Beyond the Law: Prisoners

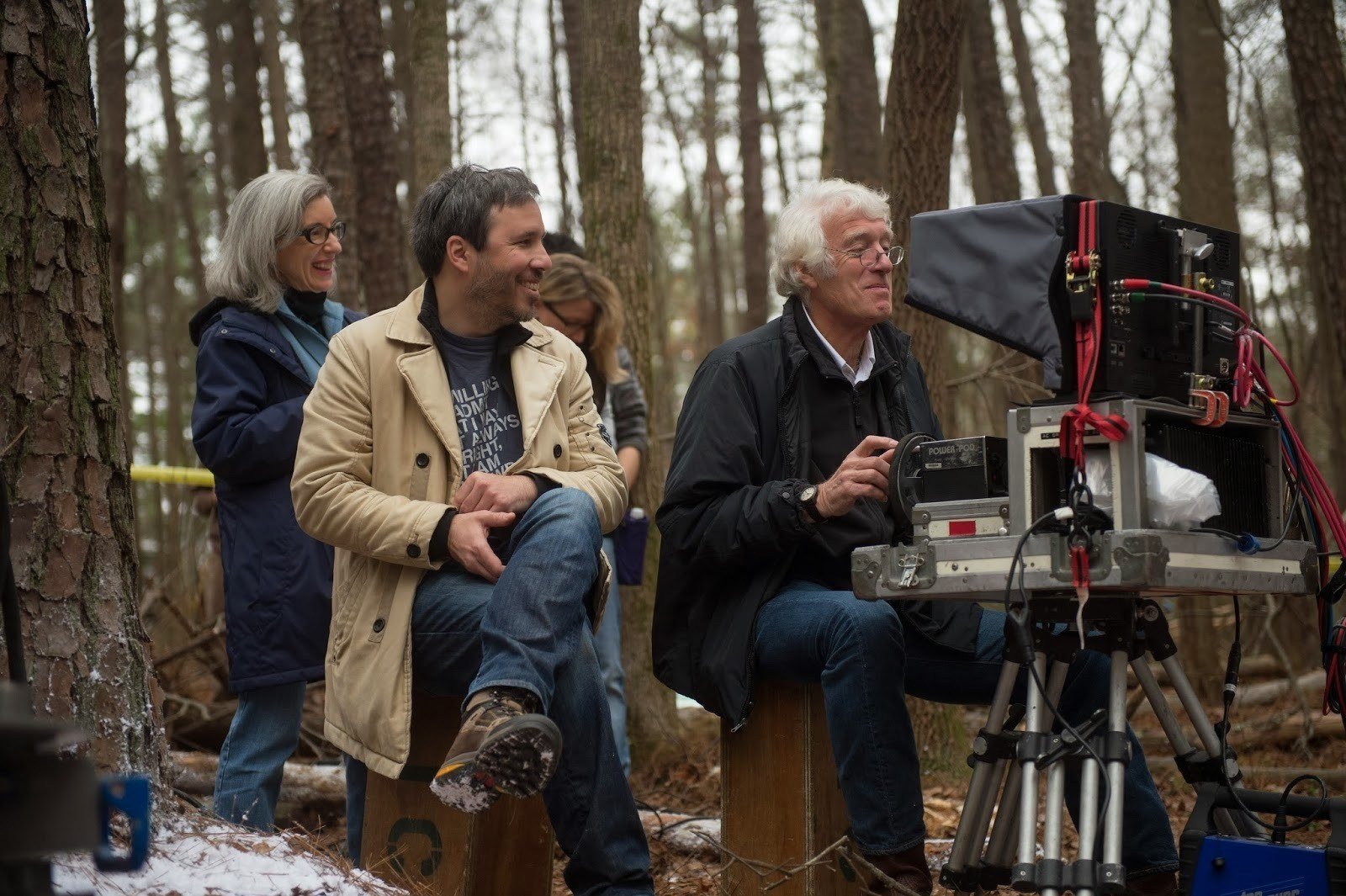

Roger Deakins, ASC, BSC details his lighting approach to this disturbing police procedural with compelling plot twists.

