A New Millennium of Screen Artistry

AC enters a new era of cinematography and production coverage in the 2000s.

AC enters a new era of cinematography and production coverage in the 2000s.

As the 21st century progressed through its first decade, American Cinematographer tracked a number of prevailing trends that would eventually become cornerstones in a new foundation for motion imaging.

The most significant of these developments was the continued adoption of digital technology in the realm of cinematography and postproduction. Digital video, formerly scorned as a medium aesthetically inferior to film, began to gain a firmer foothold as a viable format. While debates continued to rage over the quality of DV cameras, and some disputed the cost savings cited by budget-minded producers, higher-definition video proved here to stay.

One of the earliest adopters of DV for a feature narrative was Windhorse, which premiered at the 1998 Santa Barbara Film Festival, where it won the award for Best U.S. Independent Film and made director Paul Wagner the co-winner of the Best Director award. The movie’s cinematographer, Steve Schecter, shot the film on two Sony cameras: a professional DigiBeta DVW-700WS and a prosumer DV DCR-VX1000 (seen above). Also during that period, other prominent cinematographers became early pioneers, including Anthony Dod Mantle, ASC, BSC, DFF (The Celebration), Jim Denault, ASC (The Book of Life), Ellen Kuras, ASC (Bamboozled), Robby Müller, NSC, BVK (Dancer in the Dark) and Roberto Schaefer, ASC, AIC (Everything Put Together).

In the first years of the “aughts,” AC covered many early examples of features shot primarily on digital video, including The Idiots, directed by Lars von Trier and shot by von Trier, Casper Holm, Jesper Jargil and Kristoffer Nyholm (AC Jan. ’00); Timecode, an experimental project that director Mike Figgis, director of photography Patrick Alexander Stewart and operators James O’Keeffe and Tony Cucchiari shot live with four DV cameras running simultaneously (April ’00); Third World Cop, a Jamaica-set crime thriller shot by Richard Lannaman (April ’00); Chuck & Buck, shot by Chuy Chávez (July ’00); The Anniversary Party, photographed by John Bailey, ASC (July ’01); Killing Time, shot by Joe Foley (Feb. ’02); Personal Velocity, shot by Ellen Kuras, ASC (April ’02); Hotel, another Figgis project presented in multiple onscreen images (April ’02); 24 Hour Party People, shot by Müller (July ’02); and Interview With the Assassin, shot by future ASC member Richard Rutkowski (Dec. ’02).

Kuras proved definitively that standout cinematography was possible on digital video by earning the Sundance Film Festival’s Excellence in Cinematography Award and an Independent Spirit Award nomination for her outstanding work on Rebecca Miller’s Personal Velocity, which also won the Grand Jury Prize at Sundance. The project’s format was predetermined by its financier, InDigEnt, a company whose mandate was to finance low-budget projects made with digital media. In her interview with then-AC senior editor Rachael K. Bosley, however, Kuras maintained that she was “not a fan of DV,” noting that on an indie budget, “shooting in Super 16 and blowing it up [to 35mm] offers much better quality and control.” Nevertheless, she ultimately selected two Sony DSR-PD150 PAL cameras and made the bold creative choice to shoot Personal Velocity in widescreen 16:9 — a decision she described as “a bit rebellious.”

Kuras also sought to manage Miller’s expectations. “She was used to shooting on 35mm, and I told her she’d have to temper her expectations with what digital video can do. On the first day of our scout, for example, we went to a location where we were just going to shoot a couple of pickups, and I could see that the direction we have to shoot in would be bright, sunny, front light, and I simply said no. The cameras have a really hard time handling great contrast — you have to be extra careful about where and when you shoot, or the image just falls apart.”

Of course, digital cameras have come a long way since those days, and can now be employed without the same reservations.

Kuras also pointed to another of the era’s major developments by noting that “on digital projects in particular, it’s important to lay the groundwork when you shoot, work with a good colorist, and oversee postproduction prior to the film’s release.”

Her counsel seems especially prescient given the rise of the digital intermediate, which was first employed for an entire motion picture on Pleasantville, shot by John Lindley, ASC (AC Nov. ’98), but is now a standard, intricate, and very creative step in the postproduction process, which has firmly established the colorist — the modern color timer — as a significant collaborator for the cinematographer.

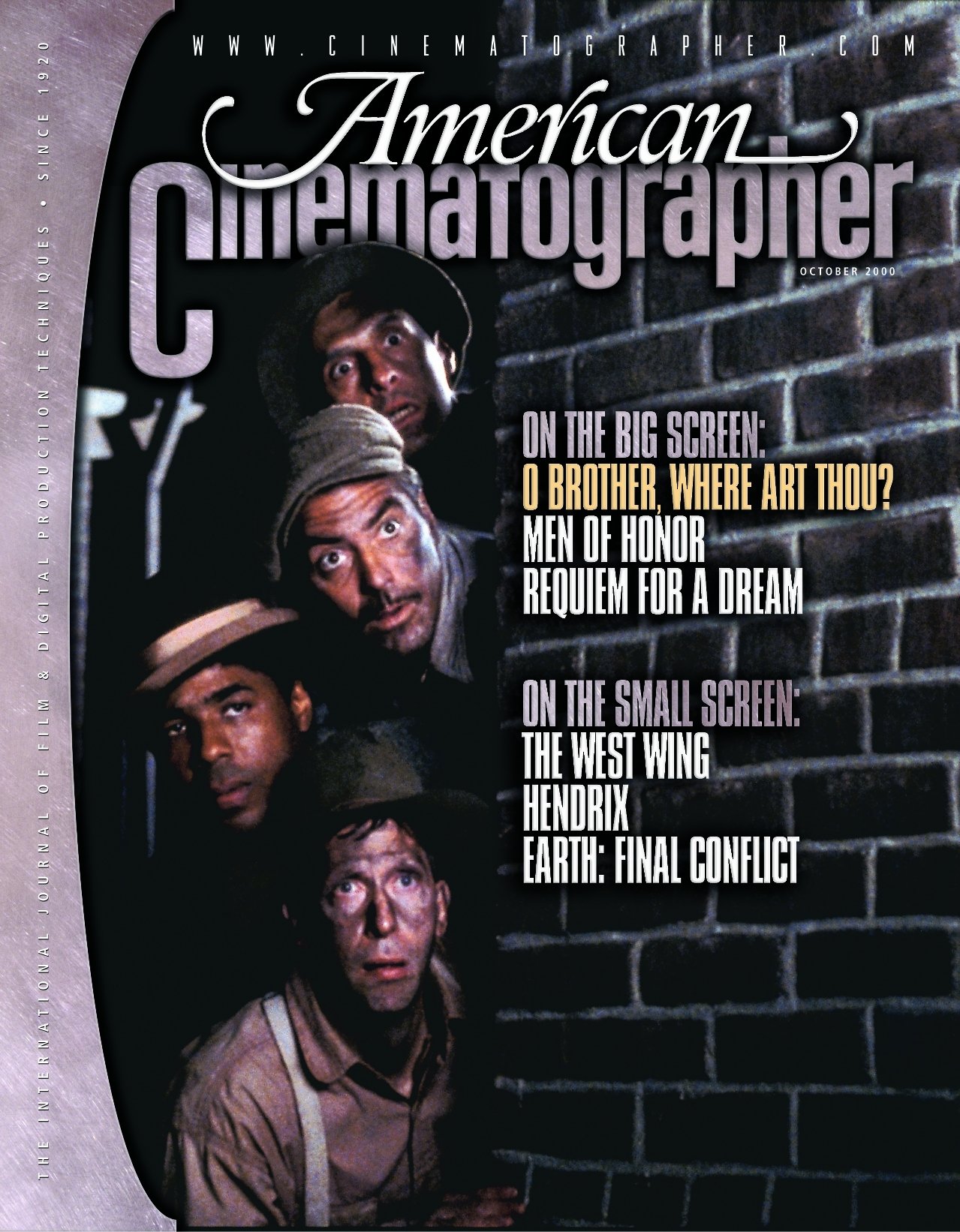

Another notable case study of the DI process was the Coen brothers’ O Brother, Where Art Thou?, shot by Roger Deakins, ASC, BSC. In the October 2000 article “Escaping From Chains,” by Bob Fisher, AC took a close look at the workflow Deakins adopted. The cinematographer spent about 10 weeks in a digital suite at Cinesite fine-tuning the film’s look after the negative was locked down and converted to digital format. “We found that the more we tried to manipulate the image, the more noise and electronic artifacts appeared, and then we would have to rescan and retime the image,” Deakins said. “In the end, we kept the manipulation to a minimum in order to maintain quality overall. We affected the greens and played with the overall saturation but little else. We only used windows, for instance, on a couple of shots.”

Sarah Priestnall, now an ASC associate, served as director of digital mastering for Cinesite. “[The process] was experimental in the sense that it was a learning process for all of us,” Priestnall said. “Most people are going to focus on the use of this technology because it is new, but I think the most important thing is that everyone learned that the process can be very creative and intuitive, [enabling] cinematographers to create looks that may not be possible or practical otherwise.”

Deakins cautioned, “The process is not a quick fix for bad lighting or poor photography; it is a tool to be used in the same way as any other tool.”

Throughout the 2000s, AC addressed other important elements of the “digital revolution.” In March 2001, the magazine published “Painting With (Virtual) Light,” an article by Stephanie Argy revealing how digital artists were lighting or enhancing scenes via computer. A few months later, senior European correspondent Benjamin Bergery interviewed George Lucas to elicit his thoughts on the new landscape (“Digital Cinema, By George,” Sept. ’01). “In the end, it doesn’t make any difference which medium you’re using — it’s all storytelling,” Lucas said. “I came to digital because of quality and ease of work, which is why I pushed Sony and Panavision to build digital cameras and lenses, and why I’ve been pushing Texas Instruments and the theaters to project digitally.”

Other important articles addressing digital technologies included several special reports on film archiving, restoration and preservation (including multiple articles in Nov. ’01 and follow-ups later in the decade); a comprehensive article on the history of cinematographers making creative use of postproduction techniques (“A Legacy of Invention,” May ’02); associate editor Douglas Bankston’s two-part examination of color space and its impact on image control (“The Color-Space Conundrum,” Jan. and April ’05); ASC member Richard Crudo’s proposal for more accurate and consistent methods of look management during film-to-digital dailies transfers (“A Call for Digital Printer Lights,” Sept. ’06); a recap of the 2009 Camera-Assessment Series, in which the ASC and the Producers Guild put seven digital cameras through their paces (“Testing Digital Cameras,” June ’09); and a report on previsualization detailing a collaborative assessment involving the ASC Technology Committee (now known as the Motion Imaging Technology Council, or MITC), the Art Directors Guild and the Visual Effects Society (June ’09).

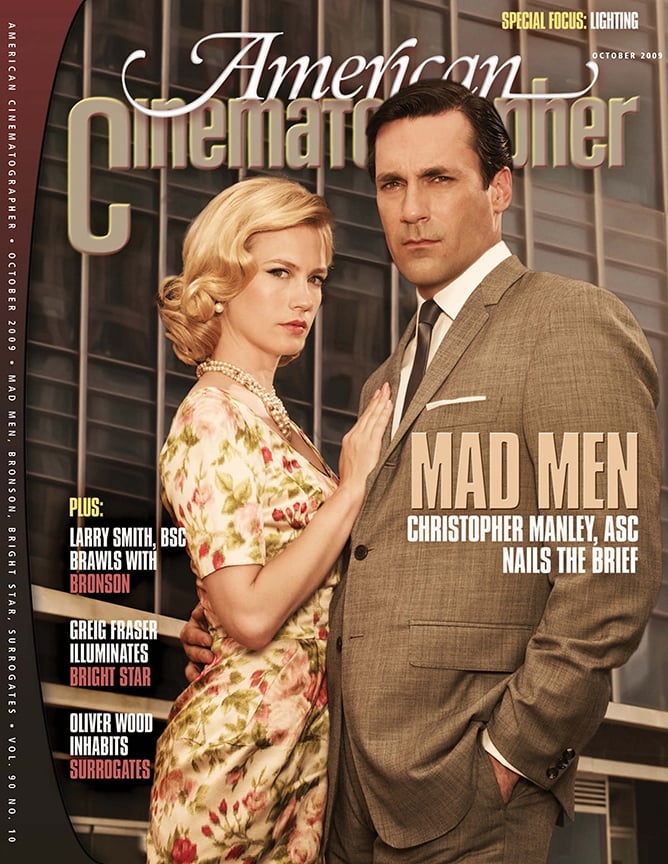

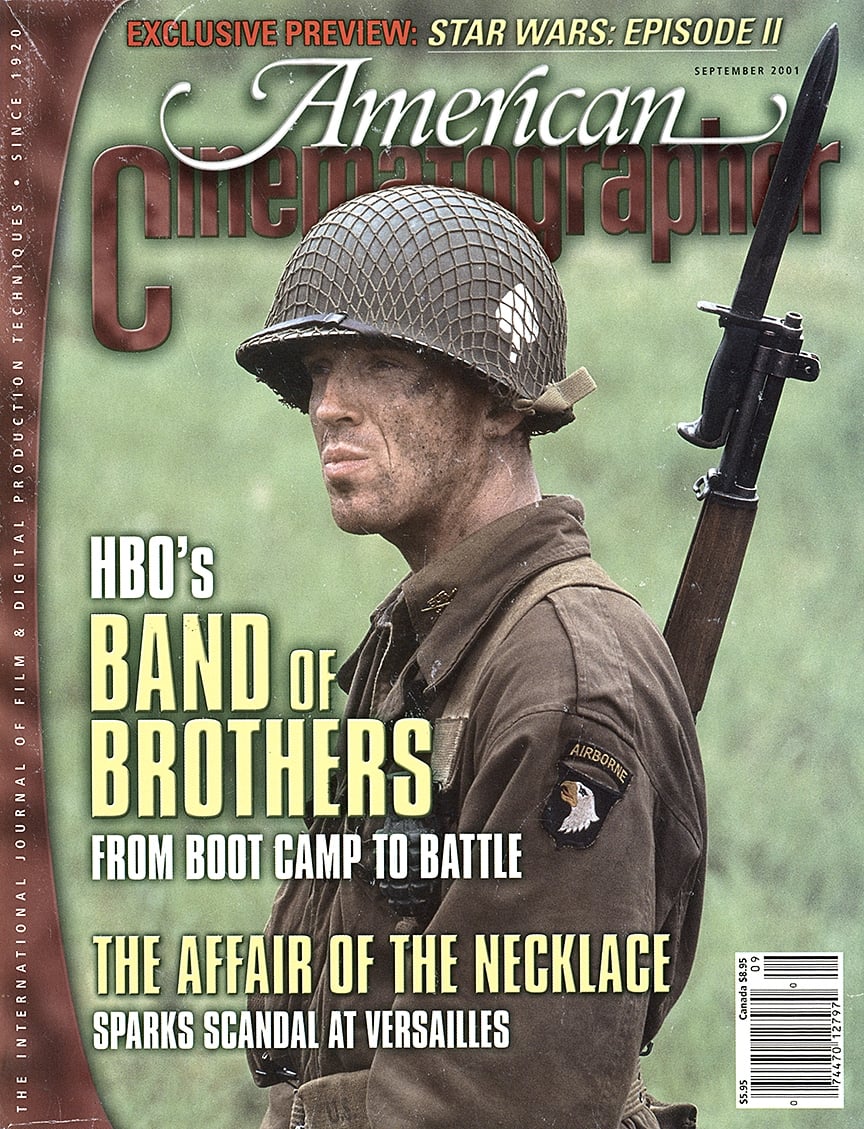

The 2000s were also notable as a second Golden Age of Television, which AC recognized with coverage of highly regarded productions such as The Sopranos, Sex and the City, Buffy the Vampire Slayer, The West Wing, The X-Files, C.S.I.: Crime Scene Investigation, Lost, Six Feet Under, Band of Brothers, Angels in America, The Wire, 24, Battlestar Galactica, Entourage, Rome, Grey’s Anatomy, Smallville, 30 Rock, Desperate Housewives, Mad Men, Dexter and True Blood, among others.

Speaking about his experience shooting Mad Men, one of the most acclaimed shows of the decade (“Pitch Perfect,” Oct. ’09), cinematographer Chris Manley, ASC told AC, “There’s a virtue to sticking with one show for a while, which is that you go into the specific problems of the photography really deeply, and you learn — you have to. It’s surprising, the things I’m still learning on this show.”

Manley shot 71 episodes of the show from 2008-2015, earning four Emmy nominations and two ASC Award nominations for the handsome period look he helped craft. “Shooting episodic television is a real marathon, and the schedule just kind of washes over you and becomes your life,” he told Bosley. “It’s very easy to get discouraged, but with Mad Men I don’t. This is the first time I’ve done two seasons of any show. I’ve done some good shows, but nothing this good. The quality of the writing is fantastic, and that keeps me excited about every episode. It’s rewarding to come to work and feel like I’m involved in creating great drama.”

Another television production that received universal acclaim was the 2001 HBO miniseries Band of Brothers, shot by Remi Adefarasin, BSC and Joel Ransom, CSC. The 10-part World War II epic was modeled after the realistic look that executive producer Steven Spielberg had created with cinematographer Janusz Kaminski for the 1998 feature Saving Private Ryan. “[They were after] that same kind of heightened contrast and lowered saturation,” Adefarasin confirmed in Jean Oppenheimer’s article “Close Combat” (Sept. ’01). “A much-used phrase was: ‘Like dropping a documentary unit into the past.’ That was the approach.”

Adefarasin says Episode 9 was his main motivation for working on the miniseries. “Not a single shot is fired, yet the whole horror of warfare is evident in that hour. [We see] how lives are destroyed, how hate breeds, and the futility of killing our fellow man, but we also see how people help each other. The episode is called ‘Why We Fight,’ and it’s the reason I signed up for Band of Brothers.”

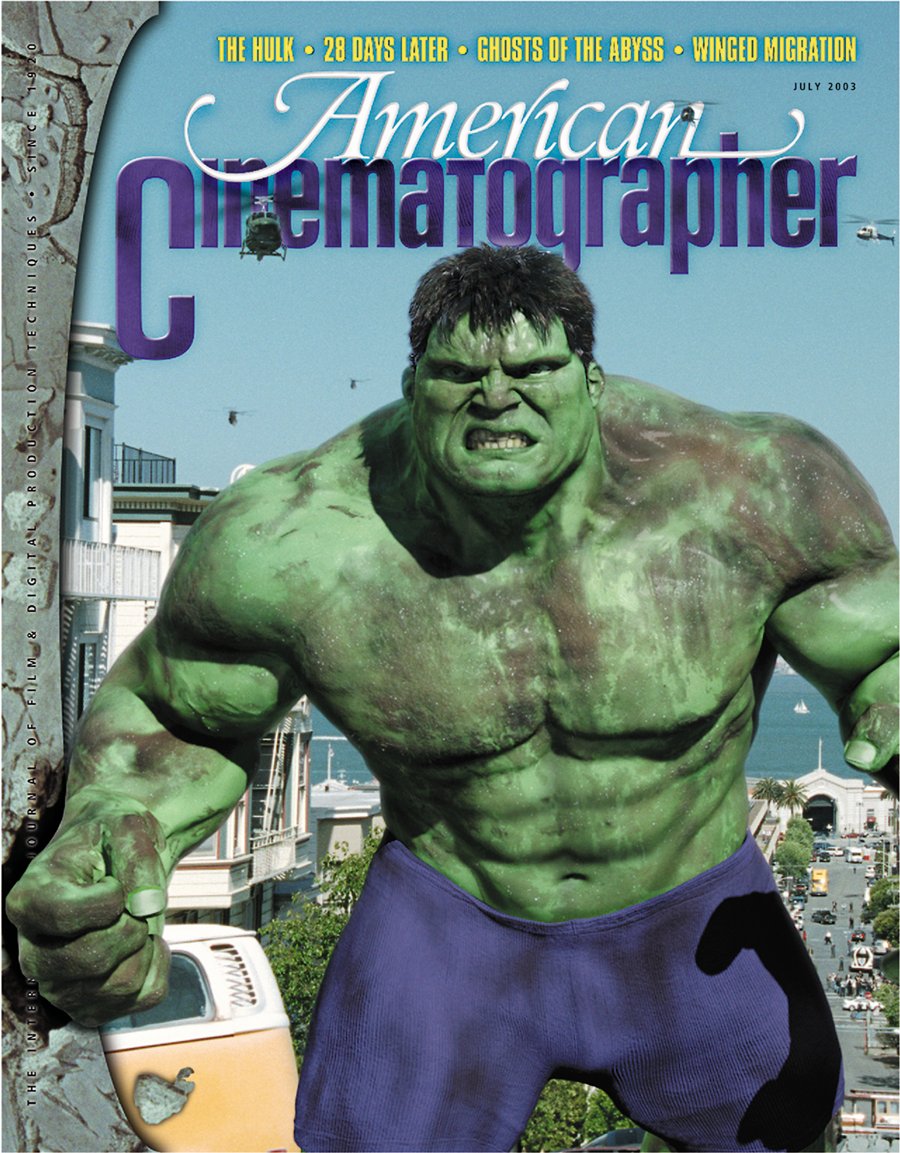

In the feature realm, the 2000s produced a series of visually ambitious superhero movies that led to an explosion of the genre in the decade that followed. Prominent directors were paired with renowned ASC members to make these movies as epic and eye-popping as possible. Major titles covered in AC included X-Men (July ’00) and X2: X-Men United (April ’03), directed by Bryan Singer and shot by Newton Thomas Sigel, ASC, followed a few years later by X-Men Origins: Wolverine, teaming Gavin Wood with Donald McAlpine, ASC, ACS (May ’09); Unbreakable (Dec. ’00), directed by M. Night Shyamalan and shot by Eduardo Serra, ASC, AFC; Spider-Man (June ’02), directed by Sam Raimi and shot by Don Burgess, ASC, and its two sequels (July ’04 and May ’07), which paired Raimi with Bill Pope; Hulk (July ’03), which drew Ang Lee and Frederick Elmes, ASC into the genre; Batman Begins (June ’05) and The Dark Knight (July ’08), the first two installments of Christopher Nolan’s Batman trilogy shot by Wally Pfister, ASC; Superman Returns (July ’06), another entry from Singer and Sigel; and Iron Man (May ’08), directed by Jon Favreau and shot by Matthew Libatique, ASC, which launched the Marvel Cinematic Universe in spectacular fashion.

Nolan set out to present a far edgier version of Gotham City’s famous crimefighter than audiences had ever seen on a big screen. Although Pfister conceded that he’d been a huge fan of the campy 1960s television series Batman in his youth (”My dad worked for ABC, and he used to come home with armfuls of Batman souvenirs”), he helped Nolan add darkness to the Dark Knight’s new iteration. “Chris wanted the film’s visuals to come from a very real place,” Pfister told AC in the article “Batman Takes Wing,” adding, “He felt the settings should reflect the psychological underpinnings of a dark character who’s driven by tragedy in his life. With that goal in mind, we tried to create a unique urban environment, something much different than what appears in the other Batman films.”

The cinematographer did reveal, however, that during prep Nolan and production designer Nathan Crowley reminded him of his own childhood as a Bat-fan: “The two of them had assembled all of these materials in Chris’ two-car garage. It was like a kid’s workshop in there — the walls were covered with research, and Nathan had been building models for a brand-new Batmobile from a toy car, airplane and rocket kits … Chris has a passion for every little detail, so from the beginning he was instrumental in every single design concept for the movie, from the bolts that hold the wheels on the Batmobile to the curves and lines of Batman’s cowl.”

The massive box-office success of Nolan’s vision set the stage for subsequent superhero films that explored the darker side of superhero life, but with Iron Man, Favreau — previously best known for helming the Christmas romp Elf and for his iconic acting turn as a mopey, lovelorn, recently-relocated-to-L.A. bachelor in the 1996 hipster comedy classic Swingers — harnessed the manic energy of star Robert Downey Jr. to imbue the movie with a wisecracking style of humor that became a hallmark of the Marvel Universe superhero films. AC paid a visit to the set depicting billionaire scientist Tony Stark’s office, within a massive garage that also housed Stark’s collection of exotic cars (some of which actually belonged to Favreau). There, we found Libatique fussing — for quite some time — with small accent lights he was using to add some stylish illumination to Stark’s work area. “This is an important movie for Marvel, and they’re giving us all the time we need on this show to get even the tiniest details just right,” Libatique said.

Indulging the filmmakers’ craftsmanship has clearly paid off for Marvel in the years since with a string of enormous blockbuster hits starring other heroes from the brand’s ever-popular comic books.

The 2000s launched many other careers into the stratosphere. A trio of ASC members who hail from Mexico — Emmanuel Lubezki, Guillermo Navarro and Rodrigo Prieto — had a particularly rewarding decade that cemented their reputations as visionary cinematographers.

During a mid-’90s lunch at the old Hamburger Hamlet on Hollywood Boulevard, ASC legend Conrad L. Hall touted Lubezki’s preternatural skill, advising your humble author to “keep an eye on that kid from Mexico — he’s the real deal.” Lubezki proved Hall prophetic in 1996, when he received both Academy and ASC Award nominations for his stunning work on the family fantasy film A Little Princess. Now known to all by his nickname, “Chivo,” Lubezki kept the momentum rolling with Academy and ASC Award nominations for his work on Tim Burton’s Sleepy Hollow, a production AC covered in December 1999 after visiting the show’s sets in England. His reputation for stunning work was cemented with the lyrical imagery he lent to Terrence Malick’s period drama The New World (Jan. ’06), followed by the gritty sci-fi film Children of Men (Dec ’06), which featured several jaw-dropping single-shot action sequences. Lubezki earned Academy Award nominations for both films, along with ASC and BAFTA Awards for the latter.

Prieto joined the fiesta in 2000 by earning a Silver Ariel Award at Mexico’s equivalent of the Academy Awards ceremony for his work on the acclaimed drama Amores Perros, following that honor with a 2003 ASC Award nomination for Frida; 2006 Academy, BAFTA and ASC Award nominations for Brokeback Mountain; and a 2007 BAFTA nomination for Babel. Discussing his collaboration with director Ang Lee on Brokeback Mountain in the Jan. 2006 issue of AC, Prieto said, “When I read [the script], I knew I had to participate in it. This is the 21st century, and there’s still quite a bit of intolerance toward homosexuality. This script really makes you feel empathy for these characters.” He added, “I only hope the cinematography helps tell this story of deep human emotions that touch everyone, regardless of nationality, religion, politics or sexual orientation.”

Not to be outdone, Navarro — who had risen to prominence in the 1990s with his stellar work on Desperado, From Dusk Till Dawn, Jackie Brown and other films, hit a new peak in 2006 when he teamed with Guillermo del Toro on the fantasy-infused Spanish World War II drama Pan’s Labyrinth, which earned Navarro an Academy Award for Best Cinematography.

Other ASC members also made a lasting mark on cinema history during the 2000s, and their achievements were duly noted and explored with comprehensive coverage in AC. These renowned cinematographers were led by Roger Deakins, who collected five Academy Award nominations during the decade for the imagery he brought to O Brother, Where Art Thou?; The Man Who Wasn’t There; No Country for Old Men; The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford; and The Reader (on which he shared director of photography duties with Chris Menges, ASC, BSC). Deakins also won an ASC Award for The Man Who Wasn’t There and collected five more ASC nominations, including one for Revolutionary Road.

Additional ASC members who made multiple trips down red carpets included Dion Beebe (Academy and ASC Awards for Memoirs of a Geisha, along with an Oscar nomination for Chicago and an ASC nomination for Collateral), Bruno Delbonnel (an ASC Award for A Very Long Engagement, Academy and ASC nominations for Amélie, and an Oscar nomination for Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince), Caleb Deschanel (an ASC Award and an Oscar nomination for The Patriot, plus Academy and ASC nominations for The Passion of the Christ), Robert Elswit (Academy and ASC Awards for There Will Be Blood, and nominations from both organizations for Good Night, and Good Luck), Lubezki (Academy nominations for The New World and Children of Men, along with an ASC nod for the latter), and Pfister (Academy and ASC nominations for Batman Begins and The Dark Knight, and an Oscar nomination for The Prestige).

Additional research by Richard Crudo, ASC.

Subscribe to American Cinematographer for access to the complete AC Archive — all 100 years of the magazine’s coverage, including every story referenced in this article.

Check here for more decade-by-decade breakdowns of AC’s 100 years.