Ridley Scott: “I’m Not Doing Radio Plays, I’m Making Cinema”

The director comments on Napoleon and his longtime collaboration with cinematographer Dariusz Wolski, ASC.

American Cinematographer: What inspired you to make a film about Napoleon?

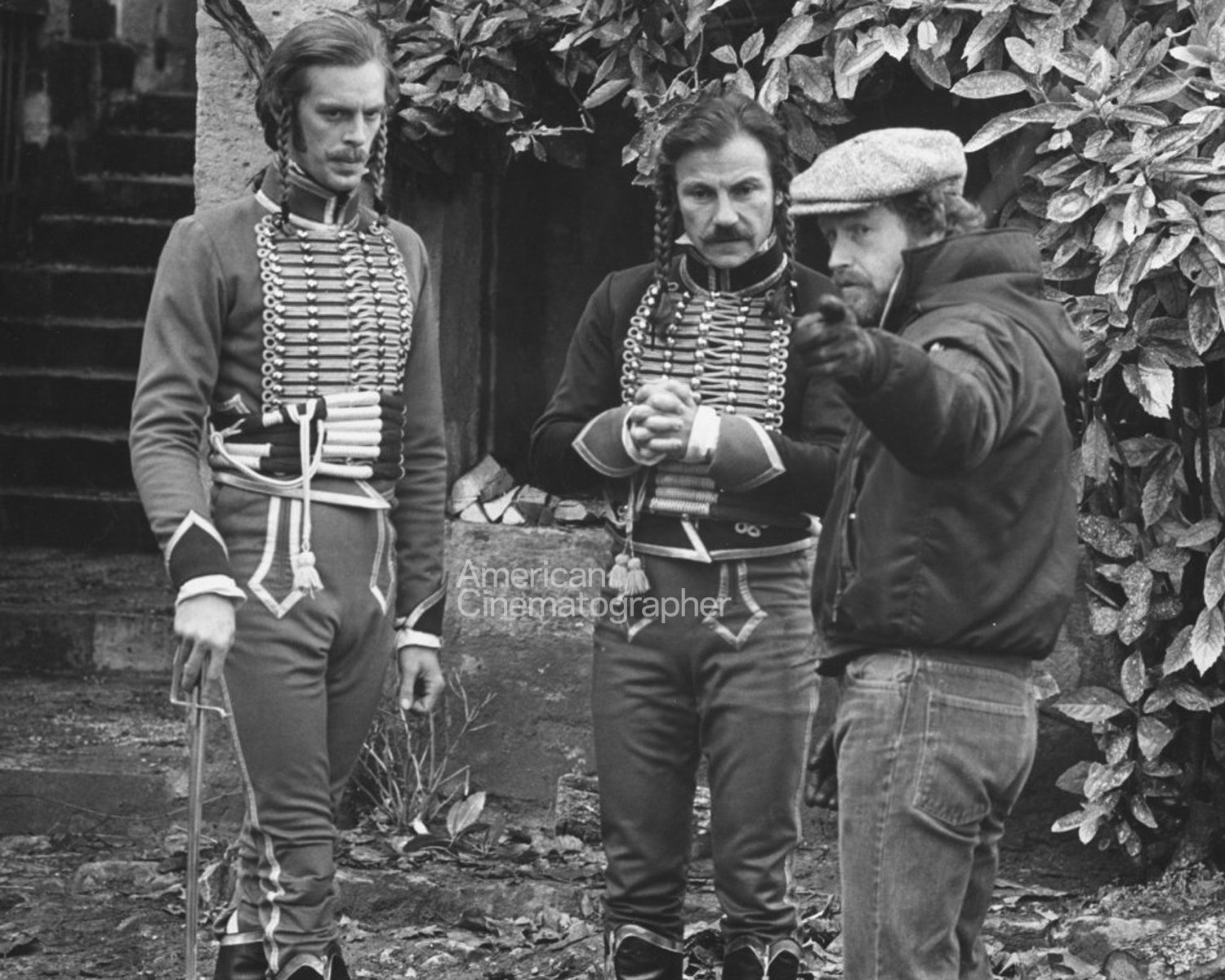

Ridley Scott: I was a very successful commercial director. I had a good office in Paris, and from that, I really got to feel and enjoy the French culture: their food, their restaurants, the importance of wine. Almost by accident, I discovered a short book, a 100-page novella called The Duellists, about two soldiers in Napoleon’s army, which I turned into a movie [photographed by Frank Tidy, BSC]. In that film you have a working-class Harvey Keitel, and Keith Carradine, who is playing upper class. So, you have a clash of cultures, a clash of class in the same army. Napoleon brought this about: He put together the two classes because he figured he needed them both. The film ends on an image of Harvey Keitel — except to me, Harvey Keitel was the shape and dream of Napoleon Bonaparte.

