Alien3: In Space, They’re Still Screaming

Alex Thomson, BSC discusses the difficulties of shooting in corridors full of fire, and how Alien3 helped him in the wake of David Lean's passing.

Unit Photography by Rolf Konow and Bob Penn, courtesy of 20th Century Fox

Alex Thomson, BSC — one of Britain’s premier cinematographers — creates images of dazzling perfection, richness and clarity, images which have graced some of the most exquisite-looking films in recent memory: Legend, Ridley Scott's epic fairytale; Eureka, Nicholas Roeg's influential retelling of Citizen Kane; and Excalibur, John Boorman's visually magnificent approach to the King Arthur legend.

Though Alien3 is ideal subject matter for Thomson's rich photographic style, he might never have lent his expertise to the project had it not been for one of the greatest triumphs and tragedies of his career. Late in 1990, Thomson had been chosen by one of the world's undisputed filmic masters to photograph what promised to be his final masterpiece: the director was David Lean; the project was Joseph Conrad's Nostromo.

Unfortunately, Lean took ill and died, Nostromo shut down and a saddened Alex Thomson returned to London, wondering what he would do next. "I came back from France on a weekend and they called me on Monday to see if I could take over on Alien3," Thomson recollects. "I started work on Tuesday, which was about a week and a half into production. I was happy to do it; it kept my mind off what might have been." (There is a certain karmic irony to Thomson's twist of fate. As fans of the first Alien film will recall, the spaceship in that picture was dubbed the Nostromo.)

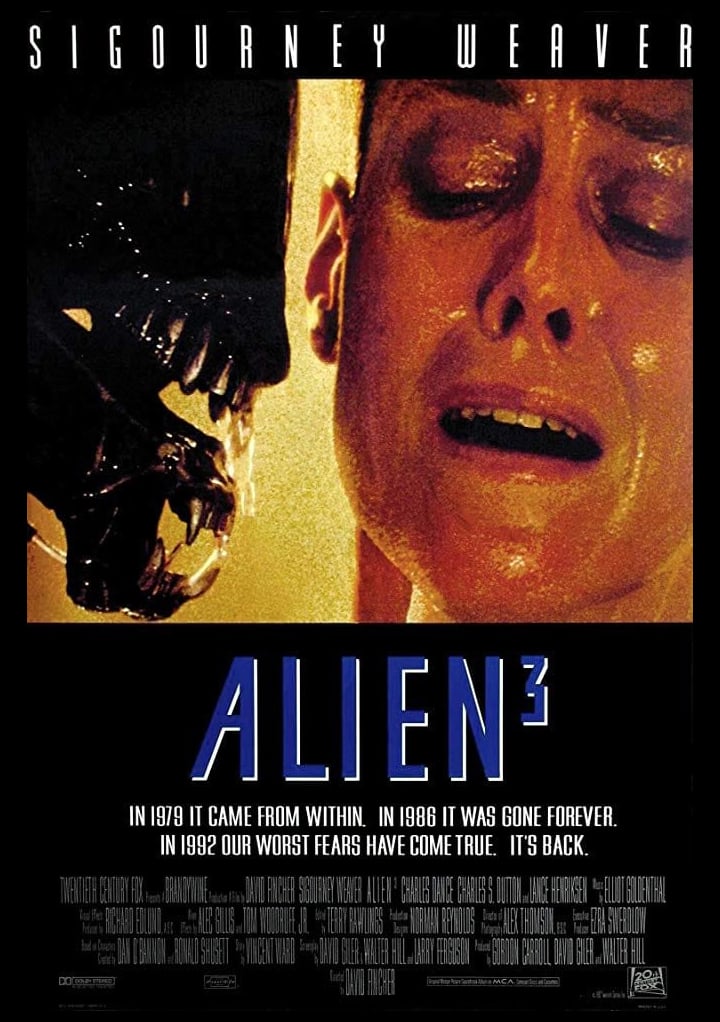

The production history of Alien3 is a troubled one. Before Thomson joined the film, its first director, New Zealander Vincent Ward — one of a slew of directors who had been attached to the project during its lengthy pre-production phase — had been replaced by rock video director David Fincher. Thomson was hired when the film's original cinematographer, Jordan Cronenweth, ASC (Blade Runner) left the production.

