Deep Focus: Diopters

Understanding the use of these close-up lens attachments that can bring us extremely close to a subject or carry focus between planes.

Some of the most fascinating photographic images are those that bring us extremely close to a subject. However, the nature of optical design — and limitations imposed by physics — makes it so that a standard lens is not typically capable of focusing at a close enough distance to achieve a “macro,” or extremely close, shot. Instead, such shots are typically accomplished in one of two ways: with a special macro lens that’s been optically designed for extreme close-focus work, or with a close-up lens attachment, commonly referred to as a diopter. (There are other methods, too, but we’ll save those for another day.)

A quick note: Although “diopter” is the common term, it isn’t actually the correct one. A diopter is actually a unit of measurement in optical power — akin to inches or millimeters when referring to focal length. Although we identify specific lenses by their focal length, usually in millimeters, we don’t refer to lenses on the whole as “millimeters”; nevertheless, we’ll stick with the industry-standard usage of the word “diopter,” but technically, what we’re calling a diopter is a close-up attachment — and it’s also sometimes called a Proxar, the name used by Carl Zeiss for its series of close-up attachments.

Diopters are positive supplementary lenses. In the most basic sense, this means they’re glorified magnifying glasses. They are positioned in front of an existing lens, allowing that lens to focus on objects that are closer than its normal minimum-focusing distance. Diopters can screw into the lens’ front threads, clamp onto the lens barrel, or fit into a filter tray in a matte box. The glass element is usually a simple meniscus (curved) lens, but in some cases can be two lens elements glued together.

While we understand lenses to be identified by their focal length, diopters are specified by the reciprocal of focal length: optical power. Diopters are measured in meters so that a diopter with an optical power of 1 has a maximum focus distance of 1 meter (3.28'). This means that if you have a +1 diopter and you attach it to a lens whose focus is set at infinity, objects at 1 meter will now be in focus. Where it gets slightly confusing is that higher-power diopters reduce the maximum focus distance — so a +2 diopter on a lens set at infinity will reduce the maximum focus to 1⁄2 meter (1.64'), a +3 diopter will reduce the focus to 1⁄3 of a meter (13.12"), and so forth.

Common diopters come in +1⁄2, +1, +2, +3, +4 and +5. Fractional diopters such as +3.2 and +3.5 are also available, and some can go as high as +7.

By attaching a diopter to a lens you are, in essence, reducing the lens’ minimum focusing distance — allowing the camera to come closer to the subject — and rendering a magnified image of the subject being photographed. A lens might have a minimum focus of 3'; with a diopter, that distance decreases, bringing the camera significantly closer to the subject for a “macro” shot. And if you adjust the focusing ring to a distance closer than infinity, you can get the camera closer still. Additionally, diopters can be stacked together for higher-power magnification. Brought together, a +3 and a +4 diopter will equal a +7, making for a focusing distance of 5.5" with the lens’ focusing ring at infinity. Please bear in mind: When stacking diopters, the higher power should be closer to the lens.

It’s important to understand that most diopters are simple single-lens elements that provide little to no correction of aberrations. Rather, they can induce their own — especially chromatic aberrations, which happen when various color-wavelengths of light are improperly refracted by the lens and don’t meet correctly at a fixed focal point. When that happens, you start to see color fringing around the image. To correct for this, higher-end diopters are made with two lens elements glued together in an achromatic doublet. These diopters are considerably more expensive (and heavier), although in many cases they’re still more affordable than high-end specialty macro lenses. Some people mistakenly refer to all diopters as “achromats,” but that term is only applicable to dual-element lenses, not to the simple single-element diopters.

Each single-lens diopter will induce some chromatic aberration into the image, and stacking them only compounds the issue, so cinematographers need to exercise caution when combining diopters. To mitigate the risk of such aberrations, as a general rule of thumb you should shoot at a fairly deep stop when working with diopters — above f/4 or f/5.6, if possible. Stopping down improves the overall performance of the lens and helps to reduce aberrations induced by the diopters. Also, as the lens gets significantly closer to a subject, depth of field shrinks very quickly. If you have a subject that moves — say an insect, or a flower in a light breeze — it can be near impossible to keep it in focus when the lens is mere inches away. A deeper stop will help to increase depth of field, keeping more of your subject in focus.