Unit photography by Wilson Webb

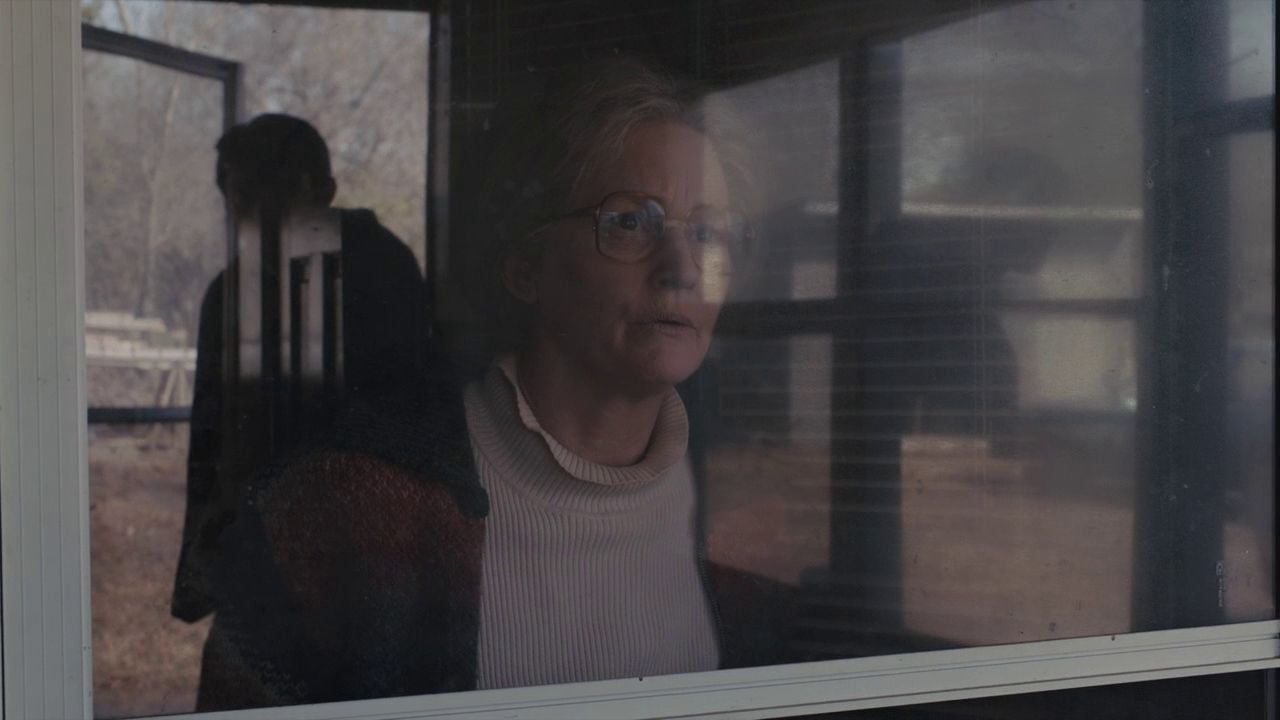

Set in an unassuming suburbia, Denis Villeneuve’s drama Prisoners begins as two neighboring families convene to celebrate Thanksgiving. After two of their young daughters vanish without a trace, a tenuous string of clues and frantic desperation leads one father, Keller Dover (Hugh Jackman), to step well outside the law as he tracks, captures and imprisons the man he believes responsible, Alex Jones (Paul Dano). Meanwhile, the police investigation, led by Det. Loki (Jake Gyllenhaal), is uncovering a conspiracy involving child abductions that have taken place over decades.

“I heard Denis was doing this movie and got the script, which was dense and had a lot of characters, and, to be honest, Gothic elements that I thought went too far.”

— Roger Deakins, ASC, BSC

Prisoners cinematographer Roger Deakins, ASC, BSC says a number of elements in the story struck him as timely, “the issue of torture among them,” and that he was also attracted to the project by its emphasis on character and performance. “The dramatic success of Prisoners rests on the acting,” he says.

