SPONSORED BY: ASC Master Class

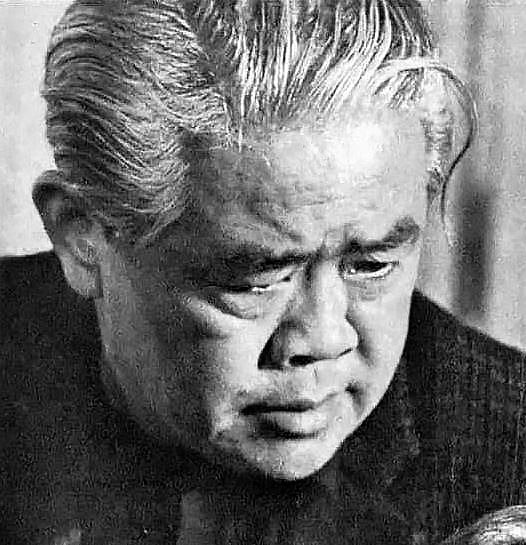

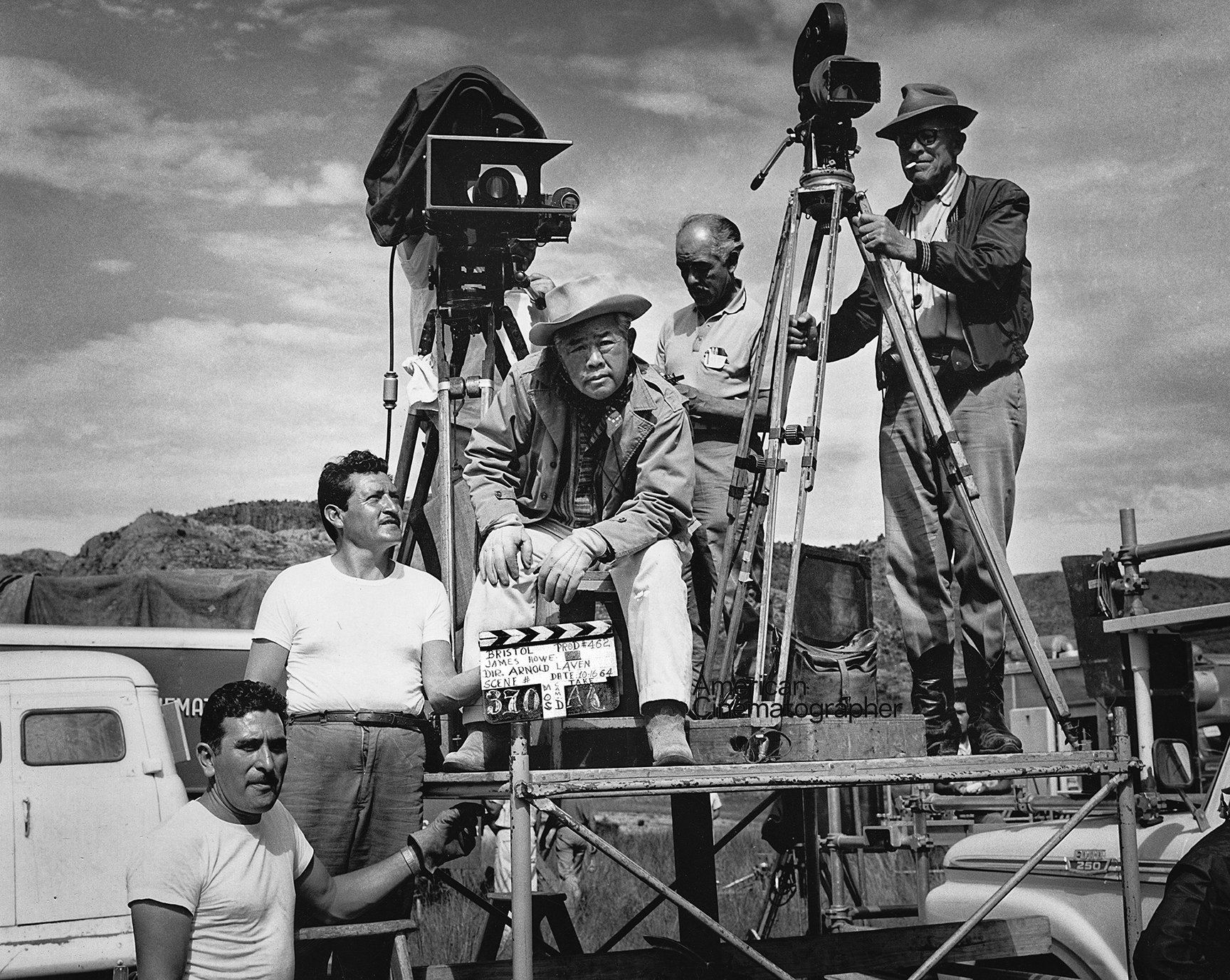

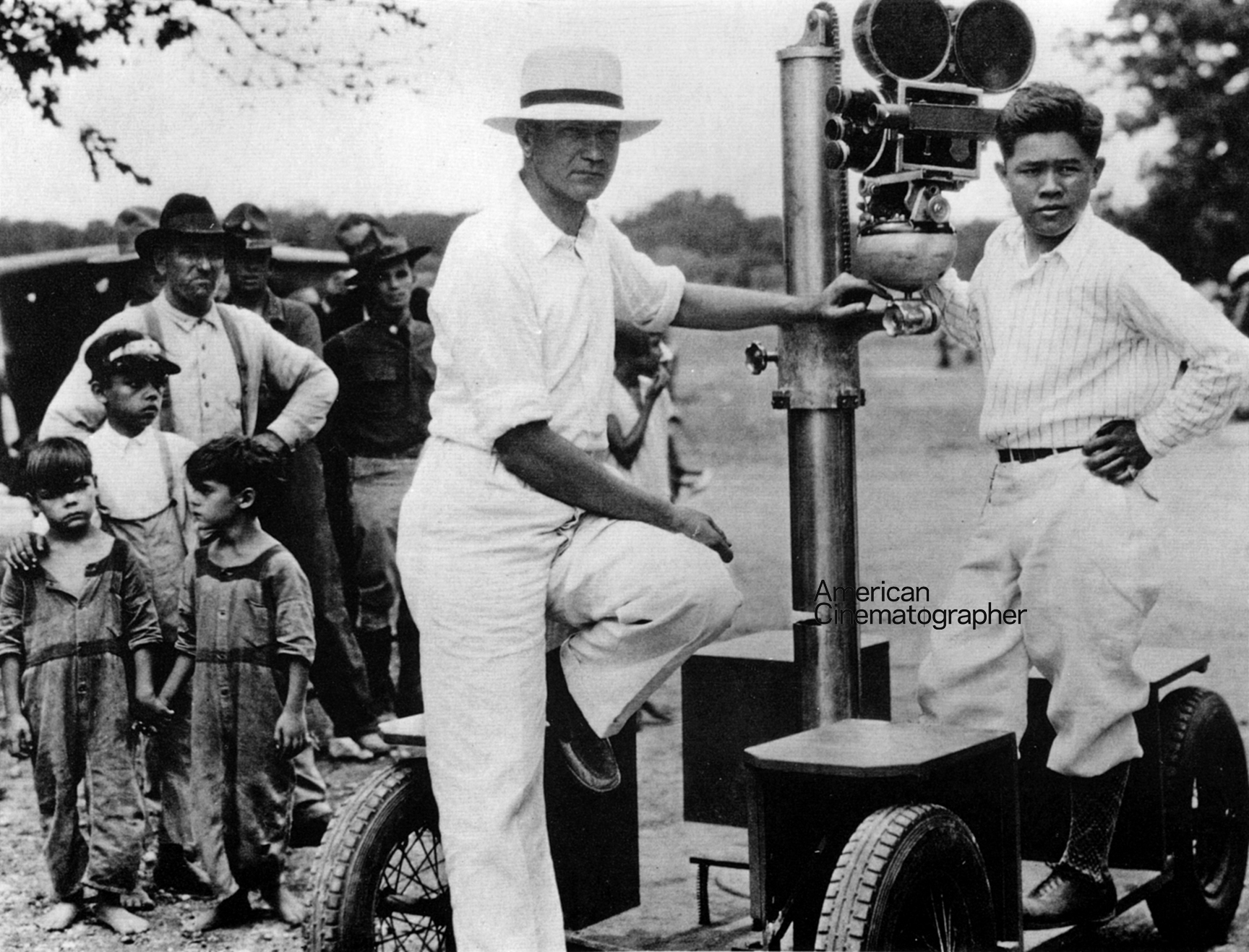

This episode features an interview with James Wong Howe, ASC conducted by film archivist and Society associate member Kemp Niver at the cinematographer’s home on April 3, 1964.

Niver received the ASC President’s Award in 1991 for his work transferring the paper print collection of historic films from the Library of Congress to celluloid film.

Howe was a pioneering cinematographer in Hollywood, nominated 10 times for the Academy Award for Best Cinematography and winning twice, for his stunning black-and-white work on The Rose Tattoo in 1955, and Hud in 1963. From 1922 to 1975, Howe photographed over 130 motion pictures, many of them film classics.

In this wide-ranging interview, Howe discusses his long career and provides the listener with a unique glimpse into his creative mind.

Also mentioned in this episode are stories from our September 2022 issue:

In a special feature on wildlife photography, wildlife filmmakers share their perspectives on capturing the natural world.

Director of Photography Edward Roqueta sheds light on the illicit jaguar trade in the award-winning documentary Tigre Gente.

Cinematographer Anisia Uzeyman's birth country of Rwanda provides inspiration for the Afrofuturist fantasia Neptune Frost.

The career of Academy Award-winning cinematographer Robert Elswit, ASC is profiled.

