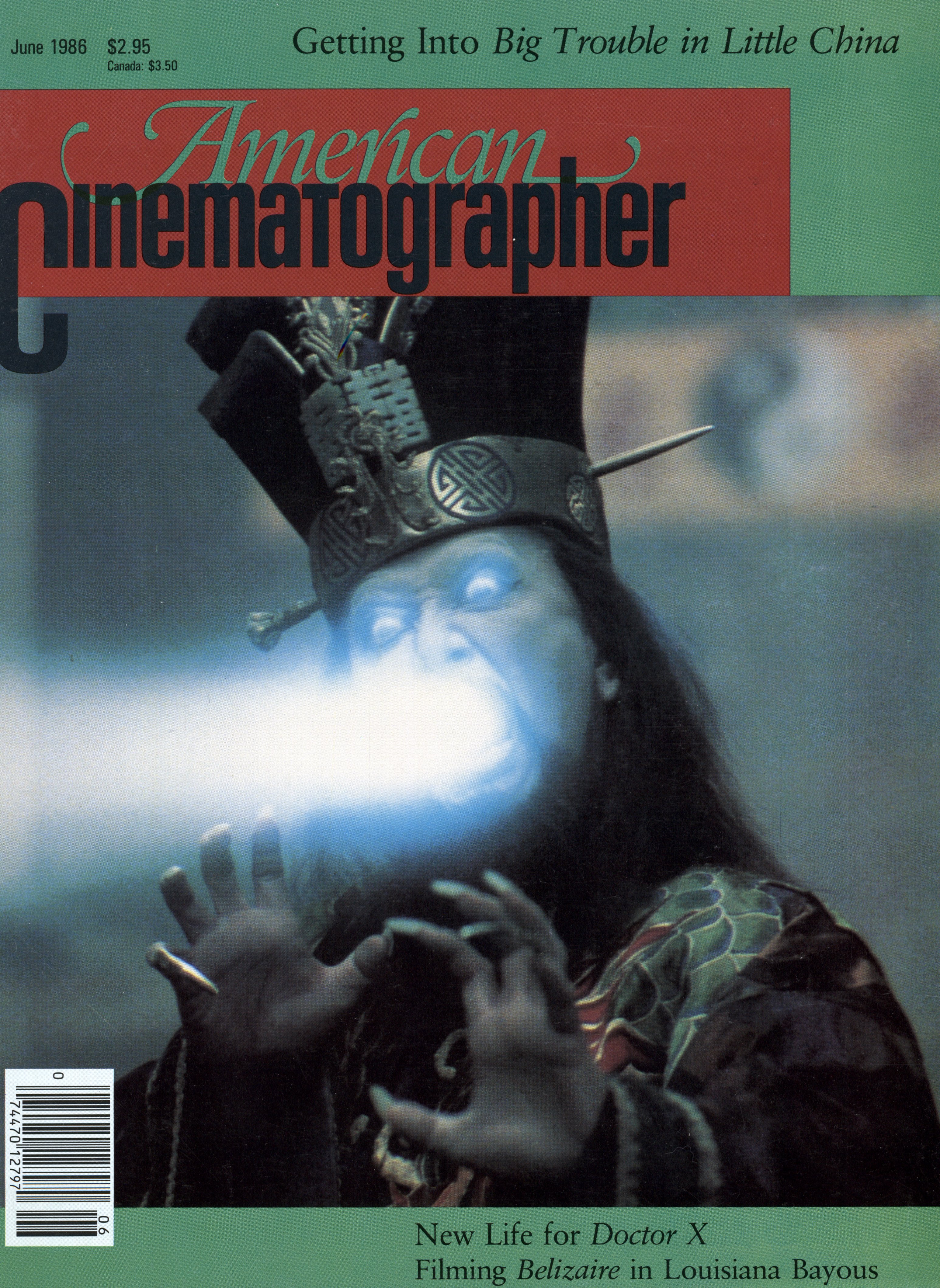

Stirring Up Big Trouble in Little China

