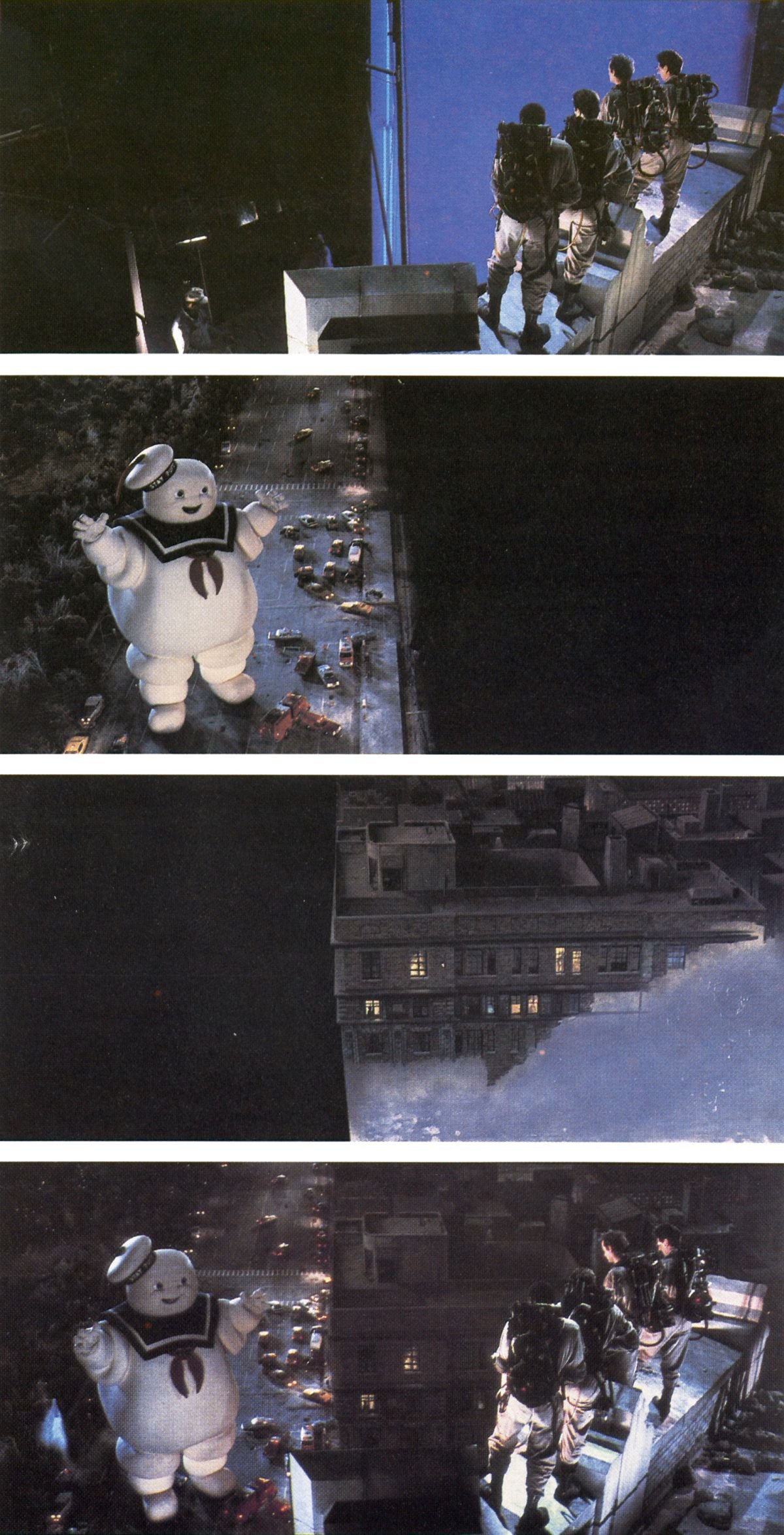

Not all of the matte work in the picture involved panoramic views of the New York skyline. Many of the paintings were isolated elements used to tie together background plates and bluescreen miniatures or to eliminate unwanted streetlights, etc. One example of this is a shot of the Stay Puft Man on the rampage, which is a tour de force in effects work.