Follow American Cinematographer on Facebook, Instagram, Vimeo and Twitter.

Kemp Niver 1:14

This is an interview with James Wong Howe at his house on April 3, 1964. And it's about his progressive life behind the camera. Now, the first question I want to ask you, James is how did you first get interested in photography? We're not talking about moving picture camera work, but how did you get interested in photography?

James Wong Howe, ASC 1:40

Well, let me see now. That goes way back, about 1907 or eight, when I was just a young kid.

Kemp Niver 1:55

Where was that?

James Wong Howe, ASC 1:56

Up in the state of Washington, little town called Pasco.

Kemp Niver 2:00

Pasco.

James Wong Howe, ASC 2:01

That's that's where when my father first came over this country, they were building the Northern Pacific. And he worked on the railroad. And so, I was born in China, you see?

Kemp Niver 2:14

I didn't know that.

James Wong Howe, ASC 2:15

Yeah, I came when I was five years old.

Kemp Niver 2:18

What part of China were you born?

James Wong Howe, ASC 2:21

Guangdong Province.

Kemp Niver 2:22

Guangdong?

James Wong Howe, ASC 2:23

Yeah.

Kemp Niver 2:23

Oh, yeah.

James Wong Howe, ASC 2:24

Yeah, I had a little little pigtail when I first came over.

Kemp Niver 2:28

You're kidding!

James Wong Howe, ASC 2:28

This was before. Yeah. This was before China became a republic.

James Wong Howe, ASC 2:35

Sure

James Wong Howe, ASC 2:37

So I ran away.