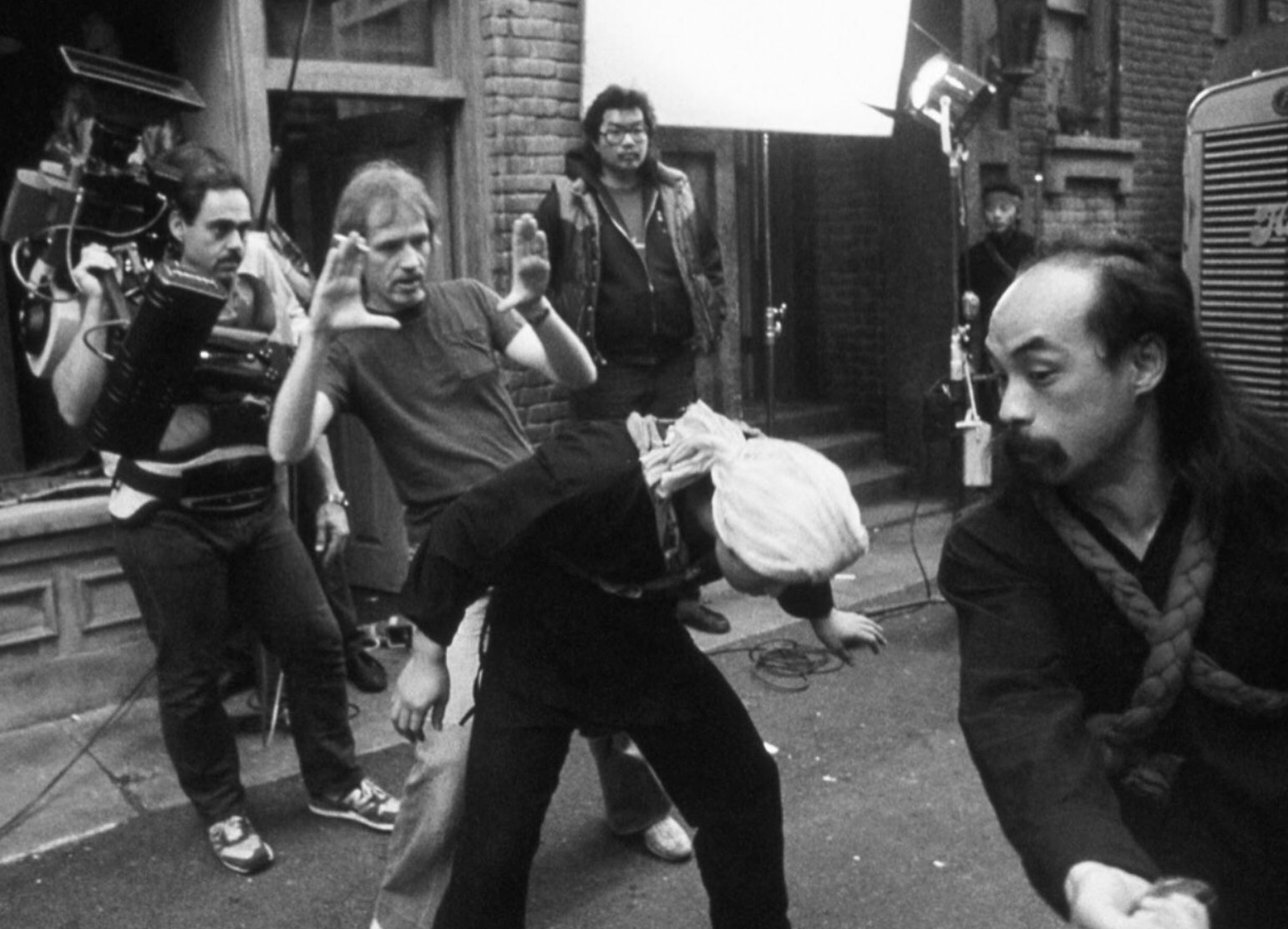

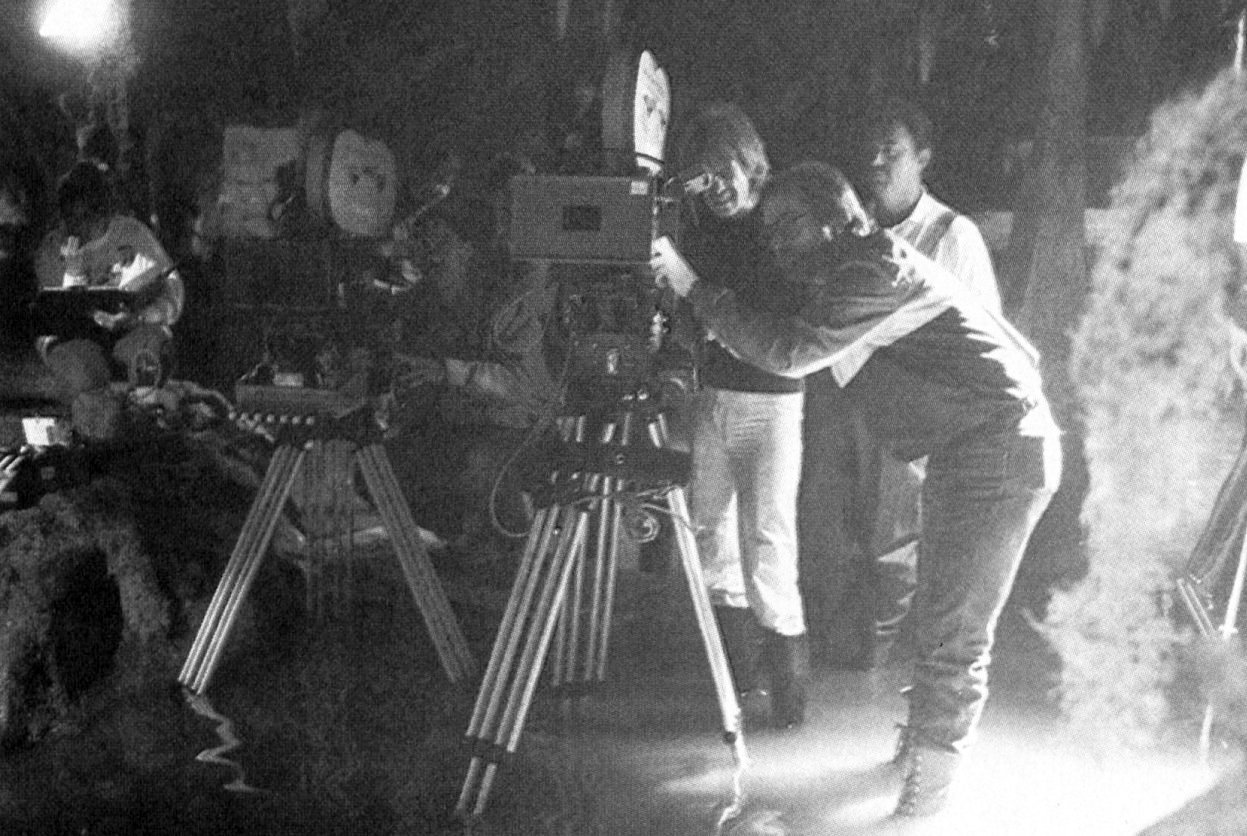

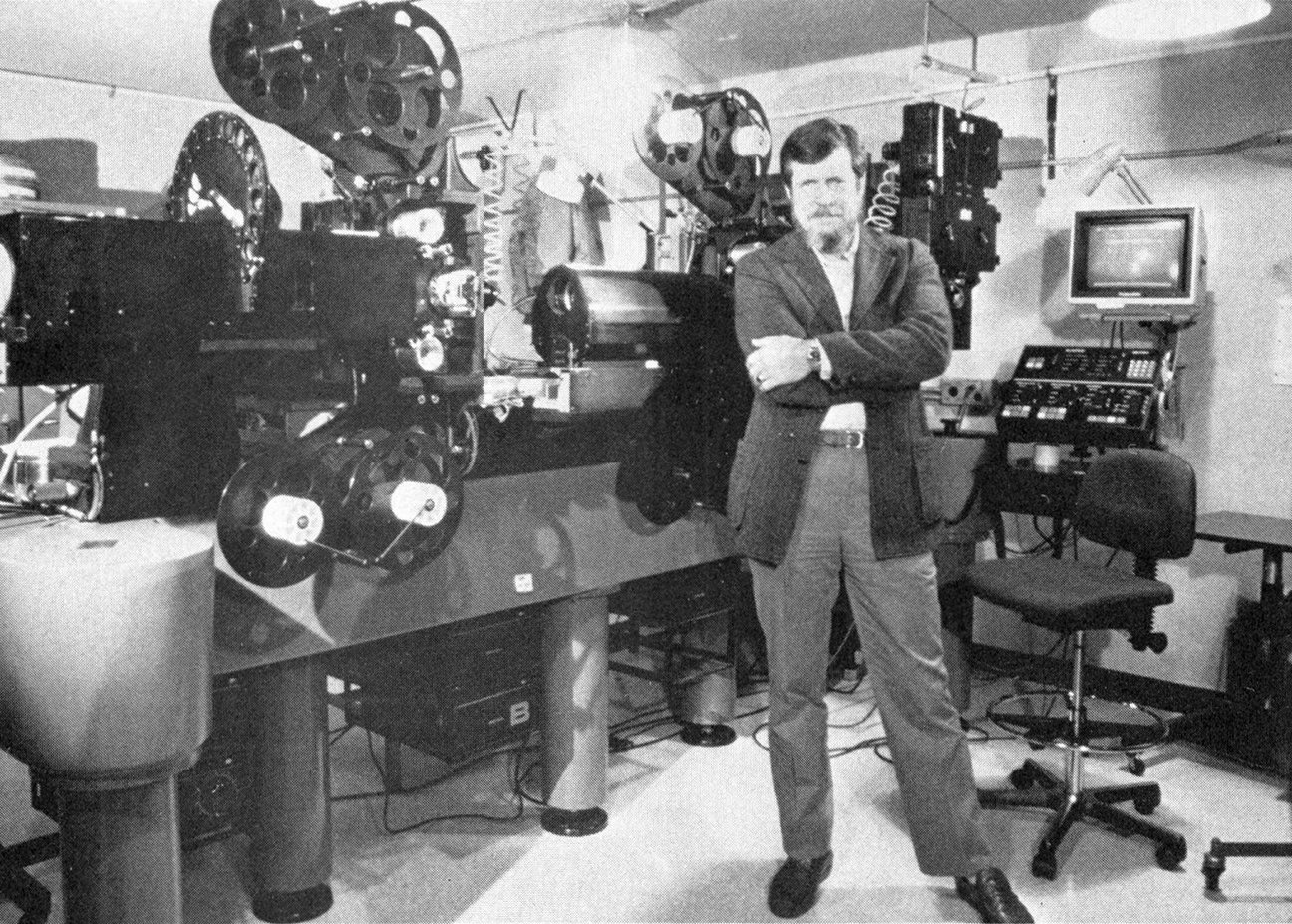

Dean Cundey, ASC elaborates on his seventh pairing with director John Carpenter.