He had also been impressed by Villeneuve’s last feature, Incendies [2010], and was keen to collaborate with the director. “I heard Denis was doing this movie and got the script, which was dense and had a lot of characters, and, to be honest, Gothic elements that I thought went too far. I wasn’t interested in that genre, but it turned out that Denis wasn’t, either. We did end up shooting the script, but it was always his intention that the final cut of the film wouldn’t feature those elements.”

Prisoners unfolds mainly through the perspectives of Dover and Loki as their respective investigations progress. “Denis and I talked at length about how to ground the movie in those two perspectives, but we didn’t want to do it in an effects-y way,” Deakins says. “For a while, we considered shooting the whole film handheld to give it a slightly raw feel, but that didn’t feel right. It’s a dramatic story, not documentary realism. Also, there was a danger of some of the Gothic elements being kind of over-the-top, and we wanted to play those down, not amplify them. So, in the end, we chose a very restrained, matter-of-fact style of camerawork. We didn’t need the camera to punctuate the suspense, because the suspense is there in the story and the characters.

“I guess more and more, I want to do less and less with the camera. Sometimes, well, we do too much.”

The subtle visual style is in some ways reminiscent of Deakins’ work on another, very different police procedural, Fargo (AC March ’96). “Denis and I did actually talk about Fargo, mostly about that sort of restraint,” the cinematographer reports. “There are some sequences in Prisoners that we did handheld, but we became aware as we got into it that handheld didn’t work for this story. It’s kind of interesting that we settled on this almost clinical approach to the camera. A number of people call it ‘classical,’ or even ‘old-fashioned.’ Some people think a handheld camera, lots of action, and zooming in and out and finding focus as you go looks ‘modern.’ To me, that’s ridiculous, and I hate that kind of look.”

Instead, the sober camerawork in Prisoners draws the viewer into the drama’s labyrinth of emotions. This is perhaps best illustrated by a sequence in which Dover ruthlessly interrogates Jones in the confines of a small, dingy bathroom, where he has chained Jones to a radiator. As his friend and fellow parent (played by Terrence Howard) looks on, horrified yet hopeful for information about his own missing daughter, Dover beats Jones to a bloody pulp. “It’s interesting because you don’t actually see a lot of the violence,” says Deakins. “So much of it is implied, in part by how long he keeps Jones captive. Somehow, you can understand why Dover is doing what he’s doing, but he does cross a line, and it puts the viewer on the spot: What would you do? Is this justifiable?

“That’s why I approached the story as a morality tale, a kind of microcosm of the whole idea of torture. It’s tough material but very worthwhile.”

Prisoners was shot on location in the suburbs of Atlanta, Ga., and Deakins says his lighting approach was determined as much by the available locations and the blocking of action as it was by the story itself. “Deciding on the lighting is always difficult,” he says. “So often you might have an idea going in, but you can’t get trapped by that because so much depends on the reality of the shooting day. Denis and I looked at a lot of visual references, and we definitely had a look and a feel in mind when we began, but the way it finally came out was a much more organic process, to use an overused expression.”

Deakins shot the picture digitally using an Arri Alexa Studio, an Alexa Plus and Arri Master Prime lenses, capturing in ArriRaw. “I needed the exposure the Master Primes offer because we had some very low-light situations,” he says. “I rated the Alexa at 1,600 for those, but for most night [exteriors] I usually rated at 1,250 ASA. Everything else, apart from a few day exteriors, was rated right at 800 ASA. I like to shoot right in the middle because the image will have more latitude and more dynamic range.”