Kemp Niver 2:38

Your grandfather was gonna take you to

James Wong Howe, ASC 2:43

Yeah.

James Wong Howe, ASC 2:44

Well, anyway. I bought a little box Brownie. And it cost a dollar to... It didn't have a finder. I bought it in a drugstore. I remember the man's name who owned the drugstore. The name was John Sullivan. So I bought this camera and took some pictures. And I asked him how to develop it. So you know, he told me go down and turn off the light in the basement, and took some developer and take unravel this and hold it up and just do it up and down and count so many counts. See? So I did that.

Kemp Niver 3:31

Was this your first roll of film?

James Wong Howe, ASC 3:32

Yeah. And it turned out, after got to counting the number of counts, I turn on the light and I held up the piece of thing there was red on one side and black on the other. Well, what I did is I developed the wrapper. So I ran back to him and said look- He said, Well look, you develop this? But how can I tell in the dark? He said, Well you moisten your fingers and you touch the end and then if it's a little sticky, that's it. Now I go and buy another roll. This time I go and take some pictures, and went through the same procedure

Kemp Niver 4:20

Ruined your whole life.

James Wong Howe, ASC 4:21

Took pictures of my brother and sister, you know, but most of the heads were cut off and some had heads in them.

Kemp Niver 4:41

Well, they still don't.

James Wong Howe, ASC 4:44

And so he didn't like it. He said, Well, look if you're gonna take pictures, he said, it'll be good if you got the heads in there. Taking out heads, that's bad. So I told him, and he gave me, bought a Brownie now with a finder...

Kemp Niver 5:01

A little finder on it.

James Wong Howe, ASC 5:02

That's how I became interested in photography. And then I always had a camera.

Kemp Niver 5:08

You had a camera photographically, then you started out with a box Brownie. Most of the cameraman alive today that have worked as professionals got ruined by Eastman. They used to sell these little cameras for a dollar.

James Wong Howe, ASC 5:23

And then right later on, I got little cameras now. And then I remember the the...

Kemp Niver 5:30

You were a very small boy at this time.

James Wong Howe, ASC 5:31

Yeah, I was kid.

Kemp Niver 5:33

Ten, twelve?

James Wong Howe, ASC 5:34

Ten, twelve years old. So then we go through the different phases of with a Kodak and taking pictures...

Kemp Niver 5:46

Well now, did you get into interested in photography professionally as a still cameraman? As a still photographer?

James Wong Howe, ASC 5:58

Well, what happened was I came down here in Los Angeles. Now we're skipping a lot of period but not... didn't have in mind to get into the movies.

Kemp Niver 6:09

All you have is... Your father was working for the railroad and then your whole family moved down, or did just you...

James Wong Howe, ASC 6:14

No, it's just me. See, my father had passed away during the meantime, he passed away around 1914.

Kemp Niver 6:22

Before...

James Wong Howe, ASC 6:22

So yes, that's right. And then I went to live with my uncle for a while in Astoria, Oregon. And from there, I went to San Francisco. My ambition was at the time, at that time was to learn flying. And there was a flying school down there, San Francisco, I think was in Redwood City. But I came down, but my money ran out and then I came down here. Well, what did I do? I didn't have any trade, you know? I just took any kind of job. A job as bus boy and and I finally wound up with a job delivery boy for commercial photographer.

Kemp Niver 7:10

Which one was it?

James Wong Howe, ASC 7:10

Raymond Stagg.

Kemp Niver 7:12

Stagg?

James Wong Howe, ASC 7:12

Yeah. Used to have his studio down on Hill Street, Hill and Eighth to Ninth. And I used to ride a little motorcycle, little Cleveland motorcycle around delivering pictures. I worked for him for oh... this was in 19... latter part 1916. Now, I work with him about several months or more. And something happened, I got fired. Some Chinese man wanted to go back to China. He wanted some passport pictures. So I told him I'll make them for him and I took him up to the studio there, at Stagg's, late one evening and had all the lights on, taking pictures and then Ray Stagg came in, and I had his best lens and he didn't like the finger marks all over it.

Kemp Niver 8:14

James Wong Howe, ASC 8:15

So anyway, I got let go. So I was down around Chinatown. I used to down there have, you know, eat on Sundays and meet some of the boys. I didn't know many people. So, they were making a movie. A comedy got people running around. And I looked at the cameraman, and he had his cap backwards, grinding away. And who do you know who it was? It was Len Powers

Kemp Niver 9:21

Just to say hello.

James Wong Howe, ASC 9:22

Oh yeah. And that see it was Len Powers, he was a cameraman. And I said hello Len. He said, Oh hi, kid. He says, When I see you before? I said, Up in Pasco, Washington. I told him that night and he says Yeah, he says, What are you doing down here? I said, Well, nothing. I'm looking for a job. He says, You oughta get into this racket. This is very good. He says, I get $50 a week and I'm doing this. How do I get in? So he told me go to the studio and ask for whoever's head of the camera department and might get a job as an assistant. And that consists of carrying equipment, you know, and holding up a slate, what they do. Well, a couple of months went by, I think I went out to, came out to the Lasky Studios, it was called Lasky's Famous Players, on Vine Street. I went up and asked for the information desk... Oh they said, Yeah, you want to see a man by name Mr. Wyckoff. Alvin Wyckoff

Kemp Niver 13:36

A swamper in the camera department.

James Wong Howe, ASC 13:38

That's right, I was a swamper. Well, the boys used to bring their cameras down. And they want to, you know, this was the day before the union, so they used to work late. Come early. Would leave the cameras there and asked me if I'd wipe them off for them, you see? So I did.

Kemp Niver 14:04

Try to learn about cameras.

James Wong Howe, ASC 14:05

Yeah. Wiping them off.

