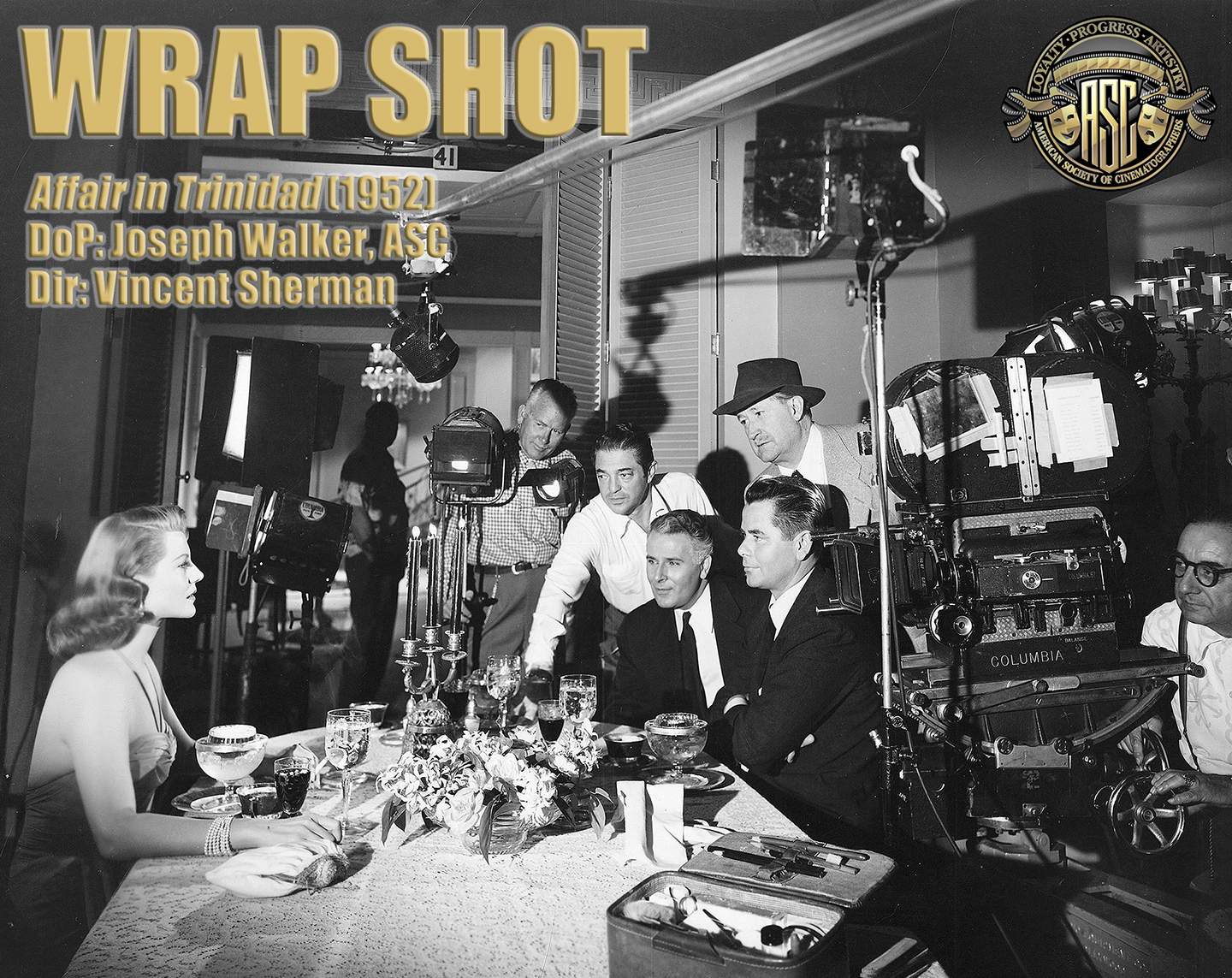

Wrap Shot: Affair in Trinidad

“I left the lot that day with restrained emotions and the innate feeling I had made my last motion picture,” said famed cinematographer Joseph B. Walker, ASC.

The film noir crime drama Affair in Trinidad (1952) — directed by Vincent Sherman and photographed by Joseph B. Walker, ASC — stars Rita Hayworth and Glenn Ford and was promoted as a re-teaming of the stars of the prior hit Gilda (1946).

Hayworth plays a nightclub singer seeking the man who killed her husband, whose brother is played by Ford.

Considered a “comeback” effort following Hayworth’s difficult marriage to Prince Aly Khan, Trinidad was the star's first picture in four years, produced under her Beckworth production banner, and, clearly, Columbia Pictures wanted one of their finest cinematographers to shoot it.

Walker had previously photographed Hayworth in the Columbia projects Only Angels Have Wings (1939) and The Lady From Shanghai (1947). He was uncredited on the latter, as was Hayworth’s frequent collaborator Rudolph Maté, ASC, while Charles Lawton, Jr., ASC was the primary cinematographer.

Born in 1892, Walker was only 60 when he shot Trinidad, but it became his final feature project before he retired. He’d joined Columbia Pictures in 1927 and worked there almost exclusively.

