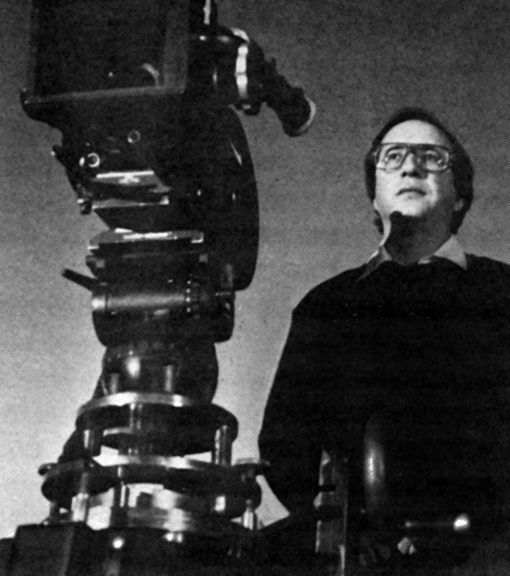

Stephen H. Burum, ASC and Rumble Fish

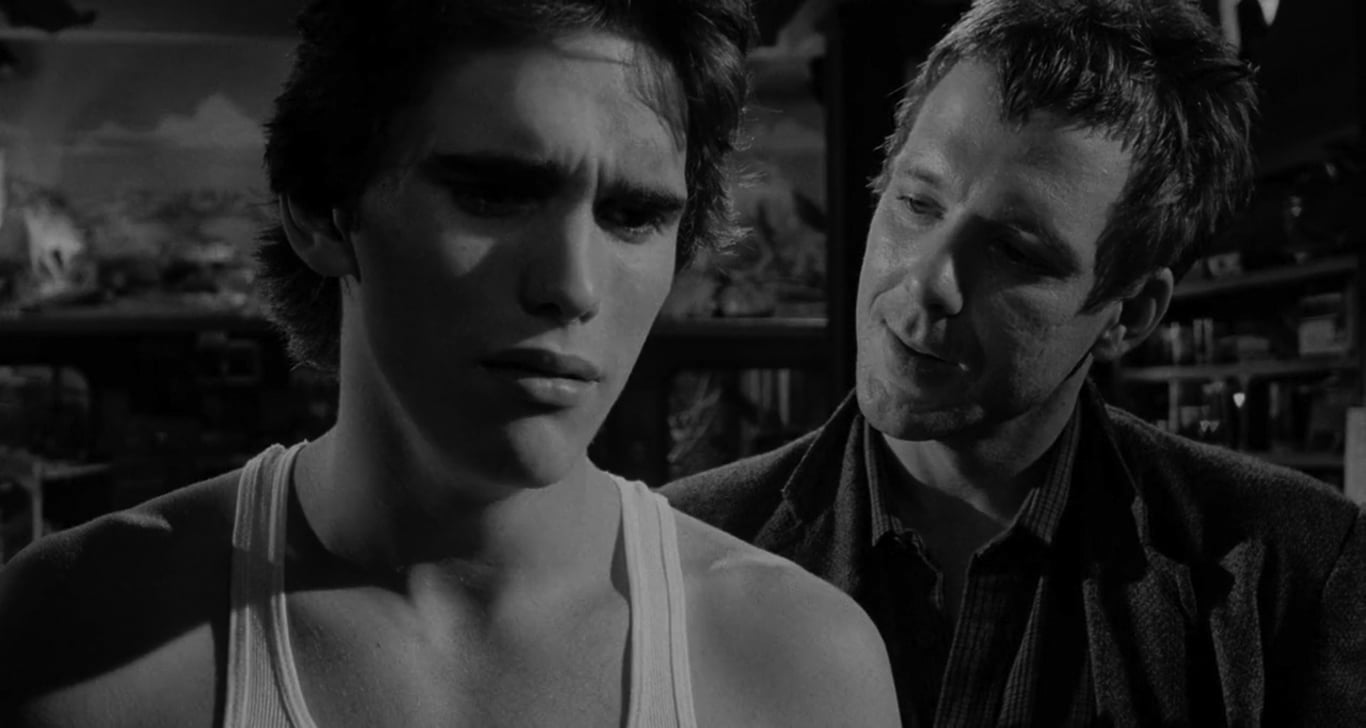

The cinematographer details his visual approach to this stylish and memorable 1983 drama, directed by Francis Coppola.

