ASC Master Class: On Film

A special session of the ongoing education program focuses on shooting with motion-picture stocks — ensuring that photochemical knowledge, expertise and creative passion is passed on to the next generation.

All photos unless noted by Nick Mahar. All images courtesy of the ASC.

On November 5, 2018, ASC President Kees van Oostrum welcomed to the ASC Clubhouse in Hollywood a group of 36 emerging cinematographers from around the world — there to attend a special session of the ASC Master Class. The focus? Shooting on motion-picture film stocks. The program was assembled to align with the growing trend of eschewing digital capture and going photochemical.

Van Oostrum noted this renewed interest in the medium, and added, “Many of our ASC members have started to pursue shooting on film again, so we felt it was time to revisit this in a professional way.”

The primary ASC instructors for this session were ASC members M. David Mullen (The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel), Edward Lachman (Carol, Wonderstruck) and Hoyte van Hoytema (Interstellar, Dunkirk) — as well as Linus Sandgren (La La Land, First Man), who was invited into Society membership shortly after the program’s wrap — all strong proponents of shooting on film.

“As the week goes on, don’t be surprised if you hear conflicting opinions. There’s no right or wrong way — many answers will be personal creative choices.”

— M. David Mullen, ASC

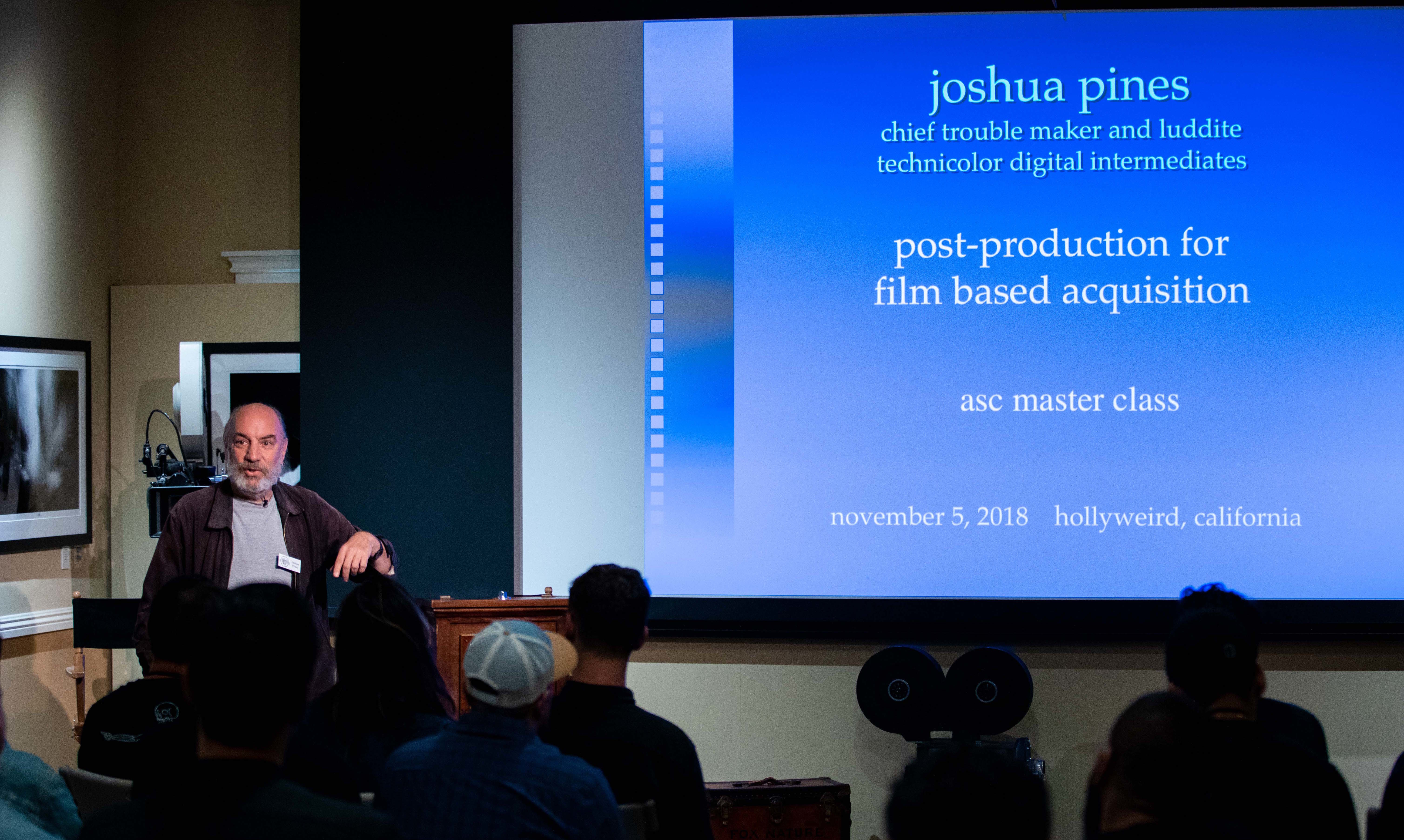

The first day was a primer in film as a practical and creative capture medium, including an in-depth lecture presentation by Mullen, as well as discussions featuring ASC executive director Eric Rodli, Technicolor vice president of imaging research and development Joshua Pines, and MJB Consulting president Mitch Bogdanowicz — all ASC associates — as well as Kodak president of motion picture and entertainment Steve Bellamy, Kodak regional technical director Beverly Pasterczyk, and ASC cinematographers David Darby and Steven Shaw.

Mullen, who said he’s shot more film in the last year than in the previous seven — including his feature The Love Witch — punctuated his opening presentation with a series of film clips to highlight the power and language of the filmed image, giving the students a deep dive into motion-picture history — and specifically into how advances in film stocks, color science, lab processes and camera systems affect the creative process of cinematographers.

