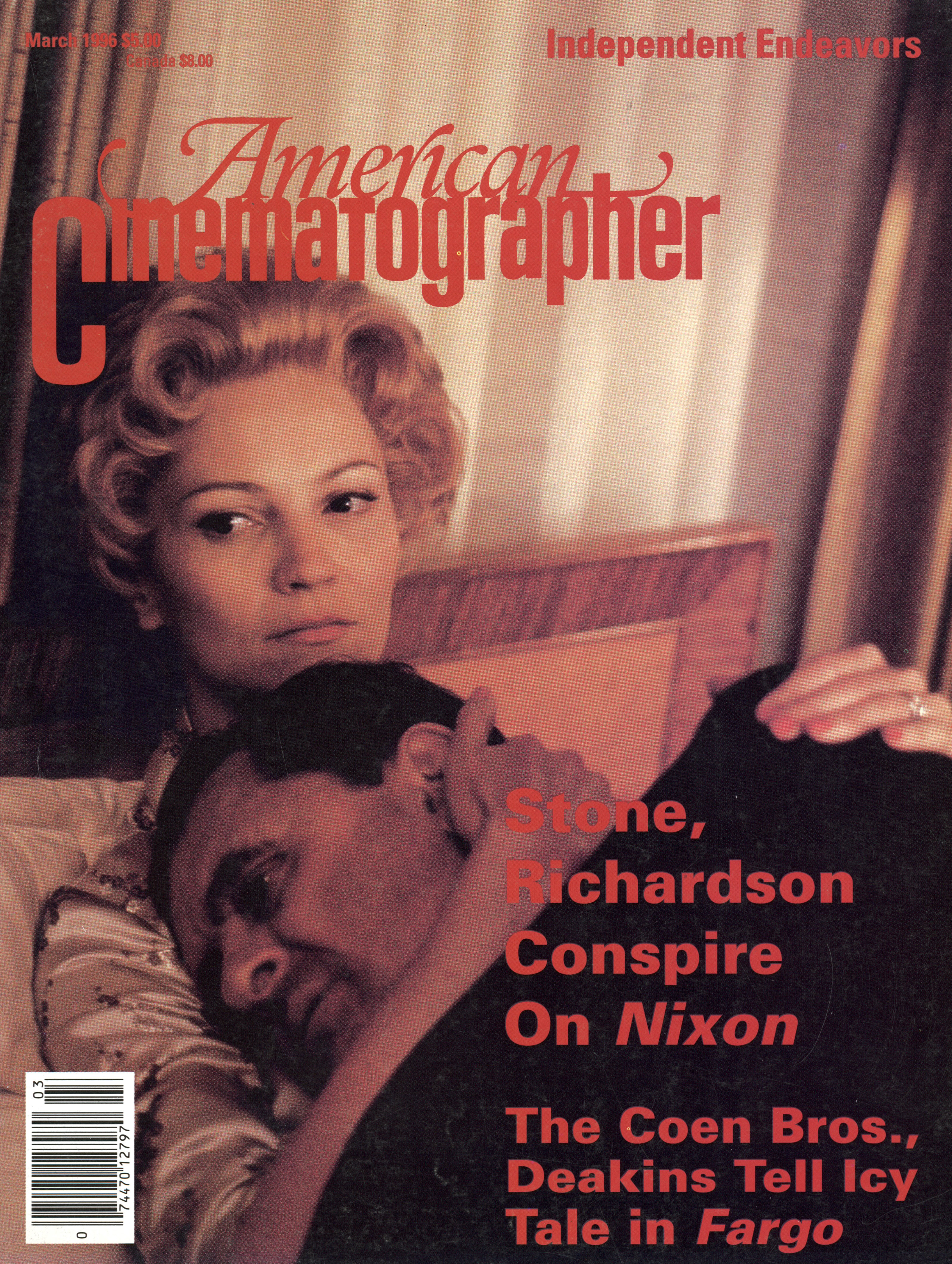

Fargo: Cold-Blooded Scheming

Roger Deakins, ASC, BSC teams with Joel and Ethan Coen for the third time, to tell a tale of a kidnapping gone awry in the chilly clime of Minnesota.

