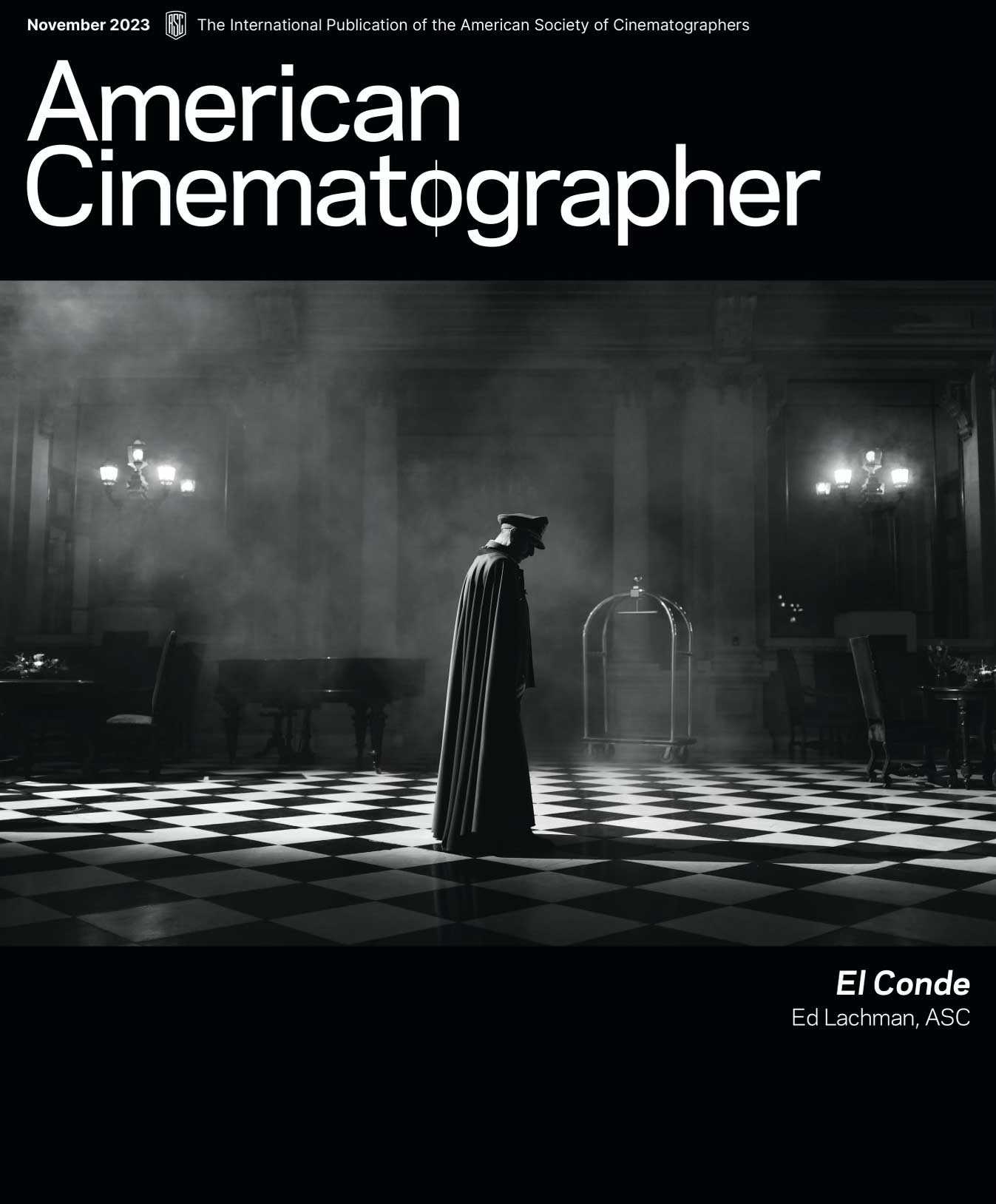

El Conde: Political Satire With Fangs

Ed Lachman, ASC and director Pablo Larraín imagine Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet as a vampire.

