Cameras in Shooting War: AC in the 1940s

The tumult of the decade was reflected in the pages of American Cinematographer as the global conflict of World War II called for total motion-picture coverage.

Editor’s Note: This is an expanded version of the feature story that appears in the March 2020 edition of AC. Some images are additional or alternate.

The ASC has never been an overtly political body, with its flagship publication focused on artistry rather than activism. However, in December 1941, America’s abrupt formal entry into World War II put the country on a new footing. ASC members were among those who reported for duty, and AC began detailing how cinematographers could contribute — and were contributing — to the war effort.

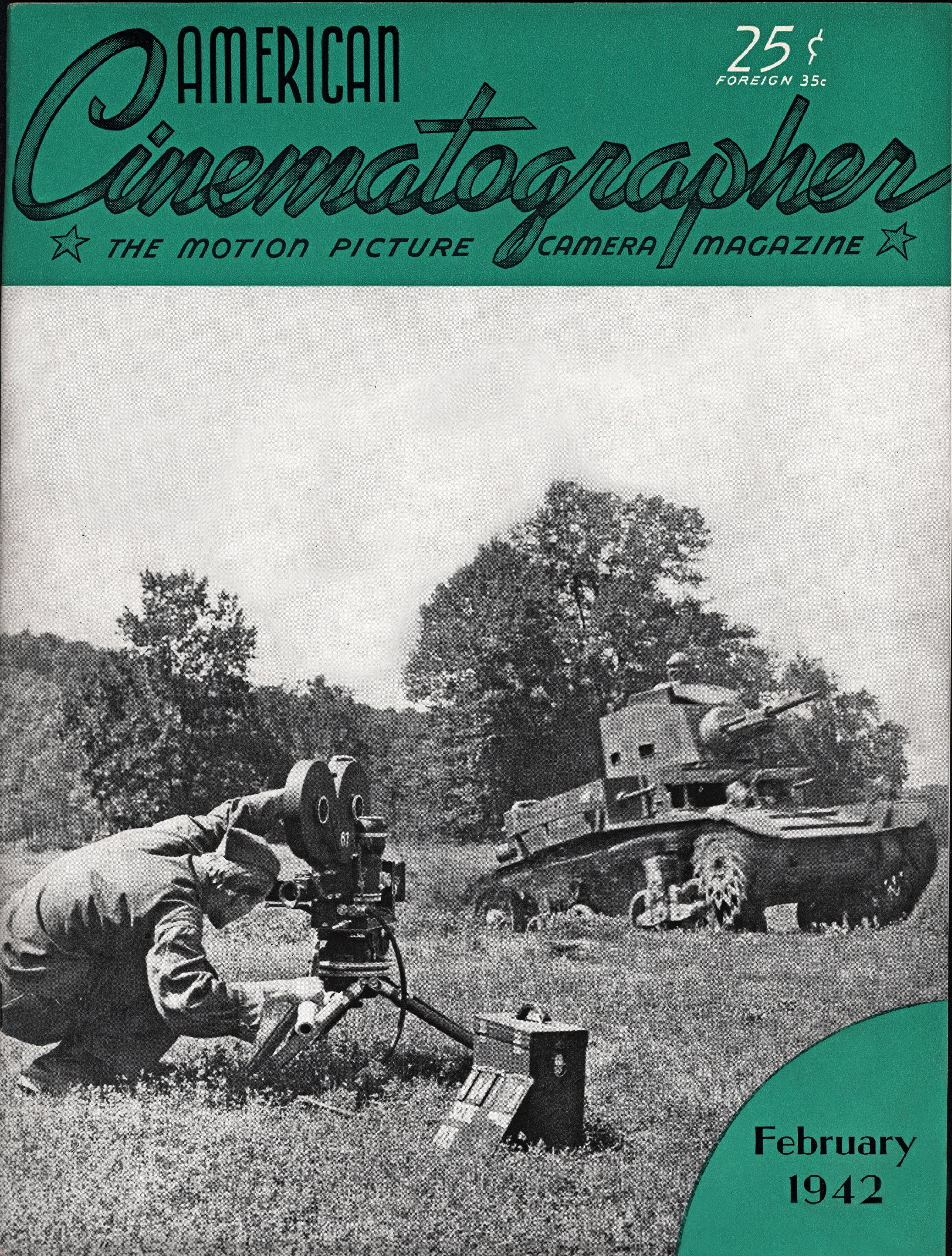

This change is graphically represented by the magazine’s February 1942 issue, the cover featuring a U.S. Army cameraperson setting up a shot on an M2 light tank, presumably for a training film:

