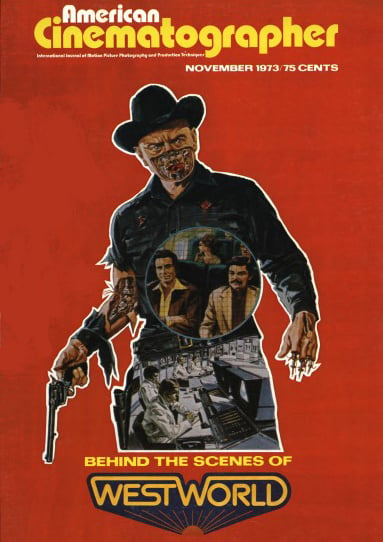

The Cinematography of Westworld: A State of Mind?

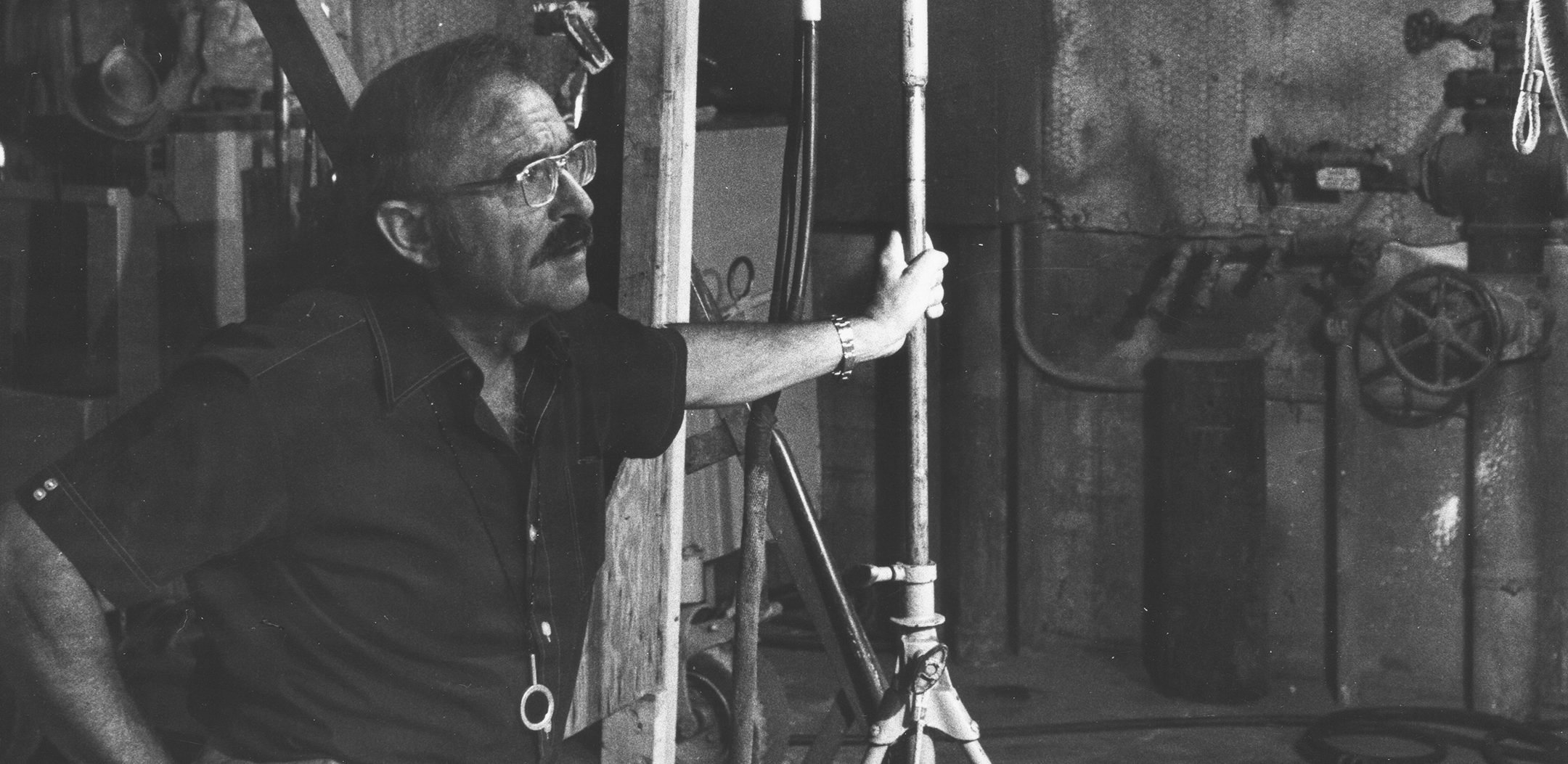

Director of photography Gene Polito shares his thoughts on the filming of MGM's provocative sci-fi drama.

By Gene Polito, Director of Photography

You will find a small sign posted above the starter's window at Los Robles Golf Course which reads: "Good golf is a state of mind — Arnold Palmer."

As a confessed "golf nut," I have reached the conclusion that Palmer's observation could apply equally to professional cinematographers. As a matter of fact, Directors of Photography have a lot in common with today's touring pros: the field is overcrowded, the competition is keen, the pressure is ever-present, the financial stakes are high, and the odds of coming up with a winner — consistently — are staggering. And — oh yes! — When the chips are down nobody is going to make that tough shot for you! Herein lies the daily challenge which faces touring pros and DPs alike. In retrospect I have come to realize that good photography — like good golf — is truly a state of mind.

“I could hardly wait to get into the script once Michael gave me a clue as to what Westworld was all about.”

The reader might well ask, "What constitutes an ideal state of mind for the Director of Photography?" Perhaps a glimpse of Westworld through the eyes of a cameraman will provide the answer. To begin with, "the chemistry was good" between the director, Michael Crichton, and myself. It is this particular ingredient that is most essential in the initial stages of achieving "a good state of mind" for the Director of Photography.

Very often the initial stage involves an interview between the director and the cameraman, who are total strangers to one another, on a personal basis. This can be a devastating experience for the new Director of Photography who is short of material (credits) to talk about. (Most cameramen — including myself — have been down this road before. There is no shortcut, other than a smash-hit on your first trip to the plate — and the odds against doing this are pretty high.)