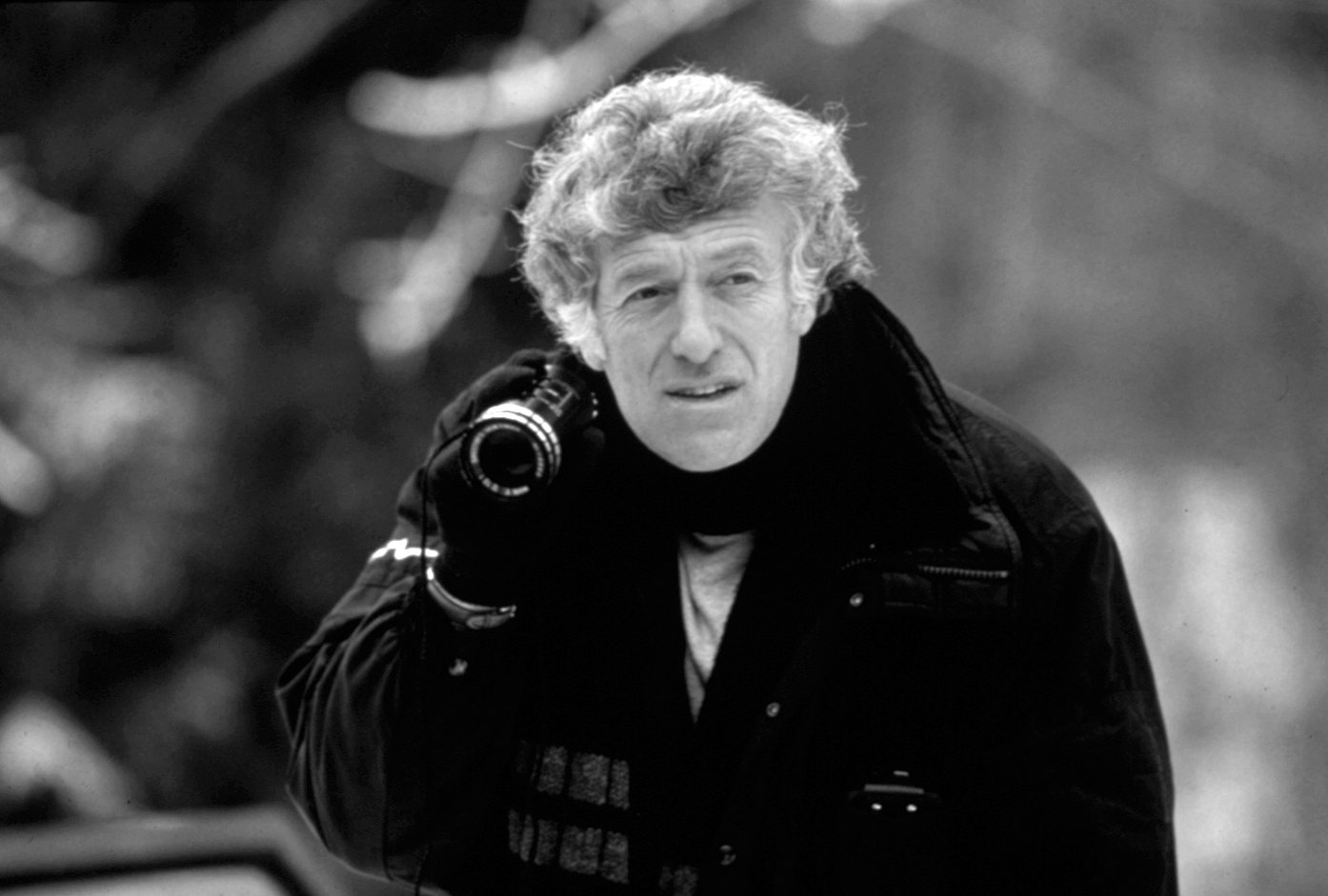

Roger Deakins, ASC, BSC's association with the filmmaking duo of Joel and Ethan Coen began on Barton Fink, and the echoes of that first collaboration still haunt the cinematographer.

"Roger still teases us about making him track down the plug-hole in the sink," says writer/producer Ethan Coen.