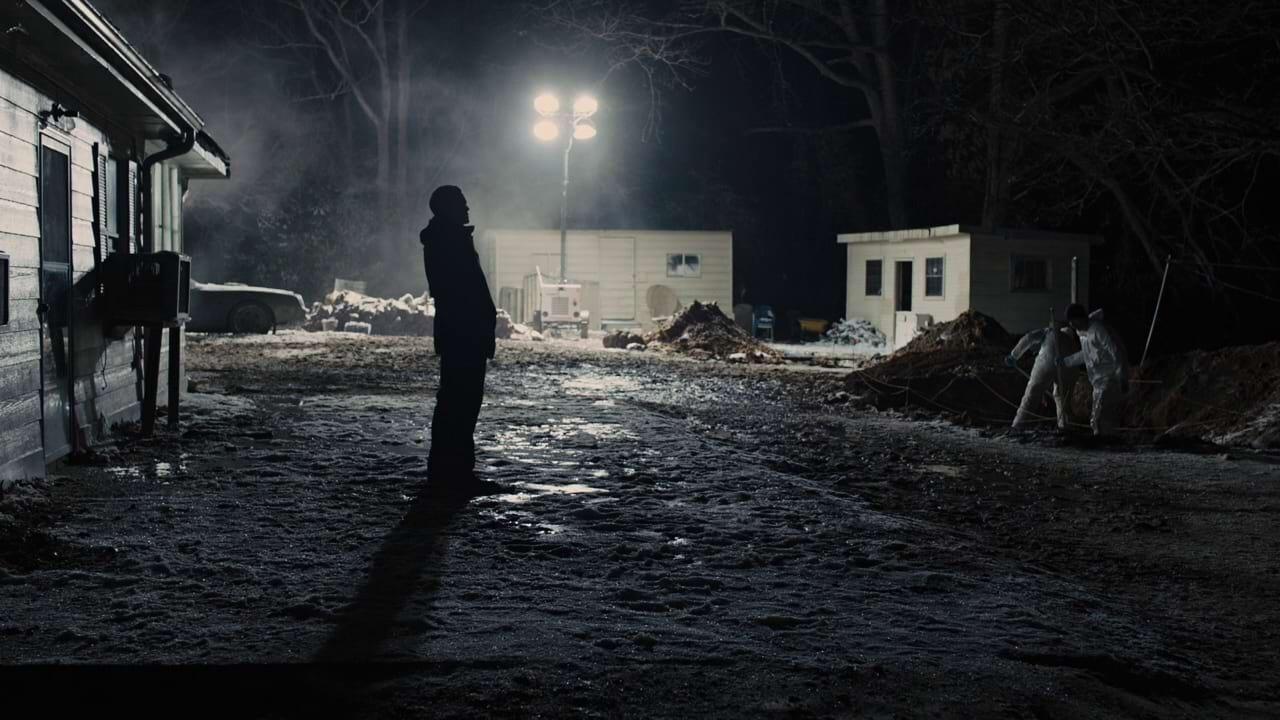

Basic source lighting was the rule throughout much of the production. As an example, Deakins points to a rainy night sequence in which Loki and other police officers converge on Jones’ dilapidated RV, surrounding the vehicle in an isolated parking lot. “Originally we looked for a highway rest stop for this scene, but as we discussed it, I realized that sort of location probably wouldn’t have any sources to work from, and I didn’t want to create a moonlight look because that would’ve looked artificial,” says the cinematographer. “So, I suggested we have the RV park by a gas station that had a big parking lot, which would allow us some light sources and add depth to the landscape. I liked the idea of this bright gas station in a sea of blackness in the rain, and the RV parked off in the darkness. Visually, that’s how the scene evolved, and it became one of my favorites in the film because it’s such a statement, such a harsh look.

“So, we had our setting and the lighting of the scene, and then adding to that is the staging of the action. Loki first appears in silhouette, coming out of the blackness, with other officers approaching with their flashlights, and then we see the RV and its headlights poking into the woods past the edge of the parking lot. So, our lighting approach helped dictate the location, which then helped dictate the staging of the scene, which led to the actual lighting — it was an evolution. Basically, we lit the film by choosing the right places to shoot it.”

Chief lighting technician Chris Napolitano, one of Deakins’ regular collaborators, elaborates: “We kept the lighting in this scene pretty simple, and we started by boosting the RV headlights with a couple of Tweenies mounted on the front. Then, each policeman had a flashlight practical fitted with 500-lumen LEDs; the conversions were done by Independent Studio Services, a prop house in Los Angeles that also converted a number of camping-style flashlights for us. Depending on the scene, Roger would usually warm the flashlights a bit with CTO.

“There was a large billboard near the parking lot, and we got permission to access it so [rigging gaffer] Kevin Lang and the rigging crew could put up some 400-watt Joker Pars, aiming them down to create pools of light. A little of that was set up to backlight the rain, but we didn’t need that too much.