Many cinematographers might feel stifled by a production where the original look had already been determined, but not Thomson. "I had no problem with following in Jordan's footsteps because his approach was so right," he enthuses. "It was marvelous to be pointed in the right direction by a man of his caliber."

First-time feature director Fincher, for his part, is an award-winning rock video and commercials director with a background in visual effects storyboarding at ILM. "To take something over like this at 28 must've been quite awe-inspiring, but he handled it as if he'd done 20 pictures," Thomson relates.

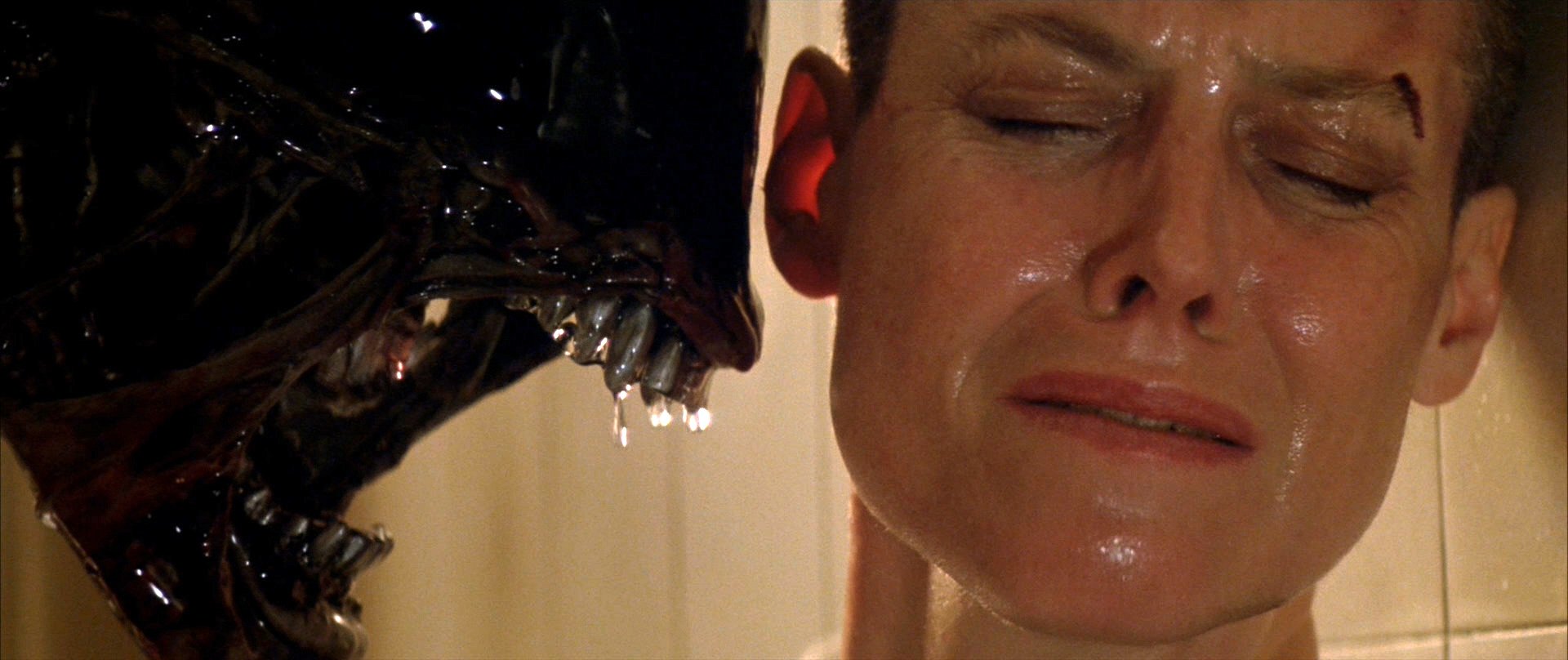

"The main interest in the picture is the style," Thomson continues. "Fincher was always saying, 'Keep it dark, keep it dark!' I took his point, because with an alien creature roaming about, it's not frightening if you can see all the edges and all the comers — you'll know the creature isn't there. We tried to keep it shadowy to create apprehension, mood and tension, but we had to see the actors so that the audience didn't develop eyestrain."