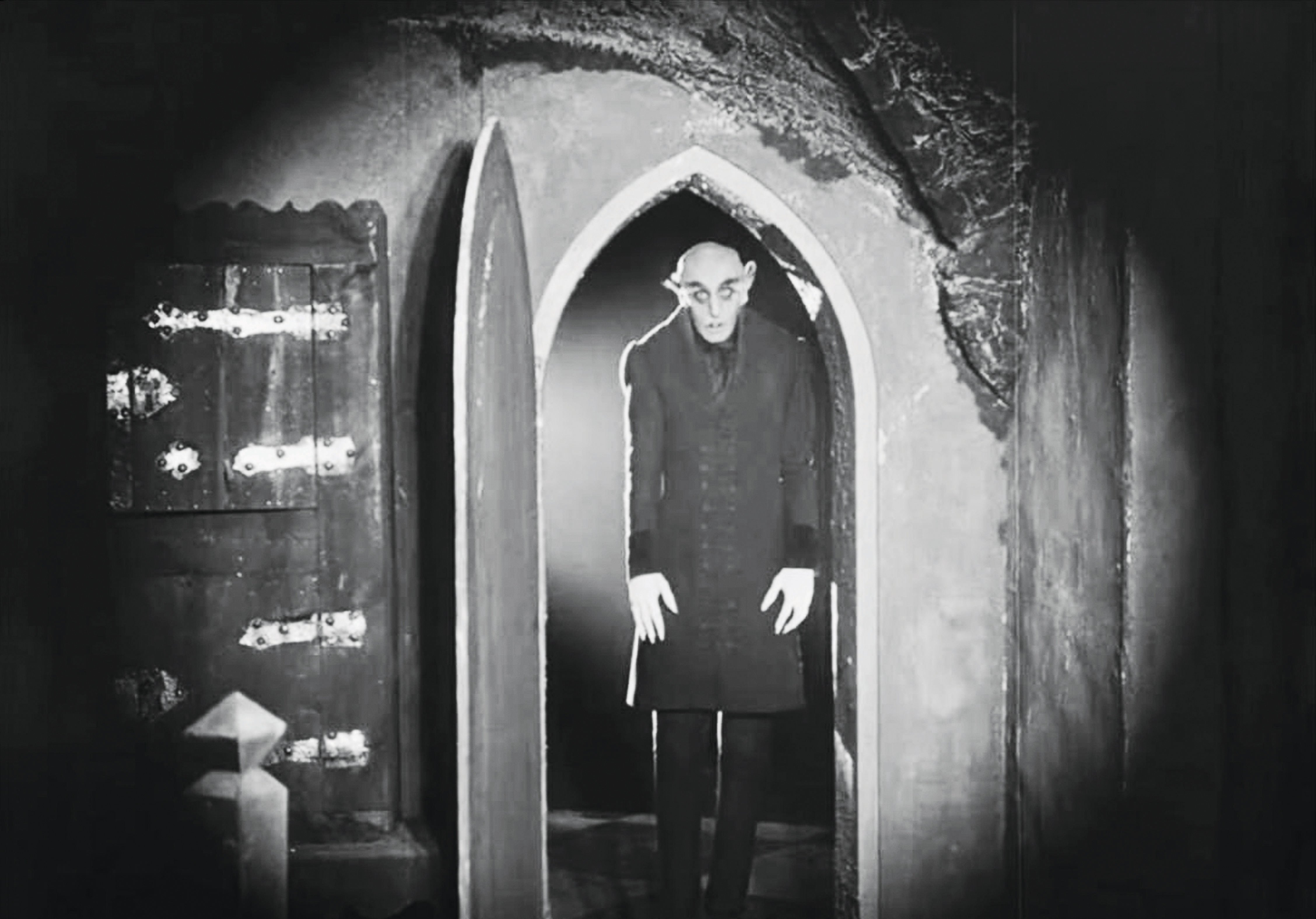

Vampire mythology has been with us for more than 1,000 years, and vampire cinema has thrived for a century since the 1922 release of F.W. Murnau’s Nosferatu, but the Netflix feature El Conde (The Count) offers a fascinating twist by presenting a controversial historical figure — Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet — as a vampire whose reign of terror has continued unchecked for 250 years.