“I’m a director who’s very conscious of his budget and very respectful of anyone who is crazy enough to give me money to make a movie.”

— Ridley Scott

Jump many years on, and I had done Gladiator and had a good experience with Joaquin [Phoenix]. I’m shooting a film called The Last Duel and I’m two kilometers from where I shot the calvary charge in The Duellists. And it all suddenly tumbled back. I’m not saying we wrote the script fast, but The Duellists was an endorsement to me that we already had a roughed-out version of Napoleon, though I couldn’t quite get there. This pushed the new film home.

Dariusz Wolski, ASC mentioned that Abel Gance’s Napoléon was an influence, and that you nearly included a version of that film’s memorable snowball fight in your film.

Abel Gance was a spectacular art director. I was going to start on the snowball fight, [but] then everyone said, ‘Everyone’s seen Abel Gance’s movie.’ I said, ‘No, they haven’t. It’s a four-hour number, and not everyone wants to sit through four hours.’ As to not including the snowball fight, I don’t regret it — except that when you make a film, you always think, ‘Maybe I should have put that in.’ I’d even storyboarded the fight, which [involved] cadets in a snowy quadrangle. The younger cadets are being brutally pounded by the older cadets, while behind a column is a small cadet making snowballs. What’s interesting is he’s putting stones into each snowball. He flings one, strikes the older cadet on the head and there is blood. You cut, [and] they’re in an office standing on a mat before the commandant. ‘What is your name, boy?’ The boy says, ‘Napoleon, sir.’ ‘Your second name?’ ‘Bonaparte.’ That was the beginning of the movie.

That sounds like a terrific scene. Did you film it?

No, no, no, I’m a director who’s very conscious of his budget and very respectful of anyone who is crazy enough to give me money to make a movie.

Why did you want to tackle a subject as grand as Napoleon?

The personal life of Napoleon is hard to fathom unless you actually take a look at the man and the letters that he wrote with great passion. I would say [he had] an almost immature passion for this woman, Joséphine. What was it that made him need her? It went beyond the bedroom because the bedroom eventually will wear out. There was a need he had for her. She didn’t realize she needed him until he said, ‘We’re getting divorced.’ For him to get divorced from her was tragic because he needed a successor. So, you’ve got an evolving personal story. Once she’d left his side, he looked after her really well. He even took the baby that he’d wanted through her [and] gave her the baby to hold, which I thought was an incredibly beautiful thing to do.

Is it true you created more scenes for Joséphine during production?

Once she was out of the picture, I missed her. So, I started digging through her letters during editing. One of the most beautiful letters actually helped me with the ending, because I did not want to have Napoleon salute at Waterloo and get arrested and go away. I wanted to go on and on and on because that’s what happened. At the very end, when he’s on St. Helena, he’s imprisoned by an English governor who hates his guts. But that English governor had two daughters. Napoleon was enchanted by them and was seen to often sit and chat with them. One day, one daughter was able to wear Napoleon’s hat and wave his sword around in the orchard. That sat with me — my God, what an image! Over that I put the letter of Joséphine, who wrote, ‘You’ve had a go at Emperor and failed. Join me and let me now have a go to see how well we do.’ And then he died.

What makes Dariusz such a valuable collaborator?