“Since my video lecture on things I’ve learned by watching classic movies is made up of clips shot on film, I felt that more of the techniques I discussed would be directly applicable to the film-based workshops,” Mullen later explains. “I also feel that a lot of these ‘analog’ solutions to making movies still have their uses in a digital world.”

The first clips — focusing on collaboration between cinematographers and production designers — included John Ford’s How Green Was My Valley, which saw Arthur C. Miller, ASC work with art directors Richard Day and Nathan Juran, who built the Welsh mining village in Los Angeles-adjacent Calabasas. “The sets were designed for each camera angle,” Mullen pointed out. Another example was Stanley Kubrick’s Dr. Strangelove, shot by Gilbert Taylor, BSC, who worked closely with production designer Ken Adam, together creating practical lighting integrated into the set.

Other clips highlighted collaborations between cinematographers and costume designers, including Geoffrey Unsworth, BSC, who worked with Yvonne Blake to create Kryptonian costumes crafted from reflective 3D Scotchlite material for director Richard Donner’s Superman. To highlight collaborations with other departments, Mullen also screened clips of Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo, shot by Robert Burks, ASC, and Howard Hawks’ Ball of Fire, shot by Gregg Toland, ASC.

In the afternoon session, Mullen delved into the technology of film, laying the groundwork by discussing the chemical makeup of celluloid and emulsions, and explaining how exposure and processing results in an image.

With regard to choosing film stocks, he advised, “Using the slowest film stock that’s practical outside, and high-speed film inside, is one school of thought. Using daylight-balanced stock so you don’t need a correction filter is another.”

Rodli and Pasterczyk went into greater detail about the composition of film and how it responds to light. “Film sees things the way the human eye sees it,” Pasterczyk explained. “Consistency was key in the technical advancement of the way we make emulsion. Material innovations include antenna dye sensitization, advanced tabular grain technology, electron sensitizers, advanced development accelerators and high-activity couplers, as well as upgrades to silver halide crystals.”

Pines discussed real-world dynamic range, and then noted that “all cameras — film or digital — capture a limited range, and the final display has even less dynamic range.” He went on to express that it is in fact “built into our DNA to take high dynamic range and reproduce it on lower-dynamic media.” As proof, he pointed to a range of art, from pre-history cave paintings to Rembrandt’s masterpiece “The Night Watch.”