While AC had long reported on how the U.S. military exploited motion pictures for training, tests and propaganda purposes, such stories were relatively rare, and generally buried on the inside pages. AC’s previous cover images featured such Hollywood studio feature films as Lydia, Steel Against the Sky and To Be Or Not to Be. So one can imagine the reaction of subscribers receiving the February issue and seeing this U.S. Army Signal Corps photo on the cover. But then, it was the first issue of AC to be completed and printed after the Pearl Harbor attack of December 7 that drew the country into full-scale conflict.

Perusing the pages of AC in 1940, however, one would hardly have known large parts of the world were already ablaze. The magazine focused on new technical refinements, including improved silent cameras, anti-reflective coatings to make lenses faster, and the effects of “lantisification” to increase the speed of film stocks. Other coverage was not focused primarily on Hollywood studio features, but rather on travelogue films shot in Canada, Mexico and South America, India, the isles of the Caribbean, the scenic U.S. National Parks and territory of Alaska, and even the Arctic. Stories on amateur cinematography — 16mm and 8mm — also dominated the pages, with numerous tutorials on lighting for Kodachrome, as well DIY projects for professional-inspired filmmaking gear.

Little was said openly about the war already going on in Europe and Asia, though its effects were being felt by the U.S. motion picture industry, as reported in oblique ways. For instance, a March 1940 story that in 1939, Brazil usurped the United Kingdom as the largest consumer of positive and negative motion-picture film stocks — part of a 15% drop in sales worldwide. Outside of the Americas, less time and resources could be spent on movies, and the U.K. had nearly a drop of 50%. No direct mention as to why, but presumably impending attack by German forces that had already crushed Poland and were threatening Belgium and France.

War news was also being openly suppressed. A story in the January 1940 issue of AC noted that filmmaker Julien Brian brought graphic footage of the German Luftwaffe bombardment of Warsaw to be screened at the Shrine Auditorium in Los Angeles under the auspices of the Pacific Geographic Society. However, “Requests had been made that he refrain from showing any scenes of bombings, any scenes of war. So he did not. Nevertheless the films exist. They are on the record, for today and tomorrow. It is quite probable the squeamish persons requesting their non-projection would have found an ardent supporter in that inaction or non-action in the person of the German Government’s consul general in San Francisco. Or among any other Nazi sympathizers.”

Noted in April of 1940: “Consul Alan Steyne, London, reports the British motion picture industry is concentrating to a greater degree than formerly on the production of feature films suitable for international distribution. Present indications are that providing no serious air attacks occur and personnel problems do not become too difficult, production in British studios will be well maintained during the current year.”

By July of 1940, the German Luftwaffe was bombing England on an almost daily basis, initiating the Battle of Britain.

That same month, AC reported news from Asia: “[Filmmaker] Porter D. Dilley is in Los Angeles after two years in China with his camera and 25,000 feet of 16mm film. China at Bay is the title selected for 1,800 feet of the total. This part was taken in the South of China. A little over half the time he was with the Japanese army, in Manchuria or North China. With the troops of that nation, his journeys covered 12,000 miles. Instead of handling the usual material of war films such as showing that of highranking officers, masses of marching troops and columns of mechanized equipment, this film vividly portrays the defense efforts of the local population. In those portions of ‘free’ China which are unable to receive protection of the central forces, these groups shoulder the burden of defense, using whatever resources they may have at hand.”