By Mark Steensland

Unit photography by John R. Shannon

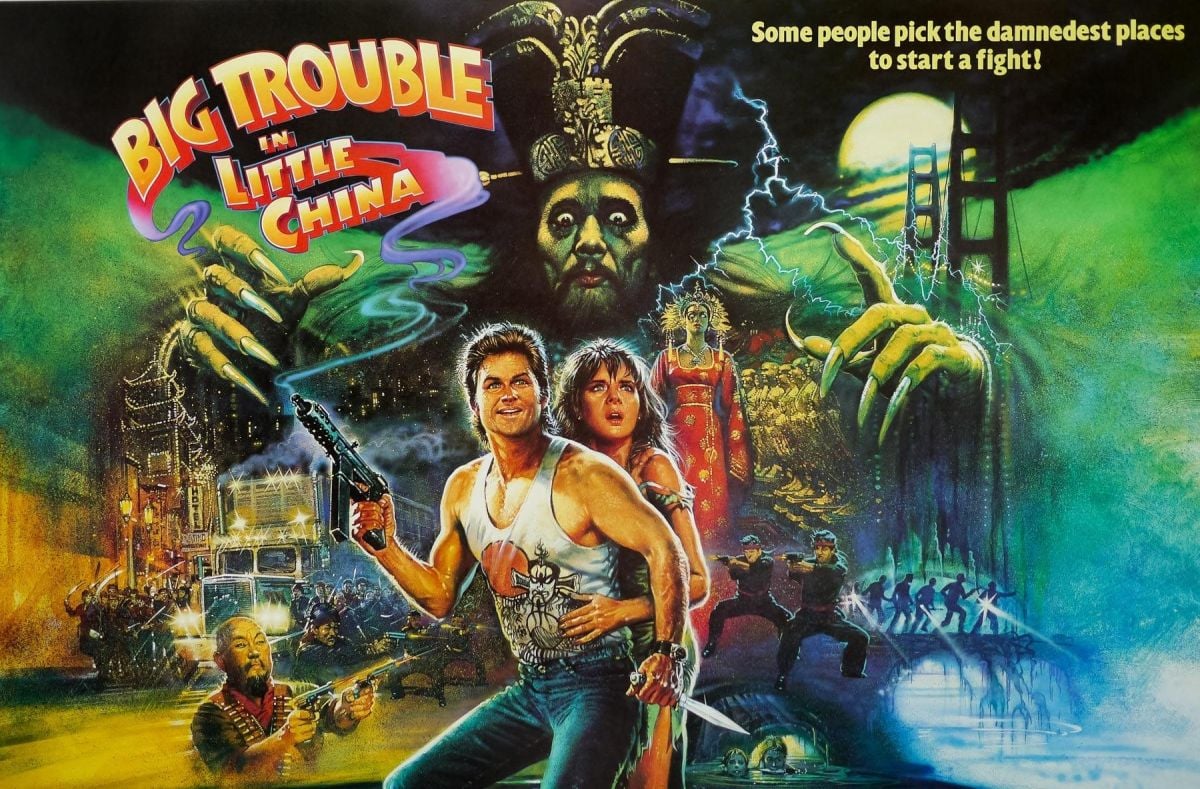

“Big Trouble In Little China has been described as a combination suspense/action/comedy/kung-fu/ghost-story,” says Dean Cundey, ASC, the film’s director of photography, “but, it’s basically an action-adventure picture along the lines of Raiders Of The Lost Ark.”