By Anthony Reveaux

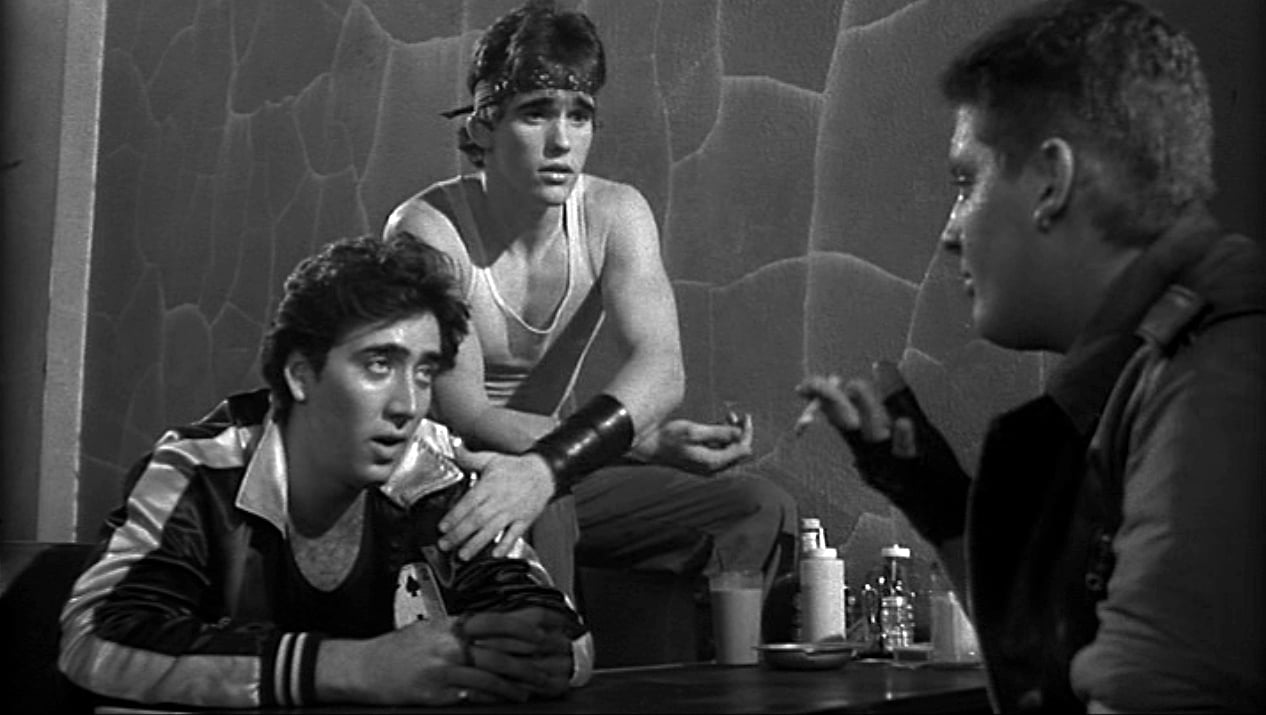

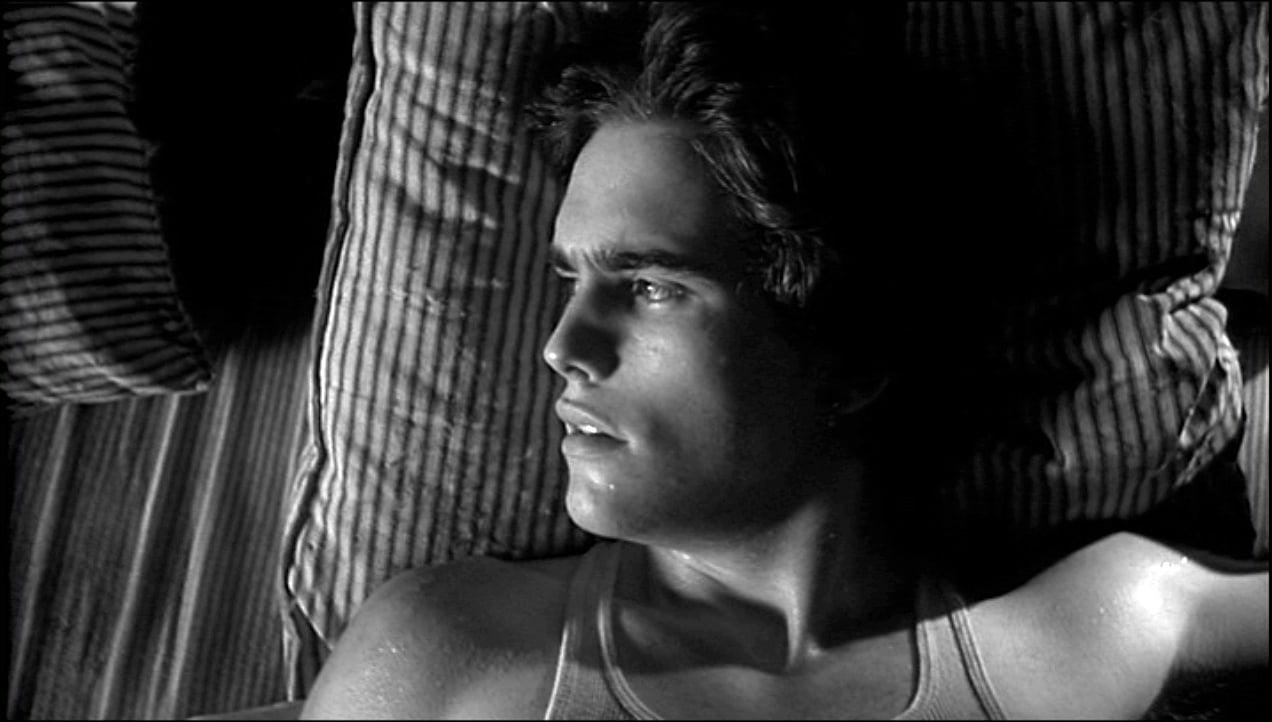

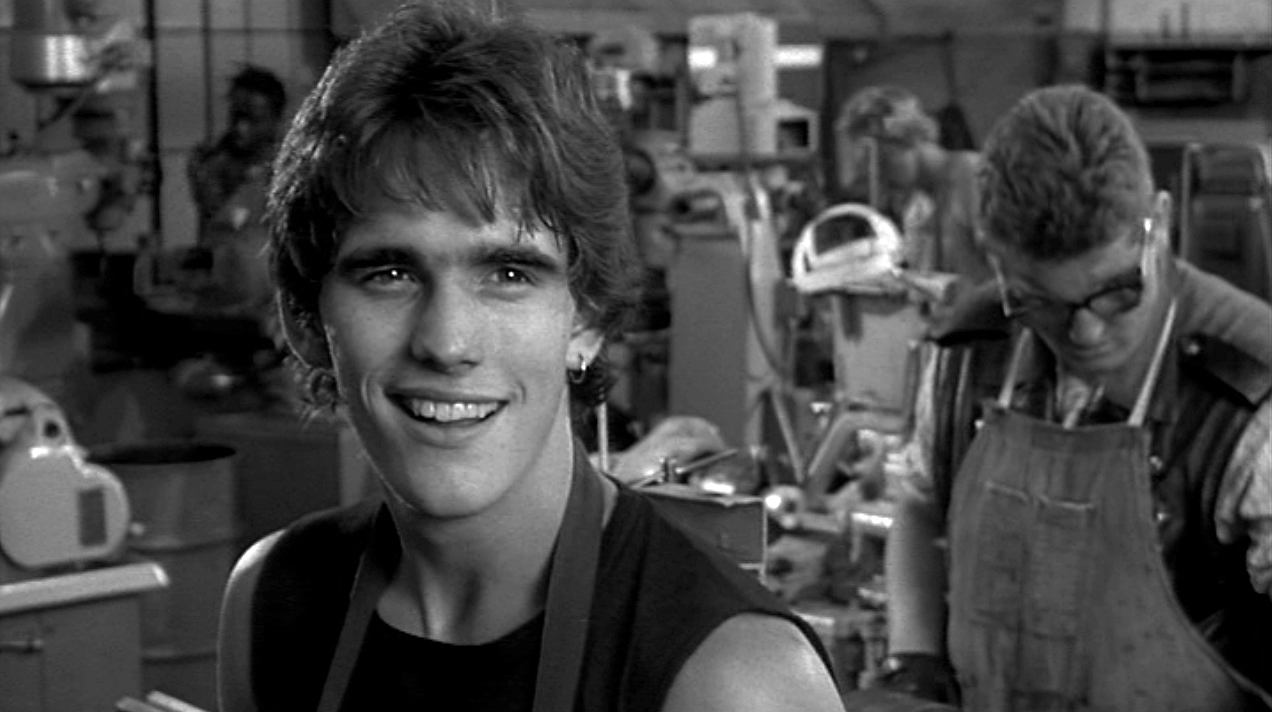

Francis Coppola’s Rumble Fish is a film of directorial risk-taking and stylistic extremes. In a time when black-and-white is still rare in a theatrical release, its cinematography pushes monochrome to a depth and intensity unseen since the German expressionists of two generations past. Compared to even the luminous, lithographic gray scale photographed by Sven Nykvist [ASC] for Ingmar Bergman, Stephen H. Burum ASC’s Rumble Fish is seared on the screen like burnt charcoal and fuming dry ice.