In the panel discussion, Mullen, Bogdanowicz, Pastercyzk, Darby and Shaw answered participants’ questions. On the minds of many students was the fact that most motion-picture labs worldwide have closed over the past decade. As a result, they were informed, Kodak has opened labs in New York and Mumbai, while also maintaining facilities in Atlanta and London.

When AC later asks Mullen about the potential loss of film-negative expertise among cinematographers, he replies, “I worry more about the loss of expertise in the manufacturing and processing side of film, which are much [more] complex processes requiring tremendous quality control and technical knowledge. But yes, producers are less likely to spend the money on shooting film if they are not confident in the cinematographer’s mastery of the format. As with any filmmaking approach, I think my job as educator is to demystify the process and emphasize the artistic possibilities, because I think some of the fear about using film is unjustified. It’s a very flexible and versatile process — and, after a century of improvements, near bulletproof for the user if they follow some basic guidelines.”

“The language of cinema is images, not words, with the subtext of the emotions of the characters and how they evolve.”

— Edward Lachman, ASC

On Wednesday, with ambassador Peter Levy, ASC, ACS in attendance, Lachman spent the day acquainting the students with his love of film, and leading a 16mm shoot. “It’s the image through the optics of the lens that tells the story,” Lachman said. “The language of cinema is images, not words, with the subtext of the emotions of the characters and how they evolve. With the director, you have to discover the metaphor, the emotional subtext of the images.

“The emotional connection I have with the crew is very important to me,” he added. “You can’t create all those images yourself. The whole is greater than the parts. You create a vision together.”

Lachman started his career shooting documentaries — 16mm cinema verité. “You had to make decisions on your feet, while operating,” he described. “For me, documentary was the greatest entry into cinema, and I feel like I’ve never left it. Documentaries are no different from narratives; it’s you experiencing something with your camera in time and space.” On entering into a narrative project, he noted, “You should go in with a game plan. Read the script, go to locations, block out scenes, have a shot list. But on the day, on set, you have to be responsive to what’s in front of you — the immediacy of documentaries.”

Lachman discussed his preference for a two-color palette — an advancing, bolder color and a receding color, which he also described as “warm and cool” — as a good way to create depth. “The digital world can have some striking images,” he suggested, “but the digital world is too clean and hyper-real, whereas film grain’s structure creates depth.”

He further suggested that just as there are different painting styles, the student cinematographers should “not limit their palette” by shooting only digitally.

Lachman described how he and director Todd Haynes decided to shoot the HBO miniseries Mildred Pierce on Super 16mm. “Todd and I were referencing a different time period and cinematic language, and we did that by shooting film,” he explained. “The film stocks wouldn’t look like stocks from the 1930s or 1940s, but I had the exposure latitude and color rendition of film, with the illusion of sharpness with the digital intermediate.”

For Haynes and Lachman’s feature Carol, the cinematographer noted that they had wanted to capture the feeling of a conservative, postwar period. “When you do a period piece, you have to [move] away from a romantic, revisionist view of the past,” he said. “And when you pick a style, you don’t know if it will work — but the important thing is to be consistent.” Even after a great deal of preproduction, Lachman recalled, he and Haynes were still surprised by one aspect of the imagery. “Only later did we discover the grain in Carol created a certain emotional quality for the characters.”

To shoot 16mm, Lachman and his students set up and shot in the ASC president’s office, to replicate as closely as possible how Sandgren and the students shot the previous day in 35mm. (Story below.) Lachman explained that he never uses diffusion with Super 16 and never pushes it. “If I use an incident meter, I leave it at 500 ASA and open [the lens] 1⁄3 of a stop,” he said. “When you overexpose a negative, you’re helping the saturation of the color and grain. With 16mm, you won’t have as much shape to the image as with 35mm; it’ll look a little flatter. That’s why I like to use the sharpest lenses I can, to get the best out of it.

“Going through a DI and digitally projecting Super 16mm is fantastic if you handle it properly,” he added. “It can look as good as 35mm, and I think you’ll see it in your own tests.”

