Walker, Luhrmann Band Together Again for Elvis

Frequent collaborators, cinematographer Mandy Walker, ASC, ACS and director Baz Luhrmann take the stage for this rock-star opus.

By Sarah Fensom

All images courtesy of Warner Bros. Pictures.

Director Baz Luhrmann describes his longtime creative partnership with cinematographer Mandy Walker, ASC, ACS in distinctly musical terms. “Mand and me, we are riffing,” says Luhrmann, referring to Walker by his nickname for her. “Our conversation always continues. When someone walks into a room and the conversation doesn’t naturally come to an end, that’s good enough for me.”

Walker recalls her initial connection with Luhrmann in much the same way: “When I first met Baz, we immediately started riffing — talking about references and taking photos.”

For nearly two decades, “riffing” is the process that’s bonded the filmmakers as they’ve tackled projects of every size — and what infused the spirit of their latest feature, the rock-and-roll biopic Elvis, which Luhrmann has called a “three-act pop-cultural opera.”

Beginnings

Walker and Luhrmann’s first meeting happened in 2004, when they discussed what would become their first joint collaboration: the Fellini-esque branded short Chanel No. 5: The Film, which stars Nicole Kidman and ranks among the most expensive commercials ever made. Luhrmann had already seen Walker’s work on commercials and on the film Lantana, the 2001 psychodrama from director Ray Lawrence (AC Feb. ’02), and although he describes that film as “the antithesis” of what he was doing at the time, he was impressed by the “feeling for camera and drama” that Walker possessed.

Next came Australia — their 2008 epic set against the backdrop of its titular country’s World War II-torn era, which also stars Kidman, alongside Hugh Jackman. For that feature, Walker and Luhrmann claim to have shot the most 35mm motion-picture negative on a single feature film in film history, and the director is currently re-cutting and augmenting the Australia footage into Faraway Downs, a limited series for Hulu.

Six years later, the duo reunited for a second commercial short, the opulent Chanel No. 5: The One That I Want. “Something that I had never encountered before, on any of the jobs I worked on, was how much research Baz had done for that first Chanel project,” Walker recalls.

She notes that Luhrmann is always remarkably clear about the story he wants to tell and the emotion he wants to create, and the two soon discovered that photography would form the core of their bond. “When we’re scouting or just walking around, we’re both carrying a Leica digital camera and we’re taking pictures non-stop — sometimes with the actual movie in mind, and sometimes just for texture.”

During these outings, it’s not uncommon for the pair to capture the same images — even if their subjects are seemingly mundane objects, like a wall or a slab of concrete. “I don’t know anyone else who does this,” the director says with a laugh.

Rocking Lenses, Rolling Cameras

Elvis depicts the evolving life and career of Elvis Presley (Austin Butler), framed by a selection of the rock-and-roll star’s iconic performances and narrated by his longtime manager, the controversial Colonel Tom Parker (Tom Hanks). The film blends Luhrmann’s visual maximalism with Walker’s energetic camerawork and beat-for-beat re-creations of vintage footage. Both filmmakers’ shared passion for stills is an essential ingredient of the movie’s style. For example, mid-century photographers Gordon Parks (whose work Walker reveres for its singularly desaturated “blackand-white color”) and Saul Leiter provided inspiration when the filmmakers were crafting shots that represent Elvis’ early years.

Lens selection for Elvis was informed by five years of deep research on these references and many more. After Walker and Luhrmann discussed their influences with Panavision’s Dan Sasaki, an ASC associate, he showed them various 65mm lenses, but they decided on the company’s Sphero 65s, which the filmmakers opted to employ for the first half of their film.

Walker and Luhrmann decided to change lenses as Elvis’ story evolves. Their use of a T Series anamorphic lens for the sequences set in the 1970s is one key example of this approach. “When Elvis goes to Vegas, we wanted to shoot anamorphic because that’s what represented the ’70s to us,” Walker says.

However, the cinematographer notes that these lenses needed some adjustments to capture the vintage feel they were after: “Modern anamorphic lenses are much cleaner and crisper, and the artifacts that they started with in the ’70s have been taken out, so we got Dan to put those back in,” she explains. “Once he did, the horizontal flares didn’t just have a blue, kind of Star Trek flare anymore — they had more colors, and the edges dropped off in a more organic way. All the lenses were tweaked at least twice to get the right look for our movie.”

The filmmakers also discovered an 85mm Petzval lens at Panavision that they used for dream sequences, flashbacks, drug experiences and shots of the Colonel on morphine that are used as a framing device in the film. “It creates a vortex, so your eye gets drawn to the center of the frame,” Walker says.