“For shots [looking] the other direction, Roger used a dozen or so 2K Juniors to create a look off in the distance. We put them in a nice line and dimmed them to about 20 percent, creating a soft glow in the background, out of focus, for depth.”

Location also dictated lighting in a unique reveal sequence that introduces Loki on that Thanksgiving evening. He is eating dinner alone in a near-empty Chinese restaurant that has large glass windows, allowing the camera to easily pick Loki up even in relatively long shots from outside. “What’s funny is that while scouting for that scene, we looked at all these standard Chinese restaurants, but none of them had an interesting exterior,” Deakins recalls. “I suggested to Denis that if we wanted to feel Loki is alone, we’d have to see inside from the exterior. So, we kept looking, and we finally found this pancake house that was available. It wasn’t a Chinese restaurant, but Denis said, ‘If we add red chairs and chopsticks, it’s a Chinese restaurant.’ The scene has this minimal, ugly look, with the highway outside and the rain coming down, and he is the loneliest guy in the world.”

The solution to lighting the interior of the restaurant was China balls, “but that had nothing to do with it being a Chinese restaurant,” Napolitano says with a laugh. “The shape of the restaurant was kind of octagonal, with these huge windows, so Roger came up with a plan to light from the central ceiling of the room with white paper China balls. [Key grip] Mitch Lillian and his crew put together a cable line for us to hang them from so we could slide them around as needed.” Napolitano used 19" China balls fitted with sockets and 100-watt household bulbs, which were dimmed down to add warmth. No fill was used, as the fixtures cast such a soft, realistic toplight on Gyllenhaal.

One of Prisoners’ key suspense sequences takes place during a candlelight vigil, as dozens gather to raise public awareness about the girls’ disappearance. Loki scans the crowd for suspicious-looking attendees, and the scene quickly changes gears to become a chase through neighboring backyards. “That was a sequence Denis storyboarded, and we shot it more or less as we’d planned,” Deakins says.

Again, Deakins’ lighting strategy was to rely mostly on practicals. “I didn’t want to put any extraneous light on the scene by using overheads on towers or Condors. I wanted the candles to be our main source, so we got a lot of double-wick candles and then dummied a number of them with electric versions for the background; we concealed the bare bulbs with those same little plastic cups people generally use on candles to protect them from the wind.” Napolitano adds, “At one point, the scene had 60 to 70 extras, so we had about 30 of our dummy candles on dimmers. Those double-wick candles are never enough, and Roger came up with the idea of mixing about 20 peanut globes in with the candles that were placed on the ground, and that gave us a warm glow coming from below eye level.”

Deakins abandoned the idea of using flicker generators for these candle fixtures because “it got too complicated for what we were trying to do,” he says. “We ended up putting them straight on dimmers, which was quicker. I also had 2-foot and 3-foot aluminum strips made that each had six or seven sockets, and we’d hide those behind a pillar or an actor to give a bit of light on something else, to boost the effects of the candlelight.”

For this scene, Deakins rated the Alexa at 1,600 ASA “because it was very minimal lighting, and I wanted to push [the candlelight feel] as far as I could. I could have probably shot the whole scene just with triple-wick candles, but the flames would have been too large. I find the extra bit of speed I get with digital is a real advantage to the way I like to work. But I won’t go any further than [1,600 ASA], not on the Alexa. You could, but at 2,000 ASA you start getting a bit of noise.”

The wild foot chase that begins at the vigil and moves through the neighborhood “was lit entirely with many little gags that we’d rigged on the ground well in advance,” Deakins says. “One of the pluses of working in the same neighborhood for weeks was that I could come out at the end of a day’s shoot in one place and start doing a little bit of lighting elsewhere. The rigging crew put in all these gags using little mushroom bulbs on the houses and in the backyards, and then they added Redheads behind each streetlight to augment that light a bit. We also set up the streetlights themselves, as none existed at the location; basically, we started with nothing. By the time we came in to shoot, the backgrounds were done, and we could shoot from virtually any angle. It’s all lit by what you see in shot, with a little extra floor lighting on the day.”