Joel, who co-writes and directs all of their films, laughs and adds, "It was the only moment on Barton Fink when I think we really surprised him. But that shot was a lot of fun and we had a great time working out how to do it."

Interrupting his brother, Ethan continues their simultaneous telephone-interview tag-team act, which the duo insist upon with unsuspecting journalists. "But now, whenever we set up or talk about a shot that's even remotely strange, Roger arches an eyebrow and says, 'Don't be having me track down any plug-holes now!"'

With Fargo, Deakins and the Coens continue in the outlandishly quirky and unique vein they previously tapped in both Barton Fink and The Hudsucker Proxy, while the cinematographer's other credits present a diverse mix that includes 1984, Sid and Nancy, Mountains of the Moon, The Secret Garden, Passion Fish, The Shawshank Redemption (which earned the him last year's ASC Award, as well as an Oscar nomination) and the recent Tim Robbins film Dead Man Walking, which has garnered widespread critical acclaim.

Set in Minneapolis, Minnesota, in the dead of winter, Fargo’s storyline revolves around debt-stricken car salesman Jerry Lundegaard (William H. Macy), who has engineered a plot to have his wife kidnapped by hired thugs (Steve Buscemi and Peter Stormare) in order to the extort a heavy ransom from his wife's tight-walleted father. Lundegaard schemes to use the funds to dissolve the financial avalanche that is threatening to bury him, but his flawlessly planned crime goes awry when his hired abductors gun down a state trooper and two hapless bystanders while transporting Lundegaard's wife to a remote cabin.

After his experience with the Coens on the large-scale, stylistic genre-parody The Hudsucker Proxy (see AC April 1994) Deakins submits that a smaller budget and crew was a welcome change. "It was nice doing Fargo with them after Hudsucker," he attests. "Hudsucker was quite a big picture. [The budget wasn't] a huge amount of money by today's standards, but that project had its own momentum. Fargo, on the other hand, was a small picture, but in a certain sense we could be more flexible because of it. Less pressure, a smaller crew and a much more intimate production are advantages in many ways."

"It was fun for all of us," Joel Coen agrees, "and a relief in a way. It was back to working with each other and a small crew in a very controllable environment, which was similar to how we had done Barton Fink. On Hudsucker, Roger had to essentially oversee four different units: the main unit, the second unit, the bluescreen unit, and the miniature stuff."