The caption to a photo of a makeshift Chinese munitions factory staffed with young girls reads: “Note the unexploded shells [stored] under the tables. These were shot into this area by the Japanese. The shells which do not explode are gathered by the Chinese, broken apart with hammer and chisel, and the materials used to make hand grenades.”

The war in Asia was revisited in December, as Rey Scott, cameraperson/explorer, returned to the U.S. with nearly 10,000' of Kodachrome 16mm footage he’d shot in China, including the Japanese attack on Chungking: “The bombing covered two days. It is said Japan had announced the city would be bombed for seven straight days. It is believed that at the end of the two days, there may not have been enough buildings standing to justify a third 1,000-mile trip. The bombing beggars description. At the time the city was raided, the population was 240,000. Nearly 200 planes appeared on the first day and 170 on the second. You see the flash of the bombs and the slow following of the flame, which gradually grows…”

“This war, it becomes increasingly evident, is going to be fought almost as much with cameras as with guns...”

In September 1940, the story “Uncle Sam Seeks Camera And Laboratory Men” revealed that the U.S. was gearing up for war: “The United States Civil Service Commission has announced open competitive examinations to secure motion-picture photographers and technicians for Government service. Applicants must have had broad, progressive, and responsible full-time paid experience in high-grade motion-picture photographic work as cameraman, photographer from a plane in flight, or in film processing and laboratory work, the responsibility assumed varying with the grade of the position.”

Meanwhile, AC continued to cover Hollywood productions, with Society members often writing articles. “Realism for Citizen Kane,” written by Gregg Toland, ASC, was published in February 1941. One month later, Arthur C. Miller, ASC wrote “Putting Naturalness Into Modern Interior Lighting,” detailing his work on The Mark of Zorro and Brigham Young.

But when Pearl Harbor was attacked on December 7, 1941, everything changed, and AC editor William Stull, ASC made his first story assignments for a new era: “Movies Speed Training of R.C.A.F. Fighting Airmen,” “Motion Pictures in the Army,” “Roy Kellino Films England’s War Effort” and “Amateurs Make Defense Films!”

AC’s new editorial angle remained throughout the war, and even coverage on Hollywood productions favored war pictures, including cover stories on To the Shores of Tripoli, Wake Island, The Commandos Strike at Dawn and Air Force in 1942 alone.

Immediately after Pearl Harbor, ASC members enlisted either to serve from behind their cameras or to train new talents to do the job. Meanwhile, the government’s rationing of materials such as steel, wood and aluminum forced working cinematographers to do more with less. “If America is to serve, as the President has pledged it must, as the arsenal of the Democracies, every scrap of steel must do its bit,” noted AC editor Stull. “Most of it must go to the task of making guns and tanks and planes and ships with which to smother the resistance of the enemy. What little remains for essential civilian uses must be made to do its work as long and as thoroughly as possible, or replaced by some non-strategic substitute.”

To mask shopworn or partial sets, cinematographers often had to employ deep shadows and expressive lighting, and it has been suggested that the resulting stylistics contributed to what the French would later dub “film noir.”

Stull later noted, “Recent trade-paper headlines indicate that the major studios are considering, as a wartime move to conserve film, electrical power, chemicals, time, effort and money, the adoption of a rule whereby production units would be restricted to a maximum of three ‘takes’ of any given scene.” This did not come down as Federal edict, but studio bean counters may have liked the idea.

One of the ASC members who immediately volunteered was Toland, who served as a Navy lieutenant until the end of the war, working closely with USNR Comm. John Ford, for whom he had shot The Long Voyage Home and The Grapes of Wrath. They served within the Office of Strategic Services, a predecessor to the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). Toland and Ford co-directed the 1943 propaganda film December 7th: The Movie, for which they won an Academy Award. Toland later spent much of the war in South America mentoring local filmmakers and promoting U.S. interests on that continent.

This brief U.S. war bonds promotional short was shot by Toland and directed by Alfred Hitchcock:

Meanwhile, more first-person accounts from the front lines were published, including “A Russian Cinematographer Films the Battle for Moscow.” Author Feodor Bunimovich wrote, “At headquarters we were told that a trench mortar battery ... had fired 80 projectiles during the day, destroying two enemy machine-gun nests, two dugouts and a large number of men. The battery was silent. I informed the commander over the telephone that motion-picture cameramen were visiting the battery. ‘Wait a bit,’ he replied. ‘We will establish the enemy position in a moment and then we will be ready to welcome you.’ A little while later the order came for the battery to open fire.”