Though Rumble Fish and The Outsiders were both adapted from novels by S.E. Hinton, used some of the same actors and were produced in the same year, the film that is most spiritually akin to it is One From the Heart. His Las Vegas was chromatic confection that cinematographer Vittorio Storaro [ASC, AIC] interpreted in a deeply saturated resonance that comes as close as we can today to the three-strip Technicolor musicals of Donen and Minelli. Another link between the two is Dean Tavoularis, production designer for both pictures. The “look” that Coppola required in One From the Heart was “… not unreal, but not quite real either … a look that was impressionistic and sometimes even surreal.” The reactions to the pictures may be mixed and the returns will not break records, but Coppola’s drive to push film past its limits gives us examples that every director and cameraman can learn much from.

Burum, now shooting Body Double for Brian De Palma, talks about the challenges of Rumble Fish.

American Cinematographer: Did the Rumble Fish company do any pre-production research on other, earlier films for visual style?

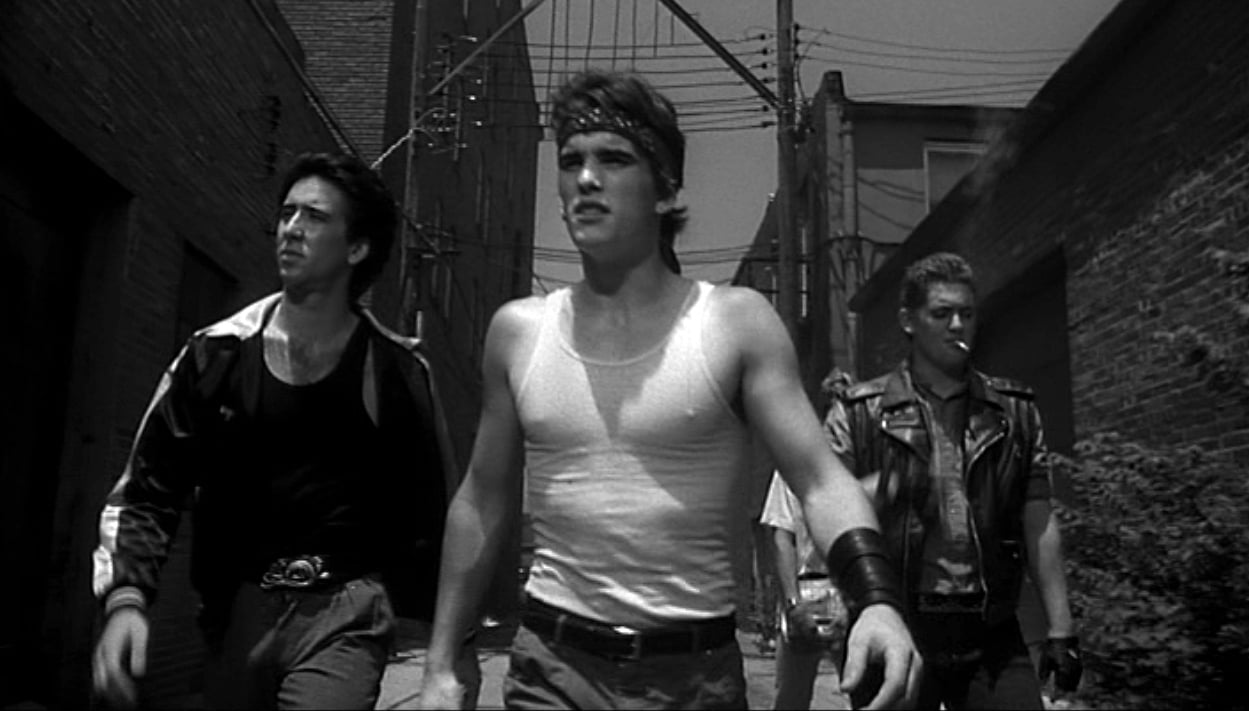

Stephen H. Burum, ASC: For reference points, the first picture that Francis wanted us to look at was the Anatole Litvak film, Decision Before Dawn, which Frank McCarthy produced. Francis knew McCarthy because he had produced Patton, which Francis co-wrote. Decision was a picture about spies in postwar Europe and it was actually shot on location in about 1946. What he wanted Dean Tavolouris to see was its images of ruined cities. That was where all the smoke and obscurity in Rumble Fish came from. He wanted to give the feeling that these kids were operating in a wasteland. It was partial destruction with a leanness in the way things looked. In all, it reflects the mental state of the characters and the chaos in their world.