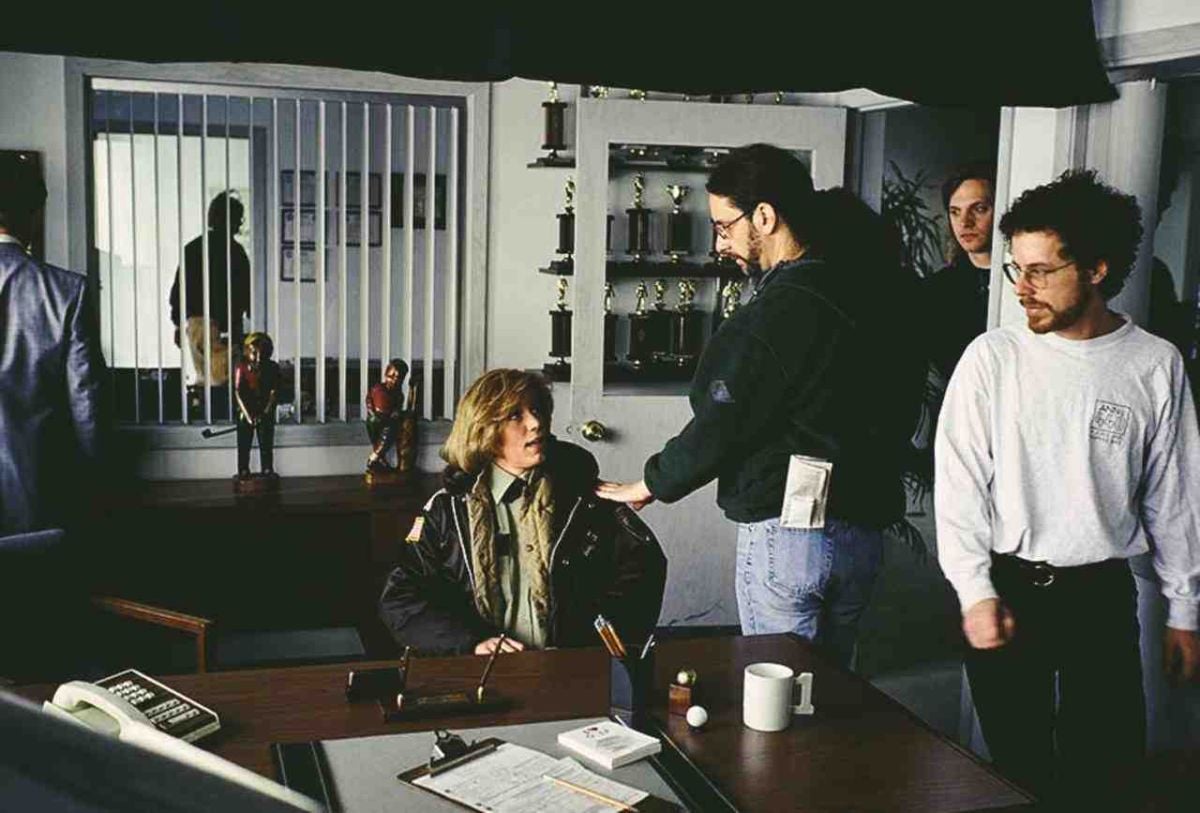

Early on in Fargo's pre-production, the Coens had meetings with Deakins to discuss and solidify the visual style of the film. "We always involve Roger very early," notes Joel. "Basically, what we do after we finish the script is sit down with him and talk in general terms about how we were thinking about it from a visual point of view. Then, in specific terms, we do a draft of the storyboards with Roger — showing him a preliminary draft of what we were thinking about — and then refine those ideas scene by scene. So he's involved pretty much right from the beginning. The style of the shooting is worked out between the three of us."

Even with the detailed preparation, Joel confesses that elements of a scene may depart radically from the storyboarded preconception. He explains, “Frequently, [storyboards] can be tossed out the window when we get on the set and the three of us see something that we'd prefer to do, given the location or whatever. But they're there as a guide, a point of departure for us to start talking about the movie with Roger from a visual point of view."

On set, Deakins and both brothers will work out the dynamics of a given scene, with Joel and Ethan frequently switching hats. "Either of them will be talking about the shot, lenses or whatever," says Deakins. "They just swap around duties. I think having a relationship with them on a couple of films before this made it easier to do a project on a small budget and get more out of it. Once you've got a pattern of working, you know how to cut corners, and what each other's wants are. We don't have as much discussion on the set anymore about shots. We basically block the scene in the morning and go through the shots. It's quite a quiet set!"

"We're very interested in the cinematography," submits Joel. "From the beginning, it's something that we've always spent a lot of time on with Roger because we enjoy it, we enjoy thinking about it, and it's fun for all of us to work out together."

Deakins has had a longstanding debate with the Coens about their affinity for wide-angle lenses, which all too often results in an on-set bidding war for the optimum lens choice. Ethan proclaims, "We've gotten better actually, partly because of Roger's influence." Joel expands wryly, "He has been quietly bringing us around to longer lenses. It's a joke between the three of us. We're now up to 32mm and 35mm lenses!"

Laughing, Deakins retorts, "On Hudsucker I'd put on a 28mm and they'd say, 'Shouldn't this be an 18mm?"' But after three films, Deakins' cajoling seems to have taken root. "On Fargo, we shot longer lenses than the Coens have ever shot before," he notes. "Our main lens was probably a 40mm or a 32mm, whereas normally it would be a 25mm."

"I think it still is a prejudice with us — wanting to go wider more often," admits Ethan. "It has to do with wanting to enhance the camera moves. For instance, in The Hudsucker Proxy, a lot of the effects stuff, the falling shots, were quite wide in the interest of making the moves and the falling more dynamic."

“And that was sort of the idea of this movie," relates Joel. "It was interesting to try and restrain ourselves. Unlike the movies we have done in the past, we wanted to take a more observational approach to this, because the story is partly based on real life. We moved the camera far less and used a lot more over-the-shoulders."