While Pinochet’s actual term as Chile’s president, which spanned from a military coup in 1973 to his ouster in 1990, led to the torture, disappearance or murder of tens of thousands, El Conde finds him first lusting for blood in the late 18th century — as a young man in Paris. During the wee hours of the night, at the Place de la Concorde, he lasciviously licks the business edge of the guillotine blade used earlier that day to behead French queen Marie Antoinette in front of an angry mob.

This ghoulish scene, conceived by screenwriter Guillermo Calderón and co-writer and director Pablo Larraín, is presented in elegant black-and-white imagery executed (pardon the pun) by acclaimed cinematographer Ed Lachman, ASC, who says the vampire metaphor reinforces the idea that the lingering effects of Pinochet’s crimes against the people of Chile “will continue to haunt them forever,” since the dictator was never brought to justice. As presented in the supernatural realm of El Conde, Pinochet “becomes eternal as this dark figure. The film exposes Pinochet’s acts of depravity and evil within the fictional framework of vampirism, in the vernacular of the cinematic horror genre.”

Vampires are infamously seductive figures, another aspect of their mythology that the filmmakers found relevant in their depiction of Pinochet, who held an entire country hostage. The film’s exquisite images of glamour, decadence and decay effectively convey the pull Pinochet exerts upon those in his close control, including his scheming wife, Lucía (Gloria Münchmeyer), whom he stubbornly refuses to turn into a vampire; a devoted but devious manservant, Fyodor (Alfredo Castro), who’s having an affair with Lucía; his opportunistic children, who hope to inherit their patriarch’s vast fortune after Pinochet announces his intention to end his own life by becoming a vegetarian and refusing to consume blood; and Sister Carmencita (Paula Luchsinger), a nun appointed by the Catholic Church to pose as an accountant so she can infiltrate the former dictator’s inner circle to try to exorcise the demon within him and find where his fortunes are hidden. They all convene at a remote, hidden ranch on the barren, frozen tundra of southern Chile, in Patagonia, where the ailing Pinochet has become disenchanted with being a vampire.

In visualizing the arc of Pinochet’s journey through the abstraction and distancing nature of black-and-white cinematography, Lachman pursued several technical solutions that were not easy to achieve — including a monochrome digital camera that was in early stages of development, and a set of vintage optics that would cover Arri’s LF sensor. These tools and the “EL Zone System,” which Lachman had been developing with SmallHD, came together to enable a creative aesthetic strategy that lend the film the moody, magical feel of a Grand-Guignol folktale by way of the Brothers Grimm.

A Bespoke Black-and-White Camera

Lachman feels that using a color camera and converting to a monochromatic image limits the tonal mid-range and subtle contrast between the highlights and shadows, while a true monochromatic sensor produces images with more subtlety, detail and nuances in the shades of contrast.

For some years, Arri Rental had offered an exclusive black-and-white version of the Alexa XT, stripped of its Bayer mask and infrared filter, which enabled the system to capture monochrome images with greater resolution, contrast and sensitivity than the standard Alexa. More recently, the company had also developed an Alexa 65 variant which, unlike the XT, met the native-4K mandate required on Netflix productions. Lachman says he liked this latter camera option but knew that it would be too large and heavy, since most of El Conde would be shot with a 15' Technocrane, both to provide the kind of camera movement the filmmakers had in mind and to facilitate the setups.