Michael Crichton and I were total strangers when we first met. But neither of us lacked material by way of our respective backgrounds to provide the basis for a lively and interesting interview. The "chemistry was good" and Michael hired me to do Westworld. Thus, the first crucial element necessary to achieve a "good state of mind" was behind me. Moreover, I could hardly wait to get into the script once Michael gave me a clue as to what Westworld was all about.

“After reading the script for Westworld, my first reaction was that I had stumbled onto a gold mine...”

After reading the script for Westworld, my first reaction was that I had stumbled onto a gold mine — in the sense that it promised to be a rich experience for a cameraman. As it turns out, Westworld is the type of story cameramen dream about, but rarely — if ever — run into. Westworld offered four distinctly different visual backgrounds within the time frame of a single story. I thought to myself, "Imagine ... an action 'western', decadent Rome, the Medieval era, and a NASA-type space-age complex... all in one film!" But that's what Westworld offered me: four "photographic worlds" to work in.

Westworld opens with a prologue (ahead of the credits) which has a rather unique format in itself. We wanted this portion of the picture to hit the screen in an aspect ratio similar to the old Movietone News ratio (about 3 to 4). Since the picture was shot entirely anamorphic Panavision, I had Panavision inscribe special lines on the ground glass in order to shoot the prologue with an anamorphic lens, and yet allow us to compose for the Movietone format. In the release prints the unused portion of the anamorphic screen was simply blacked out in printing.