Another picture that we looked at was Johnny Belinda that Ted McCord [ASC] shot. We did look at some of the German Expressionist films such as The Last Laugh by F.W. Murnau. Francis showed it to the actors, because he wanted more body attitude out of the kids. Emil Jannings’ posture in The Last Laugh becomes more and more forlorn as he is beaten down by life. So Francis way trying to get across to them, especially to Matt Dillon, how important body language was. Even in silent acting you could project that kind of feeling so strongly. We looked at Viva Zapata and Orson Welles’ Macbeth.

Did you look at Kurosawa’s Throne of Blood?

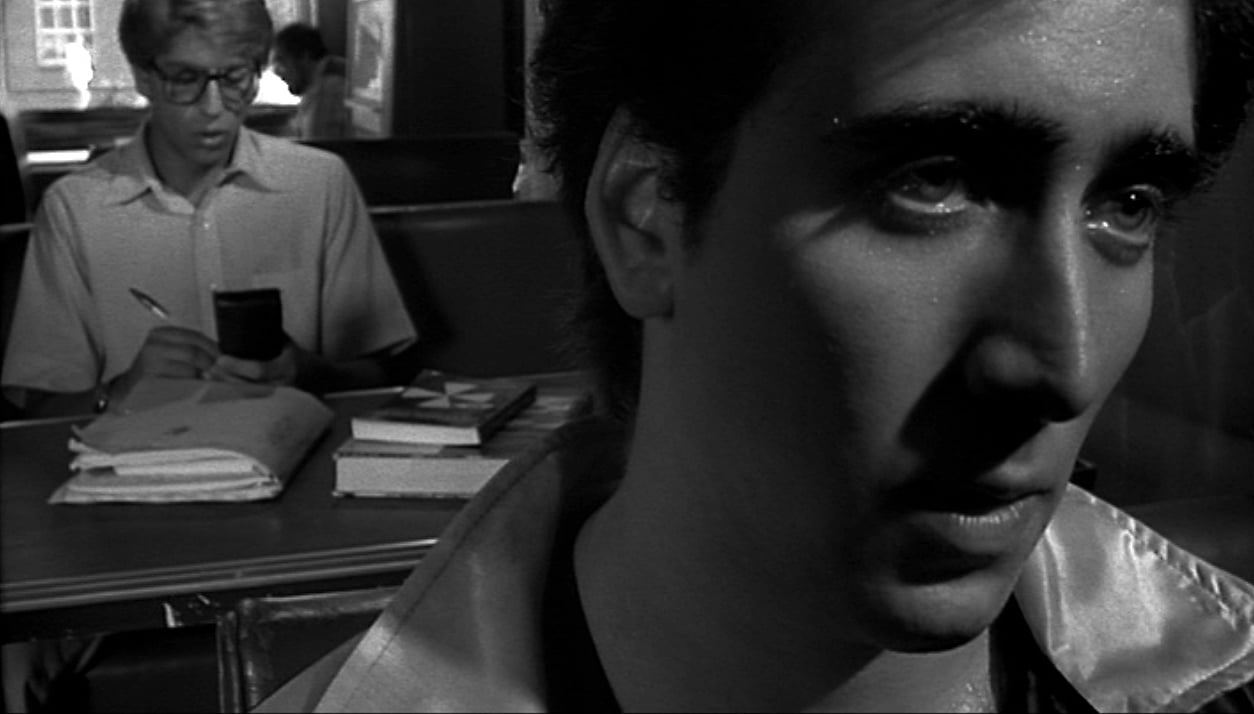

No we didn’t. Kurosawa uses a lot of long lenses and compression. We didn’t want to use a lot of compression. We used the 25mm mostly and we used the 35mm for closeups and the 18mm where we forced perspective. Only once did we use a very long lens. That was the scene where Midge is telling Rusty-James about the conflict between Patterson the Cop and his brother Motorcycle Boy. The smoky atmosphere of the city is flattened behind them. We considered the 25mm our “normal” lens, but also did a lot with the 9.8mm. One shot that looks very “9.8” is where you see the guy in the pool hall talking about time. It was a high, raking shot. In other scenes we masked the 9.8mm shots sufficiently so that you don’t always notice that the perspective is exaggerated.