While at Panavision, the duo looked at both 35mm- and 65mm-format digital cameras, but decided on the latter. “We both said, ‘Well, this is an epic story — why not shoot on 65mm?,’” Walker recalls. The cinematographer chose Arri Rental’s Alexa 65, which she had previously used on Mulan and The Mountain Between Us. “That camera is great,” Walker says. “I compare what it can do to the look of Lawrence of Arabia, which has wide, beautiful vista landscapes but also a sense of intimacy.” She notes that the Alexa 65’s lower depth of field allows the camera to capture intimate shots and separate the character in close-up from the background.

Commanding Performances

Luhrmann’s research dictated the look of the film’s performances as well — sometimes to a tee. He dug up photographs by Alfred Wertheimer to serve as references for a 1956 charity concert headlined by Elvis and his band at Russwood Park stadium in Memphis, Tenn.; dove deeply into Elvis’ wildly successful 1968 “Comeback Special” to re-create its NBC broadcast (formally titled Singer Presents … Elvis, in recognition of the show’s sponsor, the Singer Corporation); and relied on Denis Sanders’ 1970 documentary, Elvis: That’s the Way It Is, as a guide when bringing Elvis’ first performance at Las Vegas’ International Hilton Hotel to life.

Walker’s job was to meticulously re-create these references, down to lenses, camera movements, lighting styles and cues — a process Luhrmann describes as “trainspotting.” The cinematographer says she was tasked with “replicating footage — concert footage of Elvis, mainly — that many people are familiar with.” Walker’s trainspotting also involved a great deal of testing, creating very specific LUTs, returning repeatedly with her Leica digital M-P 240 to the locations as they were built on the backlots and soundstages at Village Roadshow Studios in Queensland, and running through multiple dress rehearsals with their cine cameras on set. (“Just like the theater,” Luhrmann offers.)