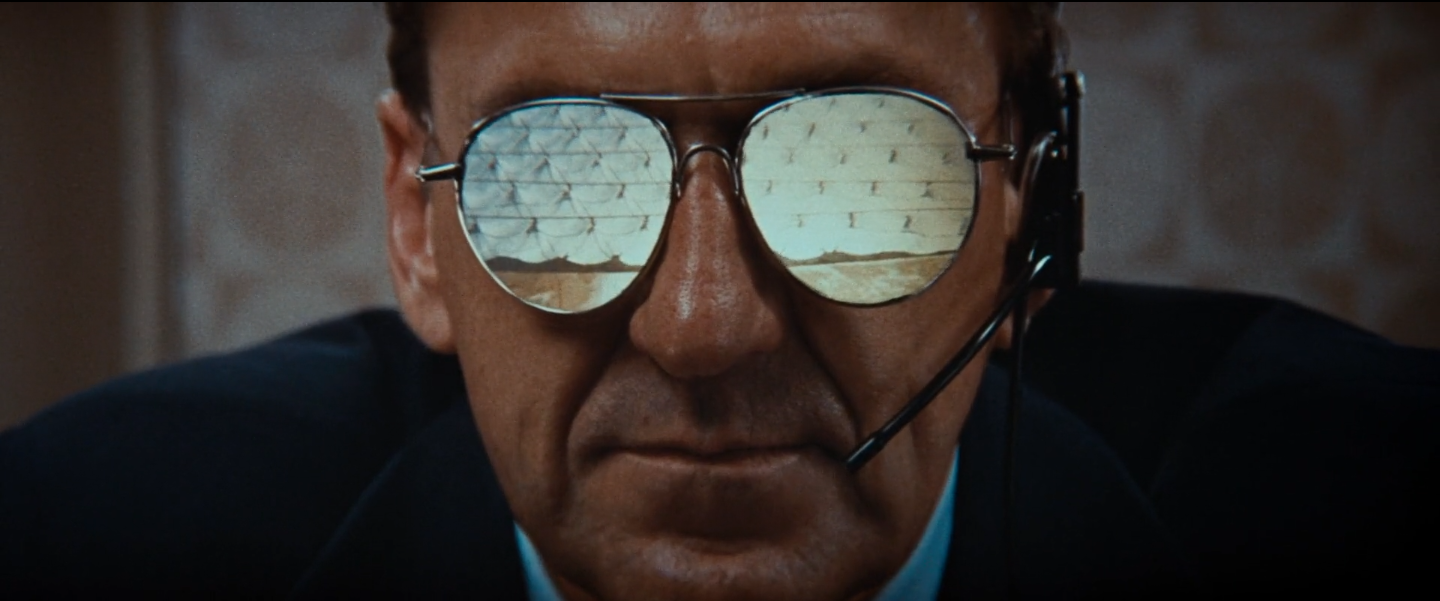

Following the screen credits, Westworld opens with a rather bizarre shot designed to "set up the audience" for the hovercraft sequence. In this instance, the hovercraft is an airborne vehicle (for the purposes of the story) that transports people to and from Westworld; it scoots very low off the ground at speeds of about 300 mph. The sequence opens on a close shot of one of the lenses on the pilot's colored glasses. At this point the audience has no way of knowing what they are looking at, other than the ground whizzing by at tremendous speeds. We hold on this for a beat and then zoom back to a full shot of the pilot's face where we see what he sees — namely, the desert whizzing underneath him.

“There is no formula for this and I must confess that the results were based on an educated ‘guess’ exposure-wise. It turned out great!”

To accomplish this shot, we used front projection onto the pilot's glasses by cementing front-projection screen material to actual sunglasses worn by the actor. The only difficulty here lies in the balance; it's tricky, because the front-projection image on the glasses becomes "very hot, very quick" and the balance between what you see visually projected on the lenses of the glasses, as opposed to the overall key light falling onto the pilot's face, becomes deceiving. There is no formula for this and I must confess that the results were based on an educated "guess" exposure-wise. It turned out great!

