American Cancer Society’s “Smoking Fetus”

Directed by David Fincher and shot by Michael Owens, this PSA gained national attention due to its striking images and potent warning.

This article was originally published in AC August, 1985.

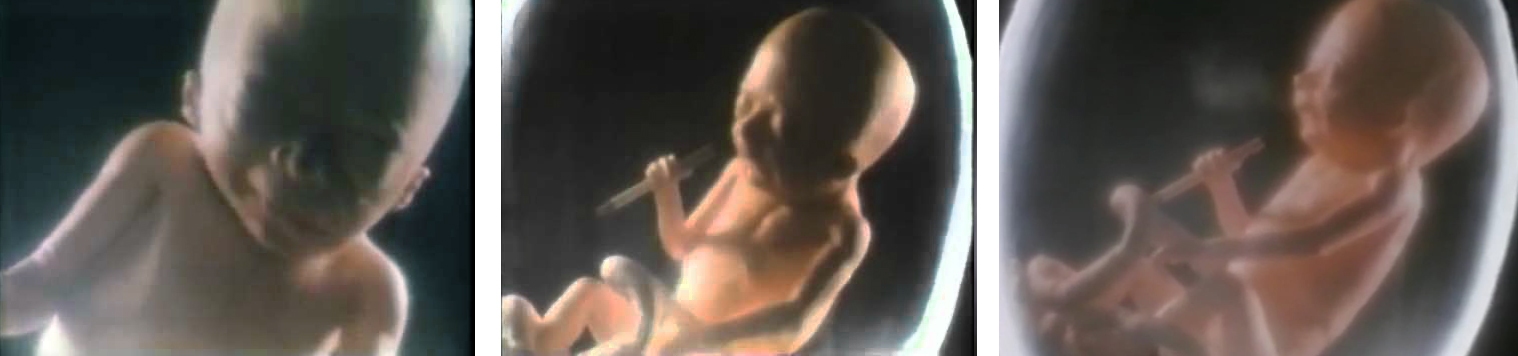

The sound of a heartbeat is heard. A human fetus fades up on the television screen in close-up and a voiceover begins: “Would you give a cigarette to your unborn child?” The camera pans and dollies back to reveal an entire fetus existing serenely in the womb of its mother. “You do every time you smoke when you’re pregnant.” At this point, the fetus slowly brings a lit cigarette to its lips and takes a puff, exhaling the smoke into the glowing placenta it lives in. And the voiceover finishes: “Pregnant mothers, please don’t smoke.”

The 30-second spot was produced for the American Cancer Society by a talented and relatively untapped group of San Francisco Bay area filmmakers, modelmakers, and computer specialists brought together by producer Joseph Vogt (Rick Springfield’s “Bop ’Till You Drop”). With a film and conceptual design education behind him, Vogt organized the majority of his film crew from the ranks of Industrial Light and Magic. It was with the abundant talents of these production people — director David Fincher, Midland Productions, and Monaco Labs — that Vogt brought life to a most creative and technically challenging public service announcement.

Jerry Angert, director of broadcasting with the American Cancer Society, described the ad as “one of the most powerful we have done... We considered the fact that it would be controversial and the networks might not show it, but counted on the local stations to take it." And that's exactly what transpired. NBC and CBS chose not to air the graphic spot while CNN (Turner Broadcasting), ABC and its affiliates and affiliates of NBC and CBS elected to show it.

CBS and NBC claim the spot is too graphic. An NBC spokeswoman cited “general taste considerations” as a deterrent to airing the spot. “It was the sight of the fetus that was especially shocking and we felt it was potentially offensive to our viewers,” she was quoted as saying. A CBS spokesman said the network agreed with the “importance of the intent of the message,” but said that the spot was “far too graphic for broadcast on CBS.” An ABC spokesman, however, said the message put forth by the spot was “important for pregnant mothers to understand.” The network felt that. while it was “different visually” from the usual fare viewed on TV, it contained no material that warranted its ban from the airwaves.