Lachman reached out to his friend Marko Massinger, an ASC associate, film producer and imaging scientist from Germany, to ask if he thought Arri Rental could possibly install a monochromatic chip in the lighter, smaller Alexa Mini LF. “I had my doubts that they could pull it off, because Arri was coming out with their new Alexa 35 4K camera, so I figured all their effort would be going into that model,” Lachman recalls. “But Marko spoke with Manfred Jahn, the head of Arri Rental in Munich, and he was into the idea.”

The cinematographer also reached out to ASC associate Stephan Schenk, general manager of global sales and solutions at Arri, to see if the notion was possible. Jahn and Schenk both believed in the concept but weren’t sure if it could happen in the production’s timeframe. At that point, Lachman had already started prep, with two months to go before shooting commenced, and he didn’t think timely delivery would be feasible. To his amazement, 10 days before principal photography began, Arri informed him that they had a prototype camera ready, but that he would have to do the field tests himself to determine the sensor’s dynamic range.

Lachman was thrilled by the news, which meant he could use his old Harrison & Harrison black-and-white filters. “I also gained 3/4 of a stop,” he says. “ISO 800 was actually 1,280, and 1,280 became 2,000.”

Customizing a Set of Vintage Lenses

Another key element of the film’s visual design was Lachman’s use of original Baltar lenses from the late 1930s. While these lenses were originally designed for the Academy 35 format, longer focal lengths generally have a naturally larger image circle that can cover larger sensors. As it turned out, the lenses longer than 40mm in the original Baltar series had sufficient image circles to cover the slightly-larger-than-full-frame sensor of the Arri Mini LF monochrome. In order to fill the gaps on the wider end of the Baltar range with lenses that would cover the sensor, Lachman worked with ASC associate Alex Nelson of Zero Optik to source period glass with similar design and single-layer coatings. This work led to the creation of 21mm, 24mm, 28mm and 35mm lenses, as well as a 135mm to bridge the gap between the Baltar set’s 100mm and 152mm. Lachman named the added lenses in this set of “Ultra Baltars” — which, combined with the 40mm, 50mm, 75mm, 100mm and 152mm Baltars, gave the cinematographer a full range to choose from.

Original Baltar glass was memorably used on the classic films The Magnificent Ambersons (1942) and Touch of Evil (1958), among other famous titles. Lachman is quick to note that the lenses he worked with were not the Super Baltars created in the 1960s for reflex cameras. The Super Baltars had a totally different design and coatings than the original Baltars, which were used for rack-over (non-reflex) cameras, primarily on black-and-white films. “Alex turned me on to the original Baltar glass,” Lachman notes, “which have a different look than the Super Baltars. For me, period glass is like a bottle of wine, with a flavor in the elements that can change over time. How would you create that in modern glass?

“The charm of the original Baltar glass is that those lenses had fewer glass elements and coatings that were very simple compared to today’s lenses, which are more corrected.”

Applying the EL Zone System

With two key elements of his visual strategy in place — the monochromatic camera and the Baltar lenses — Lachman also deployed a third tool that proved instrumental to his creative approach on El Conde: the EL Zone System, which was being used for the first time on a theatrical feature. While some might presume that the “EL” stands for “Ed Lachman,” those letters actually mean “Exposure Latitude.” More information on this method can be found at elzonesystem.com, where Lachman explains, “I came up with the idea for purely personal reasons — originally because I was searching for a way to figure out how to use my methods from the analog film world in the digital world. In the film world, I used my meter, stops, Polaroids and the lab to create my own Zone System to interpret exposure and place the latitude of the negative so it would have detail in the highlights and shadow areas. Then, when the digital format became the new standard, I felt unsure about what I was doing and about relying on a DIT to create the looks I was after. I thought back to when I was in art and film school, and how I adopted some of the ideas from Ansel Adams’ Zone System, using 18% grey to create images from what I saw around me in the world, or images inspired by paintings, photographs and films.”