The challenge for a cinematographer, one would think, would be to find some variety in such a dark environment. "Quite the contrary," says Thomson. "I was trying to keep the whole thing looking the same. It's a great temptation when I'm on a film this long to do something different, but the audience is going to see it over a period of two hours while I've been on it for nineteen weeks. I think a film should have a consistent look."

There were other things Cronenweth had established before Thomson came on, such as the Panavision anamorphic format and the Kodak 5296 film stock. When asked if he would have chosen the same stock himself, Thomson submits, "I don't know that I would have. But I got used to it and liked it very much indeed.

"I used to be an old Fuji fan," he adds. "All of the films I shot from Eureka onwards, including Electric Dreams, Legend, and Year of the Dragon, were on Fuji until I got to Leviathan, when I started using Agfa. I used Agfa until Alien3, when I encountered 5296. The blacks are terrific, it's super-fine grain and it does everything you want it to. I'm very impressed with it."

Thomson's approach to fantasy films is to bring the impossible creatures and landscapes he photographs to vivid, colorful life. "I try to make it look as good as I can," he says. "I know it's quite fashionable to be wide-open on the lens —1.4 and 2.3 and so on — but I don't like it. In underexposing, you're dealing with the bottom end of the curve all the time and I don't think it's fair on the film. It denigrates the color. I tend to overexpose a bit and let them print it down. That way, because I'm working on the top end of the curve, it lessens the graying and enriches the color and gives the film a chance in the spectrum. Maybe that's the reason the colors are richer. When everybody else is at 6.3,1 always seem to be at 5.6. Especially with fast film these days, I seem to be at 4.5 or 5.6, which is where you've got to be for anamorphic film anyway."

Though a few scenes were set in the convicts' tiny cells, most of the sets were quite large, requiring a lot of light for the anamorphic format. This eventually posed a bit of a problem due to the unusual photographic approach Fincher had in mind. "I think practically every shot in the picture was a foot off the ground!" Thomson marvels. "Normally on a set you worry about what's on the floor and not what's on the ceiling, but Norman Reynolds, the production designer, had to change the whole thing around because we were looking up all the time. That's the style of the picture; it was Fincher's idea and I think it paid off."

The unique approach created one major challenge for Thomson and his crew—where do you hide the lights? "Down below on the floor," Thomson states. "Or through windows. There's always a corner you can tuck a light around. My main problem was the passages in the prison; they had no windows and were completely covered over, yet we were supposed to track down all of them! We laid the lights on the floor, around our dolly track and that sort of thing. We couldn't put them in front of us, though, because they would've thrown our shadows on the ceiling as the camera went past. These shots had to be back lit so the shadows of the camera and the boom and the crew and everything else would be thrown behind us. The problem was that since the lights were in front of us and we were tracking towards them, at some time we were going to see them, so I had to hide them with old tin cans and rubbish. That became quite a problem in itself because these were long tracks; when we used the Steadicam we were going around about a quarter-mile of corridors. I never lit anything from a gantry or a rail. I don't normally anyway, but on this one I couldn't because we were always looking up people's nostrils!