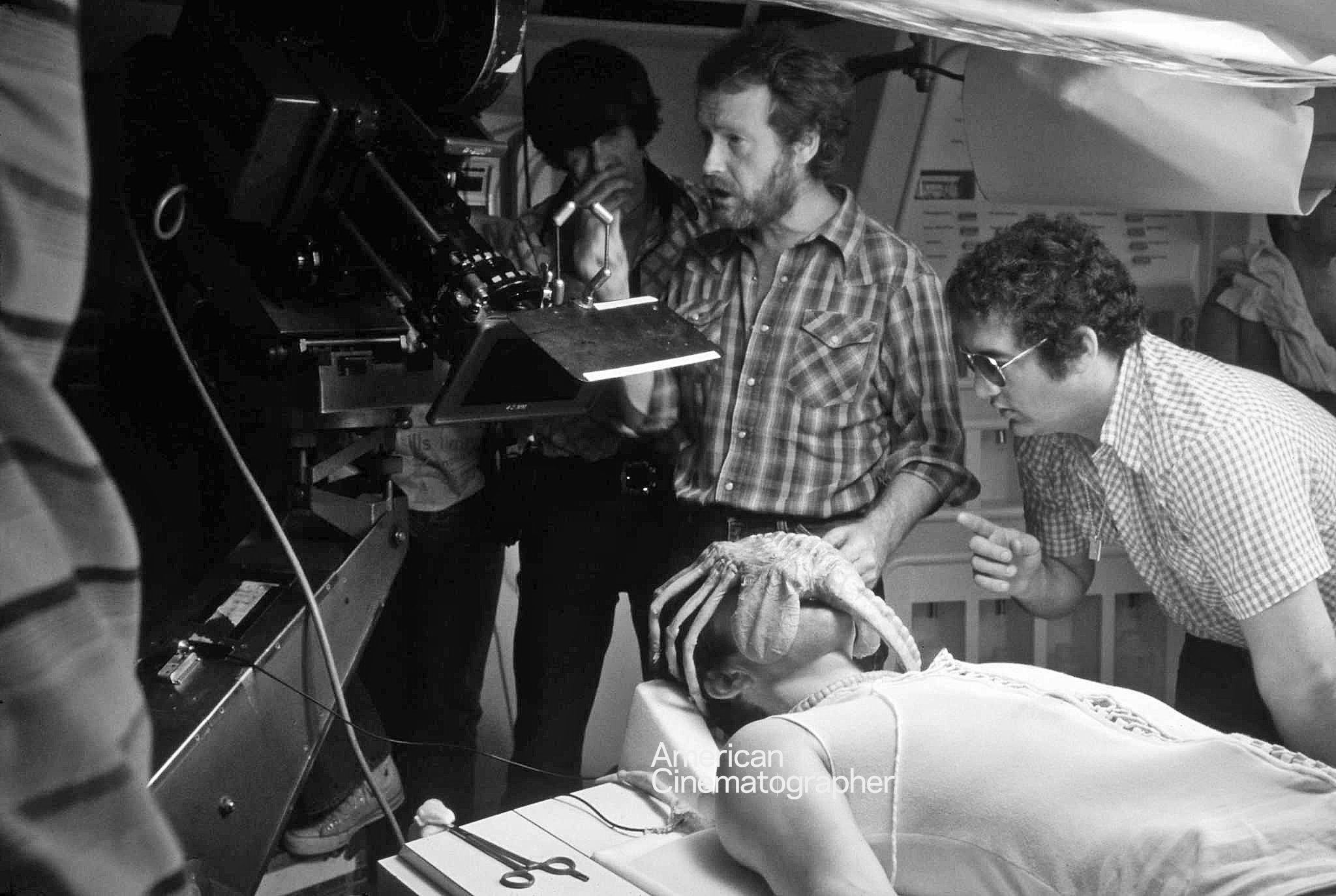

He copes with me! My pressure on Dariusz is huge. He has to be able to cope with an ambition of wide shots and close shots all shot together. That’s tough, [but] Dariusz is a master of that. I was a pretty good camera operator myself on 2,000 commercials, then The Duellists, then Alien. I’ve [always] worked very closely with a DP because frequently it’s the frame that is the most important thing. After that, it’s how you balance the light.

I did a thing [with multiple cameras] on American Gangster with another cameraman [Harris Savides, ASC], who was very good. I got on well with him, and he honestly did a terrific job on the film. But I started to introduce three cameras, four cameras, [and] he didn’t like that. I heard him talking to the gaffer, saying, ‘I can’t cope with all of these cameras, what do you think?’ And the gaffer said, ‘Actually, I kind of enjoy it.’

When you’ve got one camera, you do everything one way. Meanwhile, the actor off camera is quietly getting exhausted. When you come around to him, now he’s tired. I saw that the repetition was killing and slowing down the acting, and I like to keep the acting very alive. So, if you don’t rehearse too much, you know what you want, and you begin with at least two cameras, then you can easily do four. You do a medium shot and a close-up from each side with the same key light — what’s the difference? Then you move to six or eight. That’s where Dariusz is a master. He’ll just call me and say, ‘Okay, give me 40 minutes.’ I think he loves to move fast as well, and he is suited to me because he can cope and he thinks beautifully with the light.

How do you block a scene for multiple cameras?

I storyboard everything. My boards are very specific, from medium shot [to] close shot [to] wide shot. I can even imagine the location, so I draw the location and we tend to look for that location. The geometry is everything.

How do you make sure the cameras don’t capture the lights or other cameras and their operators?

I’ll do wide and, if we can get in, medium and close. Now we’ve evolved into an age where the cameraman is in shot. I’ve usually dressed him in the costume of the scene. All I’ve got to do is give him a glass of wine and take out the camera!