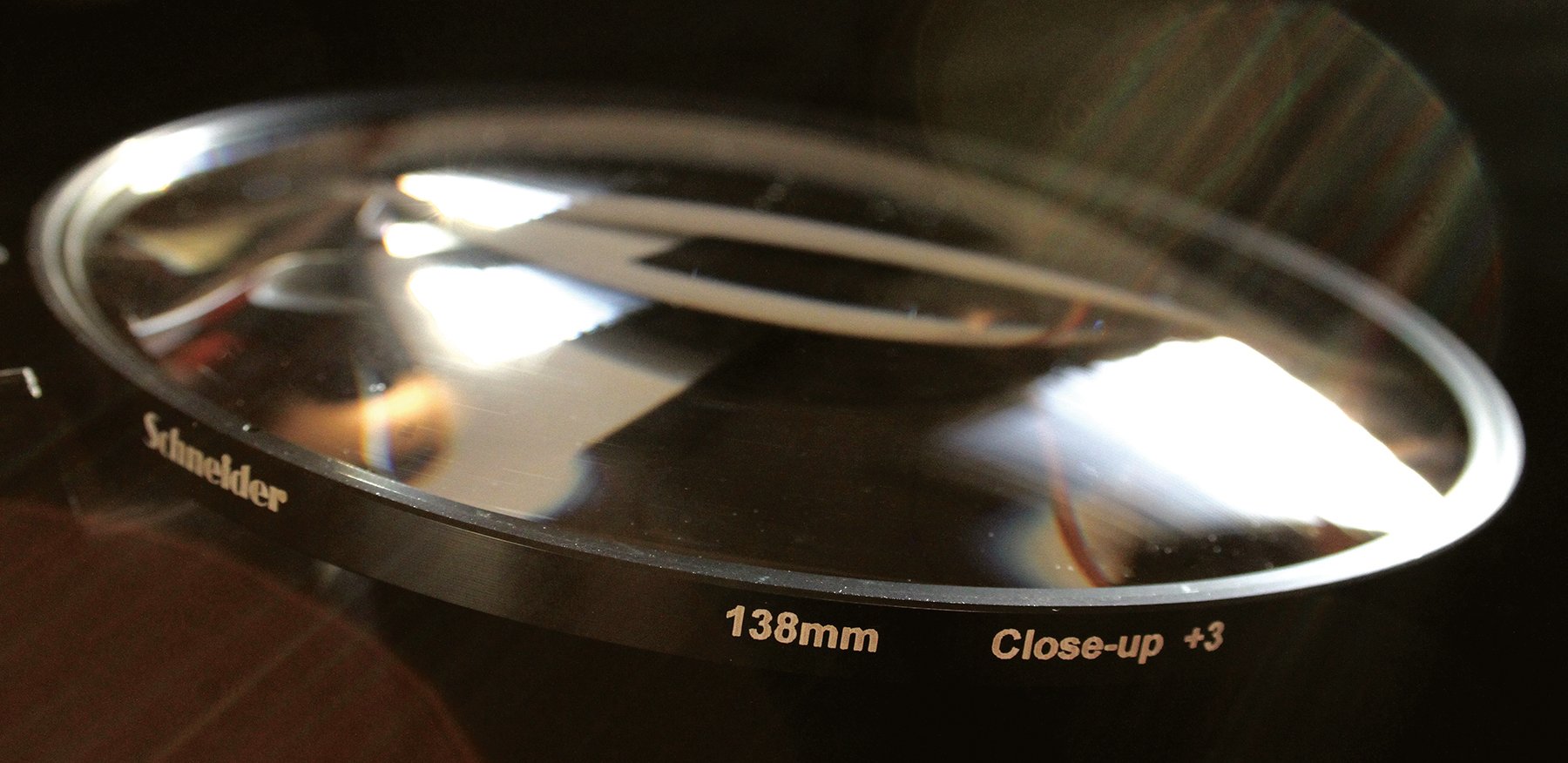

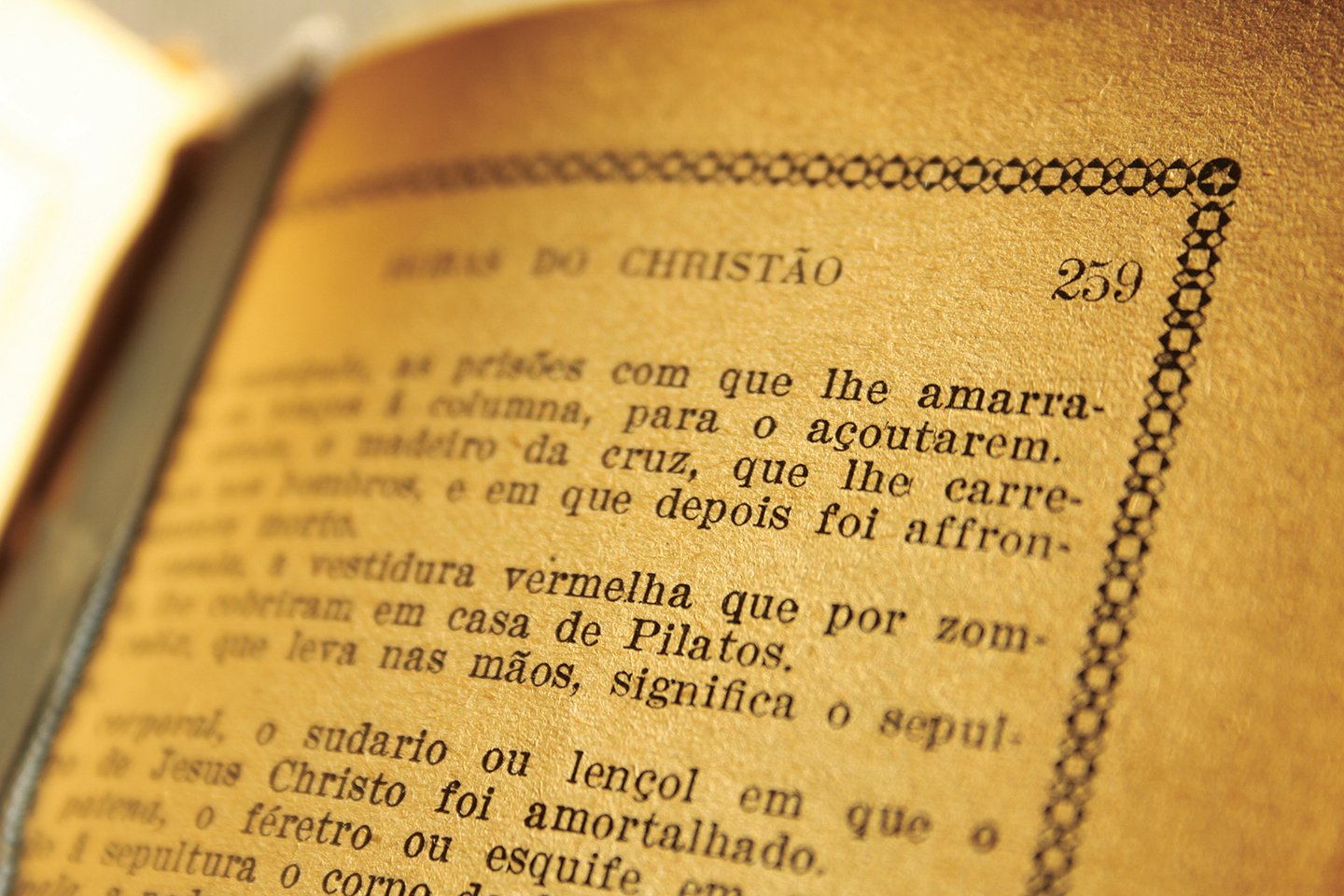

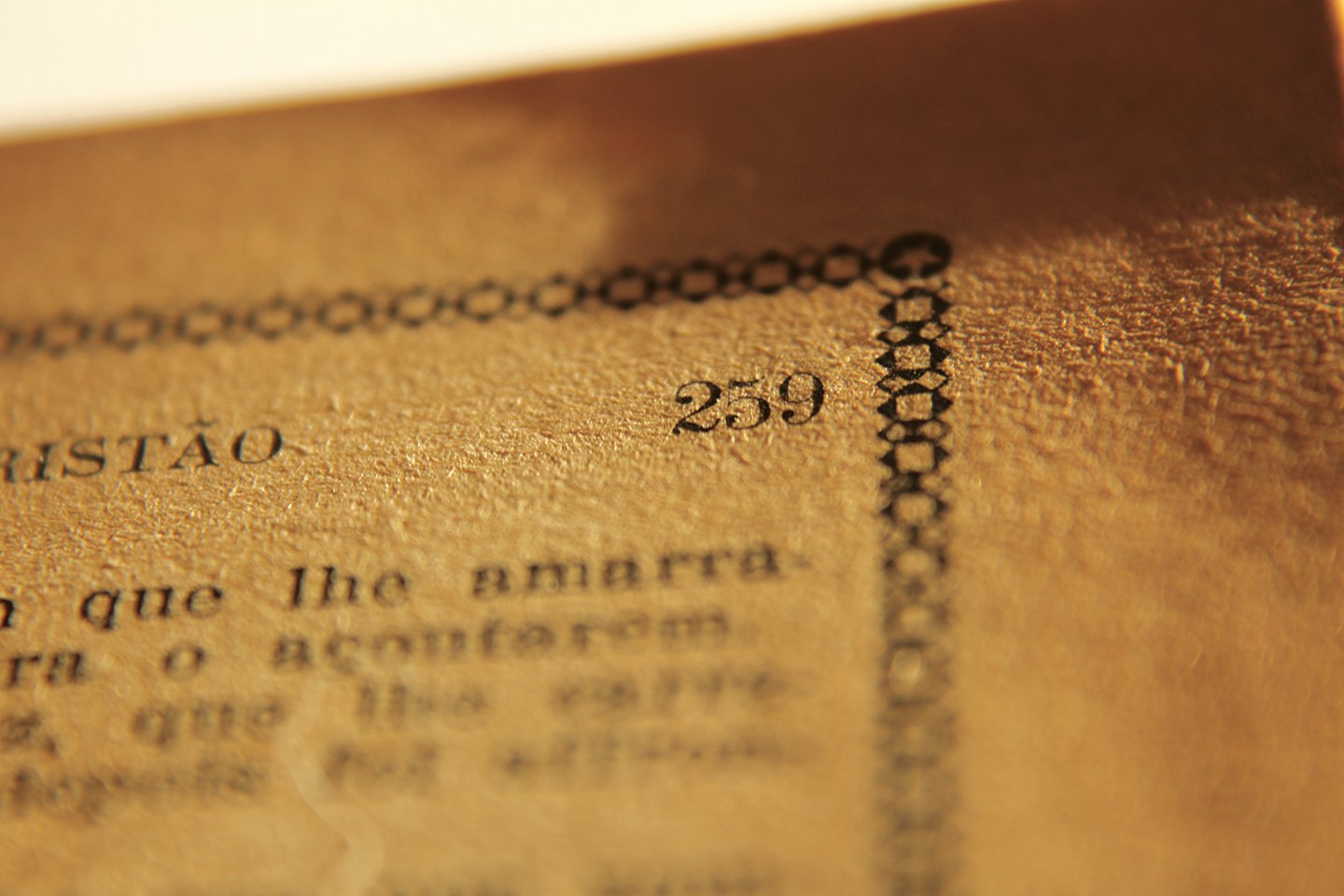

The top photo on this page, showing a page from my grandfather’s Portuguese prayer book, was taken with a Canon EOS 7D with a 55mm lens from a distance of 10 3⁄4", the lens’ minimum focus. The second photo was taken with the same gear, with the addition of combined Schneider Achromat +3 and +2 diopters at a distance of 7 3⁄4". Note that not only is the second shot much closer to the physical page, but the depth of field is extremely shallow, only a fraction of an inch. Both shots were taken at the same f-stop, and no additional optical devices were employed; the reduction in depth of field results from the camera’s closer proximity to the subject.