For the Thursday session, the students met at IATSE Local 80 in Burbank to learn from van Hoytema, who brought his crew, comprising key grip Herb Ault, gaffer R. Adam Chambers and focus puller Keith Davis. Known for deftly operating the large and weighty Imax camera on his shoulder, van Hoytema even offered everyone in the class the opportunity to try that out. The cinematographer — who studied at the Lodz Film School in Poland, where students worked only with film cameras and mostly Orwo stocks — would only cover Imax in this session, rather than all the 65mm film formats, “because there are a lot of myths about the Imax camera, and I want to show that when you treat it like [any other] camera, it’s the same thing,” he said.

“You are effectively always looking at the same raster in digital, but in film, the silver halide is constantly [being replaced]. Theoretically, you should have a much better chance to capture detail with something randomized rather than rasterized.”

— Hoyte van Hoytema, ASC, FSF, NSC

The cinematographer passed around Imax contact filmstrips, noting (from his film Interstellar, seen at top of page) , “You can hold it up to the light and straight away see your exposure, your colors. [According to Imax] you need at least 18K to get close to the detail [of this format]. We say this is 18K resolution, but what does that mean? You [also] need to understand what resolution is over a period of time — 24 images every second. Within that [framework], you create ‘temporal resolution,’ which is a very different thing than counting pixels. This is one of the core reasons why I like film so much more than digital. You are effectively always looking at the same raster in digital, but in film, the silver halide is constantly [being replaced]. Theoretically, you should have a much better chance to capture detail with something randomized rather than rasterized.”

On using caution with Imax negative, he later remarked in a conversation with AC, “I think one can be slightly more ‘careless’ with such a big negative.” As he explained to the Master Class students, “If there is any medium you can expose with errors, it’s this one — [you] can expose it wrong and you’ll still have a glorious, rich image on the screen. I have to be careful, but not precious, with it. It’s a perfect medium, from bright sunlight to darkness. With all this latitude, you can maneuver through human error and still create something rock solid.

“Imax is a very visceral format. It’s like being ‘surrounded’ by the shot,” he added. “It’s not like shooting a smaller format, where composition becomes a more intellectual approach. I tend to frame more to center, like following a ping-pong ball in a match. It’s more active, so I frame for eye-scanning. Be aware of where you want the audience to look — and you have to think about your next step. With Imax, it’s very much about a direct emotional communication and connection. People never consume your image in an analytical way, but in a direct and emotional way.”

On the resurging interest in shooting on film, van Hoytema attested, “It’s starting to happen again. Film is a section of the industry that’s growing, and there’s a reason why people gravitate to film more and more.”

Imax camera technician Scott Smith went into greater detail about the Imax camera interior, while van Hoytema demonstrated Arri SkyPanels. Then every student in the class who was interested had a turn shooting with the Imax camera. “Don’t forget the juicy close-ups,” van Hoytema said. “One professor told me that symmetry is the aesthetic of scoundrels, and I never forgot it.” As he later noted to AC, however, “I don’t necessarily agree with that statement my professor made years ago!”

On Friday, van Hoytema and the students met at FotoKem in Burbank, where senior vice president and general manager of feature sales and marketing Andrew Oran gave everyone a tour of the lab, scanning facilities, QC and restoration rooms, and described typical workflows for a film finish and digital finish. “The only ‘secret sauce’ is having cinematographers trust you so they want to do their next film with you,” he said. “It comes down to the colorist’s relationship with the cinematographer — and good coffee.”

The group gathered in a grading suite, where Oran gave a presentation, which included a discussion of the film labs still existing in the U.S. and worldwide. Oran also described FotoKem’s NextLab dailies service.

Levy reminded students to “keep an eye on shadows, highlights and face skin tones. And when you shoot a slate, make sure there’s enough light to read it, you shoot it as close to full-frame as possible, and you keep it on the screen long enough to extract information.”

Digital-intermediate colorist Kostas Theodosiou advised students to “please give five or six frames of a framing chart and then a color chart, especially if you have mixed formats.” He went on to do a pre-color correction on some of the footage the students had shot earlier in the week.