The Coens and Deakins also strove to accentuate the dull and non-eventful nature of the rural Midwest, and to juxtapose this atmosphere against their highly eventful tale. Explains Joel, "First of all, we were trying to reflect the bleak aspect of living in that area in the wintertime — what the light and this sort of landscape does [to a person,] psychologically. It was very important for us to shoot on non-sunny days. We talked early on with Roger about shooting landscapes where you couldn't really see the horizon line — so that the snow-covered ground would be the same color as the sky — on these sort of slight gray or whiteout days that you get in Minnesota.

We scheduled the show so that we would be able to avoid blue skies as much as possible. "In one respect," he continues, "we were unlucky in that there was very little snow in Minnesota while we were shooting there. We actually ended up moving to North Dakota for the end of the show — chasing the snow. On the other hand, the landscape up there is even flatter and more bleak than it is around Minneapolis. We wouldn't have shot there had the weather been alright in Minneapolis, so in a sense we got more interesting exteriors than we might have otherwise."

Deakins concedes, "They wanted [the look of the exteriors] to be quite bland. It's kind of a difficult balance to do something that's bland but not boring. They wanted it very real, very middle-America. In fact, we chose some of the locations because they were particularly bland. Both the designer [Rick Heinrichs] and I would say, 'Well, that's really nothing!' I mean, you still have to make it interesting, but they always manage that anyway. I think the Coens could probably make a blank white wall interesting."