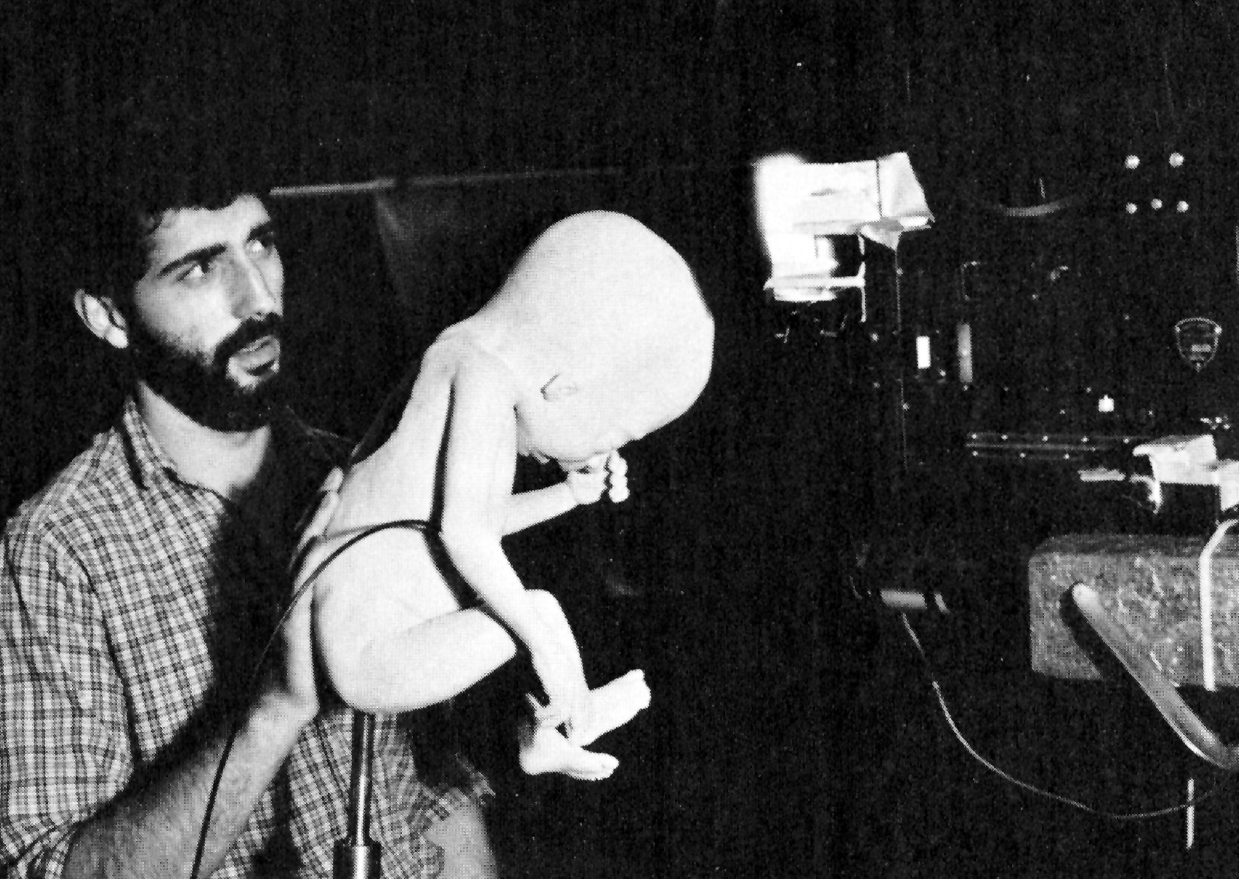

The 2'-long fetus puppet is starkly realistic to the camera’s eye. Sculptor Tony McVey is the main force behind the creation of the image that caused discomfort at two major networks. With four years of work designing and sculpting parts of human figures at the Natural History Museum in London, McVey’s background made possible a realistic fetus form from plasticene, an oil clay.

Joe Vogt provided McVey with the book “A Child is Born,” to aid him in the design of the most important element of the spot. The fetus McVey sculpted was next cast in a gypsum cement mold, a high-grade Plaster of Paris. A mold of the fetus was cast in eight pieces to avoid undercuts and then baked for five hours. Once done, McVey was ready to apply talents cultivated on productions of The Dark Crystal, Gremlins and other Lucasfilm productions. On these projects, many creatures were sculpted, cast and fit with cable-controlled armatures for eliciting movement in the arms, fingers, legs and head. It was the armature technique that allowed the movement of the cigarette to the lips of the fetus. And it was this gesture which has been the major object of controversy with the spot.