The group next visited Imax headquarters in Playa Vista, accompanied by van Hoytema, Imax chief quality officer and executive vice president David Keighley, and senior vice president and managing director Patricia Keighley. In the Imax theater, students saw the prologue to Dunkirk and then their own 65mm footage.

When asked for his thoughts on participating in the Master Class program, Mullen notes, “The students in the Master Classes are always top-notch and very advanced, so they challenge you to be more precise and accurate in your answers. But they also often provide a glimpse into filmmaking in other regions of the U.S. and the world, which is very enlightening. However, what often results is the realization that most cinematographers around the world deal with similar challenges.”

Noting that this was his first opportunity to instruct in this ASC program, Sandgren remarks, “I learned that teaching a Master Class is a collaboration between the teacher and the students. I also learned a lot about how the younger filmmakers work nowadays.”

Van Hoytema relates, “I think the next generation will hold us bitterly accountable if we allow film to disappear. We should put effort [into education], and making the paths to access [the film medium] as easy as we can. Then they can judge for themselves if they want to pursue it or not.

“It is very important to create the opportunity for eager, aspiring cinematographers [to work with the film medium]. I want to keep reminding [them] of the beauty of it. These students had such a strong will to work with it, without being sentimental about it. I am very happy to be in a position where I can share my love for film, and even more lucky to find an audience of apprentices who were as passionate about it as myself. The future is bright. We owe it to the next generation of filmmakers to keep passing on this knowledge.”

Additional reporting by David E. Williams

Education and Inspiration

The Tuesday session of the special film-focused ASC Master Class was presented by Linus Sandgren, a member of the Swedish Society of Cinematographers who was recently invited into ASC membership. Sandgren centered the discussion on shooting 35mm film, and led a demonstration wherein a scene was lit and shot in the ASC president’s office at the Society’s Clubhouse in Hollywood. AC later spoke with the Oscar-winning cinematographer about the importance of shooting on film negative.

American Cinematographer: Were you specifically interested in teaching this session of the ASC Master Class because of the focus on film?

Linus Sandgren, ASC, FSF: Yes. To me, it’s important that film coexist with digital. My opinion is that over the last decades of experimentation, it’s been proven that digital cameras are indeed no replacement for film cameras, but are simply a different medium.

I think we have to look at the music industry, which was first to go through the digitalization. They learned to work with digital instruments side-by-side with, and not replacing, analog. It’s not like composers call out the acoustic guitar as dead because there are synthesizers that can create a similar sound. Similar to the visual arts, where oil paint can coexist with digital, film needs to coexist with digital. Therefore, I think it is important that the film schools, the academies, the societies, the vendors, the manufactures and the film crews continue to embrace the variety of capturing mediums — and continue to educate and curate the celluloid film medium as well. I am proud to be an advocate for the variety of tools, and will do my best to help educate and inspire others to embrace it.

Did you notice any major themes in regard to the information the students were looking for?

My feeling was that many of the students were already advocates of film, I noticed that it’s been a change among younger filmmakers that they’re missing something when working digitally, I feel that tendency from the world in general, what about real books, real paintings, real meetings eye to eye.

The students need support to understand it is not hard to work with film, it’s exciting and fun, and easy. And not necessarily more expensive.

Tell us about the importance of encouraging emerging cinematographers to develop expertise in film-negative work.

Sandgren: [When] the digital revolution [began], I think a lot of people chose to work digitally because they were either forced to by budget, or they were simply curious about new technology — and over time, fewer people learn to work with analog film. It is in the interest of diversity and variety within the cinematic arts that the forms of expression are many. I believe that without film, our tools to create a great variety of expression is very limited. And without people making films on [actual film stock], fewer people will know the craft.

It’s very exciting to teach younger cinematographers, who may not have had so much experience in this, that the options of expression are multiplied when you work on film. Shooting Super 16 and push-processing in the lab looks completely different than 65mm pull-processed [footage], and everything in between. The various film stocks register the world differently, and all these formats combined with multiple versions of optics and light give us many more variations of looks.

My goal [in teaching this session] was also to show how easy and quick it is to work on film, and how focused the crew gets when a camera is actually rolling. — David E. Williams

You’ll find more information about the ongoing ASC Master Class here.