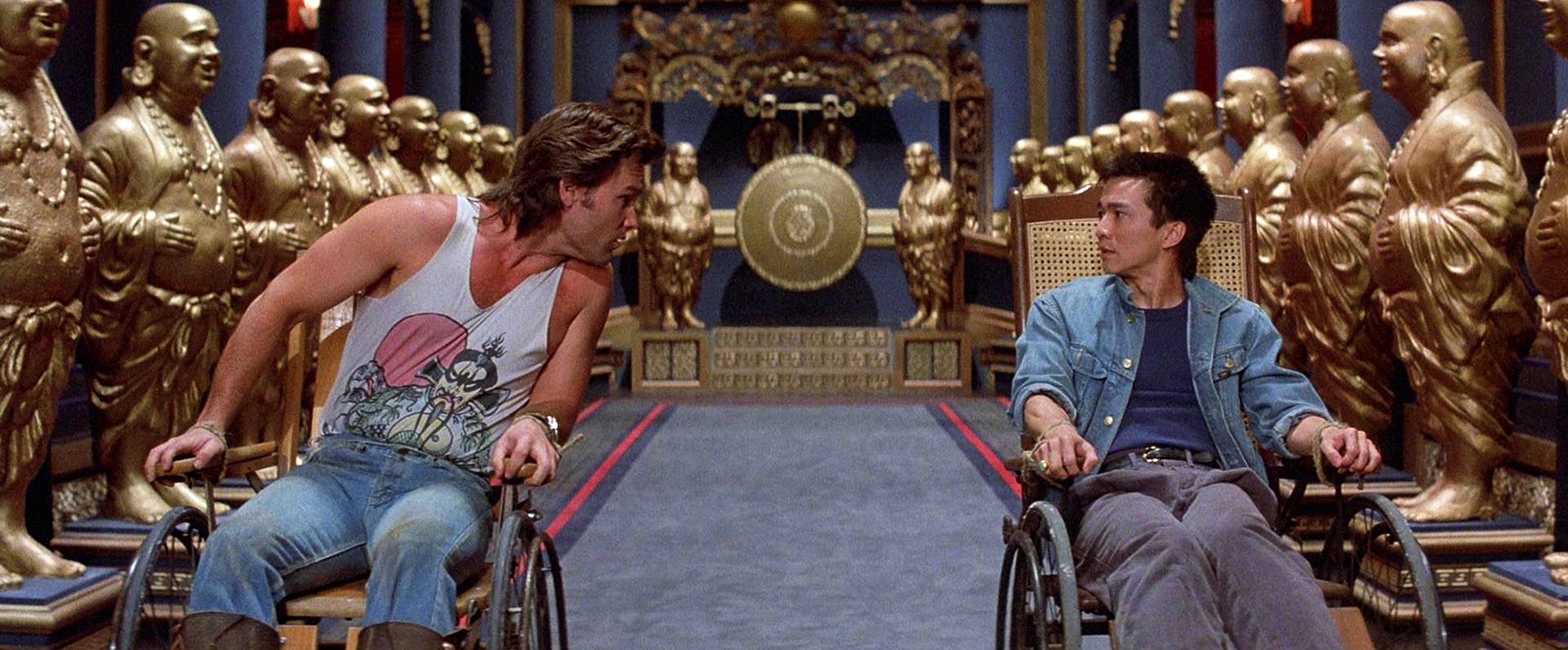

The film tells the story of Jack Burton, played by Kurt Russell, driver of a semi-rig called “The Pork Chop Express,” who uses his truck to haul pigs to the market for slaughter. After winning money from Wang Chi (Dennis Dun), the owner of a restaurant in San Francisco’s Chinatown, in a gambling game, Burton follows him to the airport to collect. Wang Chi is there to pick up his bride, arriving from Peking. Before the two can reach her, she is kidnapped by a vicious Chinese gang, The Lords Of Death.

Burton tries to help Wang Chi find his bride and they soon discover that Lo Pan (James Hong), a 2,258-year-old ghost, has kidnapped the bride because he needs a Chinese female with green eyes in order to appease the gods and return to his human form.

The trail leads Burton and gang underneath Chinatown, into a world where the ghosts live. They encounter a plethora of places — from The Hell of the River of Ashes to The Great Arcade, and the Spirit Path — and a host of characters, from One-Ear and Needles to Thunder, Lightning, Rain, the Door Guards, and the mysterious Flying Eye.

“I guess I’ve always been very visually oriented, always drawing and things like that.”

— Dean Cundey, ASC

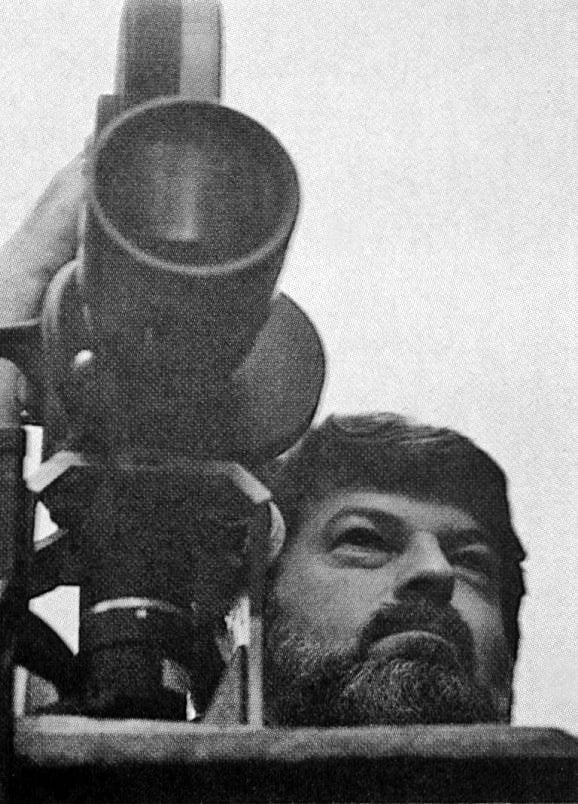

Cundey, who has worked on more than 45 feature films, as well as having photographed almost every film by director John Carpenter since Halloween, describes his job as director of photography as “fulfilling the creative concept of the director and improving or supplying one if there is none.”

In grammar school, Cundey became interested in theater and film when an instructor encouraged him to put on several little plays. Following that, Cundey decided that he was interested in motion picture production design and that he would study architecture in college so he could get into the union. “I guess I’ve always been very visually oriented,” says Cundey, “always drawing and things like that.”

But, while at UCLA film school, Cundey took a class from James Wong Howe, ASC and immediately became interested in the photographic aspect of filmmaking. Says Cundey, “Taking the class made me realize that the cameraman was dynamically involved in creating the visuals. The class was very interesting because we took a simple three-walled set and Howe would then demonstrate how to create mood with only light patterns and contrast ratios.

“His was really the first style that I actually studied because I had the chance to talk with him as well as see his work in the form of dailies. Howe has been attributed with creating a rather naturalistic style to his photography and that is something I try to do with my own work, although bending the laws of nature to create a certain mood is something about photography that I particularly enjoy.” After graduating from UCLA, Cundey was called by several classmates that had convinced Roger Corman to finance their first feature. Having done make-up on several of the students’ shorts, they asked Cundey to do the make-up on their feature.

“I had just graduated and I can remember thinking, ‘Gee, this is great, you graduate from film school and people just call you with work,’” says Cundey. Following the four-week schedule on that picture, he was sitting in his apartment trying to figure out what his next job was when suddenly, the phone rang. “It was Roger Corman,” he muses, “and he wanted me to do make-up on a feature he was directing.”

That film was Gas-s-s (1970). “After that,” Cundey laughs, “I figured I should probably just sit around and wait for calls for photographic work — but they never came.”

Deciding that he would have to do something to dig up work, Cundey set about creating the MovieVan. “I was very intrigued by the Cinemobiles that were being created at the time,” he explains, “and on all of the low-budget features on which I had been working, there was always a scramble to put together a package of equipment from the various rental houses.”