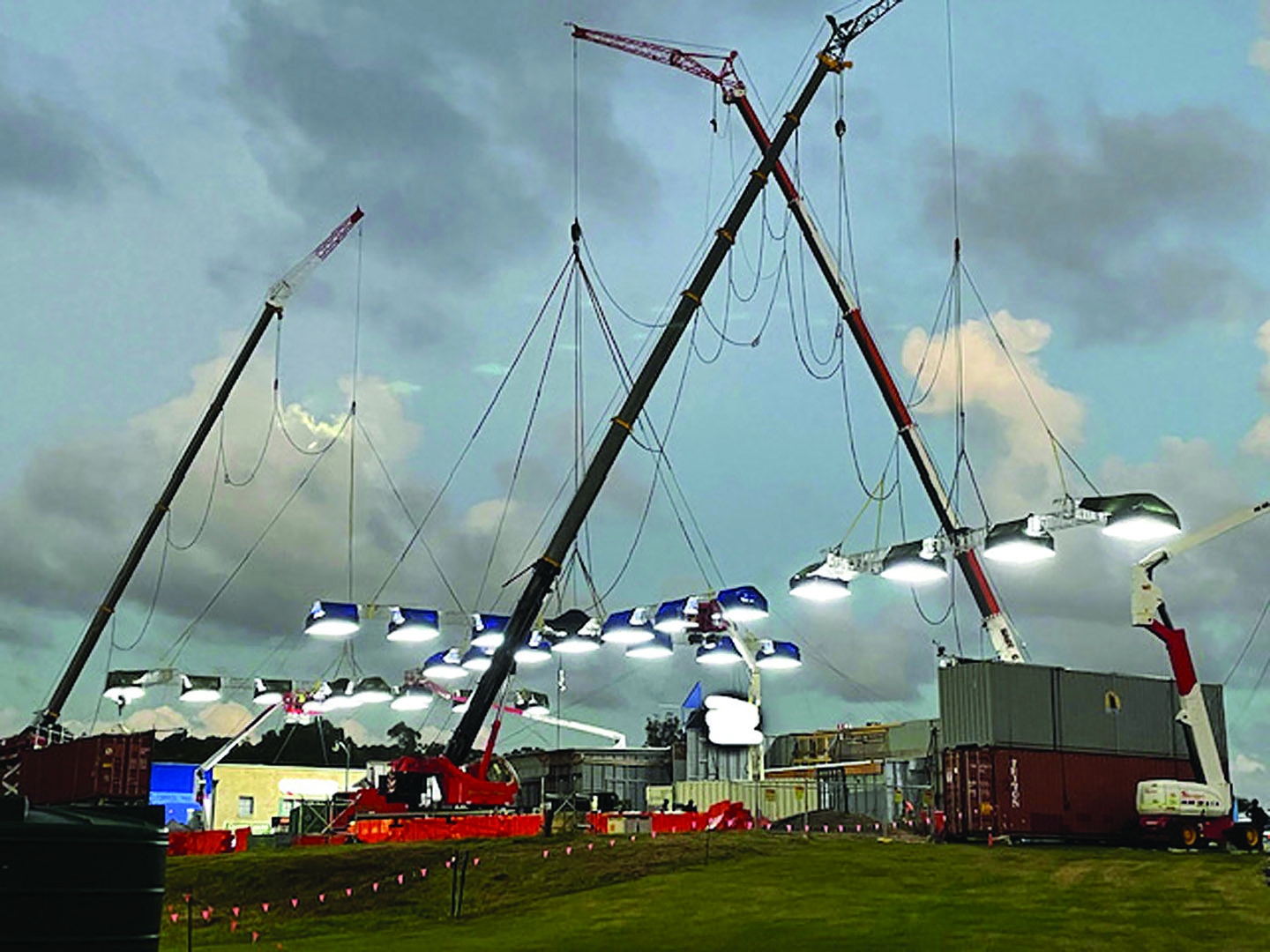

The setups the filmmakers re-created would often determine their lighting. Commenting on the Russwood performance, Luhrmann explains, “If you look at those [Wertheimer] pictures, what makes them so iconic is that all the heads in the audience are backlit.” The photographer was standing onstage behind Elvis, with the baseball stadium’s towering banks of metal halide lights illuminating the crowd from the back. “We knew the iconography was so embedded in a certain portion of the audience’s mind that we had to find a way to reproduce the feel of it,” Luhrmann says.

Walker notes that for the Russwood setup, “we used a series of Maxi-Brutes joined together to create the shape of the stadium lights — similar to those on the field — so they could be featured in the movie’s shots. At the front of the stage were period-accurate ground rows that the art department built, and we put LED fixtures inside, as they run cooler in temperature than the tungsten bulbs that traditionally would have been inside and don’t get hot. That made them safe for the extras playing enthusiastic fans who drape themselves over them to try to get close to Elvis.

Throughout the film, especially with the concert sequences, it was a dance between myself and the art department because we had to have vintage lighting fixtures in the shot.”

For the sequence depicting the ’68 Comeback Special, the ceiling of the television-studio set would be visible, so Walker again worked with the art department to have period fixtures made: “They found old period fixtures, which we repaired and used as practical lights, but some we changed the insides of again and fitted with LEDs to have a more complimentary, softer light on Elvis’ face.” For the International Hotel performances, the filmmakers brought in period PAR cans sourced from old rock-and-roll clubs. But in every instance, Walker added LEDs — Arri SkyPanel 360s, Mac Viper moving lights and Arri Orbiters “to compliment the many period lights in shot whenever possible.” She notes that “the film lights are more controllable — we could change the color on the dimmer board, and we could have them on our iPad setup with us on set and make slight color or brightness changes very quickly.”

Walker abided by her general rule to prelight the sets or locations for 360 degrees, and be prepared for shooting in any direction, or shots that panned around. “It doesn’t interfere with the actors’ space as much, and subsequently we are quicker at changing setups to have these lights in place, ready to be turned on or off. And I can physically drop them down from the grid, or change the angle for everything remotely from motors — and change the color or brightness on a dimmer board, rather than bringing new lights into the room.”

To avoid compromising Butler’s range of motion, Walker created an LED eyelight for the actor — on a boom pole operated by lighting best boy Matthew Linfoot — which she likened to an old-fashioned covered wagon. “I would have it so that if he moved around, the eyelight would move with him. But it wasn’t always fill lighting his face; sometimes it would be a reflection and give him just a glint in his eye.”

Abstract Riffing

Despite the filmmakers’ quest for accuracy, Elvis wasn’t pure reproduction. “Once we had our trainspotting in the can, we’d do what we call a riff,” Luhrmann says. “A riff was about saying, ‘We’re going to unleash ourselves from the constraints of period coverage — we’re just gonna be Elvis!’”

For Luhrmann, this “abstract riffing” was defined by both “the energy of Elvis and modern camera usage,” and afforded opportunities for him and Walker to deviate from the rest of the film’s mix of “absolute reproduction” and “good old-fashioned coverage for drama and story.”

Riffing also gave way to improvisation. This was especially true of one scene that shows Elvis practicing with his band before his Vegas debut. The sequence includes what looks like a continuous, 360-degree Steadicam shot with various lighting and costume changes. Says Luhrmann, “This was something we planned, plotted and rehearsed. And we did it all perfectly — except it wasn’t working.” Instead of shooting with the band’s instruments muted to playback, Luhrmann used the same camera setup, but had Butler improvise the scene with all of the musicians actually performing. The director notes that in this case, Walker’s planning enabled them to pivot seamlessly to a different performance style. “We were so ready that [Austin] was able to just go free. That’s really what all the preparation is about.”

Walker has earned ASC and Academy Award nominations, among other honors, for her outstanding cinematography in the film.

After the publication of this story in the Dec. 2022 issue of AC, Walker and Luhrmann discussed the project in an episode of ASC Clubhouse Conversations, interviewed by Greig Fraser, ASC, ACS.