Adams’ Zone System, which the renowned still photographer formulated around 1939-’40 with fellow photographer Fred Archer at the Art Center School in Los Angeles, is a technique for determining film exposure and development — a codification of the principles of sensitometry that assigns numbers from 0 through 10 to different brightness values, each representing a photographic stop with 0 representing black, 5 middle gray, and 10 pure white. These values, or zones, provide photographers with a method of precisely defining the relationship between the way they visualize the photographic subject and the final result. While this system originated with black-and-white film, it can also be applied to digital photography. Lachman adapted the system after becoming frustrated with the imprecision of waveform monitors (“which don’t precisely map where over- or underexposure is within the frame, or even where 18% gray is”) and false color (“for which there is no standard between camera manufacturers”).

“SmallHD incorporated the system into their monitor as a profile for me to use as a prototype on El Conde,” Lachman notes. “I could finally demonstrate why IRE, which represents linear voltage values between stops, is actually false exposure in interpreting our stops — and why the EL Zone System works so well. The stops on our lenses, meters and the way we communicate to each other are logarithmic, meaning you have to double the exposure to formulate the next stop. When I researched IRE and what it stood for, I was astonished to find that it was designated for the International Radio Engineers — from 1895! — to track lightning from radio signals. So, I then understood why tracking exposure with a sound-based technology wasn’t such a good idea.”

A key advantage of the EL Zone System, according to Lachman, is that “its signal can be trusted for evaluating your exposure, no matter what ISO you’re using, and even if you’re using a range of different monitors or their calibration is off.” A cinematographer can “know what you’re really getting out of your camera when you’re setting exposure on set or on location, and establish and maintain consistency with your DIT and crewmembers while lighting.” Finally, by providing exposure-mapped frames for reference, the system “creates the exact exposure record and look from any previous scenes, in case you need to reshoot them later, even if you don’t use a meter. Your camera is your meter.”

The ultimate strength of the EL Zone System, Lachman attests, is the standardization of exposure and its usefulness as a language for communicating on set or during post. He adds, “On El Conde, as a cinematographer working in black-and-white, I felt like Ansel Adams, placing my exposure for the range of detail in the highlights and shadow areas and defining the image’s latitude.”

Lighting Strategies

One of the strongest visual elements in El Conde is Lachman’s lighting, which imbues the movie with a range of moods and tones. His approach to the remote ranch where Pinochet’s family has gathered produces moments that are, by turns, elegant, sensual, horrifying and darkly humorous — despite a relatively minimal lighting package mandated by the expense of transporting equipment. Although the cinematographer drew inspiration for the film from a number of artistic sources, “I tried to create our own language, influenced by the locations we found and the sets we created.”

El Conde was shot entirely in Chile, across six different locations: Valparaiso, Santiago, La Boca, Panquehue, Patagonia and the Chilean Antarctic. Working in the latter region in the wintertime, at the abandoned ranch, forced the filmmakers to confront the cold wind temperatures, as well as the changing light and clouds — which Lachman was able to turn to his advantage by creating dramatic landscapes.

The film’s key setting was actually a sheep farm in Patagonia, “but we shot the interior scenes of the farmhouse on a set in Santiago,” Lachman says. “I had to imagine what the light could be like two months later in the wide, open landscapes of Patagonia. I knew it would be winter, but that only meant it could be cloudy, or sunny, and that the weather could change very quickly. I had to come up with a solution on the set, knowing the weather could change at any time because of the season. Shooting interiors first, not knowing if the exteriors will match later, is a problem for any cinematographer. I talked to Pablo constantly about what time of day it would be for interior scenes, and my solution for the main areas of the house was to create a kind of semi-diffused light, coming mainly through the windows; I papered the windows and used the curtains as diffusion. I didn’t want the curtains to blow out when they were lit, so I had the production team make them a darker, warmer color. I also had the ability to modify the windows somewhat in post. I did that work in [FilmLight] Baselight at Harbor Picture Company with colorist Joe Gawler, who helped me retain all the details I wanted in the curtains. To my thinking, even if you have sunlight outside, you don’t always see that light come streaming through the windows because of the exterior porch.”