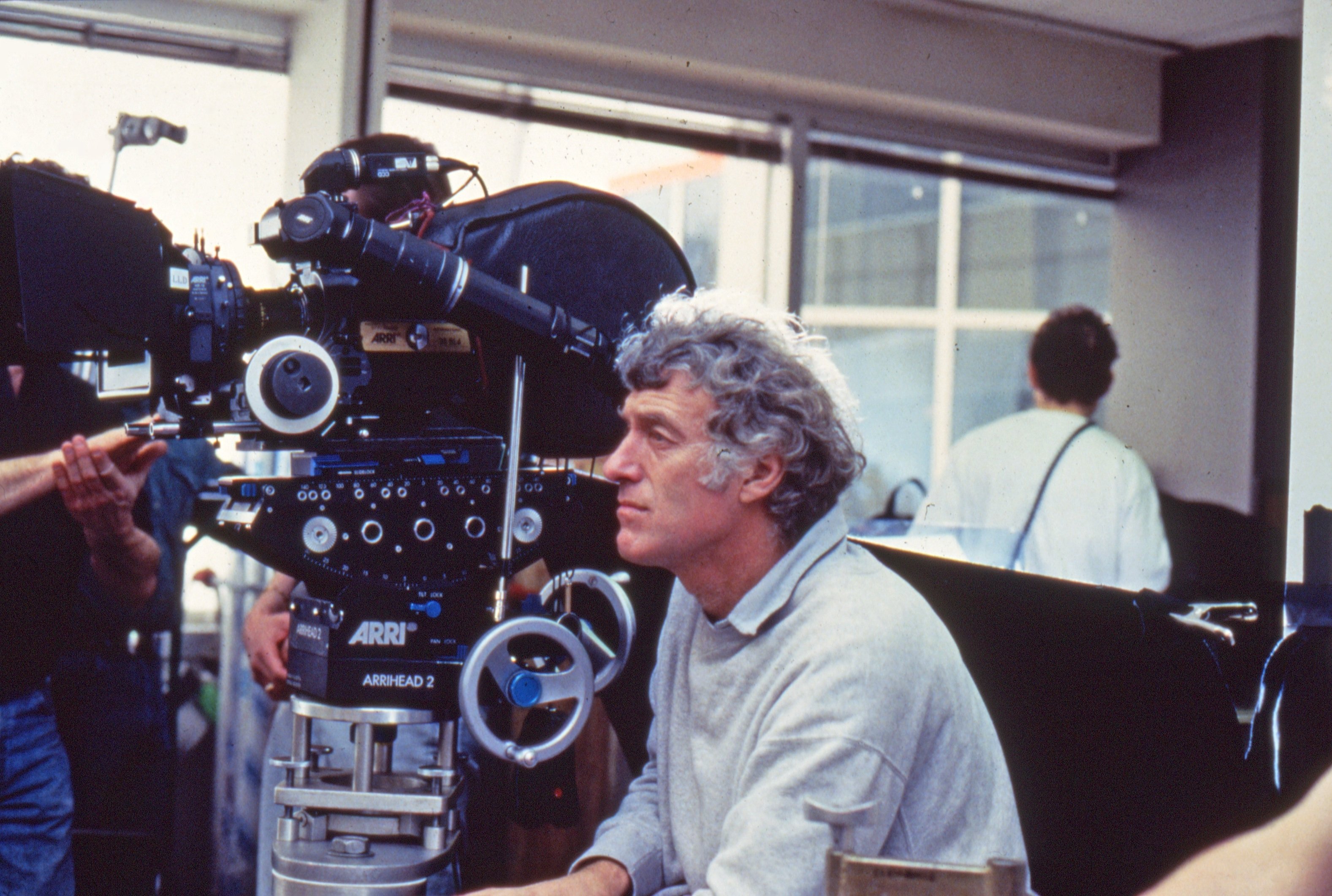

Deakins once again employed his camera of choice, an Arriflex BL-4, outfitted with Zeiss prime lenses. He exposed on his favorite stock, Eastman's 200 ASA EXR 5293. "I've shot on BLs for years. When we were doing car rigs it was probably -10° to start with, plus we were going along at 40 miles per hour. It was pretty cold, but the old BLs handle that pretty well. We also made up heater barneys for the camera and special heated boxes for the batteries so the charge wouldn't drain too quickly."

With its limited budget, all of the film, save for a small bathroom set, was shot on location in Minnesota and North Dakota in practical, working establishments and locales. Utilizing available exterior light through windows and augmenting the existing lighting in a location proved to be a quick and efficient methodology. "I was very much working off of natural sources," recalls Deakins. "It's not something I always do, but I suppose I do it more often than not. Particularly on Fargo, where we wanted a naturalistic feel, I was working a lot more with practicals — boosting practicals and putting little gag lights in. A lot of the film was shot in bars and clubs, so basically you have to work with the production designer to install the kind of practicals you want."

Bill O'Leary, Deakins' gaffer, specifies, "Usually, we go with a high-wattage standard household bulb, like 150 or 200 watts. We then always put the lights on dimmers. Fargo was basically lit with existing fixtures with higher-watt bulbs: we'd go over-wattage, put it all on a dimmer, and then dial it down to warm it up a bit."

"To me, that's the essence of lighting in locations — getting the right practicals," states Deakins. "I'll spend a lot of time with the prop buyer and set dresser just to make sure I've got options with practicals, so that if I want a certain amount of light in a certain place, I can put a practical there rather than have to rig a light. I may also hide a light behind the practical. It gives me flexibility on the set and is much more realistic. Maybe I have a problem thinking that I can't put a light there unless there's a reason for it.

"I didn't really have a big lighting package at all," he remembers, "but I worked within those terms. On something like The Shawshank Redemption, everything was lit. But on Fargo, if there wasn't daylight, we literally couldn't do the shots."

Besides the added intimacy of the smaller crew and a tighter collaboration with Deakins, the Coens also enjoyed being liberated from the logistics of large-scale film production and immense stages. "The last movie we did with Roger was shot entirely on stage, and this movie was entirely real locations with the exception of two small bathroom sets," explains Joel. "Most of the interiors, which were mainly small bedrooms, houses, and offices as opposed to big spaces, were lit by window-light during the day. The impulse here was to de-dramatize things rather than dramatize things. And that extended to the lighting as well."

Says Deakins, "I think it's a dark comedy. You usually light up comedies, but the Coens didn't want to do that. This film was closer to the contrasty style of Barton Fink. Hudsucker, on the other hand, was deliberately less contrasty, deliberately more lush; it wasn't necessarily flat-lit, but it was meant to look kind of opulent. Fargo is meant to look real and raw.