Kemp Niver 14:07

What were some of the cameras they were using in those days? Mostly Pathés.

James Wong Howe, ASC 14:10

Mostly all Pathés.

Kemp Niver 14:14

DeMille's people usually used Pathés.

James Wong Howe, ASC 14:19

Well, anyway, it was a Japanese cameraman, Henry Kotani, was there, used to photograph Sessue Hayakawa, who was a big star in those days. Henry was, they tell me he was quite a good cameraman, but they had a hard time keeping assistants with him. I don't know why. So they thought they'd put me with him. I'd get along.

Kemp Niver 14:52

James Wong Howe, ASC 14:53

Yeah. Well, I worked one picture with Henry

Kemp Niver 15:24

Did they use a Pathé camera?

James Wong Howe, ASC 15:25

Yeah.

Kemp Niver 15:25

Can you remember the kind of lens they used?

James Wong Howe, ASC 15:28

Oh, I think it was a Goerz lens or a Zeiss Tessar. I forgot which one it was. I think the lens was a 50mm.

Kemp Niver 15:40

3.5, or 4...

James Wong Howe, ASC 15:42

3.5 or 4.5 or something like that. Well, that was my first picture with Henry, Roy Neill, and Lila Lee. This must have been...

Kemp Niver 15:58

World War I.

James Wong Howe, ASC 15:59

Yeah, around then. It's around the oh... early part of spring of 1918. Probably because I went there around the fall of 1917. This was the World War I. And now I remember working with Henry when the Armistice Day, see, I remember, gee, that was quite something because I live downtown above this Third Street Tunnel there on Hill Street. And it was quite a racket. I used to get on the street car and come out to Vine and used to pass that wonderful big set that

Kemp Niver 17:41

But you were doing what you were

James Wong Howe, ASC 17:43

It worked out pretty well. So...

Kemp Niver 17:47

Did you work as an assistant? Did you load and unload cameras? And did you work in the developing room? Or did you learn anything about...

James Wong Howe, ASC 17:54

Oh, yeah, well, we learned you know how to wipe that camera off and and load and unload. And also, we had to load and unload the stills, see there were 8x10 glass plates. They didn't have a still man in those days. You know, just the cameraman. He took the stills. But the assistant had to pack all his stuff.

Kemp Niver 18:19

You said your first the first man you worked for was this Japanese cameraman. Where do you think he learned his photography in this country?

James Wong Howe, ASC 18:28

He learned from Alvin Wyckoff.

Kemp Niver 18:30

Oh, I see.

James Wong Howe, ASC 18:30

He was an assistant with Alvin Wyckoff. See? Well, I didn't work with Henry very long because we didn't get along. So...

Kemp Niver 18:39

Did you have to develop to help him develop the glass plates? Or did he do that himself?

James Wong Howe, ASC 18:44

Oh I think in those days I think they had a still developing place in the lab. But I don't remember him developing them. But anyway, I develop my own pictures because I went and bought a 5x7 view camera downtown in one of these pawn shops and I used to take pictures for the extra people, you know, and bit players. You see, in those days, Kemp, they didn't have agents.

Kemp Niver 19:23

I've looked at some older trade magazines, and it's just like a phone book.

James Wong Howe, ASC 19:27

That's right, each studio had their own casting department. Then people would leave their pictures there. Full length, one full face, and profile you know each and in the back they wrote down their name, address, and what they could do: ride a horse or play polo, and all this stuff. So they needed pictures from time to time. And I remember making pictures of Bill Boyd and all these fellas.

Kemp Niver 19:58

He was a little boy...

James Wong Howe, ASC 20:01

And they pay me 50 cents a piece you know enlargement and you know I made pretty good money. At same time, I learn how to make good portraiture, and that's what a close-up is anyway. A close-up is is like a good portrait you know?

Kemp Niver 20:22

That's right.

James Wong Howe, ASC 20:23

If you learn how to light a portrait you can light a close-up.

Kemp Niver 20:26

Well, as a professional cameraman of some note if you'd say that man had to learn photography the thing that if you had to find somebody in a hurry you go look for a still photographer that took portraits.

James Wong Howe, ASC 20:38

Yeah.

Kemp Niver 20:38

He'd understand lighting.

James Wong Howe, ASC 20:39

Kemp Niver 20:42

Oh yeah, oh yeah.

James Wong Howe, ASC 20:43

I got along very well. And then I became Alvin Wyckoff's when his assistants... Of course, DeMille those days always had two or three cameras. So I was second on some pictures that, oh, gosh, who else was cameraman? I remember making the Irvin Willat picture.

Kemp Niver 21:09

Tell me something. When did you first really feel that you understood how you could get or capture a scene photographically? So that, when do you do you think that you first started to get a feel for photography so that you could throw a key light in and a fill? Did you, before you actually started as a boss cameraman?

James Wong Howe, ASC 21:35

Oh, yes, I think I began to know how to light faces when I was making these pictures. And then I used to, during... after picture, I used to make these title backgrounds photographs, soft focus. You see, I had bought a meniscus lens.

Kemp Niver 21:56

Yes.

James Wong Howe, ASC 21:56

From an optician on Hollywood Boulevard. I think he's on Highland now. His name was

Kemp Niver 22:35

Meanwhile back at the...

James Wong Howe, ASC 22:36

As time went by... make it an hourglass, sand glass, you know. All these things are illustrative backgrounds for the titles. Well, that gave me a great... a fine education in composition.

Kemp Niver 22:52

This was done at the studio or for Al?

James Wong Howe, ASC 22:56

Anybody I worked for with in those days to make a picture, and that's when I was even a second camera, you know.

Kemp Niver 23:02

Oh this is interesting. So you started shooting titles?

James Wong Howe, ASC 23:05

Yeah,

Kemp Niver 23:05

Today it would be like a title company.