Fitted with a mechanical aluminum joint comprised of a ball, socket and hinge system, McVey assembled the cast pieces around the partial armature. An exit point for the armature cables was made at the elbow. Both the hands and feet of the fetus were wired for positioning purposes while two fingers of the hand that held the cigarette were cable-operated via the partial armature system.

The next step in bringing the figure to life was to transform the eight-piece mold into a humanlike context.

Foam latex, a rubber-based material known also as gum latex, was applied to the mold for the outer layer. Fiberglass layers then made up the structure of the head and rib cage, both hollow. The legs and non-moving arm consisted of foam latex only.

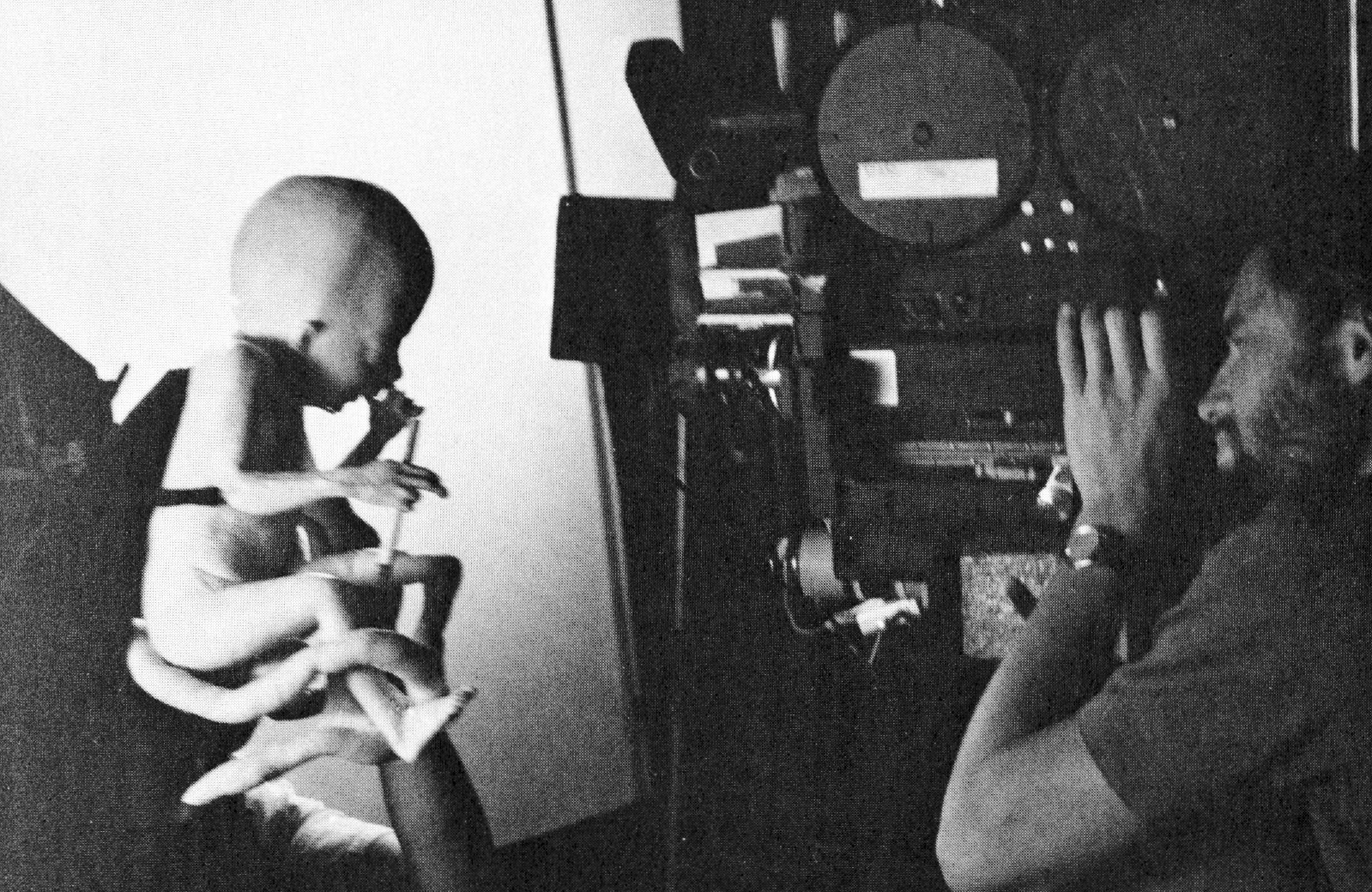

Sculpted details of the face and mouth added the realistic dimensions that breathed life into the fetus. With a hole placed at the upper back, a hand was able to move the mouth and lips of the foam latex face to provide the simulation of a mouth inhaling smoke. Mc Vey completed the fetus· looks by painting it a flesh tone and detailing the entire figure.