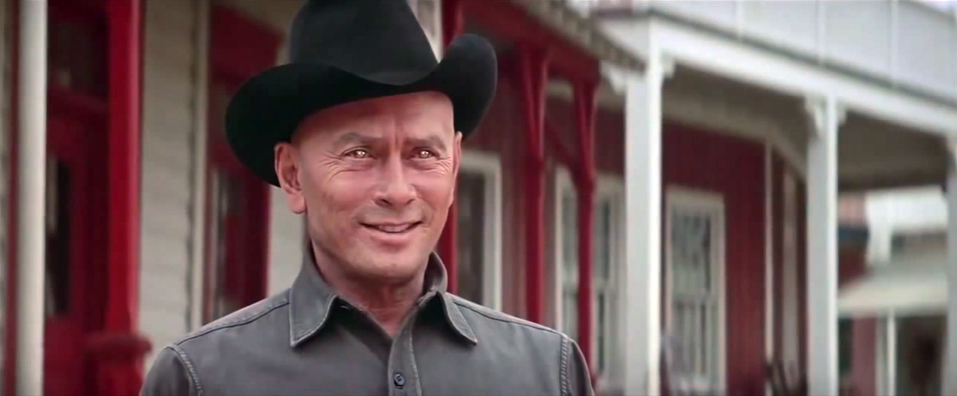

One of the main characters of Westworld is the Gunslinger who, in turn, happens to be a robot. The part is played excellently by Yul Brynner. Michael Crichton wanted the gunslinger's eyes "to look like electronic eyes" at a certain point in the film. Michael and I discussed various possibilities to achieve this effect. Tests were made using a variety of contact lenses which were silver-coated to produce varying amounts of reflectivity: 50% transmission, 50% reflectance; 80% transmission, 20% reflectance; 20% transmission, 80% reflectance, and so on.

“I’m sure there are those who will agree that some of the best work done in motion pictures is done under the pressure of time...”

At first, I was certain that by using a front-projection configuration, I could achieve the best results simply by shooting through a 50-50 mirror and projecting a light beam directly into Yul Brynner's eyes on the same optical axis as the camera (using the mirror). I was wrong; it does not work that way. Then we tried various ways to light the eyes by resorting to some of the techniques used in commercials, vis-a-vis a huge white surface with a small hole cut out for the camera lens. This proved to be too time-consuming and was discarded in favor of conventional lighting. Which brings up this point: when the chips are down, and the time is fast running out, some of the best answers to the worst problems seem to emerge almost by sheer magic. I’m sure there are those who will agree that some of the best work done in motion pictures is done under the pressure of time... and lack of funds. At any rate, we found that contact lenses with 20% transmission and 80% reflectance served our purpose the best without resorting to "exotic lighting techniques."