James Wong Howe, ASC 23:07

I make a Western, I... during... after lunch or something, I'd see a nice cloud or a cactus, I'd shoot this out of focus. Then, at the end, I'd make these things, I'd show them to the director. I said, ‘Look would you like this for title background?’ He says, ‘Oh yes swell.’ I give it to him for title backgrounds.

Kemp Niver 23:26

Yeah.

James Wong Howe, ASC 23:28

And then...

Kemp Niver 23:29

Did you have, you have a little bench that you set the moving-picture camera up?

James Wong Howe, ASC 23:34

No, but I shot these on a 5x7.

Kemp Niver 23:37

Oh, I see.

James Wong Howe, ASC 23:38

You see? And then I gave them the negative... now they would enlarge them and then they'd use them for... The title department would use them later. Well, that gave me a good education in...

Kemp Niver 23:51

Composition.

James Wong Howe, ASC 23:52

Composition. And also lighting...

Kemp Niver 23:54

It started you thinking about it.

James Wong Howe, ASC 23:56

It started me thinking, started me to be seeing, you know, use my eyes to visualize and...

Kemp Niver 24:02

The way a camera lens would see something.

James Wong Howe, ASC 24:05

So, now... Oh, then Bert Glennon

Kemp Niver 24:37

James Wong Howe, ASC 25:40

Yeah! I says, I'm not supposed to tell you those things. He says, Why not? He said, Why the hell not? He said, Because, you're you're... you're working for me, you know? And if you see anything wrong, you better tell me, see? From now on, anything wrong, you tell me. But I was very hesitant, because, you know, your discipline in those days. Boy, when you're an assistant, that's something they don't have today. Boy, when you're the assistant, you know the moves, you know where you sat... and if you're a second camera, you just don't open your mouth much until...

Kemp Niver 26:20

All you were doing is backing up your boss.

James Wong Howe, ASC 26:22

Yeah. So, by God, there was... a message came back. They couldn't see those scenes, they had to retake them, see?

Kemp Niver 26:34

I guess he wanted to know how you knew.

James Wong Howe, ASC 26:36

Yeah. And, then, so,

Kemp Niver 27:21

And that was on Catalina?

James Wong Howe, ASC 27:23

Yeah.

Kemp Niver 27:25

Did you come back to the studio and shoot anything?

James Wong Howe, ASC 27:27

No, this was in the studio. We were at Catalina

Kemp Niver 27:43

What kind of money you make now, $50 a week or maybe more.

James Wong Howe, ASC 27:47

$15.

Kemp Niver 27:48

Oh, you're still at $15 a week.

James Wong Howe, ASC 27:49

Yeah. I didn't make $50 a week until I got to be a cameraman. That's what I got paid first. I became one of the assistants with Alvin, and then I think I worked with a boy named Harold Schwartz then. He's passed away. There was another chap that came to work with us. George Meyers, I don't know what happened to him.

Kemp Niver 28:18

But you're working for Lasky at that time.

James Wong Howe, ASC 28:20

Yes, and...

Kemp Niver 28:21

Your first few years were at Lasky.

James Wong Howe, ASC 28:24

So, I finally graduated to become a what we call a second camera. See, we didn't have camera operators in those days because each cameraman operated his own camera... cranked by hand.

Kemp Niver 28:44

Now you had the second camera that had the master camera and the one alongside of it for the...

James Wong Howe, ASC 28:49

Foreign version.

Kemp Niver 28:50

Foreign version.

James Wong Howe, ASC 28:51

Negative, they called it.

Kemp Niver 28:52

They didn't make duplicate negatives.

James Wong Howe, ASC 28:54

That's why we had the second camera. When the first cameraman would set up, line up, we'd get as close as we can and try to duplicate the same setup. That's for the foreign negative.

Kemp Niver 29:07

And same stop, so that it'd be the same contrast.

James Wong Howe, ASC 29:10

And we watch how you you know lit, and by that time we've already learned how to crank, you see. Well, and used to every chance I have these cameras I start cranking them and... and well, as a matter of fact, I had a little thing in my room I used to crank. A bolt from is little old... found one of these little old secondhand stores... a little coffee grinder thing, you know, you have in the home. I just set it on the edge and just took that and it just cranked.

Kemp Niver 29:41

Just to smooth your arm and wrist.

James Wong Howe, ASC 29:43

That's right, get the crank and we'd count the footage. One foot a second, see? We used to say, One and two and three and... Because, in those days, they didn't have counters on some of the cameras. So I could be anyplace and I would hear Mr. DeMille say, All right, camera! And I hear him say, Cut. I could tell him how many feet are run. Well, then...

Kemp Niver 30:14

Just instinctively just started counting in your head.

James Wong Howe, ASC 30:16

Sure! Then Mr. DeMille used to rehearse. So he had an idea. And you've got one of these reader counters to put on the camera and he had a

Kemp Niver 30:40

How many feet. Why did you think he wanted to know that?

James Wong Howe, ASC 30:43

Well, I think for his timing.

Kemp Niver 30:45

I see.

James Wong Howe, ASC 30:46

See, whether the scene is too long, or whether it was he could shorten up whether you know, you want a timer. Well, I kinda...

Kemp Niver 30:54

He was getting pretty specific in the early days. This guy was thinking all the time.

James Wong Howe, ASC 31:00

Oh yes. Because now, I mean, he did a very interesting thing in those days. I remember he had a picture with Theodore Roberts, played the blacksmith

Kemp Niver 31:30

Especially with a dramatic film.

James Wong Howe, ASC 31:32

I don't know what they did. They had a process going, hand checkers

Kemp Niver 32:00

Are you still on Pathé cameras?