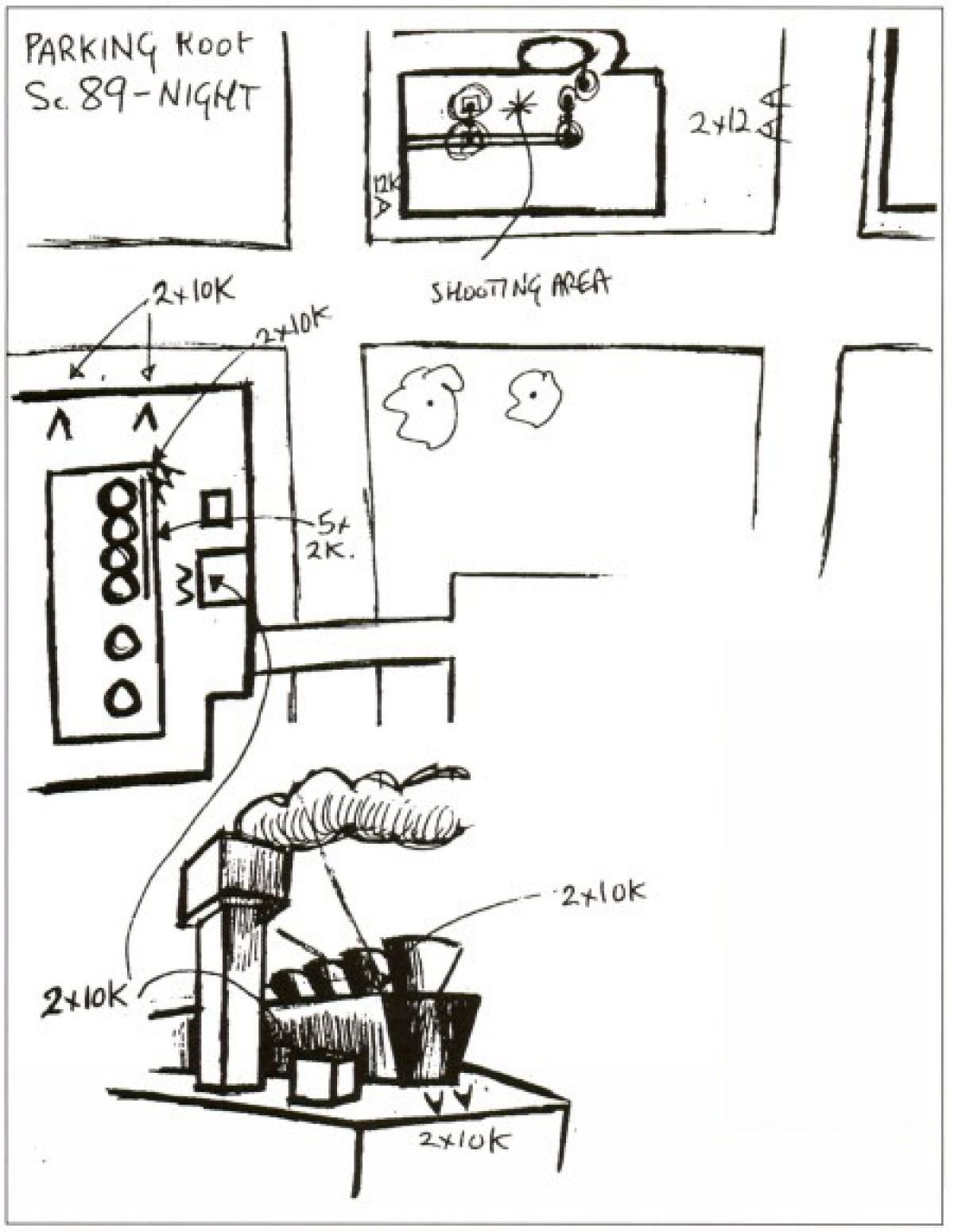

"I religiously do diagrams of every set or location," he continues. "I plan the lighting so that when I get to the set we've had the electricians pre-rigging, and I can look to see if the idea I was going for is working. That also gives me more time to play with the lighting before everybody else is ready to shoot."