In the February 1943 story “From a Nazi Prison-Camp to a Signal Corps Camera,” freelance writer Charles Sweeny reports, “Two-and-a-half years ago, I was a prisoner in a Nazi prison camp in France. Today I’m in Hollywood, waiting [for] a call to active service in the Signal Corps of the U.S. Army. And I hope I draw an assignment to active combat camerawork in the field, for I’ve a score to settle with those Nazis for some of the things I experienced myself.”

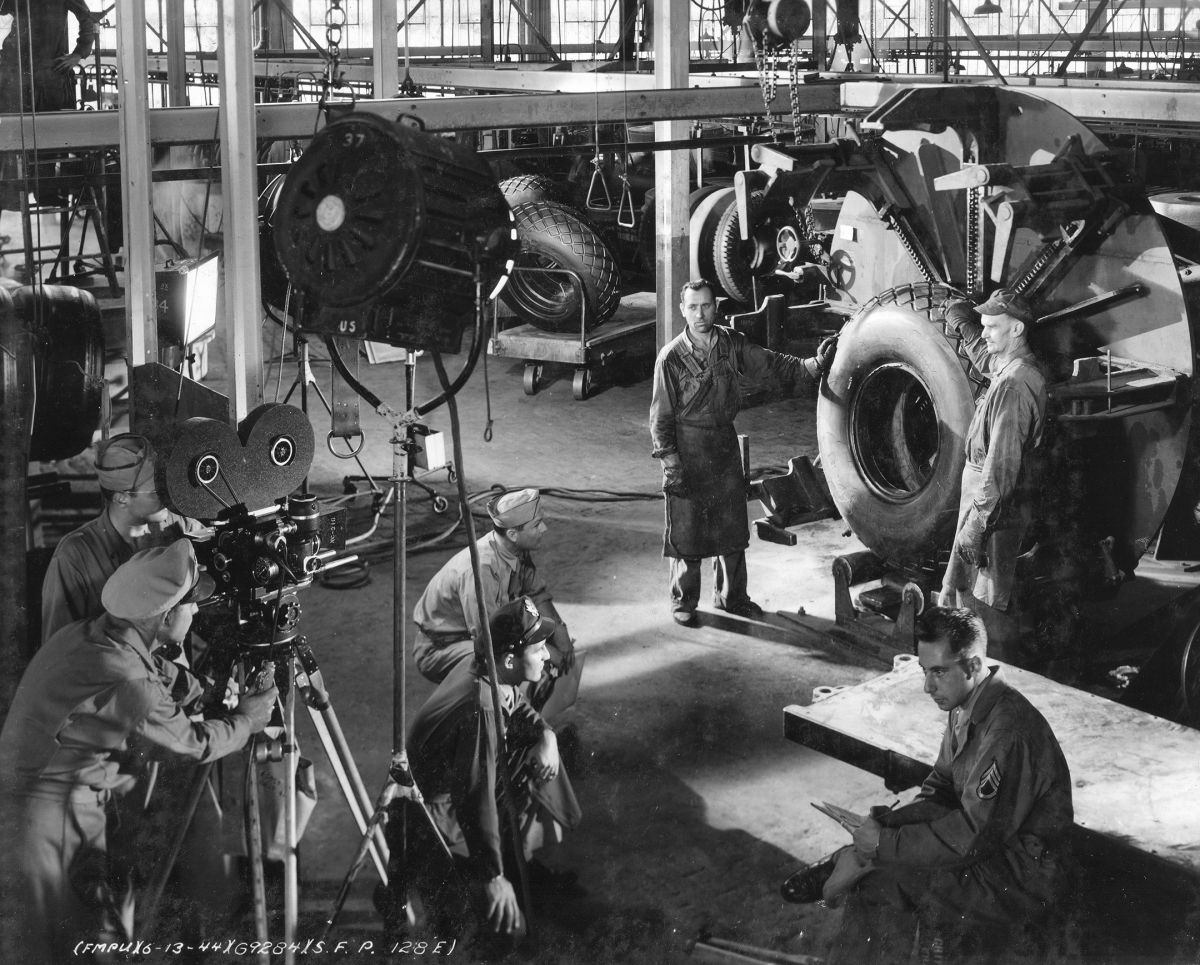

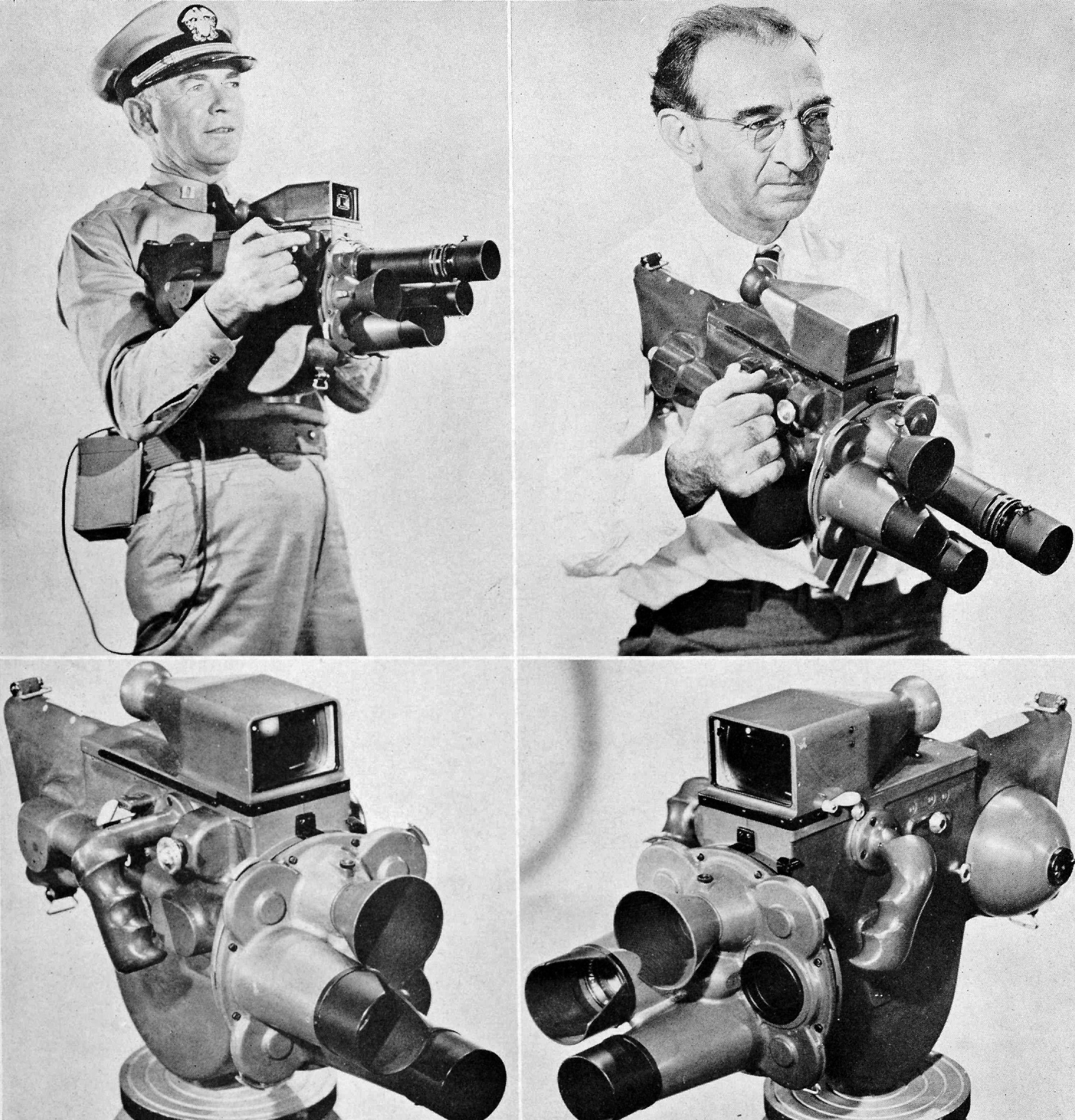

The war also started innovation and invention, exemplified by the introduction of the Cunningham Combat Camera, a new motion-picture unit designed by Harry Cunningham for soldiers, as detailed in AC November of 1942. “This war, it becomes increasingly evident, is going to be fought almost as much with cameras as with guns,” editor Stull stated before extoling the virtues of the Cunningham. “Already, the U. S. Army, Navy, Air Force and Marine Corps have put hundreds of cinematographers into the field to bring back a living record of this global war. By the time our forces grow to their full strength, the number of these combat cameramen may well run into the thousands. Their cameras will bring back actual records of front-line operations on land, at sea and in the air; some for purely tactical and technological study, and some as documentary film reports to the American public.”

American Cinematographer itself was seen as an asset for the military. In September of 1942, Stull noted: “One of the finest compliments this magazine has ever received came to us recently from the Visual Aids Director of one of our largest and most important Army Service Commands. In his letter he told us American Cinematographer is ‘being used to good advantage at this headquarters in the training of men who will operate training-film libraries within this command.’ By way of confirmation he enclosed a copy of a memorandum issued to the men he was training, urging them to read specified articles in American Cinematographer. From the first seven issues of this magazine for the current year, no less than 21 articles were listed as being helpful to these men in the Army’s visual education service. Five of them were indicated as compulsory reading material, with the statement that questions based upon them would be included in the Final Examinations for the course.”