“We were getting away from the standard night-exterior look of a huge backlight coming down on a wet street, you know?” says Napolitano. “This approach was more suited to this type of neighborhood. Our local crew guys were kind of blown away by this practical-heavy approach! And Roger’s attention to detail is incredible. The crew might set 30 gags in an area, but if one was missing, he’d turn to me and say, ‘Chris, that overhang there doesn’t have the light I need.’”

Many of these gags comprised a practical that would be visible on camera surrounded by a ring of smaller lights that would be just out of sight. “And then, inside some of the houses and garages we’d drop a batten strip of 150-watt RFL globes to create a soft push of light coming out of, say, a kitchen window into the back yard,” says Napolitano. “We also placed lights off in the distance, at different levels, to add something in the background for depth.”

In addition to the practicals built into the houses and streetlamps, the electricians sometimes added securitytype fixtures bought from a local hardware store and rewired for higher output. “We could use those anywhere,” Napolitano says, “and sometimes we’d use a few 1K Nooks raking across a yard, or, at most, a couple of 2K Juniors and Babies. But household incandescents were our go-to for much of the scene, and we used a lot of gold bounce cards to give a nice, soft push of light coming from the corner to enhance whatever fixture was working off the house.”

Napolitano adds that although the production made extensive use of dimmers to control lighting, the approach was decidedly low-tech. “I’ve done some huge movies that relied on massive dimmer-board systems, but on this movie we used old-school 1K and 2K Variacs pre-rigged into position and marked so we could reset them as necessary. We also installed a lot of dimmers in walls on our locations, wherever we needed a dimmer on a practical, and then wired another light with it. So, if there was a bedroom light on a switch, we would wire into it another light so that when the actor came in, he’d just hit that switch on the wall, and it would light the practical and our light with it.”

One of Deakins’ biggest lighting challenges was a night scene at the end of the picture that shows a character trapped in a cave-like bunker, and Loki searching just yards away from it. The policeman is on the verge of giving up his hunt, which would mean almost certain death for the trapped character. This exterior sequence was staged in the front yard of a ramshackle house, and largely lit by boosted household practicals and a series of police work lights illuminating the outer area. “I struggled with those last few shots of the film because I was working with the idea of how to light that house but also add some tension,” Deakins recalls. “Then we decided it would make sense for the police to have rigged work lights, and they could turn them off one by one as they prepare to leave.”

“I like photographing a human face. I find that more interesting than anything else, and that’s what I will continue to do.”

In essence, the trapped character’s chance of living dims as each of those lights is extinguished. Deakins notes, “I’ll always remember that wonderful shot Connie Hall [ASC] did in Fat City, when the aging boxer that Tully [Stacy Keach] has just beaten is walking down a passage, and they turn the lights out as he goes through. I always thought that was a wonderful shot, and I may have had that in my mind.”

To create a base illumination for the scene, the house’s porch lighting was intensified with fluorescents until it “became a kind of bowl of light that could reach out into the yard just far enough to light it to the edge of [the cave’s location],” says the cinematographer. “But justifying having enough light to get out there from the house was tricky.” The work-light practicals then completed the effect.

The production’s dailies were timed on location by EFilm colorist David Picket, who graded the native ArriRaw 2880x1620 files using Colorfront On-Set Dailies. Deakins viewed the results projected on a 17' screen (at 2048x1152) and via EFilm’s eVue system. Dailies were transcoded to Avid DNxHD for editorial.

Deakins did the final timing at EFilm in Hollywood with colorist Mitch Paulson, who graded 2880x1620 DPX files on an Autodesk Lustre. Final outputs were a 4K DCP, a 1920x1080 HD master, and a 4K filmout (on an Arrilaser) to Fujifilm Eterna-RDI 4511. Deluxe Laboratories in Hollywood made the answer print.

Deakins took on Prisoners shortly after wrapping the James Bond adventure Skyfall (AC Dec. ’12), and he says he found Villeneuve’s film “harder to shoot, in a way, because we didn’t have the luxury of all those tools and an endless amount of prep. But, in all, Prisoners is much like the films I’ve been doing for most of my career. I like character films. I like photographing a human face. I find that more interesting than anything else, and that’s what I will continue to do.”

1.85:1

Digital Capture

Arri Alexa Studio, Plus

Arri Master Prime