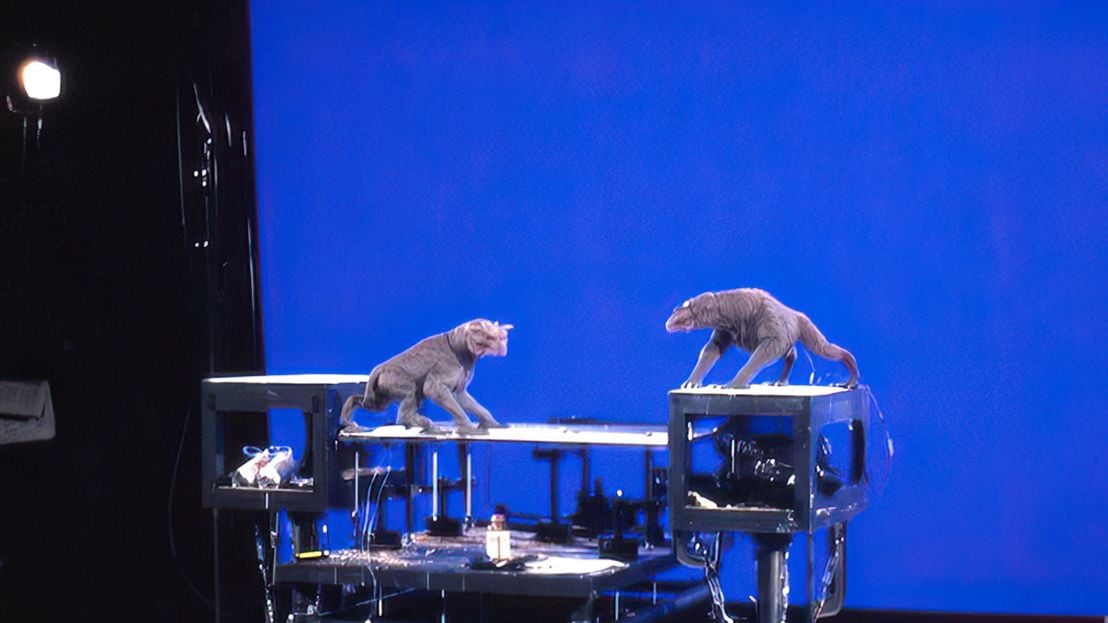

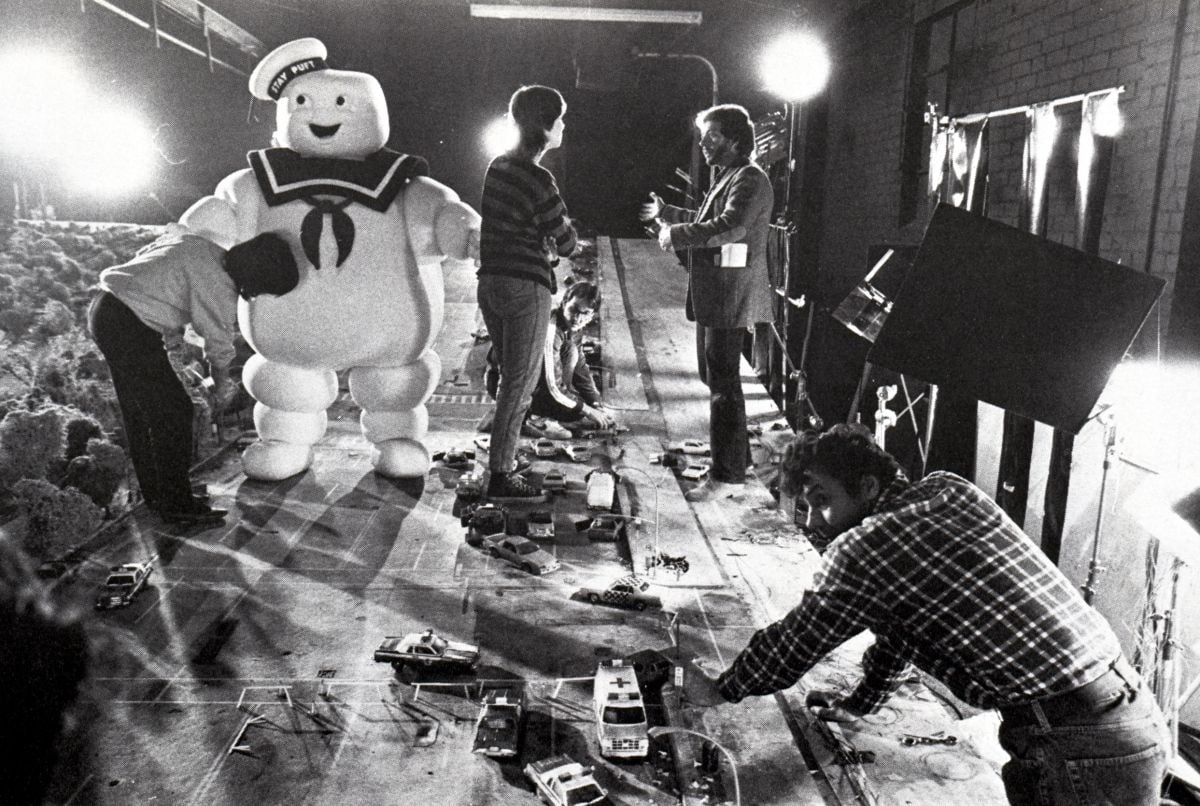

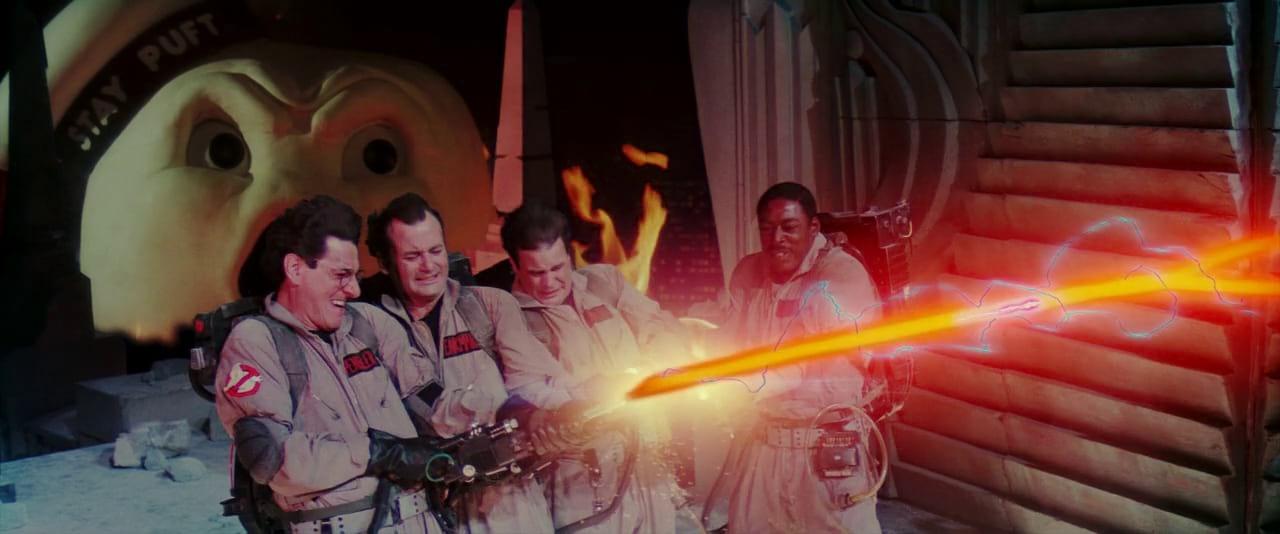

The Stay Puft Man is the giant marshmallow form used by Gozer in his final confrontation with the Ghostbusters. In one shot, we see our heroes on top of a building on the right side of the frame as the Stay Puft Man comes trudging down Broadway towards them. The actors were shot on a set against a blue screen and the Stay Puft Man is Bill Bryan in his costume walking through a miniature set. Tying the two together is a matte painting. The miniature set is a forced-perspective street with a park on one side and all manner of miniature remote-control cars, one of which crashes into a fire hydrant setting off a gusher of water. Along with Stetson, there were about 10 modelmakers working the set, each adding their own contribution to the overall effect.

Stay Puft Man was a costume built in Stuart Ziff’s ghost shop at EEG, which his creator describes as a combination sauna suit and universal gum (because of the way he was constantly fighting it). He was conceived as being 120' tall and filmed at 72 fps. Bill Bryan, who built the costume as well as acting the part, describes the problems he had developing his walk: “I spent some time just figuring out what the walk was going to be. Would it be a fat man waddling, leg and hand moving at the same time; or would it be more of a Godzilla swing? We ended up with the swing. Actually, it’s almost a regular walk with a little bit of extra up and down, but since we were shooting at 72 