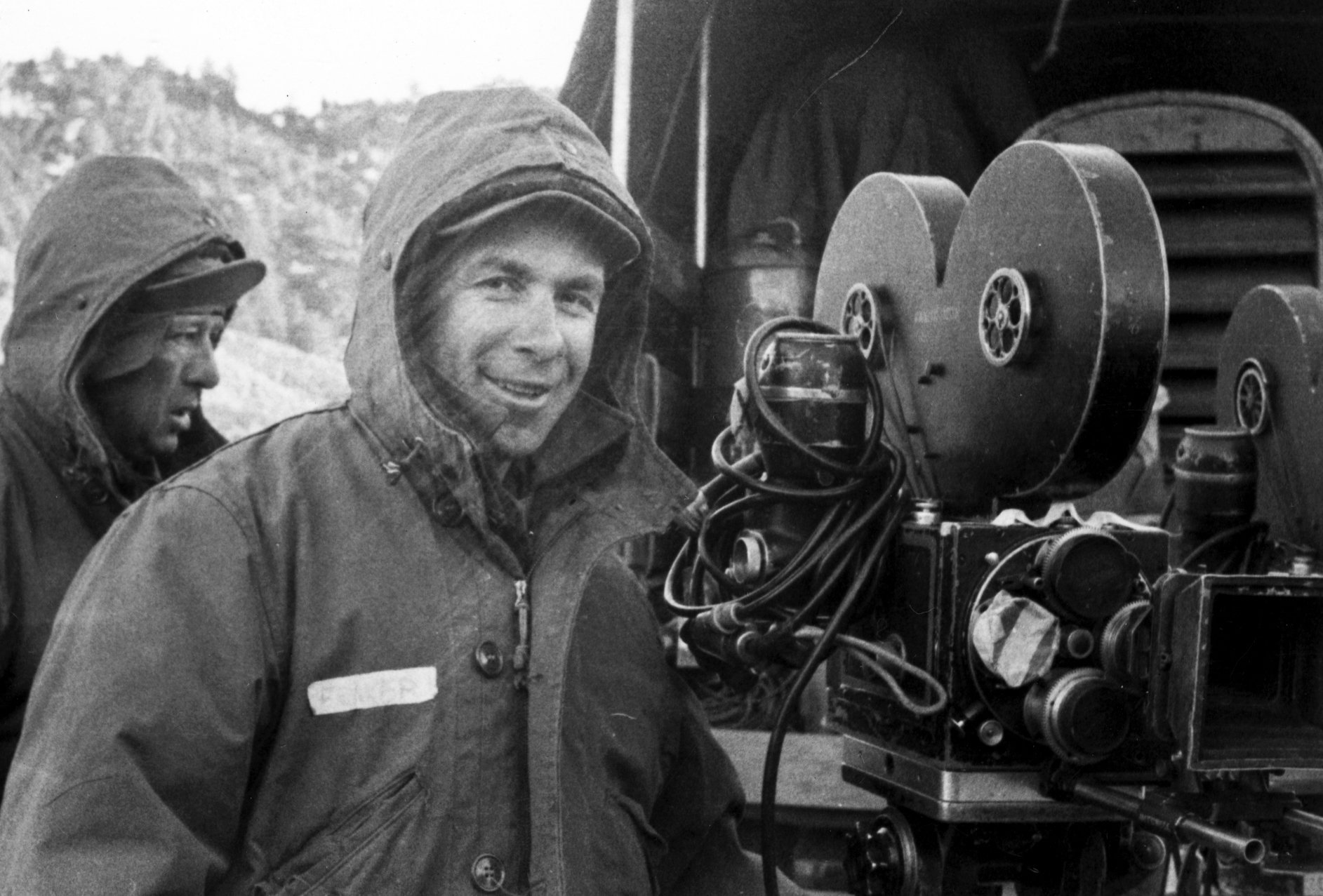

In October 1945, U.S. Army Sgt. Herb A. Lightman, a combat cinematographer of the 167th Signal Photo Co., wrote, “Our record spoke for itself. The 167th had participated in four major battle campaigns, shot footage during a period of 250 consecutive combat days, and had been presented with the Meritorious Service Award.” Lightman had survived the war, and gave thanks to ASC members who helped train him to do his job, including John Arnold and Emery Huse. After becoming a regular contributor to AC, Lightman would serve as the magazine’s editor from 1966-1982.

It’s no surprise that World War II, the pivotal event of the 1940s — perhaps the century — would have such an impact on the pages of American Cinematographer. And those interested in the conflict’s history would do well to include the ASC’s magazine of record in their studies, especially as it’s the immense motion-picture record of its many key events — from Pearl Harbor to the D-Day landing to the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki — that keeps its harsh lessons in mind even today.