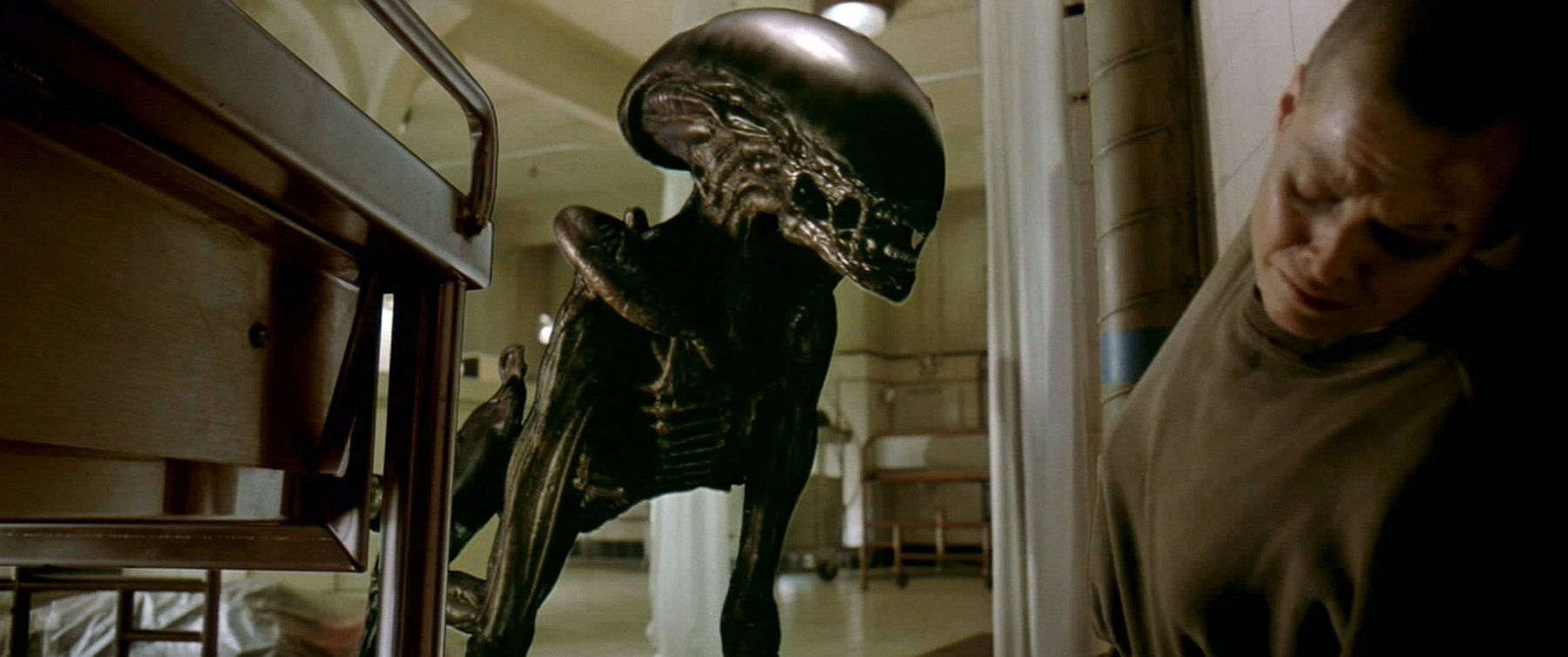

The January-to-June production schedule was due to the film's special effects, but despite the extra leeway, Thomson found he still had to race to get all the shots he wanted. "We were working fourteen to fifteen hours a day sometimes, six days a week, just because of the logistics. When you're dealing with sets of this size, it really takes time to build up steam, and after a few takes, you have to wait for the steam to build up again. The alien is basically only a guy in a rubber suit who can't stay in there forever, and there's not much he can do when he's got his false feet and hands on. He can't climb anywhere and he can't run, so we had to devise ways of making him do those things. Fortunately, the two people who created the alien on this picture also worked on the alien creature in Leviathan for Stan Winston, so I knew and trusted them and that made it easier."

Thomson had previously worked with Ridley Scott, the man who first breathed life into the Alien mythos, and he often thought of the filmmaker when it came time to shoot the creature's various evolutionary stages. "It's nice to keep light moving on the creature, which is something that Ridley taught me when we were shooting (the character) Darkness in Legend," Thomson recalls. "It leaves a lot to the imagination. You get an overall impression of what it looks like, but we never dwell on it. If you see it in its entirety, it looks like a guy in a rubber suit. Moving the light gives the alien a lot of animation even when it's not moving and lends to the excitement. The trick is to light the actors and not the alien."

Another trick was to create something that had never been seen in the series before — shots from the alien's point of view. Since the alien in this film is able to crawl up the sides of the corridors like a bug, its point of view not only had to be able to move swiftly through the prison complex, but also had to appear to roll 360 degrees. "Everybody talks about that shot, but it was done through the expertise of a Steadicam operator named Peter Robinson," Thomson explains. "Peter did a marvelous job. He literally ran through the corridors with a Steadicam and then, at the right moment, flipped it upside down. I've never seen that done before. I think we were down to 12 fps or a little less than that; it's the speed it's shot at that makes it look so fluid. Since it was supposed to be the alien's point of view, we shot it with a 10mm prime lens, not an anamorphic lens, so when you see it on the screen the image appears extremely distorted."