What black-and-white stock did you use?

We used PX outside and XX inside and XX at night just like they did in the old days.

Was the processing forced?

No, all processing was normal. It was, however, developed to a higher gamma so you have a really good, solid black. To me black is a very important element. Whether you’re shooting color or black-and-white if you don’t have a black reference you don’t have the bottom. Especially when you’re shooting black-and-white you always have to have a black reference in the frame as well as the highlight reference. If you don’t have all that, the gray scale in between just looks like gray mud.

During shooting, were your exposures normal for the stock?

One thing we discovered was that I had to re-do all the filter factors for the black-and-white filters. Somehow something has changed over the years. The old books and the old filter factors no longer work. I did tests with all the filters to get used to doing it again. When I got the tests back everything was all over the place. I had to do a lot of interpolating from what the printer lights were and re-did all the filter factors. Once I did that it all worked fine. So if anybody’s going to shoot a black-and-white picture nowadays I would recommend that they do those tests or else they will find themselves embarrassed the first day!

I wonder what Gordon Willis did for Woody Allen’s shows.

I am very thankful that Gordon Willis [ASC] is doing black-and-white and did his processing with Du Art in New York. Gordon has worked with them so they are really up to snuff. It is only out of his efforts that there’s any black-and-white technology in this county for Woody Allen or anyone else. When we were looking for labs we even tried France and England. But the trouble with the French connection was the customs. Otherwise, it looked pretty good. The English black-and-white was not very good.

I haven’t seen time-lapse sequences, as when the shadows of the fire escape move across the alley, done in any other recent feature.

There was a whole series of time-lapses that were planned. We didn’t have time to do it ourselves, so we brought in someone to take care of it. Out of it all, we only used a couple in the finished film. What you saw was all done on location with an intervalometer.

How was the dream flying sequence with Rusty-James done?

Matt Dillon wore a body mold, which was moved by an articulated arm and also flown with wires.

And the effect where he seems to rise up out of his body?

That was done in the camera. We had one of those 50/50 front-surface mirrors and we used a dimmer that brought up the one image as we took the other out.

One of your most widespread techniques was that we painted shadows on the walls. The pool hall scene, for instance, was filled with them, all painted in there. Not real shadows. There’s a long shot down where you see a window shadow on both sides of the wall. Physically that’s impossible. What we wanted to do was to simulate the sun coming in and its thick heat, but we wanted people to feel that there was something wrong, give them that certain feeling of uneasiness, that something is a little bit off with reality. You just tweak it a little bit. For Patty’s house all the tree branches are painted on the façade.

Then in that respect Rumble Fish does share a common aesthetic with The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari?

No, it’s like the old black-and-white pictures of the 1930s and ’40s. They used to do that a lot. They had small sets and light colored walls, so it was difficult to light and control everything. For instance, where you have two walls coming together they fogged down the corner so you have a strong sense of the corner. Because you had to light straight into it to make the stars look their best, you would lose the feeling of the corner. They would also fog down the tops of the walls so they would feather off into darkness. Those crews were great about doing things like painting the shadows of venetian blinds on the walls if needed. It much was cheaper to do that than have someone outside with an arc. You could therefore just light the whole thing flat, put in the black lighting and retain that wonderful texture and it was all painted in. We really used that ol’ black-and-white tool kit.

What about the lightning effect in the fight scene?

It was used to hype up the action. The distant thunder of discontent. It is really the main combat scene in the picture. This is what Rusty-James idealizes. We dramatized it as glorious and scary and heroic as we could. Pigeons flying through the frame, the train going through, the smoke, the terror. Everything. Your nerves are right on edge and something terrible happens to you. Time stands still for a minute and then you see everything move faster. The lighting is part of that emotional energy. All of that is a way to communicate that there is something tremendous happening.

What was the motivation for that exterior shot with the huge clock on the flatbed truck being so prominent in the foreground?