James Wong Howe, ASC 32:02

Yeah. But he had a Bell & Howell

James Wong Howe, ASC 32:04

Yes.

James Wong Howe, ASC 32:04

And I had a Pathé.

Kemp Niver 32:07

You know there's a picture of you on the wall at the ASC, of you two together.

James Wong Howe, ASC 32:12

Yeah. Oh, is that right? Yeah, well, that was in probably 19... oh, 1920, ’21.

Kemp Niver 32:20

See, that wall in the pool hall is all filled with pictures that Arthur Miller

James Wong Howe, ASC 32:29

I may have some downstairs I might find.

Kemp Niver 32:32

Yeah. It's good thing.

James Wong Howe, ASC 32:35

Well, anyway, I was just second. And then, how I became a cameraman was really when I was taking some stills one day and Mary Miles Minter walked by. I made some... two, three shots of her. I developed them, enlarged them and gave them to her later and there about fourteen prints and she liked them. A couple months later, I'm called into Mr. Charles Eyton's office. Well Mr. Eyton was the general manager...

James Wong Howe, ASC 33:09

Yes, for Lasky.

James Wong Howe, ASC 33:10

Yes, at that time. I thought, Oh, something happened now.

Kemp Niver 33:21

Oh boy, $20 a week!

James Wong Howe, ASC 33:24

He says, Well,

Kemp Niver 34:02

How did you do it?

James Wong Howe, ASC 34:04

Well, I'm coming to that. I said, Gee, yes. I walked out. She says Oh, we're gonna make a picture in two, three weeks. And I walked out and I said, My God, how did I make her eyes go dark? So I went back there to where I made the picture. And I stood where she stood, and I stood where the cameras stood. And I remember I had a key light up on one side, and the fill, and if we want to keep all the light out

Kemp Niver 36:02

James Wong Howe, ASC 36:02

He makes your eyes go dark. But then I became a genius. You know, everybody had light eyes and wanted me to...

Kemp Niver 36:11

You're a sorcerer.

James Wong Howe, ASC 36:12

So I had offers in, you know, I was getting $50 a week and now I'm offered $75, and $100 a week. And I go back and tell Mr. Eyton. Well, you know when they get you in there by the time they get through with you, you work for nothing. Mr. Eyton says, Now, Jimmy, I'm... you know, I tell you what I’ll do. I'll give you a contract. And I always made big pictures in those days I work with him. After Ms. Minter, I worked with

Kemp Niver 36:47

You started out on a Pathé camera, then you went to a Bell & Howell

Kemp Niver 36:58

When sound came in.

Kemp Niver 36:59

When sound came in. Were you out at MGM then?

James Wong Howe, ASC 37:01

I was at MGM and I made a trip to China. I took some time off. I went over there around 1928 for a few months and when I came back and sound had got a hold. And, by golly, you know it was hard to get a job unless you made a sound picture.

James Wong Howe, ASC 37:21

And you never made one.

James Wong Howe, ASC 37:22

I never made one, you see? So I went around here for about a year, year and a half without making a picture. But what I did was I made... produced, directed, and photographed the picture my own

Kemp Niver 37:43

A sound picture?

James Wong Howe, ASC 37:45

On records, on phonograph records, and they called it... they call it the Kellum Process. Terry Kellum. He's still around, he's the one who recorded it. And we made this full-length picture. And it cost about $12,000, $15,000. Japanese talking. And got the money back in this country but in Japan it didn't go because the Japanese talk different over here than in Japan. They laughed it off the screen.

Kemp Niver 38:19

The Japanese fellow that was the star in it was an American Japanese man. That wasn't very smart of you guys.

James Wong Howe, ASC 38:26

One boy was a waiter down here at a Japanese restaurant down here, near... near Gardner

Kemp Niver 39:55

That's 33 years ago.

James Wong Howe, ASC 39:57

That was my first sound talkie. And there's low key... And I shot everything with a 24mm lens, see?

Kemp Niver 40:06

The whole picture.

James Wong Howe, ASC 40:08

The whole picture, I don't think I use anything wider than the 30mm or 32, 30mm. But I use the 24 millimeter and it gave it that, we had the perspective... and it gave it that long perspective, forced perspective, on this ocean liner. And

Kemp Niver 40:47

It's amazing.

James Wong Howe, ASC 40:49

I remember Mr.

Kemp Niver 41:03

Well, lens makers were learning how to bring out good glass that was fast, you know. You guys were finally getting down to a place where you had 2.5 maybe a 2.8 lens and you could stop down you get a little heat in there, you know...

James Wong Howe, ASC 41:23

But, you know, those old lenses those f/3.5 or Heliar and all that stuff, they're good lenses.

Kemp Niver 41:28

Today they're good lens. Well, what the heck, optically-speaking, and mathematically-speaking, you can't find a better depth of focus point than 3.5.

James Wong Howe, ASC 41:39

That's right. But the lens should be made... Now, I think when I use a stop f/5.6 outdoor, the lens should be made for f/5.6. You take an f/1.9 lens and step down to 5.6 or 11 or 16, you're not using what the lens was made for.

Kemp Niver 41:57

Well I don't know that I don't consider camera... I just work at it, but photography is a quite an art, but I don't ever... All my lenses, of course, in the type of work I do have got to be fast, but outside, I'll stick neutral-density filters to keep the lens open.

James Wong Howe, ASC 42:19

That's right, well that's why we should should our close-ups you know wide open you see. Today, they stepped down more. Today, with the like Panavision and large screen people want more sharpness.

Kemp Niver 42:35

Depth of focus. While we were on your your early sound pictures, were you working in a doghouse?