For the car chase near the opening of Fargo, the Coens elected to contrast the day snowscape exteriors with a stark-black, sepulchral night sequence. "We wanted the effect of being on the road at night, when everything is totally black," says Deakins. "Then we cut to the daytime, when everything is totally white. There's an incredible contrast. We decided not to do anything like an ambient moonlight effect; we lit the nighttime chase with 12-volt rigs attached to the bumper of the car, as though the shots were lit by washes off the headlights." For the traveling car rigs, O'Leary says that he and best boy Bill Moore utilized "surplus lamps and housings that are used on military-type vehicles and that are actually smaller than a car headlight. Bill, who builds a lot of these rigs, built a bar that we attached to the bumper and set up a row of six of these lights in front of the grill. We could then either pan them further up the road to light into the foreground for shots looking out the windshield, or pan them to the left for angles looking out at the crashed car."

As Lundegaard's scheme to usurp his father-in-law's million-dollar ransom proceeds, the inevitable money-drop is arranged. The simple plan, however, is disrupted when the wealthy and domineering tycoon steps in, demanding to make the drop himself for his daughter's return.

For the pivotal exchange scene, the Coens elected to shoot on top of a snow-covered exterior parking garage. Joel offers, "We chose that location because there was a smokestack belching away on the roof of a nearby building, and we wanted to use that as a background for part of the scene. The special effects people had to snow that entire area because there was no snow. In fact, a lot of the snow in the movie was manufactured."

The scene was lit with harsh yellow-orange sodium-vapor streetlights that spilled warm pools of light on areas around the rooftop. Deakins augmented the look with an orange sodium-vapor effect from above, "which was a combination of 3A CTO and CTS. I think it works quite well because it gives the scene a sort of eerie feeling.

O'Leary adds, "We boosted the streetlamp practicals that were there by building a carriage that sat over the top of the housings like a saddle and hanging a pair of two-light Fay bulbs on either side so that they were running right by the existing sodium-vapor lamps. On each streetlight we had eight extra Fay bulbs to boost the effect. We then just warmed them up a little with CTO and straw to match the warm sodium look

"We lit the surrounding buildings," he continues, "the smokestack tower and the top of a heating plant's cooling stacks, by hiding 10K lamps right on the building's rooftops. We also had 12K FfMIs down on the streets that were corrected halfway back.

Deakins offers, "I worked with a lot more colors on Fargo than I have on either of the Coens' other films. When street lighting started switching from mercury-vapor to sodium, I was a bit worried, because I loved the sort of cold-blue streetlight look. But now I've gotten to like the sodium look.

"I tend to gel lights," he elaborates. "I don't just print things to be a certain color. Some cinematographers print the frame to a particular color, a particular look. I like to use a lot of colors in one frame.

Observes Joel, "I think in a lot of cases Roger was trying to include a warm source and a cold source in the same frame. For example, in a scene in a garage with a mechanic working under a car, there's this warm cage light on him and then cold exterior light coming in.

Outlining his approach to the above-mentioned scene, Deakins notes, "When [actor] William Macy goes to meet the mechanic back in the garage, I shot without a filter. I diffused the windows with 250 and lit them. Because the location was a working car lot, I also changed all of the fluorescent tubes to daylight tubes. I used a practical cage light with a 200-watt bulb on a dimmer that I put under the car the guy was working on. I wanted that light to be really rich and warm, so to get the color difference between the daylight look and the practical, I shot clean uncorrected daylight. Sometimes I like a slightly cold look and I won't correct it on the camera. I'll just pull it back a bit in the lab

"Photographically," he adds, "I wouldn't say that I've been more bold on Fargo, but I did play around a bit more. It's actually one of my favorite projects, though I don't think anything shouts out, 'Wow, this is great photography!' If you've got a huge amount of money and great big sets, it's actually not hard to make it look good. It's often more of a challenge to try to give a film a coherent style from start to finish, one that remains interesting and feels real.

Working with Deakins has rewarded the Coens with a kindred collaborator and a close friend. "We're lucky we found Roger," says Joel. "He understands what we are after, and frequently comes up with stuff on the spot that reflects what we want to do in the scene — but perhaps in a much better realization of it, given the setup.

"However," Ethan cautions, "whenever we fret about some sort of detail in the frame, or starting looking too closely at something, Roger simply says, 'Well, that could be my Gran in the shot and she's been dead for 20 years. Don't worry about it.'

Joel adds wryly, "Actually, there's a lot of discussion about Roger's grandmother on the set. It's an important part of his work and it shouldn't be overlooked."

Deakins was honored with the ASC Lifetime Achievement Award in 2011.