That’s just an interesting way of presenting the concept of time. We wanted to wrap things a little bit, so we used a super-wide-angle lens. It worked well, giving us a good, strong image that said “time.” You saw a closeup of a prop but also a long shot of the environment and the people in it. There’s also the theme of time going faster and faster, and running out. That’s an idea that has fascinated Francis and you see it deeply in the last two pictures.

We did Rumble Fish back-to-back with The Outsiders and with some of the same talent. The style of The Outsiders was very romantic and passionate because kids think that way. The compositions were classical and pictorial with the camera removed and stoic. Rumble Fish was exactly the opposite; we wanted to shove the camera into the faces of the characters and become more of the psychological storyteller. It gave a certain tone to the continuity. Rumble Fish was far more abstract than The Outsiders.

When the kids are on the street getting drunker and drunker we start doing all this hand-held camera work. It becomes increasingly violent up to the point where Motorcycle Boy leaves the pool hall. Then the kids rush outside to see him. Instead of continuing with all the violence we introduced a sense of visual smoothness when they emerged… like you do when you’re drunk and think you are sober. As they entered the alley we brought the crane shot up high. Then we re-introduced the violence again with camera shake. When we cut down to the hood waiting for them at the gate we held it clear and very static. We tried to do that kind of thing with camera moves and positions throughout the entire picture. The composition and lighting take on the psychological aura of what’s happening in the scene. The Outsiders is not at all like this picture.

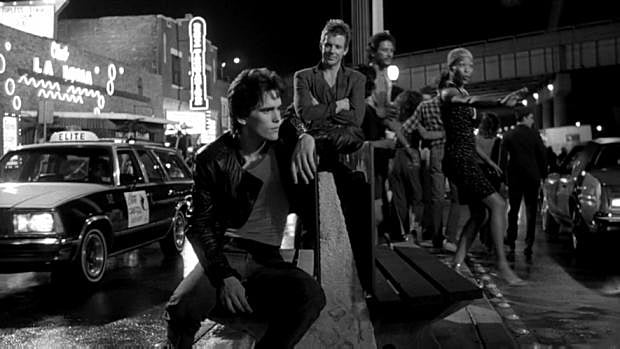

Some people felt that it was too bad that the strip street scene wasn’t in color.

You “know” and “feel” that it’s all in color. The neon signs give you a light source element in an area of darkness that has no character on its own. Makes you imagine that beyond the tattoo parlors and bars there is a whole world that you’ve never seen before.

How were the scenes done that had composite black-and-white and color, like the pet shop interior with the brothers looking at the colored fish?

We went through all the planning permutations you could think of. After going around and around with all kinds of incredibly complicated ideas, we ended up shooting the brothers taking in black-and-white and then projected that footage on a rear projection screen. We put the fish tank in front of it, dropped in the tropical fish and shot it all with color film. Ultimately, it was the simplest thing to do.

Does that mean that the release prints have those color stock sequences spliced in? As they did in the early black-and-white musicals with their color finalés?

That’s correct. And we had a hard time matching them up. The colors of those Siamese fighting fish really look like that; very vivid. The color in the picture is a key to letting you know that the Motorcycle Boy is getting near the edge. It’s the first time that Rusty-James really gets worried when he sees this and the color in the shot signals that as well. The same thing happens to him when his brother is killed by Patterson. You have the flashing red lights, you have this color transition and it’s in and it’s out.

So the color appears in just those two instances?

Yes. It’s in very small sections of the picture. It’s used as a visual pen stoke to communicate an emotional feeling.

You are saying that the color is showing that they are losing control whereas most people would think that the color would represent reality.

Yes, but remember the dialogue and what Motorcycle Boy says. To him, normality means that everything is in black-and-white. He could remember that he saw color at one time, but after their mother left them all he could see then was black-and-white. So when you go back to color you know it is another emotional schism. When that happens to Rusty-James you realize that it’s an emotional schism for him as well. Here is somebody at the brink. Instead of having the actor foam at the mouth and rend his clothes, the color symbolism hopefully puts that across. This whole thing is an experiment. There are three aspects to this picture. There’s a little bit of expressionism in it, a little bit of surrealism and some hyper-realism in it. The best of it and the worst of it all mixed together.

What effect has the video system that Francis developed for One From the Heart had on the production of Rumble Fish?

It has made it easier for me to communicate with the camera operator because I can be a lot more specific. I can correct him in the middle of a shot. Normally I never would have seen it until it was too late. It helps me have a lot more control. It helps Francis and I communicate better when we can both see what is happening at the same time. Both of us have a little picture we can point to. We can make a change and both look it over instead of having to frame the shot and step off the dolly for the other person to see it. Video has been a terrific help and a good thing to have.