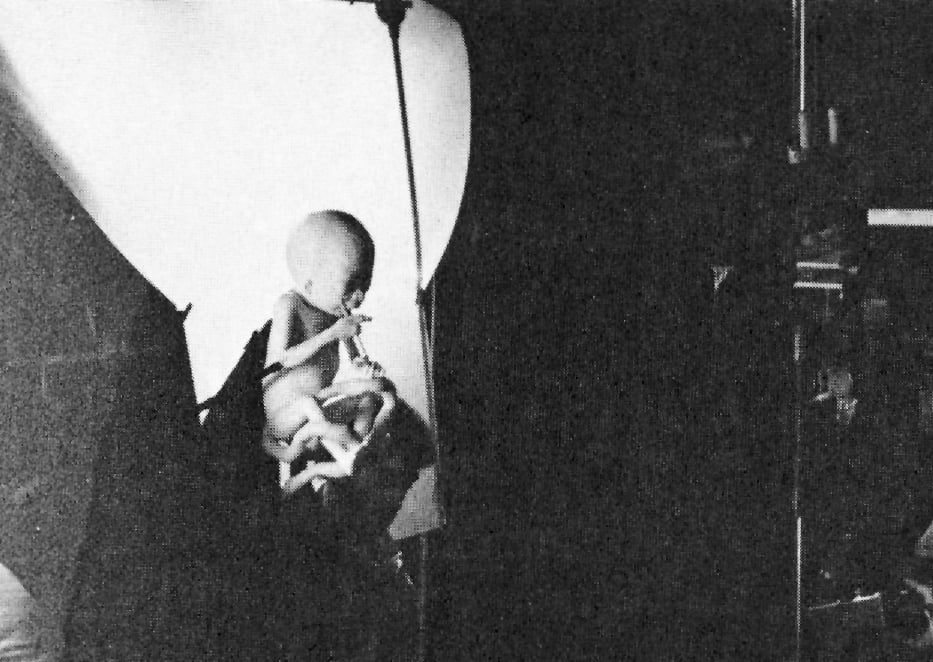

Puppeteer Bob Cooper added his talents to the image by designing an oversized cigarette. A large cigarette was necessary since a fetus is extremely small at the six-month stage in its life. The end of the cigarette was made to glow within the womb by use of a rheostat-controlled light. The smoke that the fetus exhales was blown through a tube leading up through the back of the fetus to the mouth. Shooting the fetus became an even more challenging endeavor, requiring three puppeteers to bring it to Iife.

Joe Vogt began the project by approaching the American Cancer Society with several storyboarded concepts conceived by designer Chris Green. Working without an advertising agency, Vogt secured a contract with the ACS for the $25,000 production costs.

With the fetus puppet in hand, the next step of the production would follow: Filming it within the placenta. For this stage of production, Midland Productions of Richmond, CA, and Dr. Steven L. Horowitz, PhD, general manager of Midland at the time of the production, were contacted by Vogt. At Midland’s motion-control and special effects facility, Vogt’s production was offered the computer-enhanced, motion-control camera system to bring the fetus and its environment alive.

Horowitz was commissioned by Midland to design a computer hardware and software system for the motion-control camera system that meticulously controlled the camera movement from the first close-up to the final full shot of the fetus within the 30-second spot. A Digital Equipment Corporation LSI-11 microcomputer is the main ingredient in Horowitz’s computer-program design. The microcomputer can synchronize the simultaneous motion of up to 16 axes of motion. For the shot of the fetus only seven axes of motion were controlled by the computer: roll (pan/tilt), vertical, horizontal, track, pull down shutter, focus, and model pan.

The software, as written by Horowitz, is programmed to allow control over each axis of motion. As he describes, “The camera movement is programmed with a series of six different points (key frames). At each point you define the position of every axis of motion including focus. The software program allows stopping the movement at any point to fine tune an axis of motion.”