Inspired, Cundey and several of his friends took a Dodge van and modified it with extra doors and interior compartments. They then leased equipment and started renting themselves out to producers as a package deal. “It also gave me the right equipment, which made it easier to do better work.”

Another invention of Cundey’s is the “flicker-box,” or computerized light modulator. “That came about as a result of Escape From New York, says Cundey, “In our discussions of the film, John Carpenter and I realized that there would be very little of the civilized conveniences — namely electricity. We felt that fires would be used mostly and that created a problem for me.

“In the past, in order to create a flicker effect, you had to have someone flickering a dimmer. You can’t really rely on people being able to interpret fire. Although some guys are very good, most of them end up looking like discos, and I knew I would have to flicker large light sources.”

What Cundey required was an electronic device. “With a friend who is an electronics engineer,” he explains, “I sat down and laid out the requirements. We created a device with an electric eye that would read the fire source and then flicker the lights accordingly.” Not only used to interpret fire, Cundey explains that the device also has a computer chip inside that allows it to flicker the light sources to imitate signs and other blinking light sources. “I’ve used it to some effect on almost every show I’ve done,” he says.

Cundey’s first feature as a full director of photography was filmed under the title of The No Mercy Man (1973), although it sometimes shows up on late-night television under the title of Trained To Kill. When the opportunity to photograph Carpenter’s 1978 breakthrough film Halloween came, Cundey had already photographed 18 features.

“The producer of Halloween, Debra Hill, was script supervisor on several of the features I had worked on, as well as script supervisor on Carpenter’s first “real” feature, Assault On Precinct 13,” remembers Cundey, “and when she told me that she and John were doing a feature, she thought that we would make a great team.”

And she was right. That initial teaming was then repeated five times, on The Fog, Escape From New York, The Thing, Halloween II and Halloween III. After a brief hiatus, in which Cundey photographed the box-office blockbusters Romancing The Stone and Back To The Future, the director and cinematographer are once again paired, for making Big Trouble In Little China.

“We had three weeks of pre-production on this film,” says Cundey, “12 weeks of shooting for myself, and four months of post — all to ready the film for a May release.” Although that sounds relatively short for a film of this size (while at 20th Century Fox, the production occupied five stages with a budget of $19 million), Cundey praises the production designer, John Lloyd, with making his job easier. “John is very good,” he says, “and he saved me a lot of the work that I would normally have to do as far as defining the visual look and sources of light on the sets.”

While shooting, Cundey encountered a few problems, although he is quick to announce that no production is without its issues. “That’s one aspect of filmmaking that I find most rewarding,” says Cundey, “and every film carries with it its own set of problems that have to be solved — which I think is a lot of fun.”

“I knew that we couldn’t get the camera in the pipe, maintain the minimum 5' focus plane required for anamorphic, allow the characters to swim by, and pan.”

The first problem was during a sequence in which several of the characters escape down a 3' drain pipe that is half full of water. “The problem,” says Cundey, “was that the characters had to swim into this pipe, stop in the middle where they exchanged some dialogue, and then swim down the rest of the way — while the camera pans with them.” Cundey had just completed a commercial prior to Big Trouble in which he had used a snorkel lens, thus the solution came to him rather quickly.

“I knew that we couldn’t get the camera in the pipe, maintain the minimum 5' focus plane required for anamorphic, allow the characters to swim by, and pan,” he says, “so I had a hole cut in the pipe and we slipped the snorkel down inside. Then I lit through other holes that were covered with grating. This allowed us to shoot from the middle of the pipe and keep the camera out of the way so the characters could swim by and we could pan with them.”

The final shot of the film, which finds Burton driving his truck along a rain-drenched highway at night, created the other problem Cundey encountered. “John wanted to have one long take where we started on Russell’s face in a close-up as he’s driving the truck and talking on his CB radio,” says the cinematographer, “pull back, glide along the side of the truck past his name and everything, to the back of the truck, where the trailer should be.

“We discussed whether or not it would be possible to drive the truck, to light the stretch of road necessary, and to rain the stretch of road necessary. We knew it wouldn’t be, so we decided to use poor-man’s process (shooting on a stage draped in black with lights on fish poles swinging by the stationary vehicle thereby creating the illusion of movement) and we put the truck on a stage and the shot required the flexibility of the Louma crane.” The shot is exactly as it was planned.

Since the film contains extensive optical effects work by Richard Edlund, ASC’s Boss Film Corporation, Cundey took special precautions in the lighting of sets that would be shot by the 65mm optical unit: “One of the things you have to consider when you’re shooting opticals is that it will be a dupe neg. For the best quality, we like to over-expose a half-stop and then print down so that some of the grain and contrast can be eliminated. Since the optical unit uses Hasselblad still lenses on their 65mm camera, which are not as fast as the Panavision lenses, I had to make sure there was enough light.

“Since they have a 170-degree shutter, as opposed to the 200-degree shutter on the Panavision, I knew that they would need another stop of light. So, if I had a T.4 for us, I lit so that the optical unit could have the T.2.8 they needed-providing them with the best negative possible.”