As Stull correctly predicted in AC March of 1942, “When peace is at last restored at the end of this war, historians and dramatists alike are going to find a rich treasure in the billions of feet of motion-picture film which are chronicling every phase of both sides of the conflict.”

Additional research by Stephen Pizzello.

ASC MEMBERS IN SERVICE

(A partial list from AC Dec. 1942)

John Alton (Army)

Arthur Arling (Navy)

Joseph August (Navy)

Wilfred Cline (Air Force)

Stanley Cortez (Army)

Floyd Crosby (Air Force)

Philip M. Chancellor (Navy)

Wilfred Cline (Navy)

William Dietz (Navy)

Harry Davis (Navy)

Ray Fernstrom (Army)

Henry Freulich (Marine Corps)

A.L. Gilks (Navy)

Sol Halprin (Navy)

Reed N. Haythorne (Navy)

Charles W. Herbert (Army)

John Hickson (Army)

Harry Jackson (Navy)

Lloyd Knechtel (Army)

Art Lloyd (Army)

Fred Mandl (Army)

Peverell Marley (Army)

Allen Siegler (Navy)

William V. Skall (Air Force)

Clifford Stine (Air Force)

Gregg Toland (Navy)

Paul Vogel (Army)

Joseph Valentine (Army)

Harold Wenstrom (Navy)

Al Wetzel (Army)

Gilbert Warrenton (Air Force)

You’ll find more decades of AC coverage here.

For access to 100 years of American Cinematographer reporting, including every issue mentioned in this story, subscribers can visit the AC Archive. Not a subscriber? Do it today.