Blade Runner was famously overlooked upon its original release. Why do you think that was?

Sometimes I think the visuals [were] so strong that people couldn’t cope with the visuals and [still grasp] the story, which is very straightforward. So, you’ve got to be careful with your visuals. But then I think, ‘Well, wait a minute. I’m not doing radio plays, I’m making cinema!’

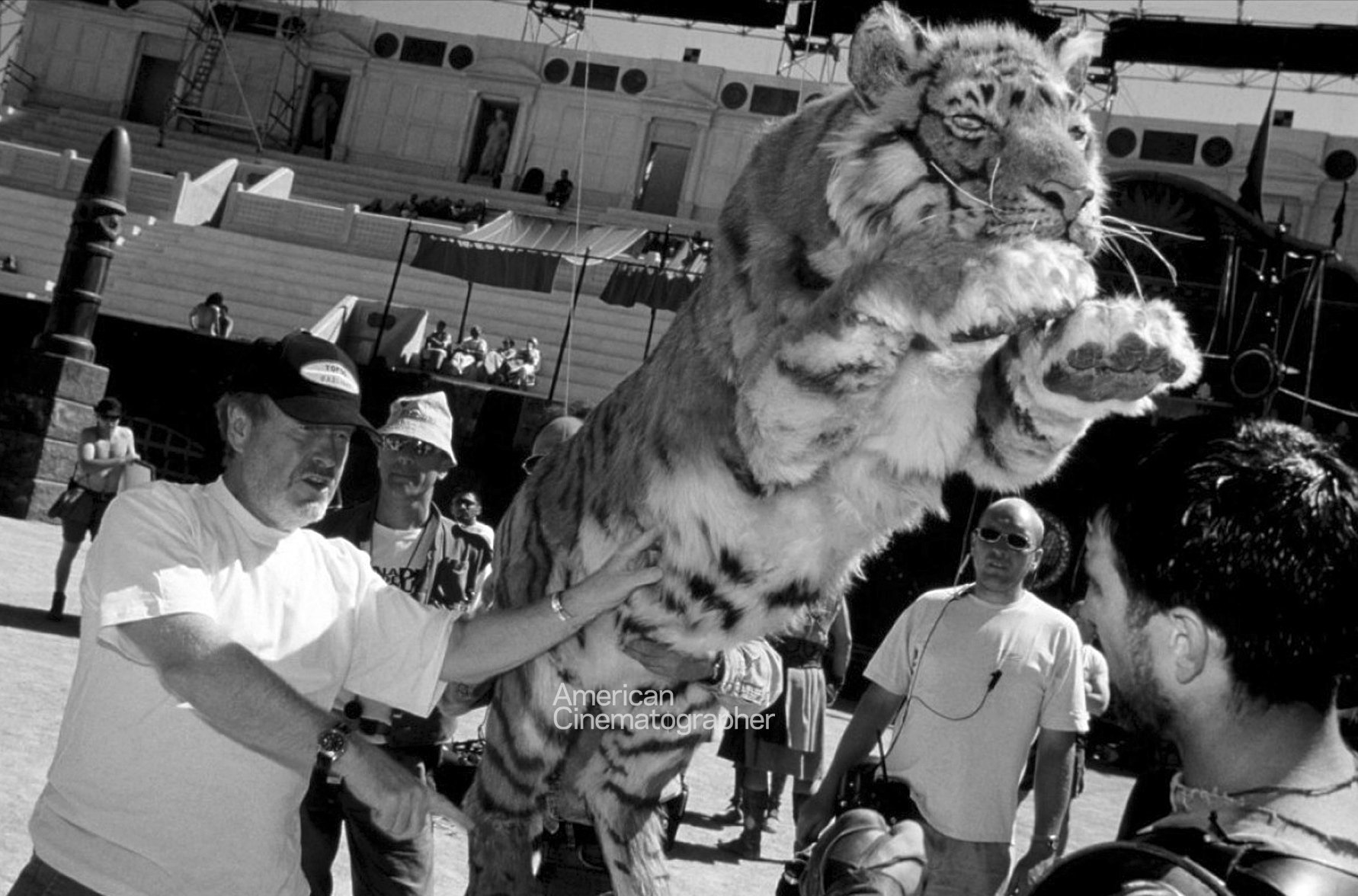

You'll find our complete story on the cinematography of Napoleon here. Our complete story on the visual effects can be found here.

Scott was honored with the ASC’s Board of Governors Award in 2016.

Napoleon Images courtesy of Apple Original Films