James Wong Howe, ASC 42:42

No, I wasn't. I mean, I but that lens got me that picture. Transatlantic was a big hit. And it's gotten rave notices. And that got Bill Howard, William K. Howard out of the dog house, and I got a contract from Fox. I think I had a three-year contract. And I went from Fox to high places, except I never worked at Universal... or Republic.

Kemp Niver 43:13

Well, you've been a big-league cameraman for 30 years and once you're a big-league cameraman when they usually don't let go of you anyway.

James Wong Howe, ASC 43:22

Yes, and I've been mostly... I was under contract at Fox. Selznick. MGM. You know, then I went to England for a year, came back, and I went to Warner Bros. I was at Warner Bros. 10, 12 years and from then on I went freelancing.

Kemp Niver 43:47

Well you're at that age bracket now in your particular league that you work just as long as you want to work.

James Wong Howe, ASC 43:53

Yeah, well, I made a couple a year now. And I just finished The Outrage

Kemp Niver 44:07

Tell me something. This isn't part of the interview, but it'll be on the... In Hud

James Wong Howe, ASC 44:23

Well, you know what, Kemp, I didn't use a filter on Hud. I used it once. I think it was a

Kemp Niver 44:51

When'd you first start learning about filters? Just about the time anybody else did?

James Wong Howe, ASC 44:56

I start learning about filters when I first used panchromatic on a picture called The Alaskan with

Kemp Niver 45:12

You didn't start fooling around with filters then until panchromatic film came around.

James Wong Howe, ASC 45:15

That's right. Because orthochromatic wasn't much good anyway. Now when we shot the interiors at the studio, I used orthochromatic film,

Kemp Niver 45:21

You knew.

James Wong Howe, ASC 46:06

I finally figured it. I said, God, it must've been those red filters, you see?

Kemp Niver 46:12

Eliminated the red coat.

James Wong Howe, ASC 46:13

Yeah. So, well, better make it over, something wrong with that film or something. Nobody knew, you see.

Kemp Niver 47:03

Sound came in. And you say that you didn't have to get into a booth like some of the cameramen did?

James Wong Howe, ASC 47:14

No, they had done away with a booth.

Kemp Niver 47:19

This business of two years of being out of work, they got blimps by the time you got back.

James Wong Howe, ASC 47:23

We had a big blimp, some big blimp. They're big ones. But the microphone you know, it's a problem. That was the one that always got in the way. By lighting from top down a little, say, about 45 degrees or something like that.

Kemp Niver 47:43

You have a boom in the...

James Wong Howe, ASC 47:45

Yeah. But I tell you, that picture that one I made, we were just talking about...

Kemp Niver 47:53

Transatlantic?

James Wong Howe, ASC 47:53

Transatlantic. I had the art director put ceilings in all the cabins you know, on the boat. I had to really light from the floor, see? And keeping the light lower, that helped to eliminate the mic shadows.

Kemp Niver 48:13

Well, you could also hide the mic a little bit better too, cause you get a fixture...

James Wong Howe, ASC 48:18

And then we had a very good mixer and he helped out a great deal...

Kemp Niver 48:24

Wasn't that rather unique? Putting ceilings in on purpose?

James Wong Howe, ASC 48:31

Yeah, you know why? Because that would... It forced me to light a little different.

Kemp Niver 48:36

It would. I mean, after all, you've learned to put a key light above the point of the lens.

James Wong Howe, ASC 48:42

Well even so you know, Kemp, when you walk into a studio and you see a living room, a bathroom, no matter what kind of a room, you know, a log cabin, anything a bar, funeral parlor, could be anything. There's no ceiling and the minute you see this catwalk up there, it's loaded with lights.

Kemp Niver 49:00

Sure.

James Wong Howe, ASC 49:01

And the first thing you know, you walk in, everything becomes a habit. Man, I hit that one down here and hit this one across a wall. Put this one with the snoot on it and put on his face. Put this one back here for a backlight and hit that chair with this one. Well, what happens? We'd be getting lights coming from places...

Kemp Niver 49:21

You really don't belong. In other words, you you've got a source of light, literally. Now that thing that you did with Burt Lancaster...

James Wong Howe, ASC 49:30

Sweet Smell of Success

Kemp Niver 49:31

The Sweet Smell of Success. Boy, that was a heck of a job, just walking in and out of light and darkness all the way. Very, very interesting. I've heard a lot of professional cameramen — maybe they wouldn't tell you this, but I think they would — but in discussion, a lot of professional cameraman have a lot of respect for that particular thing. Of course., it takes a man that's been in the business a long enough time to get away with it. A lot of people couldn't get away with a job like that.

James Wong Howe, ASC 50:00

I don't think it's a matter of getting away with anything. Let's face it, I think photography, whether it's motion pictures or still, it's an art form. It's recognized now. Now we take an artist and he paints. Well, takes you many years... he starts before he knows a technique, and he learns it so well that he doesn't pay much attention to the technical end of it anymore. Now he's got such a knowledge... a feeling for it, he paints the way he feels... the way sees. His eyes see things that the usually another person or the man on the street, they don't see the same thing. They see it differently. They see color into something where one without the trained eye would never see it. And so they start to paint these things in. When they get finished, they got a beautiful picture — freedom in it, the lines, composition and expression what the artist is trying to say. Well, artists paint with a brush and color. A photographer, he has the medium of lights to film, to paint. So we have to learn then our technique. Now we say take for granted now, the cameraman knows his technique. Now what's he do next? Well, if he's a mechanical photographer, he sticks with a technique, he's going to use that meter, he depends on that meter. He says I want 200-foot key light. And I want my fill light to be 150 or 100, two-to-one, or whatever it is. And from that way you photograph every scene exactly that way.

Kemp Niver 52:03

Stereotyped.