While the introduction of the incredibly fast Kodak 5294 finds most directors of photography shooting their whole film on that stock, Cundey still prefers to use the slower 5247 for some. “I generally use the 94 for interiors and night exteriors,” he says, “and the 47 for day exteriors. I know that some use 94 for day exteriors, but to me, it looks a little funny. The 47 provides me with less grain and the color seems to be less warm and desaturated.”

Rather than rate 5294 at the 320 ASA provided by Kodak, Cundey rates the stock at 500. “Most of the time,” he says, “although when I’m shooting night exteriors, I tend to rate it at about 400 to make sure the blacks are nice and dense. Also, rating it at 400 causes it to print higher on the scale. I think Big Trouble was printing at about 38 — a nice, dense image.”

“They decided it would be easier and quicker, in the long run, to actually build the exteriors on the stage. But trying to make an interior look like an exterior is very difficult since there is no way to light with a one-point source, like the sun.”

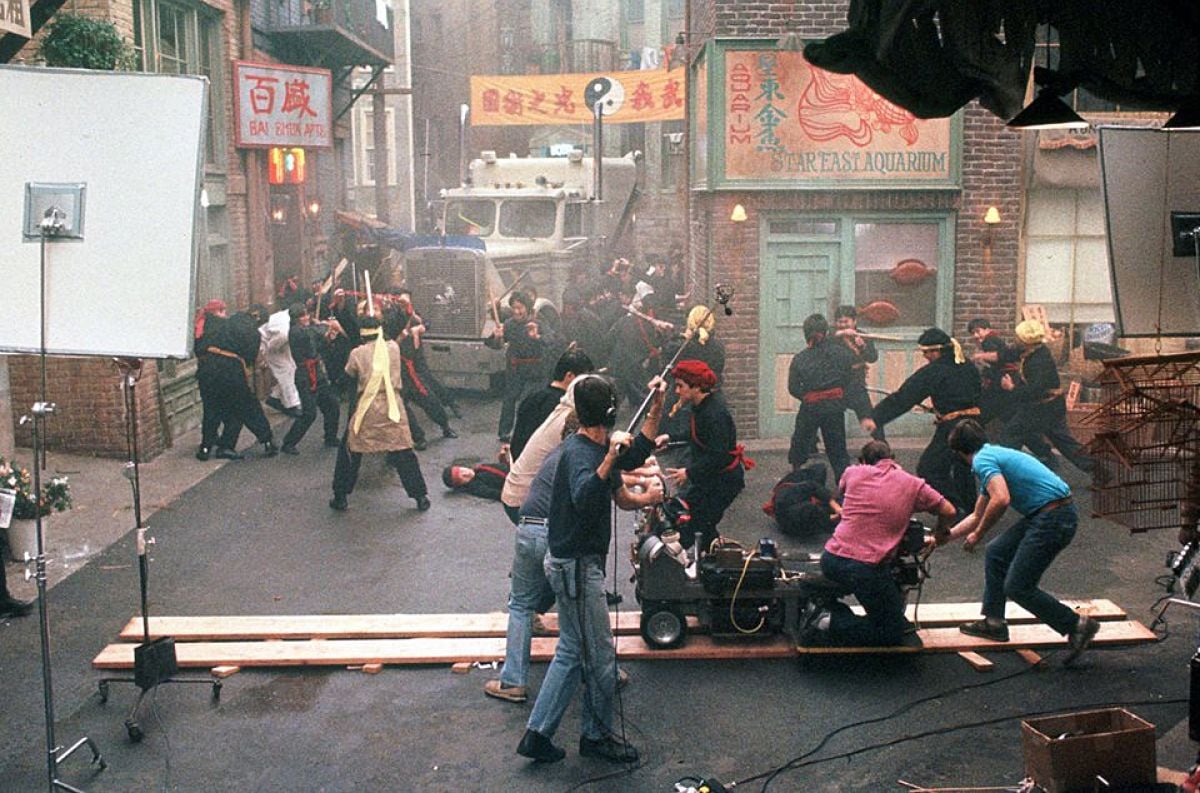

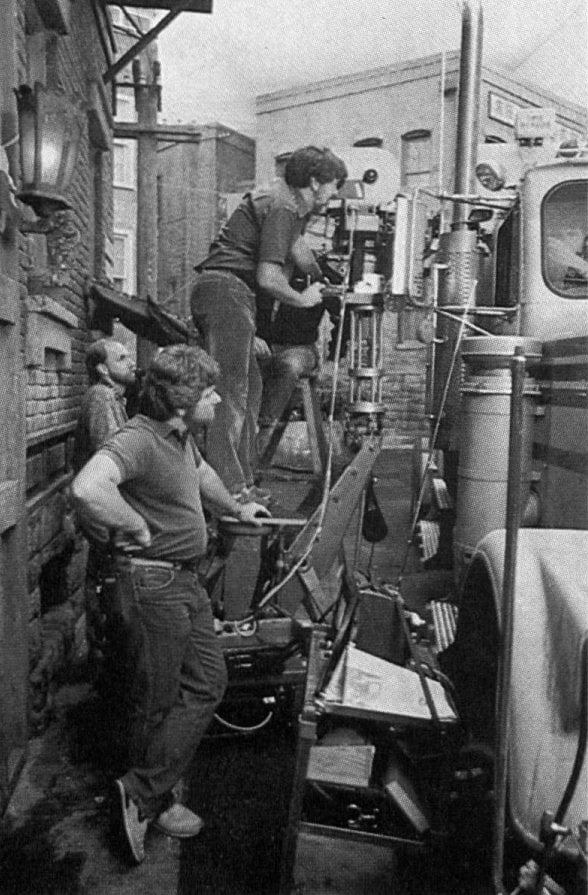

Another problem that Cundey encountered was the staging of an outdoor Tong War fight sequence, involving a massive melee with 75 stunt persons inside on a sound stage at Fox. Originally, the sequence was going to be shot on location in the alleyways and streets of San Francisco’s Chinatown, but after an investigation into the logistics of such a plan, the idea was quickly discarded. “They decided it would be easier and quicker, in the long run, to actually build the exteriors on the stage,” says Cundey, “But trying to make an interior look like an exterior is very difficult since there is no way to light with a one-point source, like the sun.”