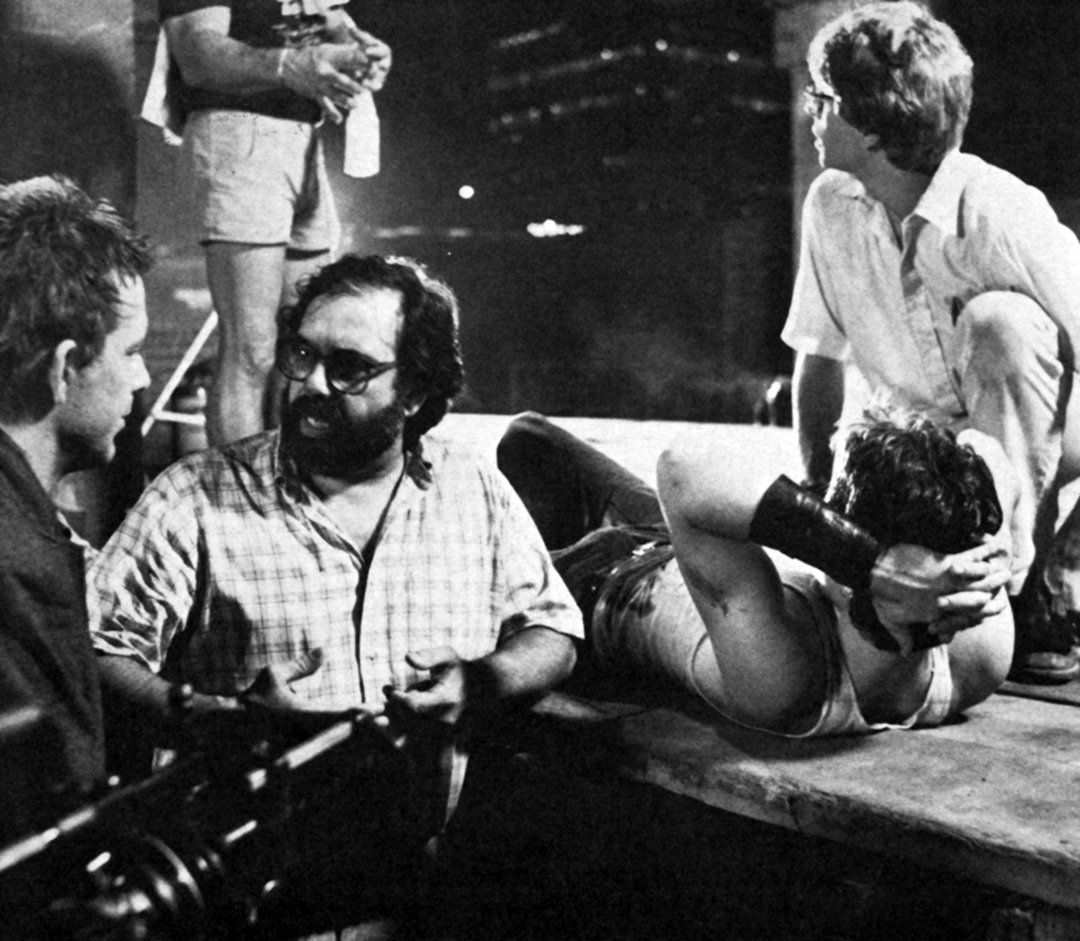

What is Francis’ working relationship with his directors of photography?

What Francis does, and I’m sure he did with Vittorio, is to go to the wall. So both of us went to the wall the best we could. He’s very supportive, always good at cheering you on. Francis is the kind of person who lets you go as far as you can go and if you get in trouble he will drag you back from the brink, but never puts any restrictions on you. He does a kind of creative pyramiding that is very exciting to be a part of. He’s very good at drawing the very best out of everybody he works with. Being a great verbal communicator is also one of his strengths.

Burum’s subsequent credits include St. Elmo’s Fire, The Untouchables (story here), The War of the Roses, Carlito’s Way, Mission: Impossible (story here), Snake Eyes and Mission to Mars.

He was honored with the ASC Lifetime Achievement Award in 2008 and is a frequent instructor in the ASC Master Class Program.

If you enjoy archival and retrospective articles on classic and influential films, you'll find more AC historical coverage here.