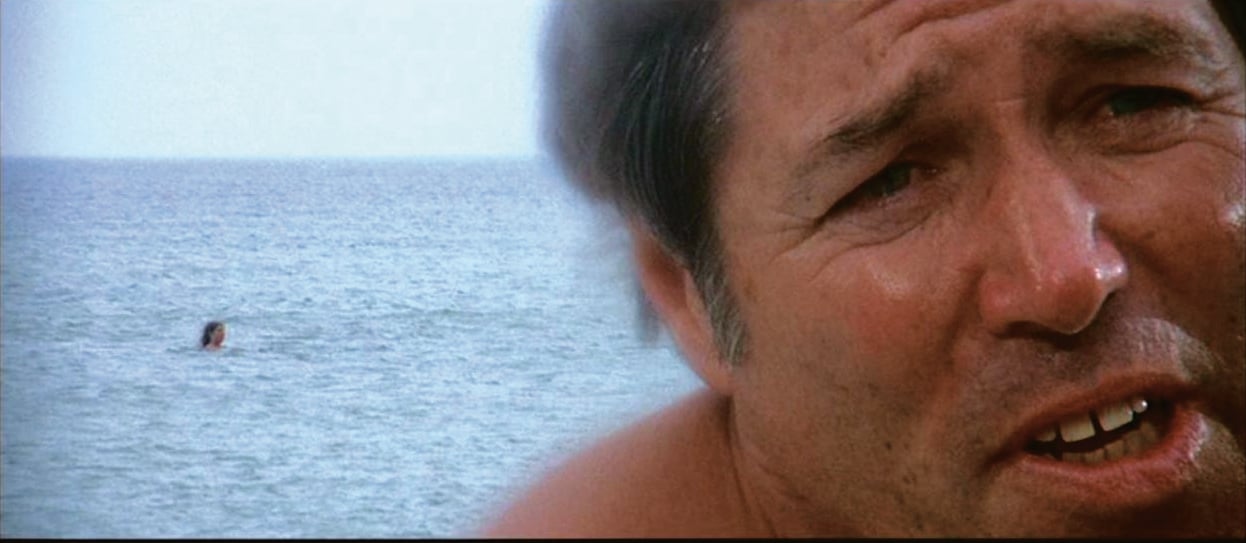

Split-field diopters are also available. As the name suggests, these lenses are literally split; they’re cut right down the middle so that the lens holder has half an open space and half a diopter, allowing the cinematographer to apply the close-focus application of the diopter to only a portion of the frame and utilize the camera’s lens, on its own, for the remainder. This results in two distinct planes of focus in the image — one distant (the open area) and one close (the diopter).

Split-field diopters also require careful application, as they create a clearly visible distortion line between the close-focus and non-affected portions of the frame. Usually this transition line can be incorporated into the artistic vision of the image or cleverly hidden through careful framing, with the transition line “concealed” along a geometric line that already exists in the shot. Using a physically larger diopter size can allow the filter’s positioning to be adjusted, which might further help the diopter’s transition edge to be aligned with some vertical, horizontal or even diagonal line in the frame — a door, a table, a corner, etc.

To allow for a range of applications, split-field diopters are available in a variety of sizes and shapes beyond the traditional half-circle. For example, there are thin strips cut from diopters that can be mounted in various positions in a holding frame; more exotic variations include center-hole diopters that have a hole bored out of the middle, like a donut.

When using a split-field diopter, it is best to set the far distance on the lens first and then slip the desired diopter strength into the matte box. Bear in mind that the two points of focus cannot be individually adjusted; to avoid driving yourself too crazy, it’s typically useful to focus the lens on the distant object and then move the closer object toward or away from the lens until it lands in sharp focus.

Split-field diopters were popular in the 1970s through the 1990s but aren’t seen nearly as often anymore. Stephen H. Burum, ASC, is well known for his use of split-field diopters on films such as The Untouchables and The War of the Roses. Other classic examples of split-field-diopter shots can be found in Jaws (shot by Bill Butler, ASC), Close Encounters of the Third Kind (Vilmos Zsigmond, ASC, HSC), The Andromeda Strain and Star Trek: The Motion Picture (Richard H. Kline, ASC) and Cape Fear (1991; Freddie Francis, BSC).

Diopters can be attached to nearly any lens, making them equally useful for fixed-lens cameras that have no macro option and for prime-lens users with a large lens kit. If you’re in the latter category, it’s best to get a set of diopters that match or exceed the diameter of your largest lens, and then purchase inexpensive step-down rings for your other lenses. This way, you’ll only need one set of diopters to work with any lens in your package.

Diopters are particularly useful with zoom lenses and older anamorphic lenses that often have fairly distant minimum-focusing distances. Even low-strength diopters can help to reduce the minimum focus to a more useful range. Schneider Optics, for example, offers fractional diopters in 1⁄8, 1⁄4, 1⁄2 and 3⁄4 strengths for slight adjustments to minimum focus without undue sacrifice of farther focusing distances.

Diopters for motion-picture lenses are also manufactured by Arri/Zeiss, Leitz, Lindsey Optics and Tiffen, among others.