The script, however, because it was set in San Francisco, provided Cundey with the beginnings of a solution. “Because San Francisco is a foggy city,” he explains, “my job was easier since I didn’t need to duplicate sunlight — but, rather, the overcast look.” The street set completely covered Stage 6 at 20th Century Fox, and Cundey’s lighting solution was to stretch a silk over the entire stage — about two square blocks.

“We hung coop lights — rectangular units containing about six 1K lamps each — from the top of the stage and then hung the silk below it,” says Cundey. Fifty of the coop lights were hung some 40' above the set. “By the time the light reached the stage,” says Cundey, “it was very soft — almost shadlowless.

“We hung one section of the stage and then I took my meter and read it to make sure that we had a decent F-stop, because one of the things about shooting day exteriors is that you usually have a pretty decent exposure, and if we were at too low a light level, the fact that we were inside would be given away because of the lack of depth of field.” He ended up with a T.4 on the floor and was satisfied enough to have the rest of the stage lit the same way.

Following this, Cundey had the second-unit cinematographer (Steven Poster, ASC) go onto the stage and shoot tests at different angles and exposures. “We found that by underexposing it anywhere from a half-stop to a full stop,” says Cundey, “gave it the suitably gloomy look that we were looking for to create the illusion of a foggy, overcast day.”

To have the whole stage lit in such a way afforded Cundey and Carpenter the ease of moving from setup to setup without having to deal with little more than fill-light for faces, or a little backlight to pick out certain individuals. “It was handy,” says the cinematographer, “because we were dealing with large action sequences where you don’t want to take time to intricately create a setup.”

“One thing that I would like to fool around with, if the same situation ever arises,” says Cundey, “is something we discovered while we were shooting the tests. We were always afraid of tilting up and seeing the silk, but we found that when we did tilt up and we were a little overexposed, the silk looked like a white sky. We mounted remote fog units along the top of the buildings and had them squirt fog on intervals so that it would hang along the silk, and the few times that we do tilt up, it looks like clouds, fog, and a realistic white sky.” With all of the elements carefully combined and choreographed, the illusion of being outside on a San Francisco street is perfected.

“One of the things that I like to do,” says Cundey, “is give each scene some kind of contrast with either the scene before or the scene after so that you’re not always looking at the same kind of ‘look.’

“The great thing about the script was that it had this almost built-in. One moment, we would be in an area that was lit high-key, and then we would go into an area that was very low-key with fire as the light source and smoke for effect.

“One thing I like to do a lot of is place the light source within the frame because I feel it sort of ‘explains’ the lighting.”

“One thing I like to do a lot of is place the light source within the frame because I feel it sort of ‘explains’ the lighting. I think it is a good way to get light into a tricky area by placing, say, a lamp on a table. It saves you from having to do a lot of artificial lighting, and the lamp obviously looks more realistic than anything you can do.”

“I used to shoot the whole script in my head as I read it,” Cundey claims, “but I don’t do that anymore. I found that, very often, what I had conceived in my head was different from the director and I have always thought that the director has the last word on a film.

“I find that one of the most enjoyable things about filmmaking is that each film is a different experience. You’re dealing with a different director, different actors, and different production designers, and it’s rare that all of those elements are duplicated.

“I don’t feel any particular loyalty to the director or producer. My job is to serve the film and provide everyone involved with more than is required by budget or time limitations.”

When asked what his best work as a cinematographer is, Cundey is quick to reply: “I always like to consider my next one as my best, although The Thing and Escape From New York have some of the visual elements I most enjoy doing.

“I was also very pleased with the way Back To The Future came out. The idea of creating two eras and subtly altering each one photographically to create those times for the audience was very exciting.”

Only days after wrapping Big Trouble In Little China, Cundey crossed the Fox lot and started shooting Project X, starring Matthew Broderick. “It’s about a guy in the airforce who dreams of being a fighter pilot,” explains Cundey, “and one day, he is assigned to Project X, which he thinks is the training program for fighter pilots, but he soon finds out otherwise.

“I never turned down a project in the early days, because I always knew that each project would afford me the opportunity to experiment with someone else’s footage and solve problems and learn. Photography allows me to move the audience with the visuals, and that’s what I like doing best.”

Cundey would go on to shoot such complex feature films as Who Framed Roger Rabbit, Jurassic Park, Apollo 13 and many more. He was honored with the ASC Lifetime Achievement Award in 2014, which was presented to him by longtime collaborator and friend John Carpenter.

If you enjoy archival and retrospective articles on classic and influential films, you'll find more AC historical coverage here.