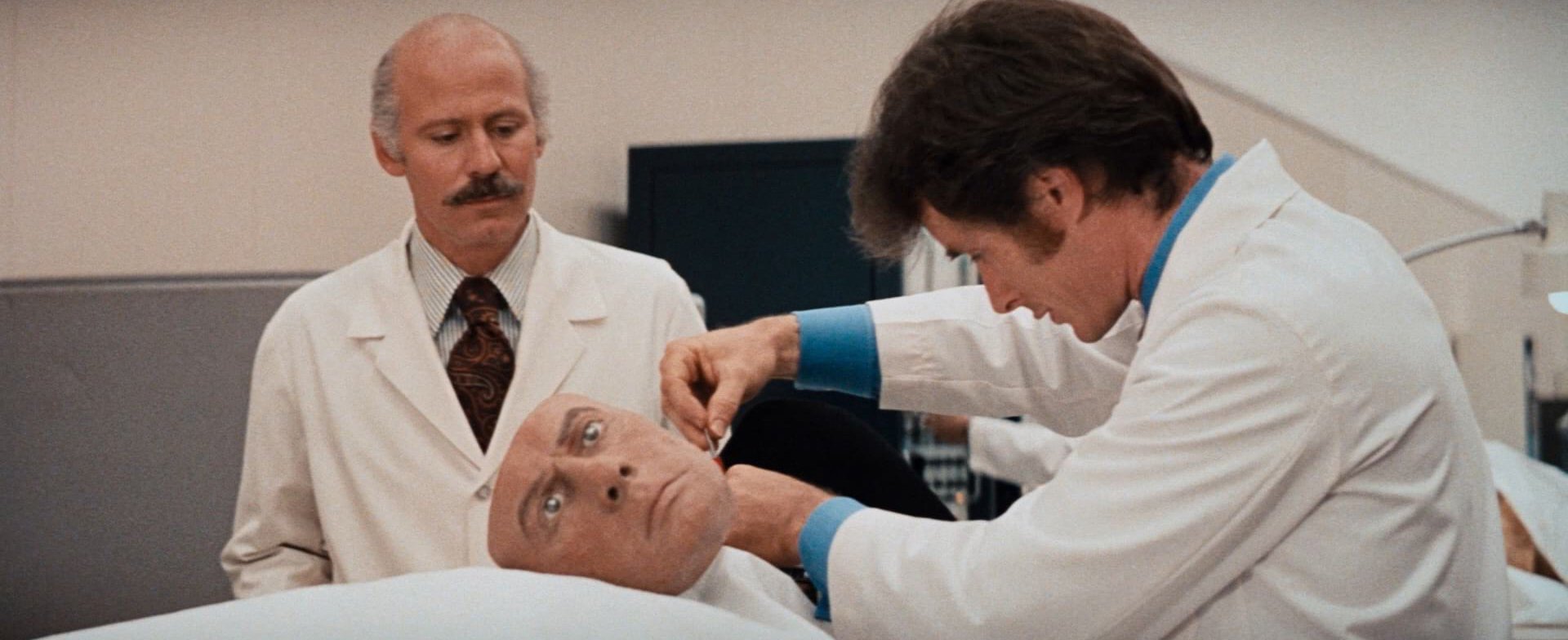

There is a point in the story where the Gunslinger (a robot, remember) is sent in for "repair." The trick here was to put the "real" Yul Brynner on an operating table for "inspection of malfunctioning circuitry." Then, by camera magic, we show the Gunslinger's face being lifted off, revealing all of the electronic circuit boards in his skull.

During the pre-production stages of Westworld a make-up man was flown to Paris to meet Yul Brynner for the purpose of casting his face. Therefore, when we got to this sequence, a plaster replica of Yul's face had been prepared in such a manner as to allow the facial portion to be removed to reveal all the "electronic guts" which were supposed to make him function as a robot. Needless to say, plaster and human skin do not have anywhere near the same characteristics.

In order to "match" the "live" Yul Brynner to his plaster reproduction, I worked for almost two hours (on production time!) with the aid of two make-up men and a Polaroid camera until the Polaroid stills of the plaster replica matched closely enough to the "real" Yul Brynner in texture and color. The results were so close that it even gave the guys in the lab a "shock" when his face was removed! (The audience responded right on cue, too.)

"Robot Repair" was a NASA-type complex complete with all sorts of exotic equipment, including a laser machine. This set was enormous and occupied the entire Stage 25 at MGM studios in Culver City; a stage measuring approximately 117 feet by 195 feet. It was encompassed for 360 degrees by a white cyclorama backdrop, 40' high, from the stage floor to the rafters. Some of the shots we had planned required the use of the Panavision wide-angle 30mm and 40mm lenses. This, in turn, meant that any thought of conventional lighting decks would be out of the question; the lights themselves would be in the picture, since we would be shooting to the very top of the cyclorama. Therefore, I decided to light this entire set with a soft-type of general overhead illumination. For this purpose we scrounged all over the MGM lot for all of the "chicken coops" we could find. Most of them had not been used for years. We gathered them all up and had them re-painted, re-switched, and re-globed. Each coop contained 10 1,000-watt silverbowled globes and was arranged to switch on 2, 4, and 10 globes (total 10,000 watts) to give us complete control. Naturally, on certain scenes, we used floor lighting equipment to supplement the general overhead lighting — where possible. The "chicken coop" arrangement produced about 125 footcandles evenly distributed over the entire set. This entire lighting scheme not only provided a "natural look," but enabled us to make 360-degree pan shots and countless camera setups per day.

In the Control Room of Westworld we utilized a number of "live TV monitors." Original footage that we had shot was transferred to 2” tape for this purpose and the photography was done with Panavision's special "old Bell & Howell threshing machine" which has been equipped with a shutter that eliminates "roll bars." Our shots were arranged in such a manner as to avoid any "looping" of dialogue due to the use of such a noisy camera; for dialogue scenes we simply switched to the Panavision PSR Reflex camera and avoided the TV monitors. Since I had photographed a picture called COLOSSUS for Universal using 17 "live TV monitors" (in color), the problem of setting up the color bars and selecting the proper exposure was really drawn from that prior experience; I did it as before — namely, exposed for 75 foot candles at a stop of T3.2, forcing the development one full stop.