In a period of two days, the motion-control equipment shot the fetus movement for a total of 12 takes. Coordinating the “burning” cigarette, the smoke exhaling from the mouth, and programming the motion-control movement to time well with the fetus movements took some precise work.

Camera operator Byrne Pedit programmed the motion-control camera using Horowitz’s software. Having focused the Mitchell GC 35mm high-speed camera between 1/2" and 1” from the fetus puppet, Pedit plotted out in the computer the direction and movement of the camera according to the desired frame positioning.

The camera’s first position was designated next to the fetus, perpendicular to its face. The final camera position was to be 12' back and directly in front of the fetus. Between the first and final camera position, Pedit was able to program the camera’s movement along six different points. Inclusive in the seven axes of motion mentioned earlier, the pan axis of motion was converted to the roll axis of motion with the use of an arm mechanism attached to the camera. The arm mechanism was able to rotate 90 degrees to achieve the end position in front of the fetus.

The Mitchell GC camera was equipped with a Nikon 20mm lens and mounted on a flexible mounting system. The camera shot the fetus at 48 fps with an aperture of f8. A number 6 Harrison filter was used for the desired soft-texture effect of a fetus floating in the placenta. By using a three-quarter backlight design, some undesired highlight effects on the foam latex skin resulted. To tone down these highlights, talcum powder was used.

Director of photography Michael Owens was in charge with Pedit collaborating on the lighting design. With a background of six years at ILM on productions such as Star Trek II, E.T. and Return of the Jedi, Owens was certainly not new to lighting and shooting models. The main difference, was that the fetus was no Lucasfilm fantasy creature. According to Owens, lighting the fetus was “like lighting a human or humanoid. It was a more realistic romantic situation compared to ILM models... it was enjoyable because it had elements of both [human and model] ... natural lighting for humans and model lighting.”

A heat-shrunk, clear plexiglass half dome was filmed separately from the fetus. Six takes of the dome image were shot over a two-day period. Once the half dome was partially backlit, it appeared too jewel-like for the placenta image. To reduce this glistening appearance, the dome was painted entirely black, streaked with gray and white paint and dusted with talc in certain areas. Specific highlights on the model and dome resulted from the painting techniques while the use of a heavier Harrison diffusion filter softened the overall image. The dome footage was also shot at 48 fps.

Midland Productions’ optical system is a computer-controlled eight-axis aerial-image printer equipped with Nikkor lenses and a Graphtone-designed lamphouse. The computer-controlled printer created a married composite print of all the elements of the spot: fade in, fetus and dome footage, American Cancer Society title, and the fade out. Eastman 5294 was the original camera stock used for the fetus and dome footage.

lnterpositives of the fetus and dome negatives were contact printed for the first stage in the optical process. The fetus was printed in combination with a high-contrast “garbage” matte which served to remove extraneous objects from the frame (i.e. Cstands, elbows and heads of puppeteers). These IPs were then printed sequentially onto a dupe negative. At this stage, states Pedit, “Additional filters were added to the dome IP to accent the translucent quality that we were looking for in the married print.”

Once the dome image was optically composited with the model image, it surrounded and separated the model from the black void in the background. The desired effect of a fetus floating in the womb had been achieved.

The third and last element to be printed on a dupe negative was the artwork for the American Cancer Society title. This was shot on a rotoscope camera using high-contrast Kodalith film. All negatives and workprints were processed by Monaco Labs, San Francisco.

Joe Vogt completed the American Cancer Society spot by working closely with the talents of actress/announcer Jan Thomas and music composer Ren Klyce. He played all instruments including the Yamaha FM digital synthesizer which provided the progression of three very consonant chords opening up the spot. In the mix these chords were crossfaded into dissonant chords at the moment the camera pulls back to reveal the fetus drawing the cigarette to its mouth. The third track consisted of a simulated heartbeat produced by a Profit 5 synthesizer.

The American Cancer Society “smoking fetus” spot has gone on to win six major awards including the International Broadcasting Award from the Hollywood Radio and Television Society. It has also been nominated for an ADDY award presented by the American Advertising Federation.

Says Irving Rimer, vice president for public information at the ACS, “It is one of the most impressive, effective spots ever done in the anti-smoking campaign.”

AC's coverage on director David Fincher's subsequent feature projects include Alien3, Seven, The Game, Fight Club and Zodiac.

If you enjoy archival and retrospective articles on classic and influential films, you'll find more AC historical coverage here.