frames per second, I had to translate it into one-third speed movements. At first, I had a problem. I’d do it, see the test footage and remember the footage better than I would the actual movement. So the next test would be much too slow because I was moving as I had seen it. The net result was three times as slow as I intended it to be.”

Stay Puft Man’s body was made of foam sheet and the head, hands and feet were sculpted. Bryan did the hands and feet; Linda Frobos sculpted three heads: one happy, one frowning, and a third capable of both a grimace and a surprised look. There were front view suits, back view suits, side view suits, even a top view suit and a suit with extra-long arms and oversize hands for forced perspective. In addition to Bryan inside there were other operators contributing to his movements via cables.

The major problem with the Stay Puft Man costume was to enable it to burn, and at the same time make it safe for the stuntman that was wearing it. “Originally, I thought that we’d be faking the flame by airbrushing some browning and blackening while on camera,” continues Bryan, ‘‘and maybe some chemical mixture to get a little bubbling action and some bladders under the surface to get a larger bubbling action, and then animate in the flames, or stick them in optically. But, Richard didn’t want that, and the word came down that it did have to be fire, and it did have to look like he’d been doused with gasoline and lit.

“We were lucky in that the method that we had been using to construct the suit lent itself to including a layer of nonburning foam. And we were also lucky in that the type of foam that looked right also burned right! So, we started with one-inch foam. Then, we decided that, in order not to get as many pollutants in the air, a half-inch thick would be sufficient. Also, that way, it doesn’t eat as close to the stuntman. On the body, there’s a half-inch of flammable foam, then a half-inch of the best non-flammable foam which has 42 percent fire-retardant additives. We glued it down to a more rigid foam and then smeared another fire retardant into it. Now, it’s a leathery texture and has no air bubbles in it, which keeps the other foam from absorbing air.”

Another shot of the Stay Puft Man walking down Broadway towards Columbus Circle combined a bluescreen shot of the character walking on a ramp with a location shot of the real Broadway. In order to integrate the man into the scene, a considerable amount of frame-by-frame articulate rotoscoping work was required. As people running in the foreground passed in front of Stay Puft Man, each person had to be rotoscoped so that a matte could be created to keep them in front. In addition, a matte was drawn for a building in the background to enable Stay Puft Man to enter the scene by coming from behind the building. The camera angle permitted foreground objects to obscure the bottom of his feet, but it also resulted in a street lamp in the foreground which was distracting because it was right in front of the man. The street lamp was removed with the help of a matte painting for the central area of the frame.