James Wong Howe, ASC 52:04

Now what comes out? It comes out just like mechanical piece of photography. It has no feeling nor whatever. You don't know what the photographer or the cameraman is trying to say with his photography, with his lights, with his camera, and his lenses. It's just a nice photograph. Technically, it's fine. Perfect. You see. Now, I might think that photographer when he's really fulfilled, he's grown. He knows his technique, but...

Kemp Niver 52:43

He should add something to it.

James Wong Howe, ASC 52:44

He should add something... his expression, the way he sees it, the way he feels towards the subject matter, the character, the set, whatever the story is about. Well, we cameraman on the motion-picture business, we're always telling a story, photographing a story. We got to know what the story means. If it's gangster picture, one thing, if it's a musical comedy, it's another. In the picture, each sequence, they have different sequences. This sequence means that. It's early morning, this was late in the evening, this was noon. Now we got to light these things accordingly. Now, I would say that the average audience, they can't tell why, but when they see something that's right, that's true, and they believe it, they appreciate it. So my concern is will the audience believe this? Can I... I want to make it so that they believe it photographically. I'm not... Technically I know that they'll come in and do I really want technical perfection, or do I want really dramatized photography that expresses something? I don't believe in making all my photography absolutely perfect, technically. I like to see the rough edges here and there. I don't want to make it so perfect. That polish so high polish that I lose all the values. You see what I mean?

Kemp Niver 54:27

I certainly do.

James Wong Howe, ASC 54:28

I like little accidental things here and there. A little overexposed here. If I'm shooting the indoors, I want... and with hot sunlight outdoors, just like you see in Hud. That outside is really burning hot. Now, the inside is in halftones – somebody's in a deep shadow, but you'll feel cool inside. In the relationship. Everything is relative. If we have white and the dark, and I believe in it using dark areas and halftone areas, but it's a matter of placement, a matter of composition. They used to say, Well, I'm a low-key... they called me Low-key Howe. It's not because low-key... A lot of people misinterpret low-key... the meaning, and using a very low footcandle. Lighting very little illumination and weak illumination and it's diffused. And say, using 50 footcandle, rather than 150 footcandle, they think using 50 footcandle is low-key. That's not low-key. Low-key is something of a balance of dark areas against light areas. Because we need light to get an exposure. If we use such a low footcandle 25 or 30, then it's going to look gray. The picture will not have any strength, and if you're gonna make melodrama, you know you got to have strength. And the only way you get strength, is to have good deep shadows and good, clean, white, highlights. See, and that will give you strength. Like an artist, if he's going to paint a rock, he will use bold strokes. Now if he wants to paint a willow tree, use another kind of a stroke. A little lighter. Well, how does an artist, a photographer light this? You light it a little more diffused. So I think...

Kemp Niver 56:40

What did you find out? When did you find out that you were learning these kinds of things?

James Wong Howe, ASC 56:45

Well, learning I'm still learning every day I began now, I began to think I know something about photography after all these years, Kemp.

Kemp Niver 56:54

After 40 years.

James Wong Howe, ASC 56:55

That's but but I began to begin to learn to see things. When I'm on the street at different time of day or anytime or weather, I'm looking at things, I'm looking at shape, form, light on... the play of light. And I gotta study the light, the intensity of light. Because that's what we have to work with the cameraman, is light. It doesn't matter what kind of light, long as — if you can do color, because you have to have a certain Kelvin, you know — but if black and white, heck you can take to any kind of light. You can take a lantern, as long as its enough to get an exposure.

Kemp Niver 57:38

True.

James Wong Howe, ASC 57:38

And with fast film today you can we can get more realistic. Now, the thing that... when I say realistic is the way that things actually should look. And if it should actually look that way the light should come from these different sources where it shouldn't be always spotlighted. You take most of the pictures you see, with all these spotlights coming down, a man walks down the floor you see eight and nine shadows walking around. Well, you know daytime shot, it was day the light only comes from a window or open door. Inside, there's no spotlights coming from... In a nightclub, yes, you can have different sources because the light's from all over. It all depends. You see. You light a nightclub quite different than you would here sitting in this house. And, after all, the story, you see the subject the story is... We're all subservient to the story.

Kemp Niver 58:46

That's right.

James Wong Howe, ASC 58:47

Now, now, being a cameraman, knowing the technique, you know, I can take lights and light anywhere I want to use all the cucoloris to decorate the wall and... but what for? Is it right for this story? After making so many pictures, I don't like to repeat the same things over in the lighting. I've seen things been done. You know and after 47 years where you begin to say, Well, wait a minute. And that's when you really start working, because you... The person like myself had become very self-critical of my work. There are very few pictures I make today that I'm real happy with. Now, I like Hud, you see, but I've made some... I wish I could do it over again. I see the mistakes. Well, I began to feel a little free now with my work, with the lighting and the camera. A cameraman... people don't realize it, but they're they have an executive position. They've got lots of things to deal with. Electrician, props, and grips, hairdressers...

Kemp Niver 1:00:06

Makeup and mealtime.

James Wong Howe, ASC 1:00:08

Yeah.

Kemp Niver 1:00:09

Meal penalties.

James Wong Howe, ASC 1:00:10

You still got to get out a good-looking picture. Well, I think there's a more challenge today, Kemp, now, photographically speaking, and all the way down in making a movie because the audience are not the average 12, 13-year old mind as they used to say. The television and radio... these kids are very bright today, you know? And you can't fool them — they want to see your real stuff. And they're after knowledge, and you can't kid them. They're way ahead of us. So, I think all the way down, not just photography, I mean to say from storylines, acting-wise, directing-wise, sets and everything else. And we mustn't take it for granted.

Transcribed by https://otter.ai

American Cinematographer interviews cinematographers, directors and other filmmakers to take you behind the scenes on major studio movies, independent films and popular television series.

Subscribe on iTunes