For the central room in the main house, Lachman established an overall ambience by hanging a 10K balloon with cost-effective PAR cans above an overhead 20'x20' muslin. A chandelier is a prominent focal point of the room, so Lachman had the crew install larger 40-watt bulbs in the chandelier itself, using that as source lighting along with box lights above the chandelier fixture. He also had the lights on dimmers to provide control. “I was aiming for a naturalistic expressionism with texture in the shadows. So, in that main room, I might have the lights coming from camera-right through the window, and I would dim the lights on the left; then, when the camera moved right, I would bring down the lights on the right and up on the left. I basically used the dimmers to control the source-light level, while still lighting from the windows.”

For additional areas of the Pinochet compound, light fixtures were built into the sets, as in a freight elevator where Astera tubes are visible, and in the long hallway that leads to Pinochet’s blood-storage room. The hallway was tricky, because we were always fighting the shadow of the Steadicam operator if he got too close to the actors as they were walking. The set, which had to match a real location, was lined with overhead PAR cans aimed down through 1000H paper to supplement the bare hanging bulbs positioned along the corrugated walls. Utilitarian fluorescents were also deployed in the refrigerated storage room, and in the treasure room where Pinochet stores prized possessions collected over the years. Lachman offers, “The idea for those areas, and in the rest of the house, was that the lighting and furniture was always makeshift, without the characters thinking about any style or decor.”

Blood Work

Lachman worked closely with production designer Rodrigo Bazaes; costume designer Muriel Parra; and the head of the show’s makeup and hairstyle department, Margarita Marchi, to add the appropriate textures and gradations to the onscreen images. “Knowing that we would be shooting in black-and-white guided our designs for the wall textures, the wardrobe and everything else,” Lachman observes. “We darkened and aged the walls to provide contrast against the characters and applied textures to the sets to enhance the feeling of the debilitating environment.”

Of course, one key consideration in any vampire movie is blood, but the movie’s black-and-white format led the team to settle on a blue-colored substance. “We did tests with the blood, and the red came through beautifully rich and deep,” Lachman says, “but when we tried blue, it gave the blood more of a luminosity and transparency I never would have gotten with red.”

Up in the Air

Some of the film’s most magical, transcendent scenes occur when Pinochet and the young nun — whom the dictator finds inviting enough to bite — take to the air thanks to their vampiric ability to fly. Scenes involving Pinochet flying at night were shot on a stage against bluescreen with a color LF camera, provided by Congo Films in Colombia, and then converted to black-and-white. However, the flying sequence with Sister Carmencita was shot on location in Patagonia with the actor, Paula Luchsinger, suspended from a 160' crane and working with Colombian acrobats and a stunt double. “But, honestly,” Lachman says, “a major percentage of those shots were done with Paula, who was once a ballet dancer. She really wanted to do the flying footage herself.”

The resulting images of the nun soaring through the air in ecstatic rapture have an exhilarating quality enhanced by the authenticity afforded by their staging. “For some of those shots, the operator was seated on the crane, handholding the camera while she was flying attached to the wires,” Lachman says. “In others, a grip held a [DJI] Ronin rig on a suspended seat while the operator worked from wheels on the ground.”

“The pain is eternal”

In the cinematographer’s discussions about El Conde with Larraín, the director stressed the idea of “evil being able to feed itself like a vampire in order to survive,” Lachman says. “Unfortunately, history needs to repeat itself to remind all of us how dangerous we can be — and how any person may have the same capacity to be immoral, corrupt or diabolical.

“Pinochet was never tried for his crimes,” Lachman points out. “He died wealthy and free of his crimes against the people of Chile. The people who were directly hurt and their families never found justice or relief. The injustice and pain is eternal — it’s forever.”

