Adding Spice to Flamin’ Hot

Cinematographer Federico Cantini, ADF and director Eva Longoria blaze through period settings and manufacture the perfect shade of red to tell a story of snack-food innovation.

By Sarah Fensom

All unit stills and frame captures courtesy of Searchlight Pictures

Flamin’ Hot isn’t really about spicy Cheetos. “Nobody wants to see that movie,” director Eva Longoria says with a laugh. Instead, the film’s focus is Richard Montañez — a Mexican-American executive who started as a janitor at a California Frito-Lay factory, eventually helping the company develop its wildly popular spicy snacks and target an untapped Latino market. For Longoria, who makes her directorial debut with Flamin’ Hot, it was important to tell a story that transcended the rags-to-riches trope. “I didn’t want viewers to receive it like medicine,” she says. “I wanted to hit the systemic oppression that is built into corporate America, and our society and communities — and I wanted to show how we persevere and succeed in spite of these factors.”

The cinematographer who would help realize this vision was ASC Master Class alum Federico Cantini, ADF.

Cool and Classic

To dramatize Richard’s story, Longoria decided it had to be filtered through his point of view and narrated in his voice — a mix of honesty, humor and resourcefulness. Drawing inspiration from the voice-over-driven narratives of directors Adam McKay and Martin Scorsese, Longoria sought to create a tone that would carry viewers through Richard’s story briskly, while supplying crucial information — particularly about the Latin-American experience. “I wanted it to move like a page-turner, with the music pushing you into the next scene and the camera movements whip-panning you into the next scene,” she says.

When Longoria brought Cantini aboard the project, the filmmakers discovered that they had nearly identical visions for the film, down to exact references: “It’s like we shared a brain, creatively,” she says. Cantini describes their approach as “cool, but classic” — a fun, fast pace that aspires to the cadence of Scorsese and Spielberg. “We planned to have a lot of oners, but we never wanted to favor a cool shot over the story,” the cinematographer says. Ultimately, the watchword was “authenticity.” Adds Cantini, “We discussed a ton of possible shots and ideas, and Eva always said, ‘If it works for the story, we do it — if it doesn’t work for the story, we don’t.’”

Shooting at a Fast Clip

For the duration of the eight-week shoot in Albuquerque, N.M., Cantini chose to shoot with the Sony Venice, due to its versatility in multiple areas. “We wanted to do anamorphic, Super 35 and large format, and all of that at 4K, so it was ideal,” the cinematographer says. “We also have some slow motion and some shots with the Laowa 24mm T14 2x PeriProbe lens — a lens that needs a lot of light — and the Sony Venice has a dual ISO, so you can use 500 or 2,500.” He adds that with the camera’s Rialto extension, it was “easy to go handheld, and it’s good for Steadicam. It’s good for whatever! And we always shot with two cameras — or sometimes three — because Eva likes to go fast, and I’m the same.”

Moving With the Times

During preproduction, one of the first things Cantini did was break the script into decades. Flamin’ Hot follows Richard (Jesse Garcia) during his childhood at a Guasti, Calif. work camp in the 1960s and his turbulent years hustling on the streets of East Los Angeles in the 1970s, and then through his tenure at the Rancho Cucamonga Frito-Lay factory in the 1980s and ’90s. Cantini and Longoria wanted distinct camera languages that felt appropriate for the respective time periods and for Richard’s narrative trajectory. With the help of ASC associate member Guy McVicker, Panavision Woodland Hills’ director of technical marketing, and marketing executive Rik DeLisle, along with local support at Panavision Albuquerque, Cantini put together three different lens series. The cinematographer also worked closely with Walter Volpatto, senior colorist at Company 3, to design specific LUTs for each lens — inspired by film stocks available during the eras they were to represent.

To capture the childhood of young Richard (Carlos S. Sanchez) in the ’60s, the cinematographer used JDC Xtal Xpres anamorphic lenses, which Cantini describes as “the stuff that dreams are made of — with gorgeous peripheral shading, creamy definition and diffused highlights that immediately evoke old childhood memories.”

Richard’s early years were difficult — he worked hard picking grapes with his family and was bullied at school — but there were also bright spots: We see him playing among the idyllic vineyards and bonding over homemade burritos at lunch with young Judy (Jayde Martinez), a friend who eventually becomes his wife. “Everything comes back to how Richard tells the story,” Cantini says. “Richard’s childhood was tough, but he remembers it as a happy time, so we have to show it that way. For example, there is a crane shot that starts very wide and high, and you see the beautiful field at the vineyard. The camera moves down and Richard is smiling and running toward it. Then he turns, the camera pans, you see his dad, and his dad slaps him and says, ‘Get back to work.’ You see his whole emotional transformation in one long shot, which is something we did many times in the film.”

During the ’70s, Richard became involved with gangs, and Cantini wanted to express the turbulence of those times. “Those are the only moments when we have handheld camera; in the rest of the film, it’s all dolly moves and Steadicam by A-camera operator Dennis Noyes,” Cantini says. For these fast-paced sequences, which include both Richard and Judy (Annie Gonzalez) running from law enforcement, Cantini notes, “We had the high, summer-noon sunlight in our favor, and used it to create a harsher look. But with our Canon K-35 lenses, we were able to keep rich shadows and intense contrast.”

In the ’80s, Richard learns that he and Judy are going to have a family and straightens out his act. Cantini continued to use the K-35s when shooting Richard in his house during this period, as the protagonist struggles to find direction. But for scenes that take place after Richard begins working at the Frito-Lay factory, the cinematographer notes that he switched to “Panavision Panaspeed large-format lenses that were customized specifically for the movie — to replicate the Panavision Super Speed look of that era, but keep the bigger-than-life effect of the large format.” Cantini also toggled between two Panavision Primo zooms — an 11:1 SLZ11 29-327mm T3.1 (a 25-275mm with 1.18x expander) and a 4:1 SLZ 17.5-75mm T2.3 — with the same modified look. “After Richard gets the job in the factory, he has more space to breathe — so, we switch to the large format to make everything look a bit bigger, brighter and wider,” Cantini says. “The camera also starts moving faster and forward all the time, as if the energy of the factory is following Richard.”

Factory Filming

Quite a lot of Flamin’ Hot takes place in the Frito-Lay factory (really, the old Albuquerque Journal building, a space with ’80s-period details and a semi-functional production plant). There, we see Richard’s day-to-day duties as a janitor, but also his developing bonds with co-workers — like Clarence (Dennis Haysbert, below), a machine manager who shows Richard the ropes — as well as a handful of powerful speeches and revelations, and Cantini sets up a shot with director Eva Longoria. a lot of Cheetos getting made.

How to make the factory visually dynamic was a considerable challenge for the filmmakers. “I think we watched all the factory movies that exist in the world,” Cantini says with a laugh. Longoria recalls drawing from numerous influences, including Martin Ritt’s 1979 feature Norma Rae (shot by John A. Alonzo, ASC) and Mike Judge’s 2009 comedy Extract (shot by Tim Suhrstedt, ASC). Another key reference point, Longoria adds, was the 2017 journalism thriller The Post (shot by Janusz Kamiński) — specifically, “how Spielberg shot the newspaper factory with such urgency.”

Cantini says that all camera movement inside the factory was planned with precision in mind. The filmmakers also used the large space to play with elements like scale: When we first see Richard in the factory, he’s very small in the frame. “It’s to show this place is bigger than him — and we put others in the foreground to make him feel small,” Longoria notes. At one point, the film jumps about 10 years into Richard’s tenure at the factory. He’s still a janitor at that time, but he’s grown in confidence, “so he’s the one that’s the biggest in the composition,” the director says. “Like the opening shot of John Travolta in Saturday Night Fever, he’s literally pushing the camera back and there’s something powerful about that.”

For the lighting, a delicate balance had to be established: Richard’s workplace had to feel authentically like a factory, but the filmmakers didn’t want it to be devoid of character. “I told Fede, ‘It cannot feel concrete and gray. There needs to be joy in this factory!’” Longoria says.

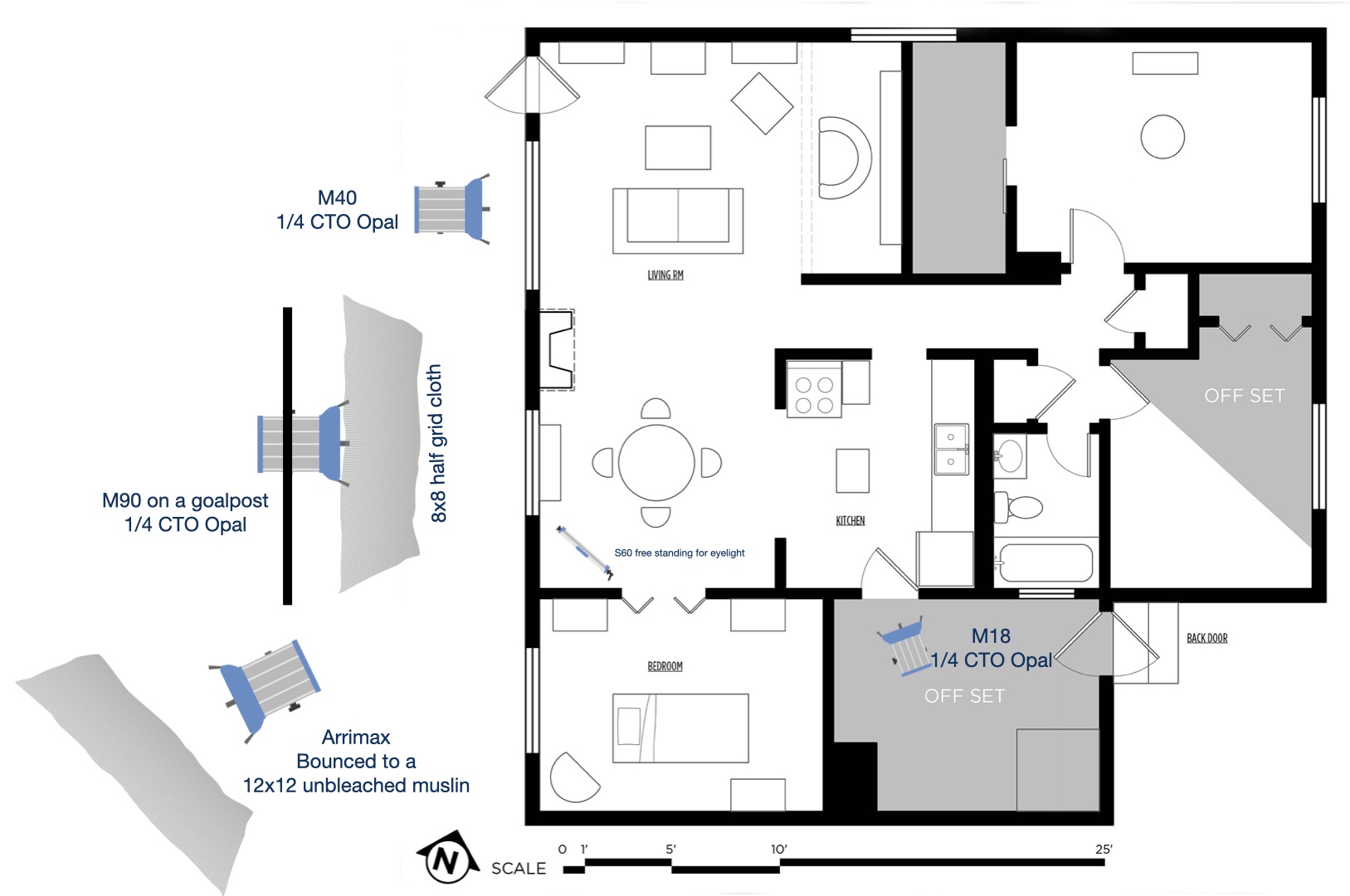

To achieve this desired look, the filmmakers took care to avoid lighting exclusively from overhead, balanced the duller tones in the space with more attractive silvers and blues, and made thousands of tube changes. “Gaffer Neil Solberg replaced 2,500 fluorescent tubes with 5,600K corrected tubes for all the ceiling light,” Cantini says. “Then, for the practicals, he added 3,200K tubes with Rosco 5336 Aztec Gold gel on them to all the surrounding walls.” On the factory floor, the cinematographer had three 12'x12' solid negatives moving around to control the contrast of the tubes. Key grip Rudy Covarrubias made individual overhead diffusers — with magnets attached — for the factory fixtures, allowing any given fixture to be quickly diffused above the actors. For the key lights on the actors, Cantini used two Arri SkyPanel S360s that were diffused through a 12'x12' ¼ Grid Cloth, with four 8'x4' floppies that acted as baffles to keep the rig controlled. He put lights outside the windows of the factory, too. “We had two Arrimax 18Ks on a 90-foot condor with ¼ CTO on each one,” Cantini says.

Seeing Red

In a scene that drives another significant shift in the film’s look, Richard and Judy, who have been attempting to develop a spicy Cheeto from scratch, have their son (Brice Gonzalez) taste what ends up being the corn puff done just right. As the boy holds up the Cheeto, we catch a brief glimpse of bright-red color for the first time in the film. As Cantini explains, the light comes through the window of the family’s home — courtesy of an Arri M90 with ¼ CTO and Opal, through an 8'x8' frame of 1/2 Grid Cloth — “and touches the Cheeto in a way that makes it pop.”

Soon after, the first bag of Flamin’ Hot Cheetos comes down the production line at the Frito-Lay factory, and suddenly the signature red color is spangled all across the screen. “It’s like Richard’s family, symbolized by a warmer palette, whooshes into the factory.”

It took careful preparation to ensure the Hot-Cheeto-red made a big impact when the time was right. Longoria made certain nothing in the film — “not an extra, not a car, not a flag deep in the background” — featured red, or even orange, until after the initial reveal of the new snack. Cantini notes that the blue walls and cool, silver tones of the factory set up the ideal contrast for the bright-red hue, as well. The filmmakers went through a rigorous process of camera tests to select the perfect color for the Cheetos. “We tested real Flamin’ Hots, we played with filters, we played with different colors — and what we landed on is definitely a manipulation, because we needed it to pop that first time in the factory,” Longoria says.

Even though Flamin’ Hot addresses a number of complex social issues, the story wouldn’t be complete without a little Cheeto dust. “Everybody knows the thing about Cheetos is the red fingers — we had to do something with that,” Longoria says. She decided that Roger Enrico (Tony Shalhoub), the CEO of PepsiCo who agrees to try Richard’s concoction and hear out his ideas, should be the character in the film with the red-stained fingers. Cantini used a split diopter to capture both Enrico’s mouth tasting Flamin’ Hot Cheetos for the first time and the bright red dust on his fingertips. “It was this way to humanize Enrico,” Longoria says. “Even someone like him gets Cheeto dust on his fingers. It’s completely universal.”

A Game-Changing Master Class

Flamin’ Hot cinematographer Federico Cantini, ADF attended an ASC Master Class session in 2016, just a few years after he relocated to Los Angeles from his native Buenos Aires. The five-day program leads rising cinematographers through a series of seminars and classes taught by top professionals in the field. For Cantini, the Master Class wasn’t just an opportunity to learn new techniques — it became a major turning point in his career. “It was a game changer. Besides all the classes and presentations, I was able to start a network and spend time with these great cinematographers,” he says.

Among others, he met cinematographer Julio Macat, ASC, a fellow Argentine. Cantini had been working mostly in commercials, and it was through Macat’s recommendation that he was hired as director of photography on his first feature, the 2020 comedic drama Give or Take. Cantini met a producer on that project who called him for Unplugging — a film starring Eva Longoria — and soon after that film wrapped, Longoria got in touch with him about Flamin’ Hot. “It’s really hard to get your first gig,” Cantini says. “My career here in the U.S. started because of the ASC Master Class.”

Tech Specs:

- 2.39:1

- Cameras: Sony Venice

- Lenses: Panavision Panaspeed, Primo zoom; JDC Xtal Xpres; Canon K-35; Laowa PeriProbe