The optical work required to composite all these elements was supervised by Mark Vargo, whom Edlund credits with shooting the most complex optical shot ever done (on Return of the Jedi) in one take. Vargo points out that all of the work done in special effects during the last decade has resulted in much more rigorous standards for optical compositing. “As we do more of these pictures,” he says, “our standards for evaluating the work and our eye for what makes a shot work or not work is becoming more and more sophisticated. In the past, if you had the color balance right and you didn’t have much of a matte line, then that shot would fly, but now there are all sorts of other considerations, like edge characteristics, contrast, and deliberate image degradation because of the superior optics in the printer.

These are subtle things; even though an audience can’t put a finger on them, they would sense that there was a problem with the shot if we didn’t deal with them.”

The shot of Stay Puft Man walking down Broadway is an excellent example of the kind of laborious attention to detail that went into the optical printing. The work began with the 65mm background plate photography on location in New York. The negative was shipped to MGM along with the 35mm negative for the principal photography for the scene. Best-light dailies were made at MGM and in the case of this shot, the 65mm plate was relatively bright and yellow, while the 35mm daily of the other scenes was darker and greener. Vargo evaluated the color in both prints and chose a compromise that he thought would work best. He was given a fair amount of latitude to do color correction for the picture, a responsibility which was somewhat simplified by the fact that there was no unusual theme to the color in the movie. The intention was simply to keep everything as realistic as possible.

A frame of the workprint was given to Bill Neil and his effects camera crew so that it could be put into the viewfinder when filming the bluescreen shot of Stay Puft Man walking along the ramp. The bluescreen shot was composed to put Stay Puft in the proper scale and position in the frame. He was filmed with no diffusion and there was no attempt to create matting in-camera with elements on the stage. Stay Puft simply walked the camera right and then turned to walk towards the camera at the place where he would appear to be coming out onto Broadway.

Bluescreen work is always shot without diffusion because it can affect the relative intensities of the bluescreen and the lighting on the foreground action, as well as make it more difficult to keep clean edges in the mattes.

As soon as Vargo had a color workprint for the bluescreen photography, he did a black-and-white test in the optical printer double exposing the Stay Puft Man onto the background plate to check the positioning of the man relative to the plate. This enabled him to pinpoint exactly from behind which building the man should emerge, and a registered color workprint of the plate was sent to the animation department supervised by Gary Waller and Terry Windell so that they could begin working on the mattes. The first matte was simply a hard edge for the building, which was shot on 65mm hi-con film and sent to the optical department as a separate element. Work was also begun on rotoscoping frame-by-frame mattes for all of the foreground action which needed to appear in front of Stay Puft Man.

Once he had tied down the color correction for the scene, Vargo made separations for the matte department from the negative for the background plate. The matte department needed separations rather than a color interpositive because the matte painting would be shot on Eastman Kodak 5247 color negative. By making black-and-white separations processed to a higher gamma it is possible to make a dupe negative on 5247 of the background plates for comparison to the test negatives that would be shot of the matte painting. Yuricich was given a clip of the timed print of the background plate as a reference and tests were shot as the painting was done. The final painting was shot on 65mm color negative along with a backlit matte pass as well and the negative was delivered to the optical department.

Vargo made 65mm color intermediates from the original negatives for the painting and the background plate. He made separations from the bluescreen photography and generated the mattes to drop out the blue. He combined the reverse matte of the bluescreen shot of Stay Puft Man with the rotoscoped matte for the foreground action to produce combined holdout mattes for the plate which held out everything in the plate which should be behind the Stay Puft Man.

He then began compositing the shot one step at a time, first wedging the painting together with the plate.

Sometimes it took two or three wedge tests to get the color balance of a painting to match the color balance of a plate. Once he was satisfied with the color match, he began wedging to test for the best diffusion to use with the painting. An additional adjustment in the exposure is required once the degree of diffusion is determined. Vargo has about five different types of diffusion materials that he works with and has yet to be able to shoot definitive tests with each one. Choosing diffusion materials is largely a matter of experience and judgment since there is no way to see the effect of the diffusion without shooting a wedge test.