The cinematographer subsequently spoke about the film in this ASC Clubhouse Conversation episode, with interviewer Greig Fraser, ASC, ACS:

Tech Specs:

2:1

Cameras: Arri Alexa Mini LF Monochrome, Alexa Mini LF

Lenses: Baltar, Ultra Baltar

Aesthetic Influences

Ed Lachman, ASC’s approach to El Conde was partly inspired by classic movies, including several from the German Expressionist school. Some of the key titles were F.W. Murnau’s Nosferatu (1922, shot by Fritz Arno Wagner and Gunther Krampf) and another Murnau gem, Sunrise (1927, shot by ASC members Charles Rosher and Karl Struss); Carl Theodor Dreyer’s Vampyr (1932, shot by Rudolph Maté, ASC and Louis Née); and Josef von Sternberg, ASC’s Shanghai Express (1932, shot by Society members Lee Garmes and James Wong Howe). Lachman says he drew from these films’ “chiaroscuro and the physicality of the light, as well as their use of textures in the sets. The visual strategies really support the themes of their stories.”

Still-photography references for Lachman included the work of Fan Ho (whose images he admires for their “subjective, cinematic approach to street photography, especially in terms of the light and the staging of subjects”), Alexey Titarenko (whose images present “introspective movement in daily life as an abstraction”) and Maura Sullivan (who created “mysterious and poetic images using in-camera reflections and refractions”).

Other artists who helped inspire Lachman’s aesthetic strategies included the painter Antoni Taulé, conceptual artist John Stezaker, collage artist Katrien De Blauwer and assemblage-box artist Joseph Cornell.

— Stephen Pizzello

Director’s View | Dictatorship as Vampirism

Ed Lachman, ASC spoke with director Pablo Larraín about exploring the reign of Augusto Pinochet — and the undying nature of dictatorship — with¬in the framework of a vampire story.

Ed Lachman, ASC: What do you feel El Conde is about?

Pablo Larraín: It’s about impunity, how justice is really a collective desire, but not a reality — how horrible crimes and a lot of horrible things that happened in history did not get their due justice. I don’t believe, at the end of the road, that people get their deserved justice.

How did you come upon the idea of depicting Pinochet as a vampire?

Societies and countries like ours that were colonized — they were also colonized with all sorts of ideas. Racism is not our invention; [it comes from countries that] call us the “Third World.” And that leads me to the other invention that comes from here, the Northern Hemisphere — the romantic vampire story. So, I believe we took two elements: One is the vampire story and the other is racism — and that’s the cocktail of this film, I suppose.

Healing is very needed after that time in Chile with Pinochet, but the healing comes after justice. We were never able to take him to trial. He died not only a millionaire, but he died free. He will always be around us. It’s not just the generations to come, it’s forever. So, the only way we can deal with him is through the idea of the vampire — it’s a very simple metaphor.

Amid all the evil the film explores, there is also a lot of beauty. Can you discuss the idea of combining these two contrasting elements in the film’s imagery?

Possibly the most dangerous [idea] — and because of that, possibly the most interesting one — is that evil can create beauty whether you like it or not. Beauty can come from evil, not only from goodness. There’s something in darkness that can create a very strange, attractive sensibility. And it’s in music, plastic arts, painting, theater, sculpture, opera and cinema — and human expression of art can flirt with darkness. Even if you are a politically correct person who says, “I’d never flirt with those ideas” — yes, you have, whether you like it or not. There’s always something there that’s interesting. After certain scenes, even the production designer would come to me and say, “You see? Evil can create beauty.” And we, as an audience, are able to see that, and with film you are able to shoot it.

I’m not saying that working around these figures redeems them. I don’t want to redeem these bastards, I want to expose them — and when you do that, maybe you find beauty in that, and maybe that’s the only way you can feel, just by the exercise of trying to portray them. We find redemption in ourselves when we see them and analyze them. When we look at them, we have an understanding of who we are, and also why we allowed it to happen. We’re a part of that, too.

— Edited by Andrew Fish