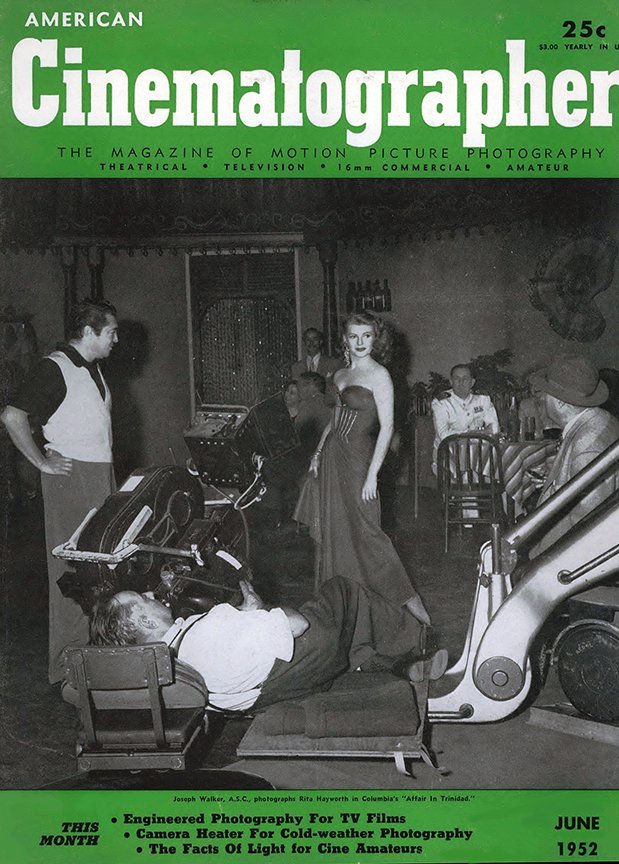

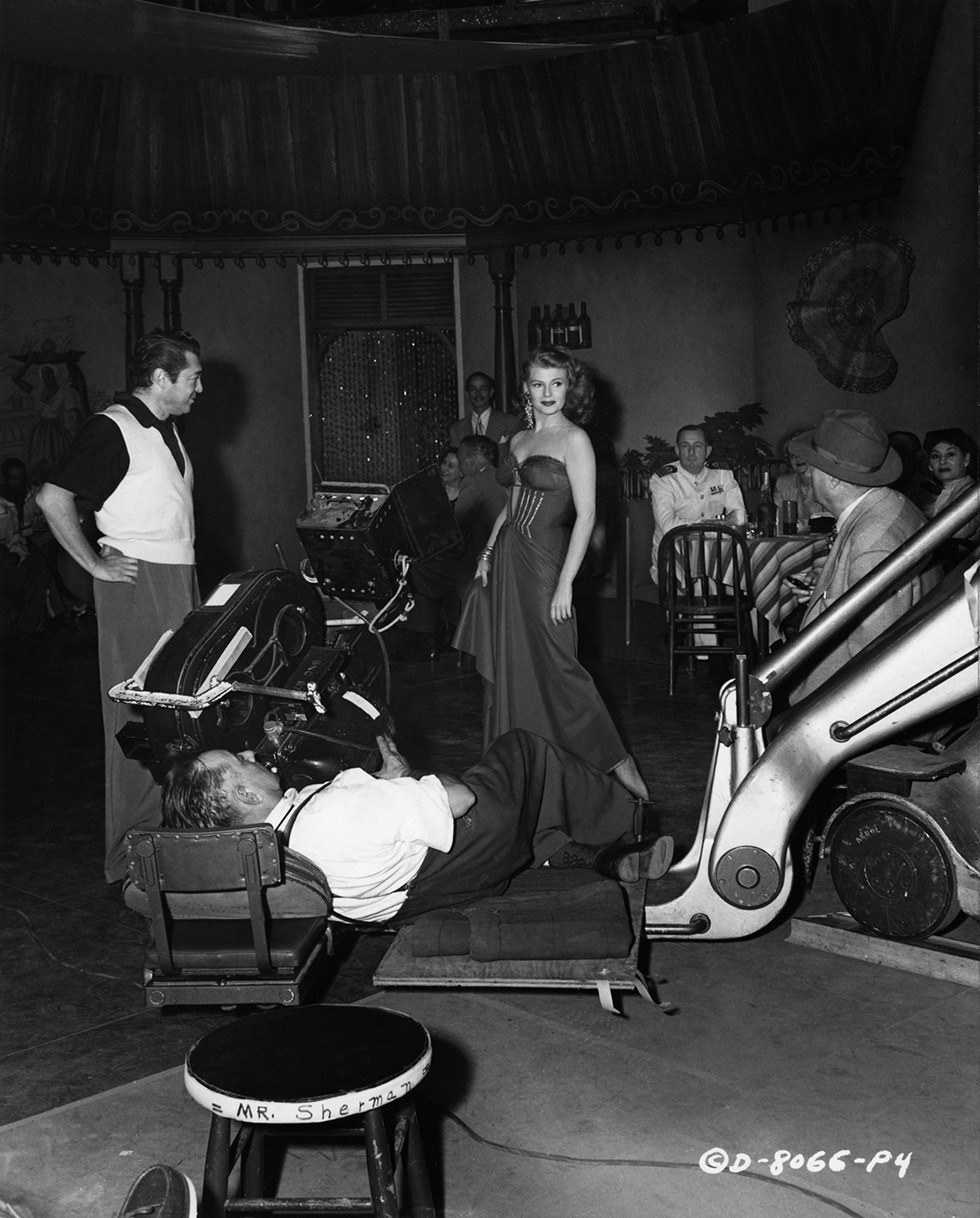

The film was showcased on the cover of American Cinematographer in June of 1952, featuring this breathless description on the table of contents:

Rita’s back and Walker’s got her! It was Columbia Pictures’ ace director of photography Joseph Walker, ASC (wearing hat) who was chosen to photograph Rita Hayworth following her return to Columbia to co-star in Affair in Trinidad. Here, camera operator Victor Scheurich focuses the low-angled camera on Miss Hayworth as she performs a torrid dance routine for an important scene in the picture.

This issue of AC contains no further coverage on the project, probably as the true behind-the-scenes story was far less exuberant.

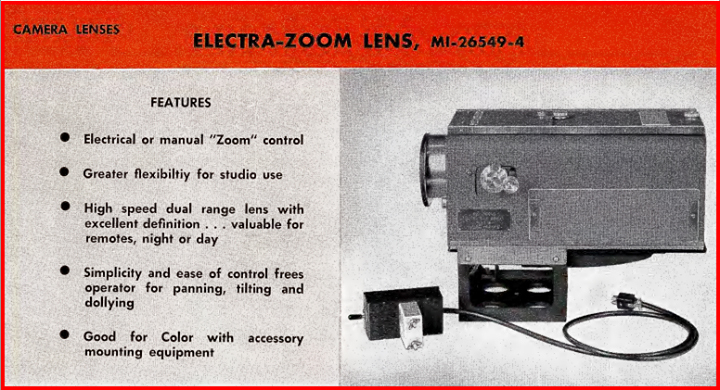

Walker — who had stopped shooting features for some time to focus on the development of his new, patent-protected Electra-Zoom variable TV camera lens, the first of which he’d just sold to NBC — had been coaxed by autocratic Columbia Pictures head Harry Cohn into photographing Trinidad after refusing several others. The cinematographer was under contract, and his studio boss wanted his best to shoot Hayworth.

“The time finally came when I could stall them no longer,” Walker later wrote in his excellent 1984 autobiography The Light On Her Face, co-authored by his wife, Juanita. “Affair in Trinidad, with Rita Hayworth and Glenn Ford, was set to start; I could find no way to get out of it.

“I thought Rita deserved better treatment than this ordinary story requiring constant rewriting and the ‘slam-bang’ method forced upon us to make it.”

During production, a bottom-line confrontation with the intimidating Cohn made it clear to Walker — still under contract with Columbia and unable to work elsewhere without his permission — that he wanted no more of the motion-picture business as a cinematographer.

“Who the hell cares how these stars look anymore?” a red-faced Cohn ranted. “You see the crap they they show on television? Worst goddamn stuff! And the public goes for it. They’ll stand for anything. From now on, we’re not wasting one cent making pictures look good! Why should we?”

Not intimidated, Walker fought back: “You’re talking about two different mediums. The viewer accepts the imperfections of television because it’s in his home and it’s free. Let me remind you, the picture is small; if it were enlarged to fill a motion picture screen, who could stand it? You can’t get away with what they are doing — and draw a paying audience. Quality of motion pictures, if anything, must be better if it is to compete with television!”

Walker was right, of course, but Cohn was unswayed: “You can’t sell me on that! Things will never be like they used to be. From now on, I’m turning them out the ’ol way. The hell with ’em!”

This blowup with Cohn proved to be a final straw for Walker, who could no longer work under subpar conditions for a man who had no respect for his artistry. Fortunately, however, the cinematographer literally had a card up his sleeve — or, rather, in his pocket — to play: A major order from RCA for Electra-Zooms. His professional and financial future was set.

After wrapping Trinidad, he told Cohn that he was done. He quit.

“Y’really mean you won’t make another picture?” the somewhat unbelieving Cohn asked Walker after making it clear that he not allow the cinematographer to shoot for any other studio.

“I’ll put it this way. I’d rather not," Walker replied. “At the present time I don’t like the way the industry is headed.”

Walker concluded his book’s brief chapter on Affair in Trinidad — entitled "The Last Picture Show” — with this: “I left the lot that day with restrained emotions and the innate feeling I had made my last motion picture. The feeling proved accurate. Though entreated many times by the studio to return during the next few years, never again did I make a motion picture.”

In 1982, Walker — a four-time Oscar nominee for his cinematography — was the first recipient of the Gordon E. Sawyer Award, presented to him in recognition of his technological contributions to the film industry by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences.

If you enjoy archival and retrospective articles on classic and influential films, you'll find more AC historical coverage here.