The remaining interior sets on this production posed no particular problems in terms of lighting, with the exception of one set in the castle. Here I had to use three Titan arc lamps because of the tremendous throw involved. On most of my sets, my fill light consisted of "bounce light." The method employed here is quite simple and very effective. I used styrofoam boards (pure white) about 1" thick. The size of these styrofoam boards varied depending on the usage. For example, I had some that measured 48" x 48" and others that were 8' x 8'. These styrofoam sheets can be obtained in 4' x 8' sizes. Since they are featherweight, it's an easy material to use for bounce light. I found that PAR-64 "six-lites" were the most practical light to use for this purpose and they provide maximum control through individual switches in increments of 1,000 watts.

A word about the "Whitney footage." Some of the scenes in Westworld required the Gunslinger's POV, as seen through his "electronic eyes." A chap by the name of John Whitney, Jr. devised an ingenious method of taking original camera footage and converting the image into a fascinating mosaic pattern of varying shapes and colors. The trick here is to provide original camera footage which contains sufficient contrast to produce a good computer facsimile. We made tests of certain key sequences to arrive at a contrast that would be suitable.

For example, we had Richard Benjamin made up completely in white: white make-up, a white western wardrobe, complete with white gloves, and white hair spray. He looked as though he had fallen into a barrel of flour! But that is the kind of contrast that seemed to work best for us on this particular sequence. Other shots (exteriors) were put through the computer to achieve a similar effect. The visual effect really "set up the audience" for a believable robot Gunslinger POV.

On some of my exterior shots I deliberately left the 85 filter off the camera. This is interesting; for years I have heard that you should never shoot "day exterior" without the 85 filter. Well, on Westworld — through sheer necessity — I learned something; you can do it — and successfully. The problem was as follows: We had shot a major sequence (the "shoot-out" reminiscent of High Noon) on an overcast day. The sequence could not be completed on that particular day. The following day turned out to be beautiful — a bright sunshiny day. How do we "match" the missing cuts?

I talked the situation over with Michael Crichton and explained that I had learned from Stanley Kubrick that he had shot A Clockwork Orange entirely without the 85 filter. Moreover, I explained to Michael that if we could shoot our missing cuts after the sun went down — in the flat, shadowless type of light one gets at twilight — we could "match" our overcast day's footage.

To do this meant shooting a little footage each day over a period of a couple of days since the "magic hour" does not last long. However, we were able to “extend the magic hour" by eliminating the 85 filter; we picked up additional exposure in doing so. The MGM lab even gave us "color-corrected dailies" on the scenes that were shot without the 85 filter and I doubt that even the trained camera eye could detect the difference between those scenes shot "with" the 85 filter and those shot "without the 85." Interesting? I thought so at the time and I have since employed this technique on other assignments where daylight scenes normally would be out of the question.

A word about the production staff on Westworld. The rapport between a cameraman and the production staff is no small matter when it comes to creating a "good state of mind." I cannot remember any prior assignment where there was a better rapport between the production staff and myself. The assistant director and unit manager were one and the same person: Claude Binyon, Jr. Although we had never worked together before, it became apparent that Claude was a very knowledgeable person in many areas — particularly, in relating to the needs of the cameraman. He was instrumental in setting up a line of communication — on a day-to-day basis — between the director, the cameraman and the production staff that I have never experienced before. We all worked as a team which, in turn, created a wonderful feeling that eventually rubbed off on everybody. Part of this was due in no small measure to Michael Crichton himself, who seemed to bring out the best in everybody from the floor-sweeper on up! He is the type of director who gets the creative juices flowing. In my case, all of these factors contributed to a "good state of mind."

Aside from being a beautiful example of teamwork at all levels, Westworld — considering its scope — was brought in at the modest cost of $1.25 million in 32 shooting days. A great deal of credit should go to the production designer, Herman Blumenthal for his ingenuity in constructing some enormously gorgeous sets on a shoe-string budget. We had fun making this picture and everybody connected with it felt that it showed up on the screen. Could it be that Westworld is a state of mind for the beholder?

You'll find our interview with writer-director Michael Crichton here. Polito was invited to join the ASC in April of 1981. He passed away at the age of 92 in 2010.