After he was satisfied with the blending of the painting and the plate, Vargo began matting in Stay Puft Man. Again a series of wedge tests for color balance and diffusion were required, but in this case he was working from separations rather than an IP. The fact that Stay Puft Man was white made the shooting and processing of the separations especially critical since any imbalance would result in a tint to the white costume.

After all these wedge tests he was finally ready to composite the entire shot. The first time it was all put together, the background appeared to be moving relative to the painting. A steadiness test was immediately done on the original negative for the background plate and it was found to be rock-steady. What had happened, however, was that the IP had shrunk enough during the four months since it was originally made to cause registration problems. The IP had to be re-shot and re-wedged. All of the black-and-white elements were shot on Estar base, supplied by Kodak on special order, which prevents problems with shrinkage on the matte elements.

The second pass at compositing the shot had everything rock-steady but there was additional fine-tuning required in the color balance. On the third pass, the operator made an error and on the fourth pass a matte line showed up that had never been visible before. This was ironed out, but by the fifth pass, the mattes had gotten dirty. The holdout matte was re-made and on the sixth attempt, everything was fine except that someone finally noticed a little transparency around Stay Puft Man’s knee when he passed in front of a hot street light. Reshooting the matte to a higher density would have slightly altered the size of the matte and opened up a whole can of worms, so instead the existing matte was augmented with a small piece of .20ND filter which was positioned to hold back the light during the matte pass. This seventh attempt to composite the shot was completely successful and the negative was shipped.

Everyone knew at the outset that this shot would be one of the more complex effects shots in the picture, but Vargo says that some of the shots which initially he thought would be relatively routine actually ended up causing bigger headaches than the Stay Puft Man sequence. There were a series of shots involving the set for Gozer’s Temple where clouds had to be added to the background that Vargo describes as the most difficult thing he has ever done (and he has worked on Poltergeist, Dragonslayer, Flash Gordon, and Raiders of the Lost Ark as well as the Star Wars trilogy). The problem was that when the principal photography was done there had been no definitive decision about what should appear in the background representing the other dimension beyond the temple. The set simply had a black backing and there was even some rigging visible in front of the backing. To make matters even worse many of the shots involved smoke, so it was not possible to rotoscope a matte for the area into which the clouds needed to be matted. As Vargo puts it, “They didn’t know what they wanted, but they knew we could do it.”

While he professes to be flattered by such confidence in the abilities of the effects facility, he wishes his work had been made a bit easier by using a backing that was more conducive to generating mattes. As it was, he experimented with eight or so different techniques and found that he was able to pull a matte that could preserve the smoke in the foreground. Vargo regards the creation of mattes as the most challenging and creative aspect of optical work even though his efforts are rarely if ever appreciated by viewers who only see the final results. These particular scenes of the temple had a substantial amount of movement in the foreground and the foreground was also dark. He found that sometimes a half-stop difference in the exposure of the principal photography would make all the difference in the world when it came to pulling a good matte off the negative.

It is only possible here to hint at the scope of the effects work involved in Ghostbusters. There was stop-motion work involving sculpted creatures like the Terror Dogs, there were Gary Plater’s cloud tank and laser effects, there was elegant and elaborate animation involved in the creation of the Neutrona Wand weapons, and there were other full-size creatures such as Onionhead. It really would take a book to describe all the work done on the film. It would also have been an overwhelming assignment for even the most seasoned effects facility, and it was a veritable baptism of fire for the newly formed Boss Film Corporation.

Edlund, John Bruno, Mark Vargo and Chuck Gaspar shared an Academy Award nomination for Best Visual Effects for their expert work in the picture.

Edlund further discusses the film in this interview from the Friends of the ASC collection: