Jeff Cronenweth, ASC: An Adventurous Eye

The cinematographer’s career exemplifies how talent, versatility, opportunity and collaboration can combine to result in bold camerawork.

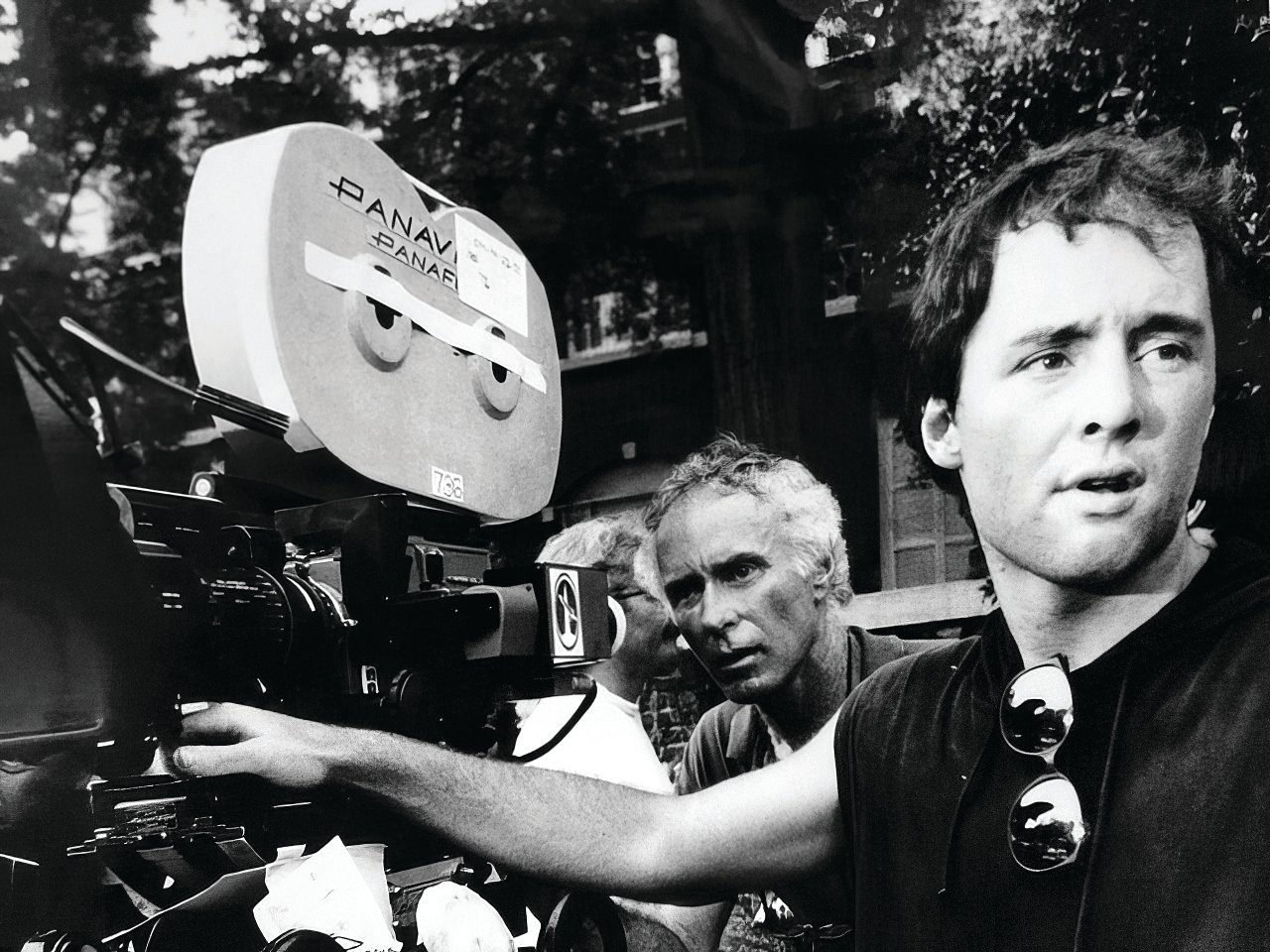

Directors who have worked with Jeff Cronenweth, ASC observe that he is quiet, centered, and possesses a very dry sense of humor. Working in an eclectic mix of genres and styles, he quickly zeroes in on central concepts, often exceeding expectations with the results. His career as a feature cinematographer began auspiciously with David Fincher’s eye-popping Fight Club (AC Nov. ’99), and his filmography since then includes The Social Network (AC Oct. ’10), Gone Girl (AC Nov. ’14), One Hour Photo (AC Aug. ’02) and the Amazon miniseries Tales From the Loop (AC April ’20). Cronenweth has also shot stylistically bold, groundbreaking music videos for David Bowie, Taylor Swift, Janet Jackson, Nine Inch Nails and many other top artists.

It wouldn’t be at all hyperbolic to say Cronenweth was born into filmmaking. His great-grandfather owned and operated a photographic-equipment store in Wilkinsburg, Pa.; his grandfather Edward worked as a portrait photographer for Hollywood studios during the peak of that unique specialty, earning an Academy Award for his work; his grandmother Rosita was a Busby Berkeley dancer; and his father, renowned ASC member Jordan Cronenweth, served as director of photography on Blade Runner (AC July ’82), Peggy Sue Got Married (AC April ’87), Altered States (AC March ’81), Gardens of Stone (AC May ’87), and many classic music videos for leading artists of the 1980s and ’90s.

Taking this lineage a step further, Jeff Cronenweth has also collaborated with his brother Tim, a successful commercial director, on more than 500 spots.

“A storyteller doesn’t want to tell the same story over and over, and I don’t want to, either. I always want to find something new and challenging to work on.”

— Jeff Cronenweth, ASC

Cronenweth’s career path began with 2nd-AC work on commercials as staff loader at the commercial production company FilmFair, after which he enrolled at USC’s film school — where his graduating class included director Phil Joanou and cinematographers John Schwartzman, ASC, and Robert Brinkmann. He soon landed gigs as a 1st AC for many of the cinematography giants of the era, including Society members Conrad L. Hall, Sven Nykvist, John Toll, Haskell Wexler and Vilmos Zsigmond.

Recalling those early days, Cronenweth says, “In the beginning, it was overwhelming maintaining the camera and the camera department, but as I became more proficient, all of that became second nature. I really started appreciating my spot in the front row watching master cinematographers work, operators composing shots, and just seeing the whole ballet that takes place on a set with a cinematographer, the crew, the director and the actors.”

Invaluable Apprenticeship

Cronenweth’s father was among those he served as an AC, which enabled him to learn from a highly innovative artist. That gig also led to what proved to be a very important relationship — creatively and personally — with Fincher.

Fincher recalls a moment that says a great deal about the senior Cronenweth’s approach to lighting. The director sets the scene: For Madonna’s haunting music video “Oh Father,” the girl playing Madonna as a child is inside her recently deceased mother’s closet, playing with a necklace, when her angry father opens the door and berates her. “The girl was lit by a window and a single practical,” Fincher recalls. “The door would open, and we knew we’d need more light to hit her face. Jordan just moved some of the clothes inside the closet around to create some bounce, and it looked beautiful.

“I love when a cinematographer figures out a way to key someone without just setting a light and focusing it on them,” Fincher adds. “The human face responds to light in so many ways. It can come from the ceiling and spill over them, or it can bounce off the floor or come from a monitor. The cinematographers I’ve always admired and worked with are very conscious of this. Jordan was excellent that way, and Jeff innately has that sensibility, too.”

On Fincher’s first feature, Alien3 (AC July ’92), father and son worked together during the early days of the project before 20th Century Fox — reflecting well-documented anxiety about the production due to a variety of issues — replaced the elder Cronenweth with Alex Thomson, BSC after several weeks of shooting.

The film’s massive set was built on the famed Albert R. Broccoli 007 Stage at Pinewood Studios in London, and Jordan was not in the best of health at the time. “It was very cold in there,” Fincher recalls, “and it was difficult to get in and out of the set. It fell to Jeff to do some of the ‘recon.’ He was climbing around in there with his meter while also keeping a ledger of everything [Jordan and the rest of his crew] were doing, all the time-ingesting a lot of what made Jordan so special.”

Honing His Skills

Cronenweth started shooting music videos in the mid-’90s. “It was the heyday of the art form,” he recalls, “with directors like Fincher, Michael Bay, Dominic Sena and Mark Romanek doing work that was often more experimental and interesting than what we were seeing in features.” One such project he shot was for the Nine Inch Nails’ track “The Perfect Drug,” directed by Romanek, who has remained a frequent collaborator of Cronenweth’s on music videos, commercials, and other projects that include the feature One Hour Photo and the Amazon Prime Video miniseries Tales From the Loop.

The “Perfect Drug” video had a roughly $2 million budget, five shooting days, massive sets, and “very progressive, innovative [photographic] styles and light sources,” Cronenweth says. “I came into [shooting music videos] going, ‘I don’t want to be like everybody else.’ I admired my father’s work so much, because he was extremely bold and took chances and pushed film stocks and lenses to the extreme. It just seemed natural for me to take a similar approach.”

The cinematographer describes some bridges in the song where he keyed with Lightning Strikes units gelled green to represent absinthe as the “perfect drug.” Cronenweth adds, “It came off as so elegant. I’d have been hard-pressed to find a reason to use a technique like that on a movie, but we had opportunities like that all the time on music videos.”

Romanek recalls not only the cinematographer’s standout work on the job, but also the work ethic that he brought with him to the set. One day early in production on that Nine Inch Nails video, the director noticed that Cronenweth seemed a bit tired. It turned out that his father and mentor had died the previous day. “I didn’t even know at first,” Romanek says. “Jeff was dealing with grief and planning his father’s service while he was working on the pre-light. These were 14- [or] 15-hour days, and his lighting on the video was exquisitely beautiful. Later on, he told me he’d thought of his work as being in honor of his father.”

Breaking Into Features

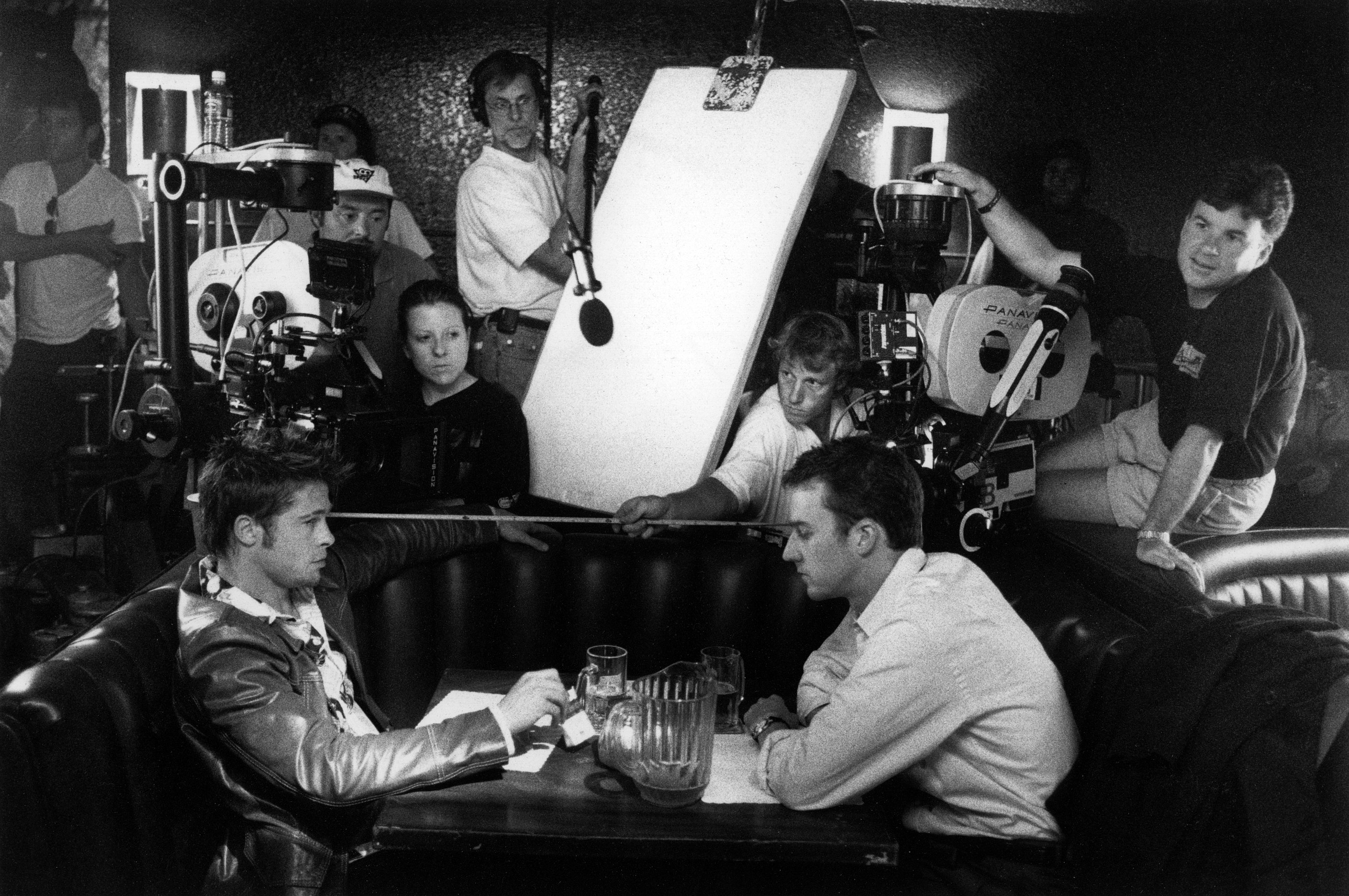

When Fincher was prepping Fight Club, Cronenweth had done some 2nd-unit shooting and operating for the director’s films, but at that time he hadn’t yet shot a feature — and making that transition from music videos and commercials was still a significant leap for a cinematographer. Therefore, when the director invited Cronenweth to his house to read the Fight Club script, the latter assumed he was being asked to do his usual 2nd-unit work (as he’d done on Seven and The Game), which still would have been an exciting opportunity.

“I knew the story, and it was all about breaking rules,” Cronenweth recalls. “The script itself is so irreverent. It’s about fighting back against established concepts, and Fincher, in general, is fairly irreverent. It was certainly something I wanted to be part of.”

But when he arrived at Fincher’s house, Cronenweth recalls, the director said, “‘Read the script and let me know if you want to shoot it.’ In my head, I didn’t really need to open it — this was an incredible opportunity with a very talented director, friend and great cast. So, I tried to put my best game face on, walked [outside] with the script, and — once I was safely inside my car — I started yelling! I read it in two hours and said, ‘Yes, I’d like to shoot it!’”

Cronenweth is “very humble,” Fincher says. “He might look at Fight Club as this big break, but I look at it as the natural evolution of what we were already doing. On Alien3, he and his father had been like one person. Later, he had operated on some 2nd-unit work we did on Seven when Darius Khondji [ASC, AFC] wasn’t able to return for reshoots. Harris Savides [ASC] was shooting and Jeff was operating. Sometimes I’d break Jeff off [on his own] and say, ‘Go across the street and find me a shot.’ I say this with humility: There aren’t a lot of people that I’d just [ask] to ‘go get me a shot.’ I’m not talking about trust so much as the knowledge that he wouldn’t need any handholding. I knew he’d come back with exactly what we needed.”

Cronenweth was invited into ASC membership in September 2002, with recommendations from Society members Bing Sokolsky, Ernie Holzman, Steven Poster and John Toll.

Mixing It Up

Cronenweth has gained a reputation for shooting in low light, often wide open, and for photographing faces that are exposed well under key. That kind of work on films such as The Social Network and The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo (AC Jan. ’12) — both of which garnered him Oscar and ASC Award nominations — has earned him a reputation for embracing darkness in the way that his father and other ASC greats, like Savides and Gordon Willis, had done. Film students have studied his use of subtle top and edge lighting to outline the subjects in otherwise very dark scenes.

But the cinematographer stresses that he does not want people to think there’s a “Jeff Cronenweth style” — because, he maintains, that style doesn’t exist. Instead, he prefers to work on a variety of projects that allow him to adapt to the material. For example, after shooting many big-budget features, videos and commercials, he took on the 2018 movie A Million Little Pieces, a $4 million production based on writer James Frey’s controversial book. “It was a 21-day movie,” Cronenweth says. “So, it was rather quick [compared to] what I was used to, which was one of the reasons I took it.”

Director Sam Taylor-Johnson had previously worked with Cronenweth on a fragrance campaign before reteaming for Pieces. “We had an immediate rapport,” she recalls. “There’s a quiet confidence in him that feels like it’s just in his DNA. I can sometimes talk a million miles a minute and fire off a million thoughts, and he will process them and come up with something perfect. He has a sort of stealth stillness that I think is the result of his having a laser-sharp focus.”

One of the director’s favorite scenes in Pieces is a hallucinatory moment in which the character James (Aaron Taylor-Johnson), dressed in a hospital gown, walks down a hospital corridor toward the room where he will be attending rehab. “He’s mentally fragile and feels like the corridor is swimming in excrement,” she explains. “He’s frightened, but then he starts to understand: ‘I live in shit. It’s something I’m familiar with.’ So, he dances through it all and slips and then slides into rehab that way.

“We had no money to do this, and we certainly couldn’t create something digitally. So, we made up paints and glue and water and paste, and we mixed it up in a big bucket and then used a hand pump to pump this stuff through rubber tubing. Jeff helped tremendously — not just figuring out how to light this space, but with nailing the tubing to the wall, drilling little holes, mixing it up to get the right consistency. And we could only do the scene once because we didn’t have anything we’d have needed to clean up the hallway and repaint it. That scene is really one of my favorites in the movie, just because I know what we pulled off.”

While Cronenweth’s music-video work certainly contains dark, disturbing and frightening imagery — exemplified by “The Perfect Drug” — his creative vision isn’t limited or compartmentalized. For example, his work on Taylor Swift’s “Shake It Off” video (which, to date, has drawn more than three billion hits on YouTube) presents a high-key look that’s appropriate for the up-tempo dance-pop song.

“He’s not just ‘the Fincher guy,’ [or] the ‘prince of darkness,’” says Romanek, who directed the “Shake it Off” clip. “We recently did a very comedic spot for a new app, and it’s really different from anything we’ve done before. I don’t think there’s any kind of story or style [that a production might call for] where I’d think, ‘He’s not right for that.’”

Being the Ricardos

Jeff Cronenweth, ASC recently reteamed with writer-director Aaron Sorkin (who penned the screenplay for The Social Network) on the feature Being the Ricardos, which finds its drama in the personal and professional lives of Lucille Ball (Nicole Kidman) and Desi Arnaz (Javier Bardem). Set in 1952 and based on real events that Sorkin telescoped into a one-week period, the film interweaves a collection of potential crises that threaten production of the trailblazing sitcom I Love Lucy.

Sorkin has been vocal about the extent to which he views Cronenweth and production designer Jon Hutman (The West Wing, Quiz Show) as “co-authors” of the film. “They’re used to working with directors who can speak to them with a more sophisticated vocabulary about the visual elements of a film,” Sorkin humbly notes, “but they were able to understand my unsophisticated vocabulary about visual elements in the film and translate that into something beautiful.”

For a series of flashbacks to the couple’s pre-superstardom days, Cronenweth decided to approach the lighting in a style that recalled the work of specific still photographers of the era — including George Hurrell and the cinematographer’s own grandfather, Edward Cronenweth. “I used hard lights and specific bands of light in a much more stylized way than we’re used to today,” he says.

Sorkin adds, “Jeff had told me his plan, but I was not able to visualize it exactly. I just trusted him, and it was a perfect approach for those scenes.”

Cronenweth had his longtime gaffer, Harold Skinner, steer clear of LED units. “We were dedicated to the type of light they used in the era,” he says, adding, “there’s nothing quite like the beauty of a tungsten globe. The combination of the lighting with the production design and the wardrobe lent the film a really wonderful, magical ’50s look.”

The cinematographer shot with the Red Ranger Monstro, using Red’s Helium Monochrome for the film’s I Love Lucy recreations and paired the cameras with Arri’s DNA lenses.

Sorkin points to one of many scenes in the film that exemplify what he means by “co-authorship”: a key moment between Ball and writer Madelyn Pugh (Alia Shawkat) where they argue about essential aspects of the Lucy Ricardo character. The scene takes place in a small space at the end of a hallway near the I Love Lucy stage. Sorkin recalls, “Jeff asked Jon Hutman to put a window in a specific area to help him light this little nook.” He adds with a laugh, “Jeff loves to blow out windows — he likes to have it going supernova outside! But that created a very nice effect that allowed us to have the [actors] take a step one way and go into silhouette or take another [so the light would] just wash over them. It worked perfectly for the scene. The script just says, ‘Interior Corridor — Continuous.’ I might have [also] written that some light comes in from somewhere. What Jeff did with that was beautiful.” — Jon Silberg

Cronenweth also recently participated in our ASC Clubhouse Conversations discussion series, talking about Being the Ricardos, accompanied by Sorkin, and interviewed by Caleb Deschanel, ASC.