Smoke has become an essential element of the Alien films, not to mention the science-fiction genre in general. Alien3 has its share of ambiance, but in this case, where there's smoke, there's also an elaborate fire sequence. When Ripley convinces the convicts that the alien is afraid of fire, they attempt to burn it alive in the subterranean passages using old cans of gasoline. Of course, things never go quite right for the protagonists in these films, as Thomson relates: "Unfortunately, one of the guys drops his flare and ignites his petrol gel before everyone's cleared out of the corridor, so there's a sequence involving everyone rushing for safety amid huge explosions and flame — it's like a mini-Backdraft!"

Dealing with fire on such a scale took infinite caution and a great deal of time. Thomson's considerable ingenuity was taxed to its limit to capture the hellish imagery on film. "We shot this sequence for about four or five weeks, including the second-unit work," he says. "It's time-consuming to rest charges and to figure out where to put the cameras so they'll show the flame to its best advantage. The other problem is that there's some action before the flames and after, so I couldn't just expose for the flames. I wanted to build the sequence up so I could use a 5.6 for the beginning and post-flame; when the flame came, it was a bit stopped down. The flames only lasted a minute or two, so we had five or six cameras rolling at once. A lot of people tend to shoot flames wide open, but I always feel you lose the color of the flames that way. I like to shoot it at minimum of 5.6 so you get some color. As it turned out, it's pretty exciting stuff."

Recalling another sequel to a film made by James Cameron, the climax of Alien3 takes place in, yes, a metal smelting plant. "It's unfortunate that both Terminator 2 and our picture end up in a steel mill," Thomson sighs. "We didn't know that when we were making the film; in fact, we might've finished our principal photography before they did — we'll have finished shooting the picture almost a year before it comes out in May."

The site of the film's final sequence was actually a lead plant, as opposed to the steel mill of T2. The set, built at Pinewood Studios, consists of a huge pit supposedly filled with molten lead and a vast, moving gantry some 20 feet high and 15 feet wide that scoops up the molten metal and pours it into molds for shipment to other planets. It proved to be as challenging a setting to light as that of its counterpart in T2, and not surprisingly, Thomson found himself using techniques similar to those employed by Adam Greenberg.

"I was reading an interview with Greenberg in American Cinematographer [July 1991], and he talked about the steelworks at the end of Terminator 2. We both did more or less the same thing," Thomson remarks. "The set was quite huge. I had something like 600 fade bubbles down in this pit, which is quite a lot of light, but I had a lot of red and yellow filters actually over the lenses which cut the light down quite a bit. I also had masses of steam in the pit, and I had to use dry ice to cool the steam down a bit so it would stay over the pit. There was so much heat coming from the fights that the steam just shot up like smoke up a chimney. We were spending a thousand pounds a day on dry ice! Apart from the pit, I had about 20 dino fights — 24 power, 64 fights all in one unit — so we had a lot of fight, mainly because we were using such heavy filters that they just sucked the light out of there. It looks quite good."

In December, months after the production had wrapped, two and-a-half weeks of additional photography were required for shots needed to round out the film. A delighted Thomson found himself shooting at the legendary 20th Century Fox Studios in Los Angeles. "It was quite exciting to be in a major American studio shooting in Hollywood, and I was made to feel very welcome. Shooting on the Fox lot for me was one of the most exciting things I've done. I'd love to do a picture in L.A. at a major studio like that."

As far as his travails on Alien3 are concerned, Thomson smiles and remarks, "I'm pleased it wasn't my first picture; I might've been scratching my head a few times! It wasn't easy, but I enjoyed doing it very much, and it was nice for me because it was a kind of bonus. I was so disappointed and a bit drained emotionally because I was looking forward to working with David Lean. It was nice that Alien3 wasn't an easy picture because it kept my mind occupied. And no matter what the problem, we always got around it; I've never met the shot I couldn't do. You only think you can't do it when the director describes it to you, but you always can."

This article originally appeared in AC July, 1992. Some images are additional or alternate.

For more on the Alien franchise, check out Alien and Its Photographic Challenges, written by director of photography Derek Vanlint, CSC. Also, The Filming of Alien, penned by director Ridley Scott.

The followup film in the franchise, Alien Resurrection — shot by Darius Khondji, ASC, AFC — is covered here.

AC's coverage on Fincher's subsequent features include Seven, The Game, Fight Club and Zodiac.

If you enjoy archival and retrospective articles on classic and influential films, you'll find more AC historical coverage here.